People strive to attain positive self-views (self-enhancement) and avoid negative ones (self-protection) when they process self-relevant information. According to Sedikides and Strube (1997), this effort is a part of the self-evaluation process, which has a motivational basis and includes particular motives (i.e., self-enhancement, self-verification, self-assessment, and self-improvement). Sedikides (2007) proposed that self-enhancement and self-protection are the strongest ones among self-evaluation motives. Accordingly, self-enhancement is related to attempts to maintain self-view positivity; whereas self-protection is linked to defending self-views against negative self-relevant information (Alicke & Sedikides, 2009; Baumeister, 1998; Sedikides & Gregg, 2003). Self-enhancement and self-protection motives play a role in increasing self-regard or at least preventing its decrease (Alicke & Sedikides, 2009). Moreover, attempts to sustain the positivity of self-concept are also important in terms of self-integrity (Campbell & Sedikides, 1999).

Although some researchers have proposed that self-enhancement includes self-protective strivings or self-deception processes (Baumeister, 1998; Sedikides & Strube, 1997), some others have efficiently distinguished self-enhancement from self-protection, defining these as valuation motives (Sedikides, 2007; Sedikides et al., 2004). The current work suggests that self-enhancement can be distinguished from self-protection in terms of optimal human functioning. In order to explain the nature of these two motives, basic psychological needs (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness; Deci & Ryan, 2000) posited by Self-Determination Theory can be used as a framework. In addition, relying on previous research, examining their associations with psychological adjustment (i.e., contingent self-esteem, global self-esteem, and intolerance of uncertainty) can expand our understanding of the distinction between these motives.

It seems critical to comprehend the adaptive nature of valuation motives based on basic need satisfaction and psychological adjustment, especially in today’s young adults. Because it is argued that young adults - the so called ‘generation me’ - seem to have higher self-esteem and a greater tendency to self-enhance when compared to previous generations (Twenge, 2014). This study, therefore, attempts to provide deeper insight on understanding the self-evaluation processes (i.e., self-enhancement and self-protection) related to basic need satisfaction and psychological adjustment in the younger generation. Below, self-enhancement and self-protection motives are conceptually described before mentioning the potential associations of valuation motives with basic need satisfaction and particular individual differences that indicate psychological adjustment.

Valuation Motives: Self-Enhancement and Self-Protection

People use a broad range of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral strategies (e.g., self-handicapping, self-serving bias, unrealistic optimism, the illusion of control, the above-average effect, and strategic social comparisons) to self-enhance or self-protect (for a review, see Sedikides and Gregg, 2003). Although most researchers have studied these strategies separately, Hepper et al. (2010) analyzed a variety of these strategies together by generating a self-report measurement. They examined self-enhancement and self-protection strategies as individual differences and demonstrated that self-enhancing and self-protective tendencies are differently associated with some personality traits.

Moreover, self-evaluation processes can be considered generation-based characteristics. Twenge (2014) argues that today’s young adults tend to have higher self-esteem and positive self-views, be more self-focused, and even more narcissistic due to cultural changes highlighting individualism and positive self-regard. Recent research also provides evidence for generation differences in personality and self-relevant processes (e.g., Gentile et al., 2010; Twenge & Campbell, 2008; Twenge et al., 2012; Twenge & Foster, 2008). For example, Twenge and her colleagues (2012) demonstrated that compared to previous generations, young adults tend to evaluate themselves as above average on agentic characteristics such as self-confidence, academic ability, drive to achieve, writing ability, and leadership apart from changes, actual performance and increased effort; although recent research has also indicated that the self-enhancement motive seems not to change across generations (Trzesniewski et al., 2008). Despite these explanations providing a new viewpoint toward the self-evaluation process in young people in terms of generational differences, it can be considered that there is still a need to look deeply into the adaptiveness of the valuation motives with the emphasis on the differences between them. Thus, self-enhancement and self-protection motives that help to reach a positive self-view can be considered as a characteristic of the younger generation. These motives can be traced in terms of basic need satisfaction and psychological adjustment, as well as self-esteem.

Valuation motives provide some benefits for human functioning (Sedikides, 2007; Sedikides & Luke, 2007; Taylor & Brown, 1988); these motives are universal and have an adaptive nature (Sedikides et al., 2003; 2004). For instance, Taylor et al. (2003) demonstrated that self-enhancement is positively related to mental health (e.g., autonomy, personal growth, self-acceptance, and positive relations), and psychological resources (e.g., optimism, self-esteem, mastery, and positive reframing); but negatively related to mental distress such as depression, anxiety, and hostility. In a similar vein, Kurman and Eshel (1998) demonstrated that self-enhancement is positively linked to emotional adjustment (i.e., self-esteem, sense of well-being, and stress reaction). Recent studies also show that self-enhancement increases psychological well-being in both the U.S. and China samples, which means that this relation holds independently of cultural context (O’Mara et al., 2012).

Recent research on self-protection shows some inconsistent findings with the adaptive nature of valuation motives. For example, Johnson et al. (1997) demonstrated that self-protection (i.e., self-deception) predicted both worse problem solving and higher hostility. Lei and Duan (2016) also indicated that self-protection was negatively associated with psychological health. Another study investigated the costs of self-protection conceptualized as self-handicapping and showed its associations with negative mood, substance use, decreases in intrinsic motivation and competence satisfaction (Zuckerman & Tsai, 2005). Moreover, self-control (Uysal & Knee, 2012) and self-compassion (Akın & Akın, 2015) seem to be negatively associated with self-protection (i.e., self-handicapping). Similarly, Petersen (2014) suggested that self-compassion decreases the use of self-protective strategies, since it leads people to have unbiased and realistic self-views.

Despite this claim for the adaptiveness of self-enhancement and self-protection, some research findings imply that these motives would be maladaptive as well. As mentioned above, self-protection motive seems to be associated with some negative indicators of maladjustment. Similarly, Robins and Beer (2001) argued that long-term consequences of self-enhancing biases seem maladaptive, while seeming adaptive in the short-term. Research by Colvin et al. (1995) also indicates that self-enhancement is associated with poor social skills and psychological maladjustment not only in the short-term (laboratory setting) but also in the long-term context. To sum up, it seems that there is a controversy regarding the adaptive nature of self-enhancement and self-protection. To shed light on this debate, basic psychological needs explained by Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 2000) can serve as a framework, since they are essential for optimal human functioning.

Basic Need Satisfaction and Valuation Motives

SDT is a widely used theory to study basic psychological needs, motivation, and well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2000). This theory posits that autonomy, competence, and relatedness are the basic psychological needs that are innate and universal. Autonomy refers to the need for volition and self-endorsement. The need for competence, on the other hand, is related to feeling effective while interacting with the social environment (Deci & Ryan 2000; White, 1959). Finally, relatedness refers to the need for experiencing intimacy and love in relationships with significant others (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Deci & Ryan, 2000). The satisfaction of these needs has an essential role in attaining well-being, integrity, and psychological growth. Yet, the thwarting of them can bring on defensive or self-protective processes (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Similarly, Vansteenkiste and Ryan (2013) suggest that the frustration of basic psychological needs might make people predisposed to defensiveness, aggressiveness, and ill-being.

From the SDT perspective, to understand when and under what circumstances defensive processes can emerge, many studies have provided empirical data for the explanations of defensiveness. For example, Hodgins et al. (2006) indicated that when autonomy orientation was primed, participants reported lower defensiveness, but better performance. Knee and Zuckerman (1996) also provided evidence suggesting that individuals who have high autonomy but low control orientation reported less self-serving biases after failure feedback. They argued that because individuals who are more autonomous, but less control-oriented, perceive failure feedback as less threatening to self-esteem, and interpret it as an opportunity for growth. Hence, these individuals tend to display less self-serving biases. Similarly, Lynch and O’Mara (2015) found that autonomy orientation is positively linked to approach-oriented self-enhancement. However, it is negatively related to avoidance-oriented self-enhancement (i.e., defensiveness). Moreover, approach-oriented self-enhancing strategies mediate the relationship between autonomy orientation and psychological well-being.

To sum up, these research findings support the notion that the SDT presents a useful framework to understand defensive processes by focusing on autonomy orientation. Nevertheless, as an essential determinant of optimal human functioning, the satisfaction of basic psychological needs has not been examined yet to our knowledge. The main objective of the current study is to explore whether the satisfaction of basic psychological needs could contribute to understanding not only self-protection (i.e., defensiveness) but also self-enhancement motives. Moreover, Deci and Ryan (2000) argue that although the satisfaction of each basic need is essential for psychological health, the fulfillment of one or two needs is not sufficient for optimal human functioning that actually requires the satisfaction of all three psychological needs. Recent research also supports this notion by evaluating overall need satisfaction (e.g., Bégin et al., 2018; Campbell et al., 2018; Deci et al., 2001; Mackenzie et al., 2018; Uysal et al., 2010; Vandenkerckhove et al., 2019). This study has, therefore, adopted a similar notion while examining the associations of overall need satisfaction with the valuation motives.

Psychological Adjustment and Valuation Motives

The foregoing discussion on the adaptive nature of self-enhancement and self-protection illustrates that examining the associations between these motives and different indicators of psychological adjustment may contribute to clarify the theoretical distinction in between. On that account, in addition to basic psychological needs, roles of contingent self-esteem, global self-esteem, and intolerance of uncertainty are examined as indicators of psychological adjustment.

Many studies indicate that using the strategies of self-enhancement and self-protection is closely related to the level of self-esteem (Baumeister et al., 1989; Hepper et al., 2010; Kernis et al., 2008; Tice, 1991). For instance, Hepper et al. (2010) has found that self-enhancement is positively associated with self-esteem, whereas self-protection is negatively associated with it. Another study also indicates that verbal defensiveness is negatively associated with global and implicit self-esteem, while it is positively linked to unstable and contingent aspects of self-esteem (Kernis et al., 2008).

In the current study, it is predicted that, as an aspect of fragile and unstable self-esteem (Deci & Ryan, 1995), contingent self-esteem might have a different relationship with each valuation motive. Contingent self-esteem is defined as positive or negative feelings about oneself depending upon meeting evaluative standards and matching self-expectations and others’ expectations (Deci & Ryan, 1995; Kernis, 2003). Deci and Ryan (1995) argued that people with high contingent self-esteem are likely to use defensive processes to avoid a decrease in self-worth when they are confronted with self-threatening information. Consistent with this view, examining not only global self-esteem but also contingent self-esteem might be helpful to distinguish self-enhancement from self-protection. People with high contingent self-esteem might use self-protective strategies over self-enhancing ones, since they are preoccupied with avoiding the decrease in self-worth instead of promoting the increase in it.

From the viewpoint of optimal human functioning, self-enhancement and self-protection might have different relationships with intolerance of uncertainty, which refers to a tendency to respond to uncertain situations and events in a negative emotional, cognitive, and behavioral way (Dugas et al., 2004), or more briefly, a predisposition to fear of the unknown (Carleton, 2012). Recent research reveals that intolerance of uncertainty is linked to mental health evaluated as worry, anxiety, and depression (e.g., Boelen & Reijntjes, 2009; Buhr & Dugas, 2006; McEvoy & Mahoney, 2011). In this respect, the tendency could also be interpreted as a negative indicator of psychological adjustment. Besides, intolerance of uncertainty could contribute to clarifying the distinction between self-enhancement and self-protection. This study claims that the more individuals become intolerant of uncertainty, the more they tend to use self-protective strategies rather than self-enhancing ones. Because these individuals interpret self-related uncertain situations or events more threatening to self-esteem, they may behave defensively against possible unknown self-threats to their self-esteem.

To sum up, previous studies have shown contradictory findings on the adaptive nature of self-enhancement and self-protection (e.g., Colvin et al., 1995; Lei & Duan, 2016; O’Mara et al., 2012; Robins & Beer, 2001; Taylor et al., 2003). The distinction between these motives is less clear, but it seems that it is essential to evaluate the adaptiveness of these motives. As Alicke and Sedikides (2009) imply that understanding these motives could contribute to explaining human behavior and judgment, clarifying the distinction between self-enhancement and self-protection could expand our understanding about not only the motivational aspects of the self in social psychology but also different social psychological phenomena, such as interpersonal relationships (Hoorens, 2011; Schütz & Tice, 1997; Wood & Forest, 2011) or prejudice and discrimination (Fein & Spencer, 1997; Major & Eliezer, 2011). Furthermore, the distinction between valuation motives could also be taken into consideration while accounting for work motivation (Korman, 2001; Mitchell et al., 2018), academic performance (Blanton et al., 1999; Gramzow et al., 2014) or mental health (Alloy et al., 2011; Lei & Duan, 2016; O’Mara et al., 2012; Taylor et al., 2003).

As well as investigating the difference between the valuation motives on the basis of their adaptive nature, it also seems important to evaluate their adaptiveness by studying young adults. Because today’s young people, defined as ‘generation me’, are assumed to have more self-confidence, egocentrism, and even more narcissism due to cultural shift encouraging individualism and self-esteem (Twenge, 2014). They also tend to evaluate themselves as above average, regardless of their actual performance or effort, more than previous generations (Twenge et al., 2012). For this reason, it can be thought that providing deeper insight on the functions of valuation motives, based on their associations with basic need satisfaction and psychological adjustment, becomes more important for the possible intervention attempts supporting the self-esteem of young adults.

Taking into account the previous evidence that points out that there is a contradiction in adaptiveness of valuation motives (e.g., Colvin et al., 1995; Lei & Duan, 2016; O’Mara et al., 2012; Robins & Beer, 2001; Taylor et al., 2003), examining the contribution of optimal human functioning and psychological adjustment can be helpful, while distinguishing between these motives. Hence, the current study aims to distinguish self-enhancement from self-protection in terms of their associates representing optimal human functioning, including the satisfaction of basic psychological needs and the indicators of psychological adjustment (i.e., contingent self-esteem, global self-esteem, and intolerance of uncertainty). More specifically, if these motives are differentiated in terms of adaptiveness, self-enhancement - serving routinely to acquire the desired self-view - would be positively associated with basic need satisfaction and global self-esteem, and negatively related to contingent self-esteem and intolerance of uncertainty. In contrast, self-protection, which is triggered by a self-threat and requires concern for a decrease in self-worth, would be positively associated with contingent self-esteem and intolerance of uncertainty, whereas negatively associated with basic need satisfaction and global self-esteem.

Method

Participants

Data was collected from 531 undergraduates from four different public (n = 275) and private (n = 256) universities in Turkey. Participants were selected through convenience sampling, and they took extra course credits in exchange for their participation. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 26 years (365 female and 166 male; M age = 21.16, SD = 1.54).

Regarding the socioeconomic status (SES) of the sample: 16.4% of the participants (n = 87) were from lower SES, 36.3% of them (n = 193) were from lower-middle SES, 33.5% (n = 178) upper-middle SES, and 13.8% (n = 73) were from upper SES. Furthermore, participants reported their mothers’ education levels as less than high school (40.9%), high school (32.8%), and college or graduate school (26.3%). They also reported their fathers’ education as less than high school (36.0%), high school (34.6%), and college or graduate school (29.4%).

Measures

Strategies of Self-Enhancement and Self-Protection.The Self-Enhancement and Self-Protection Strategies Scale was developed by Hepper et al. (2010) to assess the tendencies of self-enhancement and self-protection. The original scale consists of 40 positively worded items identifying the strategies of self-enhancement and self-protection motives (e.g., “When you do poorly at something or get bad grades, thinking it was due to bad luck”, “When you do poorly at something, reminding yourself of your other strengths and abilities”, “Believing that you are changing, growing, and improving as a person more than other people are”). The scale has a four-factor structure (i.e., positivity embracement, favorable construals, self-affirming reflections, and defensiveness). All items are rated on a 6-point Likert Scale (1 = not at all characteristic of me, 6 = very characteristic of me).

The scale was adapted into Turkish by Yildirim (2015). The Turkish version of the scale contains 34 items and two dimensions that represent sets of strategies of self-enhancement and self-protection. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for self-enhancement and self-protection subscales were reported as .73 (re-test reliability, r = .75) and .82 (re-test reliability, r = .70), respectively. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for self-enhancement and self-protection subscales were found as .76 and .89, respectively.

Basic need satisfaction. Basic Psychological Needs Scale-Revised was administered to assess the satisfaction of basic psychological needs. This 26-item scale was generated by Yildirim (2015) on the basis of different measures of need satisfaction (Gagne, 2003; Sheldon & Hilpert, 2012) by including culture-specific items. The scale contains eleven items for relatedness (e.g., “I really like the people I interact with”), nine items for competence (e.g., “Most days I feel a sense of accomplishment from what I do”), and six items for autonomy (e.g., “I feel like I am free to decide for myself how to live my life”). All items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 7 (definitely true). Yildirim (2015) reported Cronbach’s alpha for the whole scale as .91. Furthermore, it was also reported that the alpha coefficients for autonomy, competence, and relatedness were .88, .87, and .86, respectively. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .93. This coefficient for autonomy, competence, and relatedness was found as .88, .86, and .88, respectively. Because the importance of overall need satisfaction for optimal human functioning is emphasized (Deci & Ryan, 2000), in this study, the total score of the basic need satisfaction measure was calculated.

Global Self-Esteem. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale developed by Rosenberg (1965) was administered to assess the global level of self-worth. This measure consists of 10 items (e.g., “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”, “All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure”) with a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Five of the items are reverse coded. This scale was adapted to Turkish by Çuhadaroğlu (1986) and Cronbach’s alpha was reported as .90. The alpha coefficient in this study was .86.

Contingent Self-Esteem. The Contingent Self-Esteem Scale developed by Paradise and Kernis (1999) was administered to measure the extent to which individuals’ self-esteem depends on meeting standards, performance outcomes, and evaluations by others (as cited in Kernis & Goldman, 2006, p. 77). This measure is a 15-item scale with five reverse coded items (e.g., “An important measure of my worth is how competently I perform”, “Even in the face of rejection, my feelings of self-worth remain unaffected”) rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all like me, 5 = very much like me). Cronbach’s alpha for the original scale was .85 (re-test reliability, r = .77). Çiffiliz and Abayhan (2009) translated the scale into Turkish and found the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients as .86. Here, Cronbach’s alpha was .81.

Intolerance of Uncertainty. The Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (Buhr & Dugas, 2002) was used to evaluate the extent to which individuals believe that uncertainty or unpredictability is acceptable. It contains 27 items (e.g., “Uncertainty makes me uneasy, anxious, or stressed”, “I must get away from all uncertain situations”) with a scale ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic of me) to 5 (entirely characteristic of me). This measure was translated into Turkish by Sarı and Dağ (2009) from the English version of the scale (Buhr & Dugas, 2002). The researchers removed only one item as a result of the exploratory factor analysis. Hence, the Turkish version of the scale consists of 26 items and its Cronbach’s alpha was found as .79 (Sarı & Dağ, 2009). In the current study, the alpha coefficient was .95.

Procedure

Firstly, the ethic approval for the study was obtained from Hacettepe University Ethics Commission. In the data collection process, after participants were informed about the aim of the study and the procedure via informed consent, they completed the questionnaires in paper-pencil format. Participants spent approximately 30-40 minutes on the measures.

Data Analysis

In order to examine the differences in the variables of interest in demographic terms (i.e., gender, age, socioeconomic status, educational sector, mothers’ education, and fathers’ education), independent sample t-tests and ANOVAs were conducted. Bivariate and partial correlations among variables of interest (i.e., self-enhancement, self-protection, basic need satisfaction, global self-esteem, contingent self-esteem, and intolerance of uncertainty) were also performed. Hierarchical regression analyses were computed in order to examine the predictors of self-enhancement and self-protection.

Results

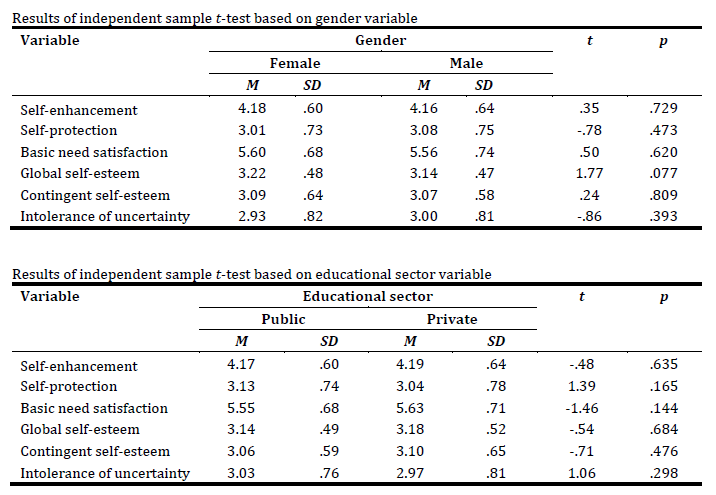

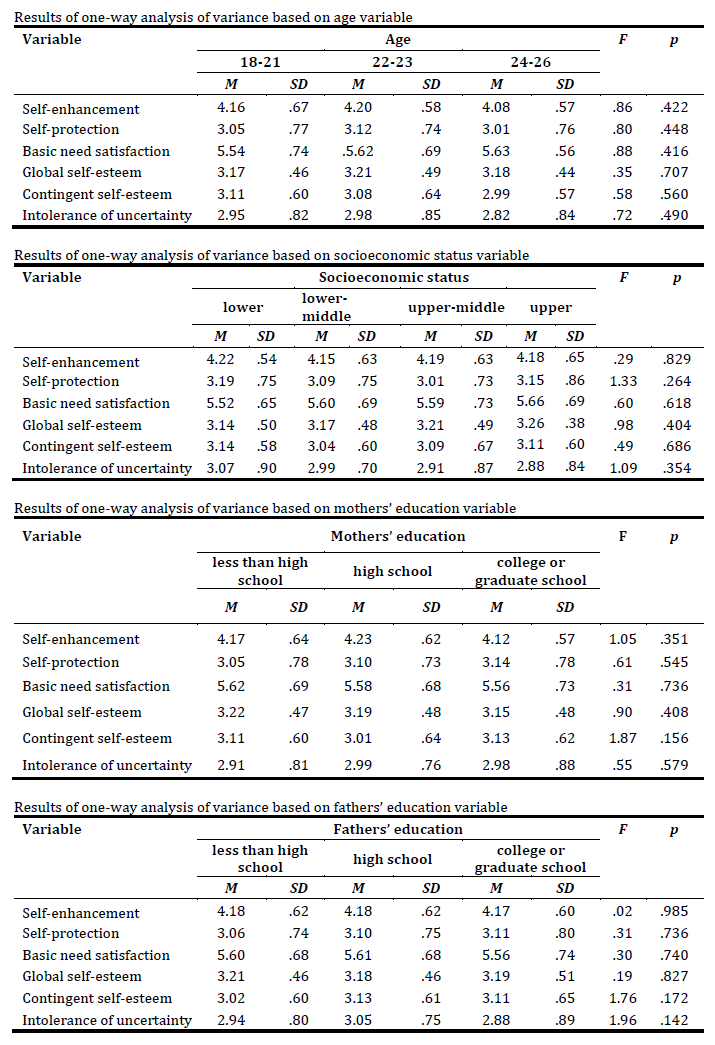

Preliminary analyses were performed to examine the potential demographic differences for the variables of interest (i.e., self-enhancement, self-protection, basic need satisfaction, global self-esteem, contingent self-esteem, and intolerance of uncertainty). Independent sample t-tests demonstrated that there were no significant gender and educational sector (public vs. private university) differences for these variables (Appendix A). ANOVA analyses also revealed that the demographic variables of age, socioeconomic status, mothers’ education, fathers’ education were unrelated to major variables of the current study (Appendix B).

Correlations among variables

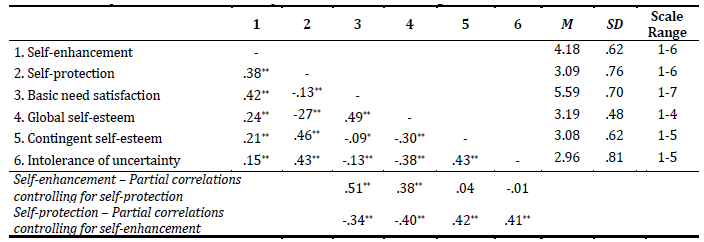

The aim of the current study was to distinguish self-enhancement from self-protection in terms of their associations with need satisfaction as well as positive (global self-esteem) and negative (contingent self-esteem and intolerance of uncertainty) indicators of psychological adjustment. It was expected that self-enhancement would be positively related to basic need satisfaction and global self-esteem, but negatively related to the contingent type of self-esteem and intolerance of uncertainty. In contrast, it was expected that self-protection would be negatively correlated with basic need satisfaction and global self-esteem, but positively correlated with contingent self-esteem and intolerance of uncertainty. The majority of findings supported the research hypotheses. Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, bivariate and partial correlations among all variables of interest. Results show that, contrary to initially hypothesized, self-enhancement was positively related to contingent self-esteem and intolerance of uncertainty. Nevertheless, as expected, self-protection had negative correlations with need satisfaction and global self-esteem, whereas it had positive relationships with the contingent type of self-esteem and intolerance of uncertainty.

Because self-enhancement and self-protection were significantly correlated (r = .38, p < .01), partial correlation analyses were computed to investigate how each valuation motive would be associated with basic need satisfaction and the indicators of psychological adjustment when the other drive was held constant. The partial correlations (pr) were also reported at the bottom of Table 1. Besides bivariate correlations, the partial correlations between self-enhancement and variables of interest seemed to overlap better with the research hypotheses. Apparently, compared to their bivariate correlations, self-enhancement was associated with both basic need satisfaction (pr = .51, p < .01) and global self-esteem (pr = .38, p < .01) in larger magnitude when controlling for self-protection. Furthermore, the associations between self-enhancement and both contingent self-esteem and intolerance of uncertainty (negative indicators of psychological adjustment) were not significant when self-protection was held constant.

Likewise, the partial correlations between self-protection and both basic need satisfaction and global self-esteem showed considerable change. In particular, consistent with the expectations of research, self-protection was negatively associated with basic need satisfaction (pr = -.34, p < .01) and global self-esteem (pr = -.40, p < .01) in larger magnitude. To sum up, these findings supported the claim that the valuation motives differ from each other in terms of their associations with basic need satisfaction and psychological adjustment.

Associates of self-enhancement

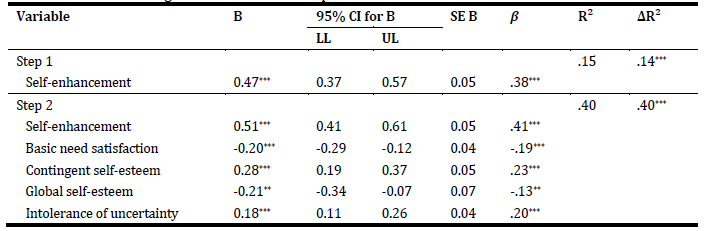

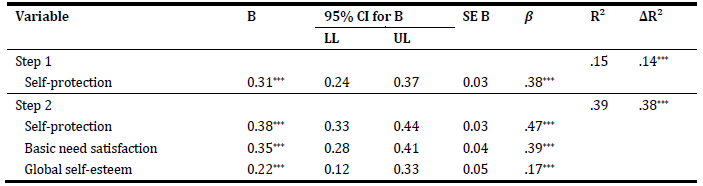

A hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to predict self-enhancement. Concerning the significant relationship between self-enhancement and self-protection (r = .38, p < .01), the analysis was computed controlling for the variance explained by self-protection. Self-protection was entered into the regression equation in the first step. Then, basic need satisfaction and global self-esteem were entered in the second step as predictor variables based on their significant partial correlations with self-enhancement.

As can be seen in Table 2, self-protection explained 14% of the total variance (β = .38, p < .001). After controlling for self-protection, as expected, it was found that self-enhancement was significantly associated with basic need satisfaction (β = .39, p < .001) and global self-esteem (β = .17, p < .001). This regression model accounted for 39% of the total variance. Apparently, the more people have need satisfaction and global self-esteem, the higher they use self-enhancing strategies identified as attempts to maintain positivity of self-views.

Table 2 Hierarchical regression results for self-enhancement

Note. CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit; *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

Associates of self-protection

A similar hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to predict self-protection. Concerning the significant relationship between self-enhancement and self-protection (r = .38, p < .01), the analysis was computed controlling for the variance explained by self-enhancement. It was entered into the regression equation in the first step. Then, basic need satisfaction, contingent-self-esteem, global self-esteem, and intolerance of uncertainty were entered in the second step as predictor variables with respect to their significant partial correlations with self-protection.

As can be seen in Table 3, self-enhancement explained 15% of the total variance (β = .38, p < .001). After controlling for self-enhancement, it was found that self-protection was negatively associated with basic need satisfaction (β = -.19, p < .001) and global self-esteem (β = -.13, p < .01), but positively associated with contingent self-esteem (β = .23, p < .001) and intolerance of uncertainty (β = .20, p < .001). This regression model accounted for 40% of the total variance. In summary, the more people have need satisfaction and global self-esteem, the less they use self-protective strategies that refer to attempts to defend self-views against negative self-relevant information. On the other hand, the more people have contingent self-esteem and intolerance of uncertainty, the higher they use these self-protective strategies.

Discussion

The current study aimed to differentiate self-enhancement from self-protection in terms of basic need satisfaction posited by SDT and the indicators of psychological adjustment (i.e., contingent self-esteem, global self-esteem, and intolerance of uncertainty). This is because, some researchers have argued that these motives are adaptive and have some benefits for human functioning (e.g., O’Mara et al., 2012; Sedikides & Luke, 2007; Taylor & Brown, 1988; Taylor et al., 2003), whereas some others portray them as maladaptive (e.g., Colvin et al., 1995; Robins & Beer, 2001). Considering these contradictory explanations, the current study is an attempt to understand the distinction between self-enhancement and self-protection in terms of optimal human functioning.

The self-evaluation process seems to become more important in terms of the generation-based approach. For example, Twenge (2014) describes today’s young people as ‘generation me’ and having particular characteristics, including higher self-esteem and proneness to self-enhance because of the cultural change highlighting individualism and self-confidence. Recent research has also demonstrated that young adults are likely to evaluate themselves above average and have positive self-views compared to previous generations (Twenge et al., 2012) with contradictory findings (Trzesniewski et al., 2008). The current study also aims to provide deeper insight adaptiveness of valuation motives in the younger generation, characterized as typically self-enhancers.

Results have revealed that each valuation motive has an association with the basic need satisfaction in a different direction. More specifically, the higher individuals experience basic need satisfaction, the more they use self-enhancing strategies. In contrast, lower need satisfaction is associated with using self-protective strategies. According to Deci and Ryan (2000), the fulfillment of the basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) has an essential role in psychological growth, integrity, and well-being. However, the thwarting of these needs can lead to self-protective processes (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). Although the current research focuses on the need dissatisfaction instead of the need thwarting, the findings support it as well.

When individuals’ basic psychological needs are not fulfilled, they can consequently have negative self-views. Thus, they are likely to feel that their self-esteem is threatened more and to attempt to reach self-regard through self-protective strategies. On the other hand, when individuals’ basic psychological needs are fulfilled, they can have positive life experiences that naturally improve their positive self-view. Hence, they are likely to maintain the positivity of self-concept through self-enhancing strategies. Previous research has provided empirical support for the associations between defensive processes and both autonomy orientation and autonomy motivation that are related to need satisfaction (e.g., Hodgins et al., 2006; Knee & Zuckerman, 1996; Lynch & O’Mara, 2015). However, the current research provided a deeper insight into both self-enhancement and self-protection in connection with the satisfaction of basic psychological needs, which is an essential determinant of optimal human functioning.

This research also provides evidence on the adaptiveness of the valuation motives concerning particular individual differences, such as global self-esteem (a positive indicator of psychological adjustment), contingent self-esteem, and intolerance of uncertainty (negative indicators of psychological adjustment). Although previous research has already given explanations about the relationships between valuation motives and self-esteem, they have focused on either the stability of self-esteem or particular strategies of valuation motives (e.g., Baumeister et al., 1989; Hepper et al., 2010; Kernis et al., 2008). In the current study, it is demonstrated that the associations of valuation motives with both global and contingent self-esteem should be considered separately, since self-enhancement and self-protection seem to be distinguished from each other in terms of their association with different aspects of self-esteem.

For example, whereas self-enhancement is positively associated with the stability of self-esteem (i.e., global self-esteem), self-protection is negatively associated with it. Furthermore, consistent with previous research (e.g., Kernis et al., 2008), self-protection is positively associated with the instability and fragile aspect of self-esteem (i.e., contingent self-esteem). On the other hand, self-enhancement seems to be uncorrelated with contingent self-esteem, which refers to the unstable and fragile aspect of self-esteem. Indeed, Deci and Ryan (1995) see contingent self-esteem as associated with defensive processes to avoid the decrease in self-worth under potential self-threatening circumstances. These findings empirically supported their argument. Individuals higher in contingent self-esteem seem to use self-protective strategies over self-enhancing strategies to avoid negative self-views.

From the point of optimal human functioning, the current study also provides valuable findings on the relationship between valuation motives and intolerance of uncertainty, which was approached as an indicator of psychological adjustment for the reason that intolerance of uncertainty is linked to mental health indicators such as worry, anxiety, and depression (e.g., Boelen & Reijntjes, 2009; Buhr & Dugas, 2006). In this study, the associations between valuation motives and intolerance of uncertainty provide some evidence to uncover the distinction between self-enhancement and self-protection. Accordingly, as expected, self-protection is positively associated with intolerance of uncertainty. However, self-enhancement appears not to be associated with this tendency. More specifically, individuals who are more intolerant of uncertainty seem to use self-protective strategies rather than self-enhancing strategies. Individuals tend to use self-protective strategies to prevent a decrease in self-regard when they perceive a threat to self-esteem (Alicke & Sedikides, 2009; Sedikides, 2007). Correspondingly, individuals who have higher intolerance of uncertainty might interpret uncertain situations and events more threatening to self-esteem. Thus, they might need to use self-protective strategies to defend their self-regard in case of a potential decrease in self-worth.

To sum up, in line with the conflicting views on the adaptive nature of valuation motives, some researchers propose that self-enhancement is adaptive (e.g., Kurman & Eshel, 1998; O’Mara et al., 2012; Sedikides & Luke, 2007; Taylor et al., 2003), whereas others suggested that it seems maladaptive (e.g., Colvin et al., 1995; Robins & Beer, 2001). The current research can contribute to our understanding of the motivational aspects of the self as a social psychological phenomenon with the view that self-enhancement and self-protection are distinct motives, and thus the adaptive nature of these motives can be considered separately. Additionally, clarifying the distinction between these motives based on their adaptive nature can also help to pursue potential explanations regarding their associations with different psychological phenomena, such as close relationships (e.g., Schütz & Tice, 1997; Wood & Forest, 2011), prejudice and discrimination (e.g., Fein & Spencer, 1997), work motivation (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2018), academic performance (e.g., Gramzow et al., 2014), or mental health (e.g., Alloy et al., 2011; Lei & Duan, 2016).

The current findings may also serve to make some implications in terms of the characteristics of the younger generation. Twenge (2014) argues that younger adults are more self-confident, egocentric, and more narcissistic by reason of cultural change that supports individualism and self-esteem. In this respect, the adaptive nature of valuation motives can also be taken into account, especially in terms of parental practices or interventions in the field of education that support the self-esteem of young adults.

In conclusion, the current study basically bolsters the view that self-enhancement and self-protection are distinct motives. Moreover, in order to get a deeper insight into these valuation motives and their adaptive nature, basic psychological needs can be a reasonable framework. The current findings also suggest that these motives are linked to positive and negative aspects of psychological adjustment diversely. It can be implied that self-enhancement has an association with increasing psychological adjustment, whereas self-protection is negatively linked to it. The current research also supports the claims that basic psychological needs and valuation motives are universal (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Sedikides et al., 2003).

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The current study has some limitations. First of all, participants were undergraduates with the majority being female. Future research should examine the distinction between valuation motives and their adaptive nature in the samples which have different characteristics (e.g., broader age range, gender-balanced, representative for socioeconomic status) to contribute to the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the current study points out the differences in valuation motives in younger adults, who are defined as ‘generation me’ and having higher self-esteem and more positive self-views (Twenge, 2014). Nonetheless, the study does not include generation-based comparisons. Future research conducted with cross-sectional design should also include age-based group comparisons, while examining young adults’ characteristics related to the self-evaluation process.

Another limitation is related to the cross-sectional method of the study that is limited to inferring causal relationships. As Robins and Beer (2001) suggest that self-enhancement is adaptive in the short-term, but maladaptive in the long-term; future research can use longitudinal methods to replicate the obtained associations between self-enhancement/self-protection and psychological adjustment in the current study. Although consistent results with the research hypotheses were obtained in this study, the explained variance for each valuation motive and some Beta values for the associations among variables (e.g., the associations of self-enhancement and self-protection with global-self-esteem) indicate that the potential links of these motives with different characteristics (e.g., personality traits) can be examined while explaining these motives.

Besides that, to assess their associations with self-enhancement/self-protection, only stable and fragile aspects of self-esteem were measured. Future research that examines the other aspects of self-esteem (e.g., implicit self-esteem) in relation to valuation motives could contribute to understanding the associations between self-enhancement/self-protection and self-esteem better. Furthermore, examining the links between self-protection and different types of psychopathologies (e.g., depression, anxiety and personality disorders) can contribute to understanding the self-evaluation process of the individuals suffering from psychopathology.