Introduction

Medication use has been increasing due to the need to treat chronic, age-related diseases and the clinical advances in care (Khezrian et al., 2020). Medications are and will continue to be a cornerstone of healthcare quality.

The concept of pharmaceutical care (PC) corresponds to the responsible provision of medications to achieve definite outcomes that improve patients’ quality of life (Hepler & Strand, 1990). Dilles et al. (2010) add that PC also includes medication management (ordering, storage, preparation, administration, evaluation of effects and patient orientation).

Nurses, physicians, and pharmacists play different roles in PC (Choo, Hutchinson, & Bucknall, 2010). Historically, nurses have been responsible for medication preparation and administration. However, in recent decades, their responsibilities have expanded due to the transfer of medical responsibilities (Maier & Aiken, 2016).

In several settings, nurses take on responsibilities in PC that go beyond medication preparation and administration. Their roles in interprofessional teams have been little explored, which perpetuates the blurred boundaries in PC interventions and responsibilities between nurses, physicians, and pharmacists. This unclear definition of roles, together with the differences across European countries, has had a negative impact on the quality of care, nurse training, and job mobility (Maier & Aiken, 2016; Wilson et al., 2016).

A quantitative, cross-sectional survey was conducted in 17 European countries to clarify these roles. Nurses, physicians, and pharmacists gave their opinions about nurses' practice in interprofessional PC, their tasks, and the collaboration/communication between the professionals involved (De Baetselier et al., 2020). The following responsibilities of nurses in PC emerged: patient education and information about medication, management of medication adherence, surveillance and recording of beneficial and adverse events, medication prescription, and intervention in case of adverse effects. This study resulted in a preliminary model for the project: “Development of a model for nurses' role in interprofessional pharmaceutical care” - DeMoPhaC (De Baetselier et al., 2021), which aimed to develop a model for nurses' intervention in Europe. This article describes the contribution of Portuguese physicians to the development of this model for nurses’ role, thus clarifying their roles (responsibilities and interventions) in interprofessional PC.

1. Methods

A qualitative, descriptive, and exploratory study (Polit & Beck, 2019) was conducted to identify Portuguese physicians’ opinions about nurses’ roles (responsibilities and interventions) in interprofessional PC, the strengths and weaknesses in nurses’ roles, and the potential threats and opportunities for quality of care.

This study met the ethical and deontological requirements in its various stages (informed consent, confidentiality, data accessibility and self-determination). It received a favorable opinion from the Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing of the Nursing School of Coimbra (Opinion No. 543/12-2018).

Participants

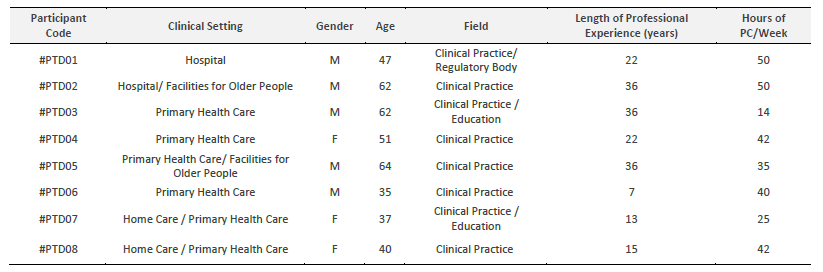

Eight physicians were selected intentionally (Polit & Beck, 2019) for their recognized expertise in PC. The availability and interest shown in participation were relevant requirements for selection. The minimum requirements for inclusion were as follows: clinical experience greater than or equal to 5 years; being part of an interprofessional team; and working in hospital care, primary health care, home care, or facilities for older people.

The selection followed the snowball sampling method (Vinuto, 2014), in which the first participant was selected at the researchers’ workplace.

Each participant was assigned a code to ensure data confidentiality. Example: #PTD01 - #PT (Participant's country - Portugal); D (Profession - Physician); 01 (Order number).

The participants’ mean age was 49.8 years, ranging from a minimum of 35 to a maximum of 62 years. Five were men, and three were women. The length of professional experience ranged from 7 to 36 years, with a mean of 23.4 years. On average, the time spent on clinical practice directly related to PC was 37.3 hours/week, ranging from 14 to 50 hours/week.

Data collection

Data were collected between February and June 2019 at the participants’ workplaces and outside their working hours through semi-structured interviews.

The interview script consisted of four guiding questions: What responsibilities would be part of the nurses’ ideal role in PC, and what do they entail?; What specific tasks should nurses perform in PC?; How do you perceive collaboration and communication between nurses and other health professionals in PC?; What are the strengths and weaknesses of the nurses’ role in PC, and what are the opportunities and threats to this role?

Each participant was first contacted by phone. Participants were provided information by email prior to the interview and explained the study’s context and objectives. None of the participants contacted declined to participate in the study.

The interviews were guided by a script built by the DeMoPhaC researchers and later adapted to the Portuguese social, cultural, and healthcare context by a group of seven Portuguese researchers.

Two pilot interviews were conducted to train the researchers and test the interview script, thus ensuring quality in data collection.

Prior to each interview, participants were asked permission to record a social conversation (without the presence of third parties) to promote closer interaction between interviewer and interviewee. The participants spoke freely and without constraints of any kind during the interviews. The interviews lasted an average of 36 minutes, ranging from 23 to 49 minutes.

Interviews were transcribed at the same time they were applied to extract the main contents and assess further ways to explore some aspects. Verbatim transcription included both verbal and non-verbal communication (recorded in field notes).

Methodological rigor was followed in data collection and analysis. The participants validated the transcribed data (including field notes). Any doubts were clarified with feedback to participants to confirm their perceptions and experiences (credibility), obtain congruence about the accuracy and relevance of the data from the mentors and researchers (objectivity), and provide sufficient descriptive data to enhance its potential for application in other contexts (transferability).

Participants were reminded of their freedom to change the interview content if they so wished.

Content analysis

Data were analyzed using the editorial style described by Polit and Beck (2019), which starts by identifying relevant interview excerpts (record units).

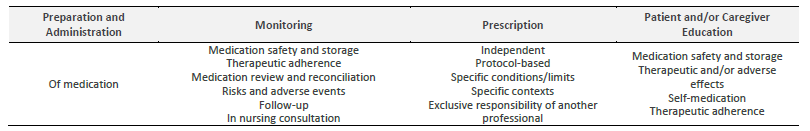

After reading and rereading the interview transcripts, two authors independently coded the relevant excerpts. The compilation of both analyses resulted in a coding table (with multiple codes, subcodes, and respective record units). Nine categories emerged (Preparation and Administration; Monitoring; Prescription; Patient and/or Caregiver Education; Requirements or Conditions for the nurses’ active role in PC; Strengths; Weaknesses; Opportunities; and Threats), as well as 36 subcategories. In the third and last coding step, integrative core categories were created that resulted in three core themes: “Nurses’ functional content in PC”; “Requirements for nurses’ intervention in PC”, and “Revision of nurses’ functional content in PC”.

The theme “Nurses’ functional content in PC” encompasses nurses’ responsibilities and tasks in PC from the participants’ perspectives. The theme “Requirements for nurses’ intervention in PC” includes categories corresponding to the criteria for nurses’ active participation in PC. The core category “Revision of nurses’ functional content in PC” includes the data from the analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of nurses in PC, as well as the opportunities and threats to nurses’ intervention in this area.

2. Results

Participants classified nurses’ tasks into four areas: preparation and administration; monitoring; prescription; and patient and/or caregiver education (Table 2).

“The nurse prepares the medication, (...) administers the medication, (...) evaluates the side effects, adverse effects that may exist later on” #PTD05.

“The follow-up of clinical evolution, (...) something they do every day. They often ring the alarms for the medical staff (...) they play a key role in teaching patients about self-medication and monitoring them” #PTD01.

“Informing the person, clarifying doubts about how to take the medication, (...) educating the person in nursing consultations” #PTD07.

The references to prescription-related activities were not unanimous. Prescribing by nurses is possible if there is specific training (for the nurses involved), definition of protocols, limitation to specific patient groups or medications, medical supervision, and changes in policies and/or mindsets.

“I believe they can play a role in active prescribing... they should. And that’s the way to go! (...) I don’t think it makes sense for everyone to allow everything! But, with proper training and specialization, they should expand their tasks, have a set of therapeutics they can use” #PTD06.

“(Protocol-based nursing prescription?) Yes. Totally. If there is a protocol and problems are identified. For example, a protocol for administration of antipyretics, (...) for insulin (...) I think that makes sense” #PTD05.

“I think that right now there are no conditions for nurses to take on that responsibility” #PTD08.

“There is a part of prescribing, (...) the most commonly used drugs, (...) as long as there is training, especially to identify the cases in which they should not be used” #PTD06.

“(...) emergency therapy, such as for pain, (...) for fever, (...) for trauma. I don’t disagree with that at all, as long as the contexts in which they are necessary or contraindicated are known (...)” #PTD03.

“I think nurses can decide on the administration of adrenaline or other drugs, for example, in advanced life support” #PTD01.

“But with a protocol (...) there must be a protocol” #PTD07.

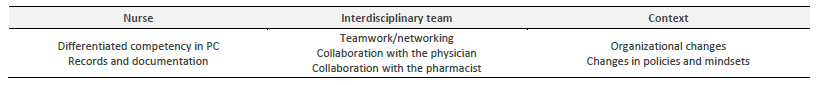

Physicians pointed out requirements or necessary conditions for nurses’ involvement in PC. The requirements are associated with the nurse, the interprofessional team, and the context (Table 3). Nurse-related requirements refer to differentiated competency in PC and records and documentation:

“(...) there would be basic training only for some nurses who would have to be always present on the ward, every shift, to be able to perform these therapeutic tasks” #PTD01.

“First, there should be a support to communication. Of course, things can be verbalized, but there should be written support. (...) A computer or paper record. A record of communication” #PTD05.

The requirements of the interdisciplinary team were related to teamwork/networking in collaboration with the physician and pharmacist:

“It does not mean that there cannot be mixed consultations ... I mean, it all has to do with each person’s training. I think it is an asset! (...) we already do that! I schedule the follow-up appointment with the nurse (...)” #PTD04.

“When it comes to nurses and doctors (...), there must be a very close dialogue. (...) This clinical assessment cannot be done separately; it must be shared. The medical team and the nursing team must share that clinical decision-making” #PTD01.

“(...) it should include reporting, alerting, and discussion among the professionals. That is essential” #PTD02.

“(...) that pharmacists themselves be part of an extended therapeutic team that meant that there was consistency (...) and we would create a triangulation here, or rather a quadrangulation, that could be more virtuous and much more efficient” #PTD03.

Contextual requirements were related to changes in the organizations, policies, and mindsets of the main stakeholders in society:

“A change in mindset, of course, there would be a lot to change in terms of mindset. Schools would have to change. Legally, the mentality of nurses, institutions, physicians, everything would have to change; it could take some time for them to adapt to this new system” #PTD01.

“(...) As long as the roles are well-defined, there will not be any difficulties. There can be problems if there are common aspects and if we do not know who is going to intervene. Therefore, this definition is fundamental.” #PTD05.

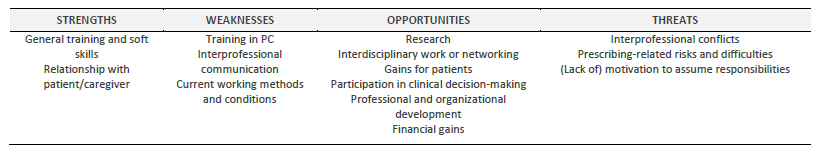

The authors analyzed the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats related to the development of an interprofessional model for nurses’ role in PC (listed in Table 4).

The physicians identified the following strengths: nurses’ general training, soft skills, and the nurse-patient/caregiver relationship:

“A robust training in health focused on health gains for people. In terms of communication and so (...) This collaboration with the caregiver, with the family, to understand if more precautions and more attitudes could be taken (...)” #PTD07.

“They establish a good relationship of trust between the nurse and the patient (...) Through a good relationship of trust with the patient, we obtain important information and manage to provide quality care” #PTD08.

The following nurses’ weaknesses were identified: specific training or preparation in PC, interprofessional communication, and current working methods and conditions:

“Neither the training nor the practice was directed towards it... yet... maybe this will blur in a few years. At first, the biggest problem is the training deficit! They were formatted for one type of training and now ... cover other skills?” #PTD06.

“(Interprofessional communication) First, one must process, and that sometimes does not happen” #PTD07.

“(...) the system does not motivate people, it also has to do, for example, with the views of those who organize this training (on pharmacotherapy) who do not recognize that it makes sense for them (nurses) to be included” #PTD07.

“Lack of some conditions too, (...) of time, lack of training rooms” #PTD04.

The participants mentioned the following potential opportunities: research (only by nurses or interprofessional), interdisciplinary work or networking, participation in clinical decision-making, gains for patients, and possible financial gains:

“Multidisciplinary research. There is little, but it can be an opportunity” #PTD07.

“I am a fan of teamwork. And it is always good for the team to work well. So, this is an opportunity for nurses to acquire more skills and more responsibilities... it improves the team or the outcome of teamwork” #PTD02.

“(...) the creation of these networks, ... of forms of contact” #PTD03.

“(If there is greater responsibility of the nurse) Then, the reaction is more immediate than having to wait for a doctor. (...) Not to mention that, in certain periods, (...) the medical support decreases and is less close to the patient. Therefore, the patient only stands to gain from it” PTD01.

“A force to reduce therapeutic costs. Not only at the therapy level but also concerning staff costs” #PTD03.

“With the current financial constraints, the physician is a more expensive team member and weighs more heavily on public finances than the nurse. Besides, the nurse already has a direct relationship with the patient and can take advantage of it to write that prescription, do that follow-up” #PTD01.

On the other hand, they identified the following potential threats to nurses’ role in PC: interprofessional conflicts, prescription-related risks and difficulties, and the possible demotivation of nurses to assume a differentiated role in PC:

“The definition of boundaries will remain a difficult problem... Because each person will always want to call upon themselves the possession or ownership of a certain act” #PTD02.

“If we change this scenario, we will put the nurse on a more equal decision-making level with the physician. That could trigger a conflict, could it not? (...) Problems that will certainly arise when assuming the role of prescriber...” #PTD01.

“We have more and more polymedicated patients, more and more side effects, and... we really have to be very careful” #PTD04.

“(...) the motivation of the nurses themselves, who often do not think it is that important to update their knowledge (on medication management)” #PTD07.

3. Discussion

In recent decades, we have witnessed nursing affirming itself in Portugal as a core profession in health care, as well as significant advances worldwide in the profession’s competencies and functional content, particularly regarding PC.

Nurses’ functional content in PC is consistent with the views of the participants in this study. Leufer and Cleary-Holdforth (2013) state that nurses should not forget their importance in medication preparation and administration, as it represents one of the last safety checks and the final opportunity to ensure validity and patient safety in medication administration.

Johansson-Pajala et al. (2016) refer to nurses as vigilant intermediaries, acting as a link between all members of the interprofessional team, including the patient. Nurses continuously monitor and ensure the safe administration of medications, monitor their effectiveness, and intervene rapidly in case of need.

Adherence to any treatment plan depends on several variables, including the willingness of the patient/caregiver to manage their disease effectively (Virgolesi et al., 2017). This can only be achieved if the patient and/or caregiver education is carried out by the team member who is closest and most confidant of the patient/caregiver.

Some participants believe that prescribing as a nursing task can still be a reality in the future. In specific conditions and contexts, it may be a path to be followed to obviate and speed up the efficiency of the health system and increase the health-related quality of life of patients/caregivers. However, it should be noted that Portugal is a relatively small country with remarkable technological development but without solid training of nurses in PC that allows for the design of protocols, the definition of target patient groups, and the development of a relationship of trust that will only be effective when there are political and/or mentality changes in society.

In most countries, jurisdiction over prescribing remains predominantly with the medical profession. In countries focused on the efficiency of the healthcare system, there are broader prescribing rights (Maddox et al., 2016). The lack of physicians, the increase in chronic diseases, interprofessional collaborative work, and the increase in nursing education are other catalysts for this change.

The scope of prescribing rights varies considerably, with only three European countries (Ireland, Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) granting certain groups of nurses (“nurse prescribers”, “nurse specialists”, and “independent nurse prescribers”) prescribing competencies within their specialty. In other countries, there are restrictions in the medication record and the range of authorized medications is defined after an initial prescription by a physician. All these countries have regulated the conditions under which nurses can prescribe; most require additional records concerning the prescription and some physician supervision to ensure patient safety (Maier, 2019).

In the last two decades, Spain has been moving towards medication prescribing by nurses. However, the first protocol for clinical nursing prescribing in wound care was only created in October 2020. Romero-Collado et al. (2014) pointed out that the legalization of prescribing increases professional autonomy and contributes to the development of the profession.

The requirements associated with nurses’ intervention in PC relate to the need for a differentiated competency in this care and improvements in recording and documentation. This aspect is highlighted by Heczková and Bulava (2018) when they conclude that knowledge associated with the quality of training is one of the many factors that have an impact on reducing the risk of adverse events and providing safe care, indicating the need for attention, focus, and methodology in nursing education in PC.

These improvements in recording and documentation align with Silvestre et al. (2017) when they characterized documentation of all medication-related healthcare practices (both direct and indirect) as fundamental to improving safety in PC. The implementation of electronic prescribing systems also emerged as a potential factor in reducing the risk of medication errors (Volpe et al., 2016).

Other requirements focused on the interprofessional team, in which collaboration is seen as essential for providing safe and patient-centered care. The contribution of all health professionals, the relationships established between them, and the environment in which PC is provided are key factors for medication safety (Choo, Hutchinson, & Bucknall, 2010). Changing the organizations’ safety culture related to error reporting and effective communication between professionals leads to gains in safety and quality of care (Ghahramanian et al., 2017).

The participants also mentioned the need for contextual changes for nurses’ active participation in PC because these developments in nurses' skills are like a disruptive health innovation, with implications for nurses and their teams, and are influenced by policies and regulatory mechanisms (Maier, 2019).

Participants identified the need for a clear definition of roles for all elements involved. This aspect is advocated by authors such as Celio et al. (2018), who suggest that regulatory and policy organizations should clearly define the roles of the health professionals involved.

In parallel with the regulations, the professionals’ education/training should also be taken into account, and support should be provided to develop the competencies of these non-medical prescribers (Maddox et al., 2016).

According to the participants, the clarification of the roles (responsibilities and interventions) of nurses in PC within interprofessional teams should be based on their solid training, particularly their non-instrumental component (soft skills) and the relationship established with patients and caregivers, which were also highlighted by Ng (2020).

As weaknesses, participants identified interprofessional communication, current working methods and conditions, and gaps in preparing students and nurses for interprofessional collaborative work. The latter aspect has already been identified in previous studies (Latimer et al., 2017).

To enhance knowledge in sensitive areas with shared responsibilities such as PC, Wilson et al. (2016) advocate shared education as preparation for interprofessional work in this and other areas. Interprofessional cooperation based on communication allows for information sharing, enhanced decisions, and optimized care.

According to the participants, the opportunities for the development of an interprofessional PC model with a clear definition of nurses’ roles include the possibility of greater participation in research, interprofessional work in multiple care settings, gains in the quality of care for patients, participation in clinical decision-making (not only in meetings, but also in protocol definition or joint training), professional and organizational development in this particular area, and financial gains for the health system.

In this regard, the prescribing model in the United Kingdom has increased patient satisfaction and improved the system’s financial outcomes. There is robust evidence that this model for medication prescribing, in which physicians and non-physician health professionals coexist, promotes financial returns in a situation of increasing healthcare demands and restricted funding (Noblet et al., 2019). Clinical practice regulations that allow nurses to prescribe without physician supervision are associated with improved medication adherence (Muench et al., 2021).

Possible interprofessional conflicts (particularly if there is an expansion of nurses’ responsibilities in PC), prescribing-related difficulties and risks (due to the complexity associated with situations of multiple comorbidities and constant pharmacological evolution), and a possible lack of nurses’ motivation to assume new roles are pointed out as threats to nurses’ participation in PC.

4. Limitations

The results of this study should be considered ecological within the specific context where it was developed. Its limitations include the sample size (eight participants) and the perspective of only one member of the interprofessional PC team. It should be noted that although eight physicians were interviewed, data saturation was reached in the last interviews.

The snowball sampling method facilitated the identification of potential respondents but may have resulted in a more homogeneous sample, hence the potential data saturation.

Finally, software was not used for data content analysis, which may add subjectivity to interpretation. Although it is admissible in this type of study, it may influence the clarity of some points of view. However, manual data processing for eight interviews is much more practical and even reliable for this type of study.

Conclusion

The interviewed physicians revealed that nurses should maintain their active participation in interdisciplinary PC in Portugal. Nurses are considered guarantors of safety in medication care, as reflected in their responsibilities and interventions during preparation, administration, monitoring, prescription, and education. The degree of autonomy and relevance of these interventions is clear, except for prescribing, where opinions differ. A wide range of concepts has been identified, ranging from the possibility of independent prescription with some conditions to exclusive prescription by the physician.

Some requirements related to the nurse, the interdisciplinary team, and the intervention or political context should be met for nurses to perform the tasks in PC.

The strengths of the clarification of nurses’ roles (responsibilities and interventions) in the interprofessional PC team are nurses’ active role in PC, general training, soft skills, and the empathic and close relationship established between nurses and patients/families. As weaknesses, they identified the specific training of nurses in PC to start prescribing, the interprofessional communication, and the current working methods and conditions in Portuguese healthcare institutions. There are many opportunities, including research in this area, interdisciplinary work, patient gains, professional and organizational development, and possible financial gains for the system and society. However, threats were also identified, such as interprofessional conflicts due to the increase in nurses’ responsibilities, prescribing-related difficulties and risks, and the low motivation of nurses to assume new tasks.

This research can serve as a starting point for reflecting on nursing curricula due to the need to enhance training in PC within interprofessional teams. Future studies on the expansion of nurses’ skills in PC should serve as the basis for this training.