Introduction

Clinical supervision (CS) is a formal process involving a senior professional who supervises and guides the clinical practice of less experienced professionals, aiming at professional development, promotion of quality of practice, and client’s safety and protection, through processes of reflection and analysis of practices (Snowdon, Leggat, & Taylor, 2017).

Evidence has shown that CS of health professionals is associated with the effectiveness of care, increased improvement in the care process and quality of care (Snowdon et al., 2017; Guy, Cranwell, Hitch, & McKinstry, 2020).

Improving the quality of care depends on individual growth and team development. Several strategies mobilised by CS in nursing are important contributors to achieving these goals, namely the reflexive practice, which involves a critical assessment process of learning and development needs, understanding of professionals' attitudes, beliefs and values, integrating learning and practical knowledge into clinical practice (Gates & Sendiack, 2017).

Despite current evidence suggesting the potential of CS in nursing to improving quality of care, this can only be attained through the professional reflexive and responsible attitudes. Hence, the relevance of the CS in nursing involving a structure and a process underpinned by the principles of reflexive practice, aiming to promote the critical capacity of the supervised. This is an important factor to master professional reasoning and decision-making skills (Gates & Sendiack, 2017; Guy et al., 2020).

This study is part of broader research aimed at identifying current CS practices.

1. Review of the literature

The underlying importance of the reflexive processes in nursing was first developed by Florence Nightingale. Until then, nursing was more viewed as a form of art rather than science. The modern concept of the profession related to the technological and scientific advancements starts to materialize with the industrial revolution.

In nursing and other professions, the focus on technique has endured for centuries, struggling between the dominance of technical thinking to critical reflexive thinking. Importantly, the role of John Dewey and Donald Schön viewed as the main precursors of reflexive thinking, which ultimately led to a solid model beginning in the 1990s.

Dewey was one of the first authors to identify reflection as a specialised way of thinking, triggered by doubt, hesitation or perplexity when experiencing a situation leading to purposeful self-questioning and problem-solving. The author also argued that reflexive thinking leads people to think beyond routine/action guided by tradition or external authority (Dewey, 1933). However, his work was subject to some criticism since it was considered to be a linear and mechanistic approach, with no real understanding of reflection as an interactive or dialogical process, lacking attention to the way the "self" and individual references are also substantially important to dialogue (Cinnamond & Zimpher, 1990).

From the beginning of 1880s Schön's studies on the processes of training the "reflexive professional”, influenced by Dewey, were already a reference, arguing that the training of the future professional should include reflection based on real practical situations. This is extremely important to develop professional abilities to face new and different challenges posed in real life and make the best decisions when dealing with uncertainty (Schön, 1987).

Other fundamental notions of Schön's work (1987) refer to knowing-in-action, reflection-in-action, reflection-on-action and reflection on reflection-in-action. Schön core assertions for vocational training also refer to the distinction between tacit knowledge, identified as reflection-in-action, and academic knowledge. Duarte (2003) problematizes the epistemological and pedagogical assumptions found in Schön opposite types of knowledge. Also, Duarte argues Schön adoption of a pedagogy that overlooks school knowledge and an epistemology approach that disregards theoretical/scientific/academic knowledge, referring "...the disregard for theoretical knowledge is present in several authors who have become a reference in the field of teacher training studies", also placing Dewey, Tardif and Perrenoud (Duarte, 2003, p. 602) at the centre of this debate.

Considering Zeichner (1993) assumption that reflection is the act of thinking in a critical-constructive way capable of building knowledge, it is important to understand that "learning is not attained through practice: it is through reflection on practice!". This exercise requires the mobilization of scientific knowledge to frame a learning environment so that professionals continue to learn and develop "within" and "through" practice.

Each stage of the reflection, reflection-for-action (before action, intended to planning), reflection-in-action (interactive, reflection by observing and discussing the situation), reflection-on-action (post-active, with a retrospective and prospective approach), or reflection on reflection-in-action, needs an underlying theoretical reference, an academic/scientific knowledge, a "lived history", in conceptual terms. These are important contributors to reflection for-, in- and on- action that help incorporate the retroactive (retrospective) and proactive (prospective) dimensions, allowing reflection on a new action, controlling the previous negative outcomes (Sá-Chaves, 2000).

The systematic conceptualizations related to health, social, scientific and technological advancements have demanded nurses’ additional abilities to continue personal and professional adaptation and growth, with inherent reflexive processes. These processes are likely at the baseline of the recognition of nursing as a knowledge discipline, autonomous and with its field of intervention.

Reflection is determinant for nurses’ mastery, from beginners to experts, these later identified as expert reflexive, characterized by non-guided professional practices or models.

It is widely accepted that the challenges of the profession require responses that must consider reflexive processes and the (re)conceptualisation of practices. This is imperative to meet the need of implementing nursing CS policies with a strong reflexive component, considering the importance of providing opportunities for reflection among peers.

In particular, the policies of national and international bodies, namely the UK Department of Health and the Order of Nurses, are embedded with arguments for increased reflexive practice and professional development, highlighting the role of CS in nursing for ensuring high-quality care standards through reflexive processes.

Rocha (2013) concluded that the critical-reflexive analysis of practices was the fifth most implemented and most desired CS strategy in health services. Also, this was found the most relevant strategy in the study conducted by Pires, Pereira, Reis Santos & Rocha (2016), among the 16 CS analysed strategies.

2. Methods

In line with the research goals, a qualitative, exploratory study was developed, anchored in the constructivist paradigm. The research was guided by the principles of action-research focused on the interaction between context and participants, allowing an in-depth analysis of the phenomenon CS in nursing, its complex nature and underlying processes, cardinal to the meaning, understanding and interpretation of this problem and relying on the participants' perceptions.

2.1 Sample

A convenience sample of 42 nurses recruited from three Health Centres (HC) of a Health Centre Grouping in the northern region of Portugal was used, intended to involve all nurses working in these health units.

All nurses from the Personalized Health Care Units of the health centres involved in this study were willing to participate. Participants were mainly women (85.71%; n=36), aged between 28 and 59 years (M=44.19; PD=7.43), time of professional experience between 6 and 40 years (M=20.27; PD=7.21). Graduate nurses and specialist nurses were the most prevalent professional categories found (42.86%; n=18).

2.2 Data collection

The data collection was carried out through a semi-structured interview including a script with five major themes: the first theme addressed ethical considerations and the study proposed objectives; the subsequent themes included questions related to the conceptions, representations and opinions of the participants about CS in nursing.

2.3 Data analysis

The interviews were recorded on audio and transcribed in full as they were conducted. The Nvivo10® program was used to codify each interview. Content analysis was carried out according to the principles of the grounded theory method (Strauss & Corbin, 2008). After the analysis of each interview, fieldwork was done whenever deemed necessary to validate the information.

Ethical considerations

Ethical consent was granted by the Ethics Committee for Health of the Northern Regional Health Administration and the Board of Directors of the Health Centre Grouping involved.

All participants signed informed consent, and anonymity and confidentiality were ensured in data analysis and processing.

3. Results

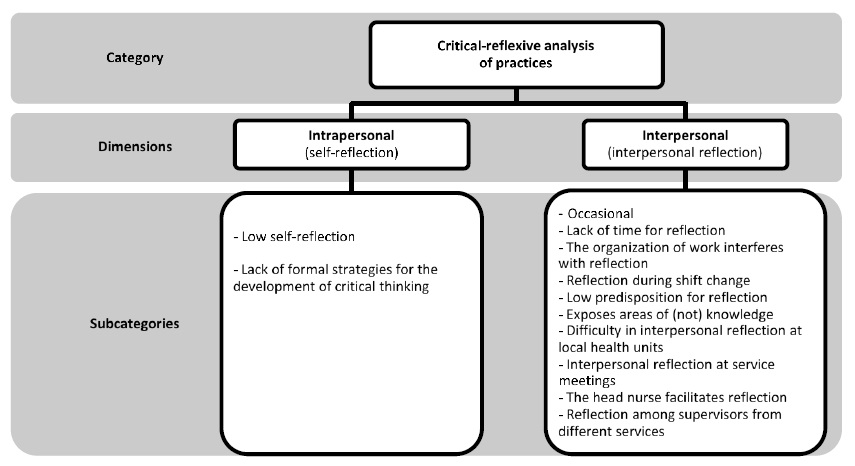

From the analysis, the category "Critical-reflexive analysis of practices” emerged, which refers to one of the current CS strategies, with identified dimensions and subcategories (Figure 1).

The dimensions identified were the intrapersonal dimension - from which the subcategories low self-reflection, and absence of formal strategies of critical thinking development emerged -, and interpersonal dimension - from which emerged the subcategories occasional, lack of time for interpersonal reflection, organisation of work interferes with interpersonal reflection, the difficulty of interpersonal reflection in health units exposes areas of (not) knowledge, low predisposition to interpersonal reflection, head nurse facilitates interpersonal reflection, interpersonal reflection at service meetings, and reflection between supervisors of different services.

4. Discussion

Support on reflection facilitates the integration of knowledge, especially at the early stage of professional development, in which often nurses have not the necessary skills to engage in effective critical-reflexive thinking. It is crucial to access knowledge and peer experiences to deepen self-knowledge and thinking. Hence, the relevance of empirical knowledge and the sharing of practices of experienced professionals are highlighted. The clinical supervisor and experienced colleagues are the main responsible for providing this support.

4.1 Intrapersonal dimension

This critical-reflexive analysis dimension refers to individual reflection, consisting of an intra-personal component identified by Schön (1987) as the "silent game", a reflexive process compared to an individual "solitary game", of a dynamic feature that generates unpredictability, underlying the fascination for problem-solving. Contrarily to this dynamic is the opinion of one of the participants, who perceived some "routine" installed in the service likely related to the lack of intrapersonal reflection, questioning and problematization of practices, meaning little self-reflection:

(...) it turns out that the majority of us are already accustomed to current practices (...) we got used to the routine, to perform all those tasks without reflecting much on what we do. Is there anyone who at the end of the working day (...) reflects or questions his or her day-to-day work? Is there anyone? I don’t believe so! E9CH

This result corroborates the findings of Netto, Silva & Rua's (2018, p.2) that "technical reasoning mindset, normative curriculum, application of theory and technique derived from mainly systematic scientific knowledge, the epistemology of practice, and the still existing gap between teaching, research and practice, mostly in universities, leave no space for reflexive action and hinder professional competence".

This metacognitive capacity is vital since it allows nurses to become aware of the processes underlying their professional activity. Thus, the guided reflexive practice in CS promotes introspection, stimulating critical-reflexive thinking about clinical experiences and underlying scientific evidence (Gates & Sendiack, 2017). The reflexive practice is important because it is a specific working method, intended to allow the professional to build knowledge based on his/her practice. This method is defined as the "art of intrinsic growth" through reflection, with the purpose of finding a solution (Netto et al., 2018).

Regarding the absence of formal strategies for the development of critical thinking (…) there's a more informal strategy for the development of critical thinking. E16VP

The study by Dubé & Ducharem (2015) showed that the working culture of some health units does not encourages reflexive nursing practices. Gates & Sendiack (2017) noted that a reflexive environment provides the opportunity to reflexive thinking within the supervisory context, allowing supervisors to meet both the supervised and the client’s needs. It also provides a solid structure that facilitates reflexive practice, supports the development of technical skills and critical thinking, and ultimately encourages the development of personal and professional identity. The same authors argue that the existence of a formal reflexive environment within the organisation promotes a sense of conscious introspection of professionals allowing the development of mastery of practice over time, including ethical considerations and clinical wisdom.

4.2 Interpersonal dimension

The interpersonal dimension of critical-reflexive analysis refers to hetero-reflection, a dyad reflection carried out within groups, which Schön (1987) identified as the “interplay", implying an attitude of intellectual humility, recognizing that "the other" can substantially improve our knowledge.

The participants identified the presence of reflexive practices among peers:

We engage in reflection among colleagues! Well, some are more engaged than others! But we share information and knowledge (…) E2RP; (…) we discuss our patients’ cases daily and the experienced difficulties. (...) not only with colleagues but with supervisors. It seems to me that we already do some supervision work. We talk about things that go well and those not that good, discuss situations where we could be more committed and why this doesn’t happen sometimes. E5RP

However, they consider that interpersonal reflection is occasional, non-formal:

(...) it happens occasionally. We have no specific moments for that. E13CH; Sometimes, when we’re faced with a new situation, that someone else has already experienced, we sit down and discuss it informally. E14VP; I really think we already do that informally. E4RP

Also, Tavares (2013) concluded that the nurses recognized the existence of critical-reflexive analysis practices in their services, despite its informal character. However, they considered that reflexive processes including the sharing of knowledge, experiences, and points of view among colleagues resulted in individual and collective enrichment, ultimately benefiting the client by developing action strategies discussed and reflected among peers. However, Süleyman & Bozkuş (2017) argue that being reflexive should constitute a vital component of daily life, not a separate and unrelated action from practices.

Despite the informality in implementing this CS strategy, Rocha (2013) concluded that this was the fifth most frequently implemented in health services. However, this strategy emerged in the sixth position concerning the willingness of frequency to adopt it.

In view of the difficulties expressed by participants in finding time for reflexive analysis of practices among peers, the subcategory lack of time for interpersonal reflection emerged:

(…) The problem is having time for that, (…). Lately, we haven’t had the opportunity to share and reflect on our practices, and we used to have it (…). We have fewer opportunities for reflection among us. E8CH; I would really like to have more time! E5CH

Time is a factor that can influence the conditions for reflexive analysis of practices, and informality seems also to hinder this factor, "leaving matters for a later discussion", and overlapping tasks considered "more important".

The studies conducted by Cross, Moore, Sampson, Kitch & Ockerby (2012) and Tavares (2013) also showed that the CS in nursing is particularly important in services where nurses are more affected by work overload, so time should be provided to reflect on their practices and professional issues.

CS is based on reflection since the whole supervisory process is only relevant because it integrates reflexive processes, so the provision of time for CS in nursing and related training must inevitably include time for reflection on practices and contexts (Dubé & Ducharem, 2015; Snowdon et al., 2017).

Another emerging aspect pertaining to reflection was the organisation of work, the subcategory - organisation of work interferes with interpersonal reflection, which somewhat relates to the previous one:

We often don’t have the opportunity to reflect with each other on practices because we´re working isolated, in separate stations. E11CH; There is little sharing! (…) our organization of work doesn’t help! E1CH; (…) it also depends on the department and schedules. There are days (…) we discuss some things. But then, this colleague works until seven, the other until five... or is alone on that shift (...). Meaning, we´re aware of what our closest colleague id doing, (...) and that’s whom we talk with. (…) we would have to organize! (…). E2CH; (…) The organization of work doesn't leave much space to discuss things with all our colleagues. (…) I think this is mostly due to the organization of work. E4RP

Süleyman & Bozkuş (2017) state that the reflection promoted by an organization's culture and structures affects and is affected by choices, policies, decisions and work.

The participants also referred to the shift change as a privileged moment for reflection on practices. They also consider that nurses highly benefit from the time provided by the organisation of work to engage in discussions about the client’s condition and the provision of care, and thus a new subcategory emerged - reflection during a shift change:

We have less time to reflect. It's not like in the hospital, every day, during shift change (...). E1CH; (...) I know that in some hospital services and other health centres this is possible during shift change, but here we don’t have that time. (…) we really need to talk more about care. (...) we haven’t that kind of meetings. Sometimes we’re not able to discuss things, and this is important. E4CH

These perspectives corroborate the findings of Tavares' (2013), which identified daily practice situations conducive to reflection, individually or collectively, highlighting the importance attributed by participants to analysis, discussions, and reflections that took place during shift change considered cardinal for the development of reflexive practice. Shift change is highlighted as an important time to reflect on practice and assess the best strategy for a specific situation, emphasizing the shared and discussed information.

Rocha, Reis Santos & Pires (2017) also concluded that hospital nurses reported more sharing opportunities, particularly at shift change.

Another identified sub-category points to the influence of individual characteristics that the participants recognised in some colleagues, which may condition reflection - low predisposition for interpersonal reflection:

Some colleagues make reflection more difficult. (...) it's no use... because then he insists that he’s right. Some colleagues are not open to discussions, so they always think they’re right! (…). I’m not sure they understand they’re missing out the opportunity of learning with colleagues! They think they’re always right. E1VP; Some find it more difficult to ask colleagues for an opinion about the provision of care! (…) some colleagues find reflection more difficult! (…) the most conservative colleagues find it more difficult to discuss provision of care among colleagues. E3VP; (…) there’s always someone that doesn’t enjoy doing it! Isn’t it? E5CH

According to Sá-Chaves (2000), the transition to the "solidarity self" is not easy. The difficulty of reflecting openly with the other can be rooted in personality traits/communicational skills, lack of time and other personal or organizational constraints. Despite the attenuating effects of the lack of a reflexive "culture" underpinned by paradigmatic issues, its marked influence until the 1980s somehow seems to linger.

In the study conducted by Pires (2004), reflection on practices among nurses was mentioned as one of the daily socio-clinical difficulties, namely some resistance to reflexive practice. Some professionals considered they had universal truth, unwilling to discuss it with their colleagues.

Also, the subcategory - exposes areas of (not) knowledge has also emerged. The participants perceived that the knowledge deficit could be identified through interpersonal reflection:

I ask for my colleague’s opinion on knowledge, to see if I’ve got the correct information. They help me understand if I’ve sufficient knowledge. E13VP

This finding is in line with the work developed by Süleyman & Bozkuş (2017), who considered interpersonal reflection a way of learning, and a "double-loop", a process of shared cognitive learning. The participants helped each other identify difficulties and find targeted strategies, thus broadening their perspectives on problem-solving (expanding knowledge) and acquiring new insights into behaviour (change of attitude).

The difficulty of interpersonal reflection in health units was also mentioned, which stems from the lack of discussion among peers, also due to the more isolated working characteristics:

(...) we’re physically distant from the main services, so it’s more difficult to engage in reflection with colleagues. E9VP

The geographical distance between health units and the main unit was identified as one of the factors hampering CS and peer reflection, adding to working places with a single nurse. This finding corroborates the study by Rocha, Reis Santos & Pires (2016), suggesting the existence of contexts where direct contact between professionals is difficult due to geographical distance, particularly between colleagues and/or supervisor and supervised. This particular situation hinders the supervision process and reflection and often suggests implementing CS strategies at a distance.

Studies involving environmental, demographic characteristics showed significant differences in the organisation of CS in hospital and community contexts, precisely due to the greater dispersion of professionals in the second context (Lynch, Hancox, Happel & Parker, 2008).

Although the participants identified some difficulties and informal/occasional reflection of practices, they pointed out the benefits of service meetings, more formal programmed moments, thus emerging the subcategory - interpersonal reflection at service meetings:

We all take advantage of service meetings to reflect on care provision and ask some questions. If we have some difficulties we share them with colleagues and try to clarify them (…). E11CH; We engage in reflection among us. We try to! Usually we go to meetings and take this opportunity to be with colleagues from the main unit and discuss strategies. E11VP; We share opinions and discuss care provision at our meetings. We already do that! (…) we have these meetings to share our doubts. Sometimes it´s good to disagree! E13VP; We always reflect on care and clinical records at monthly meetings. E15CH

The relevance of reflection to the progressive improvement of nursing care provides nurses with the opportunity to reflect on their practices in meetings held exclusively for this purpose (Cross et al., 2012; Tavares, 2013).

Reflection among supervisors of different services was another identified subcategory.

There is some solidarity between colleagues, (from different CS) and peers with the same role [supervisor], we share and help each other. E7RP

The study of Cruz (2012) also highlighted the reflection between supervisors of different services through "indirect supervision" through team meetings of clinical supervision, intending to share information and standardise their actions. Borges (2013) found that participants stressed the importance of supervisors' meetings as they provide a greater support level.

Another subcategory identified was - head nurse facilitates interpersonal reflection:

(...) the head nurse provides us with the opportunity to meet with each other and share experiences. E7VP; I always encourage interaction in meetings. (...) I encourage the team's reflection and critical thinking. E15CH

The study by Pinto, Reis Santos & Pires (2017) showed that the supervisor plays a pivotal role in training reflexive professionals by mobilising targeted strategies. Since Portugal does not have formal CS programmes implemented in health services, it is assumed that the head nurse plays this role. In the study conducted by Tavares (2013), the head nurse was found to have a relevant role in stimulating the critical-reflexive analysis of practices, encouraging the nursing team to reflect for-, in-, and on-action, and in the performance as a supervisor, acting as a catalyst for reflexive practice, focusing on improving care. The nurses considered that the team mirrored their leadership, concerning reflection, because their demand impelled the team to become more demanding, making them accountable for self-development and encouraging professional accomplishments.

Süleyman & Bozkuş (2017) considered that reflection is a way of learning and that its management is an essential goal in creating reflexive teams, aiming to provide strong and equitable learning opportunities for everyone within the organisations, and encourage benefits from these opportunities. In this sense, they understand that managers can contribute by committing themselves to focus on learning, training professionals and developing ways of overcoming inquiring skills to develop mental behaviours for additional and autonomous learning.

Conclusion

This study allowed to identify a set of current supervisory strategies to promote professional development and quality of care, namely the critical-reflexive analysis of practices. Several important constraints of individual and contextual nature were identified that hinder the operationalization of this strategy, which need to be overcome.

Critical-reflexive analysis of practices is crucial to stimulate knowledge, critical thinking and decision-making, therefore, clinical supervision policies in the context of primary health care must integrate reflexive strategies.

Despite the similarities of these study findings with other contexts, this study is limited in the generalisability of data.

Thus, future research is encouraged in the scope of reflection, critical thinking and nursing decision-making, involving the individual and contextual factors that facilitate/hinder the development of reflection.