Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista Portuguesa de Educação

Print version ISSN 0871-9187

Rev. Port. de Educação vol.29 no.1 Braga June 2016

https://doi.org/10.21814/rpe.8713

ARTIGOS

The importance of transition planning for special needs students

A importância da planificação da transição para os alunos com necessidades especiais

La importancia de la planificación de la transición para los alumnos con necesidades especiales

James R. Pattoni Min Kyung Kimii

i University of Texas at Austin, USA

ii East Tennessee State University, USA

ABSTRACT

This article discusses the transition planning process for students with special needs who are preparing to leave secondary school. The importance of doing this has strong face validity, as one of the outcomes of education should be preparing students to become productive and contributing citizens. A systematic transition process contributes to the probability that students will have better post-school outcomes. This article addresses five major areas. First, an explanation of what might be considered successful adult functioning is offered. Second, the key elements/concepts associated with the transition process are discussed. Third, a brief summary of the literature on transition is provided. Fourth, a model for considering how to conceptualize the transition planning process is presented with the idea that following a system like the one discussed can be very useful for addressing the transition needs of students. Lastly, a list of how the school, family, and student can contribute to this process is provided.

Keywords: Transition; Transition planning process; Post-school outcomes; Adult functioning

RESUMO

Este artigo analisa o processo de planificação da transição para a vida pós-escolar dos alunos com necessidades especiais. Este processo tem uma forte validade social, uma vez que uma das finalidades da educação é preparar os alunos para uma cidadania plena. Um processo de transição sistemático contribui para o aumento da probabilidade de estes alunos obterem melhores resultados no período pós-escolar. Este artigo aborda cinco aspetos fundamentais deste processo. No primeiro apresenta uma explicação do que pode ser considerado adequado para um funcionamento bem sucedido como adulto. No segundo analisa os elementos-chave/conceitos associados ao processo de transição. No terceiro é apresentado um breve resumo da literatura sobre transição. No quarto é apresentado um modelo que permite conceptualizar o processo de planificação da transição, considerando que a existência de um modelo deste tipo é útil na resposta às necessidades destes alunos. Por último, são apresentados possíveis contributos da escola, família e alunos para a planificação do processo de transição.

Palavras-chave: Transição; Planificação do processo de transição; Resultados no período pós-escolar; Funcionamento do adulto

RESUMEN

El presente artículo pretende analizar el proceso de planificación de la transición a la vida postescolar de los alumnos con necesidades especiales. Este proceso tiene una sólida validez social, una vez que uno de los objetivos de la educación es preparar a los alumnos para una ciudadanía plena. Un proceso de transición sistemático contribuye a un incremento de las posibilidades de que estos alumnos obtengan unos mejores resultados en el período postescolar. Este artículo aborda cinco aspectos fundamentales de este proceso. El primero constituye una exposición de lo que se puede considerar adecuado para un funcionamiento exitoso del adulto. En el segundo se analizan los elementos-clave/conceptos asociados al proceso de transición. En el tercero se realiza una breve síntesis de la literatura existente sobre la transición. En el cuarto se presenta un modelo que permite conceptualizar el proceso de planificación de la transición, considerando que la existencia de tal modelo resulta útil para responder a las necesidades de estos alumnos. Finalmente, se aborda la contribución que pueden dar la escuela, la familia y los alumnos a una planificación del proceso de transición.

Palabras-clave: Transición; Planificación del proceso de transición; Resultados en período postescolar; Funcionamiento del adulto

Introduction

Transitions are part of everyone’s life. Some are predictable while others occur more spontaneously. Although this article is focused on the transition from school to life after school, it is worthwhile to think about transitions as a lifelong reality (see Price & Patton, 2003), as dramatic transitions will occur early in life as well as later in life.

Transition is a concept that implies change and movement. For students who are in school, change and movement occur throughout their school careers. Without question, many transitions occur on a daily basis (e.g., moving from one task to another within a classroom situation); other transitions involve major changes (e.g., moving from primary school to secondary school). While all of these transitions are worthy of discussion, this article will focus on one particular transition that we feel is especially important for special needs students. This transition is the one when formal schooling ends and life after school begins.

The overall theme that is promoted in this article is the fact that, with appropriate transition assessment and planning, special needs students are more likely to have what is referred to as a "seamless" transition to adulthood. It is true that some students can achieve a successful transition from school to life after school without assistance provided by school-based personnel. Our point is that the probability of success is improved when we do not leave this important transition to chance.

This article will cover the following topics. The first section presents ideas related to what "successful adult functioning" means. The second section provides a discussion of the basic concepts related to transition, as this concept applies to students who are about ready to leave school. The third part of the article reviews existing literature in terms of what we know about transition services. The fourth part of the article introduces a transition planning process that can serve as a framework for implementing a successful transition program for special needs students. This section offers a number of recommendations for school-based personnel to consider. The last section highlights the major points that we believe are key to the successful transition of youth to life when school ends.

1. What is successful adult functioning?

To understand the importance of good transition planning, it is useful to consider the outcomes associated with successful functioning in adulthood, which is a major goal of transition planning efforts. Figure 1 depicts a simple conceptualization of the adulthood implications of transition. A brief explanation of the model, starting at the far right, follows.

In this model the ultimate outcome for which all transition efforts should be directed is to help create lives that are characterized by the concept of personal fulfillment. This concept relates closely to the notion of quality of life, as discussed by Halpern (1993). Halpern suggested that quality of life – or personal fulfillment – relates to three elements: happiness (transient state of affect), satisfaction (feelings and behavior patterns associated with different adult roles), and sense of general well-being (enduring sense of satisfaction with one’s life). We believe that all that school-based professionals do with students should be guided by the overriding theme of enhancing the students’ quality of life by imparting the means for them to be personally fulfilled.

To enjoy some sense of personal fulfillment, an individual must be reasonably successful in meeting the challenges of everyday life, whether at work, at home, in school, or in their community. Various references (Cronin, Patton, & Wood, 2007; Wandry, Wehmeyer, & Glor-Scheib, 2013) provide listings of the major demands encountered in adulthood. People who feel that they are personally fulfilled do not always deal successfully with the day-to-day issues that arise in their lives; however, they are more likely than other individuals to handle those issues successfully most of the time.

How does one become competent to deal with the daily challenges of life? Three factors are essential. First, an individual must have knowledge of an array of facts, procedures, and events that are part of his or her post-school environments. Second, the individual needs to acquire specific skills typically demanded in those settings in which the person must function. Third, the person must identify, access, and use a host of supports and/or services that will be of great assistance in dealing with everyday events – often, supports are provided by family, friends, and other people who are part of the person's life. The interesting point is that everybody uses supports and services throughout life and the idea of seeking such support is a natural part of life.

As can be seen in Figure 1, four factors share the responsibility for preparing special needs students for adulthood. These four elements – school, family, the student, and adult services – are intricately involved in the transition process. Ideally, efforts to prepare students for dealing with the everyday issues of adulthood begin early in school as part of the ongoing education of students. This proactive approach to transition can be considered transition education (Clark & Kolstoe, 1995).

It is important to recognize that the process whereby students are taught the knowledge and skills, as well as connected to the supports and services that they will need later on, is a shared responsibility. Whereas the school should take the lead in this effort, the family, the student, and other service providers also play critical roles. Depending on where a student lives, other providers may not exist or may not contribute substantially to this transition process. When this is the case, school-based personnel will likely need to play a larger role.

2. Basic concepts of transition services

In the United States, transition services for special needs students became a mandate in federal level special education law in 1990. This law, known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), required transition services for students with special needs when they attained the age of 16. This meant that an array of services would be initiated during the last years of secondary education. It should be pointed out, however, that transition services were being developed and implemented in many parts of the country during the mid to late 1980s.

2.1 Rationale for implementing transition services

A number of reasons can be identified to explain why transition services became a required component of the special education process in the United States. One of the most compelling reasons that led to the requirement of transition services was the data about the adult outcomes of many former special needs students. Research that had been conducted as part of a number of different follow-up studies substantiated a rather bleak picture of unemployment/underemployment, few individuals living independently, limited social lives, and little community involvement. In addition to the adult outcome data, information related to graduation rates indicating high dropout rates contributed to the movement to better prepare students for life after secondary school.

2.2 Definition of transition services and implications for practice

The current version of the law, which was most recently reauthorized in 2004, defines "transition services" as:

a coordinated set of activities for a child with a disability that is designed within a results-oriented process that is focused on improving the academic and functional achievement of a child with a disability to facilitate movement from school to post-school activities including postsecondary education, vocational training, integrated employment, continuing adult education, adult service, independent living, or community participation (§300.42(a)(1)).

This definition clearly conveys the fundamental goal of providing activities in school prior to students’ graduation or completion of school. However, the definition is somewhat broad and does not provide the level of comprehensiveness that is needed to ensure that transition services have the most effect on future success.

The definition that has been developed and proposed by the Division on Career Education and Transition of the Council for Exceptional Children provides a more elaborate description of the meaning of transition. Even though this definition was developed a number of years ago, it still remains relevant and useful for guiding work in this area. The definition reads as follows:

Transition refers to a change in status from behaving primarily as a student to assuming emergent adult roles in the community. These roles include employment, participating in post-secondary education, maintaining a home, becoming appropriately involved in the community, and experiencing satisfactory personal and social relationships. The process of enhancing transition involves the participation and coordination of school programs, adult agency services, and natural supports within the community. The foundations for transition should be laid during the elementary and middle school years, guided by the broad concept of career development. Transition planning should begin no later than age 14, and students should be encouraged, to the full extent of their capabilities, to assume a maximum amount of responsibility for such planning. (Halpern, 1994, p. 117)

2.3 Major domains of transition

Although the actual transition domains used in various regions in the United States vary, a number of key areas for which transition assessment and planning should be conducted can be identified. Table 1, based on the domains used in the Transition Planning Inventory (2nd edition), lists 11 transition domains. The scope of these domains shows the type of comprehensiveness that should be used when providing transition planning and services. The table also provides a few examples of what each domain covers. It is important to note that most special needs students do not have problems in all of the domains; they often only have transition needs in some of the areas. Nevertheless, all areas should be examined for transition needs, as well as identifying transition strengths, as part of the process.

2.4 Guiding principles of transition

Certain principles are essential to guiding the transition process for special needs students. Patton and Dunn (1998) identified a number of guiding principles that serve as a frame of reference for the implementation of transition services. These principles have come from the professional literature on transition and from actual practice and are listed below:

— Transition efforts should start early;

— Planning must be comprehensive;

— Planning process must balance what is ideal with what is possible;

— Student participation is essential;

— Family involvement is crucial;

— The transition planning process must be sensitive to family values and cultural diversity;

— The identification of supports and services is extremely important;

— Community-based experiences and other activities are extremely helpful in establishing needed transition skills;

— Having sufficient time to conduct a transition assessment, planning, and instruction is crucial;

— The transition planning process should include a focus on the student's strengths as well as his or her needs;

— Ranking of transition needs might be necessary;

— Transition planning is beneficial for all students (Patton & Dunn, 1998, pp. 16-18).

3. What the literature informs us about transition services

In the past two decades, transition-related interventions have evolved from theoretical- and empirically-based analyses into a multidimensional service program for individuals with disabilities. To review the trends and patterns of research studies on effective transition-related interventions, the literature is organized by the research-based taxonomy developed by Kohler and Field (2003). Kohler developed a taxonomy of transition interventions (Kohler, 1996, 1998; Kohler & Field, 2003); this taxonomy posits five sets of school-related services to be delivered in secondary settings to enhance the transition of post-school outcomes: (a) student-focused planning, (b) student development, (c) interagency and interdisciplinary planning, (d) family involvement, and (e) program structure.

Based on the transition intervention framework suggested by Kohler and Field (2003), Cobb and Alwell (2009) reviewed the relationship between interventions for transition planning/coordinating and the transition outcomes for secondary-aged youth with disabilities using a total of 31 studies. Results indicated that the (a) student-focused planning (e.g., student involvement in transition planning, student involvement in transition-related activities, or self-directed instruction of individualized education program (IEP)) and (b) student-development (e.g., work awareness curriculum and instruction, vocational training and transition planning program, career education instruction) interventions have shown to be promising in improving the transition outcomes of youth with disabilities.

Therefore, the (a) student-focused planning and (b) student-development appeared to be important predictors that improve post-school outcomes in three post-school outcome areas (i.e., education, employment, independent living). Regarding the three outcome areas, Test et al. (2009) conducted a review of the secondary transition correlational literature to examine in-school predictors to post-school outcomes for students with disabilities. Based on the review, they identified 16 in-school predictors of post-school outcomes. Of the 16 predictor categories, the factors related to (a) student-focused planning and (b) student-development were included in four predictors (i.e., paid employment/work experience, self-care/independent living skills, student support, inclusion in general education) that improved post-school outcomes in all three areas (i.e., education, employment, independent living). Additionally, seven factors (i.e., career awareness, interagency collaboration, occupational courses, self-advocacy/self-determination, social skills, transition program, vocational education) improved outcomes for two areas (i.e., post-school education and employment); remaining five predictors (i.e., community experiences, exit exam requirements/high school diploma status, parental involvement, program of study, work study) improved post-school outcomes for only one area (i.e., employment).

4. How to conceptualize the transition planning process

4.1 Student-focused planning

Regarding student-focused planning suggested by Kohler and Field (2003), Richter and Mazzotti (2011) reviewed 16 articles related to Summary of Performance (SOP) to promote transition-related outcomes given the federal mandates indicating that the SOP is to provide the child with a summary of the academic achievement and functional performance to assist in meeting postsecondary goals (IDEA, 2004, section 614 (c)5ii). The majority of articles (62.5%) were related to developing SOP documents in a way to promote transition to adult life broadly (rather than a solely focus one adult outcome area). From their review, they found some common suggestions for the development of the SOP such as (a) student involvement, (b) use of template, and (c) inclusion of comprehensive student information driven by age-appropriate transition assessments.

Griffin (2011) further examined the student participation in planning and reviewed 17 intervention studies on student IEP participation among high school students with disabilities, focusing on the inclusion and performance of culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) students. The positive effects of interventions and positive results for CLD participants were found on student IEP participation by teaching students with various disabilities how to actively participate in IEP meetings. Many interventions included commonly used intervention components such as direct instruction, modeling, verbal rehearsal, and role-playing.

4.2 Student development

Regarding student development, Storey (2007) reviewed 14 empirical studies related to self-management strategies in supported employment settings for individuals with disabilities that include a variety of techniques such as the use of picture cues, self-recording, self-monitoring, self-recruited feedback, self-reinforcement, auditory prompts, and self-evaluation. The strategies were used separately or in conjunction with other approaches/ /strategies such as systematic instruction, and job coach supports.

The review by Landmark, Ju, and Zhang (2010), however, revealed that two categories (i.e., work experience and preparation for employment) related to student-development were the most and the second most substantiated practice among 29 studies on transition outcomes or practices for individuals with disabilities. As a result of their review with a purpose of examining empirically substantiated best practices in transition, they identified eight transition-related practices, from most to least substantiated, based on the number of studies that supported each practice were (a) work experience (i.e., having a job during high school), (b) preparation for employment (i.e., vocational and employment trainings), (c) family involvement, (d) general education inclusion, (e) social skills training, (f) daily living skills training, (g) self-determination skills training, and (h) community or agency collaboration.

4.3. Transition planning process

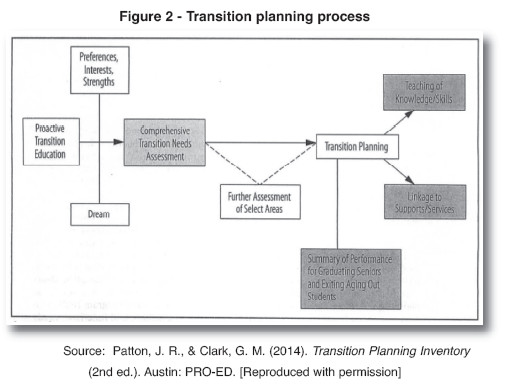

A model of transition assessment and planning is introduced in this section. The model, shown in Figure 2, was originally developed by Patton and Dunn (1998) and revised by Patton and Clark (2014). This model emphasized the fact that the transition planning process is a multicomponent process. The process begins in the early years of school and continues up until the time when a student graduates or leaves school. We feel that each component of the model is essential for ensuring that a comprehensive transition process is provided to students. The following description provides an understanding of the various components of the model.

Proactive transition education. This component refers to any activity that typically occurs in the early levels of schooling that relate to later adult outcomes. This phase includes the beginning stages talking about real life topics and includes the first stage of the career education process.

Dream. This component of the model suggests that students should have opportunities to "dream" about their future. It is extremely important for students to have the chance to think broadly about what they want to do in the future and where they want to do it. An important point, however, is that we must provide these opportunities early enough so that students have an opportunity to recognize whether their dreams are realistic or not.

Determination of preferences, interests, and strengths. As a beginning step in the "formal" transition planning process, we need to develop ways to identify the preferences and interests of students in regard to careers and other life-related areas. As noted previously, we should consider a student’s strengths, and, as a result, we need to have tools for identifying the strengths. Instruments like the Career Interests, Preferences, and Strengths Inventory (CIPSI) (Clark, Synatschk, Patton, & Steel, 2012) offer efficient and effective ways to accomplish this goal. The CIPSI is a computer (soon to be web-based) instrument that is made up of four individual’s inventories: personal interests survey; strengths survey; general preferences survey; and careers survey. The instrument provides students with "four exploration experiences for… students beginning the career planning process" (Clark et al., 2012, p. 4) and relates the results from these experiences to Career Clusters areas. This process leads to more detailed career exploration activities.

Comprehensive transition needs assessment. As the centerpiece, so to speak, of this process is the determination of the transition needs that a student has. It is very important to do this early in the process so that there is sufficient time for knowledge and skills that a person develops transition plans and to provide instruction and establish linkage activities when needed. An important point that needs to be understood about this component of the process is that, whatever tools are used to determine needs, these tools need to be comprehensive so that all of the areas of transition are considered.

Further assessment of selected areas. Often there is a need to obtain more detailed information about certain transition domains. When this is necessary, we need to have an array of additional formal, but mostly informal, assessment tools related to the specific transition domains available to be able to establish more in depth information about certain areas when needed. The resources that provide additional assessment tools include: Informal Assessments for Transition: Employment and Career Planning (Synatschk, Clark, Patton, & Copeland, 2007); Informal Assessments for Transition: Postsecondary Education and Training (Sitlington, Clark, & Patton, 2008); and Informal Assessments for Transition: Independent Living and Community Participation (Synatschk, Clark, & Patton, 2008).

Transition planning. Upon completion of the assessment phase, actual transition planning should commence. As noted in the model, two forms of planning can and should be considered: instructional goals that are associated with the "teaching of knowledge/skills" and linkage goals that are associated with "linkage to support/services". Instructional goals relate to the knowledge and skills associated with transition skill areas that still need development. Linkage goals refer to the connections that need to be made to those supports and services that will be needed in the future.

Summary of performance. The United States federal law also mandates that a summary of the student’s academic achievement and functional performance, along with recommendations on how to help the student in meeting their post-school goals, be developed prior to the student’s leaving school. As Patton, Clark, and Trainor (2009) suggest, "the summary of performance provision is focused on providing the student, as well as his or her family, with information that will be useful in the future across a range of settings" (p. 5).

It is our belief that this model can serve as a framework for schools to provide a powerful and effective program for addressing the transition strengths and needs of students who will be leaving school and entering a new world of challenges.

Final comments

The transition planning process involves many different phases, as shown in Figure 2 and discussed in this article. It is our thinking that schools, families, and students themselves can contribute to this process to make it successful. The following lists summarize the key points that we feel are important ones to consider when conducting a comprehensive transition planning process.

How schools can best prepare students for life after high school:

— Teach important life skills within the curriculum;

— Develop self-determination/ self-advocacy skills;

— Assess and plan comprehensively for transition needs;

— Provide instruction in relation to knowledge and skills needed for adult living;

— Provide community-based experiences when possible.

How families can assist in the successful transition to adulthood:

— Become informed about the demands of adulthood and the transition planning process;

— Participate in the transition planning process;

— Seek assistance when needed;

— Advocate for their children.

How students can contribute to the transition effort:

— Identify their own preferences and interests;

— Understand their strengths and their challenges;

— Get involved as a contributing member in the transition process;

— Know where and how to access supports and services.

If the process specified in this paper is implemented as described, the outcome is an increased probability that a student, and his or her family, will be better prepared to deal with the demands of adulthood that the young adult will face upon leaving school. In the United States, the transition assessment and planning process is typically documented in the student’s IEP. However, the long-term impact of effective transition planning is reflected in successful adult outcomes for those students who benefit from systematic preparation for life after secondary school.

References

Clark, G. M., & Kolstoe, O. P. (1995). Career development and transition education for adolescents with disabilities (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Clark, G. M., Synatschk, K., Patton, J. R., & Steel, E. (2012). Career interests, preferences, strengths inventory. Austin: PRO-ED. [ Links ]

Cobb, B., & Alwell, M. (2009). Transition planning/coordinating interventions for youth with disabilities: A systematic review. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 32(2), 70-81. [ Links ]

Cronin, M. E., Patton, J. R., & Wood, S. J. (2007). Life skills instruction. Austin: PRO-ED. [ Links ]

Griffin, M. M. (2011). Promoting IEP participation: Effects of interventions, considerations for CLD students. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 34, 153-164. [ Links ]

Halpern, A. (1994). The transition of youth with disabilities to adult life: A position statement of the Division on Career Development and Transition, The Council for Exceptional Children. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 17, 115-124. [ Links ]

Halpern, A. S. (1993). Quality of life as a conceptual framework for evaluating transition outcomes. Exceptional Children, 59, 486-498. [ Links ]

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA), 20 U.S.C. § 600 et seq. (2004).

Kohler, P. D. (1996). Taxonomy for transition programming: Linking research and practice. Champaign, Illinois: Transition Research Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign.

Kohler, P. D. (1998). Implementing a transition perspective of education: A comprehensive approach to planning and delivering secondary education and transition services. In F. R. Rusch & J. G. Chadsey (Eds.), Beyond high school: Transition from school to work (pp. 179-205). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Kohler, P., & Field, S. (2003). Transition-focused education: Foundation for the future. Journal of Special Education, 37(3), 174-184. [ Links ]

Landmark, L. J., Ju, S., & Zhang, D. (2010). Substantiated best practices in transition: Fifteen plus years later. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 33(3), 165-176. doi:10.1177/0885728810376410 [ Links ]

Patton, J. R., & Clark, G. M. (2014). Transition Planning Inventory (2nd ed.). Austin: PRO-ED. [ Links ]

Patton, J. R., & Dunn, C. (1998). Transition from school to young adulthood: Basic concepts and recommended practices. Austin: PRO-ED. [ Links ]

Patton, J. R., Clark, G. M., & Trainor, A. (2009). Summary of performance system. Austin: PRO-ED. [ Links ]

Price, L., & Patton, J. R. (2003). A new world order: Connecting adult developmental theory to learning disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 24, 328-338. [ Links ]

Richter, S. M., & Mazzotti, V. L. (2011). A comprehensive review of the literature on summary of performance. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 34, 176-186. doi: 10.1177/088572881139 [ Links ]

Sitlington, P. L., Clark, G. M., & Patton, J. R. (2008). Informal assessments for transition: Postsecondary education and training. Austin: PRO-ED. [ Links ]

Storey, K. (2007). Review of research on self-management interventions in supported employment settings for employees with disabilities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 30, 27-34. [ Links ]

Synatschk, K. O., Clark, G. M., & Patton, J. R. (2008). Informal assessments for transition: Independent living and community participation. Austin: PRO-ED. [ Links ]

Synatschk, K. O., Clark, G. M., Patton, J. R., & Copeland, L. R. (2007). Informal assessments for transition: Employment and career planning. Austin: PRO-ED. [ Links ]

Test, D. W., Mazzotti, V. L., Mustian, A. L., Fowler, C. H., Kortering, L., & Kohler, P. (2009). Evidence-based secondary transition predictors for improving postschool outcomes for students with disabilities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 32(3), 160-181. [ Links ]

Wandry, D., Wehmeyer, M., & Glor-Scheib, S. (2013). Life-centered education: The teacher’s guide. Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children.

Recebido em fevereiro/2016

Aceite para publicação em abril/2016