In recent years, the father´s role has progressively shifted from the idea of being a moral and authoritarian breadwinner to the notion of a caring figure, actively involved in childrearing. Today, in Peru, as well as in other Latin American countries, fathers tend to express their desire to be more involved in their children’s lives (Carrillo et al., 2016; Duarte et al., 2017; Izquierdo & Zicavo, 2015; Plataforma de Paternidades, 2016). However, these new beliefs about the role of the father, and their desire to be actively involved, have yet to be brought into families’ daily routines, since women's participation in unpaid work (domestic activities and caring for others - children or older people) continues to be much higher compared to men’s, who remain the main financial providers for their families (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, 2021).

Stereotypical beliefs regarding women and men’s gender roles are proposed as an explanation for the disparities found in the division of domestic and childcare activities. Mothers are still viewed as the natural primary caregivers, while fathers are seen as the economic providers (Karre, 2015). Such stereotyped beliefs, still prevalent in different socio-cultural groups, contribute to and validate men distancing themselves from childrearing (Aguayo et al., 2016), spending less time with their children, and being more involved in paid-work, financially supporting their families (Karre, 2015).

Culturally, mother’s roles are clearly defined, and viewed as mandatory, while father’s roles are less defined and more flexible (Parke & Cookston, 2019). For example, in Latin America, a father is seen as a figure that supports mother’s parenting or as mainly a playmate, with both men and women valuing the maternal role in women's lives (Ojeda & Ramírez, 2019). Parents in a Peruvian sample described the best organization regarding family and work life to be when mothers stay at home to take care of the children and do domestic activities, while fathers work full-time to earn money to support the family (Instituto de Opinión Pública, 2014). However, when mothers work outside of the home, they are still the ones who take care of the children, especially if the child is under six years of age (Bianchi, 2009). This disproportion is not necessarily just because men do not wish to share childcare activities, but can also be associated with women's difficulty in giving up traditionally assigned roles, and acting as gatekeepers (Schoppe‐Sullivan et al., 2015).

The home/family is a context where mothers traditionally have had more control and power, compared to the workspace, so mothers tend to sustain these traditional roles (Lamb & Tamis-Lemonda, 2004; Valdés & Godoy, 2008), even at a cost to their physical and emotional health (Lamb & Tamis-Lemonda, 2004). These rigid gender role discourses are more frequently present in low-income fathers, while more educated and high-income fathers tend to have more equitable beliefs. However, despite being more progressive, they do not necessarily participate more actively in child-related activities (Plataforma de Paternidades, 2016). Considering this context of gender inequality in which fatherhood is embedded, and the fact that previous studies have focused mainly on Caucasian and middle-class fathers in westernized countries (see Diniz et al., 2021 for review), little is known about what promotes or hinders paternal involvement in Latin America in general, and in the Peruvian context in particular.

Father´s involvement

Father involvement can be described as the degree of father´s participation in childrearing (Pleck, 2010). Several models (e.g., Cabrera et al., 2007, 2014; Lamb et al., 1985, 1987; Parke, 1996, 2000; Pleck, 1997, 2010) have been proposed to systematically define and explain paternal involvement. Parke, in particular (Parke, 1996, 2000), has highlighted the importance of distinguishing between contexts of involvement: Direct care, which involves direct interaction with the child (e.g., bathing); Indirect care, referring to managerial tasks that do not require interaction with the child (e.g., packing a diaper bag); Teaching activities, which refers to teaching new skills and competences (e.g., teaching the alphabet); Play activities, referring to playful activities with the child (e.g., playing in the garden).

Fathers and mothers do not seem to share these contexts/activities equally. Studies have shown that mothers are usually the ones engaged in direct and indirect care (Cabrera et al., 2000; Lamb & Lewis, 2010; Monteiro et al., 2017; Torres et al., 2014). For example, a study in Chile showed that only a third of the participating fathers reported being responsible for direct care (Aguayo et al., 2016). This division is observed even in families where mothers work outside of the home the same number of hours as fathers do (Lamb & Tamis-Lemonda, 2004). Play, in particular, has been considered, by some authors, as the most relevant context of paternal involvement for the preschool years (Jia & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2011). In fact, several studies report that fathers tend to be more involved in this type of parenting activity than in caregiving (Beitel & Parke, 1998; Buckley & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2010; Craig, 2006; Monteiro et al., 2019; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2013; Torres et al., 2014). Evidence also shows that fathers tend to interact differently. Compared to mothers, they display more humor and spontaneity; their play is more active, physical, or rough and often encourages children to explore and take risks (Amodia-Bidakowska et al., 2020; Cabrera & Roggman, 2017).

Additionally, Creighton et al. (2015) found that (as socially expected by masculinity standards) fathers tend to engage in outdoor activities and use play to construct a relationship with their children. According to fathers, these activities are not only contexts where they can teach and promote the development of children’s skills, but also help them to acquire different cultural norms. Also, for more traditional fathers, it can be a way of supporting mothers - the primary caregivers - by keeping the children entertained and giving mothers spare time for other activities. The ecological model of father-child relationships (Cabrera et al., 2007, 2014) proposes that paternal involvement develops in a dynamic system based on reciprocal relationships between father’s involvement and his characteristics (e.g., biological and cultural factors, personality, rearing history); their family’s characteristics (e.g., child’s sex, mother’s work status); and contextual, cultural, political, and economic characteristics (e.g., social support, family’s SES).

The model assumes that these characteristics interact, over time, in reciprocal processes, influencing direct and indirectly, how fathers interact with their children. For example, regarding family characteristics, child’s sex (e.g., Manlove & Vernon-Feagans, 2022; Planalp & Braungart-Rieker, 2016; Yeung et al., 2001), and age (e.g., Kulik & Sadeh, 2015; Torres et al., 2014) seem to have an impact on paternal involvement, with fathers being more involved with their children when they are boys, and older. Whereas the mother’s work status and the number of working hours, also show a positive association with father’s involvement (e.g., Maroto-Navarro et al., 2013; Meteyer & Perry-Jenkins, 2010; Torres et al., 2014). Fathering is also shaped by the influences of the workplace, social support networks, and socioeconomic status (SES). For example, SES is both positively (Gomes & Alvarenga, 2016; Jessee & Adamsons, 2018; Kulik & Sadeh, 2015), and negatively (Ishii-Kuntz, 2013; Kato-Wallace et al., 2014) associated with father involvement.

The present study, following the ecological model of father involvement (Cabrera et al., 2007, 2014), aims to explore, in a Peruvian sample, if father´s rearing history, and his age and education, are associated with his involvement in child related activities.

Father´s rearing history

There is an argument that fathers/mothers raise their children in a way that is similar to how they were reared; so it can be proposed that the nature and quality of parenting are transmitted intergenerationally (Belsky et al., 2009). According to this view, the quality of fathers’ early experiences with their own parents is described as a determinant of fathers’ involvement with their children (Cabrera et al., 2007, 2014; Parke & Cookston, 2019). Nonetheless, Parke and Cookston (2019) sustain that the evidence supporting this proposal is “complex and by no means clear-cut” (p. 86).

The research on this topic has been guided by two hypotheses. The first is the modeling hypothesis based on Bandura's social learning theory, which posits that fathers have their own fathers as their parental model. Thus, fathers’ parenting is shaped by the quality of relationship they had with their own fathers. Gaunt and Bassi (2011) consider that it is more common for fathers to model their parenting based on their own fathers´ characteristics, than on their mothers’. Jessee and Adamsons (2018) found that when men described having a positive relationship with their parents (during childhood), it was easier for them to form a high-quality relationship with their own children, due to their positive memories. Similarly, Kulik and Sadeh (2015) found a positive correlation between fathers childhood experiences with their fathers and their own involvement in their children´s care. According to Hall et al. (2014), fathers who reported having experienced more care and less overprotection/control with their own parents, reported more emotional bonding with their children during the first year of life. A different approach is the compensatory hypothesis, where fathers would reject their experiences lived with their own fathers when these were negative, and try to compensate for the lack of involvement and quality by being more involved (Parke & Cookston, 2019).

A study with kibbutz father-son dyads showed a more complex picture, with both modeling and compensatory processes being present. In other words, fathers tended to imitate their fathers´ high involvement in socioemotional care and compensated for their low involvement in physical care and responsibility (Gaunt & Bassi, 2011). Scarce research has been carried out on the modeling and compensatory hypotheses in Latin American contexts, with only one study involving Latin American fathers (Chilean and Mexican) found (Kato-Wallace et al., 2014). In this study, no associations were found between fathers’ involvement in direct care and play, and the way they were raised, either in a more traditional male role model, or in a more modern approach to parenting.

The context of today’s parenting, with growing expectations and changes towards a more involved and nurturing father, can make it less clear for them to replicate what they have experienced during childhood, namely if this was a traditional model. Nevertheless, it also gives them opportunities and models to do it differently. According to Parke and Cookston (2019), fathers have an active role in how they parent and in the models they use, both from past and current relationships. Therefore, the intergenerational transmission of parenting should not be viewed as a passive process, and it is also shaped by the context in which it develops. Research about this topic in the Latin American context is therefore necessary.

Father´s sociodemographic characteristics

Regarding father’s sociodemographic characteristics, studies have found a positive association between father’s involvement and his age (Castillo et al., 2011; Monteiro et al., 2017). Younger parents may be less emotionally mature and less open to identifying and understanding their roles and responsibilities than older fathers (Castillo et al., 2011). Other studies, however (Hayward-Everson et al., 2018), have not found any associations. Father’s education is also an important factor regarding parenting, and particularly paternal involvement (Beitel & Parke, 1998; Monteiro et al., 2019; Paquette et al., 2000; Santos et al., 2021). Fathers tend to be more involved with their children when they have had more education. Nemet et al. (2021) found that father's education positively predicts his level of involvement in housework and activities related to school and leisure. As more educated parents have access to more information about their children's needs, they feel more confident and motivated to be involved in their care.

Aims of the study

The present study has two aims, firstly, to compare the father’s relative involvement to the mother’s in child related activities (e.g., direct care, indirect care, teaching/discipline, play and outdoor leisure), in a group of Peruvian fathers with preschool age children. Based on previous literature (e.g., Beitel & Parke, 1998; Buckley & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2010; Craig, 2006; Monteiro et al., 2019; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2013; Torres et al., 2014), it is expected that fathers would be more involved in play/leisure activities, compared to direct and indirect care. The second aim is to test if father’s rearing history (father’s representations of care and overprotection/control from his mother and father) and father´s sociodemographic characteristics (age and education) were predictors of his involvement in childrearing, after controlling for covariates. According to the modeling hypothesis, it would be expected that the quality of the relationship that fathers had with their own fathers and mothers would be positively associated with their involvement with their own children. Whereas, according to the compensatory hypothesis, it would be expected that fathers with more negative rearing experiences would be more involved in child related activities with their own children.

Method

Participants

Participants were 206 nuclear families with preschool age children from different Peruvian cities. Fathers’ ages ranged from 21 to 59 years (M = 37.52, SD = 6.91). The average sum of education years was 16.18 years (SD = 2.70) - 10.70% had high school education, 60.70% had a university degree, and 27.70% had postgraduate education. Most fathers (95.60%) worked full-time jobs. Mothers’ ages ranged from 21 to 48 years (M = 34.09, SD = 5.60). The average sum of education years was 16.19 (SD = 2.88), with 16% having a high school education, 55.80% a university degree, and 25.70% postgraduate education. Sixty-eight percent of the mothers had a full-time job. Children’s ages ranged from 36 to 77 months (M = 53.94, SD = 10.41), 57.30% were female, 58% had siblings. All children attended preschool education centers. Families’ SES ranged from high to low: 5.3% were from high SES, 68.4% from upper-middle SES, 23.8% from middle SES, and 2.4% from low SES. Family’s socio-economic status (SES) was measured considering the characteristics (e.g., education level, work status) of the person who contributed the highest income to the household, as well as the neighborhood´s characteristics (e.g., urban or rural area), household´s characteristics (e.g., number of bathrooms, appliances in the house) (IOP, 2017), in a 5-point rating scale ranging from high to very low SES.

Procedure

The study was conducted according to the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (Opinion N° 0231-2016/CEI-PUCP). It is part of a larger project, aiming to study father involvement, its associated factors, and relationships with children’s social and emotional competence during the preschool years.

Data collection was carried out between 2017 and 2018 in fourteen educational institutions. All fathers and mothers were informed about the main objective of the study, and those who voluntarily agreed to participate signed an informed consent form before completing the set of questionnaires. Fathers completed the questionnaires referring to SES, father involvement, and rearing history; while mothers completed a sociodemographic data questionnaire (child´s, mother´s, father´s, and family´s characteristics).

Measurements

Father involvement. Fathers reported their involvement in relation to the mothers’ using the Spanish version of the Father Involvement Scale: Care and Socialization Activities (Monteiro et al., 2008). The questionnaire assesses the father’s perception of his own involvement in childcare and rearing activities, in relation to that of the mother. According to the questionnaire’s psychometric validation carried out in a Peruvian sample (Nóblega et al., 2022), it consists of 18 items organized into five domains: (1) Direct care (5 items), related to care tasks involving direct contact and interaction with the child (e.g., “Who bathes your child?”); (2) Indirect care (4 items), related to activities associated with how resources are organized to be available to the child that do not necessarily involve interaction (e.g., “Who attends your child’s education center meetings?”); (3) Teaching and Discipline (3 items), related to teaching skills and rules to the child (e.g., “Who sets the rules at home?”); (4) Play (4 items), related to playing activities between the child and the father (e.g., “Who plays with your child?”); and (5) Outdoor leisure activities (2 items), conducted with the child outside the home (e.g., “Who takes your child to the park?”). Fathers answered on a 5-point Likert-like scale (1 = “always the mother”; 3 = “both mother and father”; 5 = “always the father”). Higher scores represent a higher father involvement relative to the mother. All domains reached an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha coefficient: Direct care = .70; Indirect care = .67; Teaching and Discipline = .74; Play = .69; and Outdoor leisure activities= .63.

Father´s rearing history. Fathers also answered the Parental Bonding Instrument (Parker et al., 1979) translated into Spanish by Olivo (2012). It aims to assess what parents remember about their bond with their primary caregivers during the first 16 years of their lives. It consists of two questionnaires of 25 items each, which assess the bond with their mother and father, separately. The items are distributed in two subscales: (1) Care (12 items), related to the perception of having or not having a father/mother who expressed affection, warmth, empathy, and intimacy (e.g., “He/She spoke to me in a friendly, warm voice”); and (2) Overprotection/Control (13 items), related to the perception of father/mother’s psychological control, rigidity, overprotection, intrusiveness, and reinforcement of psychological dependence (e.g., “He/She tried to control everything I did”). Fathers answered on a 4-point Likert-like scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 4 = “strongly agree”). All dimensions reached a satisfactory Cronbach’s alpha level: mother’s care = .84; father’s care = .89; mother’s and father's overprotection/control scales = .72.

Data Analysis

Preliminary descriptive analyses were performed, in addition to one-sample Student’s t-tests to compare the mean values of father involvement with the value of 3 (representing the equal division of the tasks between fathers and mothers). Additionally, bivariate product-moment correlations were also carried out between father involvement, father´s rearing history, father’s sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, education level - work was not included since around 96% of the fathers worked), and family’s sociodemographic variables (child´s age, sex, and number of siblings; mother´s age, education level, and work status; and family SES). Lastly, multiple Ordinary Least Squares - OLS regressions analyses were conducted for each of the five father involvement domains, with father´s sociodemographic variables (e.g., age and years of education) and father’s rearing history as independent variables, while controlling for significantly associated variables to each dimension as covariates (child’s sex, age, and number of siblings; mother’s age, work, and education; family’s SES). For each dimension of father involvement, only significant correlated covariates were introduced in the model.

Results

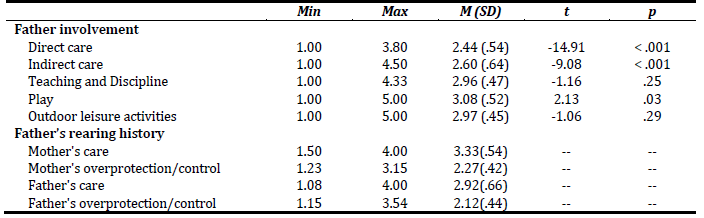

Preliminary descriptive analyses were performed for father involvement and father’s rearing history. In addition, the differences between the sample means for each domain of father involvement and the value of 3 - which corresponds to an equal sharing of the parental tasks in that domain (“both the mother and the father”), were also tested using one-sample Student’s t-tests. The results are presented in Table 1. Mean values of father involvement in Direct and Indirect care were significantly lower than 3, meaning that mothers were more involved in these domains. While mean values of father involvement in Play were significantly higher than 3. In other words, fathers were more involved in play activities than mothers. For Teaching/Discipline and Outdoor leisure activities, there were no significant differences: both parents tended to be equally involved in these activities.

Table 1 Minimum, maximum, mean and standard deviation for father involvement and father’s rearing history; and one-sample Student’s t-tests to value of 3 for father involvement

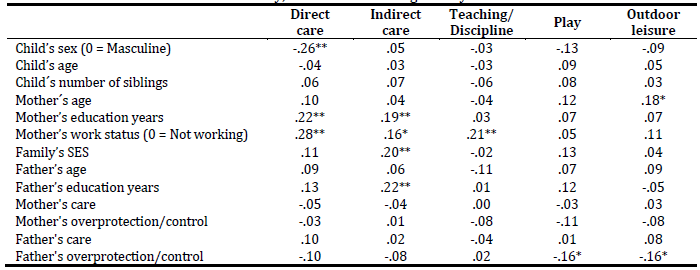

Correlations between the domains of father involvement, father’s and family’s sociodemographic variables, and father’s rearing history were tested through Pearson correlations. Results are presented in Table 2. Fathers were more involved in Direct care with their sons, and if the mothers were employed and had a higher education level. Whereas fathers were more involved in Indirect care when mothers and fathers had a higher education level, family’s SES was higher, and when mothers were employed. Fathers were more involved in Teaching/Discipline when mothers were working. For the Play model, fathers were more involved in Play activities when they perceived their fathers as less overprotecting/controlling. Lastly, for Outdoor leisure activities, fathers were more involved when mothers were older, and when fathers perceived their fathers as less overprotecting /controlling.

Table 2 Correlations between father´s involvement in childcare activities, sociodemographic characteristics of the father and the family, and father’s rearing history

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01

To explore whether father involvement was predicted by father’s sociodemographic characteristics and father’s rearing history, multiple OLS regressions were performed for each dimension of father involvement (while controlling for covariates). The summary of the models is presented in Table 3. The model for father involvement in Direct care, F(9, 190) = 5.48, 𝑝 < .001, 𝑅 𝑎 2 = .17, reached significance, with child’s sex, 𝛽 = -.28, p < .001, mother’s work status, 𝛽 = .29, p = < .001 and father’s perceptions of their mother’s care, 𝛽 = -.16, p = .03, proving to be significant predictors. For Indirect care, the model was significant, F(9, 175) = 1.95, p = .048, 𝑅 𝑎 2 = .04, however no significant predictors were found. The model for Outdoor leisure, F(7, 196) =2.37, p = .024, 𝑅 𝑎 2 = .04, was also found to be significant, with mother´s age, 𝛽 = -.17, p = .04, and father's perceptions of their father’s overprotection/control, 𝛽 = .24, p = .01, as significant predictors. The models for Teaching and Discipline, F(7, 198) = 1.73, p = .054, and Play, F(6, 199) = 1.66, p = .132, were not statistically significant.

Discussion

The first goal of the study was to describe father involvement (in relation to the mother) in child related activities that occur in daily family life, in a group of Peruvian fathers. As expected, fathers were less involved than mothers in children´s direct and indirect care, with mothers being “almost always the ones” engaged in childcare, and fathers acting as the helping hand (e.g., Aguayo et al., 2016; Kotila et al., 2013; Maroto-Navarro et al., 2013; Monteiro et al., 2010; Monteiro et al., 2019). In play, fathers tended to be more involved than mothers (Monteiro et al., 2019; Torres et al., 2012), while in teaching/discipline and in leisure activities outside, fathers were as involved as mothers (Amaral et al., 2019; Monteiro et al., 2019; Torres et al., 2012). Although studies have shown that fathers want to participate more in their children’s lives (Carrillo et al., 2016; Duarte et al., 2017; Izquierdo & Zicavo, 2015; Plataforma de Paternidades, 2016), in our sample, they still seem to be organized around traditional gender roles when it comes to care activities. In fact, this was described as typical in Latin American contexts (Instituto de Opinión Pública, 2014; Ojeda & Ramírez, 2019). Discussion on whether this has changed, and how much, in recent years, is impossible due to the absence of previous research in Latin America. There may well have been a change and fathers are more involved with their children, and that fathers’ participation may have been even lower in the past.

A note regarding the characteristics of this sample: fathers were well educated and upper-middle class. Our results are similar to the ones reported by the Plataforma de Paternidades (2016) showing that in Peru more educated and high SES men also tend to have low participation in childrearing, regardless of their attitudes towards domestic labor. Even more, this traditional configuration was present in families where 68% of the mothers had a paid job outside the home, which indicates that although women work, they are still the main caregivers, as in other samples across Europe and the USA (Bianchi, 2009, Diniz et al., 2021). The quality of employment is low in most Latin American countries, e.g., in Peru, 18% of the active economic population have two jobs (INEI, 2020), and more than 30% work 49 or more hours per week (Ministerio de Trabajo y Promoción del Empleo, 2022), with men being the main providers for their families. These working conditions may not facilitate father involvement due to the lack of time left to share with family and children. In this context, is more likely that fathers will invest in activities that are more fun, and less bound by strict schedules, as well as being in line with traditional gender roles.

Additionally, this study aimed to understand if fathers´ early experiences and sociodemographic variables (age and education) were predictors of their involvement in child related activities. Results of the regression models showed that fathers´ participation in direct care was negatively predicted by fathers’ representation of their mother´s care. Fathers who remembered having received fewer care from their mothers were more involved in direct care with their own children. According to the compensatory hypothesis (Parke & Cookston, 2019; Pleck, 1997), these fathers would be compensating for the perceived poor care from their mothers, by becoming more involved fathers, and promoting healthier relationships with their own children. This may be facilitated by the current views on father’s roles (McFadden et al., 2009). Interestingly, the rearing experiences with their fathers were not significant, contrary to other Latin American studies (Ishii-Kuntz, 2013; Jesse & Adamson, 2018; Kato-Wallace et al., 2014; Kulik & Sadeh, 2015). Other variables, such as psychological characteristics, gender-role beliefs, or social support could explain this result (Bouchard, 2012; Belsky et al., 2009), and should be included in future studies.

Results regarding the leisure outside model found fathers’ representations of their fathers’ overprotection/control to be a significant predictor of paternal involvement in this domain. Fathers who remembered having experienced less overprotection or control from their fathers were more involved in recreational activities outside the home. This result was expected, since the absence of overprotection or control in the relationship with their father is an indicator of fathers’ emotional availability, which could be reproduced in the relationship with their own children (Belsky et al., 2009). In addition, the father role is often associated with the role of a ‘play partner’, characterized by physical, challenging, and stimulating interactions (Grossmann et al., 2002; Lamb & Lewis, 2010), with the father providing emotional, affective, and exploratory support (physical and social). Hence, following the modeling hypothesis, fathers who experienced less overprotection/control (and more encouraging of risky behaviors and exploration), would model these behaviors, and be more involved in potentially challenging outdoor activities with their own children.

Interestingly, the magnitude of significant correlations and explained variance of the models were low. Future studies might need to consider other variables to have a better understanding of father involvement, such as, father’s and family’s biological and psychological factors, family dynamics, social support networks, and cultural factors, (Belsky et al., 2009; Cabrera et al., 2014; Holmes et al., 2020). Specifically, regarding gender-based beliefs about the father, there is a need to integrate these theories, considering the specificities of diverse socio-culture contexts, in order to better understand the different mechanisms through which parenting characteristics are transmitted intergenerationally (Belsky et al., 2009). This is particularly significant when we aim to look beyond American or European samples, as many studies do.

This study has some limitations that need to be addressed. One is the cross-sectional research design. A longitudinal study would allow exploration of the trajectory of rearing history and subsequent father involvement. This was a convenience sample, and a larger and more diverse socioeconomic sample is also needed in the future. All measurements were self-reported, leading to potential self-report and social desirability biases. In addition, there were a number of biases related to the measurement of rearing history based on fathers’ retrospective reports: memory errors, such as omissions and false memories (Belsky et al., 2009), or the use of current experiences with parental figures to evaluate past experiences (Bouchard, 2012).

Nonetheless, several strong points can be identified, namely the focus on fathers and their perspectives. Moreover, to our knowledge, this is the first contribution to describing father involvement and its predictors, particularly regarding their rearing history, in a group of Peruvian fathers, and can be used to inform interventions to promote fathers’ participation in childrearing, as well as other family policies. The results show the need to strengthen these initiatives due to the low participation of the father in childcare activities and the traditional view of the father’s and mother´s roles that seems also to prevail in Peru. A more egalitarian distribution of childcare activities, as well as other household activities, would contribute to the well-being of adults and children, as well as to a more equitable society, in alignment with the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Magaly Nóblega: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Acquisition of financing, Research, Methodology, Resources, Oversight, Validation, Visualization, Writing of the original draft. Marisut Guimet: Conceptualization, Data retention, Formal Analysis, Acquisition of financing, Research, Methodology, Projects administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing of the original draft. Andrea Ugarte: Conceptualization, Data retention, Formal Analysis, Acquisition of financing, Research, Methodology, Projects administration, Resources, Validation. Francesco Marinelli: Conceptualization, Data retention, Formal Analysis, Acquisition of financing, Research, Methodology, Projects administration, Resources, Validation. Gabriela Apolinario: Research, Writing. Daniel Uchuya: Research, Writing. Carolina Santos: Writing.