Visual approaches have not been systematically employed in the study of contemporary borders despite their affordances in bringing to the fore individual perspectives and experiences (Kudžmaité and Pauwels 2020; Ball 2014).1 Drawing on the concept of borderscapes, whose plasticity and inherent aesthetic nature stimulates an exploration of diverse border universes (dell’Agnese and Szary 2015), this visual essay interrogates routiers’ border(ing) enactments and contingent meanings.2

Routier is the self-designation employed by Senegalese men driving heavily laden, aging vehicles from Europe into Africa. This perilous journey takes them through Morocco, the Western Sahara occupied territories, Mauritania, and finally to their destination in Senegal. Some even beyond. The vehicles used by routiers are eventually sold and integrated into regional transportation systems. In Senegal, popular models include the Peugeot 504/505, older versions of the Renault Trafic, Volkswagen Golf, and Toyota Hiace. During their journey and upon arrival, routiers deliver money remittances and personal belongings. They also barter and trade diverse goods, mostly second-hand objects, some of which in need of repair: clothing, household appliances, toys, spare parts, rice, cosmetics. Not only do the vehicles they travel in regain value as they move south, but even items that are considered obsolete or even waste in Europe gradually become valuable (Neto and Falcão 2022).

Being a routier entails seeing like a routier in its constant, mutual entanglement of diverse power relations and types of agency to undermine the states’ quest for legibility (cf.Scott 1998). This means challenging the ways in which states, through technocratic management, attempt to see - categorize, organize and control - their subjects and other individuals who traverse their territories.

Seeing like a routier means being constantly vigilant and poised to take advantage of opportunities. It involves anticipating encounters with police and military checkpoints, armed groups and robbers, as well as regularly scanning the road ahead for potential obstacles, such as camels, potholes, and car accidents. An experienced routier effectively handles mechanical failures by being vigilant for places of refuge, friendly car workshops, gas stations, and roadside items that could prove useful. It involves either engaging in bribing or proactively seeking road traffic fines (often due to overloading) based on the number of checkpoints and the types of inspections anticipated.

Knowledge and skill are crucial for routiers who must navigate a complex array of sometimes overlapping politico-administrative, socio-economic, cultural and geographical borders. To successfully navigate these terrains they rely on and are part and parcel of a complex and flickering web of actors, including entrepreneurs, mechanics, police officers, military personnel, custom officials, and migrants heading north. Together, these actors form an “infrastructure of people” (Simone 2004) that articulates the flow of goods, money, people, and information (see Vammen 2022) while simultaneously shaping and giving meaning to a unique set of borderscapes.

The term borderscapes garnered currency after Rajaram and Grundy-Warr’s (2007) piece which, following Lefebvre (1991), sustained the potential of the term in exploring “alternative ways of visualising space and society” in its relation to (inter)national borders (Rajaram and Grundy-Warr 2007: xxiv). According to the authors, the borderscape is a “zone of varied and differentiated encounters”; of competing and even contradictory emplacements and temporalities’ and points to “hidden geographies and insurrectionary political forms that question the territorial restriction on justice and belonging” (Rajaram and Grundy-Warr 2007: xxx). Ever since, the concept has been used interchangeably with related notions such as borderlands, borders and the adjacent territories. The borderscape has been also employed to think about externalisation as it questions borders as located lines (Celata and Coletti 2019); about artistic and symbolic bordering practices (Schimanski 2015); or to consider aesthetic features of the border landscape (dell’Agnese and Szary 2015) as it evokes visual and personal dimensions in its construction, perception and purpose (cf.Cosgrove 1985). We find especially relevant how the term borderscape has been expanded to address borders from a phenomenological perspective, stressing the need to focus on experiences and representations (Brambilla 2015). Far from mutually exclusive definitions, Krichker (2021) proposes that we think about the borderscape as a “panorama” that seeks to grasp the complexity of border(ing) phenomena in its relation to space, imagination and experience.

Below, we present ten captioned images that depict and explore the borderscapes of routiers as they perceive, imagine, and experience the multitude of borders in which their livelihoods are embedded. Selected still images stem from audiovisual materials collected between 2017 and 2019 during ethnographic fieldwork and the filming of a documentary among Senegalese routiers.3 Our research included extensive fieldwork in Lisbon and Dakar, as well as two ten-day journeys from Portugal to Senegal, travelling in late 1980s Peugeots 504s with the same seasoned routier: Mbaye Sow, who is now 63 years old. However, since pandemic restrictions were introduced in early 2020, most of this activity has disappeared, and the actors who once participated in it have either moved elsewhere or had to find other means of making a living. This is not to say that the flow of goods came to a halt, only that it has found other trajectories, from individual carriage by plane or bus to container shipping.

The routiers’ universe configures a mobile border zone from where “new objects and understandings [of migration] come into view” (Walters 2015: 15; cf.Konrad 2015; Dijstelbloem 2021). Through an examination of routier activity, we not only interrogate the broader implications of the border moments and events captured in the images presented here, but also, in attempting to see like one of them, we necessarily challenge the “invisibility of its content” (Berger 2013). Routiers, with their routes and vehicles, provide a unique perspective for studying mobility within mobility and borders within borders. Through their experiences, we witness how borders shape the lives and travels of routiers and we can peer into the flows and materiality of specific objects, which despite the excess of control are, in the end, mere day-to-day objects. Indeed, by exploring routiers borderscapes, which encompass more than just international borders, we gain insight into the economic, cultural and social values and meanings of this universe. The result is a constellation of more or less singular perspectives that feed an on-going debate not only on how to visually represent borders writ large (Kudžmaitė and Pauwels 2020), but also on how certain groups of people embody (Mbembe 2019; Agier 2016), see and are seen by those very borders (Ball 2014; M’Charek 2020; Plájás, M’Charek and Baar 2019). Ultimately, our exploration is an invitation for the reader/viewer to embark on a journey of discovery.

A Senegalese enclave

The Senegalese workshops in Reboleira, a parish of Amadora in the outskirts of Lisbon, are located along a short segment of a former military road. In the mid-2000s, following the violent clearance of an existing informal neighbourhood, routiers seized the opportunity to set up their open-air car workshops in the area.

Today, Reboleira has become a hub for West African migrants, and a variety of negotiations occur between routiers and other actors involved in the used-car and spare parts trade, transportation logistics, and paperwork facilitation for cars to circulate outside of Europe.

The workshops in Reboleira, much like those in Senegal, are characterized by their makeshift and complex socio-cultural nature, which defies Western spatial and legal principles. It can be challenging to determine the differences between the two due to their unique circumstances, thus questioning their true socio-cultural location.

Border lexicon

This image depicts the road entering Rosal de la Frontera, located approximately 4 km away from the official border between Portugal and Spain. The only elements that acknowledge the existence of an international border are the road signposting and the border-lexicon applied to localities. Border checkpoints were dismantled in the mid-1990s following the implementation of the Schengen Agreement, and nowadays, there is virtually no control or surveillance, at least at the gateways and moments of crossing well identified by routiers. For them, this is essentially an economic frontier, which they master well, strategically juggling with the differential cost of things, particularly in terms of fuel, which is more affordable on the Spanish side.

Across the straight

Some 11.000 nautical miles (20 km) separate the ports of Algeciras (Spain) from Tanger Med (Morocco). While crossing the border, passengers line up in the ferryboat’s lounge to go through the performative task of passport stamping (Parker and Vaughan-Williams 2012) by Moroccan customs officials at an improvised desk-border-post. For routiers, crossing this border means that while obstacles may not suddenly disappear upon entering “Africa”, things can be more easily managed, and the relative value of the vehicles and goods carried automatically increases.

This border, which may not necessarily be crossed at its official demarcation, marks more than a simple line between Spain and Morocco. It also represents the separation and connection between Europe and Africa, the Global North and the Global South, and with it, a differential value of things, goods, and labor (Balibar 2002; Mezzadra and Nielson 2013). The relative value of documents also changes as European passports lose their value compared to West African ones. Ultimately, the success and viability of the routier activity heavily relies on playing with the setbacks and advantages provided by borders.

Mnemonic border

The unknown and occult, fear, and landscape elements but also mountain ranges, rivers, forests, have represented - and still represent - some of the foundational and empirical arguments at the origin of many border demarcations and imaginaries throughout history.

The westernmost stretch of the High Atlas Mountain range near Agadir is among the most dangerous segments. This is not only a physical element that separates the arid, rocky and hot southern plains from the more fertile and milder northern coastline region. For routiers, it serves as a mental and mechanical border. The difficult terrain poses challenges for vehicles, and the lack of support in case of accidents adds to the anxiety. Overheating, gear and brake issues are frequent. There are only a handful of stations and towns, which are far apart, to provide support in case needed. Hidden border(ing) dimensions are experienced through the mnemonic features of the landscape, such as steep slopes, loose rocks, long tunnels, as well as a certain curve where something traumatic has happened (cf.Neto 2017). Elements as such recall past events and feed present fears, while contributing to the consolidation of this stretch of road as an idiosyncratic borderscape.

Invisible lines

In the near horizon lies the borderline between Morocco and Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony known for its rich fishing and phosphate resources. That rectilinear imaginary line, which we cannot see but only grasp through other elements, shall remain invisible inasmuch Moroccan sovereignty is not called into question. Subtler aspects inform about the status and plight of this territory. As routiers move into Western Sahara occupied territories’, urban settlements gradually fade away, and the distances in between grow larger.

Following annexation, in 1975, many Saharawi communities fled to the Algerian refugee camps. Militarization is evinced by the presence of UN vehicles, military convoys, makeshift police checkpoints, random regular passport control and cargo inspection. Night travelling thus becomes increasingly risky for travellers, not only because of the lack of assistance in case of breakdown, but also due to the fragile security situation.

Border soundscapes

At the Morocco-Guerguerat strip border post, a huge, ten-meter tall scanner analyses vehicles. As German shepherds sniff cars, border police hassles travellers by randomly selecting pieces of luggage for inspection. For most the ordeal often ends in bribery. But it is not unusual that others, feeling that inspections will end badly, decide to simply flee.

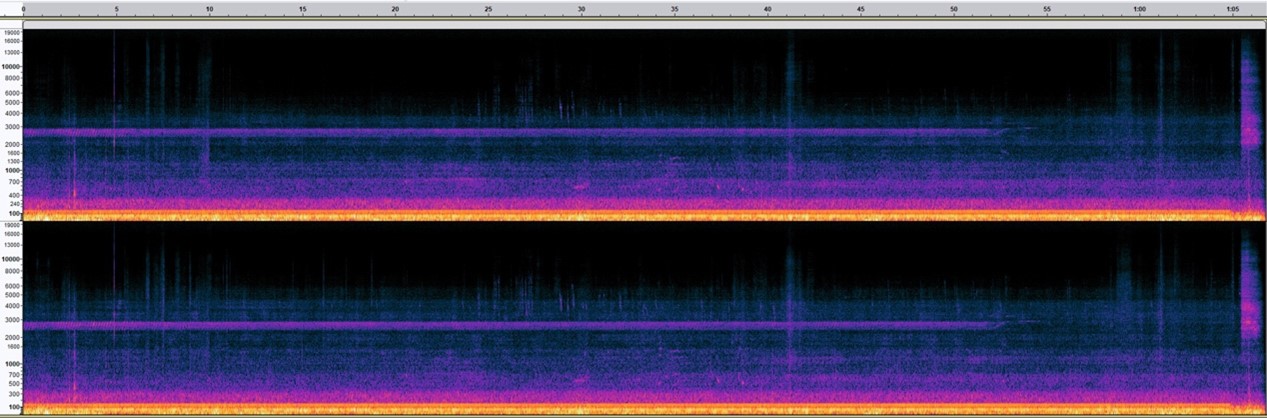

The straight horizontal line of the spectrogram (first 53 seconds) depicts the sound emanating from the scanner: a humming noise mixed with a warning siren that is repeated in short cycles. The humming low noise is interrupted (final seconds) by a hissing sound from the release of a truck’s air brake, now ready to move forward. Indifferent to the geopolitical limit, birds fly and sing continuously across the arid and littered landscape.

Where highly militarized border posts cannot be photographed, sound becomes a way of feeling and seeing (cf.Helmreich 2015: xix). An excerpt of the soundscape, translated in the form of a sound spectrogram, is the possible glimpse onto this border.

“Kandahar”

A cemetery of vehicles grows by the day in the roughly 5 km of the Guerguerat buffer zone between Morocco and Mauritania border posts. Polisario Front freedom fighters and a UN peacekeeping mission monitor every movement. The territory remains heavily mined. Routiers and other drivers strive to avoid deviating from the established tire tracks. Most carcasses account for people and cars unable to (re)enter Morocco or Mauritania. Overloading of cargo and mechanical problems, compounded by the poor conditions of the section of the road, often determine an endpoint of the journey. Stranded vehicles are then dismantled and sold in the trade of spare parts (Drury 2019). Safe harbours - that is, the social relationships built by routiers (cf.Simone 2004) - are crucial for the successful crossing of this dangerous and unpredictable geography, which earned its nickname: “Kandahar”.

Travelling border

Permits, known as passe-avants, are required for crossing Mauritania and are often informally handled outside of the border post to avoid further checking. However, drivers are only allowed to leave the border premises closer to dusk, following the departure of a police convoy that carries the original documents, including passports and car documents, to the southern border post of Rosso Mauritania-Rosso Senegal. This practice ensures that travellers have a maximum of 24 hours to leave the country and that drivers do not divert off the main road.

Despite having permits to cross, routiers face around 20 roadblocks on their journey through Mauritania. At these checkpoints, various security forces inspect their passports, check the condition of their vehicles, and scrutinize their cargo. Forced to drive through the night, routiers become exhausted and vulnerable, making them less equipped to negotiate bribes and “gifts”. In this sense, Mauritania is an immense borderland - or a borderline, of some 650 km thick. Although control is tougher along the mapped routes, it is also true that unexpected situations and dangers may still lurk away from these paths. The road is the routiers’ own country. Beyond the roadside lies the unknown, an immense uncharted territory.

Border twins

Between the twin border towns of Rosso-Mauritania and Rosso-Senegal, a smoky barge ferries cars, trucks, people and goods across the river Senegal. Locals cross freely without any form of control. This sudden in-betweenness of the river as a border provides an unique opportunity to capture images.

Routiers often leave their vehicles in line for the crossing and take a small pirogue to the other side to expedite paperwork. As a result, the official entry of vehicles into Senegal often precedes their physical arrival.

The border within

Mbaye Sow negotiated for extra time to meet a police officer responsible for overseeing the convoy of routiers travelling from Rosso-Senegal to Gambia. They have a tight schedule, as they must deliver packages and display their vehicles to potential buyers before returning to their homes in Senegal. It is worth noting that according to Senegalese law, vehicles older than eight years are not allowed to remain but only to traverse the country. However, this does not prevent the routiers’ networks from finding alternative ways to re-enter Senegal.

Despite their resilience, routiers constantly feel like foreigners no matter where they go. Senegalese migrants living in Europe are object of diverse social pressures to redistribute their supposed wealth among their peers, but also with corrupt authorities once in their country of origin. Be it in Europe or in West Africa, routiers embody the frontier (Mbembe 2019; Agier 2016; Konrad 2015), a shifting, mobile frontier that remains within them.

The missing picture

In early 2020, the routier activity came to a halt due to the restrictions imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic, which led to the closure of international borders. Since then, most routiers have sought alternative sources of income in Europe or Senegal. Mbaye Sow, for instance, first migrated to France to work as a fruit picker, then moved on to Germany to work in an Amazon sorting facility, before eventually returning to Portugal to work on a construction site in Lisbon.

Although land borders have since reopened, most of the routiers we met did not return to Reboleira.