Peasant crafts come into fashion

At the beginning of the 20thcentury, the rise of a bourgeois interest for peasant culture engendered the collecting and exhibiting of traditional crafts. Between the world wars, the development of industry prompted a contradictory stance - lamentations over the loss of traditions and pride for innovations - while the Fascist regime led the discourse on regionalism. In the aftermath of World War II, efforts to salvage Sardinian craft included the creation of a regional institution, the I.S.O.L.A., and the establishment of an Ethnographic Museum in Nuoro. During the 60’s, Sardinia became a travel destination, redefining craft as a tourist art.

After Italy’s unification in 1871, the relationship between national government and local outposts prompted a debate on the autonomy and specificity of each Italian region. Sardinia’s insularity and its position at the center of the Mediterranean Sea had opened it to a wide range of cultural influences over the centuries. However, it had also led to isolation, backwards economic conditions, and the preservation of ancient customs, especially in the inner areas. The widespread persistence of the traditional dress in daily usage was the most visible sign of a conservative culture. Brigandage was the paroxysmal and criminal manifestation of the resistance to cultural and political assimilation. However, the development of the mining industry and the rise of a bourgeois class in the urban centers were strongly accelerating social change, engendering a concurrent feeling of nostalgia for what was perceived as the authentic, vanishing culture of the island.

The increasing success of Grazia Deledda’s short stories and novels sparked the interest in Sardinia, and a new generation of visual artists trained in mainland Italy put themselves at the forefront of a regionalist movement. These artists soon developed a curiosity in the island’s material culture, which encompassed the appreciation of its formal and aesthetic features as well as its symbolic meanings.2 Peasants became the icons of a mysterious and fascinating primitive Eden, the proud offspring of Sardinian ancestors, keepers of a noble heritage, humble and yet solemn people, living a simple life according to nature’s rhythm.

At the same time, peasant arts started being heavily collected, sought for and cherished by highbrow and middlebrow classes, forged to satisfy an increasing demand, and used to inspire modern items that retained a flare of the antique, authentic pieces. This is especially the case of the furniture by Fratelli Clemente, a family of cabinetmakers from Sassari, who successfully renovated their production around 1911, introducing a distinctive line of furniture in “Sardinian style”. It is especially Gavino Clemente (1861-1947), the son of the founder Bernardo, who started touring the island in search of new and ancient artifacts. His peculiar position as cabinet maker and retailer allowed him to organize a profitable exchange circuit: he provided peasants with new and “modern” items and acquired at low prices traditional pieces, which he resold and used as a source of inspiration for his own production.3

This circulation stimulated local artisans to produce more, and for outer markets. At the same time, it deprived them of the original pieces, replaced by new models, thus endangering the cultural transmission of patterns, shapes, and techniques. The artisans’ social status was also affected by the process in an ambivalent way. On one side, the possibility of new markets and the appreciation showed by a bourgeois public strengthened their position. On the other, the inflow of industrial goods was to make their role weaker overtime.

Collection, trade, and revamp

In 1909, Clemente got in touch with Lamberto Loria (1855-1913), ethnographer in charge of the organization of the Mostra di Etnografia Italiana and the Mostra delle Regioni for the 1911 International Exhibition in Rome, part of the celebrations for the first 50 years of the Italian state. Loria aimed to provide an overview of Italy through the lifestyle and customs of its inhabitants, perceived both as part of a whole nation and as custodians of peculiar regional traditions. He conducted a campaign to acquire examples of material culture from all over Italy, associating with local experts, such as Clemente in Sardinia.

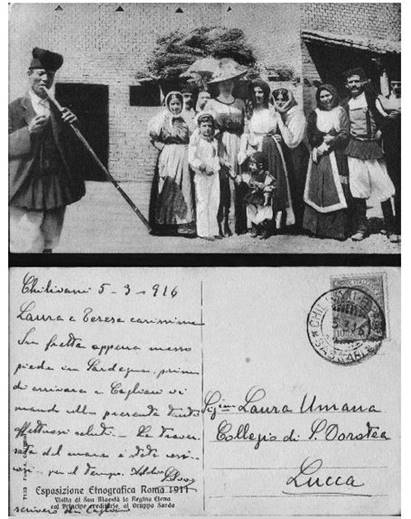

As a general criterium for collecting, Loria favored items with a flashy aesthetic and possibly an artistic value. Still, daily, simpler objects were also acquired for the sake of accuracy (Puccini 2005: 32). The exhibition extended into two buildings, the Palazzo delle Scuole and the Palazzo delle Maschere e del Costume. Besides, 14 regional pavilions presented the objects in context, displaying domestic locations and “typical scenes” animated by “real folk people”. The Sardinian pavilion, designed by the engineer and connoisseur Dionigi Scano with a pastiche of historical styles, included a fake nuraghe 4 and folk scenes enacted by Sardinian walk-ons (fig. 1).

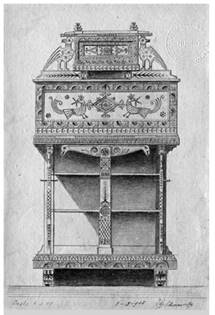

Gavino Clemente showed Loria around the island during his tour in 1910; further acquired peasant objects on behalf of the exhibition during the following year, with a devotion and enthusiasm that challenged the organizers’ patience and budget;5 and lent to the exhibition pieces of his collection. At the same time, he was preparing his participation in the Esposizione Internazionale dell’Industria e del Lavoro in Turin, also part of the 50 years celebrations. There he exhibited a “Sardinian living room” with several pieces of furniture embellished by decorative patterns from traditional wedding coffers, tridimensional versions of baskets, distaffs and filigree jewelry, and peasant textiles and pottery to complete the look.

Featured on the pages of L’Artista Moderno (1911), the ensemble was praised for the virtuosic execution and the creative use of popular motives marking the beginning of a successful line of Sardinia-inspired home furnishing. Shortly after, for the commission for Grazia Deledda’s study in Rome, Clemente produced neater, simpler pieces to accommodate his patron’s taste (fig. 2). The writer epitomizes the ideal connoisseur for this kind of production: fashionable in shape and high in craftsmanship, it retained a cultural value and the ability to assert the ethnic identity of the owner, overturning the negative associations that peasant art had with subalternity with positive qualities of refinement and social sensitiveness.

Source: http://www.isresardegna.it/index.php?xsl=528&s=62491&v=2&c=4114

Figure 2: Gavino Clemente, Furniture for the Grazia Deledda's study in Rome

Clemente embodies two different views of Sardinian crafts: as a collector and an intellectual, he valued the ancient pieces and the capability of the local artisans to reproduce them “as they were”; as an entrepreneur, he focused on the commercial opportunities inherent in modernizing traditional crafts, or their use as a source of inspiration for novel furniture and decorative arts.

A large coeval canvas by the local painter Giuseppe Biasi (1885-1945), Festa Campestre (fig. 3), is an excellent example of the romanticized view of peasant life and the rising interest for traditional costumes, saddlebags, and jewelry. Interestingly enough, at this point in time, the focus is on customs and habits but not on the artisans themselves. Material culture “appears” on Sardinian people, but little attention is given to its production.

It is worth noticing that what seemed exceptional and specific of Sardinia to the intellectuals engaged in social and political claims was, for the most part, typical of various cultures. As Focillon (1931: 17) would have argued some years later, traditional craft was “more international than national in its essential attributes”. In 1913, The Studio 6 treated Italian popular art as the expression of a common culture, with some specifications. “The Sardinian women - wrote Elisa Ricci (1913: 21-22) - are also skillful weavers and manufacture characteristic materials.” Their designs were “coarser, purer and freer in every way”. Castelsardo was the village where the art of straw-plaiting was “seen as its best”, with baskets of remarkable “charm and beauty”.

Embroidery and lacemaking were by far the most practiced, praised, and sought for kinds of women’s crafts. “To invite any Italian woman to embroider is tantamount to asking a German to drink!”, sustained Ricci with a jingoistic joke (1913: 24).

Gendering Sardinian crafts

The embroidery industry, which in some cases employed almost the entire female population, was supported by pioneering national humanitarian initiatives as Industrie Femminili Italiane (I.F.I.). This joint-stock company aimed at organizing women’s labor, opened “international markets for the Italian women’s products”, offered “advice from the higher forms of art”, and eliminated “the middlemen who exploit the timid labor of women” (Albano 1906: 10).

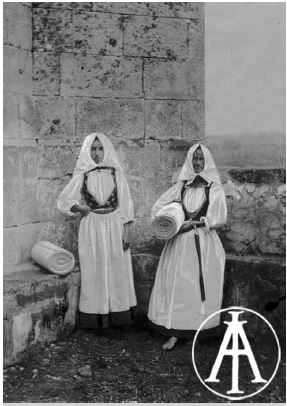

The social condition of women artisans was precarious and raising concerns among intellectuals and politicians. The economic gain from such activities was so low that the poorest part of the population had abandoned them to work full time in the fields, and only the well-off farmers continued to craft (Albano 1906: 284). A 1915 photograph from Ricci archives shows two barefoot vendors of orbace - the coarse woolen cloth typical of the region - witnessing both the existence of external demand and the difficult conditions of such commerce (fig. 4). Pottery-making was generally a family business, with both men and women involved to serve the needs of their communities; woodworkers and goldsmiths were usually male and professional artisans. Otherwise, the lack of professionalization was a widespread issue, even among men (shepherds used to carve wood or make reed or olive baskets in the spare time in the fields, or during winter idle times).

Source: https://www.inasaroma.org/patrimonio/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/ELISA-RICCI-102194-RECTO.jpg

Figure 4 : Elisa Ricci, Orbace Vendors, 1915

Embroideries and weaving pertained almost exclusively to women. Despite their high technical complexity and their material and aesthetic quality, they did not help the social status or the economic wellness of their makers, highlighting a gender problem embedded in the discourse of peasant craft. Parker (1984) and other feminist thinkers focused on how artistic practices historically connected with women’s labor have continuously been de-professionalized, de-evaluated, and pushed in a polluted space as a means of dividing the realm of “real creativity” from that of the merely decorative (Pollock 1999: 25).This comes as no surprise as the discourse of the other is embedded in the canon, and women’s crafts in the context of rural Sardinia represent a double otherness, combining gender, class, and culture. Griselda Pollock (1999: 3) defines the canon as “the retrospectively legitimating backbone of a cultural and political identity, a consolidated narrative of origin, conferring authority on the texts selected to naturalize this function”. In this respect, the ambiguous and contradictory nature of craft is striking. It did absolve that legitimizing function, becoming an identity marker and an ideological construct, but only when selected, acquired and appropriated by the dominant classes. One of the reasons for such appropriation was the rising awareness of the fragility of traditional heritage and a general feeling that the disappearance of folk arts was ineluctable. The countermovement to invert the process or preserve what was left saw museums at the frontline.

The war temporarily halted the collection of peasant artifacts and the production of “Sardinian style” furniture. However, Clemente retained his enthusiasm for the folk arts, playing a crucial role in keeping this interest alive, especially among artists, within the broader international movement of art nouveau, favorable to decorative arts.

After World War I

In 1917 Giuseppe Biasi organized a Mostra Sarda at Palazzo Cova in Milan (Altea and Magnani 1998: 96-97), pairing artworks by the most notable Sardinian artists with popular art. In the same year, the painter joined, together with the sculptor Francesco Ciusa (1883-1949), the national association Rinnovandoci Rinnoviamo, aimed at “the development of all the artistic applications derived from ethnographic characters” (Chini, Cifariello and Nomellini 1917).

A couple of years later, Biasi took a trip with the architect Giulio Arata to several Sardinian villages, in search of material for a publication, for inspiration, and finding new ways to make profits through peasant crafts. However, the expedition did not produce any tangible results in Biasi’s practice, and the project for the book was put on hold for several years, as we shall see further on in this essay.

Giulio Arata did publish two long contributions in 1921, on the pages of Dedalo - a fine and applied arts magazine directed by the art critic Ugo Ojetti -, illustrated by traditional artifacts from the most notable collections of the island (Lovisato, Manconi, Pischedda, Sanjust-Amat, Scano, and of course Clemente). The texts, supposedly an anticipation of the book, witness the vogue for Sardinian peasant crafts, but also an increasing skepticism on the possibility of using them as a source for modern art.

“Until a few years ago - wrote Arata (1921a: 698, my translation) - peasant art of the rural masses was not taken in any regard, if not ignored or even despised: today we remove the specimens from the walls of the old houses and cherish them with a curious and benevolent eye […]. It’s an evident demonstration that we live in a period of attempts and anxious research, a clear hint that our age is one of preparation or decadence […]. We should not delude ourselves or hope that the strong and vibrant art we all are waiting for can spring from this our study and admiration alone.”

Biasi must have felt the same way as, in the end, he never pursued decorative arts. Yet, many other artists in Sardinia tried that road, notably using ceramics. This technique offered maximum creative freedom and relatively high status, given not by the actual condition of rural potters, but by the use of the medium by art nouveau artists (Camarda 2009).

Arata had a pessimistic view also on the authentic peasant arts, which he saw fading due to the “continuous and slow ethnographic upheavals caused by industrial infiltrations”. He explained that “the decorative motives of that art […] go simplifying; the rhythmical conduct of the stylistic schemes stiffens; the wool dyes, which the women loved to obtain by herself from natural elements, are now replaced by industrial chemical combinations; and the thick fabrics are thinning because of the high cost of the raw material” (Arata 1921b: 780-781).

At this date, Arata’s position was against the grain of several attempts to salvage the traditional crafts. In the U.S. after World War I, for example, the concept of a “usable past” emerged. This term, which could easily apply also to the Sardinian scenario, expressed the need for “a cultural memory that could provide […] a comfortable sense of continuity or being part of a tradition” (Clayton 2002: 1). Anything but a spontaneous phenomenon, the construction of such cultural past discarded the idea of few exceptional masterpieces, looking instead at the humbler creations then defined as folk art - a category encompassing a wide range of objects, produced by different groups of individuals, with different backgrounds, professions, and scopes, but linked by the manual means of production.

Exhibiting crafts

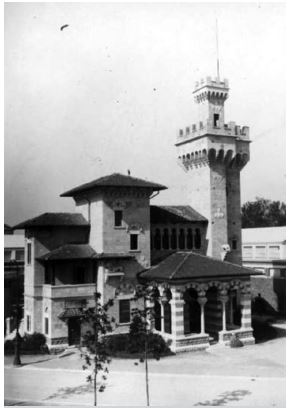

In 1923 Sardinian crafts were exhibited both at the Fiera Campionaria in Milan and the first Biennale Internazionale delle Arti Decorative in Monza; in 1924, at the Mostra Regionale di Arte Rustica, organized on the cruise ship Italia directed to Latin America (Mantura, Maino and Osio 1999); and in 1925 at the Mostra d’Arte Sarda at the City Hall of Cagliari. The partial success of these events led to the decision to build an entire permanent Sardinian pavilion for the Fiera Campionaria in Milan. The pavilion, also by Dionigi Scano, combined different architectural styles and elements taken from actual medieval buildings and opened in 1927 (fig. 5).

Source: http://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/img_db/bcf/u3020/1/l/249_1929_249.jpg

Figure 5: Dionigi Scano, Sardinian pavilion for the Fiera Campionaria in Milan, 1927 (picture taken in 1929)

The painter and influential intellectual Filippo Figari (1885-1973) decorated the interior with a triptych depicting the peasant Feast of Saint Constantine, portraying rural villagers as heroes and heroines from some medieval epic to assert the nobility of the Sardinian nation. Some years before, Figari (1996 [1924]) had published a text on Sardinian culture, in the form of an allegoric fairy tale: a bourgeois group from afar arrives in a mysterious and savage land, expecting monsters and dangers, but finding a girl instead, at the loom, composing fantastic images and dazzling decorations. In a comic turn of the events, the travelers start hoarding carpets, carved woods, jewelry, and laces, and so the story goes on, the point being that Sardinia was not a savage land, but one with a precious, ancient civilization, worth to be cherished and preserved.

Figari - while apologizing for his “backward-looking idea” - lamented the absence of a museum to gather and preserve the beautiful things which adorned the peasant houses, now dispersed, sold for little money, and replaced by cheap, worthless industrial wares. Indulging in describing the creative process of the peasant craftspeople, he spoke of the instinctive farmer, carving wood out of an almost unstoppable need to represent nature, and especially of the weavers, to whom the highest praises were reserved: “they are countless artists who weave with the fullest freedom of temperament; as a painter with his palette follows his inspiration and fantasy in composing, so our women tune the fabric to the song of their love and the singing to the rhythm of the loom”.

The girl at the loom would thus have become an unmissable presence in every exhibition on Sardinian craft, a timeless icon of a harmonic rural life.

To complement weavers and other artisans, the 1927 fair in Milan displayed produce, dairies, wines, and posters on the mining industry, sources of economic development. Folk-inspired decorative arts and actual traditional crafts provided a “gentle note”, displaying “a triumph of colors and poetry”, the ingenious creations by “the skilled hands of the [Sardinian] housewives”. Not much something to build an economy on, these objects seemed to belong to a museum, the only way to ensure that “this rich heritage would not be lost” (Deledda 1927a: 50-51).

Small Sardinian industries

In the meanwhile, the E.N.A.P.I. - Ente Nazionale per l’Artigianato e la Piccola Industria - was founded in 1925 to foster craftspeople and small industries. The institution organized courses, exhibitions and publications, notably in 1928 the survey on Sardinian crafts Piccole Industrie Sarde.

The author, the customs officer Amerigo Imeroni, is very accurate in sketching a picture of the situation on the island. We learn that on a population of 865.000 inhabitants, 6700 were textile workers, 4900 embroiders and lace-makers, 7800 basket weavers, 4730 woodworkers, 2100 metalsmiths, 670 goldsmiths, and 1000 potters. He listed the most important collections and the newest vocational training initiatives integrating or replacing traditional apprenticeship, fostered by the new Ente di Cultura e di Educazione della Sardegna, such as the Scuola d’Arte Applicata di Oristano (1925), the Istituto Artistico Industriale in Sassari, the Scuola Professionale Femminile (1926), the Bottega d’Arte Ceramica (1927), the Scuola del Tappeto Sardo and Sardinian Ars in Cagliari (directed by his wife Vittorina Imeroni Porcile), and the vocational school and workshop in Isili (Imeroni 1928: 8, 61, fig. 6).

Although crafts were ideologically proposed as the most profound expression of Sardinia’s soul and psychology (ibid.7) and defined as its “anonymous, pride of the people, universal heritage” (ibid. 63), the author could see the changes in place and the crossroad right ahead.

His judgment of the “Sardinian style” furniture of the Clemente brothers was appreciative, yet with a caveat. On one side, they originated a positive movement of appreciation for peasant carvings. On the other side, they could easily slip into useless virtuosos or exaggeratedly exuberant decoration, betraying the severe elegance of their original models (ibid.36-37).

Additionally, he acknowledged the precarious condition of craftspeople, plagued by middlemen’s speculations, lack of organization and training, fiscal pressure and high transportation costs (ibid.24). While peasant people gave away their most valuable pieces of cultural heritage, “bazaar’s odds and ends” (ibid.47) flooded the internal market, polluting it and destroying the “primitive simplicity” (ibid.50). A discouraging scenario to which Imeroni reacted with a plea to support traditional crafts, as they could still have a place in the economic development of the island, complementing on one side agriculture and pastoralism, on the other the mining industry (ibid.62-63).

Imeroni’s point of view, focused on craftspeople and their livelihood, paired with coeval considerations such as those of the anonymous editor of Mediterranea: “It would be beautiful - he affirmed - if each Sardinian, when building or furnishing his home, would buy every object that, back in the day, provided delight and luxury.” (Deledda 1927b: 29).

The discourse on craft traveled on parallel, sometimes intersecting roads: a heritage of the past or a hope for the future, something to transform or something to preserve.

A museum for peasant arts?

Around 1930 the positions of Carlo Aru (1881-1954) and Antonio Taramelli (1868-1939) sum up the issue at stake. Aru, an art historian at the University of Cagliari, did not believe that peasant arts could have a future in the industrial age. “As every dead thing, the products of popular art go slowly disappearing from the circulation to reach an honorable burial in the vitrines of the museums. They cannot, as a rule, be revived by the artifices of the schools or small industries. Artifice is not art, and the cultivated spirits don’t have nor can have the spontaneity of the rural maker.” (Aru 1931: 11)

On the other side, Taramelli, archeologist and the head of the Museo di Antichità e d’Arte in Cagliari (also a collaborator of Loria in 1910), wanted a living museum to represent rural life and its industries,

“still full of charm and harmony, sparkling with colors, vivid with a characteristic and impressive inner force, capable of arising the greatest sympathy in the modern world and of generating, through an accurate discipline and a loving preparation, a beneficial activity to elevate the spirit of the local craft, and a stream of production which can be, as it partially already is, a source of economic wellbeing for Sardinia.” (Taramelli 1930: 41, my translation)

Taramelli rejected the idea of a museum modeled after the 1911 Sardinian pavilion - “a little Sardinian village, with a little church and a bell tower, the tiny houses, the fountains, the rooting piglets, etc., in conclusion, the Sardinian bidda so full of character,7 recorded during its daily life”. (ibid.43) advocating for the enlarging of the archeological museum with an ethnographic section, following the historical developments up to the present days.

Special consideration was reserved to weavers, hailed as the “Sardinian arachnes”, rightfully listed in the ranks of “the admirable women of Italy” (ibid.46).

Women, crafts, and the fascist regime

This appreciation of women’s labor is quite striking at a date when the fascist regime had steadily established its power on every aspect of Italian life and culture. Victoria De Grazia (1993: 7) analyzes the multifaceted condition of women under the regime: cast in the role of the generating and nurturing mothers, discriminated by law in the labor market, excluded from the formal political system. It was a long process of erosion of women’s rights and their “nationalization”, although class and custom strongly affected the experiences of Italian women under the regime.

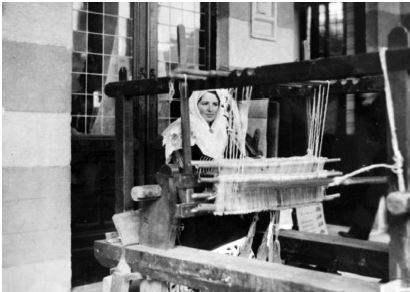

Three scenes from the Sardinian pavilion of the Fiera Campionaria of Milan in 1934 highlight how the progressive marginalization of women enters and complements the discourse on craft. In the first picture (fig. 7), a woman fully dressed in a peasant costume, her head covered by a precious embroidered veil, weaves at the traditional horizontal loom, the kind commonly used to produce textiles for the daily usage. Overall, the scene conveys a sense of quiet domesticity and represents well the image of the woman as the “angel of the hearth” pushed forward by the fascist propaganda.

Source: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/fotografie/schede/IMM-u3010-0001228/

Figure 7: Weaver at the Fiera Campionaria in Milan, 1934

The second picture (fig. 8) might seem alike, but a few details suggest a different story. The woman has no veil nor handkerchief, but a stylish haircut, and her loom, although also a simple horizontal one, has many more elements, which allows for complicated patterns. On the loom and around the stand is an exhibit of various small-size, ready-to-buy pieces, decorated with modern deco figurines of peasant women, in the fashion of the regionalist decorative popular at the time.

Source: http://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/fotografie/schede/IMM-u3010-0001231/

Figure 8: “Modern” weaver at the Fiera Campionaria in Milan, 1934

The last picture (fig. 9) is exceptional in two regards: it shows a semi-automatic loom, and a male weaver operates it. That kind of machine was intended for large-scale production, although the textile design is strictly traditional. Even if this kind of loom might have been used in Sardinia at this date, its presence is not acknowledged by the contemporaries.

Source: http://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/fotografie/schede/IMM-u3010-0001230/

Figure 9: Male weaver at the Fiera Campionaria in Milan, 1934

Also, men indeed engaged at various levels in the fabrication of textiles: some periodically roamed the villages buying wool for the weavers, others dealt with the business. Giuseppe Piras Mocci, the husband of the weaver and entrepreneur Filomena Piras Calamida in Isili, ran the family company (Caoci 2005). Maestro Efisio Pintore from Nule, also the husband of a professional weaver, in 1928 improved the traditional loom adding a comb to keep the warp well-stretched: an innovation progressively embraced by all the weavers of the village (Bentzon 1965: 62). However, male weavers were exceptional - if not legendary. An early 19thcentury saddlebag signed “Giovanni Murru” 8 is the only indication that some form of male weaving must have existed in the past. In Sant’Antioco, Italo Diana specialized in weaving the byssus or sea-silk, a tuft of filaments secreted by the Pinna nobilis at the time harvested for this scope.

I contend that the scene was somehow staged both to highlight the contrast between female and male labor, the first one confined in the perpetuation of familiar traditions or cutesy amateurish decorative arts, the second oriented toward the industry and actively pushing through modernization.

During the 30’s, one-quarter of the Italian workforce was female, but women’s status as workers was precarious. Through “protective laws, propagated discriminatory attitudes and enacted statutory exclusions”, the regime allowed women - an abundant source of cheap labor - to work for the big capital,9 but kept them in a subaltern position, to secure for men the role as heads of household (De Grazia 1993: 167).

However, if we consider Imeroni’s 1928 statistics, in Sardinia almost 70% of craftspeople were women - 100% in the most profitable sectors of weaving and lacemaking. And yet even Imeroni, who is very generous in praising the Sardinian shepherd for his self-taught, independent, driven-by-nature creativity (Imeroni 1928: 31), makes a point of mentioning the most skilled male artisans, and is not as much ready as to tribute women the same honors. Discussing carpets and tapestries, he recognizes them as the most striking and valuable among Sardinian craft forms, but they are always the product of a village as a whole, praised as objects without reference to their maker, or the latter addressed with the word artifice (i.e., maker), conveniently ambiguous in terms of gender,10 or even through a metonymy (the looms).

While it is difficult to assess whether and how much the primacy of women in the most substantial artisanal trades led to their empowerment, it is clear that their role could not be easily set aside, even more so after the secretary of the fascist party, Achille Starace, chose the orbace 11 - the coarse but sturdy Sardinian woolen cloth - to manufacture all the fascist uniforms. This brought a centralized organization of the production and the commercialization, improvements and standardizations of the processes, the replacement of the natural dyes with chemicals, the installation of electric fulling mills, the institution of collection centers, and the promotion of the textile beyond Sardinian borders (Vinelli 1935). The semi-automatic loom at the Fiera Campionaria might well have been an example of the innovations introduced by this shift. In 1936, a documentary by the Istituto Luce could assert that the production of orbace was “the main traditional activity in Sardinian craft”, employing more than 3000 craftswomen on 1000 looms. The film takes great care to include male labor in the process, showing men carrying, sorting, and dyeing the cloth - the latter now a “modern” operation.

This gender opposition is a recurrent feature in the printed matter of the times, as we have already seen and as this quote from 1927 well exemplifies:

“Contrary to a common bias spread among collectors, peasant art here, for the most part, did not come out of feminine hands, if we consider it as creative work. Armorers, woodworkers, saddlers, goldsmiths and carvers of small horn or wood objects were, in this regard, the stronger producers. Yet it is true that, in quantity, nowadays textiles and embroideries or laces made by women prevail because here such works never had, as it was in the main centers, the importance such as to require the intervention of male craftsmen.” (Albizzati 1927: 14)12

The orbace represented a conundrum and a challenge for the fascist propaganda: the narrative which emerges from the coeval accounts is that of a raw, primitive skill of the good peasant housewife,13 virilized and modernized by the regime with the injection of new “fascist” energy. It is also a good case study to appreciate the fast changes occurring in the world of crafts at that time. Two Luce newsreels, also from 1936, show how, although in different hues, the same process was happening in other sectors. The manufacture of cork in Tempio focused on a few products (cork stoppers and cork wool) and employed both male and female labor in well organized, proto-industrial workshops. With a production of around 100.000 quintals per year, cork was a significant resource for the Sardinian economy, which hosted two thirds of Italian cork oaks (Ricotti 1936a).14

Basket weaving was utterly in women’s hands, practiced outside the domestic setting by women who had, for the most part, given up the peasant costumes. The most significant source of revenue for the village of Castelsardo, it occupied at least forty (Ricotti 1936b).

Filet crochet, which already in 1928 was shipped to France, Belgium, England, and the U.S., for a total value of one million liras, was made by individual artisans and organized workshops, such as those of Olimpia Peralta Melis and Diodata Delitala in Bosa, of Cicita Delitala Passino and Maria Manconi Passino in Oristano, each with 500 workers or more, although most of them also worked in the fields (Imeroni 1928: 24). The surnames of the business owners, indicating a noble lineage, also point at that class gap discussed by De Grazia, which should make us suspicious of any attempt to generalize the condition of women under fascism.

I would argue that this strong presence of women in crafts was among the reasons why it was progressively marginalized in the discourse of the economic development of Italy, pairing with the anti-regionalist turn of the regime during the 30’s, the physiological changes in fashion, and the progressive standardization of production.

Loss and recovery

When Arata and Biasi finally published their book Arte Sarda in 1935, times had changed since their 1919 expedition. The language, the abundant references to ethnicity, purity and nation, and the sexist remarks reveal a rewriting in tune with the rising concerns of the regime. Overall is the lamentation over the corruption of the authentic spirit of tradition, and with it goes away the idea of making money out of it:

“Schools have disappeared […], workshops are worn out, institutions dispersed, and yet, the regional peasant production, sheltered by the domestic walls, where it still lives and thrives in the practical traineeship of family collaboration, cannot and must not debase itself in the speculative empiricism of a misunderstood modernity.” (Arata and Biasi 1935: 5).

Placing traditional crafts in a mythic past of purity, a melancholic reminder of the corruption of present days, reinforced the counteractive idea of a museum, which regained strength thanks to an article on Nuoro Littoria, a newspaper of the regional fascist party, advocating for a museum of peasant arts in Nuoro, the very center of the island.

The Mostra delle Arti Popolari della Sardegna in Cagliari in May 1937 was a further step towards the creation of such a museum. Opened by a sacred art section - a sign of the increasing catholic influence at the end of the 30’s - the exhibition displayed “old customs and traditions, of what by now belongs to the past and it has irretrievably disappeared” (Levi 1937: 182), presenting different objects according to rudimental museological criteria, less theatrical and more taxonomic.

Soon the war put, once again, things on hold. Sardinia was severely hit by the war, both socially and economically. At the end of the conflict, the situation on the island was dramatic, and the crisis of crafts well reflects the general one.

Among the recovery initiatives within the frame of the Marshall Plan was the touring exhibition Italy at Work. Her Renaissance in Design Today, organized by the Art Institute of Chicago with several institutional partners both in the U.S. and in Italy. “As much a trade show as a cultural event” (Sparke 1998: 60), Italy at Work aimed to offer a comprehensive overview of Italian ingenuity in design. While industrial production appeared as “the future”, there was also an appreciation for handmade goods: they could fulfill the need for a more humane approach, allowing for an optimistic view of the future.

Considering the persistence of Sardinian crafts and its collectability in the pre-war period, its marginal role in the exhibition is striking. Grouped with the other regions of Southern Italy, Sardinia was presented as untouched by modernity and out of history, a place where “the traditional peasant crafts […] continue much as before”. In these underdeveloped regions - explained the curator Meyric R. Rogers - “the omnipresent blight of poverty and lack of industrial resources encouraging enterprise have as yet been too powerful to permit a constructive reaction to the destructive forces of war” (Rogers 1950: 19).

The weaver from Nule Quirica Dettori, presenting a typical “flamed” carpet, was the only representative of Sardinian crafts.15 Her workshop, quite big and well organized before the war, must have been one of the few to stay operational after the war (fig. 10).

Source: https://www.artic.edu/exhibitions/3704/italy-at-work-her-renaissance-in-design-today

Figure 10: Carpet by Quirica Dettori exhibited in Italy at Work: Her Renaissance in Design Today, The Art Institute of Chicago, Mar 15-May 13, 1951

Right after the war, also the E.N.A.P.I., having outlived the regime, resumed its activities under the leadership of the architect Ubaldo Badas (1904-1985) and the artist Eugenio Tavolara (1901-1963). They roamed the island to salvage what was left of traditional crafts, enrolled skilled craftspeople in teaching the younger generations, encouraged the organization of work, and promoted its outputs in the market.

In line with a renewed optimism in the possibility of crafts, they slowly rebuilt the trust of craftspeople in their trade and the appreciation of the public for their production. It was not an easy task. At the first Fiera Campionaria in Cagliari in 1949, the presence of crafts was residual while industrial goods - cheaper, more practical and abundant - seemed to offer the producers steadier and higher salaries, the consumers more affordable and modern appliances for the daily life. Also, the cultural values so strongly represented by peasant arts in the first half of the century were now better embodied by the archeological remains of the Nuragic civilization, a sensation at the 1949 Mostra di Arte Sarda at the Fondazione Bevilaqua La Masa in Venice and, since then a palingenetic symbol of the original strength of Sardinian people and their links with a broader Mediterranean culture.

These dynamics are relatively well known, thanks to the seminal studies conducted by Giuliana Altea and Marco Magnani on the post-war Sardinian artistic scenario. Altea and Magnani (1994, 2000) researched Tavolara’s efforts to adapt the traditional designs to the modern taste and needs, in a difficult balance between respecting the cultural heritage and the autonomy of the craftspeople and innovating what was necessary to break into the national and international markets. The plan included the invention of new “traditional” shapes and decorative objects very much attuned with the 50s’ taste for organic, streamlined and neo-primitive forms. A smart move was to pair the prehistoric past of the island with the folk traditions, encouraging, especially with the help of the artist Mauro Manca, a production of Nuragic-inspired crafts (figurines, vases, and textiles).

Cooperation between artists and artisans - inspired by Picasso’s experience in Vallauris - was considered a viable road to guarantee cultural and aesthetic sensitiveness.

Set aside any concerns on the loss of authenticity and the disappearance of peasant culture, Tavolara and his political supporters carried on a modernist agenda, assembling visual resources for artisans and designers, and educating the new generations of Sardinian people to appreciate and identify with their cultural heritage.

The Sardinian Institute for the Organization of Artisanal Labor (1957)

The regional government supported the E.N.A.P.I., working in parallel to develop its initiatives, a process culminating with the founding, in 1957, of the I.S.O.L.A., Istituto Sardo Organizzazione Lavoro Artigiano, an institution which acted on the world of crafts on many different levels: it trained craftspeople; pushed them to create cooperatives or other forms of organized labor; provided the design and the materials to craft the objects; put together a portfolio of clients and organized plenty of exhibitions and trade shows to promote and sell the works.

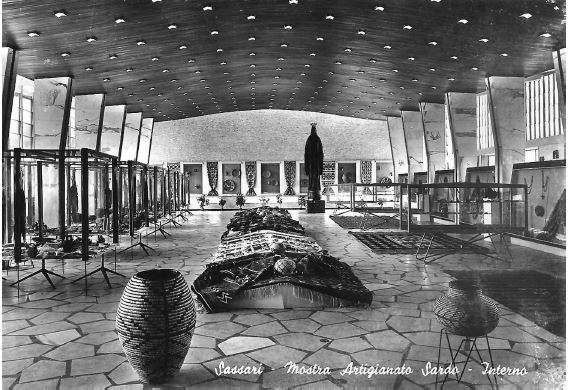

Already in 1956, Ubaldo Badas had completed the Padiglione dell’Artigianato in Sassari, a pavilion aimed at hosting events related to crafts. The building was a declaration of modernity in itself: an airy hall full of light, with organic, streamlined shapes, enriched by sculptures, bas reliefs and paintings on ceramics, the joint effort of artists and artisans (fig. 11).

The pavilion opened with the first Mostra dell’Artigianato Sardo, the result of years of preparations, presenting the renewed production along with historical pieces, generating a good reception on a national level.

A year later, Sardinia had a prominent place at the IX Triennial in Milan, in the Mostra delle Produzioni Popolari Italiane - an exhibition that witnesses the general interest in craft - and specifically in the Mostra delle Produzioni d’Arte della Sardegna. The latter was a special exhibition, hosted in a pavilion built for this very purpose in the Parco Sempione, which brought almost the entire content of the show in Sassari to Milan, signaling Sardinia as the Italian region at the forefront of the new craft movement.

Gio Ponti, the Italian leading architect and designer, enthusiastically advocated for Sardinian crafts, which he defined as “real craft, namely works which industry cannot replicate […]”, virtuosic in its execution and original in its aesthetic outputs. Something deserving to be known to the Italian and the international public, and to be fashionable as Scandinavian and Japanese design (Ponti 1957: 37-39). Ponti’s enthusiasm grew further after his visit to the VI Mostra dell’Artigianato Sardo in 1962 - after the great success in 1956, the exhibition in Sassari had become a yearly appointment.

Praising Tavolara and his collaborators on the pages of Domus, the architect made a fervent plea: “May they [the Sardinians] defend their arts from the pitfalls of success, from the contamination of those buyers who don’t care for quality and genuineness.” In a revival of the pre-war lamentation for the loss of authenticity, Ponti’s claims were ambiguous: he was perfectly aware of the designers’ intervention (he praises Tavolara several times for his work) but also realized that Sardinian crafts as the product of an ancient, close to nature and primitive (in a good way) popular spirit was a better story to sell to the eager bourgeois buyers.16 To convey this “good primitivism”, the article’s cover picture showed a swordfish upper jaw placed into the sand like a savage Excalibur, followed by other images in which craft objects rested on rocky natural settings.

In the same issue of the magazine, Tavolara himself spoke about Sardinian craft, considered as part of the feminine domestic realm, with a subtle shift from the pre-war discourse. Women, no more deprived of creativity and ingenuity, were now the empowered protagonists of the spiritual and economic rebirth of the island:

“As a matter of fact, they are the mind of the house. The tireless work they are subjected to since their childhood can’t extinguish their intelligence and their sensitivity. Give these women a loom, a bit of linen or wool, a tuft of asphodel or palm, and their stumpy and cracked hands will become light and skillful. Their tapestries, their carpets, their baskets, their fabrics and their linens, their festive bread and fantastic sweets are already known everywhere, and maybe they are about to give Sardinia a primacy.”

The Italian resurgence of handicraft and the prominent role women played in it suggests, as Penny Sparke (1999: 63) noted, “a deviation from the dominant, masculine model of modern design”. According to Sparke, the Italian effort to support crafts shows “an ambivalent relation with international modernism” derived from “an anxiety instilled by the suddenness and lateness of its transformation from an agricultural to an industrial economy”. While anxiety and ambivalence might have been the daily bread in the problematic post-war context, the revival of crafts was a global phenomenon, part of the palingenetic search following the war’s disruptions. Besides, in many cases, and particularly in Sardinia, handicrafts were not an alternative to industrial design, but the only available means of production, and the site to highly specialized skills. What differentiates the craft movement of the 50’s from analogous trends of the first half of the century was the absence of nostalgia and the belief in craft as a viable road to development.

In this scenario, the shifting in the relationship between craftspeople and artists is meaningful: before, the artists found inspiration in peasant arts to develop their original “modern” artifacts, now they provided designs to crafters, leaving them the agency. Arguing that artisans were thus stripped of their creativity would be mistaking the very process of craft, based on repetition and oriented to the fulfillment of the recipient’s needs.

However, there were critical positions, stressing the fragility of the new vogue and the predicaments of a production endangered by the advance of industry.

“Sardinian crafts - wrote Filippo Figari (1996[1957]: 208-209) - had been a living and most active reality until the needs of men and times have swept away - as everywhere - the traditional forms of existence and economy […]. As we can’t expect from our farmers or our workers to show up in costume and work in costume in the fields, the factories, the mines, the harbors, so it is pointless to try and renew the miracle of an essential craft, alive and poetical within the Sardinian homes.”

The precarious balance achieved by Tavolara thanks to his deep understanding of both traditional crafts and the modern market, and his respectful attitude, which earned him the trust of craftspeople, broke shortly after his untimely death in 1963.

From modern crafts to tourist arts

Already in 1964, the annual exhibition in Sassari and a promotional initiative in Genoa saw a diminishing quality of the artifacts and, even more important, a shift in the promotion strategies. While, till that date, the “modernity” of Sardinian crafts was emphasized, later the craft object became the specimen of a “simple art, centuries-old”, untouched by modernity.17

A modernity which, on the other side, was rapidly changing the Sardinian scenario, primarily because of touristic development. From the early 60’s, various entrepreneurs began looking at the island as a holiday destination: in 1962, the birth of the Consorzio Costa Smeralda - a joint enterprise to develop the touristic infrastructure and promote the island - represented a turning point also for the discourse on crafts. Following these developments goes beyond the scope of this essay, it is enough to say that the massive arrival of holidaymakers (in 1969, there were already almost a million tourists) incepted the dynamics related to ethnic and tourist arts described by Nelson Graburn (1976, 2004). The I.S.O.L.A. and its organizational system slowly succumbed to the new needs of the market and the emergence of more profitable trades for the former craftspeople. The institution was suppressed in 2006, after a long period of decadence.

Memorializing craft

Back to the 50’s, the parallel efforts to musealize traditional crafts have drawn less scholarly attention. The drive to preserve and salvage originated from the now minority nostalgic, pessimistic take on craft originated in the first half of the century; however, its distinctive post-war features are worth of analysis.

In 1947 Clemente died, leaving his impressive collection to the Museo Sanna in Sassari, which displayed a special pavilion starting from 1950. In 1954, the regional government acquired the important collection of Luigi Cocco of the 19th and early 20thcenturies.

But the most vigorous efforts to memorialize traditional crafts and customs convened in Nuoro where, in 1951, the city council deliberated 18 to devote an area of the town to the construction of the ethnographic museum Museo del Costume.

The regional government stepped in a year later, and things were set in motion by assigning the project to the architect Antonio Simon Mossa (1916-1971), a prominent intellectual in the island, whose political views - oriented toward the political independence of Sardinia from Italy - and the extensive activity both in the private and public sector made him a perfect match for the new endeavor.

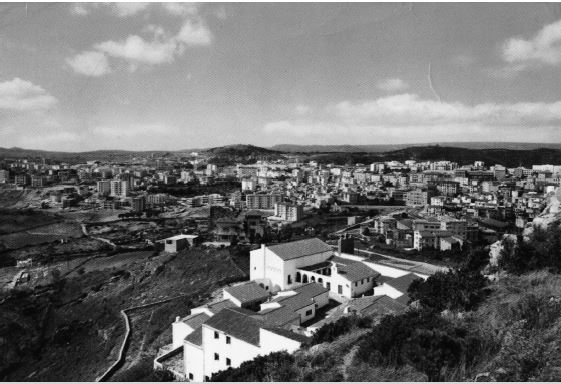

Strongly influenced by Le Corbusier, Simon Mossa’s previous architectures featured clean, squared volumes with large windows. His first project for the new museum was a massive, severe volume placed on a slope, surrounded by a park, and concealing an inner courtyard. However, this modernist architecture was discarded entirely, and in 1956 a new project was submitted, finally winning the approval of the administration. In 1957, the new building was inaugurated on the Colle Sant’Onofrio, a hill overlooking the town.

Ironically enough, the Museo del Costume was, at first sight, not different from the biddasarda ironically envisaged by Taramelli at the beginning of the Thirties: a “traditional” village, with tiny white houses and a few prominent buildings connected through a net of narrow streets. However, it would be unfair not to recognize the architectural quality of the complex and the serene atmosphere which Simon Mossa managed to achieve. A Catalonia enthusiast, he was undoubtedly looking at the Poble Espanyol in Barcelona. Still, his focus was on the humble rural houses more than the noble, famous architectures, an element that also separated him from the historicist take of Dionigi Scano.

Simon Mossa’s turn is better understood in the light of the post-war wave of interest for vernacular architecture, what the architect and critic Ernesto Rogers called “the tradition of the spirit against the false tradition of the dogma”, a way of coping with the fascist legacy and mending both the physical environment and the broken spirit of Italy by referring to the modest, spontaneous rural architecture (Sabatino 2010: 165-166).

In a coincidence that shows the timeliness of the moment, the Museo del Costume was inaugurated in 1957, shortly after the Padiglione dell’Artigianato in Sassari.

It was a flamboyant pavilion, aimed at finding crafts a place in the modern industrial economy, here a traditional village with a time machine effect to transport the visitors in a different dimension, one of authenticity, simplicity of life and beauty.

The museum was at odds with the concurrent development of the village of Nuoro, rapidly transforming into a mid-century town with cheap residential buildings and a wild urbanistic plan (fig.12). Also, it was an empty shell: the project of bringing craftspeople in to populate the village, work, and sell their goods right on the spot never caught on. Over the years, efforts to build a permanent collection slowly progressed toward a long-awaited opening in 1976, with a display focused on intangible heritage and a problematic presentation of traditional life as reified and detached from history.

I would argue that the I.S.O.L.A.’s representatives on one side and the promoters of the museum in Nuoro on the other approached the issue of craft from opposite sides, operating a shift between tradition and modernity, authenticity and innovation. A change made visible by the buildings they envisaged to fulfil their vision.

In a state of mind prompted by the disruptions of the war, the idea of tangible spaces to foster Sardinian’s material culture and shelter the vanishing traditions was paramount, to a point in which it seemed more important to secure the buildings than the items supposed to be held in them. Once these shrines for crafts were ready, they complemented each other in the foreground of a swiftly changing Sardinian economy and culture. For a short time, while Tavolara was alive and in the mid-century climate favorable to crafts, the I.S.O.L.A. managed to offer a viable option for craftspeople, soon wiped away by the rising of industrial design and the development of the tourist market. In Nuoro, the empty streets of the Museo del Costume - unable to define its content in the face of a fast, confusing modernization - stood for decades as a visual reminder of the impossibility for craft in the contemporary culture.