Introduction

Married women may decide to work for several reasons such as self-actualization or finances. Having a career makes women more independent, capable of improving family welfare, and generating economic resources. However, working in the public sphere also divides some women between two roles: professionals and family caregivers. This division doubles their burden as they must continually shift between their roles and duties. Not only do they have to climb up the career ladder, but they also need to cater to their family and domestic chores.

A study by Heikkinen, Lämsä and Hiillos (2014) asserts that working women emphasize on being independent; they generally hold various roles and do not solely rely on their husbands for monetary matters as they earn their own incomes. Furthermore, they seek to advance their careers as a form of self-actualization. These two roles attached inevitably result in their growing responsibilities.

Previous studies have shown that working women shoulder a double burden from their professional and domestic work, either paid or unpaid (Ji et al., 2017; Ferrant, Pesando and Nowacka, 2014; Rao, 2018). Domestic work seldom generates financial resources, making it a particular burden especially within marriages where wives are fully responsible for household chores without support from their husbands. Women, especially in traditional societies, invest far more time into the family and household than men, resulting in a gigantic trove of unpaid labor that is sustained by women. Shafer (2011) also states that wives bear most of the household burden even when they combine professional work with family responsibilities.

Many women feel that household work and traditional roles are inadequate, so they choose to work in the public sphere (Toffoletti and Starr, 2016; Offer and Schneider, 2011; Blair-Loy et al., 2015). In contemporary society, working women reflect women’s independence and strength in improving the welfare of the family. Modern society also believes that professional work and domestic duties go hand-in-hand; however, studies show that women and their families are still unable to balance the two because of problematic gender roles. Ouellette and Wilson (2011) found that working women assume gendered responsibilities while supporting healthy families. In addition to tending to their professional work, they are also burdened with maintaining the health and wellbeing of their families.

As long as there is no true and equal collaboration between spouses, this double burden will persist. Without acknowledgment or approval by nuclear and/or extended family for a partnership marriage wherein both partners share a more equal distribution of responsibilities, even highly educated women will continue to carry an unequal level of responsibility in all spheres. Previous studies highlight this double burden experienced by working women to encompass responsibilities toward extended family members as well (Sidani and Al Hakim, 2012; Gough and Killewald, 2011; Ali et al., 2011), creating additional roles and duties.

Oshio, Nozaki and Kobayashi (2012) found that the unequal division of domestic work can affect marital satisfaction. Working women often complain of being tired of working outside while being burdened with domestic chores. Further, husbands and children rarely help with domestic chores, citing various reasons, including the view that domestic chores are a woman’s duty. This imbalance often triggers quarrels between the couple as wives find themselves drowning in too many responsibilities. Sasaki, Hazen and Swann Jr. (2010) further states that professional work for mothers is like a double-edged sword; on the one hand, it develops women’s competence, but on the other, it erodes such competence if their spouses do not share domestic responsibilities.

Having a professional job in the public sector is a joy for some women as it can foster a sense of independence. Working women can gain their own income which helps in feeling satisfaction. Despite the additional household income used to improve the family’s economic conditions, working outside the house can reduce women’s happiness due to a lack family time (Mencarini and Sironi, 2010). Similarly, if women decide to prioritize their families, their professional performance may decline. As a result, working women are held to the expectation of performing well on both fronts. Previous studies suggest that women often experience the disproportionate double burden of balancing work with their household duties (Procher, Ritter and Vance, 2017; Miettinen, Lainiala and Rotkirch, 2015; Foster and Stratton, 2019). The division between work time and family time is often unequal for these women, creating problems that increase if they do not have adequate support from their families.

Nilsen et al. (2017) highlight that there is a gender gap inherent to the double burden as most women spend more time caring for their families than men. Even when both parents work, the task of caring for the husband and children remains with the woman, a trend widely found in the majority of Indonesian society as it accompanies Indonesian customs and cultural values. This double burden can be seen as an obligation, especially in traditional societies (Brickell, 2011; Pološki Vokic, Obadic and Sincic Coric, 2019). This gender gap is felt when women cannot find time for themselves as they are preoccupied with domestic affairs in a non-collaborative marriage.

Education can also enhance this double burden. Although not the main cause, women’s education levels can directly affect their partnerships with their husbands, i.e., women with lower levels of education feel a heavier sense of responsibility toward their spouses and families (Ruppanner, 2009) and are less likely to be valued by their husbands and extended family and do not have promising and satisfying career opportunities. Women with higher education levels are more aware of gender issues and dynamics, enabling them to create a partnership marriage and reduce this double burden. Moreover, in gender conscious contemporary societies, both spouses are highly educated and domestic duties rarely escalate to a point of creating serious problems within the family structure. Heijstra, Steinthorsdóttir and Einarsdóttir, (2016) states that women seem to always be “running out of time” because they are torn between performing two roles.

Chen et al. (2017) show that women’s double burden decreases as children get older and become more independent, and when husbands offer support by participating in domestic chores. However, some studies suggest that the increase in men’s participation in domestic works is comparatively insignificant in mitigating women’s dual roles (van Hooff, 2011; Bianchi et al., 2012; Helms et al., 2010). Even when men increase their domestic participation, this does not entirely replace women’s childcare role and the associated burden. Additionally, studies also emphasize that because of multiple responsibilities, women’s leisure time is of lesser quality than their counterparts (Qi and Dong, 2013; Xhaho, Çaro and Bailey, 2020; Stalker, 2011).

Studies on women’s double burden are common and easy to find. However, the workload of female elementary school teachers whose own children are enrolled in elementary schools is difficult to find. Elementary school age children require parental attention and guidance even during online schooling as they are not as independence as older children. This research is compelling because it focuses on female teachers who had to continue working in the midst of the obstacles brought about by the pandemic on top of already being stretched to the bone.

Research method

This is a descriptive mixed method research study carried out in the province of East Java, Indonesia. The study sample involved 374 female teachers, 212 of whose children are currently studying at the elementary level. Data collection was carried out through structured interviews and a few respondents were interviewed face-to-face and others by phone, as not all respondents were comfortable being interviewed in person due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) precautions. Additional in-depth interviews were conducted with the respondents that has unique and interesting cases in relation to the double burden they experienced, especially in terms of teaching online classes. The in-depth interviews aimed to gather as much information as possible about their workload regarding online schooling during the pandemic and their husbands’ participation in domestic chores.

Results and discussion

During the pandemic, all educational institutions in Indonesia shifted their teaching and learning processes to an online format, affecting both teachers and students. While teaching online, teachers faced a number of obstacles ranging from poor internet connection to students’ ability to understand the lessons.

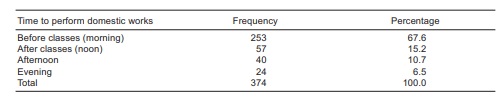

Respondents’ workloadtable 1

Although they provided additional facilities for their children, some teachers were conscious of their children’s learning while they were busy with their own teaching activities. Interview data highlights that 49.5% of respondents expressed concern about their children’s learning under these conditions. The teachers felt sorry for their children because they were unable to give their full attention to assist their children’s online learning. Interestingly, 50.5% of respondents stated that they did not worry about their children’s learning despite having their own teaching jobs as they were able to teach them after their classes ended, or because other relatives’ took up this task.

Previous studies suggest that women’s household burden increases when they have children under 16 years of age (Windebank, 2010; Tower and Alkadry, 2008; Bernardo et al., 2015) as they need more intensive care, nurturing, and learning assistance from their parents. With online schooling, children under 16 need parental supervision and guidance, requiring parents to allocate sufficient time for them. The respondents expressed that they spend a lot of time providing care as mothers and wives. Even when both parents have jobs, husbands spend less time with children than their wives, especially when the children are sick (Maume, 2008; Allen and Finkelstein, 2014; Haddock et al., 2006). The women therefore, face more of a burden than their husbands due to having more varied duties and roles.

Striking a well-balanced time management strategy is a challenge for female teachers. Navigating dual roles can create problems for women when their families do not provide a safe and comfortable place, resulting in conflicts, lack of time with children, illness, and stress (Rizkillah, Sunarti and Herawati, 2015; Anwar, 2015; Darmawati, 2019). Without a good family support system, women can suffer from heavy burdens and imbalances. The absence of an egalitarian partnership also affects how women care for their families. Previous studies have found that the division of domestic labor goes well before having children but that the presence of children results in a deviation from this balance (Klumb, Hoppmann and Staats, 2006; Lesnard, 2008; Duvander, Ferrarini and Thalberg, 2005). This deviation is caused by the accumulation of women’s duties after childbirth as childcare is centered on the mother.

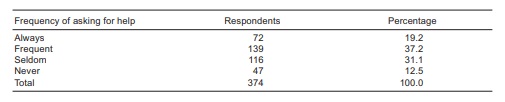

During online learning, children are usually accompanied and assisted by their parents or other people. During the interviews, 53.3% of respondents stated that their husbands helped their children study, while 46.7% admitted that their husbands did not. Usually, the mother accompanies the children during study, so the husbands’ assistance is seen as a choice. Few respondents were successful in collaborating with their husbands to mentor and supervise their children’s learning.

Husbands’ involvement in childcare is an important part of creating an egalitarian family. In Canada, France, Norway, and the United States, husbands perform several domestic duties but do not spend as much time as their wives (Treas and Lui, 2013). Even so, this contribution eases the wives’ domestic burden and can create egalitarian husband-wife relationships while simultaneously reducing conflicts. Offer and Schneider (2011) state that mothers are more involved than fathers in tight time, performing mental works, and managing family activities.

Husbands involved in childcare reflect good partnership. Partnership-based relational pattern between husband and wife can either reduce or create double burdens (Hidayati, 2015). Domestic conflict and psychological pressure on women can be overcome if there is a good relationship between the spouses. Meanwhile, previous studies have found that a double burden is generally experienced by middle to lower class women who struggle from economic pressure, requiring them to work and take care of the household at the same time Ismanto and Suhartini, 2014; Yarsiah and Azmi, 2020; Nofianti, 2016). However, this does not rule out women from other social classes that experience double burden as regardless of class, Indonesian families still adhere to the traditional values of women’s roles in the domestic sector.

When conducting online classes, several respondents revealed that their children would them interrupt to ask questions. Specifically, 48.6% of respondents stated that they prioritized their professional work in these situations, meaning that the respondents asked their children to be patient and wait for them to finish their teaching. Conversely, 32.5% and 18.9% helped their children immediately or redirected them to other people, such as relatives, respectively.

Lee et al. (2018) found that women in South Korea, especially married women, experience a higher rate of suicide because they struggle with the dual burden of managing professional jobs and households. The associated psychological pressure makes it extremely difficult for women to decide what to prioritize, their jobs or domestic duties. In Islam, married women are essentially independent from the responsibilities held by their husbands. However, in practice, cultural factors cause women to bear several burdens (Husni et al., 2015; Suhertina, 2020; White, 2010). This study also illustrated that cultural factors further blurred the divide between professional and personal responsibilities during the pandemic.

Several women are unaware that they experience a double burden because they are accustomed to it (Ramadhani, 2016; Habibi, 2019; Silitonga, 2019); a phenomenon that is especially common in traditional societies where domestic duties are considered a women’s obligation. At the end of the day, women who experience this double burden are simply left to complain about lacking domestic cooperation from their husbands. Further, the social system in traditional societies has not been able to provide a comfortable space for career-oriented women. Conversely, Eastern European countries have accommodated working women by reducing the double burden through institutional arrangements, job security, and low pressure competitions (Matysiak and Steinmetz, 2008; Bauer and Österle, 2016; Ghodsee, 2014). Unfortunately, the social system in Indonesia still adheres to traditional cultural values and is not keen on women pursuing careers.

Apart from assisting and caring for children, women are responsible for cooking. Even though the respondents were burdened with multiple tasks, they were still required to cook for their families. From the sample, 76.5% respondents cooked for the entire family, 1.6% revealed that their husbands cooked, 16% stated that an extended family member cooked, and 2.1% had domestic helpers that cooked. The remaining 3.8% bought food from outside.

Every day I prepare food for my family. Even during this pandemic, I still cook. There are also more household chores because you have to clean the house, look after children, and do teaching jobs. Between working hours and domestic assignments: it gets messy. [Yun, 32 years old]

My husband and I are used to cook together. So during a pandemic like this, I am not too overwhelmed. We are used to sharing tasks. When we don’t feel like cooking, we buy prepared meals. [Tin, 27 years old]

The results indicate that cooking is still the primary responsibility of the women. Even though the professional duties of teachers have increased with online schooling, domestic roles and duties remain consistent. Anwar’s study (2014) states that balance between professional work and domestic duties is crucial to obtain job and family satisfaction, hinting toward the fact that the husband’s support in domestic duties is crucial as they can help create egalitarian values in the family. However, this study contradicts previous studies which state that the husbands’ role in dual-career families in terms of household care and upbringing is greater because dual career families have a clear division of duties (Chesley and Moen, 2006; Ho et al., 2013; Hammer et al., 2005).

Raley, Mattingly and Bianchi, (2006) state that dual career families can be more egalitarian than single breadwinner families; however, this is not necessarily possible for all families. Although the respondents’ families are dual career families, domestic duties remain the dominant responsibility of the wives. Therefore, the manifestation of egalitarian values needs to be more well defined. Social change leads to the formation of dual career families in which egalitarian gender values are held by both partners (Minnotte, Minnotte and Pedersen, 2013). However, social change, hindered by Covid-19, has not been able to create more egalitarian values in the family.

Women tend to avoid conflicts with their husbands regarding the division of labor for the sake of maintaining a peaceful marriage (Bartley, Blanton and Gilliard, 2005; Grönlund and Öun, 2010; Offer and Schneider, 2011). Women do not want to get into fights simply because they are overwhelmed with domestic duties. This in turn increases the burden faced by working women as they allow the problem to continue without negotiating with their husbands. Dual career families are at risk of family conflict, psychological pressure, and decreased quality of marriage, especially in couples with working shifts and school age children (Chait-Barnett, Gareis and Brennan, 2007).

Respondents’ strategies during Covid-19

At times, teachers prioritize their professional work as they consider it a professional obligation.

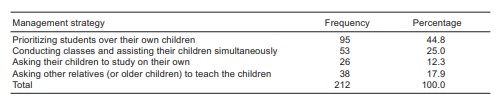

Based on table 2, female teachers have various strategies for managing time between conducting classes and accompanying children in study. This was done so that their professional teaching duties were not disrupted.

I carefully manage the time for work and for children. I prepare the children’s needs in the morning, and they are ready to take part in online learning. Meanwhile I am preparing to teach. I will accompany my child in the evening, when my teaching duties are finished. [Ira, 36 years old]

Once I finish giving assignments to students, I get back to accompanying my child in study. Assessing his works, whether they are correct or not. But I still monitor the PC that I use to monitor whether my students have difficulties or not. [Dyn, 40 years]

Table 2 Respondents’ strategies for managing professional work and assisting their own children in studying

Online schooling has an undeniable influence on the families of teachers. Wheatley’s study (2013) states that the combination of various duties carried out by women becomes a point of time pressure, especially for women with children. In many instances, women must adjust to the professional work of their husbands, not the other way around ( Känsälä, Mäkelä and Suutari, 2014; Delina and Raya, 2016; Motaung, Bussin and Joseph, 2017) Aarseth and Olsen’s (2008) demonstrate that some women do not like to be assisted in household chores because they view their work as an obligation and believe that they are better at it than men; however, this reluctance to accept help becomes a burden. This is also true for women who believe that parenting is better handled alone. Previous studies show that women are burdened by family care as women dedicate more time than men (Wheatley, 2012; Wheatley, 2014; Quek and Knudson-Martin, 2008). In patriarchal societies, work is sexually segregated and domestic work is largely assigned to women. Interestingly, some respondents stated that their husbands helped with housework, especially during the pandemic. Meanwhile, few respondents stated that their husbands did not contribute to domestic chores.

My husband and I try to share our duties. I cook and take care of the children, my husband cleans the house. As for accompanying children in study, we take turns. My husband and I do this to balance our work and avoid burnout. My husband also doesn’t demand that I have to do a lot of housework. Whenever we are tired, my husband and I don’t cook. We decide to buy food. [Fia, 30 years old]

Since young, I’ve been educated to be a good housewife. Women in my family perform household chores by themselves. Sometimes I feel tired, but what can I do? This is this my duty as a woman. Sometimes I also ask my husband to do household chores, but it’s just small things like moving things. My husband also never does house chores, maybe because this is the culture in our family. [Bin, 40 years old]

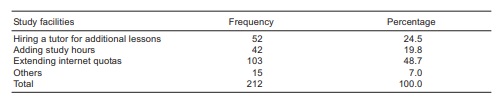

If women reside with extended family, the family also plays a role in creating a double burden on women. The double burden for women is triggered by the absence of a good support system and awareness about the gendered division of labor (Amin, 2016). Both women and men can carry the double burden, depending on the length of time spent completing unpaid work (Wierda-Boer et al., 2009; Gershuny, Bittman and Brice, 2005; Henz, 2010). Dual career families also experience a role overload where a person feels that a particular role’s demands are increasing over time (Higgins, Duxbury and Lyons, 2010; Demerouti, Bakker and Schaufeli, 2005; Nomaguchi, Milkie and Bianchi, 2005). Table 3 highlights the ways in which the respondents’ provided additional resources for their children.

Women in dual career families do not only work because of economic reasons but also as means of self-actualization to utilize the education they have achieved (Oktorina and Mula, 2010). However, economic reasons outweigh reasons of self-actualization. Gender equality can be realized in dual career families when there is no debate over who is the primary versus secondary breadwinner because both partners balance their career and family duties (Puspitawati, 2009). With household chores, women may ask for help from their husbands (table 4).

Zayyadi (2012) states that being a career-oriented has a negative impact on women because they are busy managing two things and consequently put their own human needs aside. When domestic affairs become a two-party affair between the spouses, women can balance their professional and household roles without feeling burnt out. Dual career partners in Finland share household duties more equally than partners in other countries (Fahlén, 2015). This is not surprising since Finnish culture is more open to egalitarian values unlike Indonesian society.

Although women’s double burden is difficult to completely avoid, it can be mediated better. During this study, 41.3% of respondents actively negotiated domestic roles between the spouses, while 58.7% were unable to negotiate the same. The ideal household is one in which members can negotiate their roles. The absence of role negotiation, however, automatically makes women’s double burden difficult to solve.

Abele and Volmer indicate several problems in dual career families such as priority for one job, a sense of dissatisfaction with household duties, a sense of overwhelming with work and duties, and stress. These things are brought on by the absence of role negotiation between the partners. Dual career families cannot guarantee a balance of work, family, and personal time (Neault and Pickerell, 2005). Mayangsari and Amalia (2018) states that work-life balance is an important factor for working women because if women dedicate more time or energy to one side of the duality, conflict could occur.

Conclusion

Teachers, especially women, face several challenges due to online schooling that are in turn intensified by the inherent intersection of work and family. The domestic duties of female teachers keep on increasing when their own children are engaged in online learning.

In terms of domestic duties, some women are forced to continue performing household chores even while they work full time. Besides having to assist children in learning, they must also manage their time to efficiently and successfully fill both their professional and familial roles. Sometimes women must work all day, performing domestic work in the morning (before teaching), during the day (post teaching), in the afternoon, and even at night.

Some female teachers, however, find it difficult to manage time between their professional work and their roles as mothers assisting school age children. They made various efforts to effectively shoulder both responsibilities, including prioritizing school students over their own children, conducting classes and assisting their children simultaneously, asking their children to study on their own, and asking other relative’s to teach their children during their work hours. Additionally, they also involved their husbands to accompany the children during studying and contribute to domestic tasks. The husband’s involvement in these tasks serves as social support for women. Therefore, it is necessary for partners to negotiate the division of domestic roles so that the burden on women is mitigated and gender equality in the family can be realized.