Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Arquivos de Medicina

versão On-line ISSN 2183-2447

Arq Med vol.29 no.1 Porto fev. 2015

INVESTIGAÇÃO ORIGINAL

Linguistic and cultural adaptation into European Portuguese of swal-qol and swal-care outcomes tool for adults with oropharyngeal dysphagia

Validação da versão Portuguesa do questionário swal-qol em doentes com patologia oncológica da cabeça e pescoço

Eva Bolle Antunes1, Daniela Vieira1, Mário Dinis-Ribeiro2

1Universidade Fernando Pessoa, Porto, Portugal

2Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto, Portugal

ABSTRACT

Dysphagia can lead to symptoms like malnutrition, dehydration and aspiration pneumonia, and knowledge about the swallowing disorder can improve the patients quality of life. This paper reports the adaptation into European Portuguese of SWAL-QOL, which assesses the quality of life, and SWAL-CARE, for the quality of care, in swallowing disorders. The adaptation of SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE encompassed four steps, which were overseen by the researchers for clinical, linguistic and cultural equivalence: translation into European Portuguese; comparative review by a panel of experts; back-translation and approval by author of the original version; pre-test. After the discussion of specific concepts of the first translation, we had consensus version 1 in Portuguese, which was presented to the panel of experts. The resulting consensus version 2 was remitted for back-translation, then revised and compared with the original English surveys. Subsequently, the pre-test aimed to check the cultural equivalence, and the comprehension of the wording of the questions and the scales. The final version was obtained, after the researchers discussed some clinical and linguistic issues. SWAL-QOL-PT and SWAL-CARE-PT have linguistic as well as cultural equivalence with the original English version, and can be submitted to psychometric testing.

Key-words: deglutition, deglutition disorders, quality of life

RESUMO

A disfagia pode conduzir a sintomas como malnutrição, desidratação e pneumonia de aspiração, e o conhecimento sobre a perturbação da deglutição pode melhorar a qualidade de vida dos pacientes. Este artigo relata a adaptação para o português europeu dos instrumentos SWAL-QOL, que avalia a qualidade de vida, e SWAL-CARE, para a qualidade dos cuidados prestados, relativamente às perturbações da deglutição. A adaptação do SWAL-QOL e do SWAL-CARE englobou quatro etapas, que foram supervisionadas pelos pesquisadores para a equivalência clínica, linguística e cultural: tradução para português europeu; revisão comparativa por um painel de especialistas; retroversão e aprovação pelos autores da versão original; e pré-teste. Após discussão de conceitos específicos da primeira tradução, chegou-se à versão consenso 1 em português, que foi apresentada ao painel de especialistas. A versão consenso 2 resultante foi enviada para retroversão, e depois revista e comparada com os questionários originais em inglês. Subsequentemente, o pré-teste teve como objetivo verificar a equivalência cultural, e a compreensão da formulação dos itens e das escalas. A versão final foi obtida, após discussão pelos pesquisadores de questões clínicas e linguísticas. O SWAL-QOL-PT e o SWAL-CARE-PT têm equivalência linguística e cultural com a versão original em inglês, e podem ser submetidos a testes psicométricos.

Palavras-chave: deglutição, perturbações da deglutição, qualidade de vida

Introduction

The reported occurrence of dysphagia is variable, reaching up to half or more of the studied populations, depending on the investigation design, the methods and timing of assessment, the aetiology of the impairment, and co-morbidities.1 Dysphagia can cause malnutrition, dehydration and aspiration pneumonia, in diverse degrees of severity.2-4 it can also have a negative psychosocial impact, and contributes to personal, social, and economic costs that should not be ignored.5,6 Therefore, our motivation was to contribute to the perception of the impact that dysphagia may have on the patient and carers. SWAL-QOL is a 44-item tool that assesses ten quality of life domains (food selection, burden, mental health, social functioning, fear, eating duration, eating desire, communication, sleep and fatigue, and symptom frequency), scored in a five-point Likert scale. SWAL-CARE is a 15-item tool that assesses three quality of care domains (clinical information, general advice and patient satisfaction), scored in a six-point Likert scale. Whenever possible, both surveys are to be completed by the patient and it should take an average of 14 minutes to complete SWALQOL, and 5 minutes for SWAL-CARE(7). The aim of this work was to accomplish the linguistic and cultural adaptation of SWAL-QOL, and of SWALCARE, into European Portuguese.7-9

Currently, we know of 5 versions: Dutch,10 french,11 Brazilian Portuguese,12 Chinese,13 and Swedish.14 The whole adaptation process into European Portuguese involves two main phases, which were devised according to some sources:15-19 1) linguistic and cultural adaptation; 2) validity and reliability. We have concluded the first phase, which we account for here. In Portugal, properly conceived dysphagia assessment protocols are scarce; therefore, it seemed pertinent to adapt these two surveys, following a clear procedure, which will culminate in their validation. Moreover, the translation of existing tools into other languages supports the progress of research through the exchange of information, and transcultural studies.19

Methods

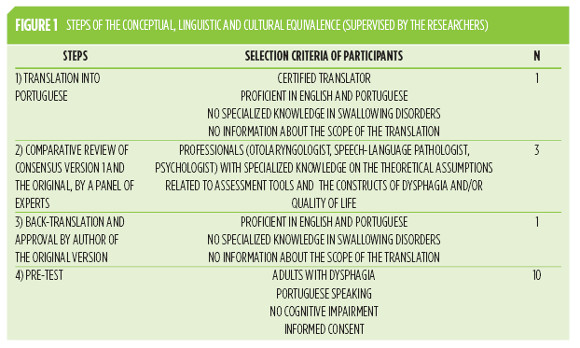

This project was set in motion after the expressed consent of the main author. To perform the linguistic and cultural adaptation of SWAL-QOL, and SWAL-CARE into European Portuguese, a method of translation and back-translation, with a pre-test, was used. This process encompassed four key steps (Figure 1), which were overseen by the researchers for clinical and linguistic equivalence, and which will be described with more detail in the results section. The original version was sent to a certified translat or proficient in English and Portuguese, but with no specialized knowledge in swallowing disorders, and with no information about the scope of the translation. After revision by the researchers, this led to consensus version 1, which was reviewed by a panel of experts who have specialized knowledge on the theoretical assumptions related to assessment tools and the constructs of dysphagia and/or quality of life: an otolaryngologist, a speech-language pathologist, and a psychologist. Subsequently, the back-translation was performed by a proficient individual in English and Portuguese, with no specialized knowledge in swallowing disorders, and no information about the scope of the translation. The author of the original version accepted this back-translation.

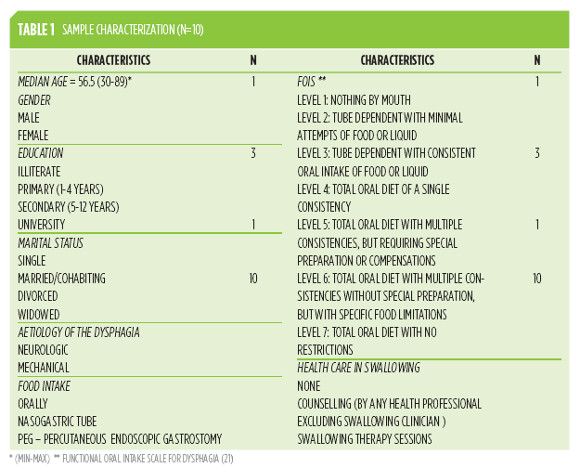

A cognitive interview approach was necessary at this stage for a qualitative analysis of the individual processes inherent to the understanding of this survey, and the value of this adaptation. Therefore, a pre-test was conducted in two Portuguese hospitals, in 2009, with a sample of 10 individuals with dysphagia since at least one month, characterized for age, gender, education, marital status, aetiology of the dysphagia, oral or non-oral food intake, FOIS -functional Oral intake Scale for Dysphagia (Table 1

). FOIS is rated in a seven-point ordinal scale according to patients and caregivers reports (level one corresponds to the most severely impaired and level seven to no impairment), 20 and it was used to characterize the patients swallowing performance, with the intent of covering all levels.

Patients that participated in the pre-test were adults with dysphagia due to neurological disorders or head and neck cancer, with Portuguese as the mother language, without cognitive impairment, and able to fill in the informed consent, according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The group of participants were within a wide range of ages (30-89), and all levels of schooling, including a majority with less that 4 complete years of education, which is important for ascertaining comprehension of the questions. They completed a written questionnaire under the supervision of the researchers, having the opportunity to present and discuss orally any emerging issues. During the interviews, the duration of both surveys (including comments and remarks) and the type of help given were registered. The participants were asked whether they wanted to answer the surveys on their own, because, even though it is to be completed by the patient whenever possible, the researchers were interested in conducting a thought reflection.

Results

Translation into Portuguese and consensus version 1

The researchers and the certified translator discussed some specific technical concepts of the first translation. Some terms were incorrectly translated by the translator and were unrelated to swallowing, e.g., phlegm was initially expressed in Portuguese as fleuma which means indifference, tranquillity, moderation. Thus, the researchers corrected this word, which resulted in a synonym in the back-translation (expectoration). The wording of the Likert scales was challenging, because the literal translation resulted in meanings that were too similar amongst each scale point. A few adaptations were made so as to make the concepts more distinguishable, and during the validation and reliability studies (the second phase of this project) we will have the opportunity to test how they behave. After this, we had theconsensusversion1of SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE in Portuguese.

Comparative review and consensus version 2

Consensus version 1 was presented to the multidisciplinary panel of experts, who also had access to the original English version for the linguistic, cultural, and health-related comparison and analysis. Considering their propositions, the researchers own perspectives and the fact that, in contrast with other European countries, the level of literacy of the Portuguese population is very low,21 a few corrections were made at this point until consensus version 2 was reached. There were adjustments in the wording of the questions in view of the characteristics of the language, the target population, and cultural differences, e.g., tomato juice was omitted in the examples of liquid consistencies. In Portugal, it is not usual to eat apple sauce, so the word chosen by the researchers translates into jam. These adaptations were considered to be non-detrimental to the purpose of the original version.

Back-translation

This second version was remitted for back-translation and approval by author of the original version, which was compared with the original English surveys, and discussed by the researchers for the final clinical and linguistic revision. Gag would translate into a technical term that might not be understood by the target population, and the back-translation demonstrated that there was no semantic equivalence, because the result was vomiting. Therefore a more common word was chosen, i.e., vómito in Portuguese. This retroversion was approved by the author of the original, who made no requests for alterations. At this point, the researchers accepted consensus version 3 in Portuguese, which was used for the pre-test.

Pre-test and Final consensus version

The pre-test aimed to check the cultural equivalence, and the comprehension of the wording of the questions and the scales. The final version was obtained, after the researchers discussed some clinical and linguistic issues. All the patients asked for help in reading and writing down their answers. The median of time necessary to answer was 15 minutes, and the maximum was 25 minutes. They understood the survey, and this was established by confirming the certainty of their answers and by their comments that indicated that they identified themselves with what was being asked.

There are two sentences with a double meaning, both using saliva or phlegm, and most of the participants emphasized or referred to only one of the symptoms. The sentence I never know when I am going to choke revealed to be dubious because it includes a word also used in the scale: never. Some people tended to answer never if they never knew when they would choke, but in fact they wanted to say that they almost always never knew when this was going to happen. The researchers decided to maintain the phrasing with the same meaning, because if any change was to be made, the direction of the scale would be reversed for this item.

The participants in the pre-test wondered what the relation with swallowing disorders was, when they read the statement I worry about getting pneumonia. in order to respect the conceptual meaning of the survey, no changes were made. Some of the patients reported that the surveys were a bit lengthy, but were not too anxious by this. The measurement of outcomes was not the intention of this study, but a preliminary analysis of SWAL-CARE indicates that results tend to be noticeably poor in what concerns quality of information and satisfaction with care for dysphagia (only two of the patients had had swallowing therapy sessions).

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to carry out the conceptual, linguistic and cultural equivalence of SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE into European Portuguese, following recommended steps:15-19 translation in Portuguese; review by a panel of experts; back-translation; comparison with the original and modified versions in Portuguese; pre-test; clinical and linguistic revision for the final adapted versions; approval of the Portuguese versions -SWAL-QOL-PT and SWAL-CARE-PT.

The steps before the pre-test were useful for comparisons between the temporary versions, and adjustments were made. We concluded that individuals of all groups were able to understand the surveys, and that the equal distribution of a etiologies did not influence the comprehension of the questionnaires. All levels of swallowing functional impairment (FOIS)20 were contemplated in our sample, and the patients related to the constructs. nonetheless, those who were tube dependent did not identify themselves with some of items within the domains concerning eating duration, symptom frequency and fear. This can be useful in comparison with future quality of life scores since it is also a perception of the patients impaired swallowing ability.

In Portugal, swallowing therapy by a specialized clinician is infrequent and, during the pre-test when answering SWAL-CARE, most people tended to think about health care in general or about counseling provided by other health professionals (medical doctors, nurses or nutritionists), while hospitalized and during follow-up. Therefore, results will have to be interpreted with caution in future studies, and the type of care provided should be considered. We realized that there was a lack of information concerning dysphagia, namely, people do not relate the risk of pneumonia with aspiration by swallowing disorders.

SWAL-QOL-PT and SWAL-CARE-PT have linguistic and cultural equivalence with the original English version. They are ready for validation and reliability, and the gathering of normative data, so that they can be used not only by researchers, but also by clinicians. This psychometric validation of the instruments is essential and will be available soon. Finally, there is commonly the perception that feeding has a noteworthy social and cultural dimension in Portugal, and this adapted survey will be useful for future researches on this fact.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the panel of experts composed by Eurico Monteiro, Susana Vaz Freitas, and Inês Gomes, as well as Cláudia Antunes for back-translating the surveys. Likewise, the authors show appreciation to Colleen McHorney for consenting to the use of SWAL, and to John Rosenbek for the credit and encouraging words. We also thank all the patients who voluntarily collaborated in this study.

References

1. ASHA - American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Roles of speech-language pathologists in swallowing and feeding disorders: Technical report. ASHA, 2001. [ Links ]

2. Pulia-Rogus N, Robbins, J. Approaches to the rehabilitation of dysphagia in acute poststroke patients. Semin Speech Lang. 2013;34(3):154-169. [ Links ]

3. Martino R, Foley N, Bhogal S, Diamant N, Speechley M, Teasell R. Dysphagia after stroke: incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications. Stroke. 2005;36:2756-63. [ Links ]

4. Wilkins T, Gillies R, Thomas A, Wagner P. The prevalence of dysphagia in primary care patients: a hames net reearch network study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:133.50. [ Links ]

5. Farri A, Accornero A, Burdese C. Social importance of dysphagia: its impact on diagnosis and therapy. Ata otorhinolaryngol ital. 2007;27:83-6. [ Links ]

6. Chichero JA, Altman KW. Definition, prevalence and burden of oropharyngeal dysphagia: a serious problem among older adults worlwide and the impact on prognosis and hospital resources. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2012;72:1-11. [ Links ]

7. McHorney CA, Robbins J, Lomax K, Rosenbek JC, Chignell K, Kramer AE, et al. The SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: III. Documentation of reliability and validity. Dysphagia. 2002;17(2):97-114. [ Links ]

8. McHorney CA, Bricker DE, Kramer AE, Rosenbek JC, Robbins J, Chignell KA, et al. The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: I. Conceptual foundation and item development. Dysphagia. 2000;15(3):115-21 [ Links ]

9. McHorney CA, Bricker DE, Robbins J, Kramer AE, Rosenbek JC, Chignell KA. The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: II . Item reduction and preliminary scaling. Dysphagia. 2000;15(3):122-33. [ Links ]

10. Bogaardt H, Speyer R, Baijens L, Fokkens W. Cross-cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Dutch Version of SWAL-QoL. Dysphagia. 2009;24(1):66-70. [ Links ]

11. Khaldoun E, Woisard V, Verin E. Validation in French of the SWAL-QOL scale in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroen clin biol. 2009;33(3):167-71. [ Links ]

12. Portas J. Validação para a língua portuguesa-brasileira dos questionários: qualidade de vida em disfagia (Swal-qol) e satisfação do paciente e qualidade do cuidado no tratamento da disfagia (Swal-care). Portal domínio público - biblioteca digital desenvolvida em software livre: FAP/Oncologia; 2009. [ Links ]

13. Lam PM, Lai CK. The validation of the Chinese version of the Swallow Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (SWAL-QOL) using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Dysphagia. 2011;26(2):117-24. [ Links ]

14. Finizia C, Rudberg I, Bergqvist H, Ryden A. A cross-sectional validation study of the Swedish version of SWAL-QOL. Dysphagia. 2012;27(3):325-35. [ Links ]

15. Aaronson N, Alonso J, Burnam A, Lohr KN, Patrick DL, Perrin E, et al. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual life res. 2002;11(3):193-205. [ Links ]

16. Ferreira L. Criação da versão Portuguesa do MOS-SF-36, Parte I - adaptação cultural e linguística. Acta Med Port. 2000;13:55-66. [ Links ]

17. Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and propose guidelines. J clin epidemiol. 1993;46:1417-32. [ Links ]

18. Perneger T, Leplége A, Etter J. Cross-cultural adapttion of a psychometric instrument: two methods compared. J clin epidemiol. 1999;52:1037-46. [ Links ]

19. MAPI MI-. International linguistic validation of questionnaires and patients documents. http://www.mapigroup.com/2008 [cited 2008]. [ Links ]

20. Crary MA, Carnaby Mann GD, Groher ME. Initial psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for dysphagia in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1516-20. [ Links ]

21. Ferrão J, Marques T. População, qualificaçõs e capital cultural. In: CA Medeiros, editor. Geografia de Portugal, Sociedade, Paisagens e Cidades. Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores; 2005. [ Links ]

Daniela vieira

Universidade Fernando Pessoa – Praça 9 de abril, 349, 4249-004 Porto, Portugal; locker 109. E-mail: dvieira@ufp.edu.pt

Data de recepção / reception date: 22/08/2014

Data de aprovação / approval date: 01/12/2014