CLINICAL VIGNETTE

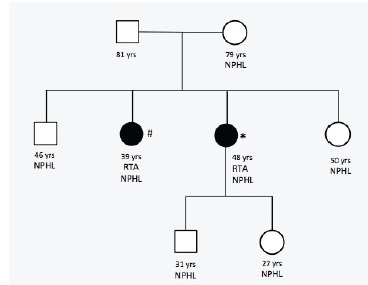

We present the case of a 48-year-old female patient with a history of calcium and phosphate oxalate urolithiasis and recurrent urinary tract infections who underwent multiple urology surgeries over a 20-year period due to obstructive calculi. Bilateral medullary nephrocalcinosis was documented by renal ultrasound in 2004. Family history of recurrent renal calculi was also reported among her mother and siblings (Figure 1).

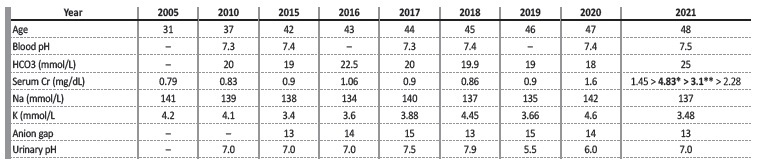

Our patient was first observed in the nephology outpatient clinic in 2010 after the investigation of her recurrent lithiasis led to the diagnosis of incomplete renal tubular acidosis (RTA). At this time, laboratory blood exams showed normal renal function (serum Cr 0.83mg/dL). Arterial blood gas test revealed normal pH and low bicarbonate level of 20 mmol/L. Urinalysis showed pH that never dropped below 7.0. Urinary 24h calcium and oxalate excretion was found to be normal. She began treatment with urinary alkalinizers at the age of 35. Compliance to treatment was limited due to intolerance and she was lost to nephrology follow-up in 2014. She developed progressive deterioration of renal function and in 2020 her serum creatinine (sCr) was 1.6mg/dL (Table I). In April 2021 she was admitted to the hospital due to obstructive pyelonephritis with multiple kidney abscesses. Her renal function worsened further with this episode, and she had a sCr of 3.0mg/dL on discharge. She returned nephrology in a stage of advanced chronic kidney disease. In the meantime, as part of the diagnostic work-up of one of her sister’s recurrent bouts of lithiasis, genetic testing revealed heterozygosity for a pathological genetic variant of the SCL4A1 gene (c.1838C>T p. ser613Phe). We performed sequencing of SCL4A1 gene in our patient and this showed the same pathogenic variant in heterozygosity.

WHAT TYPE OF TUBULAR DISORDER IS PRESENT? WHAT GAVE IT AWAY?

The patient’s laboratory analysis demonstrated normal anion gap metabolic acidosis in the absence of systemic acidemia (Table I). The inability to acidify urine occurs in type 1 distal RTA. This may occur either due to impairment in hydrogen ion secretion (secretor defect), or due to abnormally permeable distal tubule leading to a backleak of secreted hydrogen ions in the distal tubule (gradient defect).1 As a result, titratable acid and urinary ammonia excretion are minimized, which leads to systemic acidosis and persistently high urine pH (>5.5).

In patients with minimal disturbances in blood pH and plasma HCO3−, as is the case of our patient, incomplete RTA is most likely and urinary acidification tests could help diagnosis. Traditionally, such tests involved either oral NH4Cl administration to induce metabolic acidosis, followed by serial measurement of urine pH, or, alternatively, the simultaneous administration of furosemide and mineralocorticoid fludrocortisone to increase distal Na+ delivery, stimulate distal H+ secretion with subsequent measurement of drop in urine pH below 5.5.1,2 In current clinical practice such provocative tests are rarely performed.

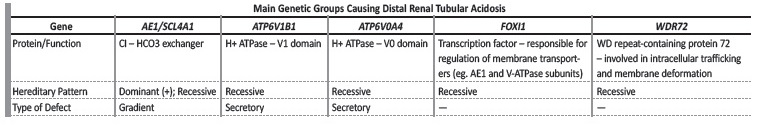

Distal RTA may be primary (either idiopathic or inherited) or secondary to systemic disease, drugs or toxins. Primary forms of distal RTA have been linked to genetic variations of membrane transporters present in alpha-intercalated cells (Table II).3 In the exposed setting, the family history of lithiasis in all siblings is consistent with a dominant hereditary pattern and a genetic cause is most likely.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF SLC4A1 GENE?

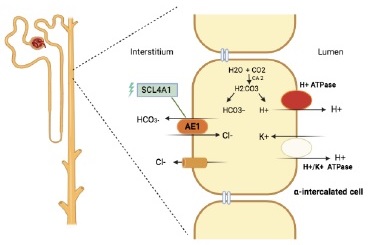

The SCL4A1 or AE1 gene codes for the anion exchanger 1 (AE1, also known as band 3), a chloride-bicarbonate exchanger that is cells in the distal nephron. AE1 is also expressed in erythroid cells.4

Rare genetic variants in this SCL4A1 have been associated with inherited forms of distal RTA (Table III)*4. The variant found in this family is a missense mutation in the 17q21.31, due to a single nucleotide variant cytosine to thymine (C>T) that results in substitution of serine amino acid by phenylalanine. This variant seems to distort the conformation of the putative anion binding site of the AE1. The lack of basolateral removal of HCO3- leads to intracellular alkalinization, thus inhibiting apical H+ secretion (Figure 2). In this particular variant, the expression of abnormal AE1 is limited to the kidney, leaving red blood cells unaffected.4-6

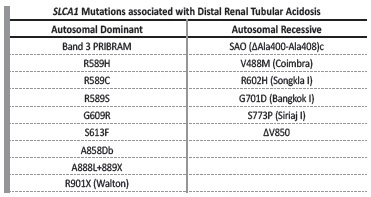

Table III SCL4A1 Mutations associated with Distal Renal Tubular Acidosis

Coexistence of Southeast Asian Ovalocytosis and dRTA results from compound heterozygous SLC4A1 SAO variant and another dRTA mutation in the opposite allele. Heterozygous G701D/(ΔAla400-Ala408) c, ΔV850/ΔV850, ΔV850/SAO; ΔV850/A858Db also result in dRTA. Adapted from: Yenchitsomanus PT et al. Molecular mechanisms of autosomal dominant and recessive distal renal tubular acidosis caused by SLC4A1 (AE1) mutations. J Mol Genet Med. 2005 Nov 16;1(2):49-62.4

Pathogenic variants of SLC4A1 have also been reported with autosomal recessive (AR) inheritance. The autosomal dominant (AD) forms of transmission are more common, present later in life, and are usually less severe than AR variants. In AD forms, incomplete RTA is often seen, similarly to our patient’s initial presentation, as opposed to AR forms, where complete distal RTA is always present. The AR form is more commonly associated with blood cell abnormalities, such as hereditary spherocytosis and Southeast Asian ovalocytosis.6,7

WHY NEPHROCALCINOSIS/LITHIASIS?

Distal RTA leads to a state of systemic metabolic acidosis, stimulating reabsorption of bone matrix and ongoing release of calcium alkali salts. Nephrocalcinosis and nephrolithiasis are a consequence of hypercalciuria and hypocitraturia in the presence of abnormally alkaline urine. Osteopenia in adults and osteomalacia in children are longterm consequences of this process. Hypercalciuria is also responsible for some degree of calcium-induced tubulointerstitial damage, and enhanced distal RTA.1,8

WHAT IS THE CAUSE OF CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE IN THIS PATIENT?

Although dRTA is usually associated to good renal prognosis provided that effective treatment is implemented, recent studies have demonstrated development of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) in long-term follow-up in a significant proportion of individuals with pathogenic variants (up to 31% in a cohort of 89 patients).9 In these patients, CKD seems to be the result of tubulo-interstitial damage due to persistente hypercalciúria, recurrent lithiasis, and hypokalemia when present.

Although the trend to CKD seems to be common, the same cannot be said for end stage kidney disease.10 Our patient’s disease course involved multiple episodes of obstructive calculi associated with urinary tract infections requiring urological intervention. Such recurrent renal injuries undoubtedly contributed to disease progression.

HOW SHOULD THESE PATIENTS BE MANAGED?

Long-term treatment includes sodium and potassium alkali administration. Administration of alkali in slightly greater amounts than that of daily acid production (around 1 to 2 mmol/kg/day) allows for correction of the acidosis. Potassium replacement should take place before acidosis is corrected to avoid further hypokalemia upon bicarbonate administration.1

The use of citrate allows for hypocitraturia correction and nephrocalcinosis prevention. In patients with lithiasis caused by dRTA, acidosis correction increases urinary citrate excretion, slows the rate of stone formation, and may even dissolve some of the existing stones. Most complications may be avoided with treatment of acidosis (with the exception of nefrocalcinosis once it is established).1,8

A prolonged-release formulation of potassium citrate and potassium bicarbonate (ADV7103) has recently become available to patients with distal RTA. It has shown to improve metabolic control, gastrointestinal safety and tolerance when compared to previous alkalinizing agents (especially those containing citrate).11,12

As outlined before, a significant number of patients with distal RTA will develop CKD and therefore it is important to maintain follow-up.

Early diagnosis, including genetic sequencing and treatment implementation, is paramount in the management of RTA. These actions will not only improve the outcomes of our patients, but also of their descendants. Our patient’s son and daughter were referred to our hereditary nephropathy consult and were found to have nephrolithiasis (Figure 3). Careful surveillance and routine testing will allow for early identification of dRTA and improved renal prognosis.

CASE DISCUSSION

Familiar history of nephrocalcinosis and nephrolithiasis in this case led to genetic testing. Diagnosis of dRTA is particularly challenging in the presence of autosomal dominant variants due to milder acidosis and later onset of disease in adult life. Lithiasis or nephrocalcinosis may be the first clinical presentation. Genetic studies are essential to determine risk of recurrence in following generations. Family screening allows early diagnosis and early initiation of conservative measures not only to halt nephrocalcinosis, but also delay or even avoid progression of renal impairment.