Introduction

The increase in life expectancy and the decline and postponement of childbearing have led to a reduction in the number of members of a family horizontally; however, vertically, there is the possibility of more generations living per family. The study of parenthood and of grandfatherhood is important, even more so because the 21st century in Europe is the “century of the elderly and the grandparents” (Ramos, 2014, p. 35).

The birth of a grandchild is not a transition that depends on the grandparents’ willingness or planning and it occurs at the same time as their children’s transition to parenthood. Each individual experiences their life cycle as part of the family life cycle. A change experienced by a family member inevitably affects the other members. The transition to grandfatherhood is an event that is inevitably out of the grandparents’ control. In life and human evolution, changing is inevitable, although these changes do not have to be natural or desirable. Grandfatherhood is an area sensitive to nursing care.

Based on the following broad research questions: “How is the process of transition to grandfatherhood?” and “What are the characteristics of the performance of the grandfather’s role in family health?”, this study aimed to: Describe the process of transition to grandfatherhood and characterize the performance of the grandfather’s role in family health. Nursing as a discipline uses Grounded Theory as an interesting instrument for reflection and action with a view to organizing the knowledge process. The research method that guides this study is the Grounded Theory, based on Strauss and Corbin’s approach (2008).

1 Theoretical framework

The concept of grandfatherhood is comprehensive (Coimbra de Matos, 2006) and associated with the universe between grandparents and grandchildren. It begins during pregnancy, a transition period in the life cycle of the family, with transformations at all levels, including in family relationships. For future grandparents, the birth of a child means that they are getting older and climbing one step in the generation hierarchy. Exploring the transition to grandfatherhood is acknowledging a process of transition to a new phase of life and taking on a new role that may be symbolically associated with old age and death.

Becoming a grandfather is an increasingly frequent phenomenon worldwide as a result of an increase in average life expectancy. The birth of a grandchild is a milestone in the family life cycle and changes both the family structure and the grandparents’ psychological structure, giving them a new identity and new roles (Kipper & Lopes, 2006). Becoming a grandmother/grandfather for the first time is one of the major transitions in the life cycle (Taubman - Ben-Ari, Findler, & Shlomo, 2013). A better understanding of the variables associated with this process can help health professionals to plan the interventions necessary to help grandparents to experience this life phase in a positive way (Shlomo, Taubman - Ben-Ari, Findler, Sivan, & Dolizki, 2010; Taubman - Ben-Ari, Findler, & Shlomo, 2013). The transition to grandfatherhood is characterized as a happy occasion, with major transitions in the individual and the family environment, but it should also be seen as an event causing stress and change (Taubman - Ben-Ari, Findler, & Shlomo, 2012).

Developmental transitions, such as the transition to grandfatherhood, influence the individuals’ health and well-being and may or may not require the involvement of health professionals and the health system. Developmental stages and roles influence health-disease behaviors, and only by studying them can we understand how individuals respond to these transitions (Meleis, 2015).

Exploring the transition to grandfatherhood is acknowledging a process of transition to a new phase of life and that men assume a new role in family health.

The contextualization of the grandfather’s role in family health contributes to describing the process of grandfatherhood and helping nurses to outline interventions for facilitating the transition to grandfatherhood and helping grandfathers to understand their roles within the family (Coelho, Mendes, & Rodrigues, 2019).

Methods

2.1 Study type

As a research methodology of Grounded Theory, Strauss and Corbin’s approach (2008) was used in the techniques and procedures to meet the following objectives: To describe the process of transition to grandfatherhood and characterize the performance of the grandfather’s role in family health.

Qualitative research is considered to be the most appropriate way of gaining access to meanings (Ferreira, 2013); it emphasizes the processes that do not accurately measure quantity, intensity, or frequency, aims to understand the essence of human experience, seeks holism, whose objective is to find dimensions, and generates theories (Carpenter, 2013). Grounded theory is a qualitative research approach, known in Portuguese as Teoria Fundamentada nos Dados or Teoria Fundamentada (Dantas, Leite, Lima, & Sipp, 2009; Carpenter, 2013; Strauss & Corbin, 2008). Strauss and Corbin (2008, p. 25) define Grounded Theory as “…theory that was derived from data, systematically gathered and analyzed through the research process.” Grounded Theory emphasizes the importance assigned by the research subjects to the research target (Laperrière, 2010).

2.2 Sample

As it is not possible to begin a research study with a well-defined research question, the sample using the Grounded Theory method is impossible to predict a priori. Data collection and analysis will establish the number of subjects in the sample. Theoretical sampling is used to maximize the opportunities to compare facts, incidents, or events to determine how a category varies in terms of properties and dimensions. In general, as the researcher builds his or her diagram with the representation of ideas, he or she is also contributing to the theoretical sampling. Sampling is guided by logic and the objective of the three types of coding (Strauss & Corbin, 2008). Theoretical sampling aims at theory construction, rather than at the representativeness of the population. Theoretical sampling is flexible, depends on the analysis of collected data, and determines the subsequent collection. As data analysis continues, the researcher can deliberately include those that are susceptible to generate more relevant data to the emerging concepts (Green & Thorogood, 2004).

The intentional sample of the study, which was composed of 26 grandfathers, aimed to answer the research questions set out.

2.3 Data collection tools

The 26 semi-structured interviews took place between October 2016 and May 2018, usually in places chosen by the grandfathers. Each interview lasted, on average, 50 minutes. All interviews were recorded and transcribed, as well as the field notes, and then coded using Excel®, version 2013.

2.4 Inclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used in this study: legally recognized biological or adoptive grandfathers of, at least, a grandchild aged 10 years or less; soon-to-be grandfathers; having, at least, the first official level of education. The following exclusion criteria were applied: grandfathers with disabling physical illness and grandfathers with severe mental illness whose interview was not possible. The criteria were investigated when the interview was scheduled and verified on the day of the interview.

2.5 Procedures

In compliance with the ethical research principles advocated by the scientific community, the research project was submitted to the Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing of the Nursing School of Coimbra, which issued a favorable opinion.

Other ethical assumptions advocated by the scientific community consist of obtaining informed consent and maintaining confidentiality (Carpenter, 2013). Based on the research design, the sampled subjects were appointed by a third party to participate in the interview, contacted, and recruited using the snowball technique based on their social network. The grandfathers were informed about the research objective and then asked to schedule an interview if they met the inclusion criteria. On the day of the interview, the participant was given more information and any doubts were clarified. In what concerns data confidentiality, participants were ensured that the information collected would only be accessible to the researchers and that they would remain anonymous. Both the researcher and the participant were asked to sign the informed consent form. After data analysis, it is not possible to identify the participants, thus meeting the ethical principles of participants’ respect and anonymity.

3. Results

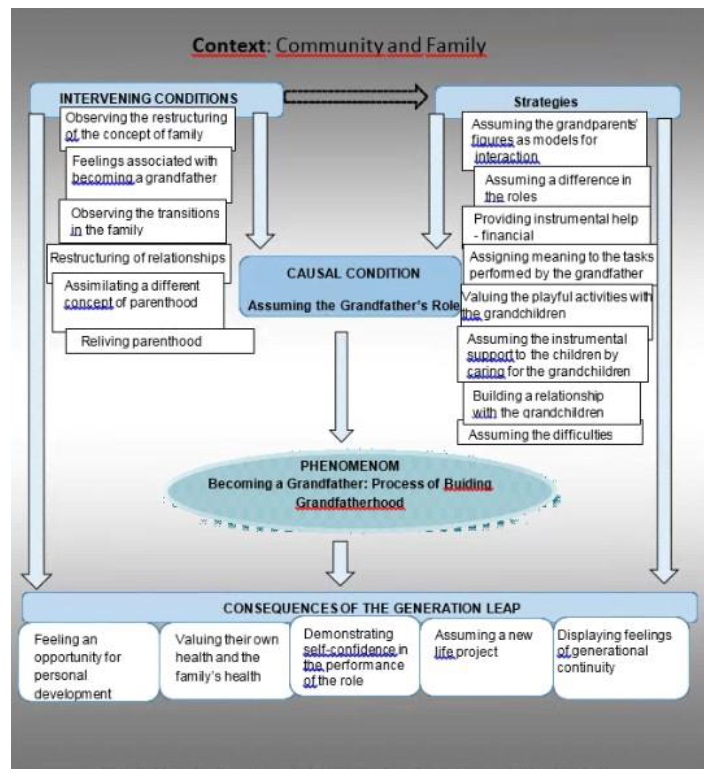

The diagram in Figure 1 describes the categories involved in the process of transition to grandfatherhood. In the upper part of the figure, and encompassing the whole diagram, is the community and family context where the phenomenon occurs. The causal condition - assuming the grandfather’s role - triggers the central phenomenon - becoming a grandfather: the process of building grandfatherhood - which in turn triggers the consequences of the generational leap. Both the intervening conditions and the strategies are, directly or indirectly, linked to the phenomenon and the consequences.

The context of the study is the particular set of circumstances in which strategies are taken, that is, where the phenomenon occurs. This study about grandfatherhood considered the community and family context where the transition process occurs. In the community where they are inserted, in their district, municipality, city, family, grandfathers assume the grandfather’s role, undergoing the process of transition to grandfatherhood. This study was developed in the central region of Portugal in seven municipalities of three districts: Aveiro, Coimbra, and Viseu.

The category assuming the grandfather’s role emerges as a causal condition, which seems to trigger the phenomenon. Grandfathers assume the role during pregnancy or the birth of their grandchild, when they face a new situation and experience grandfatherhood, or even before conception, when they imagine how their grandchild will be.

Data analysis revealed the intervening conditions that facilitate or hinder the potential impact of the causal condition on the phenomenon under study. Through the experience of grandfatherhood, grandfathers observe the restructuring of the concept of family. The presence of grandchildren generates inevitable changes in the family dynamics: they either bring the three generations closer, increasing the family’s unity and restructuring the family relationships, or increase the distance within the family. The grandfathers observe that, despite the same degree of kinship, maternal and paternal grandfathers have different levels of proximity. Both grandfathers and grandchildren end up being mediators in family relationships. The grandfathers expressed positive feelings and emotions in the category feelings associated with becoming a grandfather. Becoming a grandfather seems to be an expected and natural experience, but also a unique and enriching one. Blood ties do not seem to be as relevant, and the joy and happiness of becoming a grandfather are emphasized in experiencing a different type of love. Another category of the intervening conditions was observing the transitions in the family. The grandfather and his partner/wife undergo a process of transition to grandparenthood at the same time, helping each other. Moreover, their sons/daughters-in-law and daughters/sons-in-law are in a process of transition to parenthood. Thus, the grandfather has the opportunity to assist them with this transition already experienced by him. In relation to the category restructuring of relationships, the relationships with friends, extended family, and colleagues are restructured. Spending time with the children, grandchildren, children-in-law allows grandfathers to assimilate a different concept of parenthood, noting the differences in education and parenting. Grandchildren seem to give grandfathers the opportunity to reassess their experience as parents, relive their experience of fatherhood, and experience things with their grandchildren that they had not experienced with their children, reliving fatherhood.

Men use different strategies to deal with the fact of becoming grandfathers. In this transition, they consider the representation of grandparents as role models of interaction. These role models can be based on their own grandparents or parents, friends, colleagues, or even their partner/spouse, who is experiencing a similar transition process. The grandfathers assume the difference in roles in their process of transition to grandfatherhood, acknowledging the differences in the relationships of father and grandfather, and reconciling the different roles. In addition to the instrumental help in caring for the grandchildren, grandparents provide instrumental - financial help, that is, they contribute economically to the lives of their children and grandchildren and consider them as one of the reasons why they work. Grandfathers feel they teach and learn with their grandchildren. They may consider their role in their grandchildren’s education as similar to those of parents, see themselves only as support to their grandchildren’s education, or lay this task on their grandchildren’s parents, thus giving meaning to the tasks performed by the grandfather. In the strategies, the grandfathers seem to value the playful activities with the grandchildren, sharing with them these playful moments and learning at the same time. Assuming the instrumental support to their children in caring for the grandchildren emerges as another strategy in which grandfathers have to combine their will with social desirability, make themselves available to care for the grandchildren, and provide instrumental help to their children in terms of childcare (food, hygiene, comfort, safety, sleep, and transportation). The grandfathers build a relationship with their grandchildren. In this relationship of affection and love, different and reciprocal, grandfathers and grandchildren share the same interests and establish a friendship in which the grandchildren often receive gifts. Becoming a grandfather can trigger several difficulties - and grandfathers assume these difficulties: they may have to deal with their grandchildren’s absence; they may feel guilty for not being always available; the grandchildren and pregnancy can become one of their concerns; they can feel inexperienced or have difficulties in caring for their grandchildren. Grandfathers recognize the difficulties in transitions and develop strategies to overcome them. From their perspective, one of the difficulties is associated with technology which can impair these relationships.

The events that result from the phenomenon are called consequences. In this case, they are called consequences of the generation leap because they are a result of the increasing number of generations of a family. This occurs because a causal condition - Assuming the Grandfather’s Role - triggers a phenomenon - Becoming a Grandfather: Process of Building Grandfatherhood - and this process may result in consequences due to this generation leap. With the arrival of the grandchildren, a two-generation family becomes a three-generation family, with all the changes that this entails. One of the consequences of Becoming a Grandfather: Process of Building Grandfatherhood is that grandfathers feel an opportunity for personal development, assuming the transition to grandfatherhood as a learning experience and a change in their lives. Valuing their own health and their family’s health is another consequence of the generational leap, in which grandfathers assume grandfatherhood with a healing perspective: they become concerned with their own health, the health of their grandchildren and their family; develop strategies to improve health; and acknowledge the importance of health professionals. They demonstrate self-confidence in the performance of the role, resulting in a positive assessment of grandfatherhood. They conclude that being a grandfather is something enjoyable for everyone and express pride in their grandchildren. They feel a sense of accomplishment in the performance of this role and reveal that being a grandfather is easier than being a father. In becoming a grandfather, they assume a new life project in which they project their life, the life of their family and their grandchildren. And although they feel like they are getting older, they also feel rejuvenated with grandfatherhood. Grandfathers experience a sense of continuity in their grandchildren, pass on values, and are responsible for keeping alive the traditions and memory of the family history, expressing feelings of generational continuity.

Figure. 1 Diagram explaining the phenomenon of Becoming a Grandfather: Process of Building Grandfatherhood

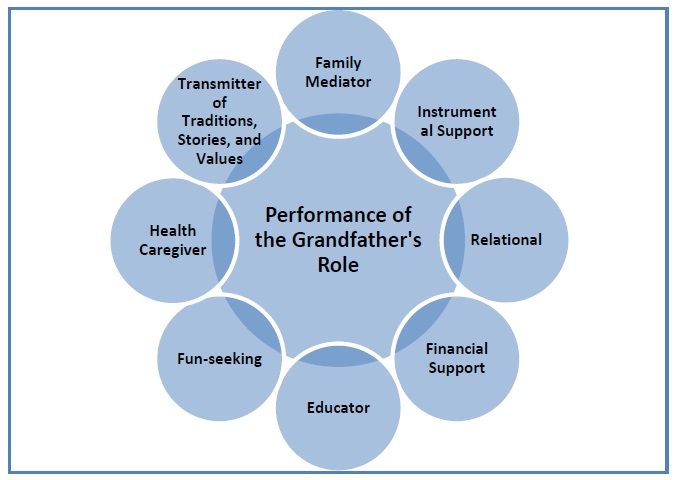

Figure 2 shows the different roles of grandfathers in family health. When he becomes a grandfather, the man, who is already a son, husband/partner, father/father-in-law, friend, colleague, takes on one more role in society - the grandfather’s role in family health, involving different tasks within the community and the family unit.

By becoming a grandfather - Becoming a grandfather: Process of building grandfatherhood, and as a consequence of the transition to grandfatherhood, he plays the grandfather’s role. This fact can be seen in the causal condition when the man assumes the grandfather’s role. Men adopt different behaviors that distinguish their role as grandfathers from other roles such as those of fathers or husbands. The grandfather’s role was described by the grandfathers in this study as a distinctive role. In the category Assuming the difference in roles, the grandfathers mentioned the distinction between the various roles and the reconciliation of those roles.

The intervening conditions include the category observing the restructuring of the concept of family, in which the grandfather emerges as a mediator in the parents-children relationship, giving rise to the role of family mediator. The grandfathers’ privileged position between parents and children gives them a power of mediation within the family regarding conflict resolution or even to maintain family stability.

With regard to the strategies, men play five roles as grandfathers.

The instrumental support role is the help that men provide to their children in caring for their grandchildren, namely regarding food, hygiene care, comfort, and safety, and is justified by the category assuming the instrumental support to children in caring for the grandchildren.

Another role is the financial support role, in which grandfathers provide financial support to their children and grandchildren, presented in the category providing instrumental help - financial. Although it could be integrated into the instrumental support, it stood out because of the importance assigned by the grandfathers in the performance of the grandfather’s role.

Grandfathers describe the relationship with their grandchildren as being different from other relationships. This relational role was widely described in the category building a relationship with the grandchildren.

In the category giving meaning to the tasks performed by the grandfather, grandfathers also play the role of educator, collaborating with their children in their grandchildren’s education.

Grandfathers also highlighted the fun-seeking role as an enjoyable task (valuing the playful activities with the grandchildren). The sharing of moments of fun and learning is reflected in the relationships between grandfathers and grandchildren. In the performance of his role, the grandfather assumes the role of health caregiver in providing care to the family. Although it may not seem very visible, this role is evidenced in the consequences of the generation leap, namely in the category valuing his health and his family’s health. The consequences of the generation leap include the category expressing feelings of generational continuity, which justifies the grandfather’s role as a transmitter of traditions, stories, and values. Grandfathers are responsible for telling personal and family stories that preserve the family’s history. They can be seen as a role model for the family’s values and traditions.

4. Discussion

Discovering the main variable is one of the goals of Grounded Theory. This variable will often be present in the data and relate the various data. Being central, it explains data variation; it has applications for a theory; as the variable becomes more detailed, the theory becomes more consistent, allowing for maximum variation and analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 2008). Thus, the use of Grounded Theory to explain the phenomenon Becoming a Grandfather: Process of Building Grandfatherhood was essential, exploring an underexplored nursing-sensitive area, enabling nurses to plan interventions for facilitating a healthy transition for grandfathers and avoiding unhealthy transitions that impact negatively on their health and well-being.

The phenomenon occurs in the community and family context, within family health, and it is where men experience the transition to grandfatherhood. These conditions may facilitate or hamper the whole process. The family is the ideal place for the development and coexistence of intergenerational relationships, the transmission of values, and the provision of support, protection, and care to the family members (Tarallo, 2015).

The increasing possibilities of interaction between different family generations in current societies also mean that these relationships tend to become more meaningful (Tanskanen & Danielsbacka, 2019).

The major transitions of the life cycle, such as the transition to grandfatherhood, are, by nature, stressful events, but are also excellent opportunities for personal development (Taubman - Ben-Ari & Shlomo, 2016). The transition to grandfatherhood brings about a change of status, roles, and identities, and is perceived by the grandfathers as one of the most significant and emotional events in their lives (Noy & Taubman-Ben-Ari, 2016).

Grandfathers feel a sense of renewal. They have the opportunity to do things differently from how they did as parents (Daró, 2018) because the transition to grandfatherhood is less dramatic than the transition to parenthood (Taubman - Ben-Ari & Shlomo, 2016). The grandfathers’ dedication to their grandchildren, giving them exaggerated attention, is a way of redeeming themselves from the guilt felt in relation to their children (Dias, 2002).

Grandfathers who care for their grandchildren feel accomplished in performing this role, both emotionally, expressing feelings of happiness or joy, and cognitively, reporting that this role has a positive effect in their lives (Triadó, Villar, Solé, Celdrán, Pinazo, & Conde, 2009).

Louzeiro and Lima (2017) argue that becoming a grandfather is not a matter of choice; spending time and developing a bond with the grandchildren impose a unique responsibility on grandfathers and the need to distinguish the roles of father and grandfather in this relationship with the grandchildren. This experience of grandfatherhood is not consistent with the responsibility that they had while raising their children because grandparents are not supposed to educate, but rather to transmit knowledge. However, grandfatherhood seems to strengthen the psychological well-being of men, being an opportunity for self-realization and understanding of their purpose for living (StGeorge & Fletcher, 2014).

Grandfatherhood is unique and gives meaning to time, on the one hand, as a restructuring unit of the past and, on the other hand, as an expression of future projects. Grandfathers take on a new life project as a result of the transition to grandfatherhood; they plan their future, the future of their family and, in particular, of their grandchildren.

In relation to the grandfathers’ role, Azambuja and Rabinovich (2017) consider that the grandfathers’ experience in raising children helps them to provide emotional and instrumental support, in particular to their grandchildren. Focusing on the performance of the grandfather’s role, the grandfather plays his primary role as a man. His secondary roles include being a partner, a father, and a grandfather. The male participants in this study display certain instrumental and expressive behaviors that characterize their grandfather’s role, such as the role of family mediator, the role of instrumental support, the relational role, the role of financial support, the role of educator, the fun-seeking role, the role of health caregiver, and the role of transmitter of traditions, stories, and values. These roles can be compared to the grandparents’ roles defined by Sapena, Desfilis, and Seguí (2001).

The phenomenon of grandfatherhood transcends the transition itself because the grandfather has a prominent place within the family to promote family health.

Conclusions

The transition to grandfatherhood implies that men in their family and community contexts are aware of the process of becoming grandfathers. This happens when they, consciously, assume the role of grandfathers, marking the beginning of this process either through childbirth, pregnancy, or even earlier, in their desire to have grandchildren. This new situation and the experience of grandfatherhood is conditioned by each male’s concept of grandfather. It may be a situationally different moment for each individual, but assuming the role of grandfather marks the beginning of the whole process. At that moment, men assume that the process is irreversible and that they need to cope with a new imminent situation - the experience of grandfatherhood. When they become grandfathers, men develop strategies for dealing with grandfatherhood that are closely linked to the phenomenon experienced, the causal condition, and the consequences. These strategies promote the healthy transition to becoming a grandfather and are used to combine the tasks within each role. This process of construction brings about certain consequences that are incorporated by men. Becoming grandfathers restructures their personal and family lives.

Regarding the grandfather’s role within family health, the grandfather plays a number of tasks with a view to maintaining family health, such as the role of family mediator, the role of instrumental support, the relational role, the role of financial support, the role of educator, the fun-seeking role, the role of health caregiver, and the role of transmitter of traditions, stories, and values.

The transition to grandfatherhood occurs when the whole family is in a period of transition. Thus, it is important that the family health team draws up a care plan involving the whole family, facilitating the transitions in progress. The knowledge about the grandfather’s role, in clinical practice, helps the nurse to formulate nursing diagnoses and, consequently, plan interventions for the grandfathers and the families who are undergoing an unhealthy transition to grandfatherhood, with an impact on their health and their families, as well as promote a healthy transition. One of the limitations of this study was the generalization of results. This is usually a limitation of the studies using the Grounded Theory approach because, although its purpose is essentially to explain phenomena, the aim here is to produce an explanatory theory, rather than to make generalizations. One of the ways to overcome the criticisms to the methodology was to strictly follow the research design