Introduction

Prison facilities and their associated living conditions - often marked by overcrowding, old and dilapidated buildings and poor sanitary conditions - constitute a particularly vulnerable context to the amplification and spread of infectious diseases (Redondo et al., 2020; WHO, 2021). In addition, the frequent movement of staff and other individuals in and out of prisons increases the risk of infection amplification (Dünkel, Harrendorf and van Zyl Smit, 2022; Johnson et al., 2021; Silva, 2020, 2021). Hence, such contexts are ill-equipped to handle large-scale epidemics or pandemics, as ensuring basic protective measures, hygiene protocols, and social distancing proves challenging. Moreover, the prison population tends to experience more severe health problems compared to the general population (e.g., HIV, tuberculosis, diabetes, among others) (WHO, 2021, 2023). Consequently, the Covid-19 pandemic presented a particularly challenging scenario for prison systems worldwide. Several international organisations have developed guidelines and recommendations to prevent and control the spread of Covid-19 among imprisoned individuals, prison staff and associated communities (Redondo et al., 2020). However, the implementation of these preventive and reactive measures varied significantly across different national contexts (Dünkel, Harrendorf and van Zyl Smit, 2022; Rodrigues et al., 2022a; Maruna, McNaull and O’Neill, 2022; Zeveleva and Nazif-Munoz, 2022).

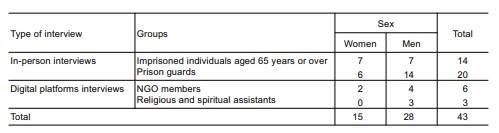

In this article, based on 43 interviews conducted with imprisoned individuals aged 65 or over, prison guards, and NGO representatives and religious and spiritual assistants engaged in the prison context, we explore the implications of the Covid-19 pandemic in the Portuguese prison system. More specifically, we investigate (i) the impacts of the pandemic-related imposed restrictions on activities and social relations of imprisoned individuals; (ii) the controversies surrounding the implementation of protective measures, such as mask usage, (iii) the paradoxical repercussions of Law 9/2020, which introduced an early release scheme, allowing the release of approximately 2000 imprisoned individuals from the Portuguese prison system. Our data illustrate how the Covid-19 pandemic further accentuated the “depth of imprisonment” (Crewe, 2021), functioned as a kaleidoscope that sheds light on the diverging rationales that characterize the prison system and acted as a magnifying glass that accentuated pre-existing social problems.

The Covid-19 pandemic and prison systems

While social sciences were analysing this exceptional phenomenon in real-time and its associated disruptions and implications, research on the impact of Covid-19 in several social spheres proliferated (Jamil, 2021). However, the prison context has become more opaque and the barriers to access have become, in most cases, insurmountable. The Covid-19 pandemic, therefore, marked a time when the rights and well-being of those imprisoned were most at risk and simultaneously more difficult to scrutinise as oversight mechanisms encountered significant barriers to access (Garrihy, Marder and Gilheaney, 2022; Maculan, 2024). Faced with such constraints, scholars conducting prison studies focused on analysing policies and measures implemented globally to manage imprisoned populations during the pandemic while also adapting data collection techniques to meet social distancing requirements (see Marietti and Scandurra, 2021, and, with regard to the Portuguese case, Silva, 2020, 2021).

In terms of the analysis of policies and measures taken to prevent rapid and large-scale infections in prison settings, there is a substantial body of literature analysing it (Dünkel, Harrendorf and van Zyl Smit, 2022; Klein et al., 2022; Nielaczna, 2021; Redondo et al., 2020; Silva, 2020, 2021; Wahidin, Pane and Angkasawati, 2022; Wegel, Wardak and Meyer, 2022; Zeveleva and Nazif-Munoz, 2022). These studies demonstrate that the most common prevention strategies included: (i) suspension of prison sentences; (ii) implementation of pardons or early release schemes for specific groups of offenders; (iii) interruption of activities within prisons; (iv) restriction of contact with the outside world by suspending visits and prison leaves; (v) expansion of digital communication platforms; (vi) screening of the prison population through swab analysis; (vii) completion of vaccination programmes (Dünkel, Harrendorf and van Zyl Smit, 2022; Esposito et al., 2022; Maculan, 2024; Rodrigues et al., 2022a; Silva, 2020, 2021). In this regard, Zeveleva and Nazif-Munoz (2022) demonstrate that although all European countries banned visits, only 16 implemented early releases or pardons. The authors also observed that countries with prison overcrowding issues acted more swiftly in releasing or pardoning imprisoned individuals, whereas countries with overcrowding but higher proportions of local nationals were quicker to restrict visits.

Besides such a body of literature, some studies have attempted to directly collect imprisoned individuals’ accounts using data collection techniques adapted to the pandemic social distancing requirements. For example, Maycock (2021) developed a participatory action correspondence methodology at one Scottish prison. Suhomlinova and colleagues (2022) exchanged correspondence with transgender and non-binary prisoners in English and Welsh prisons for 12 months, from April 2020 to April 2021. Fontes (2022) corresponded with imprisoned interlocutors in Guatemala in the period between 2020-2021 after visiting privileges were revoked. Maruna, McNaull and O’Neill (2022) worked with a partner organisation, User Voice, to develop a participatory action research project in ten prisons in England and Wales. In particular, they facilitated an accredited two-day “peer research methods” course for 99 prisoners, who then wrote field notes, conducted one-to-one interviews and collected over 1400 completed surveys. Finally, Garrihy and colleagues (2022) participated in a collaboration between the Office of the Inspector of Prisons in Ireland and academics that entailed distributing journals to imprisoned individuals “cocooning” (isolated in certain areas of the prison, confined to their cells for 23 hours a day) due to advanced age or medical vulnerability. During two weeks in April and May 2020, imprisoned individuals journaled about their experiences. Although such methods can be suitable for situations where face-to-face data collection is impossible, it is important to note its limitations in populations with reduced literacy levels, such as imprisoned individuals. In addition, there are also a few studies that collected data through interviews, namely Gray, Rooney and Connolly (2021) in the United Kingdom, and Maculan (2024) in an Italian prison.

Insights from such studies exploring imprisoned individuals’ lived experiences of the pandemic analyse the overall challenges and difficulties that the lockdown has posed for people in custody, as mental health severely deteriorated (Johnson et al., 2021). Research conducted by Maycock clearly demonstrates how the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated the pains of imprisonment. The main difficulties faced by imprisoned individuals related to communication issues, both between people in custody and prison staff, and family and friends, which aggravated feelings of isolation (Maycock, 2021, 2022; Maycock and Dickson, 2021). Gray, Rooney and Connolly (2021), focusing on the experiences of prisoners after completing a 14-day Covid-19 isolation period, highlight how isolation had exacerbated depression, anxiety or feelings of self-harm. The study conducted by Suhomlinova and colleagues (2022) explores the heightening of the pains of imprisonment, demonstrating how the Covid-19 pandemic enforced long isolation periods and provoked the deterioration of relationships among imprisoned individuals and between imprisoned individuals and staff. The authors also note that Covid-19 aggravated further safety deprivations, as “security considerations apparently prevailed over those of prisoners’ health, illustrating the historical contention between the management of risks prisoners pose and the acknowledgement of prisoners’ human rights” (Suhomlinova et al., 2022: 293). Focused on the Guatemala context, Fontes (2022) illustrates how Covid-19 represented both a continuation and intensification of the basic living conditions in prisons. The carceral community’s efforts to make sense of, adapt to, and leverage the constraints imposed by the pandemic created a volatile yet deeply resilient modus vivendi, with severe consequences for the most vulnerable within and beyond prison walls. Garrihy and colleagues (2022) show that despite imprisoned individuals cocooning believing that enforced isolation policies were in place for their protection, feelings of punishment, boredom and despair were amplified, particularly among individuals reporting pre-existing mental or physical health conditions. Finally, Maculan (2024: 14) shows that in the face of a pandemic situation, it was not the protection and care of the imprisoned that prevailed, but rather the suffering, pain, neglect, stigmatisation and further abandonment of the imprisoned.

The Covid-19 pandemic, therefore, reframed the experience of being imprisoned (Fontes, 2022; Garrihy, Marder and Gilheaney, 2022; Maculan, 2024; Maycock, 2021; Maycock and Dickson, 2021; Suhomlinova et al., 2022). Consequently, it is particularly useful to reflect on the new nuances that the concept of “depth of imprisonment” acquired in such a scenario. According to Crewe, depth constitutes “the degree of control, isolation and difference from the outside world” (Crewe, 2021: 336). More specifically, the author notes that:

depth is essentially about the relationship between the prison and the outside world, meaning that an individual’s assessment of the composite impact of forms of restriction, isolation and seclusion within a carceral environment is likely to be shaped by the nature of their existence prior to their confinement and their expectations of the world to which they will return (Crewe, 2021: 338).

This means that understanding depth requires taking into account imprisoned individuals’ life circumstances and relationships before imprisonment, their conditions during imprisonment, and their expectations regarding lifestyles and possibilities upon release. The Covid-19 pandemic, therefore, introduces new nuances to such a “textural experience of the deprivation of liberty” (Crewe, 2021: 352) as it not only profoundly alters the conditions of imprisonment but also influences perceptions of the world to which imprisoned individuals might return.

Despite the richness of the aforementioned studies in providing a rare insight into prisons during the pandemic, there is still an overall scarcity of studies addressing the impacts of the pandemic on imprisoned individuals involving in-person research (Maycock, 2021: 3). This article aims to contribute to expanding such knowledge by exploring how Covid-19 affected imprisoned individuals. In does so in four innovative ways. First, similar to Maculan (2024), it provides a rare first-person account collected through face-to-face interviews during the pandemic, capturing the perspectives of imprisoned individuals on the impact of Covid-19. Second, since the empirical research was conducted in 2021, interviewees had a clearer perspective not only on the short but also the medium-term effects of the pandemic. Third, interviews were conducted with imprisoned individuals aged 65 or over, who are among the most vulnerable populations to the health risks of the Covid-19 pandemic (for further details, see Garrihy, Marder and Gilheaney, 2022). Fourth, this research encompasses not only imprisoned individuals’ perspectives but also those of prison guards, NGO representatives and religious and spiritual assistants engaged in the prison context, thereby significantly enriching the outlook on the implications of the Covid-19 pandemic on prison systems.

The Portuguese case

According to the latest annual penal statistics from the Council of Europe (as of January 31 2023) Portugal has a prison population rate of 118.3 (non-adjusted value, please see Aebi and Cocco, 2024: 33) per 100 thousand inhabitants, which is higher than the European median value, 106.5 (Aebi and Cocco, 2024). Besides, Portugal is one of the countries with a higher percentage of imprisoned individuals aged 65 or over, whereas the length of prison sentences is far above average and that presents one of the highest suicide rates (Aebi et al., 2022; Silva, 2021; WHO, 2023). Regarding prison conditions, reports of the periodic visit conducted by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture clearly indicate that some Portuguese prisons provide inadequate and, sometimes, degrading conditions.1

On February 17, 2020, the first version of the Contingency Plan for Covid-19 in Portuguese prisons was approved (Redondo et al., 2020). In addition to the provisional suspension of all educational, training, work and other activities involving personnel from outside prison contexts (e.g., academic, religious and volunteer activities), one of the primary measures was the provisional suspension of visits in all prisons (Silva, 2020, 2021). Visits gradually resumed in June (with variations between prisons) and by July, they were already occurring in all national prisons (Redondo et al., 2020). Restrictions involved mandatory scheduling, limited durations (up to 30 minutes), maintaining a physical distance (of at least two meters) and requiring imprisoned individuals and visitors to wear masks. Covid-19’s second wave in the autumn led to the reinstatement of the restrictions, which remained in place until 2021.

The use of masks within the prison environment sparked considerable debate in Portugal. In March 2020, interim guidance from the WHO stated that the use of masks was among the preventive measures recommended to mitigate the transmission of certain respiratory diseases, including Covid-19, stressing the importance of combining them with other protective measures (e.g., hand hygiene, social distancing, respiratory etiquette). However, in the early months of the pandemic, the General Directorate of Prisons and Social Reinsertion (DGRSP) initially determined that prisons did not fit the recommendation to wear masks in public spaces. In an interview with Expresso newspaper in November 2020, the then Director stated that wearing masks was not mandatory in the common areas of prisons:

Prisoners are very prone to close fraternisation, to physical touch: either it’s the cigarette or the illicit cell phone that they share, or it’s the bottle, or the clothes or the CDs that they exchange. I have many doubts about the benefits and necessity of wearing a mask inside the prison zone (Franco, 2020).

Soon after, in a statement shared with news outlets, the DGRSP highlighted that “the issue of the widespread mask use inside the prison area is complex, due to reasons very specific to the prison environment”, such as the daily sharing of objects, and “the repetition of social rituals of proximity that nullify the effect of the mask on the community and can turn the mask itself into a focus of contagion and, therefore, a source of potential outbreak”. In addition, it was underlined that, “the culture of peers that is very ingrained in the prison environment has to be considered in the discussion” and “cannot be disregarded” (Mendes, 2020).

It turns out that the Portuguese prison system has a prevalence of collective accommodation spaces, where prisoners are now spending more time, and it is not expected that people sleep with a mask, eat with a mask and spend several hours of the day permanently wearing masks. The prison cannot fail to be compared to a house where people are deprived of their liberty live, confined and suffering strong restrictions, as everyone knows (Mendes, 2020).

Despite such public positions, this decision was reversed in January 2021 and the use of masks in prison common spaces became mandatory (Franco, 2021).

Besides measures implemented inside prisons, on April 8 2020, Portugal approved Law 9/2020, which encompasses four types of early release measures. The first involves a collective pardon of prison sentences for individuals sentenced up to two years or for those serving longer prison sentences with a remaining period of imprisonment of up to two years, provided they have served at least half of their sentence. This collective pardon excluded some serious and violent crimes, such as homicide, domestic violence, and sexual crimes, among others (Fróis, 2020). The second type of early release measure approved by Law 9/2020 was an exceptional individual pardon granted by the President of the Republic to imprisoned individuals aged 65 or over with a physical or mental illness or a diminished degree of autonomy incompatible with their presence in prison during the pandemic. The third modality provided by Law 9/2020 involved authorisations for temporary release measures, which in these circumstances lasted 45 days, renewable for successive periods of the same duration. This extraordinary leave required individuals to remain at home. The final type of early release measures approved by Law 9/2020 concerns the anticipation of parole by a period of up to six months. In line with temporary release measures, the period had to be spent at home (Brandão, 2020; Rodrigues et al., 2022a, 2022b).

The timescale of the process was extremely rapid: less than three weeks after the World Health Organization released its guidelines, the Portuguese government presented its proposal in parliament; four days later it was approved, and the day after that it was promulgated by the president (Fróis, 2020: 26).

As Fróis points out, while this speed of process is impressive, it is important to ask what problems might arise. According to Redondo et al. (2020), 1289 imprisoned individuals were released under the pardon, 701 orders for authorisation of extraordinary administrative leave were issued, and 14 acts of grace were granted. Overall, these measures allowed the release of around 2000 individuals, reducing the nation’s prison population by around 12,5% between January and September 2020 (Aebi and Tiago, 2020; in this respect see also Ishiy, 2020, 2021, 2022).

Methods

This article is part of a broader qualitative research study conducted in Portugal (Pimentel, 2022, 2023), primarily aimed at exploring the experiences and representations related to ageing during imprisonment from the perspectives of imprisoned individuals and professionals. Data was collected from four prisons located in the same geographical region: one women’s prison and three men’s prisons.

Defining at what age an imprisoned individual becomes - and is considered - elderly is an extraordinarily challenging and complex task (Aday, 2003). There is no consensus among researchers, policymakers and prison administrators regarding the age at which a person is considered elderly, and the age limit varies across studies (Aday, 2003). Some studies set the threshold at 65 or older (e.g.Crawley and Sparks, 2005), while others use 60 or older (e.g.Davoren et al., 2015), 55 or older (e.g.Goetting, 1984) or even 50 or older (e.g.Handtke and Wangmo, 2014). The threshold of 50 or older is based on presumption that imprisonment greatly accelerates the aging process (e.g.Handtke and Wangmo, 2014). However, many imprisoned individuals aged 50 tend not to identify themselves or define themselves as elderly (Crawley and Sparks, 2005).

In this study we defined the age threshold as individuals aged 65 or over. This decision is based on the fact that, in Portugal, 65 years correspond to the age used to establish the eligibility of older people for various rights. Additionally, since we interviewed individuals who had been recently imprisoned, the accelerated ageing effects of imprisonment could not be adequately considered in this group.

The study was designed in 2019, but it remained on hold in 2020 due to the pandemic restrictions. Data collection was authorised in prisons in 2021 as restrictions were alleviated. Recognising the relevance of the Covid-19 pandemic for the experiences of imprisoned individuals, particularly those aged 65 or over, several questions on this topic were included in the script. Such data constitutes the focus of this article.

The analysis presented in this article uses data gathered from 43 interviews conducted between January and May 2021. Participants included imprisoned individuals aged 65 or older, prison guards, as well as NGO representatives and religious and spiritual assistants acting in the prison context (see distribution in table 1). Participants provided consent to conduct and record the interviews after being informed of the study’s aim, with their anonymity assured. Fictitious names were used in the analysis section to preserve the participants’ anonymity. Interviews were conducted using two primary formats: (i) digitally, due to the pandemic-imposed restrictions, with NGO representatives and religious and spiritual assistants; and (ii) in-person with imprisoned individuals aged 65 or over and prison guards. In-person interviews took place when permission to enter prisons was granted by the General Directorate of Prisons and Social Reintegration (DGRSP) and agreed with each prison (see table 1). In in-person interviews, strict adherence to social distancing measures was maintained throughout, with all participants wearing masks. The interview script was focused on personal and professional trajectories, perceptions of the implications of ageing during imprisonment, and the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on the prison system.

All interviews were audio recorded, and the recordings were transcribed verbatim. Quotations were translated (from Portuguese into English) and edited as necessary to ensure clarity of language while fully respecting the meaning conveyed by the participants’ words (Bertaux, 1997). For this article, pertinent quotations discussing the implications of the Covid-19 pandemic were coded and underwent multiple readings. These quotations were systematically compared, contrasted, synthesised and coded by theme and thematic category following grounded theory principles (Charmaz, 2006). They were interpreted using a qualitative content analysis approach (Mayring, 2004). In this article, we present quotations that both authors deemed illustrative of each thematic category identified through content analysis.

Results and discussion

Covid-19 and the accentuated depth of imprisonment

Imprisonment lived experiences were profoundly marked by pandemic-related constraints (Fontes, 2022; Garrihy, Marder and Gilheaney, 2022; Maculan, 2024; Maycock, 2021, 2022; Maycock and Dickson, 2021; Suhomlinova et al., 2022). In Portugal, as in other countries, contingency plans to prevent the spread of Covid-19 in prisons included suspending visits, reducing contact between imprisoned individuals, and halting all occupational activities (Redondo et al., 2020). The suspension included professional occupations, socio-cultural and sports activities, vocational education and training, volunteering, and religious activities for an undetermined period. Although such interruption aimed to protect imprisoned individuals, the suspension had severe repercussions on their daily lives. It meant staying for long periods in their cells (up to 23 hours a day) without viable alternatives to occupy their time, as described by both imprisoned individuals and professionals:

With Covid we are much more [time] confined. [João, 68 years old, qualified theft, sentence of two years and six months, imprisoned for a year].

All activities stopped! […] Even the few activities that existed before, like visitors, have stopped. There is no school, there is nothing. [Samuel, NGO member].

As a consequence, feelings of restriction, isolation and seclusion were amplified. As posed by an NGO member:

Prisoners became more imprisoned. They already had little contact with the outside… […] In order to avoid exchange and contacts between different wards, they ended up having much less yard time… [Leonardo, NGO member].

Due to their heightened vulnerability to Covid-19, elderly imprisoned individuals were particularly affected as specific measures were implemented to protect them, namely isolation for the general prison population. As described by an imprisoned individual and a prison guard, this meant that this group was housed together and followed separate routines from other imprisoned individuals:

Me and about two or three others were the confined ones [laughs]. […] Because we eat separately, we’re not together with the others. […] And at the beginning of the confinement, we also couldn’t go to the yard. [João, 68 years old, qualified theft, sentenced to two years and six months, imprisoned for a year].

They were isolated, and I think for a good reason, from the rest of the prison population. We tried to place them there more or less within the same age range, in a proper place, where they would be protected from risk. [Ricardo, prison guard].

Despite the severe impacts of activity suspension and compulsory cell confinement, both imprisoned individuals and professionals agree that the most significant restriction felt as a result of the pandemic-related restrictions was the suspension of visits. As noted in the following narrative, the cut-off of prison visits implied not only a decrease in contacts but also an interruption of the provision of some kinds of material support (such as food, entertainment items, and toiletries) that function as a “cushion” to alleviate the harshness of prison life (Granja, 2018).

The most striking and disruptive impact has been the severance of human relations with the outside: visits from volunteers, assistants and, in particular, families. The suspension of visits has been traumatising. Because for prisoners, family is extremely important. As the prison system is structured, family visits you, brings a little economic help, and even brings a food supplement. The family is the one that brings them comfort and affection… That was the great drama of those prisoners. [Óscar, spiritual and religious assistant]

The heightened feeling of isolation from the prison community, the severed contact with the outside, and the resulting reduction in material support, therefore, potentiated serious emotional challenges for imprisoned individuals (Gray, Rooney and Connolly, 2021; Maculan, 2024; Maycock, 2022; Suhomlinova et al., 2022). According to a spiritual and religious assistant, this situation was further compounded in cases where imprisoned individuals were unable to attend burial ceremonies for relatives who died during the pandemic.

They were prevented from visiting them and that is a loss… I don’t know if in some cases it is irremediable, but emotionally it created serious problems. […] Death also happened [during this period] and will continue to happen, the families that could not visit, that could be present at the funeral… [César, spiritual and religious assistant]

Despite such adverse conditions, prison guards reported being surprised by imprisoned individuals’ reactions to the set of limitations imposed, especially visitation restrictions. Usually, any kind of situation affecting visits (such as prison guards’ strikes) causes significant tumult among imprisoned individuals. However, in this situation, prison guards reported that imprisoned individuals fully understood the need to suspend visits as limitations were being imposed on all spheres of society, as widely communicated by media outlets (for more on this, see Schneeweis and Foss, 2022):

It surprised me because the prisoners accepted it well. […] I thought it was going to be much worse. I thought that the prisoners were going to… They are very demanding and they would rise up against this. [Nicolau, prison guard]

In June 2020, visits were resumed under some restrictions: one weekly visit lasting 30 minutes, limited to two persons, scheduled on weekdays. The resumption of visits also required the adaptation of visiting rooms: acrylic screens were installed in all prisons to ensure physical distance between imprisoned individuals, and the use of masks was mandatory. According to participants in this study, these conditions created further difficulties in the already pre-existing issues relating to communication during visits. Consequently, several imprisoned individuals decided not to resume prison visits, as explained by an imprisoned woman. This decision was based on the high demands that visits placed on relatives, namely travelling long distances, economic costs, and the need to take time off from work.

Before the pandemic, they came. […] Then the pandemic started and that was it because it’s very far. And only two people can enter and it is half an hour. To come and go is almost 500 km! And I think the visits have already started on Saturday and Sunday, but they were only during the week… When they are working, I don’t want them to leave their lives to come here. […] I have a great-grandson, who has just turned eight months old […]. I only know him from photographs… They wanted to bring him here and I said: “No, he’s too little and why should he come? I can’t even kiss him…” [Irene, 65, slavery, sentenced to five years and six months, imprisoned for two years and 10 months].

Due to the suspension and limitations on visits, compensatory measures included changes in the number and duration of phone calls allowed. Instead of the previous 5-minute phone calls, imprisoned individuals were allowed 15-minute calls, which could be used in a single session or split into different calls. They could also contact up to three numbers per day. Moreover, the pandemic accelerated the implementation of a pilot project to install telephones in cells. Under this initiative, imprisoned individuals can use the phone every day for an hour between 7 am and 10 pm. This project, only available in some Portuguese prisons, not only strengthened the connection between imprisoned individuals and their families by allowing more time for contact, more flexibility and more privacy but also contributed to alleviating tensions arising from the use of the phone booths, as stated by the following imprisoned women:

Now we have a telephone in the cell… amazing! It was a great relief because there was a lot of noise because of the telephone. Now it is a sense of peace. [Conceição, 65 years old, drug trafficking, currently undetermined sentence, imprisoned for eight years and seven months].

However, since imprisoned individuals bear the full phone-related costs, these phone calls constitute a significant expense that some are unable to cover (Silva, 2020; 2021).

Now they introduced phones in the cells and we have one hour per day. But in one hour we spend a lot of money… per day it’s 4.20 euros. We don’t earn that here, no way… no way! [Irene, 65 years old, slavery, sentence of five years and six months, imprisoned for two years and 10 months].

Resonating with and corroborating previous studies (Gray, Rooney and Connolly, 2021; Garrihy, Marder and Gilheaney, 2022; Maculan, 2024; Maycock, 2022; Silva, 2020; Suhomlinova et al., 2022), it is, therefore, clear that the Covid-19 pandemic further exacerbated the depth of imprisonment (Crewe, 2021). Specifically, it intensified the degree of control, as movement and contact became even more restricted; the sense of isolation, both inside and outside prison, as social interactions decreased significantly, even during extremely psychologically difficult periods (such as the death of loved ones); and the difference from the outside world, as the unique conditions of prisons did not allow for the kind of isolation that occurred in most external contexts. In this sense, the relationship between the prison and the outside world was fundamentally reshaped, with serious consequences for those imprisoned. Moreover, despite the series of measures taken to mitigate this increased depth of imprisonment, such as the installation of telephones in cells, it ended up becoming a new vector of inequality within the prison context, as access is dependent on the availability of economic resources.

The use of masks as a kaleidoscope on diverging rationales

The aforementioned controversy over the use of masks in prisons is also evident in the interviewees’ narratives. Among participants who consider the use of masks useless within the prison environment, their justifications echo those articulated by representatives of DGRSP. As Leonardo describes, considering prison conditions, characterised by overcrowding, daily sharing of living spaces and the impossibility of maintaining social distancing (Fróis, 2020), masks do not serve the purpose of protecting against the spread of the virus.

We are talking about places where, sometimes, there are cells with 10 or 12 people. For these people it is not possible to maintain social distancing. Therefore, what we have to do is ensure that the virus does not enter there. From the moment they are there [in prison] they can be maskless. [Leonardo, NGO representative]

Nonetheless, some participants argue that despite prison conditions, the use of masks is a measure of paramount importance for public health. According to participants who advocate for such a position, it is a matter of ensuring equality:

If I am in favour of wearing masks outside, even more in prisons [laughs]. A prisoner who is infected during imprisonment has to be infected by State agents: either prison guards or officials. The prisoner is in confinement! Greater confinement than that cannot exist! So, he’s really in lockdown [laughs]. The prisoner is a citizen under the care of the State. You have to protect him; you cannot give him diseases. [Afonso, NGO representative]

Some interviewees argue that the mandatory use of masks in prisons was initially delayed due to its associated costs: “The problem is that there was no money for masks!” [Afonso, NGO representative]. Another justification cited by participants was the need to ensure surveillance and guarantee security in the prison environment, as the masks could hinder imprisoned individuals’ identification.

With the use of masks, it is more difficult to know who is who. […] With masks, it is more difficult to identify them. [Daniel, prison guard]

The controversies that permeated the management of the Covid-19 pandemic in prisons, therefore, expose longstanding contradictions within prison contexts (Fontes, 2022). Prisons are entangled in cumulative, overlapping and sometimes conflicting rationales that balance goals and practices ranging from the goal of humanising prison regimes to the brutal exercise of various forms of symbolic violence (Granja, 2019). As a result, the management of daily life in prison unfolds at the intersection of these contradictory regulatory principles. In this particular scenario, the Covid-19 pandemic, and in particular the decisions regarding the (non-)mandatory use of masks, serve as a kaleidoscope to reveal the divergent rationales that characterise the prison system and to highlight the tensions between an under-resourced context with poor living conditions, where security is an overarching principle, and the need to ensure the protection of imprisoned individuals as a matter of public health (Suhomlinova et al., 2022; Maculan, 2024).

The Law 9/2022 and the magnifying glass of pre-existing social problems

As explained above, Law 9/2020 introduced an emergency release scheme under the Covid-19 pandemic in the Portuguese prison system, thus enacting a decarceration strategy as suggested by the United Nations and the Council of Europe (Maruna, McNaull and O’Neill, 2022). Within the scope of this research, we sought to understand the viewpoints of the interviewees on the outcomes of such a policy. According to the majority of those interviewed, this Law and its provisions were generally viewed as positive because they allowed controlling prison overcrowding during a particularly challenging period, thereby preventing the rapid and potentially uncontrollable spread of infection. However, the myriad of challenges arising from a very quick adoption of early release schemes without any kind of preparation (Fróis, 2020) were also described by interviewees, particularly professionals:

I think [the Law 9/2020] is fine. But not in the way it was done, because many of them [imprisoned individuals] left with no backup and they were not prepared nor did they have a family structure or institutional structure to support them. And some cases were even a little dramatic because they had nowhere else to go and [their release] has not been streamlined with entities that work in this area. On the one hand, it’s good because those who had support easily managed to have assistance; for those who didn’t, there were some more complex and unpleasant situations […] because that was a little overnight. [Alice, NGO member]

The early release of imprisoned individuals during the pandemic, therefore, served as a magnifying glass of the long-standing and profound difficulties entailed in reentry (in this respect see, Gomes and Rocker, 2024). The Portuguese Ombudsman in the Justice field, Maria Lúcia Amaral, pointed out, more than a year after the approval of Law 9/2020, that the imprisoned individuals released in April 2020 were not adequately supported, leading to many becoming homeless (Faria, 2021). Similar challenges were also recognised by prison guards who accompanied such processes and described how several individuals returned to prison:

We already have individuals here who left and who have already returned. They were covered by these norms and have already entered again. […] That’s why I say: the base is poorly made. That is, you set a person free and do not think. […] And as a rule, this gives a bad result, when things are not thought through. [Lucas, prison guard]

Overall, the professionals interviewed believe that the main reason for people returning to prison is the lack of preparation of the early release programme. According to their narratives, for some families, imprisoned individuals unplanned and unexpected returns posed an additional burden, particularly challenging to manage during a period compounded by the lockdowns. This position is explained by an NGO member and a prison guard:

Most of the prisoners are poor people and having another person at home, who cannot go out - the 45 days are meant to be spent at home - he cannot go to work… It´s just another mouth that the family has to feed! [Samuel, NGO member].

I mean, they’re deprived of their freedom in here, they’re going to leave to stay at home. […] Then it’s another mouth to eat, families are already experiencing difficulties… And we had some cases where that had to return [to prison], and others that we went to look for, because either they had breached conditions, or they really couldn’t afford it. [Luísa, prison guard]

In addition to vulnerable family conditions to accommodate individuals on early-release schemes, some interviewees also outlined the failed expectations regarding release in a pandemic context characterised by several movement restrictions, as outlined by a prison guard:

If you ask me “Were they prepared for leaving prison in this phase of Covid?” No, nobody is. They are not prepared for a reentry with the normal national panorama, even worse in this scenario. The possibility of them having professional activities at this time? Zero. Possibility for them to do what they yearn for when they are free, which is to go for a walk, see the beach, see the mountains, go to a restaurant, go to a bar, go to a disco… In other words, there is a contradiction here of drives and intentions […]. Because things can go well, but they can go very badly. Either she [prisoner] has a lot of self-control and has support, a financial backup, or else she cannot survive this phase. [Marta, prison guard]

Despite the challenges associated with the implementation of such an emergency release scheme, some interviewees point out that the management of the Covid-19 pandemic still prompts a profound discussion about the penal system, a position also outlined by scholars in the field (Maruna, McNaull and O’Neill, 2022). One NGO member points out that the reduced recidivism rates following Law 9/2020 clearly demonstrate the importance of pursuing alternatives to imprisonment beyond the exceptional circumstances of Covid-19.

I think this law proves that there are a lot of people in our prisons who shouldn’t be there. Maybe even some that should never have gone there. The increase in crime that was talked about, or that some political poles like to ride these waves of fear are not true! In fact, the recidivism of these people was very low. After six months it had been 1%. That’s like saying zero recidivism rates. So, it’s a success. I hope that we can learn from this that we can create alternatives here at the end of sentences, to also reduce the weight that prison has and the weight that this has, for us, the state, for our taxes since it is expensive to keep these people in prisons. [Leonardo, NGO member]

Law 9/2022 established a decarceration strategy with both operational and humanitarian objectives. However, given the urgency of the situation, the timeframe of the process was so rapid that individuals were released without addressing structural inequalities, many of which were exacerbated by the pandemic situation: a lack of socio-economic activity conducive to obtaining employment, strangled social security services and overburdened health systems (Fróis, 2020; Maruna, McNaull and O’Neill, 2022). Law 9/2022 has therefore acted as a magnifying glass, exacerbating pre-existing social problems faced by prisoners upon reentry (Gomes and Rocker, 2024). Nonetheless, this extraordinary measure also suggests that further consideration needs to be given to early release schemes and the implementation of alternatives to incarceration that are genuinely capable2 of relieving pressure not only on prisons but on the penal system as a whole (Davis, 2022). As posed by Maruna and colleagues (2022: 1), “If a deadly pandemic is not enough to instigate a reimagining of the role of prison in society, it is unclear what could”.

Conclusion

Although 2023 marked the year in which the World Health Organization declared the end of the Covid-19 pandemic, the profound implications of such an exceptional moment continue to unfold across various spheres of society. This is particularly relevant in prison, as these contexts became even more opaque during a period when the rights of imprisoned individuals were more at risk. This article aimed to contribute to expand and consolidate such reflection by exploring the implications of the Covid-19 pandemic in the Portuguese prison system through the perspective of imprisoned individuals aged 65 or over and professionals.

Our data shows that besides severely disrupting the daily routines of imprisoned individuals, Covid-19-related restrictions were particularly pernicious for the preservation of social ties, with implications that extended well beyond the resumption of prison visits. Given the critical importance of these bonds for the mental health of imprisoned individuals (Granja, 2017), as well as to their re-entry process (Gomes and Rocker, 2024), it is of utmost relevance to further investigate the long-term implications of visitation interruptions during the lockdown, as well as its limitations afterwards. The institutional management of the pandemic in prisons, which entailed, among other issues, controversial decisions about the use of masks in prison contexts, also exposes long-standing paradoxes within prison contexts as contradictory principles collide. Such results illustrate how, during times of uncertainty, the structural principles and inherent problems of the prison system, along with associated tensions, tend to leave imprisoned individuals in even more vulnerable positions (Maculan, 2024). Finally, the adoption of Law 9/2020, facilitating the release of approximately 2000 prisoners from the Portuguese prison system, underscores how unprepared releases can exacerbate imprisoned individuals’ social, material, and economic vulnerabilities.

The overarching project on which this article is based focused on ageing in prison. However, other vulnerable groups, such as imprisoned individuals with health problems/chronic illnesses and disabilities, also deserve special attention. Our analysis therefore highlights the critical importance of investigating the long-term effects of post-Covid-19 restrictions, paying particular attention to how these effects might vary according to gender, age, nationality and other social position categories.

Funding

This work has been funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT - Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology) under the Programme Scientific Employment Stimulus - Institutional Call, attributed to Rafaela Granja (https://doi.org/10.54499/CEECINST/00157/2018/CP1643/CT0003), as well as under the Restart Programme for the research project “Electronic monitoring in the criminal justice system: projected futures and lived experiences” (2023.00030.RESTART). In addition, this work is supported by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, IP, under the project UIDB/00736/2020 (base funding) and UIDP/00736/2020 (programme funding).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to the individuals who kindly agreed to be interviewed for this study. Their invaluable insights and cooperation were essential, and without their participation this research would not have been possible. We are also deeply grateful to the General Directorate of Prisons and Social Reintegration (DGRSP) for allowing us to conduct this study under unforeseen and challenging circumstances. Finally, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to the reviewers, whose constructive feedback and thoughtful suggestions have greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.