Introduction

Due to population growth and industrialization, the increase in energy consumption has led to the exhaustion of the globe reserves of natural ES, since about 80% of the energy demand come from FF. The fact that these resources are limited highlights the need for RES. Furthermore, the use of FF harms human health and various forms of life existing in the environment, by causing air pollution and global warming 1-4.

Unquestionably, the global demand for more energy production, and environmental concerns are two of the most significant topics in the 21st century. In order to satisfy the world growing need for energy, at least 10 TW of C-free power needs to be produced by the mid of this century. Dramatic increase in petroleum price, FF limited reserves, stronger environmental concerns related to GHG emissions and global warming, and decay in overall human health and safety have reinforced the search for alternative ES. A significant part of the world total energy consumed is associated with transports, leading to the emission of harmful gases in the atmosphere, so the current transportation systems will no longer remain sustainable 4-6. There is a global effort to reduce GHG emissions associated with FF, since their use has a tremendous destructive environmental impact, such as climate change, O3 layer depletion, acidification and air pollution 3,7,8. To meet the challenges of climate change and depletion of natural ES, energy systems need to be sustainable, efficient, convenient and safe. Therefore, RES systems can play an increasing role in this context, and one of the most abundant of them is solar energy 1,9.

Over the past decades, the scientific literature on energy issues clearly shows that, due to severe environmental constraints, most of the power required for human activities should be provided by incident solar radiation, rather than by the air combustion of fossil HC, or nuclear reactions. This would prevent the deleterious impact of GHG emissions on the environment, and would also bring some additional benefits, such as the promotion of the nations’ energy independency, a reduction in the competition for access to oil resources, and could also contribute for solving the problems associated with the treatment and long-term storage of nuclear wastes, sustaining an ET 10,11.

The development of clean RES systems is of the utmost importance, for addressing the issues of climate change and higher global energy demands. With a rapidly growing world population, the global primary energy-consumption rate is expected to increase from 17 TWh, in 2010, to 27 TWh, by 2040. RES, such as solar, wind and wave energy, are intermittent and often location specific. These constraints require efficient means for storage and transportation of excess energy produced at peak times, to be reintroduced into the grid where, when and as required. This excess energy is best stored in a form that is transportable and clean 12.

Due to its intermittent nature, the endeavour of implementing such an ET on a large scale, and turning sunlight into renewable EE, needs an easy and affordable way to transport and store it. The ET will rely on the development of storage technical solutions, at different time and size scales. From a practical viewpoint, it is necessary to develop an efficient energy infrastructure, adapted to the location and time intermittent nature of earth-incident sun light radiations, and which meets consumers’ demand. For technical and cost reasons, electrochemical (batteries) and gravitational storage (e.g. via pumped hydro-resources) cannot satisfy these needs. A universal chemical energy carrier that may be used for RES storage, transportation and distribution, and also for re-electrification, by electrochemical means or chemical combustion in air, and that could be a fuel for domestic, energy and transport sectors, is required 1,5,10,11.

H2 has been proposed as the best fuel for this future energy system. Previous studies suggested that H2, as an ES, may be much cleaner and far less expensive. There are many reasons to build a H2 economy, and although there are risks and costs involved, they are far less critical than the long-range risks of a HC economy. Moreover, H2 combustion has many environmental benefits. It could replace FF, by reducing CO2 emissions, and join electricity as an important energy carrier. Presently, H2 and FC technologies provide a major opportunity of producing a green revolution in transportation, by completely removing CO2 emissions. Previous work has identified challenges facing these technologies, which must be overcome, in order to improve the efficiency of the energy production process. H2 can be produced from conventional sources (coal, petroleum and natural gas), through methane reforming, organic wastes and biomass, or from RES (including hydroelectric and wind power systems, PV energy conversion, etc.) through WEL. Several studies have been published about H2 production from RES. Hence, H2 will be a key player in the storage of these RES in the near future 1,8,13.

H2 is the most abundant element in the universe, and possesses a higher heating value than other fuels under the same conditions. On Earth, H2 is not found in its free form, but in combination with other chemical elements, such as in water and natural gas. Therefore, it may be produced by several processes, such as electrolysis, gasification or thermochemical splitting. Approxim. 50% of global H2 production is currently obtained by natural gas steam reforming, around 48% from other FF (30% from oil/naphtha reforming, 18% from coal gasification), 3.9% from electrolysis and 0.1% from other processes. H2 is widely used in various industries, such as petrochemical and petroleum refining processes, fertilizers, fuel cell stacks and electric vehicles 2,14-17. Despite the growing interest in H2 as an energy carrier, its main uses continue to be in petroleum refining, ammonia production, metal refining and electronics manufacturing, with an average worldwide consumption of about 40 million tonnes. This large-scale H2 consumption thus requires large-scale production 5,13,18. At present, H2 represents a market of roughly fifty billion US$, for 40 million tonnes annual production. The prospects of future population growth, with the consequence of an increased requirement of food and various commodities, lead to the logical conclusion that H2 demand will also increase, nonetheless to satisfy the needs of conventional transportation fuels, fertilizers and chemicals 17.

Gaseous H2 of electrolytic grade has been considered, for many decades, to be such a game-changing energy carrier. This is a by-product of brine electrolysis, but it can also be obtained, in an efficient and affordable way, through WEL, while the Earth's atmosphere can be used as an O2 reservoir of infinite capacity. Commercial WEL are found in quite varied fields in industry, but, so far, the technology has been mainly used for stationary production, in view of chemical applications. Regarding energy applications, existing plants of limited size are only available on a demonstration scale. Future WEL will have to be customized, in order to allow non-stationary modes of operation. Therefore, efforts are currently being made to develop hundred-MW scale systems 10.

In recent years, H2 has increasingly become an alternative energy carrier in the power and automotive sectors, due to its renewable, transportable and emission-free properties 7, 819. Moreover, by using FC, H2 can be converted into EE, and continuously operated under H2 and O2. Unlike FF, H2 is not freely available in nature as a primary fuel. This means that it must first be produced from its sources, such as natural gas or water, and then used as an ES. Taking the current environmental and energy issues into account, WEL can be an efficient, clean and promising alternative technology for H2 production. This technique could be well integrated with the available RES (such as solar, wind or hydro power). The major limitation of large-scale WEL for H2 mass production is the rather high overpotential required for the reactions. This overpotential plus the ohmic losses in the electrolysis process make the actual potential to exceed the standard WEL 1.23 V, reaching values from around 1.8 to 2.0 V 13,19. In addition to pure H2 production, recent studies showed that power to gas and power to liquid/fuel technologies are also feasible to convert H2 produced from WEL into useful products, such as methane, methanol, dimethyl ether, etc. via surplus EE from wind turbine or solar cells 15.

In terms of sustainability and environmental impact, PEM WEL is considered one of the most promising techniques for high pure efficient H2 production from RES, since it only emits O2 as by-product, without any C emissions. Furthermore, the produced H2 and O2 can be directly used for FC and industrial applications. However, overall WS results in only 4% of global industrial H2 being produced by WEL, mainly due to economic issues. Nowadays, the need for green H2 production has increased the interest on PEM WEL. So, there is considerable research on the development of cost effective electrocatalysts for PEM WEL 13.

Another way to improve H2 environmental-friendly production is the design of new AWEL, in order to optimize their combination with RES 4. H2 production via WEL processes, using wind energy, is currently adjudged one of the H2 pathways with the lowest life cycle GHG emissions, with competitive production costs 8. The development of clean power sources and the reduction of GHG emissions have led to many investigations on low temperature FC, such as the PEM FC, fed either with pure H2 or with other fuels, particularly, low weight liquid organic compounds, such as formic acid, methanol or ethanol 6.

Most human and industrial activities lead to enormous WW generation. The majority of WW is untreated, when routed for disposal in the environment, due to a lack of strict regulations in many developing countries 20. This causes a detrimental impact on human health, economic productivity, freshwater resource quality and the ecosystem. Most of generated WW include domestic residence, commercial properties, industrial operations and agriculture. Hence, WW management has to be done by means of safe and effective collection methods. WW treatment and returning treated water back into the environment could have a lower impact on the environment and ecosystem. Furthermore, WW is a valuable resource, which is most suitable for generating cost-effective and worthwhile sustainable ES, nutrients, organic matter and other useful by-products 21,22.

In addition to this introduction, this paper consists of the following topics: the most relevant aspects about H2 production; RES; WWEL issues; integration and related work; and finally, the main conclusions.

H2 production

Due to its highest gravimetric energy density, H2 has been regarded as the preferred clean-energy carrier, with potentially environmentally-friendly production through the solar-assisted WS 23,24. Indeed, H2 produced from water, using renewably produced electricity, via electrocatalysis, or by direct conversion of solar energy, via photo catalysis or photoelectrochemistry, offers a zero emission fuel 5,12. An alternative approach is to use molecular H2 as an ES and carrier, which strongly reduces GHG emissions, depending on the primary sources used for its production. With RES, such as nuclear, hydroelectric, wind, solar and tidal power, H2 production by WEL is the most developed process, leading to high pure H2, suitable to feed low temperature FC 6.

The inherent dependence of RES on weather conditions causes them to be intermittent. In this context, H2 offers a promising solution, since it can be produced from electricity generated by RES, and then stored and/or transported. In addition, it could provide a sustainable fuel for transports, portable applications and power supplies to electronic devices. Moreover, H2 production could also be an attractive option for remote areas, such as islands, without access to the primary grid, and an economic alternative in countries with a large RES base, but lacking FF. H2, obtained by the RES-H2 combination, using electrolysis, is probably one of the most environmental friendly strategies. For this reason, in the past decades, great attention on the RES-H2 interaction has been paid by energy companies, so that they can position themselves in the future markets of distributed power generation and alternative fuels 4.

Due to fluctuations in RES production and consumption rates, buffers for energy storage, such as EECS systems, are required. The most promising EECS systems are redox flow cells, regenerative FC, electrochemical conversion of CO2 (and water or H2) into FF (e.g. formic acid) and electrochemical capacitors. H2 annual consumption increases 6% per year. Today, it is mainly produced from FF, mostly natural gas reforming and coal gasification methods 25, which result in high CO2 emissions, and their efficiency is approximately 70-75% and 45-65%, respectively. A small percentage of H2 (about 4%) is produced by WEL, which consumes huge amounts of energy (6-7 kWh per m3 of H2) 26.

When compared to other available methods, WEL has the advantage of producing extremely pure H2, ideal for some high value-added processes, and often found in sectors, such as marine, rocket, spacecraft, electronic and food industries, as well as medical applications 5,18. Large amounts of pure H2 (99.999 vol%) can be produced using WEL, without emissions of gaseous pollutants. The main research on H2 energy now focuses on the development of energy-efficient WEL systems (electrode materials, electrolytes, separators, etc.), which are durable, safe and effective storage methods, required due to the H2 low volumetric energy density 1,6,13,18,25.

The WS reactions (Eq. (1)) are endothermic and, therefore, require energy that can be provided by an electric current through a suitable electrochemical cell.

Although it seems simple, electrochemical WS requires a detailed understanding of the anodic and cathodic mechanisms, in order to achieve high rates and minimum EE input values.

HER, on different metals, in acidic or alkaline media, is one of the most investigated reactions in the electrochemistry field. HER has received considerable attention, because it supplies highly pure H2, which is an interesting candidate as an energy carrier for future FC applications, and one of the main reaction products during chlorine production. HER is the main reaction developed in AWEL, H2-based FC, and during some industrial productions, such as chlor-alkali and chlorate cells. However, these electrochemical processes consume large amounts of EE, due to H2 overvoltage. Hence, cathodic overvoltage reduction is of great interest, so as to minimize energy consumption. The properties of an ideal electrocatalytic cathode are: low H2 overvoltage at industrial j; no potential drift with time; good chemical and electrochemical stability; long lifetime and no release of process-deleterious products; high adhesion to the support; low sensitivity to impurities poisoning; low sensitivity to current shut down (short-circuit) or modulation; no safety or environmental problems in the manufacture process; and easiness of preparation at a low cost/lifetime ratio. Therefore, choosing the most appropriate electrode material is not an easy task 27.

The ideal thermodynamic voltage required to drive WS is 1.23 V, at 298 K and 1 Atm. However, in practice, due to losses, kinetic barriers and non-idealities in the catalysts, larger voltages are required. The difference between the thermodynamic and the applied potential is known as overpotential, which has contributions arising from activation barriers at the anode and cathode surfaces, among other considerations. This renders HER and, particularly, OER, sluggish, so that they necessitate catalysts to reduce the anodic and cathodic activation barriers, and increase the reaction rates 12.

Pt HER exchange current is, at least, two orders of magnitude higher in acid than in alkaline electrolytes. Pt is commonly used as cathodic catalyst, because of its low overpotential and excellent activity for electrocatalytic HER. However, the high cost and the easiness of chemical poisoning restrict its application. On the other hand, OER may occur through various pathways and adsorbed intermediates. RuO2 and IrO2, alone or in combination, are often considered the reference OER catalysts, but neither is ideal. The OER reaction reverse is ORR, where molecular O2 is reduced to water. ORR involves the same intermediates as OER, and is most conveniently carried out in an alkaline environment, where catalysts that are more active and stable than in acid are available. Therefore, it remains a challenge to generate catalysts (beyond Pt, Ir and Ru) for both HER and OER, which can exhibit selectivity, remain stable over time, and be produced in large quantities, using low-cost methods. To reduce WEL costs, substantial efforts have been made to develop catalysts, such as non-noble metals and non-metallic materials. Since the low abundance of high-activity Pt-based materials hinders their large-scale application, more cost-effective and earth-abundant catalysts, with long-term stability, are needed for HER. To meet the demand, a variety of transition metal-based catalysts, including their corresponding single atomics (i.e. Cu, Au, Mo, Pd, Rh, Fe, Ni and Ti), alloys (i.e. steel), nitrides, phosphides, carbides, selenides, sulphides, tellurides and chalcogenides (particularly, layered transition metal dichalcogenides containing S or Se) have been proposed. Examples are ternary metal phosphides (in particular, of Co and Mo) 1,12,13,23,24,27-38. For example, MoS2 is a promising catalyst for HER, because its H2 adsorption energy and exchange j are close to those of Pt 34. Other examples are Co-Ni-M ceric oxide/nitrogen fluoride (M dopant material = O, S, P and Se) grown on porous Ni foam 39 and V, and N co-doped CoP nanoleaf arrays 40.

In order to further reduce the cost of HER catalysts produced by using C-supported electrocatalysts, especially those only consisting of earth abundant low cost materials, such as aniline-C, Mo2C/CNT, Ni2P/CNT, co-doped FeS2/CNT, WO2/C nanowires and CoFe nanoalloys encapsulated in N-doped graphene, potential HER electrocatalysts, as alternatives to Pt, have been extensively studied. Regarding OER in PEM WEL, significant research efforts have focused on reducing the noble metals content by mixing transition metal oxides with IrO2 and/or RuO2, such as TiO2, SnO2, Ta2O5, Nb2O5, Sb2O5, PbO2, MnO2 and other mixed oxides 13,41. Co3O4 films have been found to be catalytically efficient and stable for WS reaction in an alkaline aqueous solution monolithic PV-electrolysis system 9. Raney 2.0 Ni-coating was analysed using various electrochemical techniques, in order to assess its absolute performance, and it was confirmed to have an extremely low overpotential for HER. It was also confirmed to be an acceptable catalyst for OER, making it the highest performing simple bifunctional electrocatalyst known 42. AWEL, using binary alloys with additives elements (Fe, Cu, Co, and Cr) as electrodes for the cathode, was studied. The results showed that the elaborated Zn and Cr cathodes produce more H2 gas 1.

WEL could be carried out in different types of electrolytic systems, such as AWEL, PEM electrolysers and SOEL. However, the use of costly materials (precious metals) in PEM or SOEL fabrication, along with their shorter lifetime, makes them relatively more expensive than the alkaline cells for small-scale H2 production systems. The current commercialized AWEL mainly use NaOH or KOH aqueous solutions, as the state-of-the-art electrolytes. AWEL have the advantages of convenient construction and operation at high pressure, but they have relatively low j values and efficiency, due to low operating temperature, requiring a high-cost maintenance, because of the electrolyte solution membrane corrosion. Although AWEL is inherently low-cost and independent from noble metals, the development of large-scale H2 production systems based on this technology still needs potential improvements in the overall cell efficiency, through energy consumption decrease, and increase in the electrolyte ionic conductivity 15,16,19,36,43,44. Commercialized WEL (mostly alkaline technology) are found in quite various industry fields, but, up to now, the equipment has been mainly utilized in stationary production for chemical applications 2,11.

In contrast, PEM has high j values and efficiency, and it can be operated at a higher pressure than that of AWEL, in order to avoid the use of compressors to pressurize produced H2. However, the catalysts and membrane materials are expensive, and the system is complex, due to high operating temperature and water purity requirements. SOEL under development can be operated at a high temperature, because of the usage of thermally stable solid oxides, and have high conversion efficiency and low EE consumption 2,15. Water must be desalinated and demineralized before electrolysis. PEM electrolysers are more sensitive to water purity. If saline water (brine) is fed into a regular electrolyser, it is quite likely that ionic chlorine is evolved at the cathode, rather than O2. A method to generate H2, and desalinate sea water through electrolysis, is to surround electrodes by ions selective membranes that have the role to stop side reactions (such as toxic chlorine evolution, which should be avoided). Using Mg as the anode catalyst also promotes O2 evolution, in the detriment of chlorine formation 17. AWEL is accomplished by the application of, at least, 1.229 V through two electrodes immersed in an alkaline solution. The voltage value is influenced by several factors, such as temperature, pressure, electrolyte quality and composition, and space between the electrodes. Therefore, a greater applied potential, in order to overcome these factors, should be required 1. Another parameter influencing the metals alloys stability is the alkaline solution concentration. In general, HER rate is reduced with the increase in the alkaline solutions concentration, due to the competition between H2O and OH adsorbed onto the electrode surface. The increase in concentration results in a higher viscosity, followed by a decrease in the ion activity, which is harmful for the ionic transfer into the solution 27.

On the other hand, the incompatible configuration of electrocatalysts for HER and OER, in the same electrolyte, usually leads to an overall inferior WS performance. Therefore, the fabrication of highly active bifunctional electrocatalysts, for both HER and OER, in the same electrolyte, is extremely crucial, in order to promote overall WS, and simplify the electrolytic device configurations. Transition metal chalcogenides have been regarded as one of the most promising bifunctional electrocatalysts in alkaline media, for overall WS, in virtue of their ideal intrinsic properties. A self-standing dual-metal Se electrode (Co0.9Fe0.1-Se/NF), synthesized through an easy one-step electrochemical deposition method, was employed as a bifunctional catalyst in overall WS. When simultaneously served as anode and cathode for AWEL, it only requires 1.55 V for overall water electrocatalysis, at a j value of 10 mA/cm2, which outperforms many state-of-the-art functional electrocatalysts, possibly allowing the design of highly efficient and cost-effective bifunctional catalytic materials, for green RE applications 35.

The conventional AWEL typically operate on cell potentials near 2 V, with a system efficiency close to 60%, and have demonstrated lifetimes exceeding 10 years. Commercialized PEM electrolysers are available in smaller sizes than those of AWEL, with a lifetime of 5 or more years, which results in an increased efficiency, but decreased durability, when temperature rises. Furthermore, increased catalyst loading would raise the device costs. The main disadvantages of PEM WEL are the noble metals high prices, the system complexity, scaling up difficulties, and the membrane great costs 28.

AEM WEL is a H2 production method that uses EE. It aims to combine AWEL low cost with PEM electrolysers advantages. One of the major strengths of AEM WEL is the replacement of conventional noble metal electrocatalysts with low cost transition metal catalysts. AEM electrolysis is still a developing technology 16,37.

Nowadays, there is an incentive to improve AWEL over system scales larger than PEM electrolysis. This can be achieved in several ways: selecting better HER-OER catalysts; using system components and architectures that allow operation at high temperatures, and reduce system complexity, capital and operating costs; and using an AEM in place of an electrolyte, which results in a compact system, free of bubble effects, such as a PEM device that offers a large choice of non-Pt group metals catalysts with low resistance and high stability 28.

Another alternative is the electrocatalytic oxidation of low weight oxygenated compounds, such as formic acid and methanol, which has been the subject of many investigations, for nearly fifty years, to be used in a direct oxidation FC or in clean H2 production, by their electrochemical reforming in an EC. The electrochemical reforming consists in the electrocatalytic oxidation of compounds containing H2, at the PEM EC anodic side, which can produce very pure gaseous H2, by reducing, at the cathodic side, the protons that cross-over the membrane. More importantly, this process can occur under mild experimental conditions, such as ambient temperature and pressure. Several organic compounds can be considered as H2 sources, such as carboxylic acids, alcohols, sugars, e.g., formic acid, methanol, ethanol, glycerol and glucose. Although the electrochemical decomposition reaction of these compounds displays a low cell voltage (under standard conditions), larger cell voltages usually occur under special working conditions, due to the high anodic overvoltages encountered in their ECO 6.

Substantial research efforts have been devoted to co-electrolysis with small molecules and water. Therefore, the cathode could produce H2 with less energy consumption than that of overall WS, when these electro-oxide reactions replace OER at the anode. For example, water/aniline co-electrolysis reaction, with C paper as the anode, which produces value-added polyaniline and H2, compared to traditional WEL, showed that the entire co-electrolysis overpotential is significantly reduced 45.

Significant R&D efforts and investments will be needed, before a H2 economy becomes reality, since the financial, societal and political efforts to insert it into the world economy is considerable. Currently, many associations exist to promote H2 economy concept, at all levels of society, and several governments are committed to putting efforts towards its development. The ET main problem is not the concept itself, but the time it will take for a large-scale implementation. Future WEL will have to be customized, in order to allow non-stationary operation modes. PEM WEL are commercially available at the multi-MW scale, and have already demonstrated their ability to operate under transient power loads. This is why efforts are currently being made to develop hundred-MW scale systems 11,17.

RES

The global overall energy consumption is six times higher than in 1950, and is expected to increase by as much as 55%, by 2030, due to population growth and higher living standards. In addition, water resources have been diminishing. Renewable internal freshwater resources have decreased about 40% in the past fifty years. These numbers are expected to aggravate in the future. Hence, it is of the utmost importance drawing more attention to the sustainable development of water treatment and ES systems, in order to tackle the issue of energy and water scarcity. Systems based on RES can be part of the solution, if they are combined with another ones, due to their intermittent nature 14.

FF (oil, coal and gas), hydro and nuclear power, and RES (e.g. solar and wind) contributions to global energy demand are approxim. 86, 4.43, 6.8 and 2.77%, respectively. Today, more than 70% of EE is generated from FF. In fact, FF burning in recent decades has caused serious environmental problems, with a huge impact on climate change and global warming. Concerns about FF global CO2 emissions and increasing costs are motivating the development of technologies for production from RES, such as wind, solar and H2 energy systems 17,25.

At present, direct sunlight is potentially the most powerful RES. In less than an hour, the Earth receives the same amount of energy from the sun which is globally used by mankind, in a year. In contrast to most of the other technologies, solar energy is only limited by the conversion costs and intermittency in time. Sunlight can be used through a wide variety of technologies that apply the physical principles of energy conversion. These various technologies deliver energy in different forms: electricity, high- or low-quality heat and synthesized fuels, such as H2 and HC. This means that there are several possibilities as to where and how each conversion option is best applied. PV systems are a renewable and sustainable option for providing EE, due to the almost universality of solar resources, and the systems easy operation, compared with other ES 46.

The use of RES, such as wind and sun, requires the simultaneous use of effective energy storage systems, due to their intermittency and unpredictability. The most reliable storage systems currently under investigation are batteries and electrochemical cells for H2 production from WS. Both systems store chemical energy that can be converted on demand. Consequently, EE storage has been recognized as one of the most promising approaches to an increase in grid efficiency, voltage stability and reliability, especially in order to optimize power flows and support RES production 36.

Despite that most RES systems are known as good solutions for producing green energy, they require different structures that generate distinct energy costs and CO2 emissions 47. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the appropriate structure for RES systems to achieve energy sustainability. In the last decade, DER gained more attention and interest from governments, because they are more flexible and have a low CO2 emission. PV systems are one of the most representative DER, being widely used in power generation 48,49.

PV systems are expected to grow significantly as global ET towards RES. By mid-century, they will supply a large portion of the world energy needs, beyond the power sector, as the result of new EE-to-fuel technologies. Most of these technologies involve the production of renewable H2 from intermittent electricity RES 50. H2 production, based on an energy mix through a system using a MHP and a PV system, has been evaluated by a study. The supply of EE to a WEL is the purpose of a MHP complementary to the PV system, as the latter is an intermittent power source, and only works with sunlight. The study has shown its technical and economic viability 50.

Additionally, combined PV/thermal systems that simultaneously produce EE and hot water can be considered for H2 production, leading to higher electrical efficiency and extended service life 51.

H2 importance for stopping environmental damages generated by FF combustion has been pointed out since the beginning of this energy concept development. The main pollutants from FF combustion are CO2, CO, SO₂, Ni oxides, O3, lead, soot and ash. These compounds negatively affect humans, through water resources, farm produces, plants, forests, animals and other components of human habitat, such as buildings (facades degradation, due to pollution), coastlines and beaches (damaging through oil spills), and contribute to climate changes (associated temperature rise, ice melting and ocean waters rising level) 17.

Green methods for H2 production can be obtained from electrical, photo-electric, photonic, thermal, photo-/electro-thermal, bio-/photo-chemical and thermal-biochemical sources, which can be derived from RES, nuclear power and energy recovery processes (landfill gas and industrial heat). Green H2 production technologies are not presently available with reasonable efficiency and costs. There is one green H2 production method that can be considered as a reference, and performed with off-the-shelf components, namely, PV-electrolysis, which couples a PV power generation system with a WEL. Other methods involve the use of one or more green ES, for generating H2, directly or indirectly. The materials from which H2 can be extracted through green methods are water, brine (sea water), hydrogen sulphide and biomass 17.

Regarding green H2 production methods combined with WEL there are: PV systems, geothermal, wind, nuclear, hydric or tidal power sources; concentrated solar power; ocean thermal energy conversion; biomass gasification; and coal gasification coupled with C capture and storage. Photonic H2 generation methods present a considerable interest, since they are essentially green. Water photolysis can be done through photo-, bio-, or catalytic electrolysis. Biological methods to generate H2 include direct and indirect photolysis, photo-fermentation and dark fermentation. Catalytic production methods from biomass include gasification, pyrolysis and sugars conversion into H217.

WWEL

Industrialization demands high water and energy consumption, generating large amounts of WW, of which treatment, along with RES generation, is an ideal way for tackling these problems 7,10.

Recently, H2 production from WW has gained attention as an emergent technology. Green H2 generation can be achieved by various methods, such as dark/photo fermentation, bio photolysis and microbial electrolysis 52-54. Using raw industrial WW for H2 production can be a high energy-intensive and low-yield process. This is because raw industrial WW consists of complex and recalcitrant biodegradable compounds that hinder H2 yield and production rate. Hence, to enhance the process feasibility and sustainability, pre-treatment methods, such as physical, chemical, biological and mechanical ones, can be incorporated as an additional step. The pre-treatment process accelerates WW H2 generation capacity and yield. In addition, for more environmentally benign outcomes, the sun energy can be utilized as power source for hybrid solar thermal and integrated photo electrochemical systems. In this vein, many studies focus on systems that can produce H2, and treat WW in situ7,3,14.

Several processes can be used for industrial WW treatment, such as biological, adsorption, advanced oxidation, chemical and ETCG, and membrane separation processes. ETCG treatment processes have been widely applied in different conditions, for removing organic and inorganic pollutants from WW effluents. They are currently attractive, especially in view of the several research efforts that are aimed at C capture and pollutants mitigation. These pollutants include heavy metal ions, total suspended solids, colloidal materials, microorganisms and many other contaminants, such as total dissolved solids, phosphorus, mine effluents, COD, biochemical O2 demand, lignin, dyes, phenols from OM WW and anionic contaminants 55.

Electroplating, metal plating, leachate or acid mining WW contain various toxic substances, such as solvents, oil, volatile organic compounds and metals. Metals such as Cu, Ni, Cr and Zn are harmful, due to their toxicity effect on surface or ground water, if they are discharged without treatment. ETCG can be quite effective in treating these industrial effluents. This process comprises metallic cations generation, which occurs at the anode, and H2 production, which takes place at the cathode 3.

Electrochemical methods are used to remove various pollutant organic and inorganic species from WW. Using electrochemical methods for organic effluents treatment has more advantages than biological or chemical techniques, such as versatility, environmental compatibility and potential cost effectiveness, among others. Both direct and mediated ECO can be considered, and have proved to be interesting methods for different research groups and industries seeking new technologies for WW treatment 10,56. Electrochemical technologies have gained importance around the world, for the last two decades. There are different companies supplying facilities for metal recovery, water treatment for drinking, and WW from tannery, electroplating, dairy, textile processing, oil and oil-in-water emulsions, etc. 56.

ECO is performed by the action of strong oxidants, similar to chemical destruction, but the in situ EE generation provides better efficiency for the organic substrates abatement. Direct electrochemical destruction has been investigated with particular focus, since the end of 1980s, through the testing of different anodic materials for the oxidation of diverse organic pollutants dissolved in water. On the other hand, indirect oxidation (also called mediated ECO) is based on strongly oxidant species activity, and may also represent an interesting alternative to the aforementioned WW treatments 46,56. There are direct and indirect (mediated) processes. The latter group includes active chlorine, O3-mediated attacks and others, where the main reaction stages take place in the solution bulk. The former group would include those processes of which main stages occur at the electrode surface, through reactants and intermediates adsorption, the strong oxidant being essentially the hydroxyl radical. In investigations on direct and indirect oxidations, many organic substrates, as well as different experimental conditions and anode materials, have been considered. Nevertheless, in many cases, the electrochemical process leads to the formation of stable carboxylic acids, such as maleic, formic, acetic, malonic and oxalic acids. These molecules may represent the polluting content of industrial WW, e.g., in oil manufacturing 56.

Different advanced oxidation processes have been developed and investigated by several research groups, for organic pollutants removal from WW, such as Fenton’s processes, photo-assisted Fenton´s processes, UV/Fe3+-oxalate/H2O2, photocatalysis, O3 water system, Mn2+/oxalic acid, H2O2 photolysis, O3/UV and others 56,57.

In this context, water-treatment technologies based on advanced ECO processes are more effective. This is due to the action of highly reactive O2 species, such as *OH hydroxyl radical, in the reaction mechanism, usually based on anodic oxidation or Fenton's reaction. Anodic oxidation combines high efficacy and simplicity, favouring organic substances oxidative destruction in water, through the direct action of *OH formed at the anode surface, by water oxidation via the process in the following equation:

Anodic oxidation ability depends on the selected anode, and a wide variety of electrode materials have been investigated 10,56. For example, dairy WW treatment was performed by the electro-Fenton’s process 58. ETCG was investigated for the treatment of agro-industry WW 59 and of swine manure effluents 60. In addition, many studies have shown that ETCG can efficiently treat effluents containing metal ions, such as As, Ni, Cr, Cd+2, B and steel slag. A novel approach, which integrates ETCG with one or more treatment processes, has been recently practiced, improving colloidal and non-biodegradable pollutants removal. Several treatment processes, including adsorption, chemical coagulation, magnetic field, reverse osmosis and membrane filtration, have been combined with ETCG, in order to improve pollutants removal efficiency. The investigated pollutants were several, such as methylene blue, malachite green and remazol yellow (derived of synthetic solutions from a solar-powered treatment system), RB5 and RB19, Cu(II) ions, lightweight oil recovery, organic and inorganic materials from seawater, fluoride ion from freshwater, glyphosate from aqueous solutions, hydraulic fracturing produced water, highly polluted industrial, cardboard paper mill and paint manufacturing effluents, landfill leachates, steam-assisted gravity drainage, and Cr(VI) from simulated WW. The pollutants also included antibiotics, car wash, dye, medical, offset printing, oils, slaughterhouse and textile WW 55. Electrochemical treatment using thin-film diamond electrodes has been applied in industrial WW where highly toxic organic compounds were present. This proves that WW treatment, H2 production and waste heat recovery can be carried out in a single electrochemical processing device 61.

Despite all the advantages of electrochemical methods, they have a relatively high electric potential (around 2 V) requirement that limits their applications. EE consumption during the process can be reduced by using semiconductor-based photoelectrodes. The reaction starts as the photons reach the photocatalytic surface and are absorbed, as a result of electron-hole pairs. In that process, the formed electrons vast amount of power allows them to reduce some metals, and generate dissolved O2 in a superoxide radical ion form. The remaining electron holes can oxidize adsorbed water into hydroxyl radicals that are highly reactive and widely used in water treatment applications 14.

Electrochemical reactions that produce molecular H2 via WS can degrade organic contaminants in WW, which enhances H2 generation 62. Selected organic compounds electro-oxidation was investigated, in order to determine optimal process conditions towards H2 production from potential WW sources 63. Organic WW photo-degradation and simultaneous HER were studied, using the photo-Fenton’s reaction 64,65. Black liquor electrolysis, used to perform HER, was found to be kinetically more favourable than AWEL 66. MoSx was used as an electrocatalyst for HER in real acidic WW 67. Wine industry waste was also studied in a low-temperature PEM EC 68. Landfill leachates electrohydrolysis was proven to be an effective method for H2 gas production, with the simultaneous removal of: COD 69; OM 70,71, vinegar 72, domestic matter 74-76, swine 77, chicken 78, cheese whey 79 and sugar industries 80 WW; and of organic wastes with proteins, polysaccharides, volatile fatty acids, salts and metals, such as peach pulp, food wastes, leachate and anaerobic sludge 3.

One different approach is to directly electrolyse biomass wastes 79,81. Electrohydrolysis or ETCG can also produce H2 gas from metal-plating WW 3. Antioxidants containing protein-based metal-free organic catalysts were used for H2 production by noodle WWEL 82.

Another way to reduce the energy requirement in the WS process is the replacement of anodic OER. Replacing OER with Fe oxidization in the anode, via the Fenton’s-like process, is one of these methods. It is possible to have a 69% decrease in the required energy for the anodic electrochemical reaction, which can be compared to OER. A reactor of which energy is supplied to the electrolysis from a PV array was developed, combining H2 production and electro-Fenton’s oxidization process in an electrolyser. This new hybrid configuration combines an electrolysis process with three different photo-assisted advanced oxidation processes, such as UV/Fenton’s, UV/TiO2 and UV/H2O2, which increased H2 gas production rate, and treated RB5 synthetic textile WW. RB5 and sucrose were dissolved in water, for simulating the textile and food industry WW, respectively. Photo electro-Fenton’s reaction appears to be a desirable option amongst the existing H2 production and WW treatment systems 14.

MEC is a promising technology for dyes degradation. Besides, H2 could be recovered from MEC fed with organic matters, WW or other RES, with less EE consumption than that of WEL 34.

The latest development in AWEL is APWEL, which employs a solid polymer electrolyte based on AEM. Such a design has the advantage of low gas cross-over, higher flexibility, and suitability for scale-up and operability at high pressure, providing a simplified lower cost system. A novel approach combines reverse electrodialysis and APWEL for renewable H2 production. APWEL is powered by salinity gradient power extracted from sulphate rich industrial WW, as a non-intermittent power source 83.

Integration and related works

Hydrogenization, as a crucial smart energy solution, in order to achieve a sustainable future, has potential benefits, such as: large scale and efficient RES incorporation; integration within smart grids; worldwide RES use across sectors and regions; enhanced energy systems resilience; decarbonized energy use; and feedstock for many industries. R&D on H2 and power generation from an intermittent RES, such as wind and solar energy, has been carried out in recent years 84.

WEL works well at a small scale, and the process is even more sustainable if the EE used is derived from RES (wind, solar and hydric energy, etc.). In a conceptual energy system involving production, conversion, storage and use, in remote communities, WEL may play an important role. When abundant RES are available, extra energy may be stored, in the form of H2, using WEL. The stored H2 can then be used in FC to generate EE, used as a fuel gas for heating applications, and transported to other places where RES are unavailable, or the energetic demand is greater than the installed power. Therefore, EE generated by RES is either directly merged into the grid or used to produce H28,18,38.

Two main configurations for a scenario in which the electrolysers and renewable systems are not connected to the electric grid can be considered. In the first one, wind power and PV systems are connected to the electrolysers, for producing H2. In this off-grid configuration, there are considerable fluctuations in the electrolyser operating conditions, given the fact that they are governed by the wind power and PV resources variability. The second stand-alone system is based on the use of electrolysers, along with H2 and FC storage. This configuration is primarily directed at the energy supply to remote areas, with no connection to an electric grid. For this reason, two energy storage stages are generally considered: one for short-term storage based on batteries, super capacitors or flywheels; and the other for long-term storage based on H2. Generally, this configuration comprises a combination of wind power and PV generators, since that their complementary nature enables to considerably increase the EE generation capacity factor 85.

A potential solution for the replacement of FF-based ES with a sustainable solar RES is a floating PV system and integrated H2 production unit. PV EE supplies the required load, and the excess energy is used in the electrolyser, for producing H2. Lands preservation by replacing their usage on PV farms, water saving due to decreased evaporation, and compensation against solar energy intermittent availability, are among the obtained results. Stored H2 is used to supply part of the electric load through FC EE. Floating PV systems decrease water resources evaporation, due to shading areas. Floating PV power plants also contribute to a better water quality, due to the reduced photosynthesis and algae growth, by blocking sunlight. Another advantage of a floating system is dust reduction. Typically, areas with high solar energy potential are mostly dusty and arid, so, floating PV systems, operate in a lower dust environment than that of their ground mounted counterparts 84.

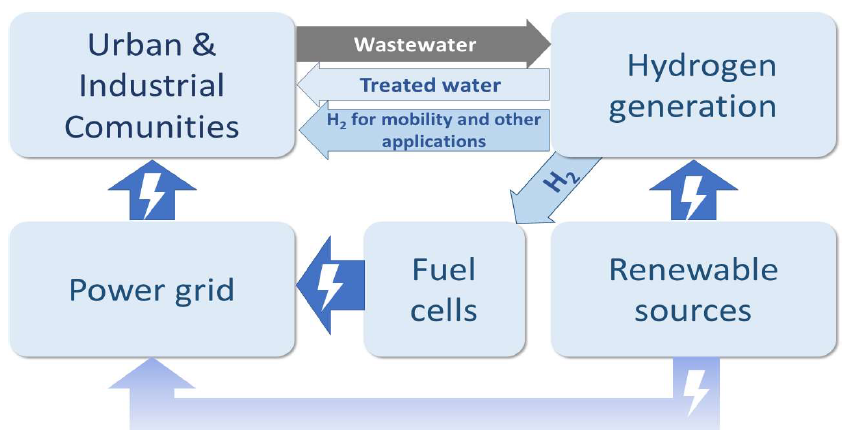

Integrating WW treatment and H2 production powered by RES can be a way to improve green H2 economy. This approach is shown in Fig. 1.

There have been a few attempts to follow this integration path. At a lab scale, textile WW direct treatment through electrolysis powered by a PV system was evaluated. The results were promising for that kind of WW 86. Similar experiments were carried out by evaluating the potential to produce H2 through ornamental-stone industries WWEL. An electrolyser prototype powered by a PV system was developed, which has shown to be effective in simultaneously producing H2 and treating WW 87. In another small-scale setup, experiments to produce H2 through electrolysis powered by PV cells, and using low-strength industrial WW, were carried out 88,89. The Greenlysis project aimed to demonstrate the potential of producing H2 via WWEL powered by renewable EE. In this approach, a PEM electrolyser and the treatment units of a WW treatment plant are powered by PV panels and wind turbines 90.

The first steps of the proposed integration approach have already been published by the authors 91.

Conclusions

This paper presents the most relevant aspects of green H2 production, essentially using electrolysers powered by electricity from RES (mainly from sunlight and wind), integrated into WW treatment processes.

The integrated approach of H2 production through WWEL powered by EE from RES seems to have the potential to boost H2 economy. The coupling of H2 production with WW treatment can contribute to simultaneously reducing the costs from the latter and the environmental impact from the former. Powering WWEL with electrical RES can contribute for balancing the electricity grid and non-RES use, towards a full greener H2 production.

Finally, nowadays, within the new paradigm of mankind activities, based on sustainability, using the circular economy philosophy, the integration of WW treatment and H2 production, powered by RES systems, becomes increasingly mandatory. Therefore, different electrolysis systems, which simultaneously treat WW and produce H2, can be a way to improve green H2.

The authors are committed to the pursuit of this idea, in the near future, through the PV system infrastructure already in place at the Polytechnic Institute of Tomar campus, with the aim to study and test the viability of H2 production from WW, by electrolysis power based on PV systems, and using H2 as fuel for different applications.

Authors’ contributions

M. Cartaxo: responsible for the paper structure; gathered information about all the work topics; inserted analyses data; promoted the discussion of the gathered data; responsible for the paper composition. J. Fernandes: helped in the analysis conception and design; provided data on renewable energies; helped in the revision and correction of the article, mainly English grammar. M. Gomes: helped in the analysis conception and design; provided data on renewable energies; helped in the analysis performance; helped in the revision and correction of the article. H. Pinho: helped in the analysis conception and design; provided data on wastewater treatment; helped in the analysis performance; helped in the revision and correction of the article. V. Nunes: helped in the analysis conception and design; provided data on wastewater treatment; helped in the analysis performance; helped in the revision and correction of the article. P. Coelho: helped in the analysis conception and design; provided data on renewable energies; helped in the analysis performance; helped in the revision and correction of the article.

Abbreviations

AWEL: alkaline water electrolysers/electrolysis/electrolytes

APWEL: alkaline polymer water electrolysis

AEM: anion exchange membrane

C: carbon

CNT: C nanotubes

COD: chemical oxygen demand

DER: distributed energy resources

EC: electrolysis cell

ECO: electrochemical oxidation

EE: electrical energy

EECS: electrochemical energy conversion and storage

ES: energy sources

ET: energy transition

ETCG: electrocoagulation

FC: fuel cells

FF: fossil fuels

GHG: greenhouse gas

H2: hydrogen

HC: hydrocarbon

HER: H2 evolution reaction

j: current density

MEC: microbial electrolysis cells

MHP: mini hydro-plant

O2: oxygen

OER: O2 evolution reaction

OM: olive mill

ORR: O2 reduction reaction

PEM: proton exchange membrane

PV: photovoltaic

RB5: reactive black 5

RB19: reactive blue 19

RES: renewable energy sources

SOEL: solid-oxide electrolysers

WEL: water electrolysis/electrolysers

WS: water splitting

WW: wastewater

WWEL: wastewater electrolysis