1. Introduction

Rapid expansion in higher education is not a new phenomenon, having occurred since the 20th century, nor is it geographically localized, having been observed worldwide. In 1900, almost 500,000 people on the planet were enrolled in higher education institutions, while in 2000 this number was approximately 100 million (Schofer & Meyer, 2005). By 2016, the estimate had increased to almost 216 million (Calderon, 2018). This growth has been associated with a change in societal models, with ample democratization catalyzing education as a way to generate improved social mobility (Schofer & Meyer, 2005; Schwartzman, 2015). Indeed, young adults having graduated from higher education have, on average, a 40% higher income than those who have completed only secondary education (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2019).

At the end of the 20th century, the demand for access to higher education was also stimulated by UNESCO, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (Neves, 2018). These institutions advocated systemic reforms that would respond to this growing demand by diversifying post-secondary education models, permitting private institutions’ participation in higher education and offering distance education (Segenreich & Castro, 2012). Underlying these recommendations was the premise that the public authorities of countries undergoing development would not have the conditions to assume the entire cost of the expansion of higher education within their classical model, which features public teaching and research institutions with face-to-face offerings. Alternatively, these suggestions, offered as a solution to concerns about increasing access to higher education, have been associated with neoliberal ideology, namely its commitment to the market economy with a reduction in the size of the State and the idea of promoting freedom of choice for individuals (Olssen & Peters, 2005). The opening of the higher education sphere to private institutions and for the growing use of technology can be framed as a response to the interests of capital, in search of new areas to be explored, configuring an enormous educational market with global dimensions (Lima, 2011b).

Distance education appears as one of the ingredients in this boilerplate recipe, one which has somewhat changed from its initial motivations. Originally conceived of as an instrument to reach individuals who lived far from developed centers or who had not completed their education in the customary timeframe (Mill et al., 2008), international entities now promote it as a solution directed at a population with fewer resources, even in large centers (Segenreich & Castro, 2012; Segrera, 2016). The institutions which are able to offer education on a large scale at lower cost tend to stray from the classical university model of producing knowledge, generating legitimate concerns regarding the quality of education offered (Altbach, 2008). It is also important to note that the adoption of distance education has been more commonplace in emerging countries than in developed ones (Costa, 2016).

In choosing Latin America as the focus, similarities are observed with regard to the various reforms that different countries have experienced since the ‘90s (Bernasconi & Celis, 2017; Segrera, 2016): expansion, diversification, and privatization have been common policies, for those pursuing a neoliberal agenda. For example, during a short period from 1995-2002, in Latin America and the Caribbean, the number of private institutions increased from 53.7% to 69.2% (Segrera, 2016). With reference to student numbers, Latin America is renowned as the global region with the highest percentage of enrollment in private institutions (OECD, 2015), the product of a process of commercialization that is not always concerned with the quality of the education offered (Brunner, 2013). The similarities found in the higher education scenario in Latin America cannot, however, overshadow the differences between these countries, which, for reasons of political, economic, or social order, have not adopted with the same swiftness or intensity the policies proposed by international organisms (Alcántara et al., 2013).

Accordingly, one of the aspects that has become important to examine involves questioning how distance education has been incorporated into higher education policies in South American countries and what the causes behind the verified similarities and divergences could be. The objective of this study is to compare the reality of four South American countries regarding the recent evolution of distance education participation in higher education. Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Colombia were the four countries chosen based upon the greatest availability of official data on distance education evolution from 2010 to 2018.

Below, this paper presents the methodology used. Then, it offers a panoramic view of this expansion in each country, followed by an analytical synthesis where the convergences and divergences are identified, as well as their possible causes. The article concludes with the presentation of the final considerations.

2. Methodology

This study involves the analysis of official data, legislation, and research regarding the most recent evolution of distance education in higher education (particularly since 2010) in the four countries studied: Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Colombia. The data is part of a larger study on the recent evolution of distance education in higher education in Latin America. For this article, the data presented and analyzed refer to the four countries with the highest availability of official statistical information. Data on enrollment numbers in higher education, with a distinction made between traditional and distance learning courses, were obtained from reports published by public agencies responsible for education statistics in each country: Ministerio de Educación (Argentina); Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira – INEP (Brazil); Ministerio de Educación – Mineduc (Chile); Ministerio de Educación Nacional (Colombia). In the case of Colombia, part of the necessary data was not available on the official website and was obtained by contacting the responsible authorities by e-mail. Government statistical data were analyzed with the aim of verifying the evolution of the number of enrollments in higher education, making a distinction between data from distance and traditional education.

With data from enrollments, it was possible to quantify the growth rate of the two types of education in each country, allowing comparisons to be made between the four countries studied. However, as the data collected from each country does not cover exactly the same period, it was not possible, as originally intended, to compare data from the four countries over each of the past 10 years. In any case, the information available has already served the purpose of revealing some significant similarities and differences.

In addition to the official enrollment data, the study examined the legislation in each country regarding higher education. These laws were collected on the websites of official government agencies. Altogether, 11 documents from the four countries studied were analyzed, all of which were found in the respective country’s legislative document repositories. The analysis of this set of documents sought two objectives: first, to verify the degree of autonomy of universities in offering distance courses; and second, to examine whether for-profit institutions can operate in this market. The exploration of documents followed the procedures of content analysis (Bardin, 2016), seeking relevant information to answer the two fundamental questions of this stage of the research.

The other important set of sources consisted of 81 articles published until 2019 that discuss the recent expansion of higher education in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Colombia. The articles were found in the EBSCO, CAPES and SciELO databases. The criteria for selecting articles from these databases were: publication in the last 10 years; presence of analysis of the evolution of higher education in each country individually, or in a subset of the countries studied. The analysis of these articles focused on aspects that could help to explain each country’s trajectory regarding the evolution of distance education in academia, considering aspects such as the existence of political disputes regarding public policies, the type of regulation adopted, and the comparison between traditional and distance learning in terms of quality.

Based on the analysis of this dataset, an analytical narrative of the recent evolution of higher education in each country was developed. Then, we sought to identify similarities and differences between the trajectories of the four countries, as well as to propose possible explanations for the convergences and divergences, based on the institutional scenario that influences the functioning of higher education in these four countries.

3. Argentina

In Argentina, higher education began to take on increased importance in educational policies as of the 1980s, when the restoration of democracy opened up space for university institutions while, at the same time, new social expectations were generated around them. Currently, higher education in Argentina is made up of public, private and foreign institutions, the latter category having low representation. There was a 39% spike in the number of institutions in a period of 12 years (2003 to 2015), increasing from 95 to 132. With respect to the administrative category, the distribution between public and private management is equally balanced: in 2017, 50% of higher education institutions (HEI) were public and 48% private, with only 2% foreign (República Argentina, 2018).

Even though the distribution between public and private institutions is uniform, the Argentinean history of higher education is punctuated by the predominance of public administration, not only because of a preference for public education on the behalf of Argentinean university students, but also because of the preference of employers in the private sector to recruit graduates from public institutions (Moreira, 2013, p. 62). The role of public education is also evidenced when one considers enrollment numbers: in 2017, public institutions accounted for 79% of all enrollments (República Argentina, 2018).

In Argentina, public authority exercises control over HEI, both public and private. Argentinean legislation requires that both private and public institutions must be not-for-profit, demanding that establishments to be incorporated as a civil society or foundation. The Argentinean Ministry of Education has registered two types of education models for higher education: face-to-face and distance. In the official database used in this investigation, information relating to higher education began to present data according to the teaching methodology, face-to-face or distance, in 2015. In that year, there was less than 7% enrollment in higher education distance programs. Later, in 2017, the enrollment percentage of that modality increased to 8% (República Argentina, 2018).

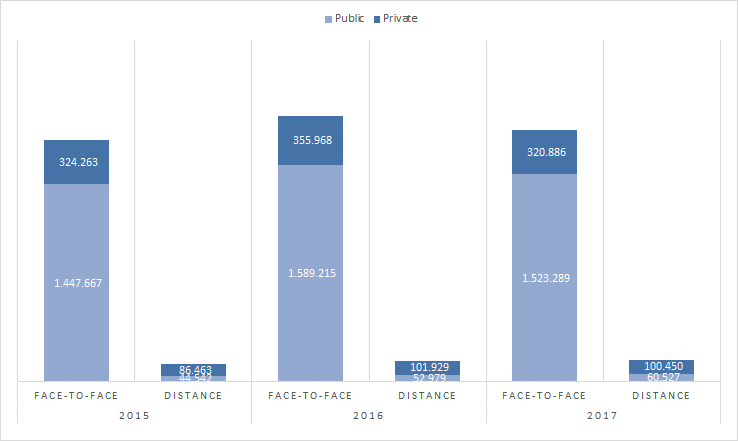

The analysis of enrollment based upon modality and administrative category revealed that with private institutions, to the contrary of what was observed with face-to-face education, more enrollments occurred in distance modalities, as illustrated in Graph 1.

Source: Organized by the authors based on the República Argentina (2016, 2017, 2018).

Graph 1: The Evolution of Enrollments Based on Modality and Administrative Category in Argentina 2015 – 2017.

Observing the data from 2017, it was found that, with respect to the face-to-face modality, public institutions held 82.6% of enrollments whereas the distance modality captured only 37.6%. However, regarding the distance modality, enrollments grew constantly, as public institutions also began to demonstrate performance gains in this model.

Despite this raw growth, there still remains a worry. According to the OECD (2015), virtual distance education programs in Argentina are lacking in quality. One of the main causes is that this type of education has not always expanded via the introduction of new teaching methods and practices, as it has been frequently used as an opportunity to increase revenue (private universities) or funding (public universities). There also exists the perception that this form of teaching does not require institutional investment, such that it has been branded a low-cost system (OECD, 2015).

In terms of higher education quality in Argentina, the National Commission on University Evaluation and Accreditation, CONEAU, has developed institutional activities in national and private universities, considering various attributions, namely: institutional evaluation, career accreditation and operating authorization. These procedures are employed to guarantee quality in Argentinean higher education and have as an aim the recommendation of improvements in HEI, through an institutional evaluation that should occur in a participatory manner on a regular basis, taking into consideration both quantitative and qualitative aspects. The evaluation must respect the institutional project, prioritizing the university’s autonomy; thus, to accomplish this, the evaluation is conducted by each institution or program’s own self-evaluation in tandem with an external evaluation by CONEAU (Oliveira, 2009).

In conclusion, Argentina’s higher education is predominately provided by public institutions with face-to-face enrollments constituting a vast majority. Regarding the issues of quality and evasion, Argentina still needs to improve the control and registry of statistical information to find ways to discourage dropouts and improve the quality of higher education. With respect to the distance education [DE] modality, the admission of students into HEI is growing at a moderate pace, superior to face-to-face growth, presenting itself as a solution for students seeking access to higher education.

4. Brazil

Higher education in Brazil has undergone major changes over the past 60 years, especially in the past two decades. In 1964, the enrollment rate was only 1.5% of young Brazilians from the ages of 15 to 19 (Barros, 2007, p. 13). In 1991, “the enrollment rate of young people from the ages of 18 to 24 increased to 8.0%” (Gomes & Moraes, 2012, p. 179). However, it was over the next couple of years that an accentuated enrollment increase occurred, as a result of a federal policy that undertook a transition from a system for the elite to a system for the population at large (Gomes & Moraes, 2012). Between 1995 and 2010, according to Mancebo et al. (2015), “an increase in the total number of enrollments in the order of 262% occurred” (p. 35). This expansion was much more common “in private institutions (347%) than in public institutions (135%)” (Mancebo et al., 2015, p. 35). Gradually, as a result of a regulation that permitted for-profit companies to offer higher education programs, and because of limited government spending on public institutions, Brazilian higher education became more and more privatized. In 2018, of the 2,537 existing institutions of higher education in Brazil, 88.2% were private and accounted for 75.4% of the total enrollment in undergraduate programs (Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira [INEP], 2019). Because the majority of enrollments are in for-profit institutions (Carvalho, 2013), the Brazilian context differs greatly from that observed in other countries. In the US, for example, for-profit higher education institutions represented 9.5% of enrollments in 2010, but participation lowered to a mere 5.0% in 2017 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2018).

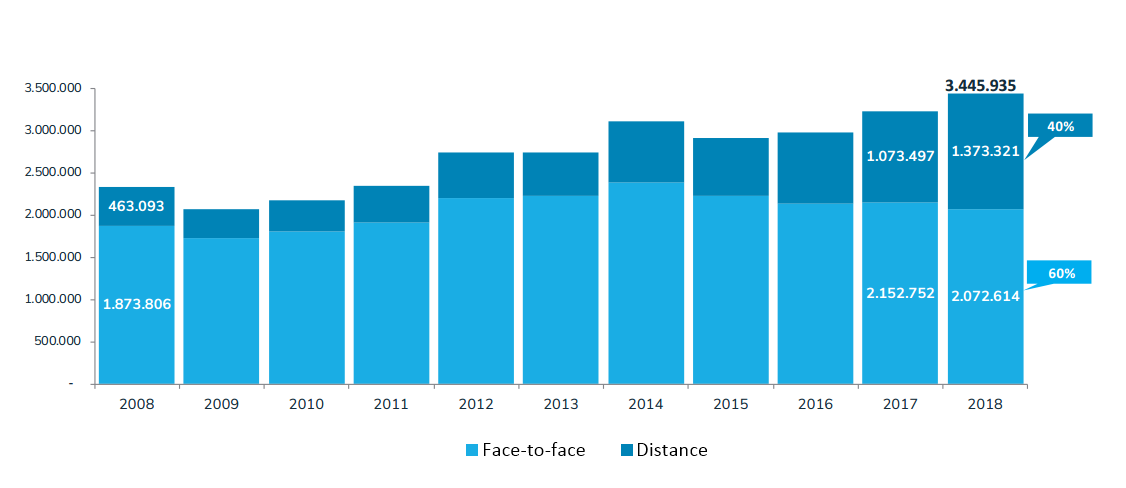

Starting in the beginning of the 21st century in Brazil, there has been a gradual concentration in private institutions, with some becoming attracting national and international private investment (Costa, 2016) and becoming powerful enough to lobby the National Congress and Ministry of Education to obtain favorable regulatory changes (Schwartzman, 2015). Distance education became more prevalent in this context of the commodification of Brazilian higher education. In 2000, “only 0.06% of university students were enrolled in distance programs” (Mancebo et al. 2015, p. 39). By 2018, this number had grown to 24.3% (INEP, 2019). In Graph 2, the rapid growth of distance education in Brazil can be confirmed based upon its number of new enrollments in relation to the total number of enrollments in face-to-face undergraduate programs. In 2018, 40% of all new students at the undergraduate level were enrolled in distance programs.

Source: Adapted from INEP (2019).

Graph 2: Admission Numbers in Undergraduate Programs According to the Teaching Modality – Brazil – 2008-2018.

Conceived to promote the democratization of access to higher education, distance education became a strategy applied more and more by large private higher education companies that viewed this modality as a means to leverage their profits with low cost offerings on a large scale. As a result, in 2018, private higher education institutions accounted for 91.6% of the total enrollments in distance education, as shown in Graph 3 (INEP, 2019).

The rapid growth observed in enrollments in private institutions’ distance programs, specifically starting in 2016, can be attributed to a loosening of rules regulating the DE courses and also to a reduction in federal spending on higher education (Endo & Farias, 2019). In its national education plans, Brazil has sought to rapidly increase higher education enrollment. For example, in the National Education Plan put forward for the period 2001-2010, distance education was referenced as a strategy to allow for this expansion. Likewise, the National Education Plan for 2014-2024 established, as one of its aims, a target net rate for higher education enrollment of 33% for the population between 18 and 24 years old; however, it did not explicitly reference distance education as a way to achieve this objective (Haas et al., 2019). The DE incentive was subsequently advanced through a significant shift in legislation regarding this teaching modality. Responding to private institutions’ demands in 2017, the Brazilian government loosened regulations for the creation of distance education programs. This set of measures has been the main factor behind the fast growth of DE since 2017 (Haas et al., 2019).

Several studies have demonstrated that the Brazilian education policy, with respect to distance education in higher education, has followed the formula promoted by the World Bank, OECD and UNESCO (Schwartzman, 2015; Segenreich & Castro, 2012). For Segenreich and Castro (2012), UNESCO’s understanding is that governments, to be able to respond to the current demand for higher education,

need to adopt new models of university programs and permit the opening of more undergraduate places, mostly in private institutions and through the use of the DE modality to facilitate service to a larger public without having professors and students in the same physical location. (p. 93)

This flexibility provided by DE permits the reduction of educational financial costs while more than adequately attending to the population in need of this level of education.

However, this rapid expansion of distance education in Brazil is interpreted by some researchers as the result of a policy that responds less to the public interest than to international capital’s pressure “in search of new exploration domains” (Lima, 2011a, p. 20). Following this line of interpretation, Ventura and Cruz (2019) understand that Brazil’s adoption of distance education is “inserted in a game of forces that dispute the arena of economic control over contemporary education, a new frontier for investment in Brazil and worldwide” (p. 253).

The international institutions that have encouraged the adoption of distance education and the privatization of higher education in developing countries, such as the OECD (2015), warn that these measures must be accompanied by policies that guarantee the quality of distance courses. Brazil has adopted an exam with the objective of evaluating the student performance of those who have concluded their undergraduate program. It is referred to as the National Student Performance Exam (ENADE). One comparative study of ENADE results revealed that, when comparing face-to-face with distance education, students from distance programs, on average, had lower performance than their colleagues in face-to-face programs (Bielschowsky, 2018).

In conclusion, Brazil is a country where distance education and the privatization of higher education are articulated strategies. In maintaining the trend observed over the last years, Brazil will soon place most of its undergraduates in distance programs offered by private institutions. While this perspective contributes to a greater number of Brazilians accessing higher education, there is a legitimate concern regarding the quality of this education, and, consequently, the effectiveness of the educational policy adopted in the last 20 years.

5. Chile

The incorporation of ICTs in the Chilean higher educational sphere began in 2000, a period in which the use of digital tools as teaching aids expanded, with a limited percentage of content in courses provided for online and generally related to administrative aspects of the practice of teaching. Distance education in the country was understood, during this period, principally as a mechanism complementary to face-to-face teaching (e-support).

The Chilean Ministry of Education’s Directorate uses three categories: state universities, subsidized private universities, and private universities ( Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2019). State universities are higher education establishments with academic and administrative autonomy that are financed by the State (Ley n.º 21.094, de 5 de junio de 2018). Subsidized private universities receive various State contributions, with an annual fixed rate in the national budget. Private universities are private establishments as such, with administration and financing by individuals. These institutions cannot be for-profit; only the Technical Formation Centers and the Professional Institutes can be, as determined by the 20.845/2015 Law (Ley n.° 20.845, de 8 de junio de 2015 de Ministerio de Educación de Chile).

Since 2010, there has been an increase in Chilean university enrollment, with the subsector of distance education in HEI growing the most. This enrollment modality has increased significantly as of 2013, reaching approximately 35,409 students in 2018. Over those four years, the number of distance education programs increased from 140 to 353, with a concentration of more than 80% of enrollments in four institutions, according to the HEI Informational System’s Historical Database (SIES) (Martinez, 2019).

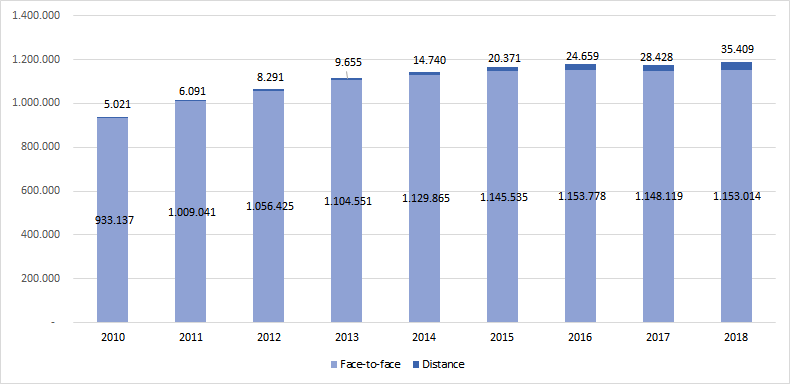

In 2018, the total number of enrollments reached 1,158,014 students, including bachelor, post-graduate, and post-degree, which represents a 41.6% increase over the period from 2009 to 2018 (Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2018), which can be observed in Graph 3:

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data obtained from the Ministerio de Educación de Chile (2018).

Graph 3: HE Enrollment and DE Participation.

The high growth in enrollments in higher education can be explained due to the following background information: a) the creation and implementation of the State Guarantee Credit (CAE) in 2006, which facilitated enrollment growth in private universities and professional institutes; b) the growth in face-to-face undergraduate programs, based upon the admission of low-income students; and c) an increased exigency from the labor market with regard to professionals’ competencies and abilities (Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2016).

Since 2006, Chile has adopted the Higher Education Quality Guarantee National System. However, this system does not have specific criteria to accredit distance programs, which leads to the fact that very few distance education programs opt to be voluntarily accredited (González & Espinoza, 2011).

With a population of nearly 17 million people, according to the data provided by the Ministry of Education in 2018, almost 1,153,000 students are in tertiary education in Chile. Of this figure, about 35,500 students were in undergraduate distance programs. This number continues to increase; however, it is far from being significant in relation to the total number of students enrolled in undergraduate programs, even though it increased by 140.7% in the period from 2014 to 2018.

Based upon the information presented, it can be noticed that distance education is still not viewed as an option by a large part of Chileans that have access to higher education. This has occurred largely because there do not exist specific regulatory policies that ensure quality in education. For Santander et al. (2011), “in Chile, distance higher education does not have specific norms that regulate this modality. Nevertheless, it has developed a varied offer, stimulated mainly by the massification of information technologies and the Internet” (pp. 67-68). This lack of regulation can explain why, despite its coverage and access, distance education has not been well received in some sectors (Cortés, 2016).

Moreover, it is important to point out that the Chilean higher education system has been constantly questioned since the explosion of criticism in 2011, when the student movement spontaneously organized, paralyzing various universities throughout the country. This publicized a series of problems regarding private universities’ indirect profits, high tuition and the fraud that existed in the Accreditation of Quality Graduate Program. In 2013, during the pre-election presidential campaign, the candidate Michelle Bachelet made an agreement with the students guaranteeing that, upon winning the elections, there would be a higher education structural transformation that included free and high-quality education for all. Yet the student movement’s scope and influence upon any transformations in higher education in Chile are difficult to predict over the long-term because of the political ups and downs and the concurrent changes to governments with differing interests.

6. Colombia

Colombia’s education system is divided into three basic types of higher education institutions, as follows: professional technical institutions, university and technology institutions, and universities. They are organized according to official administration, recognized as either public (national, states and municipalities) or private (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2017). Both types of administration are considered a public service with a guarantee of autonomy.

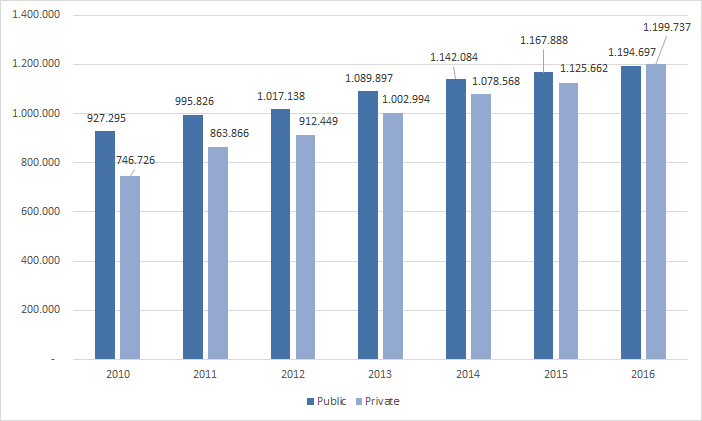

In 2010, the total number of enrollees in higher education courses was 1,674,021 students, increasing to 2,394,434 in 2016 (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2017). Graph 4 represents the evolution of the number of enrollments during the period from 2010 to 2016 in public and private higher education in Colombia. It is important to note that, according to this data, since 2010 the number of enrollments in private education has greatly increased. In 2016, private enrollment surpassed that of public higher education.

Source: Elaborated by the authors based upon the data from Colombia’s Ministry of National Education (2017).

Graph 4: Number of Enrollments in Higher Education in Colombia From 2010 to 2016.

Despite the strong presence of private institutions (all of them not-for-profit), it is important to delineate, in the Colombian higher education development process, the articulation of the student movement against the commodification and privatization of higher education, a reform proposal that was put forward by the presiding government of Juan Manuel Santos in 2011. The students’ actions in the struggle for public, autonomous, and high-quality education forced the government to backtrack on its proposal to finance higher education with private capital. In 2018, the student movement returned to the streets and, through negotiations with the national government, was able to achieve some of its objectives, including increased spending for higher education, in addition to the promise of guaranteed public education in the country (Freddy & Galindo, 2019).

Distance higher education in Colombia is divided between distance education and virtual education. Distance education appears in the social context as a solution to the problems of coverage and quality that are byproducts of serving a large number of students who could benefit from teaching, scientific and technical advancements that some institutions have achieved, principally due to inaccessibility, whether due to geographical location or the elevated costs of daily travel (Yong et al., 2017).

On the other hand, virtual education refers to the development of education programs that have, as their scenario of learning and teaching, cyberspace, without the necessity of face-to-face encounters between professor and student, but with the possibility of establishing an interpersonal relationship with an educational mentor. With this perspective, virtual education seeks to foster educational spaces, supported by ICT (information and communication technologies) to establish new forms of teaching and learning (Yong et al., 2017).

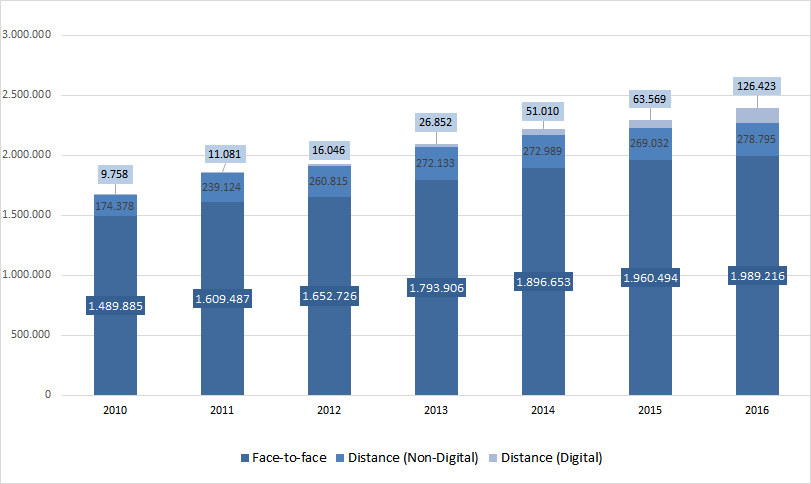

Graph 5 presents a demonstration of the evolution of the three modalities of higher education in Colombia during the period from 2010 to 2016:

Source: Elaborated by the authors based upon data from the Department of Colombian National Education (2017).

Graph 5: Enrollment Evolution in Colombian Higher Education

It is possible to note, in Graph 5, that virtual education, even though it was implemented more than three decades ago, still has limited participation in comparison to the numbers of face-to-face and traditional distance education. However, the very significant growth of virtual education that was registered in 2016 should draw attention, since enrollments doubled in comparison to the prior year.

The Colombian Ministry of Education created regulatory mechanisms to monitor the performance of diverse learning programs offered by higher education institutions. However, it is important to note that there are few studies on the student quality evaluation system of virtual education in higher education (Yong et al., 2017). This is a fundamental issue for further discussion on the teaching and learning processes of students of this teaching modality, as well as the resources used.

Finally, it is essential to emphasize that virtual education in Colombia, despite its accelerated growth from 2010 to 2016, still has low numbers in comparison with face-to-face and distance education. In the Colombian higher education system, despite governmental efforts to make the virtual modality more popular, face-to-face enrollment concentration greatly prevails.

7. Comparasion Of Trajectories

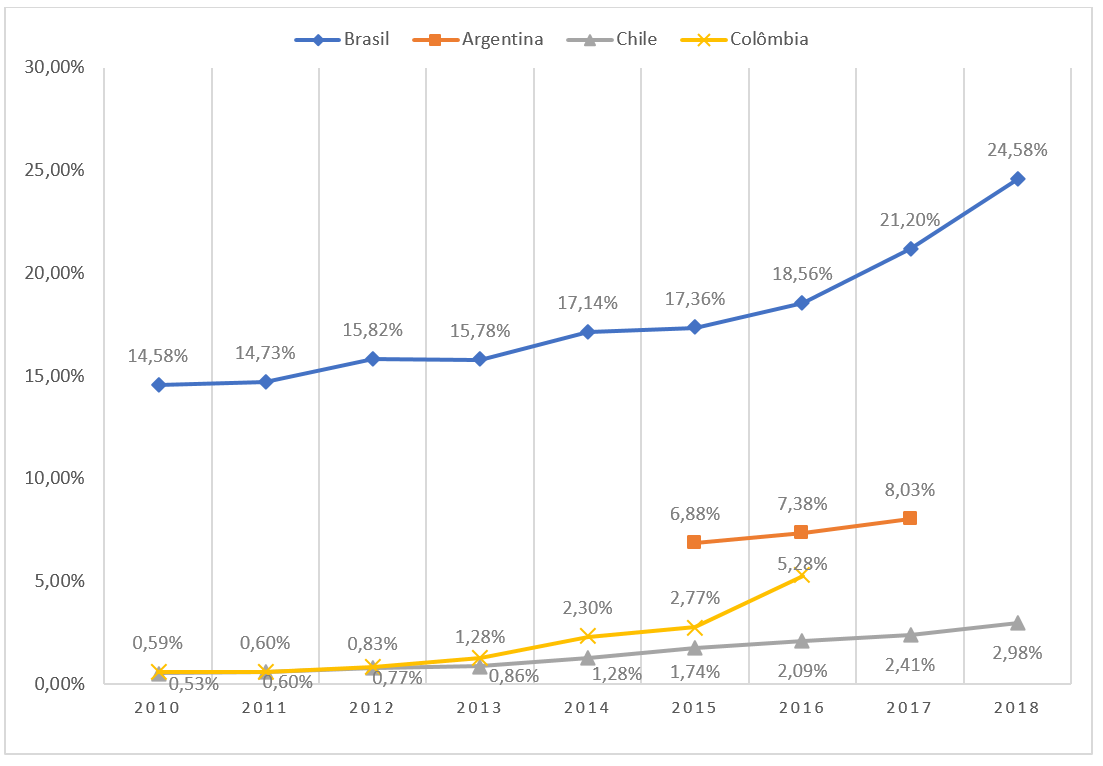

Through the collection of official data on enrollment in distance higher education, it was possible to find information on the four countries investigated: Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Colombia. With the aim of researching the evolution of the number of enrollments, it was our intention to study the data for a historical period of nine years, ranging from 2010 to 2018. For this entire period, data was only found in Brazil and Chile. In the case of Colombia, the data available only went as far as 2016. In the case of Argentina, the Ministry of Education only began collecting data on the analysis of enrollments according to teaching modality in 2015. The data obtained was analyzed and organized to calculate the percentages of enrollees, taking into consideration the distance methodology. In Graph 6, it is possible to observe the recent trends in distance higher education enrollment percentages for each country:

Source: Organized by the authors based upon official data provided by the Ministries of Education of each country.

Graph 6: The Percentage of Enrollment Evolution in Higher Education – Modality and Distance (2010 to 2018)Note: In the case of Colombia, only virtual distance program enrollment was taken into consideration.

Analyzed overall, it can be perceived that the four countries present an evolution in the distance modality of higher education. Furthermore, it is noticeable that Brazil, in addition to presenting the highest index, is also growing exponentially, particularly after 2016. It is seen that, in the Brazilian case, 91.6% of the enrollments in distance higher education are in private institutions (INEP, 2019), specifically those for-profit. The recent spike in distance higher education in Brazil is due to a set of factors, among which include the decrease in State control over the offer of distance programs, as of the sector’s new regulatory framework established in 2017, the gradual decrease in public spending in higher education and the existence of giant for-profit companies – with stock market shares – that have the resources to offer distance programs on a large scale with low tuition. The 10 largest private companies active in the Brazilian higher education sector were responsible, in 2018, for 2.6 million enrollees, which corresponds to 31.6% of the total (Endo & Farias, 2019).

As for Chile and Colombia, they started the decade of 2010 with very low percentages in distance program enrollments, hovering near 0.5% of the total, and practically developed in unison, maintaining similar percentages until 2013. Starting in 2014, Colombia presented superior growth to Chile’s, featuring a moderately increasing curve, which again expanded in 2016. The increase in DE program enrollment owes much to governmental policies that encouraged this teaching modality and the existence of a lengthy experience with open education in the country. Put together, traditional and virtual distance education constitute almost 17% of enrollments in higher education in Colombia in 2016.

On the other hand, the enrollments in distance higher education in Chile follow a pattern of consistent growth, slower than that of the other countries researched. The steadier rate in Chile can be explained by a set of reasons. In contrast to Brazil, which since 2002 has permitted for-profit private companies to act in this higher education sector, Chile only allows the participation of non-profit institutions. Additionally, there is evidence that in Chile there exists a tendency to belittle distance education, partly as a consequence of the absence of a process to guarantee the quality of the teaching offered, which inhibits the demand for this type of education (Cortés, 2016). Add to this, the systematic pressure exercised by the student movement, which has been antagonistic to the privatization of education and opposed the interests of private groups that could heavily invest in distance education.

In Argentina, distance education has been gaining traction as a teaching modality, mostly in private institutions that view distance education as an opportunity for growth. Although Argentina only presents data for a short time span, it has become clear that the DE modality is growing moderately. In the period used for this analysis, distance education grew at a more accelerated rate than face-to-face teaching: 23% in the period from 2015 to 2017 in contrast to only 4% face-to-face during the same period. In absolute numbers, distance education enrollments practically doubled in comparison to the total number of Argentinean higher education enrollments. Subsequently, in 2017, Argentina registered a decline of more than 4% in total enrollment in higher education, but the distance modality registered a growth of almost 4%. In other words, what is taking place in other countries in South America is also occurring in Argentina, with distance education accounting for an expanding part of higher education.

The comparison between trajectories in distance education growth in higher education in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Colombia reveals a significant difference between Brazil and the other countries. If the analysis were to look at only the participation of private institutions in higher education (regardless of whether they are for-profit or nonprofit), Brazil and Chile are very similar, but a great distance separates them regarding participation in distance education. In Brazil, distance education has been gaining a large share of enrollment, while in Chile its share of total enrollment remains very small. Colombia also has extensive participation of private institutions, which have recently assumed the majority of higher education enrollments in that country. By contrast, Argentina, among the four countries, has the lowest participation percentage of private institutions. Yet Brazil further distinguishes itself from these three countries: it still is the only one that permits for-profit institutions to function, and it is these institutions, especially large conglomerates, as publicly-traded companies with international investments, that offer the majority of opportunities for distance education in the country. With a significant reduction in public student financial aid, the massive spread of DE programs, with much lower tuition, has become an attractive option for a significant portion of Brazilian students, who must pay for their tuition while drawing low salaries. The absence of for-profit institutions in Argentina, Chile and Colombia can partially explain the vast difference between these countries and Brazil. Student mobilization in Colombia and Chile throughout the last decade also help to account for the absence of publicly-traded companies in the provision of higher education in these countries.

Another factor that should be considered has to do with the perception of the society and of the market in relation to distance programs. The attribution of a concept of poor quality to the distance programs can inhibit their growth in contexts in which the institution’s prestige and the education offered is greatly valued. There is evidence that this reasoning applies especially to Chile (Cortés, 2016). However, documentary research in government databases and periodicals that address higher education reveal that the issue of quality in distance education is almost unexplored. Only recently, a few countries started to provide enrollment data that distinguishes distance from face-to-face education. However, apart from Brazil, there is a lack of data on the quality of distance education. Paradoxically, Brazil, the country that offers the most data on this subject, revealing the lowest quality and highest dropout rate in distance courses, is the one in which distance education has grown the most. It is worth questioning whether the availability of statistical data on the quality of distance education is sufficient to shape public opinion on the topic, because if these data are not widely disseminated in the media, most people do not consider them when they decide between face-to-face and distance education.

Juxtaposing the precepts of the international entities such as the World Bank, OECD and UNESCO with the educational policies adopted in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Colombia, a major difference can be perceived between the manner in which Brazil has followed external recommendations in comparison to the other three. Even though the external factors are convergent or similar, the internal environment in each country influences the manner and pace at which this pressure solidifies in educational policies, as can be found in the distance education expansion trajectories of the four countries researched.

8. Final considerations

From the study conducted, it is obvious that the emergence of the DE modality and its evolution has been responsible for diverse changes in the higher education system and in the enrollment indices in this level of education in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Colombia. In this scenario, it is important to highlight that, overall, the countries in development have experienced external pressure exerted by international organizations such as the World Bank, OECD and UNESCO, with their recommendations of adopting distance education and privatizing higher education. However, the way these countries responded to these recommendations is not homogeneous. The most evident example of this diversity of reaction appears when Brazil is compared to the other countries investigated. While Brazil adopted the international recommendations, eliminating barriers to enter the educational market for corporate investment groups, including publicly-traded companies, other countries, like Chile and Colombia, experienced internal pressure that halted this tendency to privatize education.

Certainly the opening up of the market to for-profit businesses has facilitated Brazil’s unique explosion of distance education enrollment numbers. The companies form large conglomerates and are able to partner with various colleges, in search of reaching the largest number of students with the best market efficiency. As such, they have found in the DE model a guarantor of economic efficiency.

This investigation also identified a dearth of studies that deal with the comparison between the quality of face-to-face and distance higher education programs. In Brazil, where this evaluation has been taking place for several years, the evidence points to the inferior performance of DE courses. Consequently, it is suggested that the evaluation issue of distance higher education programs be tackled in future studies.

In conclusion, we believe that it is important to develop new studies, with the objective of learning how higher education is performing throughout Latin America, considering the conditions of access, permanence and evaluation, with an emphasis on distance education. It is necessary to comprehend the victories and progress made in this sphere on the continent, as well as to identify the main obstacles to be overcome in order for this modality to be able to reconcile quality and inclusion.