Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Portuguese Journal of Nephrology & Hypertension

versão impressa ISSN 0872-0169

Port J Nephrol Hypert vol.26 no.1 Lisboa jan. 2012

Clinical and pathological findings in women withFabry disease

Ana Natário1,2, Helena Viana2, Maria João Galvão2, Fernanda Carvalho2

1 Nephrology Department, Centro Hospitalar de Setúbal. Setúbal Portugal.

2 Renal Pathology Laboratory, Nephrology Department, Hospital Curry Cabral. Lisbon, Portugal.

ABSTRACT

Introduction.Fabry disease is a rare metabolic disorder caused by the genetic deficiency of the lysosomalhydrolase alpha-galactosidase A, located on chromosome X. Females with the defective gene are more than carriers and can develop a wide range of symptoms. Nevertheless, disease symptoms generally occur later and are less severe in women than in men. The enzyme deficiency manifests as aglycosphingolipidosis with progressive accumulation ofglycosphingolipids and deposit of inclusion bodies inlysosomes giving a myelinlike appearance.

Patients and Methods.Records of renal biopsies performed on adults from 1st January 2008 to 31st August 2011, were retrospectively examined at the Renal Pathology Laboratory. We retrieved biopsies diagnosed withFabry disease and reviewed clinical and laboratory data and pathology findings.

Results.Four female patients with a mean age of 49.3 ±4.5 (44-55) years were identified. The mean proteinuria was 0.75± 0.3 g/24h (0.4-1.2) and estimatedglomerular filtration rate (CKD EPI equation) was 71 ±15.7 ml/min/1.73m 2 (48-83). Three patients experienced extra-renal organ involvement (cerebrovascular, cardiac, dermatologic, ophthalmologic and thyroid) with distinct severity degrees. Leukocyte α-GAL A activity was below normal range in the four cases but plasma and urinary enzymatic activity was normal.

Light microscopy showed predominant vacuolization of thepodocyte cytoplasm and darkly staining granular inclusions on paraffin and plastic-embedded semi-thin sections. Electron microscopy showed in three patients the characteristic myelin-like inclusions in thepodocyte cytoplasm and also focal podocyte foot process effacement. In one case the inclusions were also present in parietalglomerular cells, endothelial cells ofperitubular capillary and arterioles.

Conclusion. Clinical signs and symptoms are varied and can be severe among heterozygous females with Fabry disease. Intracellular accumulation of glycosphingolipids is a characteristichistologic finding of Fabry nephropathy. Since this disease is a potentially treatable condition, its early identification is imperative. We should consider it in the differential diagnosis of any patient presenting with proteinuria and/or chronic kidney disease, especially if there is a family history of kidney disease.

Key-Words:Fabry disease;glomerulopathy; renal biopsy.

INTRODUCTION

Fabry disease (FD) is a progressive, X-linked inherited disorder of glycosphingolipid metabolism due to deficient or absent lysosomal α-galactosidase A (α-GAL A) activity. This results in progressive accumulation ofglobotriaosylceramide (Gb3 or GL-3) and relatedglycosphingolipids withinlysosomes in a variety of cell types, including capillary endothelial cells, renal, cardiac and nerve cells1.

The incidence off Fabry disease has been estimated to be 1:117,000 overall births2. The age of symptom onset and the age of diagnosis tend to be approximately 10 years later in females than males3. There is often significant delay in the diagnosis4.

Phenotype differences are due in part to random X-chromosome inactivation, resulting in considerable variability in α-GAL A activity among carriers and within one carrier individual among various tissues or regions of a single tissue4.

The classical phenotype presents with early dermatologic, ophthalmologic, and peripheral nervous system involvement. Renal, cardiac andcerebrovascular complications are major causes of morbidity and mortality in adults1.

Renal impairment often begins with microalbuminuria andproteinuria in the second to third decade of life.Isosthenuria accompanied by alterations in tubularreabsorption, secretion and excretion also develops1. By adulthood, renal failure frequently becomes a major complication of Fabry disease, with more than half of males eventually developing advanced renal failure or end-stage renal disease (ESRD)5.

Heterozygous female individuals can develop a wide range of symptoms, ranging from asymptomatic to overt disease6. The majority of females have slowly progressive kidney disease, but a smaller subset seem to be more seriously affected with progression to ESRD at the same median age as men7.

Classically, renal lesions result from Gb3 deposition in thelysosomes ofpodocytes, glomerular endothelial, parietal epithelial, mesangial and interstitial cells that may lead to progressivemicrovascular dysfunction, occlusion and ischaemia, with subsequent development of segmental and globalglomerular sclerosis, tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis8-10.Podocyte injury might correlate directly withproteinuria and play a pivotal role in the development and progression off Fabry nephropathy11.

Glycosphingolipid storage also occurs in the epithelium of the loop ofHenle and the distal tubules, and in the endothelial and smooth muscle cells of the renal arterioles1.

Kidney biopsy may be useful as a baseline assessment and in patients with atypical presentations, including a repeat kidney biopsy when the disease is progressing despite therapy1. In some cases, females can develop the same kidney histopathology as males8,12,13.

The aim of this study is to review the clinicopathological findings of females with Fabry disease, whose renal biopsies were analysed in a singlenephropathology laboratory.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Four renal biopsies performed on four adult females andanalysed at our institution from 1st January 2008 to 31st August 2011 were retrospectively examined.

We recorded the following data from each patient: age, gender, race, indication for renal biopsy (clinical syndrome), clinical manifestations in other organs, GLA gene mutation, plasma and leukocyte α-GAL A levels and urinary activity measurements.

Renal biopsy specimens were stained and analysed by light microscopy (LM),immunofluorescence (IMF) and electron microscopy (EM). Routine LM examination was performed on haematoxylin and eosin (HE), periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), Jones methenamine silver (SM), andtrichrome stains (TR). Histological findings were scored by LM, with respect to glomerular and interstitial changes as 0, none; 1, mild (<25%); 2, moderate (25-50%); and 3, severe change (>50%)8. Vascular changes wereanalysed forintimal thickening andhyalinosis using the same scoring system.

We reviewed the semi-thintoluidine blue-stain sections that were prepared as survey sections for electron microscopy.

All specimens were studied by IMF using antiimmunoglobulin (A, G and M), anti-C3, C4, C1q of complement and anti-albumin antibodies.

Electron microscopy images were reviewed in all cases.

RESULTS

Clinical findings

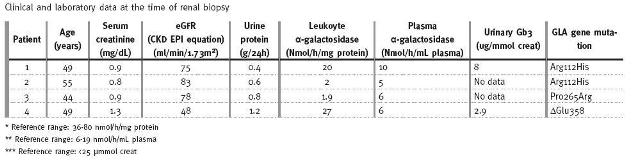

We retrospectively identified four female patients withFabry disease in our renal biopsy files, and their clinical and laboratory data are summarised in Table I.

Table I

Clinical and laboratory data at the time of renal biopsy

All patients were Caucasian, ranging in age from 44 to 55 years (mean 49.3±4.5). Estimatedglomerular filtration rate (CKD EPI equation) was 71±15.7 ml/min/1.73m2(48-83). Three patients with a mean age of 39.3±6.0 (33-45) years were diagnosed with hypertension and, in these cases, 24-hour urine total protein (mean 0.75±0.34 g/24h) was measured while on treatment withangiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and/orangiotensin receptor blockers.

Two patients were sisters (patients 1 and 2) and all had at least one case of first-degree family history of renal disease.

The indications for renal biopsy werenonnephrotic proteinuria in three patients and chronic renal failure withproteinuria in the other.

In three cases the diagnosis was established by biochemical and genetic studies prior to renal biopsy. Skin biopsy ofangiokeratomas performed in our nephropathology centre (Fig. 1) allowed the diagnosis in one case (patient 3).

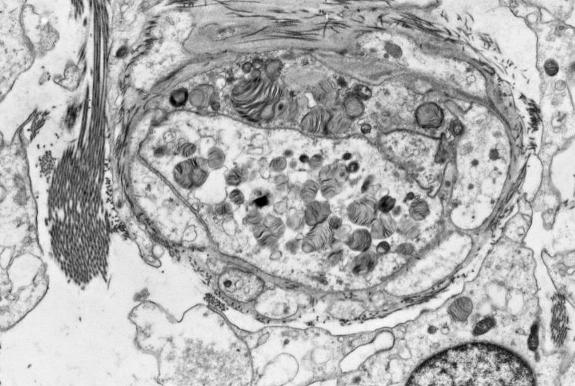

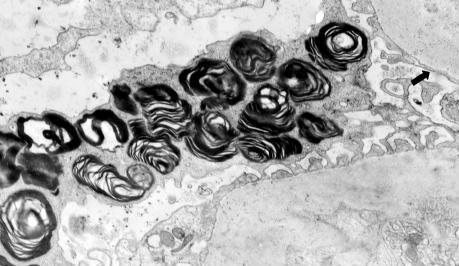

Figure 1

Electron microscopy of skin biopsy (patient 3) of a small superficial angioma showinglysosomal inclusion with myelin-like figures within endothelial cells and capillary lumen).

All the females had leukocyte α-GAL A activity below normal range but plasma and urinary enzymatic activity was normal.

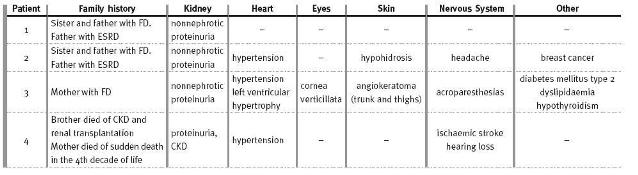

Clinical manifestations were provided by the patients' physicians and are shown in Table II. Cardiovascular involvement was exhibited as hypertension in three patients and also left ventricular hypertrophy in other case. Cryptogenic ischaemic stroke occurred in one patient at the age of 38 years.

Table II

Clinical manifestations in femaleFabry disease patients

Ophthalmologic, cutaneous lesions, thyroid dysfunction and peripheral neuropathic pain were present in one patient. Finally, in one case the only manifestation was non-nephroticproteinuria.

Light microscopy

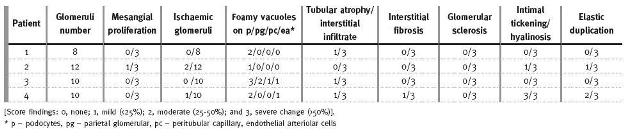

On average, 10±1.6 (range 8-12)glomeruli were present for light microscopic assessment, and 2.8±1.3(range 1-4)glomeruli were examined ontoluidine blue-stained semi-thin sections. Renal pathology from light microscopy is described in Table III.

Table III

Light microscopy findings in renal biopsies

LM showed in all patients varying degrees of hypertrophic glomerular visceral epithelial cells distended with foamy appearing vacuoles (Fig. 2A), corresponding to extracted Gb3 deposits. There were also vacuoles in parietalglomerular, endothelial cells ofperitubular capillary and arterioles in patient 3.

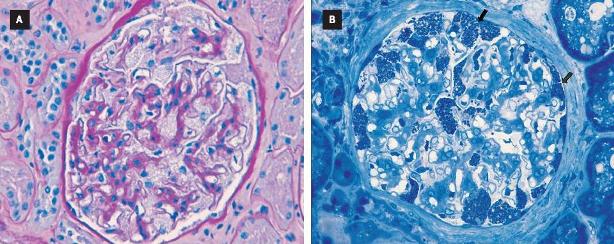

Figure 2

Light microscopy in Fabry disease

(A) Renal biopsy of patient 4 with a glomerulus showing hypertrophic glomerular podocytes distended with foamy appearing vacuoles (PAS stain; magnification, x400)

(B) Renal biopsy of patient 3 with a glomerulus showing extensive inclusion bodies of glycolipid in podocytes and parietal cells (arrows; toluidine blue stain; magnification, x 400)

In one biopsy there was mildmesangial widening. In thetubulo-interstitial compartment, two patients had mild interstitial fibrosis, a chronic inflammatory infiltrate and tubular atrophy (less than 5%).Glomerular sclerosis (segmental or global) was not observed.

Vascular involvement was observed in two patients: arteriolar thickening,hyalinosis and elastic duplication, which led to the initial histological diagnosis ofnephroangiosclerosis in one of the cases. The female patient with diabetes mellitus type 2 showed no lesions of diabetic nephropathy.

Semi-thin sections withtoluidine blue showed fine but darkly staining granular inclusions (Fig. 2B) in varying degrees in the cytoplasm ofpodocytes in all patients. The most prominent location of the inclusions was inpodocytes but in two cases (patients 3 and 4) it was present inperitubular capillary,glomerular endothelial and vascular intimal cells.

On frozen sections underpolarised light, theglycosphingolipids showed birefringence andautofluorescence (Fig. 3).

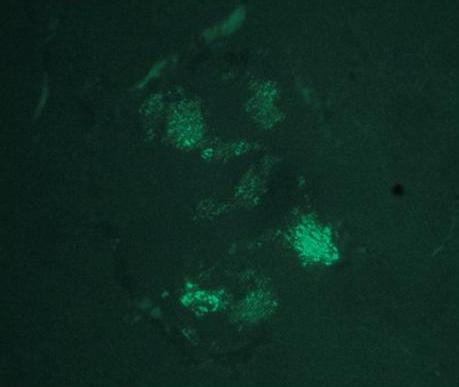

Figure 3

Light microscopy with polarised light (patient 3) showingglycosphingolipids within aglomeruli that are birefrigent and exhibitautofluorescence (magnification, x 400)

Immunofluorescence was negative in all cases (including albumin and Ig G in the diabetic female).

Electron microscopy

All the biopsies wereanalysed by electron microscopy. In three specimens,podocyte inclusions that varied from granular to concentriclamellated were demonstrated (Fig. 4) and in one biopsy it was also found on peritubular capillaries, parietalglomerular cells and arterial endothelial cells. Inclusions were surrounded by a single unit membrane, indicating their location inlysosomes. Areas of focal fusion ofpodocyte foot processes were present in three biopsies. No lesions were found in dense membrane of the glomeruli.

Figure 4

Electron microscopy in renal biopsy of patient 1. Accumulation of storage material, with the appearance of lamellated membrane structures is demonstrated in the secondarylysosomes ofpodocytes. There is focal foot process effacement (arrow).

Unfortunately in one patient there was no sample for electron microscopy. The diagnosis of Fabry disease was made afterwards with identification of GLA mutation.

DISCUSSION

In this case series of heterozygous females, clinical signs and symptoms varied widely. This phenotypic heterogeneity is thought to be partly due tolyonisation, a process whereby one copy of the X-chromosome is randomly inactivated in all cells of the female embryo1. Therefore, heterozygous females are essentially a mosaic of normal and mutant cells in varying proportions21.

The degree of symptoms depends on the residual enzymatic activity of α-GAL A: females can have anywhere from near-normal levels to no active enzyme1. Of the 1077 females enrolled in theFabry Registry, 69.4% had symptoms and signs of FD and twenty percent experienced majorcerebrovascular, cardiac, or renal events at a median age of 46 years5.

One female of our case series suffered an ischaemic stroke at the age of 38 years and on light microscopy, vascular abnormalities of severe hypertension superimposed on the changes of FD were observed. There is a high prevalence of hypertension, cardiac disease and renal disease in patients who have had a stroke in the context of FD22. Data from theFabry Registry22 and theFabry Outcome Survey23 have shown that the majority of strokes in FD are due to small vessel events. In a large cohort of young Portuguese patients the prevalence of GLA missense mutations was 3.8% in patients with cryptogenic stroke, and these mutations were associated with residual α-galactosidase activity levels much higher than those observed in classically affectedFabry patients14.

Incidental findings of corneal opacity by ophthalmologists can be another sign of FD. Corneal changes (corneaverticillata), rarely disturbing visual acuity, are frequently encountered in case series1 and was detected in one of our patients. Hearing loss has also been reported1,15.

In a small study, subclinical hypothyroidism was found in 36.4% of the patients16. Hypothyroidism was detected in one of our four cases.Faggiano et al. consider that endocrine work-up should be recommended in all patients suffering from FD17.

Proteinuria and CKD are important manifestations of Fabry disease7. All the female patients had proteinuria and only one had moderate renal function impairment.

According to some authors,proteinuria and/or a reducedglomerular filtration rate may be found in 40% of adult females7,18.Proteinuria was recently shown to be an important risk factor for progression of kidney dysfunction in Fabry disease19,20 with a much greater predictive value for men than women20.

Deegan et al. found that proteinuria was not associated with a more rapid decline in GFR in females18.

An international effort has been mounted to create a standardised scoring system of the extent and severity of renal involvement, supporting the role of kidney biopsy in the baseline evaluation off Fabry nephropathy. This International Study Group considered that optimal slides for scoring should ideally include >10glomeruli for light microscopic assessment, and at least 3glomeruli for semi-thin section scoring8. Renal specimens of our study contained a mean glomeruli number of 10±1.6 (range 8-12) present for light microscopy and 2.8±1.3 (range 1-4) ontoluidine blue-stained semi-thin sections.

Vacuolisation ofpodocytes and epithelial cells is a characteristic histological finding 8.Glomerular parietal epithelial cells are particularly involved in females with severe GLA gene mutations13 and this was found in patient 3 that had serious extra-renal manifestations of FD.

Fogo et al. found that arteriolar hyalinosis was similar in both genders, but females had significantly more arterialhyalinosis which was probably related to their significantly higher age8. We detected mild and severe arteriolar hyalinosis, respectively, in two biopsies.

Although mild interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy was found in only half of our patients, it should be emphasised that chronicglomerular and interstitial damage develops early in the course off Fabry disease, and the absence of typical clinical signs of CKD does not rule out Fabry nephropathy8. Our results are in agreement with previous series off Fabry patients, showing histological changes before renal function is decreased. Renal biopsy in female patients with FD may therefore be important for establishing the diagnosis and characterisation of renal lesions.

During the study, it became clear to us that histological findings suggestive off Fabry nephropathy (e.g.vacuolisation) may be missed on routine histological sections unless there is a strong clinical suspicion. However, semi-thin sections are best forcharacterising podocyte Gb3 inclusions8.

Cellular inclusions of Gb3 within lysosomes have been described by various names, including zebra bodies and myelin figures, according to different morphologies of their pattern oflamellation.Podocytes and distal tubular epithelial cells have been described as containing the highest concentrations of Gb324. In some cell types, inclusions appear as small, dark, dense-beaded granules; in others, they appear as larger complex laminated bodies24, as seen in this case series.

Noteworthy is that none of our patients had an history of taking medications known to causeFabrylike morphologic changes, such aschloroquine,amiodarone, or aminoglycosides25-27.

Immunofluorescence was negative in all cases. According to literature, routineimmunofluorescence microscopy is usually negative but inglomeruli with advanced lesions, immunoglobulin M, A, and complement components (C3 and C1q) may be detectable in capillary walls andmesangial regions showing a segmental distribution and granular pattern24. In symptomatic individuals, the diagnosis of FD can be established on the basis of low activity of α-GAL A in plasma, leukocytes or cultured skin fibroblasts28.

There is significant overlap in the α-GAL A activity levels of carrier females and the general population; thus, α-GAL A activity may not reliably distinguish the affected (carrier) from unaffected (noncarrier) women. As shown in this series, females had a normal amount of plasma α-GAL A enzyme activity and still carried the defective gene.

For females with normal to low-normal α-GAL A, a genetic test is needed for accurate diagnosis15.

Mutation subtypes of FD may have impact on disease progression9. The mutation Arg112His demonstrated in patients 1 and 2 is predominantly associated with residual enzyme activity and a mild variant phenotype of FD29 which is consistent with our clinical and histological findings. There are several limitations whenanalysing our data, especially in rare diseases where the limited number of cases may not be representative of theFabry female population. The prevalence of CKD and ESRD in the general population is much higher than in Fabry disease and, particularly in patients carrying GLA mutations associated with significant residual enzyme activity, it should be noted that the cause of CKD may not always be a consequence off Fabry disease.

The diagnosis off Fabry disease among patients without a positive family history has been a challenge to nephrologists and sinceFabry disease is a potentially treatable condition it is imperative to consider it in the differential diagnosis of any patient presenting withproteinuria and/or chronic kidney disease, especially if there is a family history of kidney disease30.

CONCLUSION

Clinical signs and symptoms are varied and can be severe among heterozygous females withFabry disease. Histological renal findings are notorious even in women with little clinical involvement – myelin-like structures were found withinlysosomes in many renal cells.Glomerular sclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis are minimal in females with no clinical expression of renal disease.

Fabry disease nephropathy should be considered for diagnosis of any patient presenting with CKD, especially in those with proteinuria and family history of renal disease.

This study should raise the awareness of this rare disease among nephrologists and other specialists that are likely to encounter unrecognisedFabry female patients to improve early diagnosis.

References

1 Germain DP.Fabry disease. Orphanet J RareDis 2010;5:30 [ Links ]

2 Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ, Clague AE, Carey WF. Prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders. JAMA 1999;281:249-254 [ Links ]

3 MacDermot KD, Holmes A, Miners AH. Anderson-Fabry disease: Clinical manifestations and impact of disease in a cohort of 60 obligate carrier females. J Med Genet 2001;38:769-775 [ Links ]

4 Anderson-Fabry disease: a nephrology perspective. J Am SocNephrol 2002;(Ssuppl 2);13:S125-S153 [ Links ]

5 Wilcox WR, Oliveira JP, Hopkin RJ, et al. Females withFabry disease frequently have major organ involvement: lessons from the Fabry Registry. Mol GenetMetab 2008;93:112-128 [ Links ]

6 Warnock DG, Daina E,Remuzzi G, West M. Enzyme replacement therapy andFabry nephropathy. Clin J Am SocNephrol 2010;5:371-378 [ Links ]

7 Ortiz A, Oliveira JP, Waldek S, Warnock DG,Cianciaruso B,Wanner C. Nephropathy in males and females with Fabry disease: cross-sectional description of patients before treatment with enzyme replacement therapy.Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:1600-1607 [ Links ]

8 Fogo AB,Bostad L,Svarstad E, et al. Scoring system for renal pathology inFabry disease: report of the International Study Group off Fabry Nephropathy (ISGFN).Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25:2168-2177 [ Links ]

9 Branton MH,Schiffmann R,Sabnis SG, et al. Natural history of Fabry renal disease: Influence of alpha-galactosidase A activity and genetic mutations on clinical course. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002; 81:122-138 [ Links ]

10 Alroy J,Sabnis S, Kopp JB. Renal pathology inFabry disease. J Am SocNephrol 2002;13:S134-S138 [ Links ]

11 Najafian B,Svarstad E, Bostad L, et al. Progressivepodocyte injury and globotriaosylceramide (GL-3) accumulation in young patients withFabry disease. KidneyInt 2011;79: 663-670 [ Links ]

12 Gubler MC, Lenoir G, Grunfeld JP,Ulmann A, Droz D,Habib R. Early changes inhemizygous and heterozygous patients withFabrys disease. KidneyInt 1978;13:223-235 [ Links ]

13 Valbuena C,Carvalho E,Burstorff M, et al. Kidney biopsy findings in heterozygousFabry disease females with early nephropathy. VirchowArch 2008;453:329-338 [ Links ]

14 Baptista MV, Ferreira S, Pinho-e-Melo T, et al. Mutations of the GLA gene in young patients with stroke: the POTYSTROKE Study. Stroke 2010; 41:431-436 [ Links ]

15 Keilmann A,Hajioff D,Ramaswami U. Ear symptoms in children with Fabry disease: data from theFabry Outcome Survey. J InheritMetabDis 2009;32:739-744 [ Links ]

16 Hauser AC,Gessl A, Lorenz M,Voigtlander T,Fodinger M, Sunder-Plassmann G. High prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism in patients with Anderson-Fabry disease. J InheritMetabDis 2005;28:715-722 [ Links ]

17 Faggiano A,Pisani A,Milone F, et al. Endocrine dysfunction in patients withFabrydisease. JClinEndocrinol Metab 2006; 91:4319-4325. [ Links ]

18 Deegan PB,Baehner AF,Barba Romero MA, et al. Natural history off Fabry disease in females in theFabry Outcome Survey. J Med Genet 2006;43:347-352 [ Links ]

19 Banikazemi M,Bultas J,Waldek S, et al.Agalsidase-beta therapy for advanced Fabry disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:77-86 [ Links ]

20 Wanner C, Oliveira JP, Ortiz A, et al. Prognostic indicators of renal disease progression in adults withFabry disease: natural history data from theFabry Registry.Clin J Am SocNephrol 2010;5:2220-2228 [ Links ]

21 Germain DP. Genetics of Fabry disease: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Presse Med 2007;36:S14-S19 [ Links ]

22 Sims K,Politei J,Banikazemi M, Lee P. Stroke inFabry disease frequently occurs before diagnosis and in the absence of other clinical events: natural history data from theFabry Registry. Stroke 2009;40:788-794 [ Links ]

23 Fellgiebel A, Muller MJ, Ginsberg L. CNS manifestations off Fabrys disease. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:791-795 [ Links ]

24 Mehta A, Beck M, Sunder-Plassmann G.Fabry disease: perspectives from 5 years of FOS. OxfordPharmaGenesis 2006;Chapter 21. [ Links ]

25 Albay D, Adler SG, Philipose J,Calesdbetta CC, Romansky SG, Cohen AH.Chloroquineindeuced lipidosis mimickingFabry disease. ModPathol 2005;18:733-738 [ Links ]

26 Liu FLW, Cohen RD, Downar E, et al.Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity: functional andultrastructural evaluation. Thorax 1986;41:100-105 [ Links ]

27 Coulon G, Saint-Hillier Y, Carbillet JP et al. Urinary myelin bodies and thenephrotoxicity ofaminoglycosides.Nephrologie 1984;5:107-114. [ Links ]

28 Chamoles NA, Blanco M, Gaggioli D.Fabry disease: enzymatic diagnosis in dried blood spots on filter paper.Clin ChimActa 2001;308:195-196 [ Links ]

29 Eng CM,Niehaus DJ, Enriquez AL,Burgert TS,Ludman MD,Desnick RJ.Fabry disease: twenty-three mutations including sense and antisense CpG alterations and identification of adeletional hot-spot in the alpha-galactosidase A gene. Hum Mol Genet 1994;3:1795-1799 [ Links ]

30 Fervenza FC,Torra R, Warnock DG. Safety and efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy in the nephropathy off Fabry disease. Biologics 2008;2:823-843 [ Links ]

Dr Ana Natário

Departmentof Nephrology, Centro Hospitalar Setúbal

Rua Camilo Castelo Branco

2910-446 Setúbal, Portugal

e-mail: ananatario@hotmail.com

Conflict of interest statement.None declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the physicians off Fabry disease patients: Dr CarlosBarreto (Setúbal), Dr JesusGarrido and Dr JoanaVidinha (Viseu), Dr IsabelPataca (Lisboa) for their contribution to clinical data collection.

Received for publication: 29/12/2011

Accepted in revised form: 16/02/2012