Introduction: the value of handicraft

When a bell breaks, it will never ring again (Martin Luther) Individual reality is allowed to appear only if it is not actually real (Guy Debord)

The struggle for survival of craft objects in the current system of consumption is, in short, the same suffered by the people who lose their identity and, consequently, accept anything else in return. As is well known, all the cultural, economic, and social metamorphoses that the handicrafts have been forced to undergo have been the target of numerous analyses within the current studies. In fact, the gradual decentralization that the forces of globalization have been introducing to their traditional and natural environments has led to a resettlement that, in the best-case scenario, has prolonged their agony or enabled their survival. Nevertheless, this resettlement has demanded and imposed a proportional mechanism to transform their own cultural values, as with any displaced element within a previous system, where its existence was guaranteed by its functionality.

The case we are analyzing shall be firstly placed in specific historical coordinates, secondly in an ideological axis and, lastly, at a fully socio-cultural level.1 Thus, we refer here to the historic moment in which the Galician handicraft production system - even though this remark could be also extended to the Spanish national level - entered its biggest turning point, the most acute phase of the crisis led by the economic changes suffered within the Spanish territory especially from the 1960s onwards. It has been considered, indeed, that it was between the 1960s and 1970s, when the traditional crafts reached the point of their virtual extinction as a sustainable economic and social resource in a Galician reality, that even though still economically based on the primary sector and demographically lied in the rural areas, a sudden process towards deagrarianization and urbanization was starting. All these changes, together with the unquestionable reasons of biology leading to the extinction of the dictatorship, state that, in parallel, the political order that had lasted for four decades since 1939 entered a phase of adjustment to new internal and external coordinates that require an equation of the Spanish political order to the western one, especially the European. The objective of this new equation was to accompany the new economic course regarding the market economy, which was at that time thrown towards the global expansion. In this manner, the Spanish historical process known as transición (Spanish transition to democracy), which took place peacefully and legally between the mid and late-1970s, was mainly based on a continued existence of ancient structural figures in the new established order. This way, this interplay of political and ideological variations is most probably a biased witness of the exhaustion of the handicraft production that reaches its highest point at that time. Nevertheless, the interplay also explains in the medium term the subsequent resurrection of the handicraft production, driven by the emergence of certain implied conditions within the process itself.

Metamorphosis or resurrection?

Seen as a resource for survival, one of the most visible examples of adaptation of the gear components that had supported the dictatorial system in the new emerging political entity is the case of several professional politicians that had served the interests of the dictatorship and that are still performing the same functions within the new democratic structure. The case of the politician Manuel Fraga Iribarne (1922-2012) is among the most relevant and well-known ones. His political career began in the mid-20thcentury, in parallel to his teaching activity and within the field of the dictatorship’s single party, FET-JONS. Manuel Fraga was a member of this party between 1953 and 1976, taking up leading positions and being responsible for the enactment or drafting of several legal provisions and political decisions with a strong ideological bias. Following the death of general Franco, Fraga was determined to lead the process of political transition and founded two successively conservative parties, in which he brought ancient serving politicians from the dictatorship while he acted as a constitutional rapporteur during the drafting of a Magna Carta that entered into force in 1978. However, his political career in the constitutional field at a national level was short-sighted, with several well-known electoral failures. This means that he applied for the position of president of the Xunta de Galicia (Galician regional administration) in 1989, after the refounding of Alianza Popular in the format of the current Partido Popular (People’s Party). Manuel Fraga obtained the position giving a speech that was significantly emotional, passionate in rhetoric, “Galicianist” when it comes to ideology, and pro-autonomy and pro-decentralization on the administrative side, which pointed out a new turn of the screw in his political and ideological evolution. Nevertheless, he turns at the same time the Galician People’s Party (PPdG) into an entity with its own dimension and discourse, as well as with remarkable discordances and disagreements regarding the national People’s Party, which only permitted Fraga’s political extravagances and ideological differences due to his undeniable influence and leadership.

It is necessary to consider that the path to power led to a series of synergies and transfers between the formal political order and certain background elements, integrated in the social fabric for centuries, and they used to base their efficacy on local patronage networks. At this point of the transition, those tyrannical structures would be later glimpsed in certain fields of democratic political power, especially regarding local and provincial governments, and they act as a recruitment and vote loyalty mechanisms depending on very specific interests that, in any case, require a certain reciprocity in the form of shares of power, autonomy and, of course, financing. Thus, the concept of fraguismo, deriving from Fraga, comprises a network of different levels of hierarchical power, where the main control of the Galician government (Xunta de Galicia) must enable and support subsidiary forms of a more localized power that, in some cases, challenged its authority but that, in return, guaranteed enough stability and vote supply to maintain the party control.2 It is not a minor fact that the area of activity of these local entities has directly to do with the Galician territorial distribution, as well as with its sociological and demographic peculiarities. Therefore, the areas that were subject to greater influence in the manner described above belong mainly to rural areas and are present in certain local governments and in the two least urban and industrial provincial governments, that is, Lugo and Ourense.

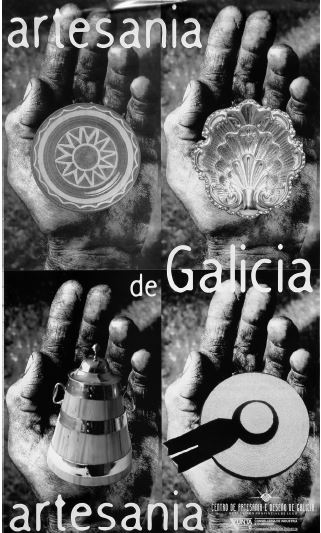

Fraga’s Galician government began very early to develop an ideological and propaganda project, based on the use of the Galician cultural heritage which,3 at the same time, implied a gradual change of its content but without affecting the container. From the very beginning, Fraga defended the differential nature of the Galician autonomy, and he even used to go back to historical notions such as the regionalism supported by Alfredo Brañas in the 19thcentury. These historical ideas were founded on the demand of a differentiated cultural identity for Galicia, but quite far from the maximalist political positions regarding the Galician historical nationalism.(Figure 1)

Source: Author’s photo peasantry

Figure 1: Institutional promotion of the Xunta de Galicia in the 90s of the 20th century. Three of the four elements chosen represent the

The relocation of Manuel Fraga at the forefront of the Galician autonomous government was carried out by means of his discourse differentiation in two parallel levels. On the one hand, the Spanish territorial unity was guaranteed through his own support and his political career. On the other hand, he assimilated diversity based on cultural contributions as a message and as an identifying note from his political project. It constituted a legacy, also linked to the Francoist society, in which folkloric events from the Spanish territories having a different culture were tolerated and encouraged.4 All this resulted in a power structure that equally combined a strong pragmatism in the economic and administrative field and a remarkable folklorism supported by cultural stereotypes in terms of propaganda and background emotional position statements.

It should be considered that this network would not be possible without the special contributions implied by the presence of a leading figure as Fraga Iribarne. Arising from his political past within the Francoist dictatorship and as seen above, his authoritarian behavior, his impulsive personality and his conservative political and ethical values joined this idea and concept network.5 Those conservative values were coherent with most of the Galician electorate, where the political project carried out by Fraga, Alianza Popular, had already succeeded in the 1982 elections, as opposed to what happened in the rest of Spain. Furthermore, several elements from his personal profile were added to his political one in order to be compatible with the new system of ideological references and the democratic political order. Firstly, Fraga, born in Vilalba, a small town in the province of Lugo, Galicia, formally claimed his Galician status in terms of cultural, ethological and linguistic aspects.6 Secondly, Fraga was born to a Basque-French mother and a Galician father who had both emigrated to Cuba and he lived there until he was two years old. Therefore, he frequently claimed his identity special feature of being a child of the diaspora.7 This cultural legacy, which used to exercise in the past and still nowadays exercises strong affectivity among the Galician population, especially in rural areas, was exploited for clear political purposes, since it was useful for basing Fraga’s sense of belonging on the traditional figure of the prodigal son returned from migration who makes a fortune thanks to his effort, hard work and perseverance, but who maintains the vital basic objective of returning someday to the place of origin.8 His connection to the so-called Galicia exterior (“external Galicia” or “Galicia abroad”) and the exploitation of the voting ground existing there have, to a large extent, their roots in this same mytheme created around him.9 In short, if we rely on a parallelism that is more pedagogical than real, we could state that the reinvention of Fraga’s political figure places him, seen as a leader, and the autonomous community section of the political party founded by himself, in a sociological status equivalent to the position enjoyed by the conservative nationalist parties that dominated politics in the Basque Country and Catalonia, also implying broad majorities and strong social prestige.

During the long period of Galician governments conferred to the People’s Party under the command of Fraga, the substructure of the tyrannical power that largely maintained its majorities in the elections was composed mainly of three territorial chiefs: Xosé Luís Baltar in the provincial government of Ourense, Francisco Cacharro in the province of Lugo, and Xosé Cuíña in several power domains within the provincial government of Pontevedra. All of these, in parallel to their own political role, were looming as close and pragmatic administrators that were able to give immediate and direct solutions but lacking obvious ideological charges and connotations. The exception was the case of Cuíña, who stood out for his highly pro-Galician and pro-autonomous political opinions, along the lines set out by Manuel Fraga. These circumstances were probably the ones enabling their cultural resource management, due to a series of reasons: firstly, this domain, in the context of the programmed dismantling of the Galician primary sector derived from the development of the European Common Agricultural Policy, was the only one accessible to local politics in a particularly under-industrialized area as is the case of Galicia. Secondly, the cultural policy was and still is one of the very few management areas that both the central and the autonomous community power were willing to give away. Lastly, cultural management turned out to be a format that was particularly susceptible to manipulation from a subjective and emotional perspective, to be submitted for an image policy that shouldered a well-defined ideological project: the re-writing and re-semantization of the past in a time when societal and economic changes had placed the Galician reality in the process of a radical transformation. In any case, this organogram needs to be established to govern a structure that is not only political, social, or territorial, but even more mental and ideological. This has to do with proximity, with the conception of space and reality when it comes to the Galician idiosyncrasy, which is a world where the nearness, the village, the place, or even the municipality are constituted considering the one’s own self.10 Only in that context it was possible to perform a localized and fragmented management, lacking structuration.(Figure 2)

Source: Author’s photo

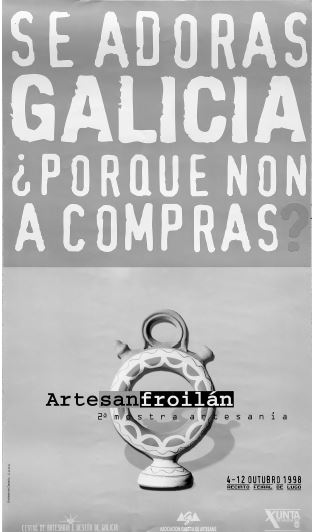

Figure 2: With the slogan “If you love Galicia, why don't you buy it?” on a piece of pottery from the workshops of Bonxe (Lugo), the identification of the country with rurality is clear

We will focus here on the specific case of the differing policies carried out by the provincial government of Lugo and the galician government (Xunta de Galicia), with the objective of attempting to illustrate the series of all kinds of transformations that led the Galician handicraft to a new symbolic dimension, when its recovery process had just started. Shortly after Manuel Fraga’s inauguration as president of the Galician government, the parlamento de Galicia (Galician parliament) adopted a law on the Galician handicraft, Lei 1/1992 de Artesanía de Galicia.11 This law established the creation of an entity called Centro Galego da Artesanía e do Deseño (Galician center for handicraft and design), in collaboration with other bodies in charge of regulating the handicraft production. Moreover, this law had a very loose legal basis that was limited to define its primary function, intended for “providing the Galician handicraft sector with the necessary professionals and specialists, through practical and non-formal vocational training”.12

At this legal starting point and considering the lack of specific provisions adopted by the autonomous community government for the development of the law or of Autonomous Community initiatives, the Provincial Government of Lugo undertook an institutional role that apparently was not up to it. This has led to a concentration of all those handicraft services that were assigned to the entity or were capable of being somehow linked to it, even partially.13 It was possible by means of the creation of two institutions from Lugo, firstly an institute for development, Instituto Lucense de Desenvolvemento (Inludes)14 and later, in 1993, another Galician center for handicraft and design, Centro de Artesanía e Deseño de Galicia (Centrad), the latter having a name that involved the whole autonomous community even though it was an entity dependent on Inludes and, therefore, belonging to a province-level administration. In fact, in the absence of other equivalent institutions, this center ended up in practice uniting all the Galician handicraft traditions within the joint hallmark of Galician cultural identity. Thus, a fusion was executed in a single scheme regarding every aspect and concept that could be associated, even in a vague and ambiguous way, with the notional field of handicraft. In this manner, Centrad was designed and established in Lugo, and it included competences in “educational, compiling and informative issues” (Freire-Paz 2004), as well as a set of non-differential provincial and autonomous community responsibilities. Centrad had an outward-looking scope of action which included transnational areas, it emerged as the heir to the Galician homeland, and it became the flagship of the provincial government of Lugo, leading to its first identity hallmark.

The structure of Centrad used to contain the scheduling of several workshops dedicated to handicraft - where the personnel in charge of technical tasks turned their attention to a series of activities as bookbinding or the elaboration of traditional regional costumes and furniture -; training courses in different handicraft disciplines - pottery, forging, textile, musical instruments, etc. -; publications focused on the study of traditional arts and crafts; participation in handicraft national and international fairs and exhibitions, and even the acquisition of important material regarding complete collections from different handicraft fields, being these collections comprised of pieces created specifically for this purpose. This way, the institution not only determines the requirements for canonically and legally determining the potential compliance with the tradition, but it also becomes a crucial link in the economic support and social recognition of the craftspeople associated with Centrad, since their institutional protection provided them with a significant source of income and, besides, it enabled them to have the prestige offered by the institutional recognition. As a direct consequence of these actions, Centrad became a catalyst for social groups, especially women and youngsters from the rural areas, who were searching for a pathway to the labor market 15 and who took advantage of these job listings emerged outside the government.

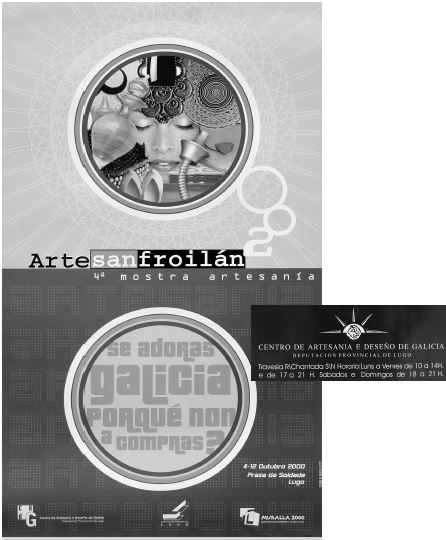

Nevertheless, what we intend to stress here, above all, is the mechanism through which Centrad became an entity in charge of disseminating iconic and symbolic values, ideologically connoted, based on concepts taken from tradition and in which the cultural products coming from handicraft become sacred pieces of identity. This is all achieved, apart from through the roles already stated above, through a series of propaganda campaigns that were widely disseminated and where the verbal and iconic messages aimed at reinforcing the distinctiveness of handicraft products and their link both with tradition and the current sociocultural reality. In short, it was about establishing several continuity links between the traditional handicraft production systems and the new ways of the recovered handicraft. This was done not only by justifying these productions through their explicit identification with the production systems from the past, but also, conversely, assigning to the new handicrafts a series of connotations through which the values associated with the handicraft tradition were finally rewritten. (Figure 3, and Figure 4)

Source: Author’s photos

Figure 3: As can be seen in the detail, the Craft and Design Center of Galicia was located in Lugo in 2000

Source: Author’s photos

Figure 4: As can be seen in the detail, the Craft and Design Center of Galicia was located in Lugo in 2000

Thus, certain negative connotations get tempered, including the ones that were remaining linked to the traditional world, which was essentially rural, both among the population staying in the countryside and, especially since the mid-20thcentury, the ones who had moved to urban or semi-urban areas. Values as scarcity, necessity, poverty, dirt, roughness, practicality, heterogeneity, etc., associated with life in traditional Galicia and, by extension, with the objects linked to this life, were replaced in the case of the new handicrafts that get inspired by the ones produced back in that context, by opposed notions as abundance, originality, singularity, identity, affectivity, homogeneity, or continuity. These values are, in any case, based on an emotional view of the past, associated with the people’s genuine and own life.

It is obvious that, both in the autonomous-political aspect and in the local-cultural side of the power exercised in Galicia by the People’s Party, the creation of a single model of collective or social individual was persecuted. This model was based on the promotion of emotional, spiritual, and sensitive values, replacing our civic, ideological, and political responsibilities. In this regard, it is natural that the messages sent both from the strictly political domain and the cultural field share that same objective. This justifies to some extent the possibility of coexistence of two parallel power orders over more than 15 years of government. For the same reason and as expected, the weakening of any of the two pillars should lead to a gradual collapse of the entire system.

This is what we consider approximately that happened when the continuing government of Manuel Fraga 16 went into crisis around 2003. It was a time when, despite winning the municipal elections, the People’s Party from Galicia, PPdG, began a certain setback that led the party to lose its absolute majority and, therefore, the government after the autonomous community elections of 2005. At the same time, already since the end of the 1990s, an open tension was clear between two internal ideological lines within PPdG. These two lines were, on the one hand, the so-called beret sector, closely related to the autonomous and pro-Galician line of Fraga and which based its power on the rural sector and was supported by that same tyrannical structure, headed by Xosé Cuíña, Francisco Cacharro and Xosé Luís Baltar; and, on the other hand, the so-called cap sector, arising from the urban and academic scope and in favor of the neoliberal and re-centralizing line defended by the national People’s Party, and headed by Xosé Manuel Romay Becaría and his candidate, Alberto Núñez Feijóo. During the ecological and economic crisis caused by the Prestige oil tanker in 2003, the beret sector was characterized by its criticism on the lack of reaction from the national government, in the hands of the People’s Party of José María Aznar. This, in the end, determined the political defenestration of the person considered as the successor of Fraga, Xosé Cuíña, and the definitive removal of the leader himself from the candidacy for the Galician government. Cuíña was replaced by the candidate who was closely related to the ideological viewpoints defended in Madrid, Alberto Núñez Feijóo, who retook power with an absolute majority in the elections of 2009 after a term in which there was a two-part government composed of a coalition between the Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) and the Galician Nationalist Bloc (BNG).

Conclusion: where were we going?

In this new political order of things, it would be obvious to think that the new ideological line installed in power tried to establish itself by displacing, eliminating, or emptying the space belonging to the beret sector. In the case we are analyzing here, this does not happen accidentally, by means of the cultural management related to handicraft. The internal political disputes within the People’s Party and the final victory of the cap sector have a very significant coincidence in time with the creation of a Galician handicraft center. This implies a de facto centralization and management of the hallmark Artesanía de Galicia (Craftmanship of Galicia) in Santiago de Compostela and, as an internal matter for the People’s Party, the institutional discard of Centrad, dependent on the provincial government of Lugo. The appointment of Feijóo as the president of the Galician People’s Party in 2006, together with the subsequent and gradual enclosing of Xosé Cuíña at the autonomous community level and of Francisco Cacharro and Xosé Luís Baltar at a provincial level, marked the start of a new era for the treatment of handicraft in terms of identity. This would be emphasized when, in 2009, PPdG obtained once again the autonomous community government with the first of several absolute majorities conferred to Feijóo.

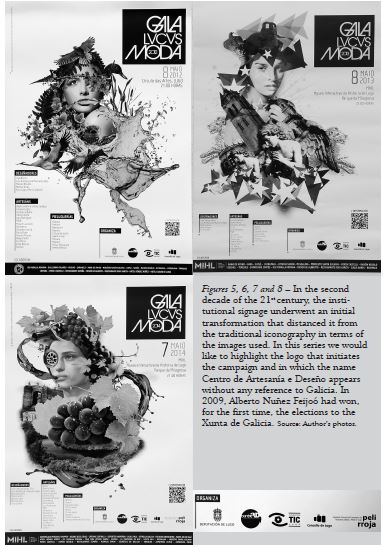

The current public entity with management capacity in the handicraft sector, Fundación Centro Galego da Artesanía e do Deseño, dependent on the Consellería de Economía, Emprego e Industria (Regional Ministry of Economy, Employment and Industry), undertakes as institutional roles the ones that, in principle, characterized the center in its previous provincial period: giving the handicraft sector the necessary infrastructure in order to carry out its training, production, commercialization and promotion programs, but particularly emphasizing the research and development applied to the elaboration techniques, product quality, design and production optimization. Therefore, progress can only be possible at the expense of what is unable to progress. Handicraft elements are then used in urban terms, with a strong minimalist influence causing the pieces to express an, largely out of context, abstract telluric symbolism, in a cosmopolitan reference framework lacking local significance. (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8)

Source: Author’s photos

Figure 5: In the second decade of the 21st century, the institutional signage underwent an initial transformation that distanced it from the traditional iconography in terms of the images used. In this series we would like to highlight the logo that initiates the campaign and in which the name Centro de Artesanía e Deseño appears without any reference to Galicia. In 2009, Alberto Nuñez Feijoó had won, for the first time, the elections to the Xunta de Galicia

Source: Author’s photos

Figure 6: In the second decade of the 21st century, the institutional signage underwent an initial transformation that distanced it from the traditional iconography in terms of the images used. In this series we would like to highlight the logo that initiates the campaign and in which the name Centro de Artesanía e Deseño appears without any reference to Galicia. In 2009, Alberto Nuñez Feijoó had won, for the first time, the elections to the Xunta de Galicia

Source: Author’s photos

Figure 7: In the second decade of the 21st century, the institutional signage underwent an initial transformation that distanced it from the traditional iconography in terms of the images used. In this series we would like to highlight the logo that initiates the campaign and in which the name Centro de Artesanía e Deseño appears without any reference to Galicia. In 2009, Alberto Nuñez Feijoó had won, for the first time, the elections to the Xunta de Galicia

Source: Author’s photos

Figure 8: In the second decade of the 21st century, the institutional signage underwent an initial transformation that distanced it from the traditional iconography in terms of the images used. In this series we would like to highlight the logo that initiates the campaign and in which the name Centro de Artesanía e Deseño appears without any reference to Galicia. In 2009, Alberto Nuñez Feijoó had won, for the first time, the elections to the Xunta de Galicia

We could symbolize the process of ideological restructuring regarding the Galician handicraft as a gradual hearing impairment with an emptying being executed in successive layers. In the closing of the traditional stage around the 1960s we identify the voice silence, in the sense that a first multiple rupture is produced in the body of handicraft. This way, the gap between place and time generated a space for the simulation of the memory that no longer emerges from the intersection between the experience of the past and the perspective of the future: handicraft as being. After this first rupture, like a background radiation, we can still feel the sound of rumors, the vibration, the tribal tom-tom as the evocative residual of the voice it used to be, still keeping the original ability of containing an identity that becomes a collective question of faith, but without a syntax capable of including the parts of the whole, thrown irremediably to an entropic scattering: handicraft as having. Finally, about the current phase, we would consider that the only remnant of that original voice, sublimated until its complete incorporeity is achieved, is a vaguely perceptible echo. It is only the sound of its own rupture, too distant already from the primitive tactile perceptions of the traditional phase, but still present as an invitation to the recipient during the recovering period. These perceptions are now replaced by a visual impact that is always, by definition, immediate, evanescent, and fragmentary: handicraft as seeming.