Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Portuguese Journal of Nephrology & Hypertension

versão impressa ISSN 0872-0169

Port J Nephrol Hypert vol.26 no.1 Lisboa jan. 2012

Primary glomerular diseases: variations in disease types seen in Africa and Europe

Ikechi Okpechi1, Maureen Duffield2, Charles Swanepoel1

1Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Department of Medicine

2Division of Pathology, Department of Clinical Laboratory Services Groote Schuur Hospital, University of Cape Town. Cape Town. South Africa.

ABSTRACT

Glomerular diseases account for a significant number of patients with chronic kidney disease worldwide. IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the predominant primary glomerular disease (PGD) seen across Europe, whereas in Africa, the prevalence of IgAN is not common. The most frequently described glomerular disease in Africa is mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (MCGN). The difference in the prevalence of PGDs seen in Africa and Europe may depend on several factors including genetic, socio-economic and demographic influences. Variations in exposure to infections (hygiene hypothesis) and patterns of Th1 and Th2 responses may also contribute significantly to observed differences.

Key-Words:Glomerulonephritis in Africa; Glomerulonephritis in Europe; Primary glomerulonephritis.

INTRODUCTION

Africa and Europe differ greatly when sociodemographic, economic and health care factors are considered. Approximately 70% of the least developed countries of the world are in Africa and to the WHO, health financing per capita total expenditure on health in 2009 for countries of Africa ranged from as low as US$3 in the Democratic Republic of Congo to US$612 in Botswana. In comparison, in Western Europe, average figures ranged well above US$25001.

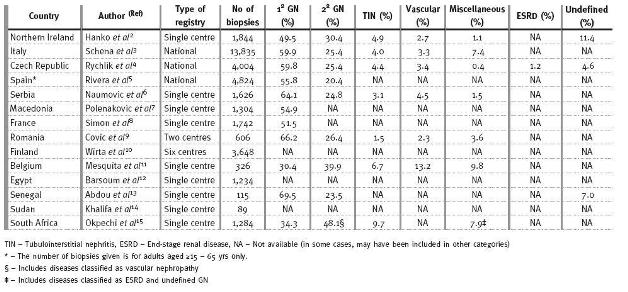

The pattern of kidney diseases is available for review in many parts of Europe with national or registries of kidney diseases (Table I)2-11. Such registries are nonexistent in Africa and data are often limited to case reports or single centre series. The major factor accounting for this situation is the lack of expertise to perform and interpret renal biopsies12-15.Categories of renal disease seen across Europe and Africa

The incidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) continues to rise worldwide because of the diabetic epidemic; however, glomerulonephritis (GN) has been shown to account for a significant proportion of patients with CKD and ESRD. The European Renal Association (ERA-EDTA) annual registry report of 2008 showed that GN accounted for 15% of all incident dialysis patients compared to 20% and 17% for diabetes and hypertension respectively16. Reports from different countries in Africa show that GN is presumed to be (most not biopsied) responsible for up to 52.1% of patients diagnosed with ESRD17-19. As Africa continues to battle the scourge of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the numerous renal diseases associated with it, patterns of primary glomerular diseases (PGD) seen in Africa may be changing. Worldwide, there is evidence for temporal variation in the frequency of primary glomerular diseases (PGD)2,9,10,20,21.

To our knowledge, there has never been a published report comparing the frequencies of PGD in Africa and Europe. The purpose of this review is to compare published results of the frequencies of PGD from renal biopsy registries across a selection of European countries with reports from countries in Africa. We will discuss observed similarities or differences in disease patterns between the two continents and what the implications of variations in frequency of PGD represents for burden of kidney disease in both continents. To do this, we searched PUBMED for publications reporting the results of analysis of either single centre, regional or national renal biopsy registries from countries of Europe and Africa alone. Since our purpose was not to perform a systematic analysis/review, we only included one publication per country. For countries with multiple publications on this subject, the publication with the largest number of subjects was used. Also, due to nonuniformity in presentation of results, only articles presenting data as percentage of total number of biopsies were included. We excluded case series, publications in uages other than English, paediatric renal registry reports and publications that did not include individual types of PGD in their analysis. Ten publications from Europe and four from Africa were thus selected for comparison.

TYPES OF RENAL DISEASE AND REGISTRY IN AFRICA AND EUROPE

Reports from Europe (except Belgium)11 and Africa (except South Africa)15 show that PGDs are the predominant form of renal disease seen on biopsy, usually accounting for more than half of all biopsies performed (Table I).

. In South Africa, we have shown that PGDs account for only 34.3% of renal diseases compared to 48.1% reported for all secondary glomerular diseases15. The major reason for this reversal was shown to be due to the number of renal biopsies performed in patients with HIV which had increased from 6.6% of biopsies performed in 2000 to 25.7% of biopsies performed in 200915. The prevalence of HIV infection in Europe is low and Ferreira et al.22in Portugal mention the greater predominance of the less virulent HIV-2 infection. In this study, HIV-2 did not directly cause renal disease. Consequently, HIVAN did not seem to contribute to the pattediseases reported in the European registries. The one exception is Belgium, where HIVAN accounted for 6.7% of all biopsies and 16.9% of secondary glomerular diseases11. Until we begin to see a significant reduction in the incidence and prevalence of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa, which has the highest burden of HIV in the world, secondary glomerular diseases due to HIV will continue to rise and will impact on the aetiology of CKD and ESRD in Africa. It will be interesting to see how HIV might dilute the biopsy prevalence of PGD reported in Europe over the next decade, given the high influx of African migrants into Europe.Only a few of the registries from Europe were from single centres; most were multicentre or national registry reports. Multicentre studies are often nearly impossible to perform in Africa where usually only a few centres have the capacity (manpower and infrastructure) to function effectively. There is therefore a need for the establishment of renal registries across several centres in Africa. This will only happen when comprehensive and integrated actions, led by governments, aided by the private sector, local NGOs and key players at all levels of the health system, begin to take place23.

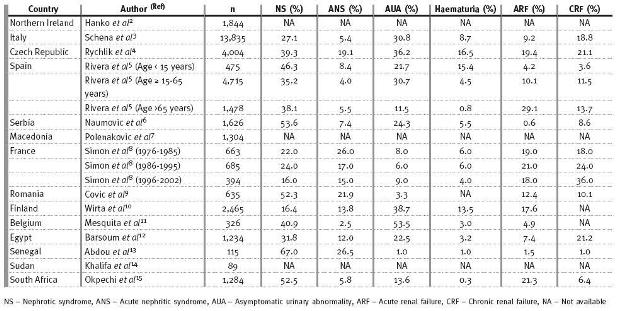

INDICATIONS FOR RENAL BIOPSIES: A REFLECTION OF WEALTH AND DISEASE?

As many PGD often present with the nephritic syndrome, it is not unexpected that this is the main indication for the performance of a renal biopsy in both continents (Table II). From European countries, only in Finland was renal biopsy for nephrotic syndrome much lower than that performed for asymptomatic urinary abnormalities 10. As AUA is often detected during medical examinations for other purposes and since the patients with AUA are often otherwise well, the percentage of renal biopsies performed for AUA may therefore hint at the level of healthcare in a country. Thus, several countries in Europe have a fairly high percentage of biopsies performed for patients with AUA compared to countries in Africa. In Senegal, only 1.0% of biopsies is performed for patients with AUA and may be a reflection of the amount of money available for healthcare1. In contrast to Senegal, Egypt and South Africa spend more on healthcare and therefore have a larger number of renal biopsies performed for patients with AUA; 22.5 and 13.6% of biopsies respectively (Table II).

Table II

Indications for renal biopsy: comparison between Europe and Africa

Also, biopsies performed for haematuria alone are seen to be much higher in Europe than in Africa. Biopsies performed for haematuria alone from studies in Europe is as high as 13.5 and 16.5%, respectively for Finland10 and the Czech Republic4. Only 0.3, 1.0 and 3.2% of biopsies are performed for patients presenting alone with haematuria in South Africa,15 Senegal12 and Egypt12 respectively. Although this might suggest differences in the clinical manifestations and types of glomerular diseases seen in both continents, it must also be said that local policies on performance of renal biopsy may contribute to these differences. The policy in Cape Town is that patients presenting with haematuria alone will have a urological examination. If no urological pathology is present and renal function is normal, follow-up will be arranged and the patient will not be biopsied. This may also explain the low frequency of IgA nephropathy (IgAN) reported in South Africa.

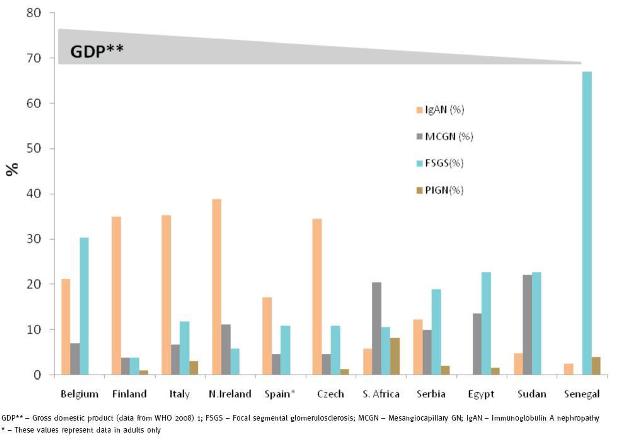

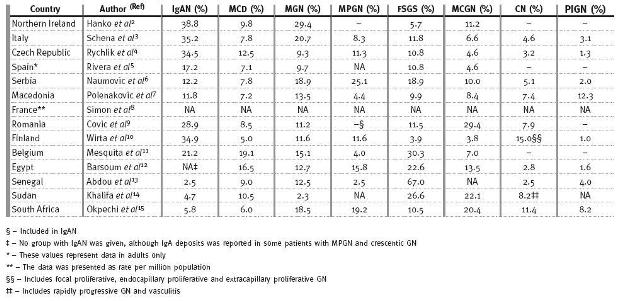

IGA NEPHROPATHY IS RARE IN BLACK AFRICANS: IS THIS A MYTH OR REALITY?

With a few exceptions, Fig. 1 and Table III clearly show that IgAN is the dominant form of PGD seen in Europe. IgAN accounted for 17.2, 34.5, 34.9, 35.2 and 38.8% of all PGDs reported from Spain, Czech Republic, Finland, Italy and Northern Ireland respectively2-5,10. However, IgAN is not commonly reported in Africans as it only accounted for 2.5 to 5.8% of PGDs for Senegal, Sudan and South Africa. A case report from Senegal and studies from South Africa have previously documented the rarity of IgAN in black Africans. Seedat et al.24 in an analysis of PGDs in 252 black South Africans found only 2 patients (0.8%) with IgAN. Also, Swanepoel et al.25 examined 872 biopsies done over a seven-year period and were only able to demonstrate a prevalence of 3.8% of IgAN and none of these patients were black. In 1999, Diouf et al.26 described for the first time a patient diagnosed with IgAN in Senegal. As fig. 1 illustrates, the frequency of IgAN appears to reflect a countrys GDP, as countries with the highest GDP had the highest frequencies of IgAN. The correlation between GDP and type of PGD has also been tested in South America where IgAN was found to occur at higher frequencies in countries like Uruguay and Argentina with high GDP compared to low GDP countries like Peru and Paraguay27. A reciprocal relationship between GDP and MCGN was observed in this hypothesis27.

Figure 1 IgA Nephropathy, FSGS and MCGN patterns in Europe and Africa based on country GDP.

Table III

Primary glomerular diseases: Europe and Africa

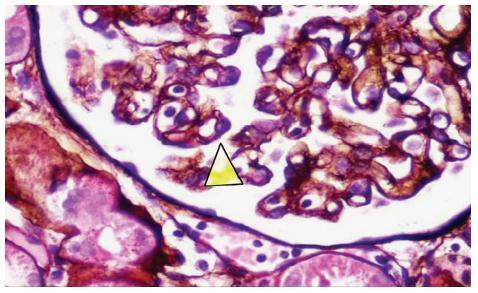

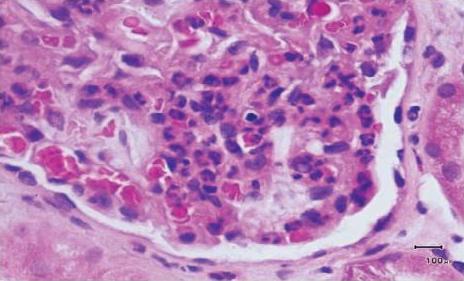

This may be explained by the hygiene hypothesis proposed by David Strachan in 1989 to explain the higher frequency of allergies seen in industrialised countries28. Early and frequent exposure to several infectious agents, common in developing nations, leads to a normal Th1 response. However, better public hygiene and less infections observed in industrialised nations is thought to result in persistence of the Th2 phenotype which thereby increases the risk for developing allergies. Most proliferative glomerulopathies for example, MCGN (fig. 2A), Mesangialproliferative GN (MPGN), and post-infectious GN (PIGN, fig. 2B) are largely driven by Th1 response and are often found to be quite common in developing countries29. This may explain the high prevalence of MCGN in South Africa, Senegal and Egypt. However, the frequencies we have shown for MPGN and PIGN do not seem to be any different between European and African countries (Table III). In Cape Town, we have anecdotally observed that a significant number of patients from prison, sent for investigation of renal disease, are often found to have MCGN. The causal relationship of MCGN with a prison environment, in our community, needs further investigation.

Figure 2A

Methenamine silver stain x400.Arrow sited along the peripheral basement membrane to show a double membrane and an interposed mesangial nucleus, diagnostic of mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis.

Figure 2B

H/E stain x400. Peripheral glomerular loop to show numerous neutrophils within the capillarity lumina and in the mesangium, typical of the early phase of acute post streptococcal glomerulonephritis.

Evidence for IgAN to be a Th2 dependent process comes from the report of several studies that have shown that in IgAN, Th2 dependent cytokines are mainly produced by the circulating T cells30. In murine models of IgAN, Th2 cytokines have also been shown to alter the glycosylation of IgA31. In a hypothesis-generating article, Johnson et al. have highlighted factors such as malnutrition, helminthic infections, psychological stress, depression and obesity that can modulate the balance between Th1 and Th2 responses and that can also explain key epidemiological differences seen across the world27. Beyond the mechanisms postulated in this hypothesis they added that differences in biopsy practice, as well as the environmental and genetic effects, may also play an important role leading to identification of IgAN in any population. Although IgAN may not be as common in black Africans as other PGDs, we certainly think that the very low rate of biopsies performed in many centres in Africa (in some cases no biopsies at all) and policies related to performance of biopsy in asymptomatic patients may account for this seemingly uncommon disease.

Although genetic factors are thought to contribute to IgAN, multiple genes with modest effect in combination with environmental factors are thought to play a role rather than single genetic defects. age of IgAN to chromosome 6q22-23 (IGAN1), chromosome 4q26-31 (IGAN2) and 17q12-22 (IGAN3) have been reported32,33. However, the study of Gharavi et al. showed that, only 60% of patients were ed to IgAN1, suggesting that other genes may be involved32. The exact role of genetic differences between Africans and Europeans, giving rise to the divergent frequencies of IgAN and MCGN is still to be determined.

OTHER PRIMARY GLOMERULAR DISEASES

Fig.1 also shows that focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) occurs at higher frequencies in Africans than in Europeans. FSGS is common in people of African descent and genetic studies have shown a strong association with some genes in African-Americans. The higher frequency of FSGS in Belgium compared to other European countries may be due to the large number of Africans represented in their registry (about 20-30% from 1994)11. The prevalence of primary FSGS has remained stable in Cape Town over the last decade; however, secondary FSGS due to HIV is seen frequently. The observed patterns of other PGDs such as MPGN, PIGN, Minimal Change Disease (MCD), Membranous Glomerulonephritis (MGN) and crescentic GN did not appear to differ much between reports from Europe and Africa.

CONCLUSION

Variations in the pattern of PGDs seen in Europe and Africa are more noticeably observed for IgAN, MCGN and FSGS. Although genetic factors could play a role, the influence of socio-economic and demographic factors may contribute substantially to the types of kidney diseases seen in both continents. In order to better understand the types and patterns of kidney diseases seen in Africa, the number and rate of renal biopsies will need to increase across centres in Africa. Due to emigration patterns from Africa, secondary glomerular diseases, mainly due to HIVAN may increase in Europe in the next decade.

References

1 World Health Organization. Health financing per capita total expenditure on health at average exchange rate (US$), 2009 (Available at: http://www.gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/health_financing/atlas.html?indicator=i3&date=2009(Accessed 21st December 2011) [ Links ]

2 Hanko JB, Mullan RN, ORourke DM, et al.The changing pattern of adult primary glomerular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:3050-3054 [ Links ]

3 Schena FP. Survey of the Italian Registry of Renal Biopsies.Frequency of the renal diseases for 7 consecutive years. The Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1997;12:418-426 [ Links ]

4 Rychl´ık I, Jancov´a E, Tesar V, et al. The Czech registry of renal biopsies. Occurrence of renal diseases in the years 1994-2000. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004 ;19:3040-3049 [ Links ]

5 Rivera F, López-Gómez JM, Pérez-García R, et al.Frequency of renal pathology in Spain 1994–1999. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002 ;17:1594-1602 [ Links ]

6 Naumovic R, Pavlovic S, Stojkovic D, et al. Renal biopsy registry from a single centre in Serbia: 20 years of experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:877-885 [ Links ]

7 Polenakovic MH, Grcevska L, Dzikova S. The incidence of biopsy proven primary glomerulonephritis in the Republic of Macedonia long-term follow-up. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003;18:S26-S27 [ Links ]

8 Simon P, Ramee MP, Boulahrouz R, et al. Epidemiologic data of primary glomerular diseases in western France. Kidney Int 2004;66:905-908 [ Links ]

9 Covic A, Schiller A, Volovat C, et al. Epidemiology of renal disease in Romania: a 10 year review of two regional renal biopsy databases. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006;21:419-424 [ Links ]

10 Wirta O, Mustonen J, Helin H, Pasternack A. Incidence of biopsy-proven glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:193-200 [ Links ]

11 Mesquita M, Fosso C, Bakoto Sol E, et al. Renal biopsy findings in Belgium: a retrospective single center analysis. Acta Clin Belg 2011;66:104-109 [ Links ]

12 Barsoum RS, Francis MR. Spectrum of glomerulonephritis in Egypt. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2000;11:421-429 [ Links ]

13 Abdou N, Boucar D, El Hadj, et al. Histopathological profiles of nephropathies in senegal. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2003;14:212-214 [ Links ]

14 Khalifa EH, Kaballo BG, Suleiman SM, et al. Pattern of glomerulonephritis in Sudan: histopathological and immunofluorescence study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2004;15:176-179 [ Links ]

15 Okpechi I, Swanepoel C, Duffield M, et al. Patterns of renal disease in Cape Town South Africa: a 10-year review of a single-centre renal biopsy database. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:1853-1861 [ Links ]

16 Stel VS, van de Luijtgaarden MW, Wanner C, Jager KJ; on behalf of the European Renal Registry Investigators. The 2008 ERA-EDTA Registry Annual Report-a précis. NDT Plus 2011;4:1-13 [ Links ]

17 Arogundade FA, Sanusi AA, Akinsola A. Epidemiology of chronic renal failure in Nigeria: Is there a change in trend. Nephrology 10:(WCN 2005 Abstracts) 2005,56 (abstr;suppl 1) [ Links ]

18 Matekole M, Affram K, Lee SJ, et al. Hypertension and end-stage renal failure in tropical Africa. J Hum Hypertens 1993;7:443-446 [ Links ]

19 Diouf B, Ka EF, Niang A, et al. Etiologies of chronic renal insufficiency in a adult internal medicine service in Dakar. Dakar Med 2000;45:62-65 [ Links ]

20 Swaminathan S, Leung N, Lager DJ,et al. Changing incidence of glomerular disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota: a 30-year renal biopsy study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;1:483-487 [ Links ]

21 Zhou F, Zhao M, Zou W, et al. The changing spectrum of primary glomerular diseases within 15 years: a survey of 3331 patients in a single Chinese centre. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:870-876 [ Links ]

22 Ferreira AC, Carvalho D, Carvalho F, et al. Renal pathology in Portuguese HIV-infected patients. Port J Nephrol Hypert 2011 ;25:275-283 [ Links ]

23 Katz IJ, Gerntholtz T, Naicker S. Africa and nephrology: the forgotten continent. Nephron Clin Pract 2011;117:c320-7 [ Links ]

24 Seedat YK, Nathoo BC, Parag KB, et al. IgA nephropathy in blacks and Indians of Natal. Nephron 1988;50:137-141 [ Links ]

25 Swanepoel CR, Madaus S, Cassidy MJ, et al. IgA nephropathy-Groote Schuur Hospital experience. Nephron 1989;53:61-4 [ Links ]

26 Diouf B, Diao M, Niang A, et al. First case of primary IgA glomerulonephritis (Bergers disease) in Senegal. Dakar Med 1999;44:140-142 [ Links ]

27 Johnson RJ, Hurtado A, Merszei J, Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Feng L. Hypothesis: dysregulation of immunologic balance resulting from hygiene and socioeconomic factors may influence the epidemiology and cause of glomerulonephritis worldwide. Am J Kidney Dis 2003 ;42:575-581. [ Links ]

28 Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ 1989;299:1259-1260 [ Links ]

29 Holdsworth SR, Kitching AR, Tipping PG. Th1 and Th2 T helper subsets affect patterns of injury and outcomes in glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 1999;55:1198-1216 [ Links ]

30 Lim CS, Zheng SM, Kim YS, et al. Th1/Th2 predominance and proinflammatory cytokines determine the clinicopathological severity of IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001;16:269-275 [ Links ]

31 Chinatalacharuvu SR, Emancipator SN. The glycosylation of IgA produced by murine B cells is altered by Th2 cytokines.J Immunol 1997;159:2327-2333 [ Links ]

32 Gharavi AG, Yan Y, Scolari F, et al. IgA nephropathy, the most common cause of glomerulonephritis, is ed to 6q22-23. Nat Genet 2000;26:354-357 [ Links ]

33 Bisceglia L, Cerullo G, Forabosco P, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in Italian families with IgA nephropathy: suggestive age for two novel IgA nephropathy loci. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:1130-1134 [ Links ]

Prof. Charles Swanepoel

Division of Nephrology and Hypertension

Department of Medicine Groote Schuur Hospital, University of Cape Town. Cape Town, South Africa

E-mail: Charles.Swanepoel@uct.ac.za

Conflict ofinterest statement. None declared.

Received for publication: 05/01/2012

Accepted: 20/01/2012