INTRODUCTION

Minimal change disease accounts for 10%-25% of nephrotic syndromes in adults.1 Spontaneous remissions are rare and often associated with secondary causes, the proteinuria ceasing once the trigger has been removed. In this case report, we aim to describe an odd clinical case of several early spontaneous remissions and relapses of nephrotic syndrome associated with minimal change disease in a cirrhotic patient.

CASE REPORT

A 47-year-old African descendent male with medical history of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection under antiretroviral therapy (ART) with emtricitabine, tenofovir alafenamide and dolutegravir, negative viral load and normal CD4+ count; and hepatitis B virus / hepatitis D virus (HBV / HDV) chronic co-infection, with Child-Pugh class B cirrhosis and negative viral loads as well. He had been previously treated for cutaneous and visceral Kaposi’s sarcoma, with liposomal doxorubicin, and had pulmonary and ganglionic tuberculosis, treated with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. He had regular follow-up in infectious diseases clinic.

The patient was admitted in the emergency department with abdominal pain and distension, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea progressively worsening for a few days. He had recently been taken nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) for lower back pain. Upon admission, he had hematemesis, which prompted an endoscopic exam, showing petechial lesions of the gastric mucosa and an inability to progress deeper into duodenum due to potential external constriction.

As a result, he proceeded to whole body computer tomography (CT) scan, that revealed extensive ascites and edema of small and large bowel walls (which would explain the constriction), and additionally, right pulmonary artery thromboembolism, right lower lobe pulmonary infarction, splenic infarction and left renal vein thrombosis. Transesophageal echocardiogram excluded vegetations or thrombi within the heart. He was treated with proton pump inhibitor and unfractionated heparin. During this period, the patient developed lower limb and scrotal edema. Due to increasing bilirubin, hypoalbuminemia (1.2 g/dL), high prothrombin time on admission (16.4 s) and increasing serum creatinine levels (SCr 1.32 mg/dL) it was initially admitted a chronic liver disease decompensation with subsequential hepatorenal syndrome.

Urinalysis then revealed albuminuria (3+) and hematuria (2+), with urinary protein/creatinine ratio (uPCR) 14 440 mg/g, thus leading to the investigation of an intrinsic nephropathy.

Ultrasound showed normal size, well-differentiated kidneys. HIV, HBV and HDV viral load were all negative, as well as hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies. Serum and urinary electrophoresis showed no monoclonal protein. Free light chains in serum were normal. Immunologic study, including complement C3 and C4 proteins, anti-nuclear (ANA), anti-double stranded DNA (dsDNA), anti-extractable nuclear antigen (ENA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic (ANCA) and phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2r) antibodies were all negative. Whole body CT-scan showed no signs of malignancy. Abdominal fat pad biopsy was Congo red-stain negative. Bone biopsy and myelogram were also performed, as the patient showed persistent pancytopenia, with no abnormalities.

The patient started perindopril 5 mg and IV furosemide, leading to progressive resolution of edema, ascites and proteinuria. He was discharged after 35 days, with SCr 0.82 mg/dL, uPCR 3891 mg/g and uACR 3173 mg/g, on perindopril 5 mg qd, spironolactone 100 mg qd, furosemide 40 mg qd, propranolol 40 mg qd and enoxaparin 1 mg/kg/bid (besides ART). A kidney biopsy was scheduled, but the patient abandoned follow-up after discharge.

Two years later, the patient was admitted to the emergency department, with anasarca. He had a mild elevation of transaminase (alanine aminotransferase 98 U/L and aspartate aminotransferase 133 U/L), normal bilirubin, severe hypoalbuminemia of 0.7 g/dL and acute kidney injury (SCr 2.7 mg/dL, urea 163 mg/dL) with oliguria. Paracentesis was performed, draining 5 liters of clear-yellowish fluid, with no evidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis on cytochemical analysis. Uranalysis revealed hematuria and a 24-hour urine collection had 37 g of proteinuria (mainly albumin). Once again, the patient was started on angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) and IV furosemide. On the following days, the edema, renal function and proteinuria normalized. By the time he was referred to a nephrologist, 1 month after the onset, he had no signs of kidney disease, therefore withholding a biopsy.

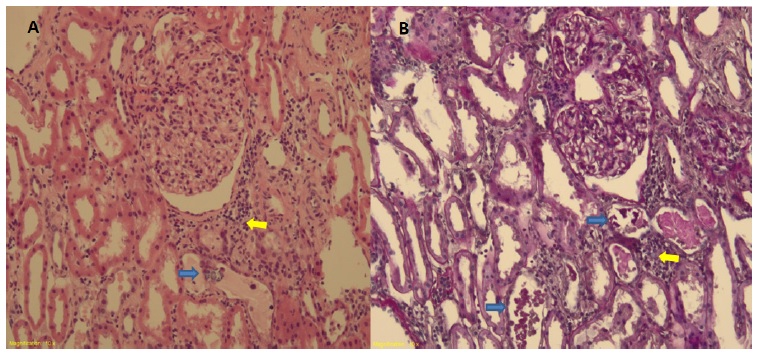

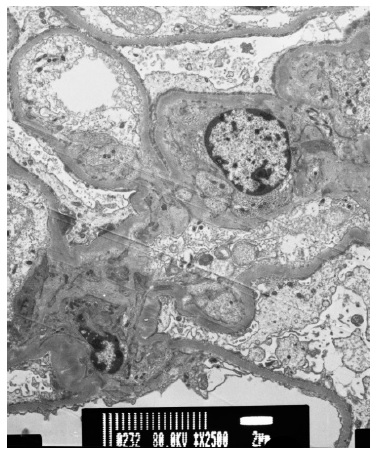

One year later, the patient had a third episode of nephrotic syndrome and was admitted in the nephrology department. He had serum albumin 1.6 g/dL, total cholesterol 288 mg/dL, uPCR 7180 mg/g and uACR 5478 mg/g. A kidney biopsy was performed and revealed: 23 glomeruli, 2 of which globally sclerotic; podocyte hyperplasia; few dilated tubules, with flattened epithelial cells, protein casts surrounding cell debris and microcalcifications; mild lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in the stroma between the altered tubules (Fig. 1); normal arteries; Congo red-stain negative; Immunofluorescence (IF) showed discrete, fine granular, mesangial IgM deposits. Electronic microscopy confirmed podocyte hyperplasia with foot process effacement in 80% of the basal membrane area, which was preserved and mildly thickened (Fig. 2). These findings were consistent with a podocytopathy (most probably minimal change disease) and acute tubulointerstitial nephritis.

Figure 1 Light microscopy stained by (A) hematoxylin-eosin x10 and (B) periodic acid-Schiff x10, showing normal glomerulus; acute tubular necrosis pattern with celular debris and protein casts and microcalcifications (blue arrows); peri-tubular stroma with mild lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (yellow arrow).

Figure 2 Electron microscopy (×2500) showing foot process effacement in at least 80% of the glomerular basement membrane area and absence of electron-dense deposits.

Due to previous early spontaneous remissions and clinical history of severe infections, including tuberculosis, we decided to withhold corticosteroid therapy. As predicted, 1 month after discharge, the patient showed again no signs of kidney disease: SCr 0.92 mg/dL, uPCR 75 mg/g, no hematuria and serum albumin 3.4 g/dL. We assumed that thromboembolic events diagnosed in the first hospitalization were due to nephrotic syndrome pro-thrombotic condition and, as the patient recovered with fairly normal serum albumin levels, anticoagulation therapy was suspended. To this day, the patient remains with no evidence of kidney disfunction.

DISCUSSION

Given the initial presentation of a cirrhotic patient with generalized edema and acute kidney injury (AKI), hepatorenal syndrome was considered at first. Hepatorenal syndrome is a serious condition, with poor prognosis, often associated with oliguric AKI, and no proteinuria.

Hence, once nephrotic syndrome was identified, it was clear that some glomerular barrier dysfunction was present. Abrupt onset nephrotic syndrome in an African-descendent patient poses primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) as the main hypothesis. The patient had HIV and HBV/HDV co-infection but he was being treated and had long time negative viral load, so collapsing FSGS or membranous nephropathy were weak hypothesis. The few reports of MCD associated with HIV and HBV infections, have been accounted as incidental, usually responding to anti-viral therapy, or immunosuppressive therapy in the set of relapsing disease.2,3Eventually secondary to tuberculosis, the patient could also have developed AA amyloidosis, but he was successfully treated for that condition, and Congo-red negative fat pad and kidney biopsy suggested that this was not the cause of the nephrotic syndrome.

The kidney biopsy finally confirmed a podocytopathy. Discrete unspecific IgM deposits on IF are common on MCD, which contrasts with the diffuse, global and intense mesangial deposits in IgM nephropathy (that may resemble MCD or FSGS on light microscopy).4-6Given the time from the initial presentation, the evolution with relapse-remitting pattern and no residual proteinuria or progressive worsening of renal function after those many years, minimal change disease was diagnosed.

Our patient also presented hematuria and AKI at each episode of nephrosis. Overall, AKI is an uncommon feature of MCD, but it has been reported in up to 34% of adult-onset disease.7 Also, our patient had cirrhosis, which further predisposes to AKI, due to effective arterial hypovolemia and inflammation. Hematuria is common in adultonset MCD, reaching 60% in some case series8 and it seems to be a benign condition.

Spontaneous remissions in MCD are rarely reported and usually happen months after the onset of nephrotic syndrome.9,10 There are reports of spontaneous remissions associated with acute viral infections11 and vaccines.12 On the other hand, some triggers have been consistently reported and deemed to induce secondary MCD, such as drugs, malignancies, infections and allergies.13 Our patient was under treatment with rifampicin and had taken NSAID at the first nephrotic syndrome episode; these drugs have been previously reported to be associated with MCD,14-16but both were discontinued shortly after.

He had no clinical evidence of acute infectious diseases and had no immunizations nearby none of the following nephrotic syndrome overt and remissions.

Once a patient had a spontaneous remission, relapsing is even less frequent.10This particular case we describe has several early spontaneous remissions and subsequent relapses, which kept us thinking about the underlying cause for the atypical MCD presentation.

The pathophysiology of MCD has been historically attributed to a circulating factor that alters glomerular membrane permeability.17,18 We hypothesize that, in the context of cirrhosis, the clearance of this molecules may be diminished and could contribute to the recurrence of MCD.

A more recent theory has focused on lymphocyte T dysfunction.19 There is evidence of overexpression of the co-stimulatory molecule CD80 in the podocytes of MCD patients, as well as low counts of circulating regulatory T cell (Treg).20 Though our patient had HIV infection, also characterized by T cell dysfunction, he was stable under ART, with undetectable viral load and CD4 count over 500 cells/mm3 throughout all 3 nephrotic events (lowest count 593 cells/mm3). There was also no evidence of lymphoproliferative disease.

Hemodynamic changes in renal perfusion in the context of decompensated chronic liver disease (such as intrabdominal hypertension; renal vascular vasoconstriction and venous hypertension) may interfere in the glomerular barrier function. Milani et al studied this hypothesis before, in order to determine the cause of frequently present albuminuria in cirrhotic patients.21

We also admit that a genetic background, as an unknown polymorphism related to podocyte function, could lay ground to the triggers mentioned above, and precipitate a nephrotic syndrome that resolves once the liver function resumes to its steady state. Being an African-descendent patient raises awareness on APOL1 high risk alleles (HR). Although its association with FSGS development and prognosis is well established on literature, the association with MCD is much less clear.22,23 Either way, APOL1 HR related disease has worse renal outcomes, with therapy resistance and progressive disease, which is contrary to our patient’s fairly benign course.

Trawalé et al. showed that up to 82% of cirrhotic patients may develop glomerulopathies, including IgA nephropathy, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and membranous glomerulopathy.24 There is one report of MCD associated with primary biliary cirrhosis,25 in a 36-year-old female with no evidence of advanced liver disease and evolving in steroiddependent pattern, differently from our patient.

In conclusion, this case represents an unprecedented report of a minimal change disease in cirrhotic patient presenting with several unexplained episodes of early spontaneous remission and posterior relapsing nephrotic syndrome.