Introduction

Public administration responds to the needs of vulnerable children with the resources that are available in the protection system. Family is the natural element, and parents, mothers and other guardians are the most important elements to promoting child well-being and are responsible for the care and protection of the youngest.

The State assumes the co-responsibility of ensuring that the best interests of child are respected, and acting when the responsible adults do not adequately perform their functions.

We are facing a mixed system in which the private sphere, typical of the family entity, is the main responsible for care, but the public action of the State acts as a guarantee in case of needs or neglect in these family care functions.

Sociocultural factors determine the response that society gives to the needs of children and adolescents. In the Iberian Peninsula, are share social values based on a social imaginary that suggests as an unquestionable principle the fact that the family takes care of their children. In both countries, the family is the natural environmental that support children development. This article attempts to carry out a comparative analysis of the public response that the protection systems of Portugal and Galicia have developed to face the most vulnerable situations. In Spain, the autonomous communities are responsible for the child welfare system/child and adolescent protection. The state develops the normative base, but it is the autonomous governments that carry out the protective action and develop their own legislative framework. It was used official publications from both states but the Spanish administrative organization forces us to use state statistics together with that of the Xunta de Galicia to compare the implementation of protective action in both territories. Galicia community is bordered by Portugal and a shared culture and social elements are present in this region.

In recent decades, it has increased the number of researchers that analyze the reality of child care resources in both states (Carvalho and Manita, 2010; Delgado and Gersao, 2018; Fernández-Simo and Cid, 2016; Mateos et al., 2017; Mota & Matos, 2008; (Pérez-García et al, 2019; Rodrigues, Barbosa-Ducharne, & Del Valle, 2003;). The protection system has become a complex framework. The complexity of the systemic framework lead us to focus our attention on aspects that we consider crucial for the quality of socio-educational action. In this article we approach the foster care measures, the school situation and the process of transition to adult life as factors of special incidence in the intervention. These aspects are considered by evidence as well as by international legal norms and in legal norms of both countries, as determinants in the social integration of children and in improving the situation of vulnerability, becoming reference indicators of the quality of institutional action.

1. Methods

It was used official information provided by the governments of Portugal, Spain and Galicia to analyse the reality under study. In Portugal,it was used the CASA 2017 report. The Spanish and Galician reality is analysed using the means of the statistics of Bulletin 20 and the regional statistics of the annual report of the Government of Galicia (Xunta de Galicia, 2018) and the official reports of the Mentor Programme (IGAXES, 2018). From the variety of indicators that are part of the statistics of both states, those referring to the protection measures adopted, the exits from the system and the educational pathways of adolescents in protection, are chosen. The selection of these indicators was supported by two external advisors specialized in child protection and that well known the reality of both countries. This process aims to give reliability to the indicators used.

2. Results

2.1 Measures

The total number of files in the Spanish protection system increased by 8%, from 43,902 in 2016 to 47,493 in 2017. The total number of files in the Spanish protection system increased by 8%, from 43,902 in 2016 to 47,493 in 2017. Residential foster care in Spain accounts for 37% of all care measures, compared to 87% in Portugal. Even so, the number of places occupied in Spain increased from 14,104 in 2016 to 17,527 in 2017. In 2017, a total of 7553 children were in Portuguese residential care. Generalist care has been decreasing since 2008 by 24%. Residential care specialized in intervention in emotional difficulties is increasing.

Host Families are decreasing in both countries, the most worrying situation being in Portugal, where this modality represents 3%, compared to 40% in Spain. Of the total number of assessments of suitability for host families, 53% are in an extended family and 47% in a third person. In Spain, 67% of these measures are formalised with extended family members, reaching 78.6% in the case of Galicia. Official Portuguese data show a 73% decrease between 2018 and 2017. The 246 minors in foster care in 2017 place Portugal in a scenario without comparison in Europe, being an underutilised measure. Galicia has 1,326 children in 969 families (Xunta de Galicia, 2018).

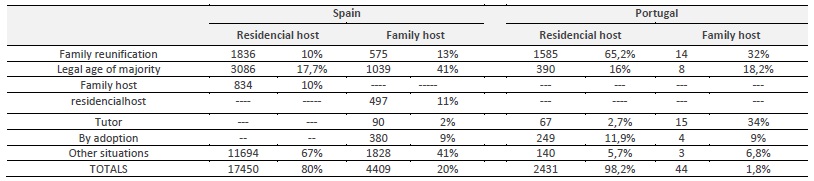

2.2 Exit of the protection system

In 2017, a total of 2857 participants left the Portuguese protection system. 49% of cases return to their nuclear family (1041), 15% return to the extended family (427) and 7% transitioned to independent living. Situation analyze in Galicia, show that most of the discharges from residential centers are due to family reintegration (26.6%), 13.4% go to host families and 17.3% due to legal age of majority. Although back into families of origin is the preferential option for adolescents under care (Table 1).

Table 1 Exits rates from the child protection system in Portugal and Spain

(Data prepared based on information from the Relatório Casa 2017 and the Boletin de Dados Estadísticos de Medidas de Proteción a la Infância de datos del 2017)

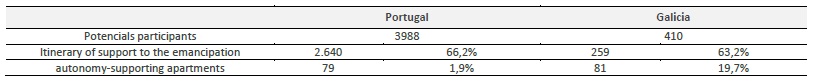

In Galicia, 36.61% of the young people in the emancipation programme achieved all the objectives agreed in their educational programme. In Portugal, in 2017, 31 young people left autonomy apartments. 23% went to rented accommodation and 26% to rented rooms. It is important to highlight that in the rest of the residential resources, the majority of the exit option has been return to the original family. The above data show that it is recommended that resources for the transition to adult life be developed to promote the overcoming of the difficult situation (Table 2).

Table 2 Participants with autonomy project and access to residential resources to support emancipation in Portugal and Galicia (2010/2017)

(Elaborated according to statistical information from Relatório Casa 2017 and Memoría Programa Mentor 2017)

In Galicia 63.17% of adolescents are in residential care, aged between 15 and 17, and are registered in the emancipation programme. 53% of Portuguese children in care situation are over 15 years old.)

In Table 3 is shown that the access of these young people to specialised residential support for emancipation is significantly lower in Portugal.

Table 3 Comparison between Portugal - Galicia of access of minors over 15 years old in residential care, to processes and resources to support emancipation.

(Prepared according to statistical information from Relatório Casa 2017 and Memoría Programa Mentor 2017)

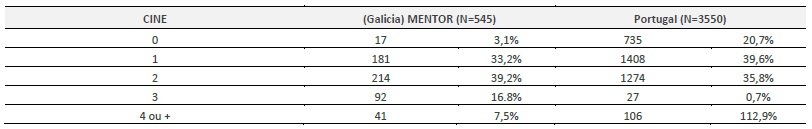

2.3 Educational trajectories of adolescents under protective measures

The International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED in English and CINE in Spanish) was used as a basis for comparing the academic situation in the two systems. As shown in Table 4, 33.2% of adolescents in the emancipation programme in Galicia do not have ESO (ISCEDII). Excluding the 33 files listed in the Mentor report in the "no record" category, corresponding to situations of intervention in an initial situation and with unrealised educational projects, the number of young people in ISCED reach 35.35%. The majority, 41.80%, would be in ISCED II. The Portuguese situation is similar, although the percentage of young people in ISCED I is slightly higher and the difference in ISCED 0 is notable.

3. Discussion

The Child Protection System in Portugal was subject to continuous legal changes around family care. According to Delgado and Gersao (2018), since the beginning of the 21st century, several institutional forums have been held in which the importance of reducing residential institutionalisation has been highlighted, with a focus on alternative options.

Recently, measures to promote family care were presented, framed in Decree-Law No. 139/2019 of 16 September. The legislative proposals are in line with international recommendations for the Portuguese Child Protection System that points to the reduction of residential care as a priority (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2014). The data analysed in this study show that the number of children in residential care in Portugal is significantly higher than in the Spanish protection system. Hoster families are an underutilised resource. The Host family concept is of particular interest for the future of child care systems but it is still not a common practice (Riggs, 2015), being a more effective (?) alternative for social protected children (Dozier et al, 2014; Van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Scott, 2015). Pitcher (2014) points out that host families promote a sense of belong and stability, and also recent studies confirm that children in host families shown better levels of subjective well-being than those in residential care (Llosada-Gistau, 2019; Llosada-Gistau et al., 2014).

In Spain, the host family program (?) measure was introduced in 1987 on Law 21/1987 of November 11st 1987. In Portugal, the first legislative proposal regulating this mechanism appeared in 2008, namely on Decree-Law 11/2008, as mentioned above. The new decree develops what is contemplated in the Law for the Protection of Children and Adolescents at Risk, Law No. 142/2015, of September 8th, specifically article 46 refers to family care as "attributing the trust of the child or young person to a natural person or relative, qualified for the purpose, providing them with their integration into

the family environment and providing care appropriate to their needs and well-being and the education necessary for their integral development". The legislative change continues to limit foster care to the external family without considering the possibility of extended families become foster family, but is a most common modality in the Spanish system.

Recent legislation recognises the right to receive financial support from the state for the maintenance of children in family . A system for the promotion of host families in society is established, with the purpose of attracting new families and expanding the application of the measure.

These legislative proposals seek to address awaiting issues in Portugal, as the implementation of family recruitment campaigns to promote the measure has historically been delayed, as well as the delivery of funds to cover the costs of host family programmes (Delgado, Carbalho, Montserrat e Llosada-Gistau, 2019). The results analysed in this article show that Portugal needs to promote this host family programs (?). The Portuguese protection system has an additional challenge to bring it up to the levels of the Spanish system, as the extended family remains outside the framework presented.

The prevalence of residential care is not determined by the fact that it is the measure most highly valued by the professional teams. Previous research concludes that the residential option is frequently chosen, even if it is not the most appropriate for the situation (Delgado et al., 2013), because it is the only one available.

Systemic precarity also affects work with biological families. The legislative proposals of both states, both Law 26/2015 on the reform of the child and adolescent protection system in Spain and Law 142/2015 of September 8th, recognise the importance of working with birth families. The data presented in this article show how the biological family continues to be a preferential option in the exit from the system's resources. International research has shown insufficiencies in the family support available to young people with administrative protection measures (Krinsky, 2010). Recent research carried out in the Portuguese and Spanish systems by Mateos, Fuentes-Peláez, Crescencia & Mundet (2018), show that professionals in both systems are aware of the importance of working with the families of social protected young people, carried out from a positive perspective towards achieving family reunification. However, other studies have shown the presence of insufficiencies in family intervention processes from protection resources in Spain (Melendro, De Juanas and Rodriguez, 2018) and Portugal (Távares-Rodrigues et al. 2019), professional action conditioned by the insufficient human resources, which affects the lack of time to work on these factors of interest (Fernández-Simo and Cid, 2017).

Insufficient resources in the socio-educational work with the young people leaving the system and the fragilities (?) in the intervention with the families, influence the permanence in residential resources. A comparative study on both countries, Spain and Portugal, about the protection systems, carried out by Távares-Rodrigues et al. (2019), concludes that the length of stay in residential centres is longer in Portugal, with an average of 5 years. The above mentioned aspects that determine the importance of working on the empowerment protection processes of adolescents. Personal emancipation is the main indicator of the quality of the system. Autonomy is the factor that will make it possible to overcome the situation of social difficulty that will conditioned the entire life itinerary of these young people.

The analysis carried out in this study shows that the results obtained by specialised emancipation resources are more positive than those of other types of residential resources. Particularly noteworthy are the young people who manage to leave the system to housing rented by themselves. The indicators for achieving this goal are favourable in both states. A comparison of the protection systems in Portugal and Galicia shows the scarcity of resources of this typology in the Portuguese system. There has been a slight increase in recent years in the number of young people accessing residential resources specialised in emancipation, but the number is still insufficient.

The information highlights the desirability of making progress in the implementation of resources for the preparation of independent living. Portuguese legislation in 2015 recognises the possibility of extending the system's support up to the age of 25. In the same year, Spain amended Law 1/1996, recognising the importance of starting intervention aimed at the process of transition to adulthood at the age of 16 and extending it until the necessary time. Preparation for autonomous life is a priority in a 21st century protection system.

Recent research has shown that resources for transition to adulthood are considered essential by young people with a protection record (Pérez-García et al, 2019; Fernández-Simo and Cid, 2018: Sala-Roca, Arnau, Courtney, & Dworsky, 2016), an understandable issue considering that youth in care have a high risk of perpetuating a situation of social vulnerability during their life journey (Mersky & Janczewski, 2013; Stewart, Kum, Barth, & Duncan, 2014; Greeson, 2013). Support resources during emancipation in the protection system facilitate overcoming the difficult challenges of independent living in contexts of vulnerability, working on the necessary aspects in each case (Yates & Grey, 2012). From a holistic perspective, the commitment to working on autonomy should not be to the detriment of other needs of the system, highlighting the importance of working with biological families as well as with referral programmes that enrich the social support networks available to adolescents. It is important to keep in mind that the effectiveness of accompaniment during the emancipation of young people transitioning from protective resources to independent living is conditioned by the stability of the referents (Casarrino-Pérez et al, 2018).

The future of sheltered youth will be conditioned by their level of qualification. Needs(¿)in social support determine the need to have their own resources to overcome their situation of social vulnerability. It is clear that a good level of education will facilitate the employment pathway. The information analysed highlights the alarming situation of this group in terms of their evolution at school. The data place young people under protective measures in a clearly unequal position compared to their peers. The situation in both states confirms the findings of Jackson and Cameron (2014), confirming that the school inclusion of this group is still pending in the forecasts of institutional policies.

Previous studies, carried out in the Iberian Peninsula (Távares-Rodrigues et al., 2019), found that in the Portuguese case there was an average repetition rate of 2.75 years of schooling. In Spain, 70% had repeated at least one school year. In both countries, 40% of pupils were in a lower grade than their chronological age. Other research shows that the low qualification obtained during the permanence in the protection system leads to a risk of social exclusion during adulthood (Fernández-Simo and Cid, 2014; Casas and Montserrat, 2009; Okpych and Courtney, 2014; Jackson and Martin, 1998). School integration is a protective factor during the process of transition to adult life (Gradaille, Montserrat & Ballester, 2018), with consequences throughout the life itinerary, in key issues for overcoming the situation of social difficulty, such as low life expectations (Montserrat, Casas & Sisteró, 2015). The above situation highlights the importance of the Spanish and Portuguese governments adopting specific measures for the school integration of adolescents in protection. The proposals require a comprehensive perspective from a mesosystem perspective, coinciding with previous proposals by authors such as (Montserrat et al, 2011), who highlight the importance of coordinated action between protection resources and schools.

The results point to important challenges for improvement in the child and adolescent care systems of both states. Hopefully, recent legislative reforms will facilitate the necessary changes in child protection practices in Portugal, as previously noted by other research (Rodrigues et al. 2013). The information analysed highlights the desirability for the Portuguese state to organise a remodelling of the protection system, overcoming old reluctance to change, which according to Delgado (2015) is present in certain organisations.

Conclusion

The Portuguese and Spanish protection systems share a similar reality of action. These socio-cultural similarities are especially present in the comparison of the Portuguese and Galician systems. The study analyses the bureaucratic constructions organised by the corresponding governments to respond to the most vulnerable children and adolescents. The differences between the two systemic structures are relevant. The results of protective action reveal notable needs (¿)in both systems. Intervention with families, the emancipation process and school integration are aspects of relevance in the quality of protective action. All indicators point to significant room for improvement. The situation is particularly worrying in the case of Portugal.

Awareness of the areas for improvement that need to be developed is the first step towards the implementation of effective protection policies. This paper provides a comparative perspective of the situation in both states, based on official data and previous research. We highlight the convenience of carrying out qualitative studies that allow us to analyse on the ground the concrete reality that statistical indicators provide us with. It would be positive to continue with comparative work on the perspective that the actors involved have of protective action. In any case, the challenges of both systems are important, with the intention of helping adolescents under protection to overcome their situation of social exclusion.