Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Etnográfica

versión impresa ISSN 0873-6561

Etnográfica vol.21 no.3 Lisboa oct. 2017

ARTIGOS

Crafting a doll and a film: challenges in filming a doll-in-the-making

Fazer uma boneca e um filme: desafios em filmar uma boneca-sendo-feita

Inês PonteI

IInstituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa (ICS-ULisboa), Portugal. E-mail: ineslponte@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This article looks into Making a Living in the Dry Season, a research film grounded in a long-term stay at a highland agro-pastoralist village in Namibe province, Angola. The film is an intimate portrait of the day-to-day life of a family examining through the practice of doll-making a twofold notion of labour, that is, the labour in crafting and the labour in making a living. I explore insights acquired by the process of making this film and its relation with the end result, discussing the challenges of using filmmaking as a research method, and as an outcome into a film. I look at the knowledge generated in filming, and its subsequent editing and re-editing, paying attention to the role of differing partnerships in the overall production process and in shaping the finished film.

Keywords: visual anthropology, filmmaking, materiality, ethnography, Angola

RESUMO

Este artigo explora o filme Fazer pela Vida na Estação Seca, baseado em trabalho de campo prolongado numa aldeia agropastoril de montanha localizada na província do Namibe, em Angola. O filme é um retrato íntimo do quotidiano de uma família e explora, através da feitura de uma boneca, uma noção dupla de labor, isto é, o trabalho artesanal e o fazer pela vida. Neste artigo investigo o conhecimento adquirido pelo processo de fazer este filme e a sua relação com o produto final, discutindo os desafios de usar produção cinematográfica enquanto método de pesquisa e enquanto resultado na forma de filme. Exploro o conhecimento gerado no processo de filmagem e sua posterior montagem e remontagem, sublinhando o papel de diferentes parcerias no processo da sua produção e suas implicações no desenho do filme acabado.

Palavras-chave: antropologia visual, filme etnográfico, cultura material, Angola, etnografia

Introduction

It was a relief when Madukilaxi started crafting the doll I had asked her for some time back, because I could then film the whole process.[1] Having lived on a farm in a highland village in Angola for about six months, I had been waiting about a month to get my host to craft a doll for my research project – she kept delaying while saying she would do it. Finally, when she started crafting it, she was explicit about the reason for her delay. Ondjila nondjala, no djitunga ovana vaInes!, Madukilaxi told me on camera. Having learned Olunyaneka, the bantu language my host spoke, only since my arrival, I eventually understood her comment as meaning [Dry seasons] hunger is coming and Im making a doll for Ines! This comment might make my request appear quite dubious yet it also shows how this doll-in-the-making was a vehicle to understand the social value of such a craft in my rural fieldsite. Madukilaxis comment also opened up the challenge of making an ethnographic film about this handcraft that positioned some of its social conditions, rather than aiming to show the whole doll-making process in the vein of practices of scientific ethnographic film dealing with material culture and technical processes as documentation (Henley 2000a).

This article looks into Making a Living in the Dry Season, a research film made for my PhD in Social Anthropology with Visual Media at the University of Manchester, United Kingdom.[2] I explore insights brought by the making of this film and its relation with the end result, discussing challenges of using filmmaking as a research method, and as an outcome into a film. I look at it as a film-in-the-making, exploring the knowledge generated in filming, and in later editing and re-editing, paying attention to the role of differing partnerships in shaping the finished film. I also locate it in relation to previous films about rural populations in Southwest Angola, outlining an account of cinematic genres involving documentary and fiction film productions with shorter periods of filming.

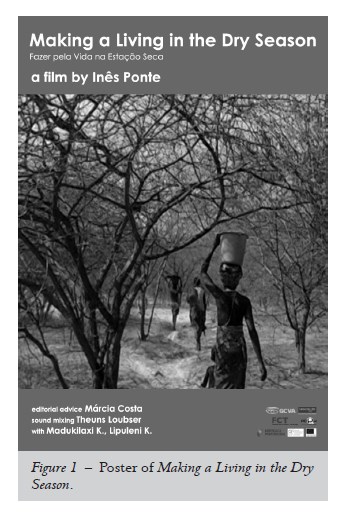

Making a Living is grounded in a long-term stay in Katuwo, a highland agro-pastoralist village in Namibe province.[3] Through my request to Madukilaxi to make me a doll, the film examines a twofold notion of labour, consisting of the labour in crafting and the labour in making a living. In this intimate portrait of the day-to-day life of a family, Lipuleni, Madukilaxis toddler, also follows our twofold labour, and the three of us finally celebrate our efforts with a feast (fig. 1).

It certainly complicates things that a film about handcrafting is combined with locating the livelihood of the filmed participants. Yet this outcome converges the filmed participants agenda with my own in several instances. Half way through my stay in the village I suggested to my hosts the making of a film, a suggestion which was well received. Overlapping with my research agenda on doll-making, my host couple wanted to show their lifestyle and their accomplishments. For the film, I commissioned Madukilaxi to make a doll during the dry season, without realising how out of season my request was, a process that eventually revealed me the role of making a living in its crafting on the one hand, and the significance of the social relationships established on the other. In editing I attempted to incorporate our dual agenda in the film, finding that only by reflecting in the film on my overall role, I could make cinematic justice to the ethnographic narrative I wanted to convey.

At the time of submission I had many things to show and tell through the film: I had accomplished a 63-minute version as the outcome of using filmmaking as a research method for my project.[4] About a year after finishing my degree, I contacted a professional editor to get her editorial advice on the film, turning Making a Living into a 35-minute version, aimed at a broader audience. Though the length of the film changed, I kept the same narrative aim, and thus the same synopsis fits both versions well.

I used in the overall project an assemblage of methodological tools, with an emphasis on visual methods that included filmmaking and photography, progressively looking at the assemblage as having the prominent shape of making as method. This implies relying not only on participant-observation, but also on engaging in many activities that had making at their centre. Filming a commissioned doll-in-the-making was one of those activities; making a film about it was another. From a practice-related research perspective, this combines both practice-led and practice-based research (Candy 2006) in the way that both the making of a doll and of a film converged in embodying new knowledge about the doll-in-the-making and about film-as-research method. Focusing on making as an insightful process to better understand the social significance of things in situated contexts (Ingold 2007), in the film I aimed to establish a triangular discussion of a hand-crafting activity – doll-making –, the rural making a living of the filmed participants, and my filmmaking, whereby I analytically merge okutunga (handcrafting) with ovilinga (labour) in a reflexive way.

The increasing concern in anthropology that material culture relates to the understanding of the social relations people establish through and with particular things has introduced a term currently in use in the discipline: materiality. Anthropologist Tim Ingold (2010) has regretted how often the heterogeneous research carried out under the term materiality has consisted of debates that transcend the material qualities of things, and has called for attention to things-in-the-making rather than on things already made as a way to emphasise peoples engagements with things. In this research, I find a balance between engaging with both things-in-the-making and things already made quite enriching. For the film, I was somewhat able to combine looking at how people engaged with an already made doll and with a doll-in-the-making – besides the commissioned doll, my host had made a doll about ten years before that was still stored on one of their farms. During my research the film was also a thing-in-the-making, yet to provide research context to this film, and to introduce my general concerns with using filmmaking in this research, I first locate the produced film among some of the existing film productions on rural Southwest Angola.

Previous films on rural Southwest Angola

Using the documentary genre, I aimed at exploring the narrative grounded from an intimate and relational perspective on the film characters day-to-day life combined with the doll-making at my request. Before my fieldwork, I was concerned not only with enabling doll-makers voices through film, but also their body – that is, a whole person, for which I later found the expression corporeal voice.

There are not many films made about rural populations in Southwest Angola, but the few existing ones include some remarkable examples in which the filmed subjects have a certain voice.[5] That is the case of the work of filmmaker and later anthropologist Ruy Duarte de Carvalho (1941-2010), born Portuguese and naturalised Angolan after the countrys independence in 1975. Carvalhos films explore the lived reality of people in rural Southwest Angola within the broader frame of Angola as a recently independent nation (Moorman 2001) but they are also different filmic experiments in providing access to indigenous voices.

Contemporary Angola/Time of the Mumuilas (CATM) is a television documentary series of ten episodes about the agro-pastoralist Ovamwila (Ovanyaneka ethno-linguistic group), in the Angolan post-independence context (1975).[6] People speak in all of the episodes, yet a voice-over translates the speech of the rural dwellers into Portuguese. Following a different approach, the later ethno-fiction Nelisita (1982a) Carvalho directed was produced with Ovamwila people as well and was inspired by Ovanyaneka oral narratives.[7] Portraying locals telling their own stories, the short voice-over of Nelisita and peoples direct speech are in Olunyaneka, subtitled in Portuguese.[8]

Coming from a background in cinema, Carvalhos writings on ethnographic film include discussions on the eventual discomfort between ethnography and cinema (see Carvalho 1984, 1986, 1991). Significantly, Carvalhos sense of the necessary delicate zone of commitment (1984: 14) between filmmaker and filmed participants for the ethnographic film stands in the realm of negotiating discourses and translated voices. Carvalho looks at his cinema as political – a cinema of urgency (1984: 12), not as ethnographic film.

From an historical perspective, the sense of Carvalhos cinema of urgency locates different political dimensions than what is often used to describe films made under the idea of a salvage anthropology. This is the case, for instance, of the British sisters Diana and Antoinette Powell-Cottons earlier films, which contemplated registers of technical processes among the Ovambo, such as Kwanyama Potters Methods (1937). Associated with a technological change such as sound recording, one of Carvalhos CATM episodes, Occupations, depicts four specialised crafts relevant in local terms – pottery, hairdressing, healing, and blacksmithing – thus providing the viewer with indigenous voices about each technical process approached in the episode, translated through a voice-over in Portuguese.[9]

Carvalhos experiments in providing access to indigenous voices are perhaps better situated in contrast with a previous production, Esplendor Selvagem [Wild Splendour], a documentary directed by António Sousa in Angola pre-independence (1972). Resulting from unusual access, this film might be better seen as interesting evidence of dances and customs of various rural Southern populations at the time of its distribution.[10] However, the external narrative told by the voice-over in Portuguese provides little space for the corporeal voice of the filmed subjects except as objects of folklore belonging to the seasonally changing landscapes populated by wild animals. Effacing that voiced narration would turn the film into a record without much of a standalone understanding for the viewer who is unfamiliar with the filmed cultural context.

It is in this context and inspired by Carvalhos approaches that the core of Making a Living in the Dry Season as an ethnographic film consists of a reflection on making in which I aimed to give a corporeal voice to the filmed participants, which was rooted also in an awareness of the contemporaneity of our filmic encounter. As very little was known about the way in which makers relate (and related) to dolls they handcraft, corporeal voice came to me through thinking about ways of moving beyond the issue of their silenced voice or translated discourses.

An earlier definition of scientific films, of which ethnographic ones are taken as a type, is based on considering the camera as able to record an objective reality – approach promoted, for instance, by the German IWF (Fuchs 1988; but see also the debate between Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead in Bateson, Mead and Brand 1976). Rejecting this earlier positivistic perspective based on its realistic character, well established practices of visual anthropology have been exploring film not only as a certain type of evidence or record, but also by considering its expressive qualities as a conceptual medium to communicate descriptively and analytically cultural relations (e. g. MacDougall 1997; Henley 2000b). Making a Living is grounded in constructing a certain ethnographic narrative and thereby a representation of particular social relationships involving all people related to the films production: the filmed participants and the filmmaker. While focusing on daily activities, the film simultaneously portrays relations: it relies extensively on the relationships I established during my fieldwork in the village. Making this film became a mutual engagement, not only in the filming itself but also in the crafting of the commissioned doll. I now turn to discussing the findings filmmaking provided in relation to a doll-in-the-making.

Filming and making

Filmmaking grounded access to particular subjectivities of people in relation to artefacts-in-the-making in the context of my research, but not all insights I gained through using this method in the field appear in the final product. For instance, a scene in which Djambelua, Madukilaxis sister-in-law and our neighbour, weaves a basket showed me how a certain kind of filming could in fact work against my openness to things-in-the-making. One day, when visiting Djambelua on my way to film an overview of the village from the top, I saw her working on a basket-in-the-making, and I thought to take advantage of that event to get her tell the camera what artefact she was making. The ensuing dialogue between her and me as a behind-the-camera filmmaker strikes me for my intriguing dissatisfaction with Djambeluas answer to my somewhat clumsy questioning Ulingatchi? Ko maoko yove?, attempting to ask her what is this in your hands? as a way to get a voiced reply from her. For Djambelua, she is making (okutunga), while me, I am focused on getting her tell me what she is making, a big basket (ombue). The scene encapsulates a differing attention given to the artefact as an unfinished product and to the process of its craft in the context of my fieldwork setting. Grounding the film on Madukilaxi soon made this scene disappear from the 63-minute version.

Filming other things-in-the-making such as a basket allowed me to observe the attention paid to skilful crafting in the village, but for the film I chose only to combine personal taste and practical decisions involved in the doll-in-the-making. I was filming when Madukilaxi decided to redress the commissioned doll with a big skirt and, surprised to see this change, I asked her to dress the doll in similar clothing to that of the children again, an omundondi at the rear and an oxitati in the front.[11] My request surprised Madukilaxi, who considered it strange to see me wanting to dress the doll I would take home with a fabric in the same pattern as the one I was using to cover my head. It was a contrasting evaluation of aesthetics. Though this was the only negotiation of style about the doll-in-the-making between us, not all of her decisions and choices are or might be explicit in the film. For instance, I had brought a colourful mixture of two different sizes of beads for her to choose from. She decided to use the bigger beads for the doll, keeping the smaller ones to make both a necklace and a multi-layered beaded belt for herself. The bigger beads were much easier to handle, and thus faster to thread, and she considered the smaller beads more beautiful.[12] Ten years ago Madukilaxi had made a similar choice, to use big beads, for the doll she had made for her eldest daughter – such doll was the reason I asked Madukilaxi to make me one. In contrast to that doll, for the doll I commissioned she added her own stored hair to compose its beaded hairdressing on top.

Filming this doll-in-the-making helped me to understand social values around this practice, and I found that the implications of my commission at an unfavourable time should be made clear in the film. My filmed participants agenda of showing their lifestyle resonated strongly with that purpose. I now turn to discuss how in editing I tried to compose an ethnographic narrative that converged these agendas into the insight I had gained about doll-making and its relationship with peoples preoccupation with making a living.

Making and remaking a film about making

Aiming to provide a corporeal voice to my protagonists, I had planned to film what later became Making a Living through a cinematic form essentially similar to the observational approach looking at a particular case of doll-making within the day-to-day life of an agro-pastoralist household dwelling in a highland village. Even so, Making a Living turned out to be an experiment that goes beyond what is known as classical observational cinema, as I took advantage of the capacity of all stages of the filmmaking process to enable new knowledge to develop (Henley 2000b). It was only while I was editing the film that I decided to explicitly explore the encounter between my hosts and me, as a way of providing insights into the particular everyday context that related to the doll-making within the contemporary time of our encounter on their farmstead. In the footage I looked for ways in which to strengthen the role of a triangle of characters consisting of Madukilaxi, her toddler Lipuleni, and me, as a behind-the-camera person.

Filming ended having a participative dimension with the protagonists; yet the director multiplied into several roles, from production to cinematography and sound recording, from editing to post-production. In contrast with Carvalhos cinematic productions, I followed the Granada Centre style in the way that both filming and editing consisted of the work of one person only.[13] According as well with the opportunities offered by the GCVA, at different stages of the editing process I asked and received many different suggestions from my supervisors, peers and staff. Over a year, I reached for the submitted version by preparing three work-in-progress versions to present at the Filmwork for Fieldwork Seminars, and by getting feedback from audiences made up of both visual and social anthropology students and lecturers. Their feedback was important to understand what kind of message the assembled material proposed and to develop the cut further, and complemented individual sessions.[14] Through screening evolving cuts I was able to measure how much the idea of making a living was there; or to realise how my topic centrally engaged with the womens world – and work –, in a way that could wrongly promote the idea that men do not work as much as women in that rural African context (see Whitehead 1999, for a similar perception in the case of rural Zambia). As guiding as those discussions were, at that point the film was not my priority. The filmed material helped me in the writing of the thesis, the submitted film made my point about doll-making and its interrelationship with making a living; the final product for a general audience could wait.

A short remaking period followed the long path of making this film. In early 2016, I decided to approach a professional editor specialised in documentary with my 63-minute cut, suggesting for her to give me her editorial advice on it. Engaging with the material using her training and professional experience – what Cristina Grasseni (2007) calls skilled vision –, she proposed changing the films pace and its narrative balance. She concomitantly evaluated some of the materials ability in passing its intended message to a general audience. Some of the issues she raised were possible to solve through changes in subtitling. She mentioned the problem, for instance, of the double naming of Lipuleni, whom her mother calls a different name, without further explanation possible in my footage. She was also unconvinced about how subtitles assumed what the images did not show in scenes in which either Djambelua or me spoke as carers of Lipuleni: a usual practice in minding small children is to share the task with other women. Having explained to her the ethnographic narrative I had aimed for, the editor worked on focusing material providing hints into several specific social practices in the village, to pass only the main narrative rather than adding another layer of meaning (cf. Henley 2000a: 216, discussing the contrasting nature between writing as an expansion of fieldnotes and editing as a synthesis). She showed me scene by scene how that just compromised the already complex narrative I wished to present in the film. Working together, she ended up proposing a 35-minute version, and her name as an editing advisor: she had helped in reshaping a film; she had not made one from the whole footage.

Making a living, the notion of the labour involved in the day-to-day life, was one of the significant findings that filming the doll-in-the-making had shown me. However, I was not able to measure how much I was subjugating my approach to doll-making in the film to such research findings. My editing partnership challenged this choice, as the editors suggestion was to link these two dimensions, doll-making and making a living, in a more subtle and harmonious way, pushing doll-making also into the first part of the film. The effect was to empower the message I aimed for the film to carry.

Conclusion

Oh me atxo! Oh méyo! Oh méyo[, oh Ines!/ I see myself, I see my mum, I see my mum[, I see Ines!] [Lipuleni, looking through the camera lens].

The editor I worked with reshaped the opening scene of the 63-minute cut, in which two-year-old Lipuleni looks through the lens of my film camera. Looking at the reflection, she describes what she sees: I see myself, I see my mum – she continues guiding us through what she sees. In the cut, after recognising herself and her mum in the reflection, Lipuleni followed to recognise me behind the camera. My editor commented how that was obvious throughout the whole film, and as such that part was not needed. Her point made me think how both making and reflexivity are significant dimensions in the film without all the explicit material I had regarding those dimensions.

I used filmmaking as a tool to grasp the corporeal voice of a person who carries out doll-making within her everyday life, grounded in the concrete and particular nature of film (Henley 2000b: 50). It was its ability to meaningfully express the everyday life concerns of particular people which first interested me for this research purpose. When I asked Madukilaxi for a handcrafted doll, filming a doll-in-the-making became a social interaction device that created unexpected knowledge about the socio-cultural reality of people who make dolls in Southwest Angola. Besides the possibility of attending to the skills and strategies involved in doll-making, it made me attentive to my hosts making a living. It made me aim at collecting filmed material through which I could develop a plot engaged with a doll-in-the-making and the making a living of the film participants. Following seriously what my research collaborators had showed, in the editing process I attempted to weave these dimensions into an ethnographic plot. Yet, engaging with a film editor showed me how I took those insights too seriously for cinematic purposes and she balanced it back. Re-editing helped to shape the film into the ethnographic narrative that could reflect the insights gained by fieldwork and filmmaking.

According to MacDougalls discussion on ethnographic film (1994), when filming embodies an element of surprise, it might generate more complex statements. For this film, which combines participatory and observational cinema, this embodiment was fabricated both in its process (of filming), and in its product (after editing). I challenged myself to look at the filmed material and to find an ethnographic narrative from it that made justice to my field experience of commissioning a doll and learning about the role of making a living in it for my hosts. I later approached an editor to understand what her skilled vision illuminated in the ethnographic plot I had designed in the 63-minute version. I let understandings arise by filming and editing, to take me by surprise and remain open to the process of re-editing.

Filming and turning it into a filmmaking product took place under different collaborative contexts. While for the submitted cut the input of the film participants was central, for the re-edited film I was working together with someone who was distant from my field experience but also from my anthropological concerns – someone who was not expecting to be overwhelmed by too much information to appreciate it. For my editor partner I was negotiating the ability to make a standalone film. For me, I was negotiating the balance between a research method and a research output. Constrained by self-production methods, from the definition of the concept over 2010 and 2011, shooting in 2012, and editing over 2013 to 2016, eventually this short documentary was made with significant contributions – I have underlined how the protagonists showed me what to aim for, and how the editors assistance helped to shape that content. Self-distribution of the 35-minute film has, up to now, lead it to circulate both in academic screenings and in ethnographic and world cinema film festivals, mostly through the eastern part of Europe (Greece, Estonia, Slovenia, Macedonia, Croatia, Hungary), with a premiere in Portugal in August 2016 – partly fulfilling Madukilaxis expectations that through film I would be able to show their accomplishments all over the world. I still wonder how my filmed participants and hosts would perceive the balance I found in negotiating the narrative. Not wanting to take the future for granted, I might be able to find out their view soon when a return to this rural fieldsite for further research takes place.

REFERENCES

BATESON, Gregory, Margaret MEAD, and Stewart BRAND, 1976, For Gods sake, Margaret! Conversation with Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, CoEvolutionary Quarterly, 10: 32-44. [ Links ]

CANDY, Linda, 2006, Practice Based Research: A Guide. Sidney, University of Technology, available at < https://www.creativityandcognition.com/resources/PBR%20Guide-1.1-2006.pdf > (last access October 2017). [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Ruy Duarte de, 1984, O Camarada e a Câmara: Cinema e Antropologia para Além do Cinema Etnográfico. Luanda, INALD. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Ruy Duarte de, 1986, Audiovisual e antropologia: quatro fragmentos inconfortáveis, in Ruy Duarte de Carvalho, Ana a Manda: Os Filhos da Rede. Lisbon, IICT, 330-333. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Ruy Duarte de, 1991, An Angolan view of the 1990 RAI Film Festival, Anthropology Today, 7: 19-20. [ Links ]

CASTELO, Cláudia, 2014, À conversa com Benjamim Pereira: memórias do Centro de Estudos de Antropologia Cultural e do Museu de Etnologia, in Clara Saraiva, Jean-Yves Durand and João Alpuim Botelho (eds.), Livro de Homenagem a Benjamim Pereira. Viana do Castelo, Câmara Municipal de Viana do Castelo, 233-241. [ Links ]

CASTRO, Teresa, 2013, Viagem a Angola: cinema científico e etnográfico, in M. C. Piçarra and J. António (eds.), Angola: O Nascimento de Uma Nação, vol. 1: O Cinema do Império. Lisbon: Guerra e Paz, 123-157. [ Links ]

COSTA, Paulo Ferreira da, Cláudia Jorge FREIRE, and Benjamim PEREIRA, 2010, Entrevista a Benjamim Pereira: Uma aventura prodigiosa , Etnográfica, 14 (1): 165-176. [ Links ]

ESTERMANN, Carlos, and António SILVA, 1971, Cinquenta Contos Bantos do Sudoeste de Angola: Texto Bilingue com Introdução e Comentário. Luanda, IICA. [ Links ]

FLORES, Carlos, 2009, Reflections of an ethnographic filmmaker-maker: an interview with Paul Henley, director of the Granada Centre for Visual Anthropology, University of Manchester, American Anthropologist, 111: 93-99. [ Links ]

FUCHS, Peter, 1988, Ethnographic film in Germany: an introduction, Visual Anthropology, 1 (3): 217-233. [ Links ]

GRASSENI, Cristina, 2007, Skilled Visions: Between Apprenticeship and Standards. New York, Oxford, Berghahn Books. [ Links ]

HENLEY, Paul, 2000a, Ethnographic film: technology, practice and anthropological theory, Visual Anthropology, 13 (2): 207-226. [ Links ]

HENLEY, Paul, 2000b, Film-making and ethnographic research, in Jon Prosser (ed.), Image-Based Research: A Sourcebook for Qualitative Researchers. London, Routledge, 42-59. [ Links ]

INGOLD, Tim, 2007, Materials against materiality, Archaeological Dialogues, 14: 1-1. [ Links ]

INGOLD, Tim, 2010, The textility of making, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 34 (1): 91-102. [ Links ]

LANÇA, Marta, 2015, Nelisita e o cinema etnográfico, Rede Angola, available at < www.redeangola.info/especiais/nelisita-e-o-cinema-etnografico/ > (last access October 2017). [ Links ]

MacDOUGALL, David, 1994, Whose story is it?, in Lucien Taylor (ed.), Visualizing Theory: Selected Essays from V.A.R., 1990-1994. New York, London, Routledge, 27-36. [ Links ]

MacDOUGALL, David, 1997, The visual in Anthropology, in Marcus Banks and Howard Morphy (eds.), Rethinking Visual Anthropology. New Haven, Yale University Press, 276-295. [ Links ]

MOORMAN, Marissa, 2001, Of westerns, women, and war: re-situating Angolan cinema and the nation, Research in African Literatures, 32: 103-122. [ Links ]

WHITEHEAD, Ann, 1999, Lazy men, time-use, and rural development in Zambia, Gender and Development, 7 (3): 49-61. [ Links ]

FILMOGRAPHY

ALMEIDA, António de, 1952, Entre os Bosquímanos de Angola, 28 min., Instituto de Investigação Científica e Tropical, Portugal.

BORLE, Marcel, 1929, Voyage en Angola, 16 mm, B&W, 60 min., Production Borle, Switzerland.

CARVALHO, Ruy Duarte de, 1979, Presente Angolano / Tempo Mumuila, 10 episodes, B&W and colour, 16 mm, Televisão Popular de Angola, available at < www.vimeo.com/channels/presenteangolano > (last access October 2017).

CARVALHO, Ruy Duarte de, 1982a, Nelisita: Narrativas Nianeka, B&W, 16 mm, 65 min., Instituto de Cinema Angolano, available at < https://vimeo.com/154832740 > (last access October 2017).

CARVALHO, Ruy Duarte de, 1982b, O Balanço do Tempo na Cena de Angola, colour, 16 mm, 44 min., Instituto Angolano de Cinema, available at < https://vimeo.com/158312633 > (last access October 2017).

PONTE, Inês, 2016, Making a Living in the Dry Season, 35 min., Granada Centre for Visual Anthropology.

POWELL-COTTON, Diana, and Antoniette POWELL-COTTON, 1937, Kwanyama Potters Methods, 16 mm.

SOUSA, António, 1972, Esplendor Selvagem, colour, 35 mm, 90 min., Astória Filmes.

NOTES

[1] This article is based on the PhD research Crafted children: an ethnography on making and collecting dolls in Southwest Angola. Research was funded through the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal) doctoral grant SFRH / BD / 69805 / 2010. The writing of this article was carried out with the support of a post-doctoral Marie Curie Fellowship (747508), financed by the European Commission, and its revision by a FCT post-doctoral grant SFRH / BPD / 115706 / 2016, both at ICS-ULisboa. I thank the participants attending the 2017 CRIA Seminar at ISCTE-IUL, where I presented a previous version of this paper, their feedback, in particular to Antónia Lima. I also thank Ricardo Roque for very helpful suggestions, as well as the anonymous reviewer for Etnográfica, and Gloria Dominguez for her fast and attentive feedback.

[2] For the trailer, by Márcia Costa, see www.vimeo.com/242457828 (last access October 2017).

[3] The village is located in a semi-arid region that has a short rainy season with irregular raining and a long dry season with regular shortage of food supply. It has known cycles of heavy rainfall with accompanying floods, intercalated with years of heavy drought.

[4] My interest in filmmaking, in particular in documentary, lead me to the PhD programme linked to the Granada Centre for Visual Anthropology (GCVA), a well-known school in this field (Flores 2009), where students can submit both a thesis and an audiovisual production, for which they are able to attend limited filmmaking training giving them the chance to make exercise-films under specialised tutorship; have access to a related film library; and to present and attend seminars about visual research work. I enrolled in the programme in September 2010, filming took place in 2012, editing since 2013 and I finished my degree in June 2015. A further re-editing period took place in 2016. Using a Panasonic DVX100, MiniDV, I shot in 4:3 letterbox, aiming at a resemblance with the 16:9 cinematic format. My overall footage is about 17 hours in total.

[5] Though there is a limited amount of films, it is a complex history to draw upon. Teresa Castro (2013) discusses the full range of films produced in Angola since the late 1920s up to the 1980s, looking at productions that paved within ideas of science and ethnography, some of which were made in the Southwest region and engaged with local populations. Besides the ones I discuss below, these include the travelogue Voyage en Angola (1929), by the Swiss Marcel Borle; and the Portuguese António de Almeidas films about the Khoisan, in the 1950s. I move quite ahead in time to point out that recently, Filmes Sem Futuro emerged in Lubango – a short fiction production company working with local theatre companies, whose films have recently circulated in film festivals worldwide.

[6] Titles translation of Carvalho (1979) taken from the British Film Institute (see http://www.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2b75b78e4c, last access October 2017). Each episode has between 20 and 60 minutes, all together running for about six hours (see www.vimeo.com/channels/presenteangolano, last access October 2017). Since February 2016 some episodes are accessible online at RDC Virtual, a Ruy Duarte de Carvalho digital film archive available at www.vimeo.com/rdcvirtual (last access October 2017).

[7] The script was based on the versions of António Tyikwa and Valentin fixated by missionaries Carlos Estermann, ethnographer, and António Silva, linguist (Estermann and Silva 1971). For more on the production conditions of this film, see Carvalho (1984) and Lança (2015); for the film, see www.vimeo.com/154832740 (last access October 2017).

[8] The 45-minute documentary Carvalho finished the same year, 1982, The Balance of Time in the Angolan Scene (Carvalho 1982b, my translation from Portuguese), combines both styles, a voice-over leading the narrative, and subtitles for direct speech in different local languages.

[9] See Ofícios, B&W, 16 mm, 29 min, Documentary, TPA (available at www.vimeo.com/154077837, last access October 2017). It would be interesting to compare Carvalhos CATM series with the films produced in the Portuguese rural context by the Institut for Scientific Film (Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film, IWF) in Gottingen, Germany, with the assistance of Benjamim Pereira and Ernesto Veiga de Oliveira for the Centro de Estudos de Antropologia Cultural / Museu de Etnologia do Ultramar in the early 1970s (Castelo 2014), as Pereira and Oliveiras work is also linked to a sense of urgency in the vein of salvage anthropology (cf. Costa, Freire and Pereira 2010: 168).

[10] For the attentive viewer, in this 90-minute film there are a couple of scenes showing young Ovakwanyama girls using dolls during their puberty celebrations, and an Ovamwila little girl attending other girls puberty celebration with her doll.

[11] In rural Angola, as in many other rural parts of contemporary Africa, waxed printed fabrics, bought in a standard size of 1.5 m × 1 m, are commonly used as everyday dressing. In Katuwo, as a whole piece or in parts for dressing and covering children and adults (and as womens headdress), standard fabric also has a multiplicity of other uses such as to pack and carry cargo.

[12] I emphasise personal taste here because Djambelua told me once how she considered the bigger beads more beautiful to make her belts with. The size of the beads for necklaces is related to a person having living or deceased parents.

[13] Though Carvalho used small teams by cinematic standards, they were larger than the one used by Sousa, yet both production strategies involve more people than the one for a project as Making a Living – even if there are obvious technological changes relevant to account for this.

[14] Paul Henley also provided enriching individual feedback before the final submission, suggesting for instance to aim at the actual 35 minutes for its length. He also suggested the films current title – my provisional title was out of season.