Introduction

Empirical evidence on the construct of presenteeism has continued to evolve since the term was conceptualised to represent a situation whereby ‘people are physically present in the workplace but functionally absent’ (Cooper, 1996) due to ill health. The increased interest in the concept is attributed to its multiple impacts on both the workplace and people (Deery et al., 2014; Gustafsson & Marklund, 2014; Skagen & Collins, 2016). The impacts of presenteeism can be either economic (Robertson & Cooper, 2011) or health-related (Johns, 2011). Previous studies (Aronsson & Gustafsson, 2005; Cooper & Lu, 2016; Johns, 2011) have attempted to arrive at a conceptual compromise on the ‘what’ of people turning up for work despite obvious symptoms of ill health. This preoccupation prompted researchers (Cooper & Lu, 2016; Johns, 2011) to assert that previous studies have succeeded in explaining the ‘what’ but not the ‘why’ of presenteeism. Therefore, further research efforts are required to better understand personal and contextual antecedents of sickness presenteeism.

Generally, scholars (Dudenhöffer et al., 2017; Martinez & Ferreira, 2012; Yıldız et al., 2015) have identified certain variables, like working time and role demands, as factors that relate to sickness presenteeism. These studies have argued that individuals with health issues that could have attracted sick leave may rather consider coming to work when they have less control over their time and much responsibility at work. In a related manner, the health risk factors for presenteeism have also been established in literature (see Martinez & Ferreira, 2012). Furthermore, sickness presenteeism has been found to be positively associated with performance-based self-esteem and over-commitment (Cicei et al., 2013) on the part of employees. Observations in several past studies (Cooper & Lu, 2016; Johns, 2011) showed that further research is needed to understand the dynamics of sickness presenteeism. In line with these observations, the present study investigated the moderating effects of gender in the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism through organisational culture. This was with the aim of providing additional empirical evidence and a theoretical model on the connection among the study variables within the Nigerian context. In addition, findings are useful in adopting an organisational culture that could boost employees’ trust in their employers.

Presenteeism: An emerging construct

Although there were several attempts to conceptualise the construct of presenteeism before the 20th century, the first empirical description of this work behaviour is linked to Simpson (1998) who defined the construct as ‘the tendency to stay at work beyond the time needed for effective performance on the job’. Subsequently, other definitions have emerged describing presenteeism as ‘attending work even when one feels unhealthy’ (Aronsson et al., 2000); and ‘circumstances in which employees come to work even though they are ill, posing potential problems of contagion and lower productivity’ (Work and Family Research Network [WFRN], 2003). Similarly, it is a ‘situation where employees are at work, but their cognitive energy is not devoted to the work’ (Gilbreath & Karimi, 2012). These definitions present two major approaches to discussing presenteeism: health-related (Aronsson et al., 2000; WFRN, 2003) and job-related (Gilbreath & Karimi, 2012; WFRN, 2003). Whatever approach, it portends significant risks for both the organisation and employees. The risk is higher among care and welfare services providers, teachers and instructors (WFRN, 2003), with a higher prevalence among female employees when compared to their male counterparts (Bockerman & Laukkanen, 2010). Presenteeism is an independent risk factor for the future general health of employees (Aysun & Bayram, 2017; Gilbreath & Karimi, 2012). Similarly, it affects organisational productivity and increases health costs (Aysun & Bayram, 2017; Cooper, 2011). Factors that may relate to sickness presenteeism are categorised into health-related, job-related and demographic factors. Health-related factors include stress, depression, flu, pains. Job-related factors include organisational policies, work designs, shift work, long working hours, job insecurity and work replacement polices (Aronsson et al., 2000; Bockerman & Laukkanen, 2010; Cooper, 2011; Webster, 2007). Demographic factors include age, gender, job tenure and job position (Hansen & Anderson, 2008). Thus, the present study investigated the moderating effects of gender on the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism through organisational culture. The choice of gender as a moderator was necessary because of the insinuation that roles performed by a particular gender suffer due to incessant presenteeism.

Perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism

Job insecurity ‘reflects the perception of a threat to the continuity and stability of employment as it is currently experienced’ (Shoss, 2017). That is, the perception that an individual may not be able to keep their job for a period based on evidence from the work environment. This often occurs when the operating environment within a country threatens even the employed few. Nigeria is an example of a country operating under such a threat, where the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) put the unemployment rate at 17.6% in the third quarter of 2018 (National Bureau of Statistics [NBS], 2018).

The effects of job insecurity on various behavioural outcomes are well documented. For instance, one study (Keim et al., 2014) has shown that a low threat to the continued existence of a job minimises the possibility that employees may develop an internal locus of control and role ambiguity. Job insecurity has also been reported to correlate positively with turnover intention (Lee & Jeong, 2017) and emotional exhaustion (Öztürk et al., 2017). Studies that investigated the association between job insecurity and sickness presenteeism are limited. However, it has been established that a significant relationship exists between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism (Jeon et al., 2014). Perceived job insecurity has also been found to be negatively associated with psychological well-being (Huang et al., 2012).

We draw on the social cognitive theory, which stipulates a connection between a person, behaviour and environment (Bandura, 1986). This suggests that an employee’s perception within the context of their work environment is critical to their behavioural outcomes. Thus, when employees perceive that the environmental indices at the workplace threaten their job and feel powerless about the threat, they may attempt to reduce behaviours that could prevent them from losing their jobs, even when they are not feeling well.

Organisational culture and sickness presenteeism

Organisational culture has been defined as ‘shared perceptions of organisational work practices within an organisation’ (Hofstede, 2001; van den Berg & Wilderom, 2004). Organisational culture reflects the way employees and employers view the policies and work practices within a particular organisation. These perceptions are conceived to influence behavioural disposition at various levels of performance. When cultural dictates within an organisation frown at incessant absences due to illness, workers may turn up for work even when they are sick. Studies on organisational culture are diverse and varied. For instance, it has been argued that a relationship exists between job control and presenteeism (Leineweber et al., 2011). It was reported that employees with greater control over their tasks would exhibit less sickness presence compared to those with lower control over their jobs (Leineweber et al., 2011). Also, insufficient supervision has been found to predict sickness presenteeism (Leineweber et al., 2011).

Similarly, presenteeism is inevitable when the organisation’s culture allows a leader to focus more on tasks than on people because employees will make all efforts to be at work to avoid being sanctioned. In a related manner, it has been reported that a lack of supervisor and colleague support predicts sickness presenteeism (Dudenhöffer et al., 2017). Also, when the culture of an organisation denies employees sufficient opportunities to go on breaks or retreat, they may force themselves to come to work ill (Dudenhöffer et al., 2017).

Several models of organisational culture have been proposed; however, Cameron and Quinn’s (2011) competing values framework is most appropriate for this study. The framework has two main dimensions: internal/external and stability/flexibility. The two dimensions yielded four quadrants, namely the clan, adhocracy, hierarchy and market-oriented quadrants.

According to the social cognitive theory of Bandura (1986), human beings have a self-regulated system that permits them to have significant control over what they think about, feel and how they act. It posits that an inseparable interaction exists between an individual, their behaviour and the environment (Bandura, 1986). Therefore, when employees think of the consequences of their sickness absence (particularly in a task-oriented culture), they tend to come to work even when they are supposed to be on sick leave.

Combining these theoretical propositions with little empirical evidence, we propose that organisational culture will mediate the relationship between job insecurity and sickness presenteeism.

Gender, job insecurity, organisational culture and presenteeism

Gender has been conceptualised in literature to reflect the biological sex of either male or female (Adeniji et al., 2015; Fapohunda, 2014; Haigi, 2004). Thus, numerous studies (for example, Paustian-Underdahl et al., 2014; Rutter & Hine, 2005) have been conducted based on this conceptualisation. However, documented studies on gender and sickness presenteeism are sparse. From the studies conducted, we can ascertain that the prevalence of sickness presenteeism was found to be higher among female employees (Martinez & Ferreira, 2012) because women do not want to burden their colleagues with additional responsibilities (Johansen et al., 2014). Similarly, sickness presenteeism was found to be mostly reported among women than men in a hospital sample (Aysun & Bayram, 2017). Most of these studies have focused on the possible relationship between gender and sickness presenteeism, with little attention on testing the moderated mediation effects. Therefore, we proposed that gender will moderate the mediating effects of organisational culture on the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Conceptual Model of the conditional effect of gender in the link between job insecurity and presenteeism through organisational culture

Based on the conceptual model that emerged from the reviews, we hypothesised that:

H1: Perceived job insecurity will predict sickness presenteeism;

H2: Perceived job insecurity will predict organisational culture;

H3: Organisational culture will predict sickness presenteeism;

H4: Organisational culture will mediate the relationship between perceived job insecurity, and sickness presenteeism;

H5: Gender will moderate the mediating effects of organisational culture on the relationship between job insecurity and sickness presenteeism.

Methods

Participants

The cross-sectional research design was adopted to source primary data from employees. These employees were permanent staff of the Local Government Service Commission in Osun state. Participants were selected randomly from the three senatorial districts in the state (Osun Central, East and West districts) to ensure representativeness. Two local government councils were selected from each district. In all, employees from six local government councils participated in the study.

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Local Government Service Commission before embarking on the study. Participants were also informed that their participation in the survey was voluntary and that their responses would be kept confidential. They also appended their signature on the consent form attached to each questionnaire. We administered approximately 300 copies of the questionnaire. Of these, 244 (F=140; M=104) were returned, representing an 81.3% response rate. The returned questionnaires were cleaned and used for data analysis. The distribution of participants by the number of years spent on the job showed that 150 (61.5%) of respondents had worked with the Local Government Commission between 1 and 10 years. A higher proportion (77%) of the respondents were married, while 19.7% and 3.3% were single and widowed, respectively.

Measures

The data collection instruments contained several sections. It is pertinent to state that data on gender were assessed by asking respondents to indicate ‘male’ or ‘female’ in the first section of the research instrument. Similarly, job tenure, a control variable in the study, was accessed by requesting participants to indicate how long they had worked with their organisation.

Presenteeism. Presenteeism was measured with the Stanford Presenteeism Scale-6 (Koopman et al., 2002). The scale has six items that relate to ‘coming to work while ill’ with its attendant performance loss. Sample items include ‘because of my health’ and ‘the stress of my job was much harder to handle.’ The response format is of the Likert type with five response options that range from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’). A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 was reported for the scale by previous authors. Higher scores suggest higher sickness presenteeism and subsequent performance loss. However, to establish the appropriateness of the scale for Nigerian samples, a two-week pilot study was conducted using Local Government employees who were not part of the study from other parts of the state. The pilot yielded a test-retest reliability coefficient of 0.78.

Organisational culture. Organisational culture was measured using the Organisational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) developed by Cameron and Quinn (2011). The study adapted 16 items from the scale’s original 24 items. The excluded items were not represented in the behaviours of public service employees in Nigeria. For instance, items that sought to generate a response on ‘competitive market leadership’, ‘low-cost production’, ‘attainment of target’, and the like were excluded because Local Government employees are principally responsible for service delivery. The response format was a 5-point Likert format ranging from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’). Since the scale was adapted, a validation study was conducted to ascertain the psychometric properties of the new version. The test-retest reliability yielded a coefficient of r of 0.84.

Perceived job insecurity. Job insecurity was assessed using the Job Insecurity Inventory (JII) (Ashford et al., 1989). The inventory is a 13-item scale with two sub-scales, namely, perceived job threat and powerlessness. Sample items include: ‘how do you think losing your job and being laid off permanently may affect you in the future?’ and ‘I have enough power in this organisation to control what might affect my job’. The JII has a 5-point Likert format of responses ranging from 1 (‘very unlikely’) to 2 (‘very likely’). The authors reported reliability estimates of 0.74 and 0.92 (Ashford et al., 1989). The pilot study results yielded a test-retest reliability coefficient of 0.77 and 0.86 for perceived job threat and powerlessness, respectively and 0.88 for the overall JII since the study considered the two sub-scales together in the description of perceived job insecurity.

Data analysis

The authors used the IBM® SPSS® Statistics 23 to analyse the descriptive data and inter- correlation among the variables to ascertain the association among all the study variables. Mediation analysis was conducted after the presentation of zero-order correlation of the major variables. SPSS PROCESS macro developed by Hayes and Preacher (2014) was employed to estimate the conditional indirect effect. The use of Hayes PROCESS macro has gained much popularity among researchers when dealing with the estimation of the mediation model (Cero & Sifers, 2013; Chardon et al., 2016). The SPSS PROCESS macro has been reported to be significantly superior to the traditional Baron and Kenny’s three step approach (Baron & Kenny, 1986), which has various shortcomings (Hayes, 2013; MacKinnon et al., 2002). Hayes PROCESS macro uses a bootstrapping approach to estimate model coefficient with confidence interval. In using the PROCESS macro, data does not need to follow the assumption of normal distribution to estimate reliable parameters.

Results

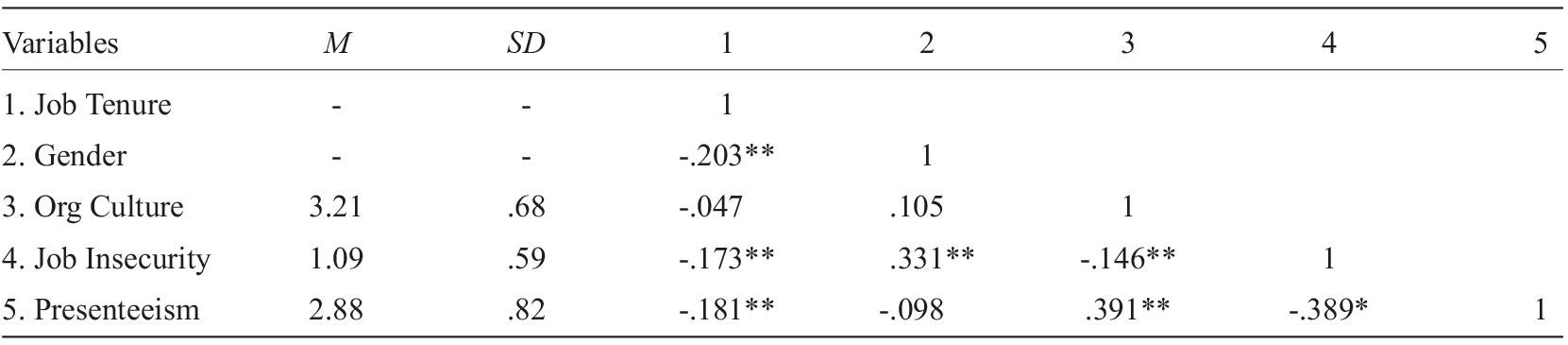

The result of zero-order correlation of the major variables, as presented in Table 1, revealed that perceived job insecurity negatively related to sickness presenteeism (r=−.389, p<.05) and organisational culture (r=-.146, p<.05). Furthermore, job tenure had an inverse relationship with presenteeism (r=-.181, p<.05) and job insecurity (r=-.173, p<.05). At the same time, gender was found to be positively related to perceived job insecurity (r=.331, p<.05).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

Note. Gender (M=1, F=0), Job tenure (1=1-10yrs, 0=11-20yrs), **=significant at 0.05% (two-tailed).

Mediation analysis

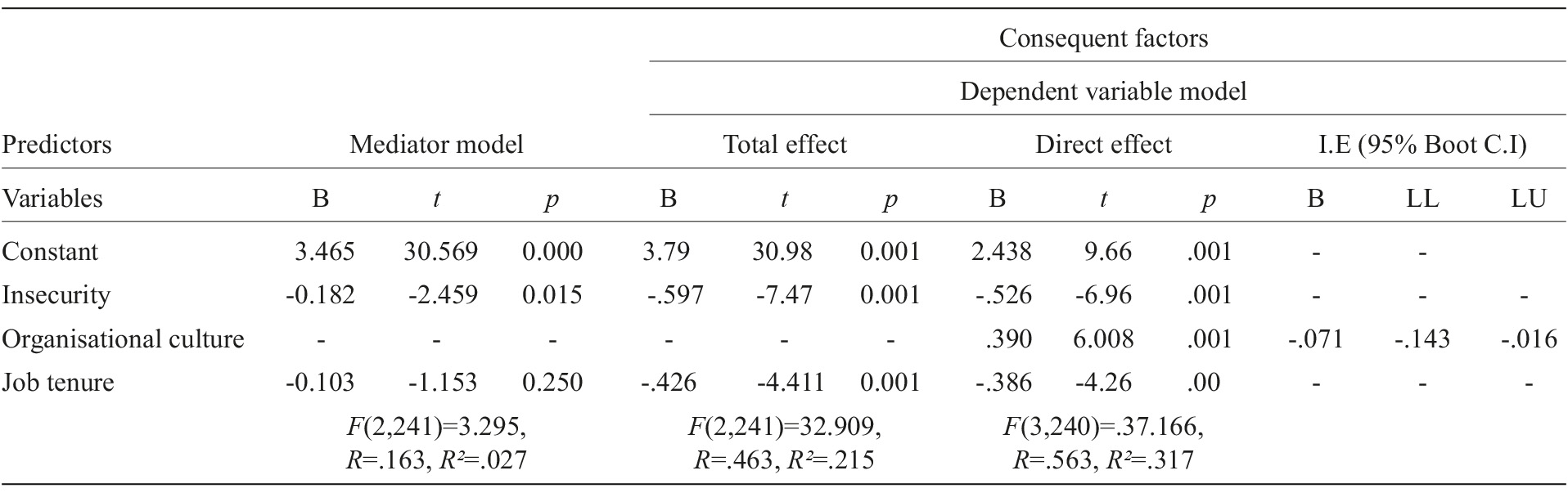

We used Hayes PROCESS macro for SPSS provided by Hayes (2013), for 5000 bootstrap estimates to generate 95% bias‐corrected confidence intervals for the observed indirect effects, the analysis result is presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Simple mediation model of perceived job insecurity, organisational culture and sickness presenteeism

Note. I.E=Indirect effect, C.I=Confidence interval, Boot=Bootstrapping.

It was observed that perceived job insecurity negatively predicted sickness presenteeism among employees (B=-.597, t=-7.47, p<.05). This result supported the first hypothesis, which stated that perceived job insecurity would have significant effects on sickness presenteeism. It was also observed that perceived job insecurity had a significantly negative effect on the perception of organisational culture among employees (B=-.182, t=-2.459, p<.05). This observation supported the proposition of the second hypothesis that job insecurity and organisational culture would be negatively related. Regarding the third hypothesis, it was found that organisational culture had a significant positive effect on sickness presenteeism (B=.390, t=6.008, p<.05). The result supported the proposition of Hypothesis 3. This suggests that organisational culture tends to enhance going to work even if a worker is not in perfect health.

In term of mediation analysis, the results in Table 2 indicate that organisational culture mediated the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism [B=-.071, C.I (-143, -016)]. The results supported the postulation of the fourth hypothesis, which stated that there would be significant indirect effect of organisational culture on the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism among workers. However, the mediation effect was observed to be partial as the independent variable still had an effect on the dependent variable after the inclusion of the mediator into the model.

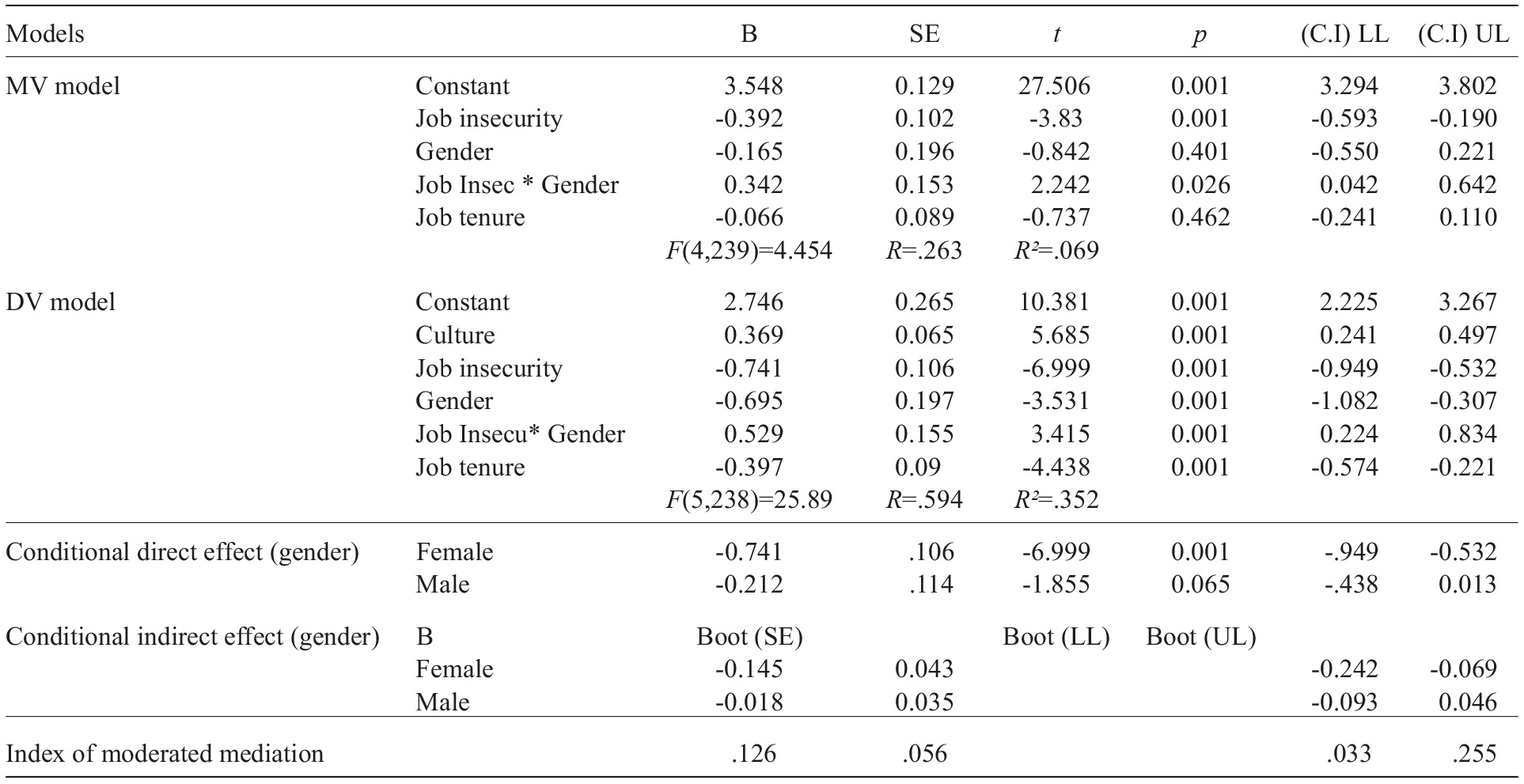

Moderated mediation analysis

Hypothesis 5, stated that gender would moderate the mediating role of organisational culture on the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism among workers. Results supported the mediation hypothesis suggesting that organisational culture was a significant mediator on the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism. The objective of this moderated mediation was to examine the condition under which this mediation effect could hold in term of conditional indirect effect (Hayes & Preacher, 2014). Specifically, Hypothesis 5 aimed at examining whether this mediating role would be applicable to both male and female employees. Again, PROCESS macro, Model 8 was employed to test this conditional indirect effect using 5000 bootstrap estimates to generate 95% bias‐corrected confidence intervals for the observed indirect effects. The analysis result is presented in Table 3.

Table 3 Moderated mediation model of sickness presenteeism among LG workers

Note. I.E=Indirect effect, C.I=Confidence Interval, Boot=Bootstrapping.

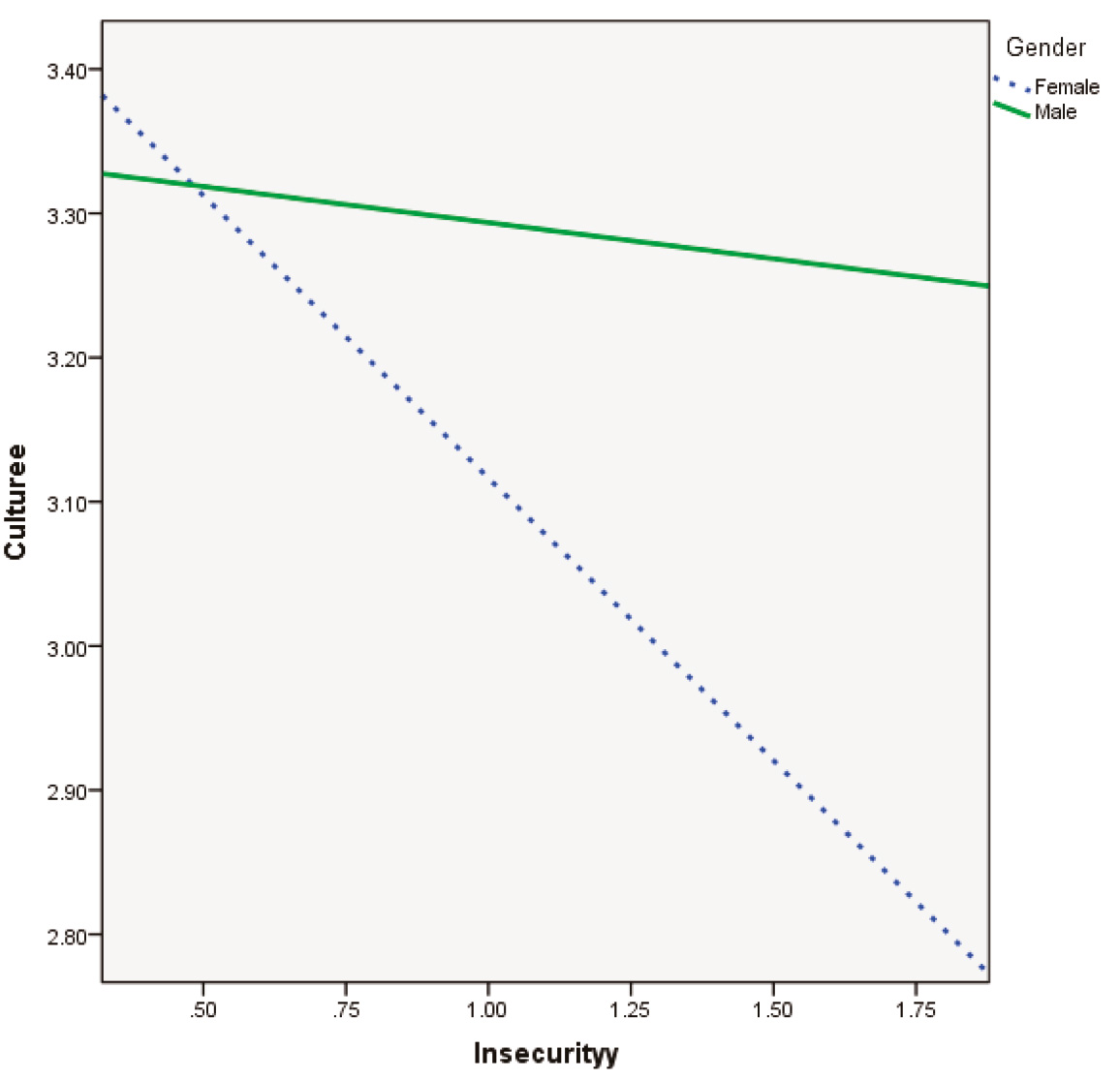

Results in Table 3 show that the conditional indirect effect of perceived job insecurity only holds among female employees [B=-.145, C.I (-.242, -.069)], while this condition was not found to hold among male employees [B=-.093, C.I (-.093, .046)]. This finding suggested that the indirect effect of perceived job insecurity on sickness presenteeism through organisational culture only occurred among female employees and was not found to be significant among male employees (see Figure 2). This finding supported the postulation of the fifth hypothesis.

Discussion

In this present study, we investigated the conditional indirect effects of gender on the predictive roles of perceived job insecurity on sickness presenteeism through organisational culture among employees in Nigeria’s Local Government Commission. To achieve the overall aim, we examined the relationship between the antecedents and outcome variables in the study. Therefore, we proposed a model that would connect the predictor variable to the outcome variable as well as the mediator and moderator between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism.

The study findings confirmed our postulations. Both perceived job insecurity and organisational culture positively predicted sickness presenteeism. It has been established that perceived job insecurity potentially compelled workers to come to work when they are obviously indisposed (Jeon et al., 2014). This implies that employees may likely go to work when they are not functionally fit to do so because they fear losing their jobs. When employees perceive threats to their continued job retention, and they are powerless about the object of the threat, they rather present themselves at work with symptoms of ailments. It was also found that perceived job insecurity negatively predicted organisational culture and that organisational culture predicted sickness presenteeism. This suggests that a task-oriented organisational culture may likely encourage sickness presenteeism. The findings supported the arguments of previous scholars (Dudenhöffer et al., 2017) that sickness presenteeism is inevitable when organisational culture does not permit employees to go for breaks, leave or retreat. Similarly, past researchers (Leineweber et al., 2011) opined that sickness presenteeism may likely increase when the culture of an organisation does not permit sufficient leadership support.

Findings from the third hypothesis, which stated that organisational culture would mediate the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism, were confirmed. In other words, it was found that organisational culture partially mediated the already existing relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism. We also tested for moderated mediation effects of gender on the mediating role of organisational culture on the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism. The findings revealed that the indirect effects of perceived job insecurity on sickness presenteeism through organisational culture only hold among female respondents. The findings of this present study support previous studies that reported sickness presenteeism to be higher among women than men (see Johansen et al., 2014; Martinez & Ferreira, 2012). This may be unrelated to women’s concerns for others (co-workers included). Women, in their nature, may consider the implication of losing their jobs in the event of sickness absence more than their male counterparts.

This study has some limitations. First, we used quantitative analysis; future research may consider a mixed method approach in order to access and report the felt emotions of participants on the subject matter. Second, since the study was conducted among government employees, its generalisability may be limited to such participants. Hence, further studies may consider other sectors in Nigeria like health, education and hospitality. Such studies will provide additional data that could enrich the robustness of our knowledge of the construct of presenteeism within the context of work. Third, comparative studies of the prevalence of presenteeism among various sectors and industries may also be considered.

Conclusion

Most studies on the concept of presenteeism have concentrated on the ‘what’ and not ‘why’ of presenteeism (see Cooper & Lu, 2016). The purpose of this study was to contribute to studies on the ‘why’ of presenteeism by investigating the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism through organisational culture. Our study advanced knowledge on the antecedents of sickness presenteeism in three specific ways. First, it added to scanty existing studies on the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism. It revealed that job insecurity predicted sickness presenteeism. Second, the research established a partial mediation of organisational culture on the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism. Third, we found that gender moderated the mediating effects of organisational culture on the relationship between perceived job insecurity and sickness presenteeism. Specifically, we found that the indirect effects of perceived job insecurity on sickness presenteeism through organisational culture only hold among female employees. This means that female employees will report to work while sick more than their male counterparts in the face of perceived job insecurity mediated by organisational culture. A more flexible culture that permits employees to speedily enjoy sick leave without the prospect of abuse should be encouraged. Accessible healthcare facilities may also be provided at the workplace for the benefit of workers.