Adult psychopathic personality is commonly described as a multidimensional construct that includes at least three dimensions: interpersonal, affective/callous-unemotional (CU), and behavioral/lifestyle (Cooke & Michie, 2001; Hare & Neumann, 2008). The interpersonal dimension typically refers to traits such as lying, manipulation, deceitfulness, dishonesty, grandiosity, and glibness/superficial charm (Cooke & Michie, 2001). The affective/CU dimension refers to a lack of empathy, callousness, shallow affect, failure to accept responsibility for one’s actions, and lack of guilt or remorse (Cooke & Michie, 2001). Lastly, the behavioral/lifestyle dimension refers to impulsivity, need for stimulation, sensation seeking, proneness to boredom, parasitic lifestyle, and lack of realistic long-term goals and responsibility (Barroso et al., 2021; Cooke & Michie, 2001; Pechorro et al., 2016). During the past decades, this psychopathic construct has been extended to childhood and adolescence.

Severe behavioral problems in childhood are highly prevalent (Gatej et al., 2019), and mounting evidence shows that several characteristic traits of adults with psychopathic personalities can be identified in children and adolescents (e.g., Frick et al., 2014; Lynam et al., 2009; Salekin, 2008; Salekin & Lynam, 2010), since psychopathic traits are considered moderately stable over time (Andershed, 2010). Recent attempts have been made to measure the psychopathic personality construct in early childhood (Colins et al., 2014, 2017). Verbally deceiving others (e.g., Lewis et al., 1989), lying strategically (e.g., Fu et al., 2012), and deliberate attempts to mislead (Pollak & Harris, 1999) can be observed as early as the age of three years old. There is evidence that even preschool children can lie when given the opportunity (Hala et al., 1991), and some are chronic liars (Stouthamer-Loeber, 1986), as deficits in emotional functioning can be observed as early as three years old, suggesting that the affective/CU dimension can be measured early in life.

Since psychopathic personality is a developmental disorder with roots in early childhood, understanding psychopathy traits at earlier ages can help clinicians and researchers design and structure ways to intervene in serious behavioral problems by offering preventive interventions or early treatment programs (van Baardewijk et al., 2011). In addition, the combination of affective/CU traits and behavioral problems in youth is associated with adult psychopathy traits, such as sensation seeking, fearlessness, deficient emotional processing, and severe, chronic, and proactive antisocial and violent behavior (Kimonis et al., 2016). This prediction of externalization behavior was also detected in children. Recent research shows that a psychopathy total score at ages 5-7 predicted stable conduct disorder symptoms six years later (Colins et al., 2021). Therefore, understanding the stability of psychopathic traits from childhood to adulthood is crucial to understanding the determinants of criminal behavior (Colins et al., 2014).

The Child Problematic Traits Inventory (CPTI; Colins et al., 2014) is the first tool to assess early childhood traits commonly measured in adolescents and adults. This 28-item tool assesses traits in 3 to 12-year-old children that load on interpersonal (labeled Grandiose-Deceitful, GD), affective (labeled CU), and behavioral/lifestyle (labeled Impulsive-Need for Stimulation, INS) dimensions (Colins et al., 2014). Young people with high scores on the CPTI have more behavioral problems and display more aggressive behavior than those with low scores (Andershed et al., 2008; Colins et al., 2012; Vincent et al., 2003).

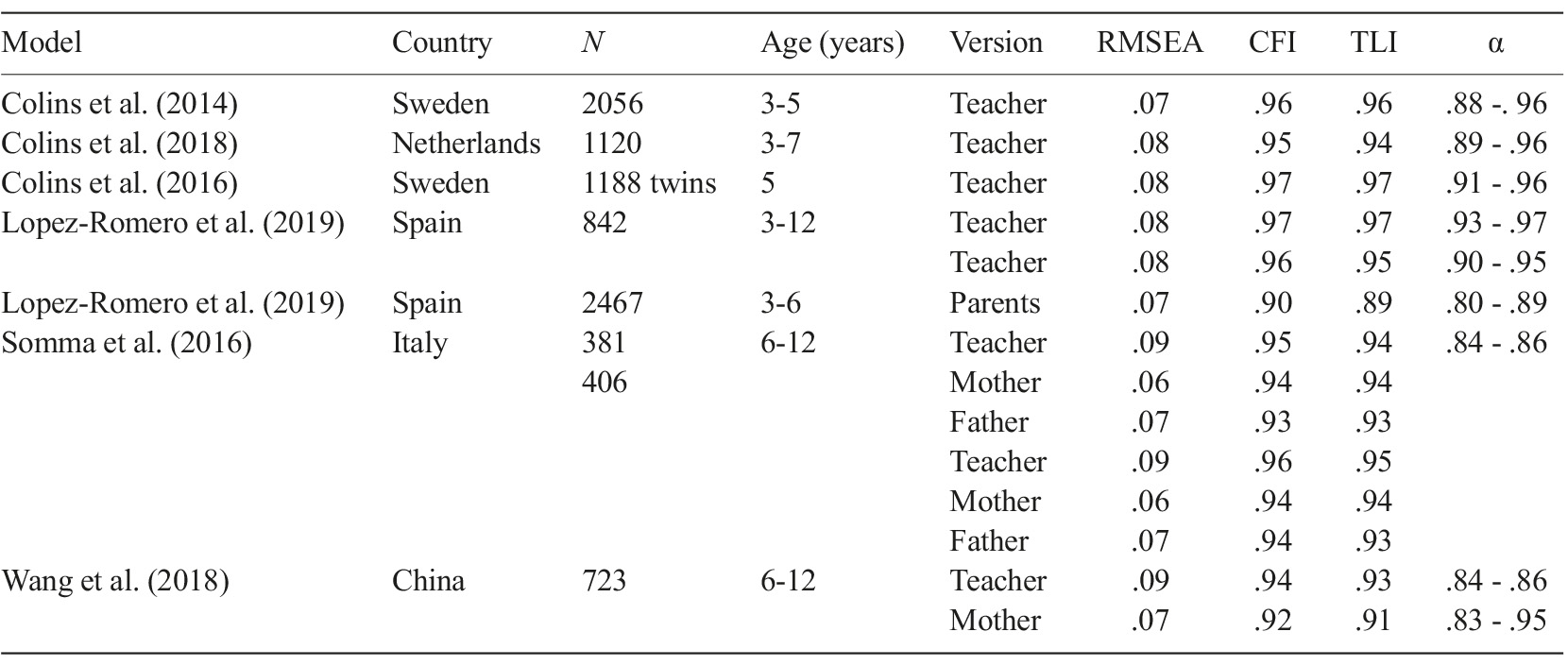

The psychometric properties of the teacher version of the CPTI (see Table 1) have been tested in different samples (Colins et al., 2019), countries, and languages (Colins et al., 2014, 2016, 2018; López-Romero et al., 2019; Somma et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018), and the three-factor structure has been consistently confirmed with good to excellent internal consistency. Importantly, this was not only the case for the CPTI teacher’s version but also for the parental version. As far as the CPTI teacher’s version is concerned (in terms of convergent validity), the three factors have (1) a positive and significant correlation with behavioral problems, symptoms of hyperactivity and attention deficit, proactive and reactive aggression; and (2) a negative correlation with easy temperament, even when adjusted for sociodemographic variables (see Colins et al., 2014, 2016, 2018). On the other hand, regarding the parent’s version, the three subscales of CPTI are significantly associated with external criteria such as conduct problems, reactive aggression and proactive aggression, hyperactivity, and lack of fear (Lopez-Romero et al., 2019). Additionally, Wang et al. (2018) found positive associations between psychopathy measures and constructs closely related to extraversion, such as dominance.

Table 1 Model fit and internal consistency results reported for CPTI

Note. RMSEA=Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; CFI=Comparative Fit Index; TLI=Tucker Lewis Index.

In this study, we aim to analyze the factor structure of the CPTI for Portuguese children aged 3 to 6 years old, as well as examine its internal consistency and validity. Given the lack of instruments to assess psychopathic traits during childhood, the present study allows us a possible early identification of psychopathic traits included in the CPTI. The present study may also contribute to the literature by testing whether the CPTI performs comparably to other countries’ versions (e.g., Sweden). Furthermore, we intend to test the criterion validity via the correlation with an alternative measure of the Impulsivity subscale of the Children Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ). Studies indicate (Figueiredo et al., 2022) that the total scores of the Inventory of CU traits (ICU; Frick, 2004), a measure developed to measure CU traits in children and adolescents, were correlated positively with the CPTI total scores, as well as with other dimensions of CU traits, such as the affective, interpersonal, and behavioral dimensions. As far as we know, this is the first time that the CPTI criterion validity is being tested with a temperament measure. This is particularly important since the child’s temperament is observable through behavior in daily situations, especially impulsivity in reaction to everyday events. Additionally, we aimed to test the convergent validity of CPTI by examining its relationship with Irritation/Frustration and Inhibited Control subscales of the CBQ.

Method

Participants

Children without need for special educational and aged between 3 and 6 years were eligible to participate in the study. The sample is composed of 264 children (43.2% female, n=114), aged between 3 and 6 years (M=4.78, SD=.60). Table 2 shows the sample characteristics.

Measures

Psychopathic Personality Traits.

Child Problematic Traits Inventory (CPTI; Colins et al., 2014). The CPTI was developed to assess psychopathic personality traits in children between 3 and 12 years of age. It is a 28-item questionnaire based on the three-factor model of psychopathy (Cooke & Michie, 2001). The Interpersonal/GD psychopathy dimension is composed of eight items (e.g., “Thinks that he or she is better than everyone on almost everything”). The affective/CU psychopathy dimension is composed of 10 items (e.g., “Never seems to feel bad for things that he or she has done”). The behavioral/INS psychopathy dimension is composed of 10 items (e.g., “Provides himself or herself with different things very fast and eagerly”). Participants were instructed to answer based on how the child typically behaves, responding on a four-point Likert scale: 0=Does not apply at all; 1=Does not apply well; 2=Applies fairly well; and 3=Applies very well (Colins et al., 2014). Teachers are reliable informers of young children’s personality traits (e.g., Hampson & Goldberg, 2006) since they are familiar with the child across various situations in the school context. Thus, they are in a perfect position to make normative judgments on behavior because of their extensive experience with children of the same age groups (Somma et al., 2016).

Temperament.

Child Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart et al., 2001). The CBQ was developed to provide a highly differentiated temperament assessment in young children between 3 and 7 years, following the constitution-based approach with individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation (Lopes, 2011). The CBQ scales are organized in three dimensions: Negative Affectivity, Extroversion, and Effort Control. The CBQ short version (94 items) represents a viable alternative for researchers with limited time and resources to administer the Standard form (195 items) while allowing their integration into multivariate research studies. The CBQ short version comprises 15 scales, composed of six to eight items each: Activity Level, Anger/Frustration, Approach, Attentional Focusing, Discomfort, Falling Reactivity & Soothability, Fear, High-Intensity Pleasure, Impulsivity, Inhibitory Control, Low-Intensity Pleasure, Perceptual Sensitivity, Sadness, Shyness, and Smiles and Laughter. Each item needs to be answered using a seven-point Likert scale: 1=Very False; 2=Fairly False; 3=Slightly False; 4=Neither True nor False; 5=Untrue; 6=Fairly True; 7=Very True. There is also an option of Not Applicable (quoted with 0). For this study, only three CBQ scales were applied: Anger/Frustration, Impulsivity, and Inhibitory Control. The Anger/Frustration scale assesses the negative affect related to ongoing work interruption. Impulsivity assesses the speed of response. Inhibitory Control assesses the ability to plan and suppress inappropriate responses to instructions or in new or uncertain situations (Putnam & Rothbart, 2006).

Procedures

To translate the CPTI into Portuguese, the guidelines suggested by Brislin (1970) and Sireci et al. (2006) regarding forward and backward translations of psychometric tools were followed. Preschool institutions in the Northern region of Portugal were selected based on proximity, accessibility, and availability. The directors of 27 institutions were contacted, and the research procedure was explained to the directors and teachers of the 20 institutions that agreed to collaborate in the study. Informed consent was provided to parents of the eligible children of the 299 informed consents delivered, 284 were signed and returned, and complete questionnaires were returned for the 264 children and included in the analysis. The children’s teacher answered the sociodemographic, CPTI, and CBQ questionnaires. All procedures followed the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee. The ethical board of the University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro approved all the materials and the study protocol (71A/CE/2018).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS v26 (IBM Corp, 2019) and MPLUS. Following Bryant and Yarnold’s (1995) indications of a minimum sample size for a more rigorous factor analysis, the sample estimation followed a subject-variable ratio, i.e., a subject-variable ratio of no less than 5 participants for each item (5:1). The CPTI scale consisted of 28 items, so the required sample size was at least 140 participants. However, at the end of the data collection process, it was possible to obtain a ratio of 9:1 (264 participants), which improved analytical stability. A confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA) was conducted in MPLUS to test the adequacy of the original three-factor CPTI model (Colins et al., 2014) in the Portuguese sample, using the mean and variance-adjusted weighted least squares estimator appropriate for ordinal items (Flora & Curran, 2004).

Data from the participants with missing items in the CPTI were withdrawn (n=6), so the analysis was conducted with 258 cases. Model fit was assessed using the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), as recommended by Sharma et al. (2005). RMSEA values below .05 indicate a good adjustment, while values between .05 and .08 indicate an acceptable fit. A CFI and TLI index of .95 or higher indicates an excellent fit and a CFI and TLI index of .90 or higher indicates a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The internal consistency analysis of the factors was performed using Cronbach’s alpha, the average item correlation (AIC), and the item-total correlation (ITC). The alpha coefficients were interpreted as follows: <.60=insufficient; .60 to .69=marginal; .70 to .79=acceptable; .80 to .89=good; and .90 or higher=excellent (Barker et al., 2002). The Pearson correlation between the three CPTI scales and between each scale and the total score was computed. The criterion validity was obtained through the Steiger Z test, calculated using an online calculator (http://www.psychmike.com/dependent_correlations.php; Hoerger, 2013). The convergent validity was performed using the SPSS 26.0 software. Zero-order correlations - and, for the CPTI factors, partial correlations (controlling for age, gender, and the other two CPTI dimensions) - between the CPTI scores and external variables (Irritation/Frustration subscale and the Inhibited Control subscale of the CBQ) were computed.

Results

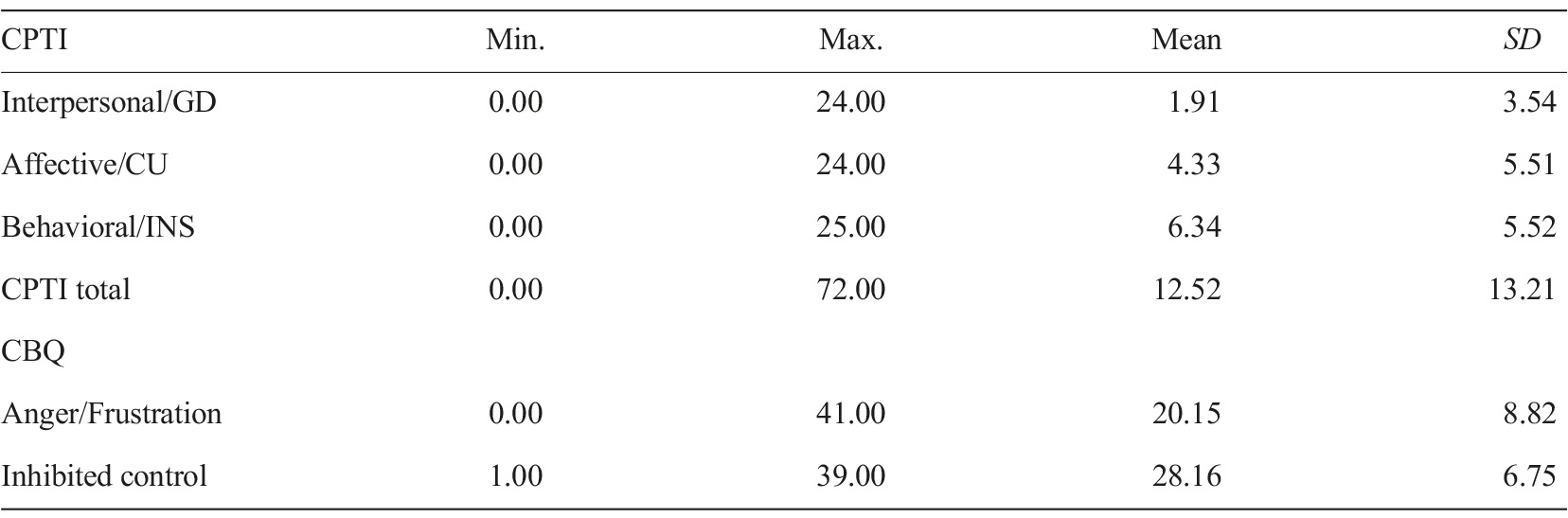

Descriptive statistics for the CPTI and CBQ scores are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3 Scores of the CPTI and CBQ

Note. CPTI, child problematic traits inventory; CBQ, children behavior questionnaire; GD, grandiose-deceitful; CU, callous-unemotional; INS, impulsive-need of stimulation.

Confirmatory factor analysis

CFA revealed that the fit of the proposed CPTI model ranged from acceptable (RMSEA=.076) to good (TLI=.96; CFI=.96).

Internal consistency of CPTI dimensions

Cronbach’s alpha for the three CPTI dimensions and CPTI Total score were .89 (Interpersonal/GD), .92 (Affective/CU), .88 (Behavioral/INS), and .95 (CPTI Total score), meaning values above .80 for all dimensions. Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was .95. Table 4 shows the means and standard deviations of the items, Cronbach’s alpha for the dimensions, average item correlation (AIC), and item-total correlation (ITC).

Table 4 Items’ means and standard deviations, average item correlation, item-total correlation

Note. AIC, average item correlation; ITC, item-total correlation; SD, standard deviation; GD, grandiose-deceitful; CU, callous-unemotional; INS, impulsive-need of stimulation.

The correlation between the three CPTI scales and between each scale and the total score was highly significant (see Table 5).

Criterion validity

The Total CPTI and the three dimensions of CPTI were significantly correlated with the alternative measure of Impulsiveness - CBQ Impulsivity subscale (r=.37Total; .29Interpersonal; .26Affective; .45Behavioral). The Steiger Z test revealed that the Behavioral dimension of the CPTI had a significantly stronger association with the CBQ Impulsivity subscale (Z=.43, p=.015) compared to the Interpersonal/GD dimension of the CPTI (Z=-3.80, p<.001) or the Affective dimension of the CPTI (Z=-4.52, p<.001).

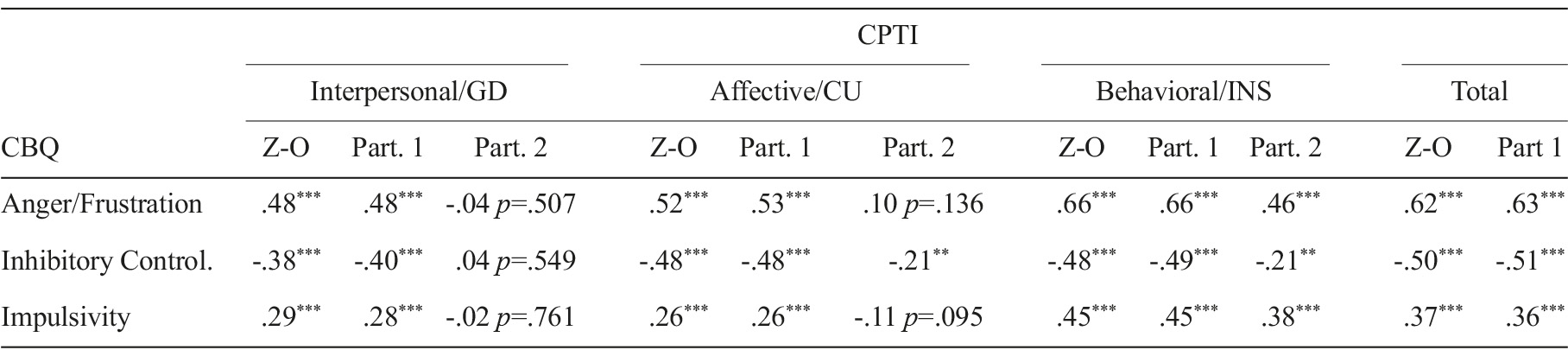

Convergent validity

As expected, all CPTI scores (total and dimensions) were significantly related to CBQ Anger/Frustration (positive relation) and Inhibitory Control (negative relation), even after controlling for age and gender (Table 6). After controlling for age and gender to facilitate comparability with other studies, as well as the other two CPTI dimensions, the CPTI behavioral/INS dimension remained significantly related to both CBQ scores, the CPTI affective/CU dimension only remained significantly related to CBQ Inhibitory Control. The interpersonal/GD dimension was no longer significantly related to the CBQ scores.

Table 6 Zero and Partial Order Correlations Between the Total CPTI, the Three Dimensions, and the Alternative Measures of the CBQ

Note. Z-0 - Zero-order correlations; Part 1 - Partial correlations controlling age and gender; Part 2 - Partial correlations controlling age, gender, and other subscales GD, grandiose-deceitful; CU, callous-unemotional; INS, impulsive-need of stimulation; CPTI, child problematic traits inventory. **p<.01; ***p<.001.

Discussion

The Child Problematic Traits Inventory (CPTI) is a reliable tool to assess psychopathy dimensions in early childhood, especially in children with ages between 3 and 12 years through reports of teachers/educators (Colins et al., 2014). In this study, we aimed to test the validity and the internal consistency of the CPTI for Portuguese children with ages between 3 and 6 years old using the Anger/Frustration, Impulsivity, and Inhibitory Control scales of the Children Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ).

In this study, the Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA) sought to study if the adequacy of fit of the original CPTI model showed an acceptable to good model fit. Other validation studies showed acceptable adjustments of the CPTI structure to their samples (Colins et al., 2014, 2016, 2018; Somma et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). The reliability of the CPTI total score and its dimensions was found good to excellent when applied to the Portuguese sample, indicating the instrument’s suitability to administer in Portuguese children aged 3 to 6 years. The criterion validity was also confirmed since the CPTI total, and the dimensions are significantly correlated with an alternative measure of Impulsiveness - CBQ Impulsivity subscale. Of the CPTI, comparing the Interpersonal/GD or Affective/CU dimension to the Behavioral/INS dimension, it has a significantly strong association with the CBQ Impulsivity subscale, confirming the initial hypothesis. Additionally, we also found evidence of convergent validity since, as expected, zero-order correlations have shown that the CPTI total and its dimensions are significantly and positively correlated with the CBQ Anger/Frustration subscale and negatively correlated with the CBQ Inhibitory Control subscale, which was also verified that these correlations remain when controlling for age and gender. Partial correlations between each of the dimensions of the CPTI, the CBQ Anger/Frustration subscale, and the CBQ Inhibitory Control subscale when controlling age, gender, and other two dimensions of the CPTI are lower than the zero-order correlations.

The Inventory of Callous-Unemotional traits (ICU) has been a measure highly used in younger populations to detect the possibility of preventing aggressive behavior through adolescence and adulthood, especially as fundamental for psychopathic personality (Frick et al., 2014), however ICU alone might not be able to predict conduct problems since psychopathic personality involves interpersonal, affective, and behavioral traits. This study showed that the CPTI is a reliable research tool that can assist professionals in the Portuguese context, as its use might be optimal since it involves the three dimensions associated with psychopathic personality and assesses children as young as three years. However, once more findings have been replicated, it will be helpful for clinical decision-making (Colins et al., 2019) as his is an affordable and low-time-consuming tool, allowing viability for its use. Also, it gives a different perspective on the relation between psychopathy factors and external correlates (Colins et al., 2019).

Still, there are some limitations to this study. Firstly, the sample was confined to 3 to 6-year-old children which generalization for other community-based youth samples is quite limited. Secondly, variables were assessed using self-report measures, in which individuals can omit important data. Thirdly, it was used convenience sampling which can lead to sampling biases. Future studies are needed to test the structure of CPTI’s reliability and validity for children under six years. The development and validation of the CPTI is a vital first step toward a new field of research on early childhood development of psychopathic personality, its risk factors, and its stability and change over time (Colins et al., 2014).