Introduction

In 2019, the world was ravaged by the Coronavirus Pandemic. The Coronavirus (SARS COV2) is the cause of COVID-19, an infectious disease that mainly attacks the airways and can lead to death in infected people. The elderly were the main victims of the disease and, according to data widely publicized in the media and confirmed by the Pan American Health Organization, 76% of deaths related to COVID-19 between February and September 2020 were of people over 60 years old (PAHO, 2020), with a reduction in the average life span of 1.9 years for the Brazilian elderly (Camarano, 2021).

The impact of the high mortality of the elderly during the Pandemic, in addition to the emotional and affective impacts, was also reflected in family income. Studies show that elderly workers, retired or pensioners have provided, in many families, minimum housing and food conditions for their own unemployed or underemployed children and/or grandchildren (Camarano, 2020).

According to Camarano (2020), income from work, retirement and pensions has supported families and greatly helped in the movement of local commerce in small towns. Elderly people have made a relevant contribution to family income, taking the role, in many cases, of main providers. " It was observed that in 60.8% of households with elderly people or in 20.6% of all Brazilian households, the income of the elderly was responsible for more than 50% of their income” (p. 4171).

In this way, the Pandemic impacted not only family relationships, but also the living conditions of many young people and children who depend on the income of the elderly. In addition, it made the deep economic, racial, and educational inequalities in Brazil more evident, affecting mainly the poorest, black people and residents of the periphery, with fewer resources for basic sanitation and conditions to maintain the social isolation recommended by health authorities (Kalache et al. al, 2020).

When the first scientific studies on the disease were released, in March 2020, social isolation measures were imposed, and the elderly became the target of care politics. Visits to inmates in long-stay institutions (ILPI) were prohibited, and family nuclei were prevented or advised against meeting with relatives living in other residences. Consequently, family get-togethers and visits to grandparents dropped dramatically.

Faced with a difficult social and economic reality, in which social distancing and the fear of contracting and/or transmitting the virus to close people was very present, children and the elderly were two generations that have particularly suffered during the Pandemic. Whether due to physical distancing, fear of death of the elderly, victims of COVID 19 or other evils, families have been looking for other ways to interact and put children in contact with uncles, grandparents, and other members of the family group.

Research has shown that social isolation caused intense feelings of fear, anxiety, and lack of affective contacts, among other negative feelings, often resulting in depression in the elderly (Viana, Silva & Lima, 2020). On the other hand, positive feelings between grandparents and grandchildren are built in exchanges and are strengthened in the practical exercise of affection, positively affecting the well-being of grandparents, parents, and grandchildren.

Although young people born in the 1990s onwards have lived with information and communication technologies (ICTs) from an early age, today we can say that virtual sociability is not restricted to the youngest. Different age groups have found in social networks an efficient and fast way of communication and interaction, both regarding commercial and corporate relationships, as well as the acquisition of new friendships and participation in groups of family and friends. A survey carried out by Casadei, Bennemann & Lucena (2019, p. 2) showed that, in 2016, approximately 50% of Brazilian elderly people used virtual social networks, with Facebook and Whatsapp being the most accessed, a percentage that increased during Pandemic.

Still far from everyone's reach, cell phones that allow access to the internet (smartphones) are the most used by the elderly to interact virtually. Such devices allow access to games, different banking operations, social networks, taking pictures and sending written and voice instant messages. Without requiring basic computer skills for their operation, as is the case with computers and tablets, smartphones allow mobility and easy access. It is within reach anywhere and has multiple uses. The authors mentioned above also demonstrate in their study that, despite the natural difficulties in handling technological devices, accessing the internet and communicating through virtual means, interaction through social networks brings benefits to the elderly, ranging from social interaction to acquisition of health and wellness information:

Therefore, it is problematized that certain negative psychosocial aspects, common to the elderly, such as loneliness, social isolation, and alienation, can be minimized with the appropriate use of virtual social networks (RSV) on the Internet, enabling the maintenance and/or deepening of family / social relationships, improving cognitive levels, in addition to being a useful tool in obtaining health information (Casadei, Bennemann & Lucena, 2019, p. 3).

Thus, the access of older people to the facilities and possibilities provided by the internet has brought more security and alternatives for communication between peers and family members, even in cases where geographical distance prevents personal approximation. This is the case of grandparents who live in separate homes from their grandchildren.

Coutinho & Rabinovich (2020), using audiovisuals as a technique, recorded the contribution of digital technologies to bring grandparents and grandchildren together, in the face of the isolation barrier. They concluded that “Grandparents showed feelings of affection, care, protection and intergenerational, reciprocal meaning of life, but also the fundamental violation of freedom to come and go” (Coutinho & Rabinovich, 2020, p. 191). The word that defined the feelings of grandparents, in this research, was longing, longing for what was and was not possible to happen during the pandemic: contact with grandchildren.

Another study, called “And speaking of homesickness... grandparents-grandchildren relationship in the new coronavirus pandemic”, by Neves & Rabinovich (2020, p. 200), emphasizes the same point listed above, pointing out in interviews with grandparents, that technology “is being the resource used by grandparents and grandchildren to feel close, despite the confinement”. Through the internet, computer, cell phone, video calls, WhatsApp, the grandparents interviewed revealed that they were able to partially deal with their fears and feelings of loneliness. This study concluded that grandparents re-signified social distancing, finding meanings for themselves in the relationship with their grandchildren, thus mitigating the feeling of homesickness.

Similarly, studies such as those by Ramos, Rabinovich & Azambuja (2020), Coutrim & Silva (2019), Hammerschmidt, Bonatelli & Carvalho (2020), Araújo & Dias (2010), among others, have shown that the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren is permeated by exchanges and playful moments. In addition to the transmission of teachings, values and family memory, the elders play an important role in the lives of their grandchildren, whether affective, material, educational or emotional. With the Pandemic, meetings between grandparents and grandchildren decreased. However, for many people, Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) have made it possible to interact through social networks, such as Facebook, Instagram and voice call, and messaging applications, such as WhatsApp.

With a specific focus on the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren through ICTs, research carried out by Ramos, Rabinovich & Azambuja (2020) showed how the virtual interaction between grandparents and grandchildren can contribute to breaking the separation caused by geographic, cultural, generational distance and communication, strengthening the bonds of friendship and cooperation between the two generations. According to the authors, grandchildren teach their elders how to use new cell phones, download applications, send text, and voice messages, in addition to other actions aimed at communication, thus revealing a process of exchanging and transmitting knowledge of the younger generation, new to the oldest.

Such teachings are not permanent, they change over time, according to the age of grandchildren and grandparents and demonstrate a clear change in the direction of intergenerational knowledge transmission. When it comes to technologies, it is not the elders who teach the younger ones, but the children, adolescents and young people who transmit new knowledge to their parents and grandparents. Intergenerational co-education therefore assumes, in its full form, a two-way street.

Based on authors such as Ramos, Rabinovich & Azambuja (2020), Coutrim and Silva (2019), Hammerschmidt, Bonatelli & Carvalho (2020), Araújo & Dias (2010) among others, this article brings as a backdrop the changes in relationships between grandparents and grandchildren during the pandemic and the importance of technology in reducing the impacts of social distancing between these two generations, who learn and teach each other throughout their lives. Thus, the main objective of this study was to investigate how a group of grandparents from different regions of Brazil use technology to communicate with their grandchildren during the Pandemic.

1. Methods

The investigation was carried out during the Pandemic period, in 2021, and was configured as a descriptive, exploratory, and qualitative study. The data were constructed from the application of a semi-structured questionnaire with closed and open questions prepared through Google Forms and sent virtually to the selected grandparents. We applied the questionnaire to people from different states, seeking to capture whether there was an interference of different cultural contexts in the respondents' understanding of living with their grandchildren in times of Pandemic.

The multiple-choice questions sought to know general aspects of the participants, bringing information about gender; age group; educational level; profession, type of residence. Questions were also formulated whose objective was to know the profile of the grandchildren, such as age group; schooling; geographical distance from the grandparents' residence; modality of coexistence; type of face-to-face and virtual contact. There were three descriptive questions and, by offering more space for respondents to express themselves, they aimed to capture more comprehensive information about the teaching and learning process through ICTs between the two generations. The questions were: “How do you use the internet to teach?”; “What do grandchildren teach you on the internet?”; “How do you feel about teaching and learning with grandchildren in a time of a pandemic?"

1.1 Sample

For the choice of participants, a purposeful sampling was used. In this type of sampling, according to Turato (2013), the researcher deliberately chooses the participants who will compose the study according to the objectives of the work.

The selection of research participants took place in different contexts; however, the predominant professional environment was the university. Sampling was carried out by indication of the selected ones, a procedure called “snowball” (Turato, 2013). According to this sample, the participants themselves indicate people from their circle of contact who fit the selection criteria to participate in the research. The snowball has a limitation, which is the low socioeconomic and cultural diversification of the participants, since the nominees are part of a circle of friends and, consequently, tend to belong to the same social class. However, such a methodology has the advantage of enabling contact with individuals who bring information relevant on a single theme, that is, who experience a specific reality and can answer the central questions of the research. In this case, we are specifically looking for grandparents who maintain virtual contact with their grandchildren during the COVID 19 Pandemic.

As selection criteria to participate in the research, the following were established: Being a grandmother or grandfather and living with grandchildren in person and virtually. Respondents were identified with fictitious names starting with the letters of the region and numbering. Thus, their names were preserved, and their identities kept confidential, as established by the Research Ethics Committee.

People of both sexes were selected through snowball sampling, as has been already said, a non-probabilistic sampling technique where individuals selected to be studied invite new participants from their network of friends and acquaintances living in the south, southeast, midwest, and northeast regions from Brazil. Altogether 15 grandmothers participated in the research. Although there was no selection by gender, only two men agreed to answer the questionnaire.

1.2 Data collection instruments

For data collection, a questionnaire was prepared with closed and open questions and sent by WhatsApp directly to the participants. All were informed that the collaboration would consist of answering a form on the relationships between grandparents and grandchildren in times of Pandemic. Before sending the questionnaire, the researchers emphasized that the grandparents were not obliged to answer all the questions and it was informed that the identity of the participants would be preserved. Then, all those who agreed to collaborate with the research signed the Free and Informed Consent Form online, on google forms.

1.3 Data analysis

For data analysis, the answers to the questionnaire were grouped by categories, according to the content analysis procedure (Bardin, 2015), which allowed the construction of descriptive tables. These groupings made it possible to search for the similarities and differences observed in the categories. Thus, it is worth mentioning that this study looked for similar behaviors among grandparents who answered the questionnaire, but also for some peculiar and discordant aspects in their answers.

2. Results and discussion

We present below the analysis of the research data. Intergenerational coexistence was considered based on the following categories: (I) General data about the participants; (II) Intergenerational transmission; (III) Coeducation.

2.1 I. General data about the participants

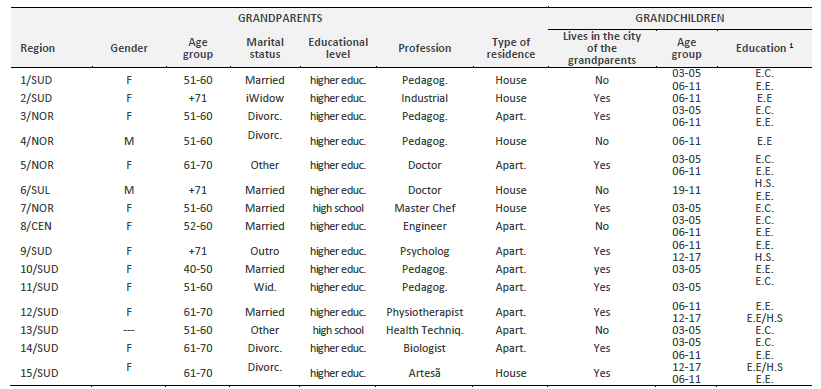

The results were organized around the terminology used by grandparents to understand the content on which they relied to provide their answers. Table 1 presents a general characterization of the grandparents participating in this research and of the grandchildren with information about the region of Brazil in which they live, gender, age group, education level, profession, and type of residence.

Table 1 General data of the grandparents participating in the research and their grandchildren, Brazil, 2021

Note: NOR = Northeast, SUD = Southeast, MID= Midwest, SUL= South | 1 Education: E.C. - Early Childhood - E. - Elementary Education - H.S. - High school

The research participants present characteristics of gender, age group and schooling quite homogeneous. As already mentioned, the vast majority are women. We obtained the participation of two men and one person who did not want to identify the gender. The predominant age group is 61 to 70 years old; the most frequent marital status is married (six cases) and divorced (four cases). Most have completed higher education (12 cases) and all are active in the job market. The age range of grandchildren varies between three and 16 years old. In most cases, the grandchildren live in the same city as the grandparents and coexistence takes place in face-to-face and virtual spaces.

We emphasize, even suggesting new research, the emergence of the other categories, both referring to sex/gender and marital status.

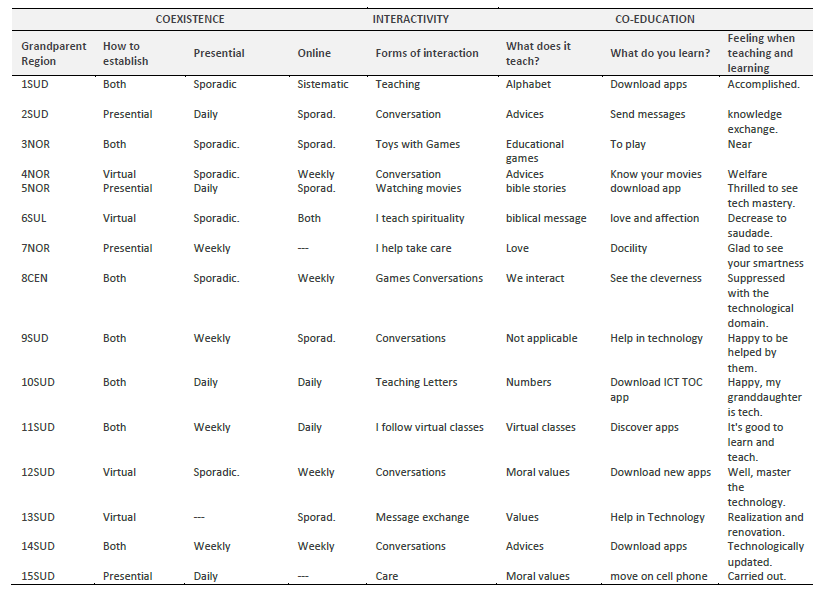

Below, Table 2 provides information on the way grandparents and grandchildren live together and co-education between the two generations, which will be analyzed in the following topics: intergenerational transmission; forms of interaction and co-education.

Table 2 Coexistence,Interactivity and Virtual Co-education of Grandparents Participating in the Research and Their Grandchildren, Brazil, 2021

Note: Note: NOR = Northeast, SUD = Southeast, MID= Midwest, SUL= South | Education: E.C. - Early Childhood - E. - Elementary Education - H.S. - High school

Contacts between grandparents and grandchildren were categorized as a type of sporadic care - when they occurred sporadically, without a systematic forecast for them; type of systematic care: when they occurred systematically, associated with defined activities, such as taking them to school; type of integral care: when they occurred every day. In the classification below, terms used by the participants were maintained, and the type of daily care can be assimilated to integral, weekly to systemic, while the sporadic nomenclature implies a type of sporadic care. These diverse timings imply in different modes of caring.

2.2 II. Intergenerational transmission: forms of interaction

In a family group, the meaning of transmission gains the status of crossing a particular history, circumscribed events and ties established from one generation to another. As can be seen in Chart 2, the form of interaction most evidenced by the research participants was: conversation (6 cases); teaching (5 cases); games/games (2 cases); watching movies (1 case); care (2 cases); monitoring in classes (1 case).

In the three cases in which the contact occurred only in person, in two of them care was mentioned as a form of interaction and, in two of them, the meetings take place daily and, in the other, weekly, that is, the face-to-face meetings would tend to occur frequent way. These data confirm the study by Azambuja (2021) in which grandparents who take care of their grandchildren in an integral way tend to care for their grandchildren.

Comparing the modes of encounter - integral, that is, daily; systematic, weekly; and sporadic, with no date set for the meeting to take place - it can be said that, when only face-to-face meetings occur, they happen more frequently than the other types. Grandparents who occupy themselves sporadically would play more with their grandchildren, confirming the findings of Azambuja (2021).

Overall, the results show that the interaction between the two generations occurs mainly in playful moments, in which conversation, games, games and movies predominate. We draw attention to the teaching situations (4 answers) and class monitoring (1 answer). Such cases can be explained by the high level of education and profession of the grandparents participating in the research, which facilitates communication and monitoring of the grandchildren's schoolwork.

Literature shows that conversations and interactions between grandparents and grandchildren have a different temporality from the relationship between parents and children. In several cases, the older ones are retired and have more time for care and exchange of experiences. Therefore, grandparents, and more specifically in the case of this research, grandmothers, bring a valuable contribution to the family nucleus, offering teachings, care, dialogue, and entertainment to the youngest (Aboim & Vasconcelos, 2009).

Some responses from grandparents who met in person with their grandchildren show the routine and form of interaction:

“It is a very rich experience. Although we are indoors, in this time of a pandemic, we seek to provide her with all comfort and attention. All attention is focused on her. I am seeing her develop every day, in all aspects. She woke me up to a new phase of my life. I go back to the time when I had my daughter and try not to make the mistakes I made in the past. I read storybooks and that way, I'm very happy. Although at the end of the day I was very tired. But when I go to sleep, I comment to my husband, 'Our granddaughter is very beautiful'. It's worth it” (2LDS).

“My day is filled with housework and taking care of my 8-year-old grandson, in this time of pandemic the routine has not changed except the habits of going out often has changed” (15LDS).

We observed from the testimonies, that the Pandemic changed behaviors and required grandparents and grandchildren to create new physical contact strategies.

“We are very close, we initially experienced isolation, we spoke virtually, but it was not possible to keep our distance. We decided to stay together on the weekends, as usual. Using masks when closer. Expanding hygiene care. I take the opportunity to reinforce literacy, through educational games” (10LDS).

We also noticed variations in the contact from one grandchild to another and changes in the approach, according to the age and personality of each one.

“With the 5-year-old, I play and talk. The 13-year-old helps me when she comes to stay with me and we have a lot of conversations because we are very close and the 15-year-old also helps and talks, however, less than the 13-year-old” (12LDS).

We note that the role of the grandparent participants in the research is not limited simply to care. In addition to the instrumental mission that stems from the satisfaction of children's basic needs, grandparents ensure other functions, such as playing, talking, teaching, telling stories and going for walks, also receiving the support and support of their older grandchildren.

This type of relationship is based on attitudes of protection, development, communication, openness to the world, preservation of family history and imagery, companionship, and organization of grandchildren's free time (Ramos, Rabinovich & Azambuja, 2020).

2.3 III Co-education

Literature shows that the co-education of grandparents and grandchildren is rich in social contact, mutual teaching, respect, and appreciation of the other (Azambuja, Ramos, Rabinovich, 2020; Coutrim and Silva, 2019).

When looking at Table 2, we found that grandparents learn from their grandchildren operations related “to handling electronic equipment and the internet: downloading applications (1SUD; 10SUD; 11SUD; 12SUD; 14SUD); using cell phones and computers (2SUD; 9SUD; 13 SUD; 15SUD).

The cleverness of the grandchildren is impressive”, declares 7NOR when exclaiming her admiration. We are, in fact, immersed in a technological generation. The grandchildren have greater management and skill with technologies and have already established relationships in this context from a very early age; however, in this relationship there can be interaction/communication; cooperation and trust, making this relationship between the two generations strengthened over time by the proximity and complicity between family actors, who dialogue in cyberspace and strengthen affective and intergenerational bonds (Azambuja, Ramos & Rabinovich, 2020; Fuchsberger et al. ., 2021).

Some answers from grandparents show this and emphasize cooperation: “My 15-year-old grandson is the one who helps me in professional activities (9SUD)”.

The conversation about mobile applications also appears, since they are part of the daily lives of children and young people.

“When we talk, he always surprises me by wanting to know if I already have “such” app. Hence our conversation is at this level of teaching and digital updating” (14LDS).

The creation of videos is also a topic of interaction between the two generations:

“My 5-year-old granddaughter asked me: Grandma, do you have Tic Toc on your cell phone? I said no and then she took my cell phone, she asked her mother to put the address of the application and she downloaded it with the greatest ease” (10LDS).

We perceive here knowledge, domain, and support characteristic of this cybernetic generation. Children and young people are quicker and easier to handle electronic equipment and “navigate” the internet and teach their grandparents, while grandparents transmit moral (LDS 12; 15LDS) and spiritual (LDS 6) values to their grandchildren. “I talk weekly with my grandchildren and with the eldest I advise them; it is the eldest who have this mission and, as a grandmother, I fulfill my role of counseling” (12LDS). Strengthening family ties is a concern of the elderly:

“It's an opportunity to be together, strengthen relationships and teach how to sit at the table, be careful with language, watch TV and sleep. I usually encourage reading, writing, mathematics and stimulate some talent, in my case, drawing” (15LDS).

The research also revealed that such concerns with the maintenance of family ties and moral values are independent of the age of the grandchildren.

“I have grandchildren of different age groups: 32, 30, 19 and 11 years old. We talk daily through zap and minister about faith and pray with them. Before the pandemic, the elders were more resistant, now they are more receptive to the Word” (6SUL).

Indeed, the Pandemic has produced strong individual and collective impacts, not only at the level of physical and mental health, but also at the social, economic, and family level. And it is at the origin of major impacts and reinforcement of loneliness and social isolation of the elderly and grandparents being the most vulnerable and at risk of this new virus (Ramos, Rabinovich & Azambuja, 2020).

Therefore, we seek to understand how grandparents feel about teaching and learning with grandchildren in pandemic time. We found that there was a rapprochement in the relationship:

“The pandemic made me get closer to my granddaughters so that my daughter and son-in-law can work. It is very good to learn and teach, an inexplicable exchange of care and affection” (10LDS).

“I feel close, even though I don't live with my son and daughter-in-law. I get emotional when my three-year-old granddaughter calls me. My daughter-in-law tells me that she takes out her cell phone, locates my photo and clicks on the phone with the greatest ease” (8CEN).

We could see the admiration and a certain gratitude of the grandparents in the face of the ease with which their grandchildren handle digital technologies. The exchange of knowledge is clear between the two generations:

“It's very pleasurable. Sometimes I think I learn more than I teach. I am very happy to share my stories and experiences with my grandchildren. We live in totally different worlds. Their eyes sparkle as they hear me tell stories from my childhood. At the same time, it's wonderful they tried to teach me how to send a message by cell phone” (15LDS).

As we can see, the use of information and communication technologies integrate the daily lives of grandparents and grandchildren, configuring a new way of relating and interacting in contemporary times. In this sense, we agree with Daró (2018) and other authors presented in this article when stating that not only the elders have a lot to teach the new generations, but also the young people have been teaching the elders to use and live with these complex technological novelties. One of the great attractions of the internet in contemporary times is the social networks that have increasingly allowed the interaction and establishment of what is called “virtual relationships”. Without renouncing their role as “counselors” and as people in charge of transmitting teachings, memory and faith to new generations, today's grandparents are receptive to the lessons of the youngest and with admiration and pride recognize the new knowledge taught by grandchildren.

Conclusion

This research brings important reflections on the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren during the Pandemic. Fear and insecurity were present in all nations and both grandparents and grandchildren have experienced difficult days, not previously experienced by these generations.

Since March 2020, with the arrival of the Coronavirus Pandemic, grandparents and grandchildren have been forced to maintain social distance and traditional forms of personal interaction and demonstration of affection such as hugs, kisses, and caresses, so present until then in their relationships, became rarer. These were times of loss, pain, and insecurity. Many grandchildren lost their grandparents to COVID 19, and grandparents also had to say goodbye to their grandchildren. However, in addition to the Pandemic, the relationships between these two generations remained, bringing diverse benefits to both, as the authors cited in this article reveal to us.

The elderly are more focused on communication technologies and have sought interaction, entertainment and sociability with their friends and relatives through the internet, accessed by their smartphones. We can venture to say that, even after the end of the Pandemic, there will be no setback in the uses of technologies by the elderly.

The data brought by the research showed us that the investigated grandparents maintained the relationship and exchanges with their grandchildren; however, virtual contact increased, and interaction took place through technologies. Most of the participants in the sample were women with a high level of education and still working professionally, which facilitates interaction with ICTs. The age of the grandchildren also varied; however, the answers provided in the questionnaires show that, regardless of age, grandchildren use virtual tools more easily and quickly than grandparents. Such easiness in the handling of technologies by such young children causes astonishment and admiration to the elders. We can see from their answers to our questions that their grandchildren surprise them daily with new skills and knowledge about applications, movies, resources, and information present on the internet. And all this knowledge and information becomes subjects for conversations between the two generations.

We did not find differences in the behavior of grandparents from different regions of Brazil and one hypothesis for this result is the fact that there is a certain homogeneity in the participants' education and professional activity. There was also no distinction in the behavior of the two men interviewed in relation to that of the women.

Regarding the interaction between grandparents and grandchildren, we observed that this occurs mainly during leisure time: to play virtually, talk, watch movies, etc. However, research participants also help their grandchildren in their schoolwork and transmit religious, moral, and behavioral values.

In relation to the feeling about co-education, all the interviewees revealed that it is of great pleasure and admiration for the technological mastery on the part of children and young people and affirm that technology allows the approximation and intergenerational exchange. Such results reinforce what was pointed out by authors as Ramos in Azambuja (2021), when they recognize the importance of intergenerational and family solidarities for active aging to help in mental health of both, for the personal fulfillment of grandparents and for the grandchildren's quality of life.

In summary, we recognize that the sample of this research is limited, but the results provide relevant information that allow us to affirm that intergenerational co-education remains, regardless of the form and environment in which it occurs. Each day, grandparents and grandchildren look for different ways of interacting, exchanging words of teaching and mutual help. The Coronavirus Pandemic demanded new learning from everyone to maintain social bonds and we could observe that participating grandparents and grandchildren reinvented themselves and learned new ways to relate. However, care and affection that permeate such relationships remained, whether in face-to-face contact or through the virtual world.