For a long time, research on parenting mainly studied caregiving and parenting behavior of mothers and thus examined mothering instead of parenting. However, over recent decades fathering research across various disciplines has increased (Cabrera et al., 2000; Rodrigues et al., 2021; Schoppe-Sullivan & Fagan, 2020; Verhoeven et al., 2012). As a consequence, current research on parenting increasingly differentiates between mothering and fathering. Although, empirical evidence has shown that mothering, as well as fathering play an important role for child development and adjustment (Baptista et al., 2018; Fernandes et al., 2021; Okorn et al., 2021; Rodrigues et al., 2021), there is still a scientific debate on concepts and assessment strategies (Fagan et al., 2014; Paquette, 2004; Volling et al., 2019). This shows a current research lacuna in this field, especially as regards whether mothers and fathers differ in their parenting styles or whether individual expectations of how mothers and fathers should react as parents differ (Murphy et al., 2017). This is also a current topic in attachment research.

Attachment research on mothering and fathering

Children develop attachments to mothers and fathers (Bowlby, 1982; Grossmann & Grossmann, 2020), although most attachment research is on attachment to mothers. From an attachment perspective, children need attachment figures as a safe haven in times of challenging negative emotions and distress, as well as a secure base to explore the world when feeling secure and experiencing positive affect (Ainsworth, 1989; Bowlby, 1982; Grossmann et al., 2008). Parents can offer safe haven and secure base behavior by showing both sensitivity and sensitive exploration support (Grossmann et al., 2008; Kerns et al., 2015; Monteiro et al., 2008). However, sensitivity has been mainly studied in the context of mothering as the most influential caregiving characteristic in attachment research, with some exceptions (Whipple et al., 2011). Sensitivity is defined as the caregiver`s ability to perceive the child`s signals, to interpret them correctly and to respond to them promptly and appropriately (Ainsworth et al., 1974). Studies have shown that maternal sensitivity as offering safe haven to the child in times of distress is a major predictor of children’s attachment security to their mother (Grossmann & Grossmann, 2020; Leerkes & Zhou, 2018; Verhage et al., 2016). Moreover, maternal sensitivity longitudinally predicts developmental outcomes in many adjustment domains in later life (Grossmann & Grossmann, 2020; Raby et al., 2015).

However, studies on paternal sensitivity as predictor of attachment security and other developmental outcomes do not reveal identical effects on later development (Grossmann et al., 2008; Rodrigues et al., 2021). Mean effect size of the association between maternal sensitivity and the child`s attachment security to the mother is moderately strong (r = .24), while associations of paternal sensitivity as providing safe haven with attachment security to the father are less strong (r = .12) (Lucassen et al., 2011; Zimmermann, 2017). Thus, other aspects of the child-father relationship might be important for adaptive child development.

Earlier research focused on paternal involvement, mainly quantitatively assessed as shared time between father and child. In many families, the amount of shared time with the child is unequal for mothers and fathers (e.g., McMunn et al., 2017). However, the quantity of paternal involvement is not always positively associated with children’s attachment security or sensitive or appropriate fathering (Brown et al., 2007, 2012; Lickenbrock & Braungart-Rieker, 2015). Thus, the quality of involvement might be more relevant for child development, especially for the development of attachment security. Current research considers such qualitative instead of quantitative aspects of parenting and involvement and distinguishes between these relevant aspects of mothering and fathering. Considering the child’s perspective, Kerns et al. (2015) showed that children reported more safe haven support from mothers and more secure base support from fathers. Thus, secure base behavior might play a major role in the child-father relationship (Grossmann & Grossmann, 2020; Grossmann et al., 2008).

Attachment research has shown that paternal autonomy support is a major predictor of the child’s attachment security to the father, academic achievement, and adaptive psychosocial functioning (Grossmann et al., 2002; Vasquez et al., 2016). Autonomy support includes encouragement for exploration, guidance for goal-oriented play, as well as praise and guidance for the child's emotion (Grossmann & Grossmann, 2020) and can be understood as providing a secure base for exploration. Moreover, paternal rough and tumble play also predicts child attachment security (Newland et al., 2008). Paternal challenging behavior encourages the child to exhibit “risky behavior” during play or to go out of his or her own emotional “comfort zone”, while the parent ensures safety and security (e.g., “inciting children to take the initiative in unfamiliar situations, explore, take chances, overcome obstacles, be braver in the presence of strangers, and stand up for themselves”; Paquette & Dumont, 2013, p. 1). Similarly, the father-child activation relationship fosters regulation of “risk-taking” during the child’s exploration of his or her environment. These have both been shown to be relevant fathering characteristics for children’s mental health (Gaumon & Paquette, 2013; Majdandžić et al., 2014. In this early parenting context and in contrast to the adolescent literature, the term “risky behavior” does not include behaviors that lead to physical injuries or mental problems for the child.

Based on Grusec`s model of child socialization, mothering (i.e., sensitivity) may occur mainly in the domains of protection and reciprocity, whereas fathering (i.e., sensitive challenging behavior) may also occur more often in the domain of guided learning and self-control (Grusec et al., 2017; Grusec & Davidov, 2010).

Beliefs about ideal mothers and fathers

Studies on beliefs about ideal parenting have shown that most parents describe a good parent as a responsible person who is sincerely engaged with the child and strives for his or her best (Widding, 2015). However, ideal engagement and caring for a child may differ between countries and cultures, and in the relative salience of sensitivity or autonomy support within the culture and between parents (Bornstein & Cote, 2004; Davidov, 2021; Grossmann et al., 2008).

In a unique study, Mesman et al. (2016) showed that mothers from different countries describe an ideal mother as sensitive, using the Maternal Behavior Q-Set (MBQS; Pederson & Moran, 1995). However, they neither included fathers in their sample nor examined ideal fathering. Fathering may be different from mothering (Paquette, 2004) and with historical changes in the role of fathers in many countries, the increasing involvement of fathers in child rearing may lead to changes in expectations of the ideal father (Pruett et al., 2017). Morman and Floyd (2006) showed that fathers and sons reported love, availability, and role modeling as most important characteristics of ideal fathers in an open-ended question format. Fathers and sons also often characterized ideal fathers as providers and teachers. However, this study did not include female participants or assess ideal mothering. Thus, a study examining characteristics of ideal mothers and ideal fathers in both male and female participants is missing.

Moreover, ideas about ideal mothering may well differ between cultures (O’Brien et al., 2020) and may be affected by own parenting experiences and their positive or negative evaluation (Bar-On & Scharf, 2016), as well as specific attachment related experiences (Cassidy, 2000). Ideals can also differ when characterizing parenting by mother and father (Putnick et al., 2012). In sum, beliefs about ideal parenting may depend on whether ideal mothers or ideal fathers are characterized, but also may depend on the rater’s gender, cultural, and educational background or own parenting experiences. However, it is also important to consider which parenting dimensions are studied in mothers and fathers. Grusec and Davidov (2010) emphasized that different parental caregiving domains have different effects on child development, but mainly reviewed research on mothering. Research on attachment to mother and father (Grossmann et al., 2002; Zimmermann, 2017) and research on differences in caregiving by mothers and fathers (Majdandžić et al., 2016; Paquette, 2004) lead us to suggest that parenting ideals should be examined regarding three dimensions: (1) sensitivity, (2) challenging parenting behavior, which often is operationalized as insensitive challenging caregiving, but also (3) sensitive challenging parenting behavior, adapting one’s challenging parenting to the child’s abilities and emotional needs (Grossmann et al., 2002).

Influences on beliefs about ideal mothers and fathers: An attachment perspective

Based on early attachment experiences, such as sensitivity, effective regulation, emotional and autonomy support or rejection, devaluation, and emotional insecurity in emotionally overwhelming situations, children develop internal working models of attachment. Following Bowlby (1973), the content of internal working models of attachment figures includes perceptual details of who they are, procedural information concerning how they could be accessed, and beliefs about how they probably will react. Internal working models control the perception, interpretation, and appraisal of social situations (Zimmermann, 1999). Securely attached individuals experience their parents as emotional available, sensitive, supportive, and effective in their external regulation. They develop internal working models according to these experiences and expect their attachment figures to be a reliable source of support and effective regulation. Whereas insecurely attached individuals experience negative reactions to their attachment needs and develop internal working models of their parents as being unsupportive, emotional unavailable, rejecting, and not effective in their external emotional regulation. Thus, individuals might develop an ideal of parenting based on their own attachment experiences, which may differ for securely and insecurely attached individuals (Cassidy, 2000; George, 1996; Grossmann et al., 2008). However, as Bretherton (1990) has pointed out, internal working models might be specific for each caregiver and can differ for mother and father, as the attachment patterns to each parent can be independent (Bowlby, 1980). Thus, central aspects of internal working models of mother and father need to be examined in their effect on participants’ parenting expectations. This includes whether the parent perceived the child’s emotional distress, whether the mother or the father is able to effectively regulate and sooth the child in times of emotional distress and whether proximity seeking or communication in times of distress is perceived as an appropriate strategy in relation to mother and father.

Aims of the present study

Studies on ideal parents including both parents and including male and female participants are rare or even missing. In the current study, we examined such parenting ideals from an attachment perspective.

Specifically, we had four aims in our study:

First, we wanted to examine similarities and differences in the representations of ideal mothers and fathers as sensitive challenging in their parenting behavior in the Parenting Q-sort (PQ). We expected that, nowadays, parenting ideals of mothers and fathers would be similar.

Second, we were interested in the qualitative analyses of the most typical and most untypical characteristics of current ideals of mothers and fathers.

Third, as an extension of the first research question, we examined differences between ideal mothers and fathers with regard to the PQ mega-items: sensitivity and challenging behavior, as well as domain-specific differences in these attachment domains. We expected that beliefs about ideal mothers would be characterized by more sensitivity and less challenging behavior compared to beliefs about ideal fathers. In contrast, we expected that ideal fathers would be more characterized by challenging compared to sensitive behavior.

Fourth, we were interested in whether participants’ own attachment security, based on their working models of parents as emotionally available attachment figures, would influence parenting ideals on mothering and fathering. We expected participant’s own attachment security to be associated with an ideal of parents as sensitive challenging and sensitive.

Method

Participants

Participants were 175 German, mainly Caucasian, low-risk adults. Age ranged from 20 to 45 years, with a mean age of 30.94 years (SD = 5.88 years). The sample consisted of an approximately equal number of males and females (52% female). One hundred and fifty-five participants reported German as their native language (88.6%), four participants reported German and a second language as their native languages: two participants gave Russian, one Italian and one Moroccan as a second native language. 16 participants reported another native language rather than German: Russian (four participants), Bulgarian (three participants), Polish, Czech, Arab, Turkish, Farsi, French, Portuguese, and Swedish (one participant each). Level of education was rather high with a mean of 12.48 school years. The highest level of education was a University Degree (Diploma, Master, PhD), the lowest a General Certificate of Secondary Education. Ten participants did not have the general qualification for university entrance in Germany. 84.6% reported they lived in a steady partnership. The sample was divided in 39.4% with no child, 39.4% with one child, 17.7% with two children, and 3.4% with three children. Children’s age ranged from one month to 120 months, but each parent in the sample had at least one child younger than 60 months.

Measures

Beliefs about ideal parenting. Beliefs or representations of the ideal parent regarding sensitivity, challenging, and sensitive challenging behavior as dimensions of parenting were assessed using the newly developed Parenting Q-sort (PQ; Iwanski et al., 2019). Inspired by the Maternal Behavior Q-sort (MBQS; Pederson & Moran, 1995), the PQ combines indicators of sensitive parenting with other parental behaviors based on an expanded literature review of research on mothering and fathering. While the MBQS focuses on maternal sensitivity as one central aspect of parental behavior, the PQ includes a broader array of parenting facets, like sensitivity, rough and tumble play, challenging behavior, activation-relationship, support of exploration, scaffolding, cooperation, intrusiveness, warmth, and sensitive challenging behavior. The PQ consists of 99 items about facets of parenting that participants have to sort into nine categories from “most uncharacteristic” to “most characteristic” when describing the ideal mother or ideal father. Consistent with the standard Q-sort procedure according to Block (1978), subjects first had to sort the items printed on cards into three categories: characteristic, neither characteristic nor uncharacteristic, and uncharacteristic for each ideal parent. In a second step, participants were asked to sort all items of the characteristic category into the three categories: most characteristic (stack 9), very characteristic (stack 8), and characteristic (stack 7), separately for the ideal mother and father. Similarly, items of the uncharacteristic category were sorted into the categories most uncharacteristic (1), very uncharacteristic (2), and uncharacteristic (3). Finally, the remaining items were sorted into the categories rather characteristic (6), rather uncharacteristic (4), and neither characteristic nor uncharacteristic (5). This lead to a fixed approximately normal distribution of Q-sort items with 8, 9, 11, 14, 15, 14, 11, 9, 8 items for the respective category according to the standard Q-sort procedure. Thus, each participant provided a Q-sort for an ideal mother and ideal father, sorting all 99 items on a 9-point scale.

In line with the study by Mesman et al. (2016), participants were asked to describe the ideal parent, not their own parenting or own parenting experiences as a child. The instruction explicitly emphasized that there were no correct or incorrect solutions. All investigators of this study were trained by the authors of this paper in the standardized procedure of Q-sorting. All questions the subjects had concerning the meaning of an item or the sorting procedure were answered regarding the standardized protocol. Each individual Q-sort (for the ideal father and ideal mother, respectively) for each participant represents one individual variable set, with 99 items (according to the 99 PQ items). Scores range from 1 (stack most uncharacteristic) to 9 (stack most characteristic). Similar to the prototype of a sensitive mother developed for the MBQS (Pederson & Moran, 1995), we developed a prototype for sensitive challenging behavior for the PQ integrating aspects of pure sensitivity, pure challenging behavior, and their combination in the sense of sensitive challenging parenting behavior described by Grossmann et al. (2002). The participants’ representations of the ideal mother and the ideal father on the dimension of sensitive challenging parenting were computed by correlating the individual Q-sorts with this criterion Q-sort for “sensitive challenging parenting behavior” with a potential range from -1.00 to +1.00. This prototypic criterion Q-sort for the ideal sensitive challenging parent was developed by the first and last author of this paper. Agreement of both individual Q-sorts on the ideal parent was high with r = .88, p < .0001. Thus, a mean score of both independent Q-sorts was used as the prototypic criterion Q-sort for sensitive challenging parenting behavior. Higher scores represent a more prototypical sensitive and challenging parenting behavior, according to attachment theory and research on parenting. In addition, two mega-items were computed for the parenting dimensions “sensitivity” and “challenging behavior”. The mega-items represent specific scales within the PQ and have a range from 1 to 9 with higher scores indicating the representation of higher sensitivity and highly challenging behavior. The mega-item sensitivity consists of 26 items (α = .67) assessing aspects of Ainsworth’s sensitivity scale (e.g., “interprets child’s signals appropriately as can be seen from the child’s reaction”). The mega-item challenging parenting behavior consists of ten items (α = .56) assessing parenting aspects of activation, competition, and rough and tumble play (e.g., “cavorts with child without considering the child’s reaction”). The single Q-sort items of the two mega-items are drawn from already validated Q-sorts or parenting questionnaires (e.g., Majdandžić et al., 2016; Pederson & Moran, 1995).

All participants described the ideal mother as well as the ideal father with the PQ: 50% started with the description of the ideal mother, 50% with the ideal father. Between both Q-sorts, participants answered different questionnaires.

Attachment. Participants’ attachment was assessed by use of the Attachment-Behavior-Representation Questionnaire (ABR-Q; Zimmermann, 2004), a self-report questionnaire assessing attachment security to mother and father. The ABR-Q measures two main attachment dimensions: attachment behavior strategy towards parent (e.g., “I tell my father/mother when I am sad”; mother α = .87, father α = .90) and attachment representation of parental emotional availability. Attachment representation consists of two subscales: parental perception of adolescents’ distress (e.g., “My mother notices when I am feeling anxious”; mother α = .83, father α = .90) and parents’ effective support (e.g., “My father helps me when I am sad”; mother α = .88 father α = .93). The ABR-Q consists of 15 items on attachment processes when experiencing negative emotions, per attachment figure. Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 “never” to 5 ”always”. Higher scores indicate a higher attachment security. Validity has been examined in earlier studies (see Iwanski et al., 2021).

We assigned subjects to three attachment groups, based on the procedure described in Iwanski et al. (2021). It resulted in a secure group: N = 73 attachment to mother and N = 55 attachment to father, an insecure-avoidant group: N = 76 attachment to mother and N = 94 attachment to father, and an insecure-ambivalent group: N = 24 attachment to mother and N = 20 attachment to father. Six subjects did not report information on attachment to father, while two subjects did not report information on mother attachment.

Results

Effects of gender and own parenthood status on parenting ideals

First, we examined possible effects of gender and own parenthood status on participants’ representations of ideal mothers and fathers as sensitive challenging, as well as on the two mega-items sensitivity and challenging behavior. A gender x parenthood ANOVA revealed no significant overall main effects of gender or own parenthood status, and no significant interaction effect on the representation of ideal mothers or fathers. Thus, both female and male participants, as well as parents and nonparous participants describe the ideal mother and father in a comparable way as sensitive, challenging, and sensitive challenging.

Similarities and differences of mother and father ideal as sensitive challenging

Next, we examined whether the representations of ideal mothers and ideal fathers as sensitive challenging were associated and whether the representation of the ideal mother differs from the ideal father in sensitive challenging parenting behavior. Zero-order correlations revealed a significant positive association between ideal mother and ideal father as sensitive challenging, r = .60, p < .001. However, a paired t-test also showed that the representation of the ideal mother (M = .757, SE = .01) was more convergent with the prototypic criterion sort of the ideal sensitive and challenging parent than it was the case for the representation of the ideal father (M = .744, SE = .01), t(174) = 2.23, p = .03, Difference = .13; CI 95% [.002, .024]; Cohen’s d = .17.

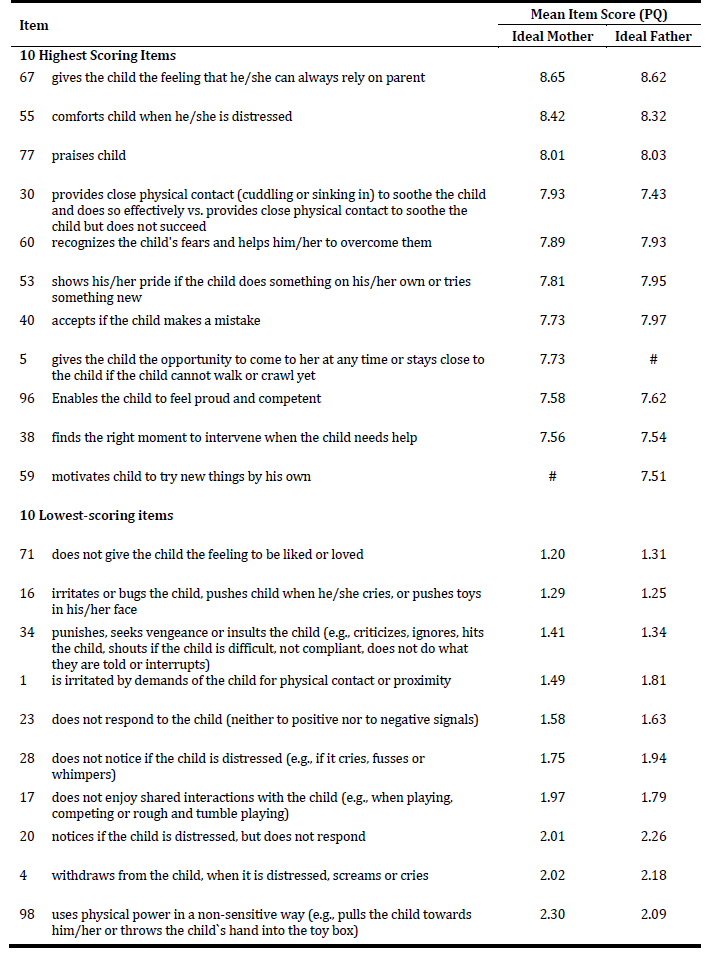

Next, we were interested in a more descriptive and qualitative analysis of the participants’ representations of the ideal mother and father. Thus, besides using a theoretically derived prototype of sensitive challenging parenting, we also wanted to identify the participants’ hierarchy of parenting items in the PQ when characterizing an ideal mother and ideal father. We computed the mean rank of each PQ item for ideal mother and ideal father Q-sorts respectively over all participants and sorted them in descending order. Table 1 shows the most characteristic and most uncharacteristic items of the ideal mother and ideal father within this sample. Most of the top and bottom items are similar for both ideal mother and father. The majority of the ten most characteristic items reflect different aspects of sensitivity according to Ainsworth et al. (1978), such as emotional interaction and availability for the child, perceiving the child`s signals, and responding to them in an appropriate and regulating way. However, one out of the ten most characteristic items differed. Whereas the ideal mother is most characteristically described as “gives the child the opportunity to come to parent any time or stays close to the child” (Item 5), the ideal father is most characteristically described as “motivates his child to try new things on her/his own“ (Item 59). This item belongs to the field of sensitive challenging parenting behavior. There is, however, complete agreement regarding the most uncharacteristic items for ideal mother and ideal father. These items reflect a lack of sensitive and responsive parenting behavior, negative or flat affect, and harsh parenting.

Table 1 The 10 highest scoring and 10 lowest scoring maternal and paternal behavior PQ items across all participants for the ideal mother and ideal father (N = 175).

Note: Mean item scores can range from 1 to 9. # Item not in the TOP 10 for this ideal parent.

Similarities and differences in the parenting domains’ sensitivity and challenging behavior

As a next step, we analyzed similarities and differences between ideal mother and ideal father representations in the mega-items for the two parenting domains sensitivity and challenging behavior of the PQ. These mega-items represent specific scales within a Q-sort (Cole-Detke & Kobak, 1996; Spangler & Zimmermann, 1999), with higher scores indicating the representation of higher sensitivity or highly challenging parenting behavior.

Correlational analyses revealed significant positive associations between ideal mother and father for sensitivity, r = .46, p < .001, and for challenging behavior, r = .24, p = .002, showing that participants who described an ideal mother as more sensitive or challenging also tended to describe an ideal father as more sensitive or more challenging, respectively. Interestingly, associations between these two parenting dimensions - sensitivity and challenging parenting behavior - within the ideal mother descriptions were not significant, r = .08, p = .30. Thus, when describing ideal mothers, those parenting dimensions were independent. In contrast, both parenting dimensions within the ideal father descriptions were significantly negatively correlated, r = -.19, p = .012, suggesting that participants characterized ideal fathers as either more sensitive or more challenging. The correlation between both parenting dimensions for the ideal father differed significantly from the correlation for ideal mothers, z = 2.51, p = .006.

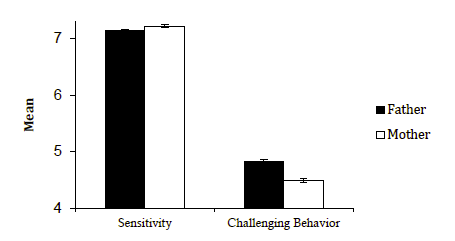

Within-parent differences in sensitivity and challenging behavior. First, we looked at within-parent differences comparing sensitivity relative to challenging parenting behavior and potentially indicating a hierarchy of the two parenting domains within each parent ideal. Paired t-tests showed that the ideal mother was described as primarily more sensitive compared to challenging, t(174) = 67.10, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 5.07. Similarly, the ideal father was primarily described as more sensitive than challenging t(174) = 43.61, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 3.30. Figure 1 shows means and standard errors for sensitivity and challenging parenting behavior for the representation of the ideal mother and father.

Figure 1 Mega-Items of the PQ for sensitivity and challenging parenting behavior of an ideal mother and an ideal father (Mean and SE). Note. Theoretical range 1 to 9.

Between-parent differences in sensitivity and challenging behavior. Next, we were interested in domain-specific differences in the two parenting domains between ideal mother and father. Paired t-tests between both ideals showed significant differences between the representation of an ideal mother and father with regard to sensitivity, t(174) = 3.19, p = .002, Cohen’s d = .24, and challenging behavior, t(174)= -6.82, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .52. Thus, participants described ideal mothers as more sensitive and also as less challenging compared to ideal fathers (see Figure 1).

Effects of attachment on parenting ideals

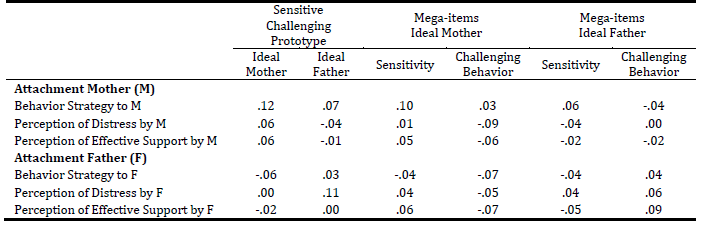

Finally, we examined whether participants’ attachment security and attachment patterns are associated with their beliefs about ideal parenting. Table 2 shows that the dimensional scores of attachment security to mother and father were not significantly associated with beliefs about ideal parenting.

However, participants’ attachment patterns to the mother showed effects on the beliefs about the ideal mother as sensitive challenging, F(2,170) = 4.30; p = .015, Cohen’s d = .51, and also on the mega-item sensitivity of the ideal mother, F(2,170) = 3.23; p = .042, Cohen’s d = .41. Participants classified as avoidantly attached to the mother had significantly lower scores in their sensitive challenging mother ideal (M = .74, SE = .01) compared to participants with secure (M = .77, SE = .01) and insecure-ambivalent attachment classifications (M = .77, SE = .01). Similarly, participants classified as avoidantly attached to their mother had significantly lower scores in sensitivity of the ideal mother (M = 7.16, SE = .04) compared to participants with secure attachment classification (M = 7.28, SE = .03). There were no significant effects of attachment classification to own father on beliefs about ideal mothers or ideal fathers.

Discussion

The main goals of this study were to examine similarities and differences in representations of ideal mothers and ideal fathers, and potential influences of attachment on parenting ideals.

Sensitive challenging in ideal mothers and ideal fathers

The first main finding of this study is that the participants’ representation of an ideal mother is more convergent with the prototypic criterion sort of the ideal sensitively challenging parent compared to their representation of an ideal father. Thus, expectations of ideal mothers to be sensitively challenging is higher than the expectations of ideal fathers. However, these beliefs about the ideal mother and father were also significantly associated, suggesting that participants have similar expectations towards ideal mothers and fathers at least regarding sensitive challenging parenting behavior. Characterizing an ideal mother as highly sensitive challenging expands the results reported by Mesman et al. (2016) that the ideal mother is a sensitive mother. We conclude that an ideal mother not only is highly sensitive but also is highly sensitive challenging towards her child, supporting the child’s autonomy adjusted to his/her abilities, current needs, and interests. The sample mean score for the sensitive challenging parenting prototypicity (i.e., mean correlation with the prototypic sensitive challenging criterion sort) for mother and father is rather high (r = .76 and r = .74 respectively, theoretical range -1.00 to +1.00) which is quite comparable to the ideal prototypicity score for maternal sensitivity (r = .64) reported by Mesman et al. (2016). A closer look at the country differences in ideal maternal sensitivity reported by Mesman et al. (2016) revealed that the maternal and paternal sensitive challenging mean scores in our study are similar to the mean ideal sensitivity score from the Dutch sample in the study by Mesman et al. (2016). The Netherlands is rather comparable to Germany regarding parenting standards and living conditions. We therefore conclude that at least for European countries ideal mothers not only provide safe haven but also provide sensitive autonomy support and, therefore, secure base.

Interestingly, participants also described ideal fathers as highly sensitive challenging. The mean prototypicity score for ideal fathers was moderately but significantly lower compared to the mean ideal mother sensitive challenging score. As the effect size of the difference is rather low, we conclude that both ideal mothers and fathers are comparably expected to be highly sensitive challenging towards their children. This implies that an ideal parent, mother or father, is not only characterized by one caregiving dimension, either providing safe haven or secure base but by combining both. This is in line with current theorizing on attachment to mother and father (Grossmann & Grossmann, 2020). However, as the participants come from Germany, a Western European country, the results should not be generalized without replication in other countries and cultures.

The second main finding of this study was that in the qualitative description of the ideal mother and ideal father nine out of ten of the most characteristic PQ items and all of the ten most uncharacteristic PQ items were identical for ideal mothers and ideal fathers. The majority of the most characteristic PQ items considered aspects of sensitivity, whereas the most uncharacteristic items described a lack of sensitive and responsive parenting, expressing negative affect or even harsh parenting. Interestingly, the most desirable parenting characteristics for both mothers and fathers describe facets of sensitivity. Thus, not only ideal mothers but also ideal fathers are expected to be sensitive.

These single item results are corroborated by our comparison of the sensitivity and challenging PQ mega-items. Both mother and father ideals were described as far more sensitive than challenging, suggesting a similar hierarchy of caregiving dimensions for ideal mothers and ideal fathers. We therefore conclude that both ideal mothers and fathers are characterized as sensitive parents. Thus, the attachment perspective on ideal parents as being sensitive is expected from mothers and fathers. This may contradict theorizing and empirical results repeatedly emphasizing that fathers are more challenging than mothers and that this difference may have positive consequences for the child’s development (Majdandžić et al., 2016; Paquette, 2004). In fact, the results of our study show that ideal fathers are expected to be more challenging than ideal mothers. However, when comparing sensitivity and challenging parenting behavior within the description of the ideal father, participants’ expectations regarding ideal fathers’ challenging behavior is not at the expense of ideal fathers’ sensitivity. Ideal fathers are similar in sensitivity but more challenging than ideal mothers.

Within the scientific debate whether mothers and fathers are or should be different or similar in their parenting behavior (Fagan et al., 2014; Paquette, 2004), we conclude that using the same parenting assessment tool for mothers and fathers can help to gain a differentiated view on mothering and fathering. We find similarities, but also relative differences.

Our findings highlight the importance of considering existing representations of ideal mothers and ideal fathers including their differences and their similarities. As a practical implication, family counseling, family therapy, or family-based intervention and prevention programs should address existing individual differences in representations of being an ideal mother or ideal father between their clients. Although our results showed that both ideal mothers and ideal fathers are expected to be sensitive and sensitive challenging at the same time, ideal fathers also are expected to be a bit more challenging than ideal mothers. Parenting programs should include this relative difference for mothers and fathers in challenging parenting behavior when emphasizing the relevance of sensitivity and sensitive challenging. Practitioners should consider that avoidantly attached adults have lower expectations regarding the sensitivity of an ideal mother potentially leading to differences in actual caregiving behavior. Moreover, the individual parenting of a mother or a father might differ from these described ideals and, consequently, might be a source of parenting stress when own actual parenting differs from the own ideal of a perfect parent, or when such discrepancy is perceived in one’s partner’s caregiving behavior. Thus, working with parenting ideals in interventions might be a promising extension in reducing parenting stress in families.

Attachment and parenting ideals

Parenting ideals may reflect current cultural or societal expectations of family life, shared responsibilities, or gender role stereotypes. However, own individual caregiving experiences or own experiences of being a parent may also influence such parenting ideals. Own attachment experiences with mothers and fathers or their reflection may influence what individuals expect or perceive as ideal mothering or fathering. Parents’ caregiving systems are influenced by their own internal working models of attachment (Bowlby, 1982; George, 1996). However, it may not be the direct report on attachment relationships but the organization of attachment memories and their evaluation that influences caregiving. The development of the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) is based on the fact that infants` attachment classification was not predicted by their parents` report of their own caregiving memories but by the coherence and concordance of those memories and their evaluation as coded in the AAI (Main et al., 1985). The results of our study show a similar pattern. We did not find significant associations between participants` self-reported dimensional attachment security scores to their mother or father and their ratings of ideal parenting. However, when using a classification procedure to identify groups with secure, insecure-avoidant, and insecure-ambivalent attachment patterns based on concordance of attachment behavior and attachment representation (Iwanski et al., 2021) attachment group effects appeared. Participants with an avoidant attachment pattern to their mother described an ideal mother as less sensitive compared to the secure attachment group and as less sensitive challenging compared to both the secure and insecure-ambivalent attachment group. Thus, similar (but of course not identical) to AAI patterns, the insecure-avoidant attachment group showed a reduced valuing of attachment related parenting, as described in sensitive challenging parenting, whereas the secure and the insecure-ambivalent group did. Therefore, we see that some of the variability found in ideals of parenting is influenced by attachment patterns to the mother. This is in line with other research showing that some but not all aspects of AAI patterns or attachment style are associated with parenting expectations or working models of own parenting (Scharf & Mayseless, 2011). As avoidant attachment is associated with experiences of more constant rejecting parenting compared to ambivalent attachment, the difference in ideal parenting may well fit their different working models of attachment figures. The specific association of parenting and avoidance has also been found in other research, where higher avoidance predicted less sensitivity for both men and women (Millings & Walsh, 2009). In contrast, ideal sensitive challenging parenting behavior described by the insecure-ambivalent group differs from the insecure-avoidant group, but not from the secure attachment group. This may be one of the reasons why the dimensional attachment scores did not show significant associations with the parenting ideal scores, as the two insecure attachment groups are not well differentiated in one-dimensional attachment scores but differ in their parenting ideals.

We found no effects of participants’ gender or own parenthood status on the representations of ideal mothers and fathers for any of the three parenting dimensions. Thus, we can conclude that ideals on fathering or mothering, as assessed here, do not depend on own gender. Both men and women in this study have comparable ideals for parenting. However, our sample is highly educated and, in many studies, parental education is positively associated with observed sensitivity. Thus, the results may differ in other samples with a broader educational background and replication seems necessary. However, the results expand earlier studies (Mesman et al., 2016; Morman & Floyd, 2006) by including both male and female participants to describe ideal mothers and fathers regarding their parenting. Interestingly, being a parent on his or her own had no influence on whether an ideal mother or ideal father was expected to be sensitively challenging, sensitive, or challenging. Thus, we do not find any effect that nonparous participants have more idealistic or too perfect expectations of how ideal parents should behave, or that experienced parents as “experts” have lower standards for parenting or show clearer differences in gender role stereotypes (Endendijk et al., 2017). However, using interviews on parenting ideals might reveal more details on beliefs about ideal parenting (Bar-On & Scharf, 2016).

Strengths and limitations

Although the current study has several merits, we also see some limitations. Beliefs about ideal mothers and ideal fathers were assessed using a Q-sort methodology with a fixed distribution of items. This has the advantage of a direct comparison of items regarding their relative salience for a person or an ideal, and controls for measurement error resulting from differing individual distributions and the effects of social desirability (Block, 1978). Our rationale was a close comparison with the Q-sort study on maternal ideals conducted by Mesman et al. (2016). However, when using a Q-set, items cannot be rated independently. Therefore, we suggest that future studies should also use questionnaires or interviews on ideal mothers and ideal fathers besides the Q-sort approach.

We only examined concurrent associations with attachment variables. We suggest studying the stability and change of parenting ideals for mothers and fathers longitudinally and examining potential influences over time.

The participants in this study were mainly Caucasian and highly educated, which limits the generalization of our findings. Future research may therefore investigate whether comparable results can be found in other samples with more diversity, as well as in other cultures.

The current study yielded some important and unique findings for research on mothering and fathering. This study directly compared representations of ideal mothers and ideal fathers using the identical methodology and including parenting dimensions that often have been studied solely with either mothers or fathers. The results highlight that both ideal mothers and fathers are expected to be highly sensitive and, at a medium level, also challenging. Our study also shows interesting differences and similarities between the ideal mother and father. The pioneering study by Mesman et al. (2016) provided important insights regarding the representation of solely female participants: one parent, the ideal mother; and one parenting dimension, maternal sensitivity. A clear strength of our study is the comparison of both parenting ideals in a sample of female and male participants regarding ideal mothers and ideal fathers. Thus, the results include the broader perspective of mothering and fathering, more facets of parenting, and male and female viewpoints.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Alexandra Iwanski: Conceptualization; Data Curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing - Original Draft; Writing - Review & Editing. Laura Mühling: Investigation; Methodology; Writing - Original Draft; Writing - Review & Editing. Peter Zimmermann: Conceptualization; Data Curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing - Original Draft; Writing - Review & Editing.