Introduction

Dual vocational education and training (Dual VET) has become an internationally prominent topic and, especially in Europe, within the framework of the European Education and Training policies (‘ET 2010’ and ‘ET 20202’) (OECD, 2010). In the European Union (EU), several projects, i.e., expansion of vocational pathways in the education systems, skills agenda, among others, were launched by the European Commission in 2010 based on the Copenhagen Process3 that started in 2002 and the Bruges Communiqué (EC, 2010). Governance in vocational education and training (VET) systems, of which Dual VET is a part, has become a key strategic policy area for effective modernization of VET systems (ETF, 2019) and includes the areas of financing, governance, partnerships, and quality assurance.

The focus on the implementation of VET modernization in the EU Member States has been encouraged by several European initiatives such as the Memorandum on Cooperation in Vocational Education and Training in Europe4, European Alliance for Apprenticeships5 and the News Skills Agenda6, along with more recent policies for education and training in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (EC/COM, 2020a; EC/COM, 2020b). The recommendation to the Members States is to give stronger support to youth employment measures, education, and skills, through the reinforcement of Dual VET programmes and the involvement of social partners in the structures of governance (EC/COM, 2020a).

The main objective of vocational education and training (hereinafter VET) is to provide the education and training programmes to equip young people and adults with knowledge, know-how, skills and/or competences required in certain occupations or, more broadly, on the labour market and may be provided in formal and in non-formal settings, at all levels of the European Qualifications Framework, including at tertiary level (EU/COM, 2020). Dual vocational education and training (hereinafter Dual VET), as defined by Cedefop (2016), combines workplace learning in an enterprise with classroom teaching in an educational institution. In other words, Dual VET requires ‘the dualism of theoretical instruction and practical learning in the work process’ (Cedefop, 2016).

Both VET and Dual VET programmes must have a work-based training component, which is more pronounced in the Dual VET programmes, whereas the former ones have a larger percentage of school-based education and training. The consensual definition of school-based VET is the one that involves the combination learning were at least 75% of the theoretical learning takes place at school (school-based VET) and 25% in a company (Cedefop, 2012). As for work-based learning in Dual VET, a large proportion (generally from 50% or more) of learning takes place in companies and is complemented by school-based learning (Šćepanović & Martín Artiles, 2020). In a wider sense, Dual VET can be also considered an ‘Apprenticeship’ (Cedefop, 2016). Although, in practice, VET also exists and combines long phases of full-time school based vocational education with usually shorter periods of on-the-job learning (Rauner & Wittig, 2010). The governance of Dual VET is often seen as important for the education and training systems. According to several authors, the effective collaboration between the government (central, regional and local), employers, trade unions, industry representatives, training companies/providers, vocational schools is considered to have positive societal and economic effects (Bonoli & Wilson, 2019; Cedefop, 2016; Emmenegger & Seitzl, 2020). Furthermore, the involvement of social partners and other industrial (private) actors contributes to the development of VET public policies enabling the operationalization of the policy functions at regional and local level (ETF, 2019). As referenced by Azevedo (2009, 2014), this involvement is a key factor for the success and accomplishments of the qualifications and work opportunities of VET programmes.

However, the involvement of actors or stakeholders in VET and Dual VET governance is often complicated and challenging (Gordon, 2015; Oliver, 2010). There are important cross-national differences: i) the social partners do not always participate in the decision making at the political-strategic level; ii) their involvement is not always on equal terms (parity), with trade unions in some cases being less strongly involved; and iii) differences in VET governance are particularly pronounced at the technical-operational level (Emmenegger & Seitzl, 2020).

VET and Dual VET systems also differ in their organisations among countries (Euler, 2013). Whereas in some countries, e.g., Germany, Dual VET is a long-established system that also serves as a typified model for other countries, in other European Member states (e.g., Bulgaria, Hungary, Italy, Slovakia, Spain, Romania, Poland, and Sweden) Dual VET programmes have intensified between 2010 and 2018 as part of reforms targeting to reduce youth unemployment and improve Europe’s industrial competitiveness and social cohesion (Euler, 2013; Šćepanović & Martín Artiles, 2020).

Furthermore, different roles are played by the state and other social partners in the determination and implementation of VET policies (Green, 1997; Nielsen, 2011). There are countries in which employers’ inputs are collected through representative bodies, e.g. Germany, Austria and Denmark, where employer representatives, sector councils and chambers that may nominate individual companies to take part in the design process. In Portugal, alongside with Poland, Slovenia, and Scotland (UK), the representing employers and employees monitor labour market needs, within their specific activities, in sectoral councils to adjust the learning and occupational-related outcomes of VET qualifications according to the specific business needs (Cedefop, 2020). The design process in Portugal, however, is more centralized in the government (Cedefop, 2016; OECD, 2020).

The involvement of social partners in the governance structure of VET in Portugal, namely, employers’ confederations and trade unions, was legally established throughout 1980s - 1990s, within The Professional Training Policy Agreement signed in 1991 by the members of the Permanent Commission for Social Dialogue (CPCS)7 (Torres & Araújo, 2010). However, effective participation of social partners in the governance of the Dual VET system in Portugal requires special attention. As argued by Sanz de Miguel (2017), the role played by social partners in the Iberian VET systems (Spain and Portugal) is less institutionalized and their integration in the Dual VET governance is low and relies significantly on the state regulation compared to other European countries. More specifically, Portugal has been referred as one example of lower levels of institutionalization and integration.

The aim of this paper is, therefore, to understand the role of social partners in the governance of the Portuguese Apprenticeship system with a focus on their formal roles and how governance is organised. The social partners in this article are presented in a wider scope such as the employers’ confederations and federations, trade unions, and sectoral associations. The article is organised in the following way. First, we present the description of the research method and a contextual framework of the Portuguese Dual VET programmes addressing the recent developments in the Dual VET. Second, based on the literature review and different sources of information, the paper presents the description of the formal role of social partners in the governance structure of the Apprenticeship system. The article closes with conclusions drawn from the overall literature findings.

Research method

This paper is part of the European research project INVOLVE8 that analyses the social partners’ integration and participation in the governance of dual VET systems in four European countries (Spain, Greece, Poland, and Portugal). The present article refers to the initial phase of the desk research aiming to develop an extensive review of the literature on the subject of Dual VET and its governance in Portugal. In this phase, we do not aim to compare governance system in Portugal with the remaining countries.

The paper is presented as narrative review or ‘overview’ as the “traditional” way of reviewing the extant literature and is skewed towards a qualitative interpretation of prior knowledge (e.g., Paré & Kitsiou, 2016, p. 161). Its primary purpose is to provide the reader with a comprehensive background for understanding current knowledge on the topic (Cronin, Ryan & Coughlan, 2008). In other words, a narrative review or ‘overview’ attempts to summarize what has been written on a particular topic but does not seek generalization or cumulative knowledge from what is reviewed (it is rather unsystematic narrative review) (e.g., Green, B., Johnson & Adams, 2006). Narrative overviews, according to Green, B. and colleagues (2006, p. 103), “pull many pieces of information together into a readable format, are helpful in presenting a broad perspective on a topic and often describe the history or development of a problem or its management”.

The information presented in this paper is based on extensive online searches of academic literature published after the year 2000, a period characterised by the expansion of VET systems and policies across Europe. Furthermore, the period of data analysis as specified in the terms of reference of the INVOLVE project, refers to the school period starting from 2010 onwards. The authors consulted national and international scientific online databases, namely ‘Nova Discovery’, which aggregates the main databases of scientific articles, B-On (the main scientific engine in Portugal), institutional repositories of Universidade Nova de Lisboa, and Science Direct. Additionally, statistical information is derived from official data on VET collected by national and international organisations such as the Directorate General on Statistics and Science (DGEEC), Directorate General for Education (DGE), Statistics Portugal (INE), Institute for Employment and Vocational Training (IEFP), National Agency for Qualifications and Vocational Education and Training (ANQEP), Competitiveness Agency and Innovation (IAPMEI) and the Institute of Tourism. Searches were also conducted in Google Search engine to assure the widest cover possible of publications related to the topic. The national policy debate on VET (and Dual VET) was reviewed using several sources, mainly B-On, Science Direct, web searches, Recaap, Google Scholar, mainly the discussions published in online magazine Futurália, major Portuguese newspapers (Expresso, Público and Observador), as well information presented on the websites of employers’ associations and trade unions.

To clarify the national debate on Dual VET, a broad spectrum of the literature was consulted, both scientific and ‘grey’ literature, the statistical information on VET and Apprenticeship in the Portuguese education system, and related government and legislative documents.

Contextual framework of the Portuguese Dual VET programmes

Since 1984, Dual VET was enshrined and strongly consolidated in the legal system of Apprenticeship (Sistema de Aprendizagem or simply Aprendizagem9). The Apprenticeship system was managed through the National and Regional Apprenticeship Commissions, of tripartite composition involving the Ministries of Labour, Education, Internal Affairs and Economy, as well as two representatives of trade unions and two representatives of employers’ confederations. Presently, the Apprenticeship system is regulated and supervised by the Ministry of Labour and is provided in a work context through the Institute of Employment and Vocational Training (IEFP) which has the social partners with a seat in the tripartite Standing Committee for Social Dialogue (CPCS), represented in its board of directors.

After Portugal signed the Berlin Memorandum in 2012, a new German-inspired10 pilot project of Dual VET courses was introduced in the Portuguese education system, regulated and supervised by the Ministry of Education. It was in line with the recommended guidelines from international organisations such as OECD, UNESCO and, particularly, the European Commission (CNE, 2014a). This pilot project for lower secondary education started in the school year of 2012/2013 as an experiment, and for upper secondary education in the school year of 2013/2014. After the creation of this pilot project of Dual VET in 2012 and 2013, 30% of VET programmes for youngsters in Portugal were Dual VET (DGEEC, 2020). However, in 2016 the pilot project was terminated. In 2017, students were still attending the pilot project of Dual VET courses only to complete it. Both the introduction of this pilot project and its subsequent closure in 2016 raised extensive political debate.

The policy debate on Dual VET involved the main social partners (employers and employers’ confederations) and other stakeholders (directly and indirectly related to the training system), through the intervention of the Association of private VET schools (ANESPO) represented in the National Council of Education (CNE). Initially, the debate centred around the draft legislative proposal for the creation of Dual VET courses for lower and upper secondary students in the education system. It raised concerns about the compliance of the Dual VET pilot project with 12 years of compulsory education, as well as the age of the students for whom it was intended (CNE, 2014b).

The relevance of the pilot project of Dual VET to the existing VET system was also questioned by the representatives of the education sector in Portugal. For instance, the Council of Schools (Conselho das Escolas) - an advisory entity to the Ministry of Education representing the network of public education establishments - issued a Technical opinion document (Parecer 3/201711) referring to the lack of correspondence of the courses of the pilot project to a qualification level according to the European System of Qualifications and the National Qualification Framework. Furthermore, the mainstream media (e.g., numerous publications retrieved from Expresso journal12) questioned if the pilot project objectives were designed to improve the students’ school success or just to “clean up” statistics of underachievement rates in regular education. The online newspaper Observador (201713) also questioned if the termination of vocational courses under the pilot project was purely “an ideological choice based on an intellectual prejudice”. The newspaper Público (201714) referred to the discontinuation of the pilot project of Dual VET as a measure dictated by the government amendments for basic and secondary education organisation of the curricula, in order to tackle early diversion of students to vocational paths, particularly at lower secondary level of education.

Regarding academic debate, some studies have analysed school-based programmes and discussed the results of the pilot project of Dual VET and its failure (e.g. Dias, Hormigo, Marques, Pereira, Correia & Pereira, 2017; Pereira, 2012; Pinto, Silva, Delgado & Diogo, 2020). These studies framed the analysis in a comparative context with the German model indicating the constraints encountered by public schools in Portugal in combining school-based training with 50% of work-based training and presented different perceptions of students and teachers about the project. As such, students considered the pilot project important for their immediate entry into the labour market due to the skills acquired, whereas the teachers reported the project insufficient to achieve objectives of school success. Literature inspired in German-speaking model demonstrates that social partners are considered important to balance and promote Dual VET systems (Pinto, Silva, Delgado & Diogo, 2020). Besides scientific literature, the evaluation and monitoring technical reports of the pilot project of Dual VET have been published by governmental entities (DGEEC, 2015; DGE/MEC, 2015). These reports demonstrated that there was strong take up of students and a good completion rate, as well as good adherence of companies to the pilot project.

The publications encountered about Dual VET (the Apprenticeship system) refer to the relevance of on-the-job or work-based training to the social integration of students in the labour market (Alhandra, 2010), and the possible effects of Apprenticeship courses on the promotion of social justice and its stigma (Doroftei, 2020). Another study about the Apprenticeship system (Torres & Araújo, 2010) has identified the legislative measures that contributed to clarify the institutional framework of initial and continuous VET. The system until 1991 lacked clarification on the roles to be played by each educational and training actor. In this latter analysis, the authors study this institutional framework and the nature of each existing VET programme reaching the conclusion that Apprenticeship courses constitute a real alternative to initial dual certified training for young people and not only “more of the same” (Torres & Araújo, 2010). Importantly, we could not find sufficient research about the governance of Dual VET in Portugal. In particular, none of these publications discusses the role of social partners and other stakeholders in the Portuguese Apprenticeship system and the pilot project of Dual VET.

We detected pressures from the teachers’ unions, which are important actors in the education system and educational advisors of the National Council of Education (FENPROF, 2013). They presented two arguments against these Dual VET courses: (1) these courses did not lead to a qualification level; and (2) the reduction of the cultural and scientific /technical teaching in the curricula matrix was not acceptable in the context of the cultural role of education. Furthermore, some actors, mainly teachers from the public and private network of VET schools reported the need of integrating the students attending pilot project of Dual VET into compulsory education, drawing attention to the possible transfer of these students to training centres. In fact, these actors claimed that the pilot project of Dual VET lasted less than three years, which is less than the time of completion of the compulsory education. Others such as the representatives of the Association of the network of private VET schools (ANESPO) and the teacher’s unions were concerned about the early diversion to vocational paths from students aged 13 (CNE, 2014a).

There is one European report (Cedefop, 2016) that indicates low involvement and integration of the various bodies with the Portuguese institutional framework. Taking this scarcity of the literature on the topic, this paper will contribute with results about the structure of the governance of the Apprenticeship system in Portugal, as the Dual VET pilot project in the country, its developments and identify the role of social actors and other stakeholders in this system.

VET and the Apprenticeship system

The established VET system includes courses provided at the lower secondary level, upper secondary level, post-secondary non-higher and higher level of education, for pupils of 13 years of age and above, and last from one to three years. Upper secondary VET consists of school-based vocational courses (Level III and IV of the National Qualifications Framework - NQF), technological courses and education and training courses (CEF) and non-tertiary post-secondary courses where school-based training predominates, and an ‘second chance’ programme (hereafter, Apprenticeship or Aprendizagem) with alternating periods of education and training at training centres and at the workplace. The courses under the Apprenticeship system are equivalent to ISCED 3 and to Level IV of the NQF. The Apprenticeship system is designed mainly for upper secondary students aged 20 to 24 with at least nine years of secondary education or above, but not having completed 12 years of secondary education, although students from age of 15 can also attend the programme.

The extent of practical training component varies depending on the type of the education and training area. On one hand, VET programmes are mostly school based, where students spend only from 19 to 27% of training time in the workplace. In this type of courses, the training providers are mainly public or private schools under the supervision of the Ministry of Education that engage with employers in establishing partnerships for workplace training and ensuring the technical components of the curriculum as well as the evaluation of the internships.

On the other hand, Apprenticeship students spend at least 40% of their time in the workplace training that is provided mainly by the IEFP direct management and participated management training centres (centros de formação de gestão direta e de gestão participada do IEFP). These training centres function under a protocol with the IEFP that combines participation of employers’ associations, companies, trade unions or private for-profit centres autonomously managed. In addition, other types of organisations may participate in the Apprenticeship programmes, such as external training organisations (public or private) that deliver the school-based education and training components and monitor the training in the work context. All these providers are under the supervision of the IEFP.

On what concerns social support, the training provider signs a contract with students that indicates the amount (allowance) available to the apprentice (trainee) if eligible under the School Social Action (ASE - Ação Social Escolar), which includes a personal accident insurance under the responsibility of the training provider. The training provider is responsible for organising the training and ensuring the workplace safety, as well as providing transportation for trainees to/from the place of training. In addition, students receive a daily allowance for transport and meals in total monthly amount up to €257, depending on the conditions of the contract and the eligibility within the ASE.

Presently, the Apprenticeship system is funded through the IEFP by the national Operational Program of Human Capital (POCH - Priority axis 3) and the Single Social Tax15 paid by workers and employers. The financing from the community funds, particularly the European Social Fund, depends on the submission of projects by the IEFP. Nonetheless, a private training academy ATEC (a centre promoted by Volkswagen AutoEuropa, Siemens, Bosch Thermotechnology) and the German-Portuguese Chamber of Commerce and Industry, offers Dual VET courses within a contract established with IEFP.

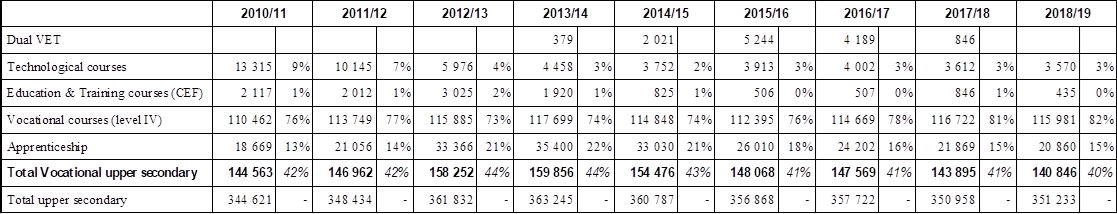

Overall, the number of students in Apprenticeship programmes has been increasing, despite a decrease in the students attending upper secondary VET (see Table 1).

Table 1 Note: Source: Number and distribution of students attending upper secondary VET in Portugal, from 2010/11 to 2018/19 Data refers to young students in compulsory education in Portugal, the period of reference refers to 2010 onwards according to the terms of reference of the INVOLVE project. DGEEC, Statistics of Education 2010-2019; Education in Numbers, 2020

Table 1 also indicates that in school year 2018/19 the upper VET system represented 40% of all upper secondary students. This showed a small decrease compared to 2010/11, where the upper VET system represented 42% . The stability found during this period indicates that the main choice of the students attending was the general education (60% in the most recent year). Furthermore, school-based VET included vocational (82%) and technological courses (3%) in 2018/19. Thus, most upper secondary VET students attended school-based courses.

In addition, the Apprenticeship system represented 15% in 2018/2019. In 2010/11, there were 13% of the upper VET attendees. Thus, the Apprenticeship system has been continuously the second most popular choice among enrolments of upper VET students, following vocational courses. Interestingly, the Apprenticeship registered significant variations: the programme lost 14 907 students in the last six years; and between 2013/14 and 2018/19 the number of students decreased 41.1%. Furthermore, the following table provides an overview of the most popular areas of education and training in the Apprenticeship system.

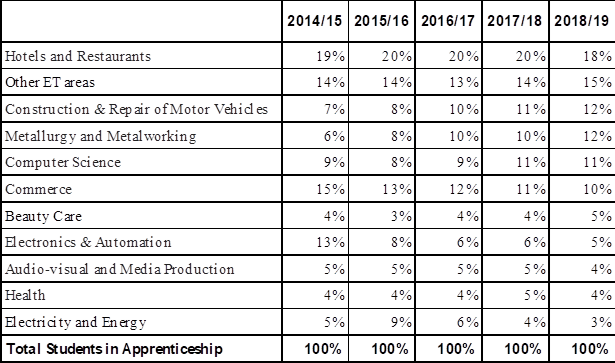

Table 2 Note: Source: Number of students in the Apprenticeship by area of education and training, from 2014/15 to 2018/19 Refers to students attending Apprenticeship in the Continent, youngsters DGEEC: Statistics of Education: Students Attending by CNAEF, 2013-2019 (2014/15 - first year with data)

As shown in Table 2, the most popular areas in the Apprenticeship in the school year 2018/19 were Hotels and Restaurants, Other ET areas, Construction & Repair of Motor Vehicles, Metallurgy and Metalworking, Computer Science and Commerce (representing 78% of the students attending), out of the eleven choices in total. In 2014/15, the areas with more attendees were less concentrated and more distributed, with the four most popular choices (representing 61% of the students) in Hotels and Restaurants, Commerce, Electronics & Automation, and other education and training areas. Computer Science, Construction & Repair of Motor Vehicles, Metallurgy and Metalworking, Electricity and Energy and Audio-visual and Media Production16 had less than 10% of students enrolled in this academic year. Furthermore, all courses lost students with the notable exception of Construction & Repair of Motor Vehicles and Metallurgy and Metalworking. In sum, the Apprenticeship choices of training areas present a concentration pattern and increase of students in Construction & Repair of Motor Vehicles and Metallurgy and Metalworking.

The governance structure of Apprenticeship

International literature on VET and industrial relations has given great importance to the question of governance (Chatzichristou, Uličná, Murphy, Curth & Nogueira, 2014; EC, 2014; Gordon, 2015; OECD, 2020). In this context, VET governance refers to: “all mechanisms, practices and procedures (e.g financing, evaluation, administrative processes, etc.) that address the interdependence of actors in complex social environments with the aim to allow for the coordination of activities to resolve common problems or the achievement of shared ends” (Mayntz, 2006, as cited in Cedefop, 2016, pp. 22, 35).

Governance of VET and Dual VET is a multi-level system that includes very diverse actors (experts, individual firms, business intermediary associations, trade unions, educational organisations and public authorities) who cooperate on the effective provision of training (Bliem, Petanovitsch & Schmid, 2014; Emmenegger & Seitzl, 2020). Cedefop (2016, p. 36) indicated four principal types of actors: governmental and administrative bodies, education and training providers, social partner organisations and the labour market, whose roles may be ‘steering’ or ‘signaling’. Social partners generally refer to trade unions and employer organisations (Nielsen, 2011).

The Portuguese Government remains the key player in promoting vocational education and training as an alternative education path. The Ministry of Labour is in charge of the Apprenticeship system through the IEFP. The IEFP is the public national entity responsible for implementing the employment and initial and continuous vocational training policies defined and approved by the Government. It is the main driving force in the development of work-based VET programs. Its responsibilities include organisation of the work context and technical components of the curriculum and training provision. The IEFP is the principal financial provider and plays the main role in everything related to vocational training (initial and continuous) and employment. It has a diversified presence in its Board of Directors and Supervisory committee. The Board of Directors includes representatives of trade unions and business confederations with a seat in the CPCS and CES, as well as public administration representatives. The Board discusses the annual IEFP activity plan that requires approval by its members. The IEFP also has Regional advisory councils, which are employment consultation bodies that work with each of the territorial areas where regional delegations operate. In addition, the network of Participated management training centres has been created under protocols signed between the IEFP, the social partners (employers' associations, trade unions and professional associations) and other stakeholders, oriented to sectors of economic activity (civil construction, metallurgy, metalworking, cork, food, fashion, commerce, etc.).

The involvement of social partners in the governance of Apprenticeship is statutory regulated. In fact, within the Professional Training Policy Agreement signed in 1991, the role of social partners both as beneficiaries and providers of VET was legally defined through the Decree-Law 405/91 of 16 October. As defined in this Law, work-based VET is to be provided by the social partners represented in the CPCS. These partners should also contribute to the definition of VET policies, by participating not only as stakeholders but also as coordinators in the governance structures of the ANQEP (General Council) and of the IEFP, where they should tackle issues of the Apprenticeship System.

ANQEP is the National Agency for Qualification and Vocational Education and Training that regulates the VET system for youngsters and adults. Regarding employers’ associations and trade unions, their main role is to participate through sectoral councils composed by specialists in the definition of vocational profiles, training references and occupational standards associated with qualifications. The specialists - whose mission is to support the development and upgrade of the National Qualifications Catalogue - are appointed by trade unions and employers’ organisations; reference companies; training entities and academies; competent authorities regulating access to professions; technological centres and independent experts, among others, such as government structures (Directorate-General for Education, School Establishments and for Employment and Labour Relations), councils of university deans, associations of private and cooperative education establishments, association of private VET schools and the management of the Human Capital Operational Programme (POCH).

The employers’ associations are involved in the Apprenticeship by participating in regular meetings of the CPCS and providing vocational training (themselves or through their associated members) and in VET by participating in the General Council of ANQEP: the Portuguese Tourism Confederation (CTP), the Confederation of agriculture (CAP), the Confederation of Commerce and services of Portugal (CCP) and The Business Confederation (Confederação Empresarial de Portugal, CIP).

The CTP is an important actor in VET promotion in the training areas of tourism and restaurants. CTP has a seat in the CPCS since 2003 and brings together all tourism business federations and associations. Training programmes are provided by several of its associates, but for them the main player is the governmental agency “Tourism of Portugal17” with its twelve VET schools that provide upper secondary and post-secondary VET. The CAP18 also provides training through its associates (about 250 federations and associations) and runs three regional training centres. Although CAP has a say in CPCS, it is more a player on VET then a driver because agriculture is not one of the most chosen areas by VET students.

Finally, the business confederation CIP represents 150 thousand companies in all sectors of the economy. Most of its associates are important players in VET, acting locally and in the sectors in cooperation with different technological centres. Importantly, three CIP associates are important players in VET and political influencers: The Association of Metallurgical, Metalworking and Related Industries (AIMMAP), Portuguese Association of Electrical and Electronics Companies (ANIMEE) and the Chamber of Commerce and Industry. These Associations participate in Sectoral Councils for Qualification (CSQ) of ANQEP supporting the definition of education policies in their areas.

The social partners (trade unions and employers’ confederations) are also involved in the coordination of National System of Qualifications (SNQ) through it in the General Council of the ANQEP, and in the monitoring committee of the quality certification of training entities.

Another actor to be recognised as an important Dual VET driver is the ATEC Academy that has a cooperation agreement with the IEFP to provide Apprenticeship courses and promotes Dual VET, together with the German-Portuguese Chamber of Commerce and Industry, organising workshops, conferences and training initiatives with the involvement of schools, municipalities, companies and other stakeholders.

Regarding the VET system, the association of private VET schools ANESPO19, which was created in 1991, has been an important if not the main VET driver in the country. This association brings together more than 200 private VET schools that belong to the different private entities, including business associations, foundations, cooperatives, municipalities and trade unions, and provides support to its associates and organises training for VET teachers and trainers. ANESPO has also established protocols with more than 20 companies to guarantee its associates the internships, work-context training and even training equipment20. A recent debate leaded by ANESPO was about the government's decision to provide textbooks to students in general and vocational education in the network of public schools but excluding students from VET in the private network. The trade union FENPROF disagreed with this measure announcing discrimination against these students (especially from disadvantaged families who are more present in vocational education), because initially free textbooks were extended to all compulsory education, including vocational education, and covered private schools (Observador, 201921).

Formally, ANQEP supports, coordinates, regulates and supervises VET and Dual VET (at lower and upper secondary education level) and the qualification policies for adults in both private and public VET schools. It is not clear the actual role it plays in Apprenticeship.

The role of social partners found in main institutional arrangements of Apprenticeship can be summarized in the following table:

Table 3 The roles of social partners in the governance of Apprenticeship

| Involvement. Yes/no | Type of involvement | |

| Development and renovation of curricula for Dual VET | No | The development and renovation of curricula for Dual VET is under responsibility of the Ministry of Education |

| Evaluation of the System | No | The evaluation is under responsibility of the General Inspection of the Ministry of Labour and Ministry of Education for the case of the Apprenticeship courses and Vocational Training |

| Monitoring of the system | Yes | Social partners participate in the Board of Directors of the IEFP that provides, regulates and supervises the Apprenticeship System and are represented in the ANQEP, which is mandated to monitor VET policies and the National Framework of Qualifications. |

| Delivering of education | Not directly | Not directly |

| Evaluation of students’ training outcomes | No | |

| Regulation of working conditions of “apprenticeships” or “internships” | Yes | Social partners have a formal role to participate by calling attention in the CPCS and Board of Directors of working conditions of “apprenticeships” or “internships” that need to be taken into account. |

| Enforcement of working and training conditions of “apprenticeships” or “internships” | Yes | Social partners have a formal role to participate by calling attention in the CPCS and Board of Directors in the enforcement of working and training conditions. |

Source: Compiled by the authors

The table reveals that social partners with seats at the CPCS have a formal representation in the governance of Apprenticeship. They monitor of the system through their seats in the Board of Directors of the IEFP, which provides, regulates and supervises the Apprenticeship System, as well as in ANQEP, which is mandated to monitor VET policies and the National Framework of Qualifications. Social partners also have a formal role in the regulation of working conditions of apprenticeship system through CPCS and Board of Directors. In addition, social partners have a formal role to participate by calling attention in the CPCS and Board of Directors in the enforcement of working and training conditions.

Social partners in the Apprenticeship system

The involvement of social partners in the Apprenticeship system varies significantly according to several factors. First, social partners participate in the discussions on financing that normally take place separately due to the nature of the funding sources of each VET programme. As such, the financing of the Apprenticeship system is discussed through negotiations that take place within the Board of Directors of the IEFP at the regional level and in the CPCS. The VET in public schools is financed through the State budget and the negotiations take place in meetings with the Ministry of Education, where the teacher’s trade unions participate. And the private network of VET schools is financed mainly through European funds (except for the regions of Lisbon and Tagus Valley and Algarve which are financed from the State budget), and the negotiations involve mainly the Ministry of Education and the National Association of the network of private VET schools - ANESPO.

The financing of VET and Dual VET courses is a complex process that usually involves many stakeholders. For example, the involvement of the teacher’s union in 2017 contributed indirectly to a further increase in funds of VET. The teachers’ union (FENPROF, 2017) paid attention to the scarcity of funding for VET22, referring that the situation was such that could rapidly undermine the government guidelines for VET in public schools. In 2018, the government announced an allocation of 240 million euros for VET in public schools to be entered in the 2019 state budget (Público, 201823). Even there might be no direct relation between this increase in funds and the FENPROF statement, the alternating VET clearly benefited from this measure directed to strengthen the material and human resources for VET in public schools.

The most active social partners involved in the Apprenticeship are the employers. Trade unions and employers’ confederations and their affiliates are more concerned with work-based VET - Apprenticeship - than with VET due to the contribution of work-based training to qualified employment. In contrast, VET has more intervention from teachers’ unions (mentioned above) and other stakeholders’ federations and school’s councils. This is their referential matrix. For instance, the Council of Schools in its Technical Opinion document (ref. 3/2017) recognized the importance of diversified training offers to prevent dropout and early school leaving, although supported the termination of the pilot project of Dual VET programmes. The Council of Schools argued in 201724 that this Dual VET programme did not have adequate qualification to match the European system of qualifications. In addition, these courses were not organised and structured in a way to provide students a consistent vocational and training path, but rather served as a second option for students with learning difficulties.

Conclusion

This article has investigated the role of social partners in the governance of Dual VET in Portugal. We found that the scientific literature about the Apprenticeship system is particularly scarce. Nevertheless, there were international literature referring to the involvement of social partners in VET and Dual VET systems. Among them, Cedefop (2016) and OECD (2020) have presented the information about the structure of governance and financing of the VET system in Portugal. Other authors focus their analyses in the VET and Dual VET programmes, comparing the system in different countries, and the strategic levels of social partners and stakeholders involvement in governance (Emmenegger and Seitzl, 2020; Rauner & Wittig, 2010; Šćepanović and Martín Artiles, 2020). Some describe the changes in the traditional pedagogical concept of apprenticeship based in the master-apprentice relationship to the principle of ‘duality’, understood as combination of classroom teaching and in-company training (Markowitsch & Wittig, 2020).

Whereas the role of social partners is situated in the international literature, there is no assessment of their effective contributions to the involvement in the governance of Dual VET. Furthermore, in the Portuguese literature some authors have analysed Dual VET from different angles (e.g., Alhandra, 2010; Doroftei, 2020; Torres & Araújo, 2010). Nevertheless, the lack of literature specifically related to the governance of Dual VET reflects the absence of national research on the effective role of social partners. In the future, our fieldwork will provide more detailed knowledge on the effective participation of social partners for the development of Dual VET.

In the frame of our research, we discussed that presently there is only one program close to Dual VET concept in Portugal: the Apprenticeship system. This programme is consolidated in the country since 1984, has been steady in terms of students’ attendance since 2010 and represented 15% of VET students in 2018/19. There are also small Dual VET courses provided by the private training Academy ATEC.

A pilot project of Dual VET started in 2012 but finished four years later. We identified a rejection of the programme by major stakeholders. Trade unions, for example, remained sceptical or even critical of Dual VET programmes. We agree with Sanz de Miguel (2017) in that some reforms of Dual VET in Europe have been approved in a context of deterioration of social dialogue and industrial democracy. The period related to the Troika presence in Portugal was one of those contexts, which favoured its failure. Nevertheless, we think this requires further research that is beyond the scope of this paper.

Overall, the involvement of social partners and stakeholders has always been a reference in the European strategies and guidelines for the Education and Training systems to guarantee the effectiveness of VET systems. Likewise, the participation of social partners in the development of Portuguese VET was considered crucial. Since 1986, it has involved different frameworks of social partners on a contractual base with the Ministry of Labour and/or Education (Azevedo, 2009, 2014).

They participate in a formal way in monitoring the system, as well as regulating and enforcing Apprenticeship. However, whether their role in the governance has been effective is difficult to conclude. Organisationally, their voices are heard mainly indirectly in the governance structures of VET and the Apprenticeship. More specifically, the IEFP provides funding for Apprenticeship, and social partners negotiate in its Board of Directors the allocation of the Single Social Tax for the regional centres, as well as the creation and governance of Apprenticeship courses and, to a certain extent, the number of students. The social partners’ concerns tend to be more related with employment policies promoting qualifications of workers and qualified employment. Despite descriptions of their formal roles, we found no evidence of their effectiveness. In addition, there is not a large discussion in the civil society about Dual VET in the country, apart from the period in which the pilot project of Dual VET was introduced. The next stage of the Project INVOLVE includes fieldwork research with interviews with the main social partners, stakeholders, and companies, to draw light on their effective role in the Portuguese Dual VET.