Effortful control is the regulatory component of temperament (Kochanska et al., 2000; Rothbart, 1989), involving the voluntary control of attention, behaviour and emotion (Eisenberg, Valiente, & Eggum, 2010; Rueda, 2012). This key aspect of self-regulation appears to be relevant to children’s adjustment and development (e.g., Eisenberg, Spinrad, et al., 2004; Kochanska et al., 2000).

Effortful control includes the capacity to suppress and voluntarily replace a primary response for a secondary one, as well as the capacity to plan and detect errors (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). It encompasses two main types of control: (1) attentional control, which enables the child to voluntarily focus and sustain his/her attention on a specific stimulus, or to switch it to another target when convenient and (2) behavioural control, which can take the form of inhibitory control (the capacity to inhibit a behaviour when necessary) or activational control (the capacity to activate a behaviour in the presence of an urge to avoid it) (Rueda, 2012). Effortful Control differs from automatic and reactive forms of control, which are developed sooner and are potentially less flexible in nature (Derryberry & Rothbart, 1997; Eisenberg, Spinrad, et al., 2004; Rothbart & Derryberry, 2000; Rueda, 2012).

Effortful control starts to develop between six to twelve months of age (Kochanska & Knaack, 2003) and suffers a great progress during the preschool years (Rothbart, 2007) as a result of the rapid development of the executive attention network, appointed as the neural basis of effortful control (Posner & Rothbart, 1998; Rothbart, Derryberry, & Posner, 1994).

Effortful control and adjustment problems

Effortful control is associated with attentional regulation and voluntary modulation of emotions and behaviours, and these processes appear to be relevant to the child’s adjustment (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Eisenberg, Spinard, & Eggum, 2010).

Past research has studied the relationship between effortful control and externalizing and internalizing problems. For example, Kochanska and Knaack (2003) conducted a longitudinal study with 106 children and their parents to explore the associations between effortful control measured at 22, 33 and 45 months of age, using several behavioural tasks, and externalizing problems measured at 73 months of age through parent reports. The results showed that children with higher levels of effortful control revealed decreased levels of externalizing problems at 73 months of age. Consistently, Olson et al. (2005) found a negative association between the dimension of effortful control, assessed by observational measures and parental report, and externalizing problems evaluated by mothers, fathers and educators, in 3-year-old children. Other studies have also described similar cross-sectional as well as longitudinal relationships between those dimensions, using self and hetero-report and/or laboratory observations (e.g., Delgado et al., 2018; Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2000, 2005, 2009; Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Lengua, 2006; Muris et al., 2008; Murray & Kochanska, 2002; Smith & Day, 2018). These negative relationships were found in several age groups, from toddlerhood to adolescence and other cultures (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2007).

Several mechanisms may explain these relationships. On the one hand, externalizing problems tend to be related with deficits in attentional control (e.g., Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Reuben et al., 2016), which may be relevant for maintaining the focus of attention or changing it to neutral stimuli when children are faced with strong impulses and negative emotions (e.g., Eisenberg, Valiente, & Eggum, 2010). On the other hand, those problems are linked to difficulties in inhibitory control (e.g., Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2009; Reuben et al., 2016), relevant for the inhibition of extreme behavioural expressions.

The findings concerning the relationship between effortful control and internalizing problems are particularly inconclusive (Eisenberg et al., 2005; Eisenberg, Smith, et al., 2004). Murray and Kochanska (2002), using behavioural observations and maternal reports, found a positive, but modest, relationship between high levels of effortful control and internalizing problems in a community sample of preschool children. These results are somewhat surprising and may be in part explained by how effortful control was operationalized, with the inclusion of aspects of reactive control and not merely the voluntary control characteristic of effortful control (Einserberg et al., 2005).

On the other hand, other empirical studies have found that high levels of effortful control predict low levels of internalizing problems during the preschool and school years (Delgado et al., 2018; Dennis et al., 2007; Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Lengua, 2006; Muris et al., 2008; Niditch & Varela, 2018), although the strength of this relationship is weaker than the one found for externalizing problems (Delgado et al., 2018; Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Rothbart, 2007), and perhaps even weaker or non-existent for older children (Dennis et al., 2007; Eisenberg et al., 2005).

A key aspect of effortful control - attentional control - may play an important role in the prevention of internalizing problems (see Derryberry & Reed, 2002; Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Muris et al., 2008). Attentional control may help shift the attentional focus from negative thoughts or threatening stimuli to neutral or positive thoughts or stimuli, regulating the inner experience of negative emotions and thus preventing the development of symptoms of anxiety and depression (Eisenberg, Smith, et al., 2004; Eisenberg, Spinard, & Eggum, 2010). The relationship between effortful control and internalizing problems can also be explained by the influence of activational control, which may facilitate the child’s coping with threatening stimuli, even in the presence of anxiety symptoms (Eisenberg, Smith, et al., 2004), reducing the avoidance behaviours characteristic of these problems. The relationship between inhibitory control and internalizing problems remains unclear (e.g., Eisenberg, 2007, see Eisenberg, Spinard, & Eggum, 2010, for a more detailed review; Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg, Valiente, & Eggum, 2010).

Effortful control also plays an important role in the social competence of children, more specifically in the internalization of prosocial behaviours and modulation of the emotional reactions of the child (e.g., Kochanska et al., 2000). An example is the expression of positive emotions when receiving unwanted gifts. Kieras et al.’s (2005) study found in a sample of 62 preschool children that children with high levels of effortful control showed similar positive reactions when receiving both a desired and an unwanted present, while children with lower levels of effortful control showed fewer positive reactions when receiving unwanted gifts than when receiving desired gifts. Other empirical studies have also found associations between effortful control, or its components, and higher levels of prosocial behaviour and social competence (e.g., Dennis et al., 2007; Eisenberg et al., 1996; Eisenberg, Pidada, & Liew, 2001), theory of mind (Carlson & Moses, 2001) and empathy (Rothbart, 2007; Rothbart et al., 1994).

This study

The main objective of this study is to analyze the relationship between effortful control, evaluated through behavioural tasks and parents’ report, and preschool children’s adjustment reported by parents (externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and prosocial behaviour). There is a propensity in previous research towards the exclusive use of parental report in the evaluation of children’s temperament (Majdandžić & Van Den Boom, 2007). For example, a review conducted by Klein and Linhares (2010) of 50 empirical studies corroborates this fact, showing a greater use of questionnaires (88% of the studies). According to the authors, only 13 studies used laboratory or naturalistic observations, of which only 14% used a combined methodology, including the use of questionnaires. Therefore, the combination of behavioural tasks and parents’ report to evaluate effortful control is a strength of this study.

Another relevant contribution of the current study is the independent evaluation of different components of effortful control - attentional and inhibitory control - measured by behavioural tasks. This aspect will allow to examine how these different components are related with parents’ report of internalizing and externalizing problems and prosocial behaviour, enlighting further the mechanisms responsible for these associations. In the light of previous theory and research, we expect externalizing problems to be negatively related to both inhibitory and attentional control. It is also expected that internalizing problems will mostly exhibit a negative relationship with attentional control. Finally, we expect a positive correlation between effortful control and prosocial behaviour which we anticipate might be explained by both components of effortful control.

Method

Participants

Thirty-one Portuguese children aged between 3 and 6 years-old (M=4.06 and SD=1.06) and their parents participated in the present study. Of these, 17 were male (54.8%). All children attended preschool in four schools/institutions, both public and private, located in Lisbon and in its periphery. Most children lived with both parents (83.9%) and had no siblings (80.6%). The majority of the sample belonged to a high socioeconomic level (64.5%) and medium socioeconomic level (29%), with a minority pertaining to a low socioeconomic level (3.2%).

The mothers of the children were aged between 23 and 40 years-old (M=33.68 and SD=4.75), and 71% completed higher education. The fathers were aged between 24 and 49 years-old (M=36.97 and SD=5.54), with 41.9% having completed higher education. Of the thirty-one parents who completed the hetero-report questionnaires used in the present investigation, 29 were female (93.5%).

Measures

Sociodemographic Questionnaire. The sociodemographic data of the child was collected through a questionnaire answered by the parents. Information referring to the age of the child, birth date, number of siblings, birth order, household composition, cohabitation, parents’ marital status, parents’ age, parents’ level of education and socioeconomic status was collected.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire - Portuguese version (SDQ-Por) (Goodman, 1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire is a brief questionnaire that assesses the adjustment of children and adolescents, from 4 to 16 years of age. In the present study, the parent version of the questionnaire was utilized. A division of the questionnaire into three-subscales was used, specifically: (1) Externalizing Problems (conduct + hyperactivity symptoms scales, 10 items); (2) Internalizing Problems (emotional symptoms + peer relationship problems scales, 10 items); (3) Prosocial Behaviour (5 items). The questionnaire also presents a Total Score of Difficulties (20 items), resulting from the sum of the results of all problem subscales. The Portuguese version (Fleitlich et al., 2005) used in the current study presented a satisfactory Cronbach alfa for the Externalizing Problems scale (α=.75) and for the Total Score of Difficulties (α=.71). The dimension of Prosocial Behaviour also presented a satisfactory internal consistency (α=.76), when excluded the items 4 and 17. Finally, the Internalizing Problems scale revealed a lower internal consistency (α=.62), similar to what was found for other studies (see Kersten et al., 2016).

Children’s Behavior Questionnaire - Very Short Form (CBQ - VSF) (Putnam & Rothbart, 2006). The very short form of the Child Behavior Questionnaire assesses the temperament of children aged between 3 and 7 years-old through parental report. Composed by 36 items (12 items per dimension), this CBQ version measures the dimensions of Extraversion/Surgency, Negative Emotionality and Effortful Control. The Portuguese version of this questionnaire (Barros & Goes, 2014) presented in the current study an adequate internal consistency (.74 for Extraversion/Surgency; .73 for Negative Emotionality; .82 for Effortful Control).

The Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB) - Preschool version (Goldsmith et al., 1999). Two tasks of the Portuguese version (Marques & Pereira, 2017) of the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB), “Tower of Patience” and “Bead Sorting”, were used in this study.

Tower of Patience. This task is intended to measure inhibitory control. A game situation is created in which the child is motivated to build a tower with the observer using 15 blocks of wood. The task consists of two sets. The observer gradually increases the time that the child awaits to play during the seven intervals that compose the task, with the exception of the fifth interval, in which the observer proceeds immediately with the game without pausing (i.e., 0 seconds - 5 seconds - 10 seconds - 15 seconds - 0 seconds - 20 seconds - 30 seconds). The coding procedures for this task are described in greater detail by Pereira (2018).

Bead Sorting. This activity aims to measure the child’s maintenance of interest and persistence, through a boring task that requires sorting elastics of four different colors. The child proceeds to separate the elastics, present in a box, by sets of colors, using a vertical abacus, with different compartments for seriation. Coding procedures are described in greater detail by Pereira (2018).

A principal components analysis of the data derived from the tasks revealed two main components: Attentional Control/Persistence and Inhibitory Control. The internal consistency analysis of the two components found showed adequate levels for the dimensions of Attentional Control/Persistence (number of items=7; α=.94) and Inhibitory Control (number of items=2; α=.93). The total Lab-TAB value, composed by 9 items, revealed an adequate Cronbach alpha of .89.

The inter-rater agreement between independent observers of eight observations selected randomly presented an ICC mean of .92 for the Inhibitory Control Component, revealing an excellent agreement between observers. As for the Attentional Control/Persistence component, a good interrater agreement was found, presenting an ICC mean of .85, with the majority of Intra-Class Correlation Coefficient values ranging from 1 to .82, with modest values only being recorded for the level of involvement variable of both sets of the Tower of Patience task (.43 and .51, respectively).

Procedure

The current research was conducted in the context of a larger research project that intended to evaluate the effectiveness of a parenting program (ACT - Raising Safe Children Program) in a Portuguese sample.

Various institutions with preschool education were contacted and four of these institutions agreed to participate. All parents of children aged between 3 and 6 years-old who attended preschool education in those institutions were invited to join the Project. The recruitment varied from institution to institution, ranging from letter form to face-to-face presentations. In an envelope with the referred information leaflet, also followed an informed consent form. A voluntary and informed participation was ensured, as well as the right to post-inquiry clarification.

After receiving all the information, parents signed a consent form and responded autonomously to the evaluation protocol. The questionnaires were completed in session 0 of the ACT Program. Of a universe of 903 parents, 94 were enrolled to participate in the study. Of these, 54 parents started the ACT program, 41 (34 female) of whom continued their participation until the end of the program (with a dropout rate of 24%). For the purpose of data analysis, from the initial sample that delivered the consent to participate in the study (41 children), an enrolment rate of 75.6% was observed.

The parents also allowed their children’s participation in observational tasks - Lab-TAB (preschool version). The observers had specific training for the administration of this type of tasks. The administration of the tasks lasted about 30 minutes. All tasks were presented to the children as “games”. The instructions were described at the beginning of the task and repeated after the first set or if the child appeared to not have understood the rules. The tasks were administered with the presence of only the experimenter and the child. The minimization of distracting stimuli was sought, and spaces provided by the institutions were used for the administration of the tasks (classrooms, psychology gabinets, libraries, etc.). The tasks were videotaped, with the consent of the parents, and later coded.

All codings of the observational tasks were performed by an observer. A second observer independently observed/coded eight videos, selected at random and representing 26% of the total sample, to calculate the inter-rater agreement. The independent observers were previously trained in the coding of the tasks. This training was made possible using two recordings, later excluded from the final sample.

Data analysis

The statistical study of the data was carried out with the statistical analysis software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25, for Windows.

We proceeded with the Lab-TAB data grouping/reduction, which also involved the transformation of variables resulting from the coding of the tasks into z values. Those procedures, as well as the Principal Components Analysis of the Lab-TAB data - which culminated on the finding of two main components, Attentional Control/Persistence and Inhibitory Control - are described by Pereira (2018) in greater detail. The description of the sample was made possible through descriptive statistics procedures. Finally, since it was found that the distribution of all variables in the sample did not respect the normality assumptions (i.e., Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), namely after the attempt to transform the data through the SQRT formula, a non-parametric methodology was used, specifically the Spearman Correlation.

Results

Descriptive analysis

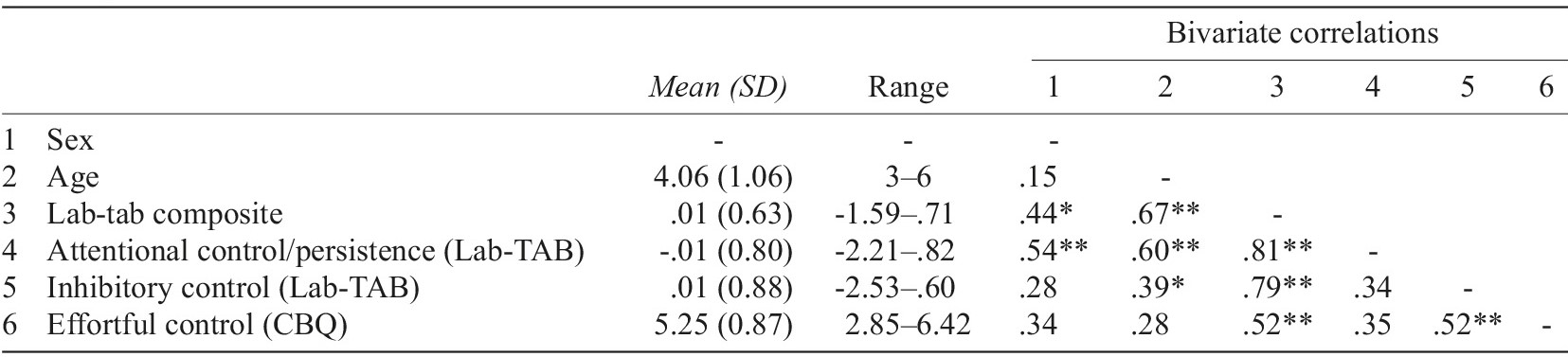

Characterization of the Child’s Temperament. Table 1 shows the central tendency and dispersion measures of the z values of the laboratory observations (Lab-TAB) and of CBQ’s Effortful Control Scale as well as the bivariate correlations between all variables.

Table 1 Lab-TAB’s and CBQ’s central tendency and dispersion measures and bivariate correlations (N=31)

Note. *The correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed); **The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

The results showed a positive significant correlation between Lab-TAB’s Effortful Control Composite and Attentional Control/Persistence and the sex of the child, indicating that girls present a higher level of effortful control than boys. Nevertheless, in relation to Inhibitory Control, the results show a nonsignificant correlation with the sex of the child. Lab-TAB’s Composite and Attentional Control/Persistence showed a strong positive correlation with the age of the child. In turn, Inhibitory Control showed a moderate positive correlation with the latter. CBQ’s Effortful Control didn’t show any statistically significant correlations with the mentioned demographic variables.

Regarding the correlations between the dimensions that make up the construct of Effortful Control, Attentional Control/Persistence and Inhibitory Control, there was a positive association, of a moderate degree, although only marginally significant (r=.34, p=.058). Both these dimensions correlated strongly with Lab-TAB’s Effortful Control Composite. A positive strong correlation was also observed between Effortful Control, when measured through laboratory observations and Effortful Control when measured through parental report. When analysed separately, the dimensions that make up the construct of Effortful Control revealed correlations of different strengths with CBQ’s Effortful Control. Lab TAB’s Inhibitory Control showed a positive and strong correlation with CBQ’s Effortful Control and, in turn, Lab-TAB’s Attentional Control/Persistence did not reveal any significant relationships with the latter.

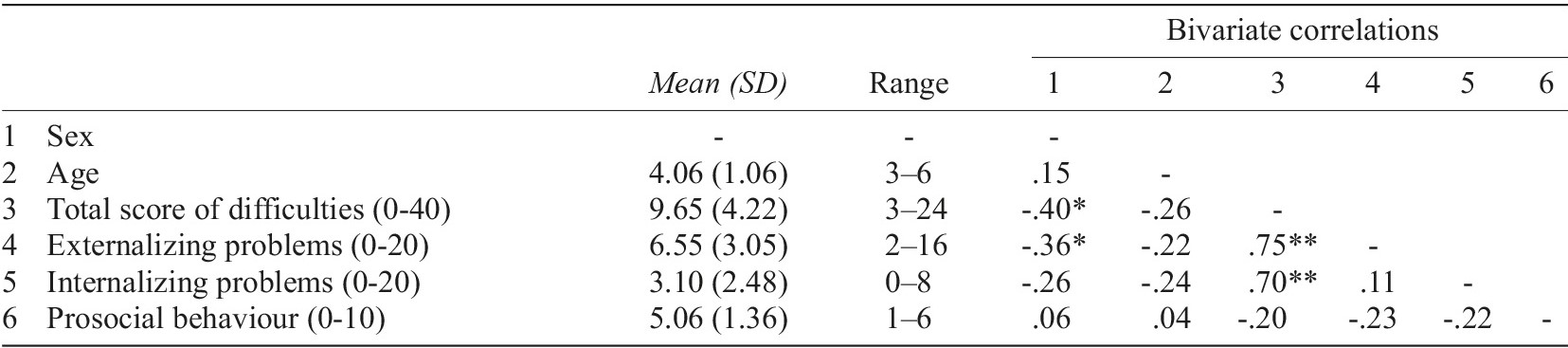

Characterization of the Child’s Adjustment and Prosocial Behaviour.Table 2 reports the measures of central tendency and dispersion obtained through the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) as well as the bivariate correlations between the questionnaire’s scales, age and sex of the child.

Table 2 SDQ’s central tendency and dispersion measures and bivariate correlations (N=31)

Note. *The correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed), **The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

There was a significant moderate relationship between Total Difficulties, as well as Externalizing Problems and the sex of the child. On the other hand, Internalizing Problems and Prosocial Behavior did not reveal any significant correlations with the sex of the child.

Regarding the correlations between the different scales of the SDQ questionnaire, there were significant and strong positive correlations between Total Score of Difficulties and Externalizing Problems and Total Score of Difficulties and Internalizing Problems. There were no significant relationships between Externalizing Problems and Prosocial Behaviour, nor between Internalizing Problems and Prosocial Behaviour or Total Score of Difficulties and Prosocial Behaviour. Similarly, there were no statistically significant relationships between Externalizing and Internalizing Problems.

Correlations between Effortful Control, measured through Lab-TAB and CBQ, and Adjustment Problems (SDQ). We found significant, moderate and negative relationships between Effortful Control measured through laboratory observations and the Total Score of Difficulties scale (r=-.47, p=.008), as well as with the Externalizing Problems scale of the SDQ (r=-.48, p=.006). The relationship between Effortful Control and Internalizing Problems was not significant (r=-.26, p=.152). There were also no significant relationships between the Attentional Control/Persistence (Lab-TAB) component and the dimensions of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, i.e., Total Score of Difficulties (r=-.33, p=.071), Externalizing Problems (r=.33, p=.068), and Internalizing Problems (r=-.23, p=.209). Regarding the Inhibitory Control component, strong and negative relationships were found with Total Score of Difficulties (r=-.52, p=.003) and Externalizing problems (r=-.51; p=.003). No significant relationships were found between the Inhibitory Control component and Internalizing Problems (r=.27; p=.137).

In respect to the relationship between Effortful Control, measured through parental report (CBQ) and Adjustment Problems, moderate negative relationships were found between Effortful Control and Total Score of Difficulties (r=-.47; p=.008). In addition, strong negative correlations were observed between the dimension of Effortful Control and Externalizing problems (r=-.59; p<.001). Statistically significant relationships between Internalizing Problems and Effortful Control were not found (r=-.13; p=.477).

Correlations between Effortful Control and Prosocial Behaviour. There were no significant relationships between Effortful Control, or its components, measured through laboratory observation (Lab-TAB) and the dimensions of Prosocial Behaviour (SDQ). However, there was a moderate positive correlation between Prosocial Behaviour and Effortful Control, measured through parental report (r=.49, p=.005).

Discussion

Effortful control appears to be a crucial dimension for the development of children’s socioemotional competences (e.g., Eisenberg, Smith, et al., 2004; Kochanska et al., 2000). This study sought to explore the relationship between effortful control and adjustment in young children.

Significant negative and moderate associations were found between effortful control, assessed by observational measures and parental report, and global adjustment problems. A moderate negative relationship between effortful control, when measured by laboratory observation, and externalizing problems was also observed. When effortful control was measured through parental report (CBQ) strong negative correlations with externalizing problems were found. These results therefore support conclusions from several previous investigations that suggested that a lower effortful control is associated with an increased risk for the development of externalizing problems (e.g., Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2005, 2009; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Lemery et al., 2002; Lengua, 2006; Murray & Kochanska, 2002; Olson et al., 2005; Reuben et al., 2016; Smith & Day, 2018).

When considering the two effortful control components assessed through laboratory tasks, there were higher associations between externalizing problems and inhibitory control than between externalizing problems and attentional control/persistence. Thus, the children that participated in this study and that present those problems appear to mainly have difficulties in behavioural inhibition and not so much in attentional control. However, given the moderate magnitude of the correlation between attentional control and externalizing problems, this result may be explained by a small sample size which may have prevented statistically significant results.

There were no significant correlations between effortful control, measured through both types of methodology, and internalizing problems. These results are similar to those found in some studies (Dennis et al., 2007; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Eisenberg et al., 2009), but inconsistent with others that suggest a negative relationship between effortful control, particularly at the level of attentional control (Derryberry & Reed, 2002), and internalizing problems in preschool and school-age children (e.g., Delgado et al., 2018; Dennis et al., 2007; Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Lengua, 2006; Niditch & Varela, 2018). Nevertheless, it is commonly reported that the relationships found between internalizing problems and effortful control tend to exhibit a lower magnitude than those found between effortful control and externalizing problems (Delgado et al., 2018; Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Rothbart, 2007). Additionally, in studies where the effects of internalizing problems were controlled for the co-occurrence of externalizing problems, there tends to be a decrease in the magnitude of the relationship between internalizing problems and effortful control (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2005).

A possible explanation for the absence of such associations is that internalizing problems, namely the problems of anxiety and depression, may be more related to difficulties in an activational type of control. In the context of anxiety symptoms, a greater presence of activational control may facilitate the child’s voluntary approach to threatening situations and stimuli, when that is necessary or beneficial (Eisenberg, Smith, et al., 2004), reducing the inhibition or automatic excessive control distinctive of internalizing problems. This aspect was not evaluated by the instruments used in the current study for the measurement of effortful control, the CBQ’s Effortful Control scale and the laboratory tasks applied.

The results found may also be explained by the exclusive use, in the present study, of a parental report to evaluate adjustment problems. In fact, it is known that parents can less easily identify internalizing problems because of their less accessible nature, compared to externalizing problems. Significant relationships between internalizing problems and effortful control may also be better understood when considering its interrelationships with other temperament dimensions (negative emotionality and extraversion) (Nielsen et al., 2019; Van Beveren et al., 2019), which the present study did not explore.

Finally, significant relationships between the child’s prosocial behaviour and effortful control were found, although only when the latter was measured through parental report. The data obtained through parental report suggests that higher levels of effortful control are related to higher levels of prosocial behaviour, similar to what was found by previous studies (Dennis et al., 2007; Eisenberg et al., 1996; Kochanska et al., 2000).

The limitations of the present study are diverse. Firstly, the sample size is small and may have influenced the results referring to the relationship between effortful control and adjustment problems, contributing to the difficulty in detecting significant associations. Secondly, the sample is community-based and mostly composed of children from higher socioeconomic levels. In future studies, these processes should be explored in a more diverse and representative sample. Another limitation of the study is that information about the child’s adjustment and prosocial behaviour was collected through a single informant, mostly the children’s mothers, which may have increased the risk of introducing bias in the collected data. It may be beneficial to maintain efforts to include other reports of the child’s temperament beyond the maternal, such as the paternal or the teacher’s.

The relationship between effortful control and adjustment problems should continue to be explored in future studies. We believe that adjustment problems can be better understood and intervened by understanding the underlying processes, namely those related to temperament, and specifically to effortful control. Particularly, it is important to continue the study of these relationships examining the effects of effortful control’s specific components on adjustment. These relationships may also prove to be distinct in the context of different stages of development, which emphasizes the importance of assessments developed in more than one moment and integrated in a developmental perspective.

In sum, the results of this study, gathered by parental report and observational measures, support the existence of a negative relationship between effortful control and adjustment problems, specifically externalizing problems and total score of difficulties, and a positive relationship between effortful control and prosocial behaviour in a sample of preschool-age Portuguese children. The results do not, however, suggest the existence of significant relationships between effortful control and internalizing problems.