Introduction

Newborns, in particular those who need to be admitted in neonatal intensive care units, undergo several procedures that cause pain, mostly procedures related with punction - venous, heel or lumbar punction.

Preventing acute pain in newborns by providing a combination of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapy is the best way to prevent short and long-term consequences of adverse neurodevelopmental effects, especially in pre-term infants (Anand, 2019).

The Eutectic Mixture of Local Anesthetics (EMLA) is a mixture in equal parts of Prilocaine and Lidocaine and is known as an effective way to reduce pain during procedures. However, there are doubts about safe dosage in newborns, especially because of the risk of increasing Methemoglobinemia - identified in the 1990s (Frey & Kehrer, 1999; Dutta, 1999) - but that further studies demonstrated to be residual (ANMPS, 2016; EMA, s.d.).

The objective of this review is to identify how EMLA cream is used to reduce pain, without adverse reaction, in newborn infants undergoing painful medical procedures. Those procedures can be performed at a hospital, at primary care or even at home.

This aim is expressed in the research question “Which Eutectic Mixture of Local Anesthetics cream dosage is used in newborns undergoing painful procedures?”

A preliminary search for previous scoping reviews and systematic reviews - or their protocols registration - was made at Pubmed, Prospero and OSF, with no results. This scoping review protocol is registered at OSF with doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/YKD85.

Review Question and inclusion criteria

The research question “Which Eutectic Mixture of Local Anesthetics cream dosage is used in newborns undergoing painful procedures?” was defined with PCC methodology, where:

Population: Healthy newborn infants up to 28 days old (considered preterm if born before 37 weeks gestational age, or full-term if born after 37 weeks gestational age).

Concept: To understand which dosage of EMLA cream is needed to reduce pain related to medical procedures in newborns. This will be assessed by two described outcomes: (1) reducing pain during procedure - pain assessment with a validated scale/procedure - and (2) the dosage of EMLA cream used: amount, time of skin contact, and if an occlusive dressing was used.

Context: Painful procedures during medical care can occur at different settings like hospital, primary care or even at home if the medical care is provided there.

1. Methods

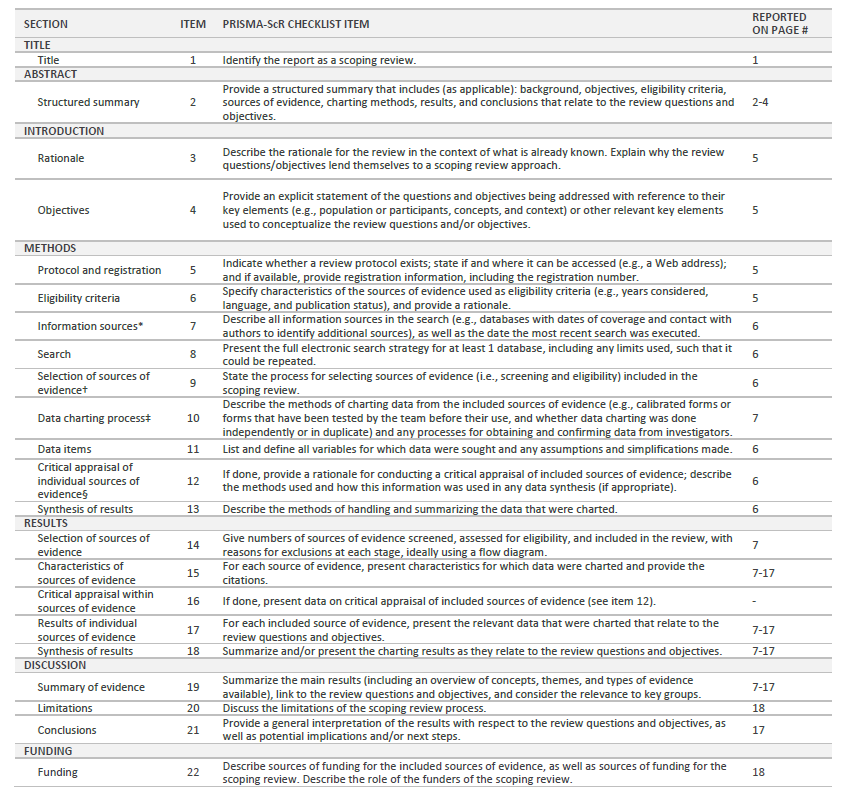

The present scoping review is guided by JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Peters et al., 2020), and PRISMA ScR Extension Fillable Checklist (Tricco et al, 2018) is used to report guidance.

1.1. Search Strategy

In order to search for relevant literature, we used PubMed, CINAHL, MEDLINE and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews via EBSCO, as well as RCAAP (Repositórios Científicos de Acesso Aberto de Portugal), DGS’site (Direção Geral de Saúde) and SPN’ site (Sociedade Portuguesa de Neonatologia) to review relevant gray literature in Portugal.

MeSh search terms were identified and the search phrase ((((Pain[MeSH Terms]) OR (acute pain[MeSH Terms])) OR (Pain, procedural[MeSH Terms])) AND (((Lidocaine, Prilocaine Drug Combination[MeSH Terms]) OR (Eutectic Mixture of Local Anesthetics[MeSH Terms])) OR (EMLA Cream[MeSH Terms]))) AND (Newborn[MeSH Terms]) was created. Filters “full-text”, and “timeline 2002 - 2021” were applied, in order to find the most recent evidence with full access to the document. The filter “Apply equivalent subjects” at EBSCO was unselected. There was no idiom restriction. For gray literature search, the terms used in Portuguese were “EMLA”, “dor” and “recém-nascido”, with the same full-text and timeline filters at RCAAP, not applied on the other websites. The search was made in February 2022.

The inclusion criteria were: newborn population up to 28 days old (both pre-term and full-term); the EMLA cream’s protocol should describe the amount of cream and time of skin contact; and EMLA cream must have shown effectiveness in pain reduction.

After retrieving the documents, evidence selection was made by deduplication, title analysis, abstract analysis, and full-text analysis.

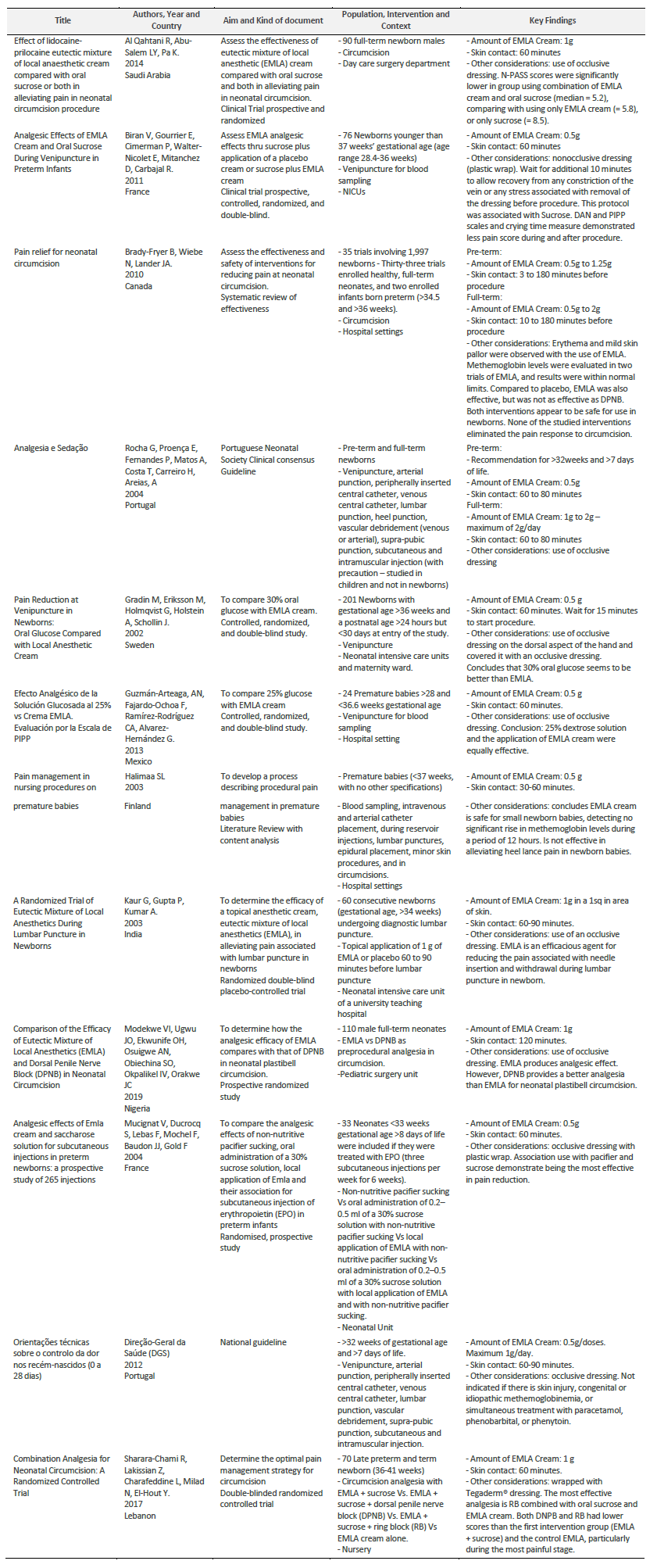

There were identified 12 documents: 8 trials, 2 reviews and 2 guidelines, describing a population of 2.661 newborns from 28 weeks of gestational age until full-term.

Result’s synthesis is presented in a table where key findings as amount of EMLA Cream and skin contact time are described, as well as other relevant considerations.

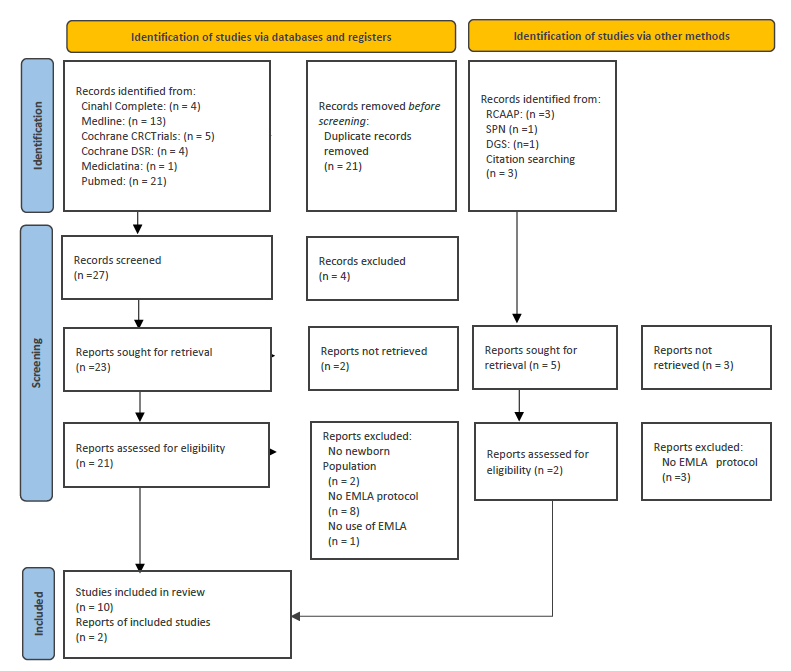

The PRISMA diagram (Page et al., 2021) (Figure1) shows how selection has progressed.

2. Results and discussion

The analysis of the 12 selected documents pointed to the following results.

2.1. EMLA cream’s efficacy

The studies that compared EMLA cream with placebo demonstrated that EMLA is effective in pain reduction in newborns (Biran et al., 2011; Kaur et. al, 2003).

Studies comparing EMLA cream with oral sweet solutions are more controverse: one study shows that EMLA cream was more effective than sucrose (24% glucose oral solution) and that the combination of both EMLA cream and sucrose was even more effective (Al Qahtani et. al, 2014); another study concludes that 30% glucose was more effective than EMLA cream (Gradin et. al, 2002); and another study concludes that 25% glucose was as effective as EMLA cream (Guzmán-Arteaga et. al, 2013). The study that compares EMLA cream with pacifier and sucrose use, and with pacifier and sucrose association (Mucignat et al., 2004), concludes that the most effective was the combination between EMLA cream, pacifier sucking and sucrose administration.

Analyzing the results, we verified that EMLA cream is not effective at heel lancepain (Halimaa, 2003), but has shown efficacy at circumcision (Al Qahtani et. al, 2014; Brady-Fryer et. al, 2004; Modekwe et. al, 2019; Sharara-Chami et al., 2017), venipuncture (Biran et. al, 2011; Gradin et. al, 2002; Guzmán-Arteaga et. al, 2013; Halimaa, 2003), lumbar puncture (Kaur et. al, 2003), and subcutaneous injections (Mucignat et al., 2004).

At circumcision analgesia studies, EMLA cream alone is not as effective as Dorsal Penile Nerve Block (DPNB) (Modekwe et. al, 2019), but if used in association with sucrose and Ring Block (RB) it has demonstrated more efficacy than DPNB (Sharara-Chami et al., 2017).

2.2. EMLA cream’s dosage

Two protocols didn’t distinguish EMLA cream’s dosage between pre-term and full-term newborns (Kaur et. al, 2003; DGS, 2012). Portuguese national guideline doesn’t recommend the usage of EMLA before 32weeks of gestational age, recommending a 0.5g/dose of cream (DGS, 2012). The other study’s population were late-premature (>34 weeks) and full-term newborns, with a recommendation of 1g/dose (Kaur et. al, 2003).

Pre-term Newborn

In the selected articles, preterm gestational age ranges from 28 (Guzmán-Arteaga et. al, 2013) to 37 (Halimaa, 2003) weeks.

The EMLA cream’s protocol concerning pre-term newborns (Biran et. al, 2011; Brady-Fryer et. al, 2004; Rocha, 2004; Guzmán-Arteaga et. al, 2013; Halimaa, 2003; Mucignat et al., 2004; DGS, 2012) recommends the use of 0,5g of EMLA cream, although a systematic review identifies a 1,25g dosage for circumcision (Brady-Fryer et. al, 2004).

The systematic review included in this scoping identified a range between 3 and 180 minutes of EMLA cream skin contact. 60 minutes seems to be the most consensual skin contact time (Biran et. al, 2011; Guzmán-Arteaga et. al, 2013; Mucignat et al., 2004). However, one protocol considered that it might be effective from 30 minutes (Halimaa, 2003) and the two guidelines’ protocols considered more time - 80 minutes (Rocha, 2004) and 90 minutes (DGS, 2012).

Full-term newborn

For full-term newborns, 1g of EMLA cream is the most frequent amount used (Al Qahtani et. al, 2014; Kaur et. al, 2003; Modekwe et. al, 2019; Mucignat et al., 2004). However, one protocol considered less quantitity (Gradin et. al, 2002), while a previous systematic review considered a range from 0,5 to 2g (Brady-Fryer et. al, 2004), and the Portuguese Neonatology Society considers a range from 1 to 2g (Rocha, 2004). One study specifies the distribution of 1g in 1 square inch (Kaur et. al, 2003), and the Portuguese national guidelines (DGS) recommend a maximum of 1g per day (DGS., 2012).

60 minutes is also the most consensual period of skin contact time for full-term newborns (Al Qahtani et. al, 2014; Gradin et. al, 2002; DGS, 2012), although one study used a 120-minute skin contact protocol (Modekwe et. al, 2019), and two other protocols considered a range from 60 to 80 minutes (Rocha, 2004) or to 90 minutes (Kaur et. al, 2003). A review identified a range from 10 to 180 minutes when the procedure is the newborn’s circumcision (Brady-Fryer et. al, 2004).

2.3. Occlusive dressing use

Most of the retrieved protocols referred the use of an occlusive dressing during the EMLA cream’s skin contact (Biran et. al, 2011; Rocha, 2004; Gradin et. al, 2002; Guzmán-Arteaga et. al, 2013; Kaur et. al, 2003; Modekwe et. al, 2019; Mucignat et al., 2004; DGS, 2012). Most of them do not identify how that dressing is done, although two of them identified the use of plastic wrap (Biran et. al, 2011; Mucignat et al., 2004), and another one identified the use of Tegaderm® dressing (Sharara-Chami et al., 2017). One study considered the dressing removal as a moment that can induce stress or pain, so an additional 10-minute time was given (Biran et. al, 2011).

2.4. EMLA’s adverse reactions

Some reactions were identified on the considered studies, such as erythema and mild skin pallor (Brady-Fryer et. al, 2004). Methemoglobin levels were evaluated in one study during a period of 12 hours, with no significant rise (Halimaa, 2003).

Data results are summarized in Table1. It expresses EMLA cream’s protocol, detailing: the amount of cream; time of skin contact; the use of an occlusive dressing and EMLA cream’s effect reducing pain.

Conclusion

EMLA cream has shown efficacy to reduce pain in newborns undergoing painful procedures, especially on procedures where needles are used.

There is no consensus on which EMLA dosage is safe to use in newborns.

In pre-term newborns, 0,5g is the most frequent amount and 60 minutes is the most common time of skin contact, with ranges that can vary from 0,5 to 1,25g in the amount, and from 3 to 180 minutes in skin contact time.

Considering full-term newborns, 1g is the most frequent amount and 60 minutes is the most frequent skin contact time, with ranges that can vary from 0,5g up to 2g in the amount, and from 10 until 180 minutes in skin contact time.

Although most reviewed protocols have included the use of an occlusive dressing during the EMLA cream usage, there is no evidence of advantage in this procedure.

Implications of the findings for research

EMLA cream’s efficacy in newborns has been described for decades, although there is still a lack of consensus in protocols and guidelines. This scoping systematizes information in order to helpfully encourage further studies on this matter, especially in pre-term newborns.