Introduction

In Colombia, the object of study of gender research has involved a diversity of topics and phenomena. These issues converge in a central purpose: to transform androcentric knowledge and create a new one, which allows explaining the subordination of women and gives way to the gender perspective and the specificity of difference (León 2007). This purpose resulted in a knowledge that allows reading reality attending to the social dynamics of relations between the sexes, together with other social relations such as class, race or ethnicity (Caggiano 2012; Viveros 2013).

Gender studies in Colombia have become a specialized field of knowledge. The academic production derived from gender research has contributed to the transformation of the realities of subordination and domination (Rodríguez-Pizarro & Ibarra-Melo 2013). As a result, the topics and problems of knowledge within gender studies are worked upon to produce knowledge and action, which reflects a fundamental characteristic of feminist and gender epistemologies: knowledge should not be separated from action (Guzmán & Pérez 2005; Buchely 2013; 2014). Knowledge and action constitute two dialogical and integral dimensions present in the nature of gender studies in Colombia. These two dimensions have enabled it to become a vehicle for promoting spaces for citizen participation, legitimacy and political resistance (Parola & Linardelli 2021).

The particularities of gender studies in Colombia lead us to this article's thesis: there is a relationship between political and academic scenarios, woven from the debates opened by feminist groups and the boom in gender studies leveraged by research groups in universities. This issue has opened up the possibility of the invention of tradition (Hobsbawm & Ranger 1983). In the particular case of gender studies in Colombia, they correspond to the legitimizing fact of the processes of indigenous vindication of women and the LGBTI population of each region in the country, in the light of human rights, citizenship and democracy (Estrada 1997; Jurado 2016; Rodríguez-Amat & Jeffery 2017; Gil-Hernández & Pérez-Bustos 2018).

To support this thesis, we present a historical review that provides elements to understand how the field of gender studies was forged in the country from the first social mobilizations and feminist struggles that took place in different scenarios of the national territory. Secondly, we present some conceptual resources that allow us to discuss the relationship established between knowledge and action in order to understand in greater detail the nature of gender studies in Colombia as a dynamic resource for the collective action of social groups. Thirdly, we present an analysis of academic production in gender studies in Colombia based on an empirical corpus extracted from a database with citation and bibliographic information (Scopus).

Historical elements for gender studies in Colombia

At the beginning of 20th century, substantial changes began to appear in the country's social structure due to the expansion of coffee production and the increase in the monetary economy of the rural sectors that led to processes of labor migration to the large cities (Salas-Díaz 2015). During this time, the construction of new patterns of intimacy, different from those of the traditional peasant family, became evident (Estrada 1997).

This shift in the intimacy patterns and roles of the traditional Colombian family precedes the Thousand Days War. In 1899, this war resulted in the death of approximately three hundred thousand Colombian citizens (Bermúdez 2014). As a result of the war, Colombia's agriculture was impoverished and widows were forced to migrate to the cities. One of the events that significantly marked the entry of women into the world of work was the 1907 decision by the Coltejer textile factory in Bogotá to hire a large number of women. However, the precarious conditions in the companies did not guarantee Colombian women a decent job, and any attempt to protest was immediately repressed (Arango 1991; Bermúdez 2007).

This period of contingency and crisis in the institutions of the country created the necessary conditions for the emergence, in the 1920s, of the first feminist groups in Colombian history. Their actions were designed to achieve the fulfilment of political and civil rights in education, health, work and moral reform (Franco-Giraldo & Álvarez-Dardet 2008; González 2011; 2014; Bello-Urrego 2013; Huertas & Hernández 2016). In 1919, the peasant Juana Julia Guzmán founded the Sociedad de Obreras Redención de la Mujer in the municipality of Córdoba. This movement aimed to regulate the work of women and minors, who were being exploited (Reyes & Saavedra 2005; Velazco 2014). In the same year, the socialist party was founded following the continuous workers’ protests led by 400 women against social injustices. In addition to supporting the strike in Bello (Antioquia), more than 400 women fought against injustices (Garcés 2013). These actions managed to transcend the precarious conditions and begin a struggle for the vindication of human rights within the social and institutional spheres of Colombian women at the time.

These events allowed feminism to find an important foothold for starting its political struggle in Colombia. By 1926-1927, Susana Olózaga de Cabo and Ana Restrepo founded the journal Anthena to promote the struggle for women's rights (Cohen 2001). María Rojas Tejada and Baldomero Sanín Cano actively participated in the debates on the condition of Colombian women, organizing and convening a conference on feminism in 1927 in the city of Pereira (Luna & Villareal 1998). In the same year, the National Pedagogical Institute was created to carry out academic and professional training for women. Also in the same year, some 14,000 indigenous women signed the manifesto for the Rights of Indigenous Women in Colombia (Buitrago 2013). One of the milestones in the vindication of women's rights in Colombia was the admission of women to university in 1935 (Ramírez 2010).

Between 1954 and 1957, under the government of General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, the movement of “suffragettes” led by Esmeralda Arboleda and Josefina Valencia arose to fight in the National Constituent Assembly for women’s right to vote without any restrictions (Ariza 2014). A foundational milestone was the election of Arboleda as the first woman in the Senate of the Republic (Luna &Villareal 1998). The organizational process of women continued in the 1960s, when women's collectives and social movements played a definitive role in showing the inequality that women faced in accessing economic, social and cultural rights (López & Güida 2002; Lurent 2009; Gomes-Maciazeki, Nogueira & Filgueiras-Toneli 2016).

In the mid-1990s, the first gender research groups emerged in the country, a fact that can be linked to the establishment of the National Constituent Assembly that gave rise to Colombia's political Constitution in 1991, which declared the country to be a social, multi-ethnic and multicultural state under the rule of law. The Constitution gives priority in its articles to the defense of equality and non-discrimination on the grounds of sex, race, age, religious or philosophical beliefs (Political Constitution of Colombia, Article 13).

Thus, the academy enters the scene, and intellectual production on the subject, no longer isolated, begins to emerge and become established within the universities and research groups. Currently, 12 research groups in the field of gender studies are registered in MINCIENCIAS.1 These groups include an important number of researchers specialized in gender studies in the country.

Next, let us look at some elements that allow us to discuss the relationship established between knowledge and action in the framework of gender studies in Colombia.

Knowledge and collective action in gender studies in Colombia

Gender studies in Colombia have found a critical bridge to think about the impact of research in diverse scenarios and social collectives (Daza 2015; Buchely, Castro & Uribe-Vásquez 2021). A close dialogic relationship is established between the dynamics of research, academic production and civil society (Ziman 2003). Specifically, Colombian gender studies, which have developed over the last two decades, converge with social, political, historical and economic processes in the country. Among these processes are: The 1991 Constitution; the peace process recently signed with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which gave a particular emphasis to the inclusion of the gender perspective; and important political and legal debates, such as equal marriage and adoption by same-sex couples, to name a few significant milestones.

The gender studies’ approach in the promotion of conditions for collective action provides a framework for the complexities and social realities of the country, where this field opens up spaces for reflection, debate and political struggles. Among these, we can include the actions of women, marginalized social groups, ethnic communities, the struggle for human rights, the search for dignity and peace (Bonilla-Vélez 2007; Millán et al. 2020a). Collective actions have been used as a tool that can contribute to social change and the development of a community, fostering peace processes (Sánchez-Mora & Rodríguez 2015). Collective action has been used as a mechanism to address various issues of interest, such as injustice, government mismanagement, knowledge of the conflict, as well as to work through activities to resolve a particular problem of a group or population (Ibarra-Melo 2007; 2011a).

Approaching collective actions in the framework of gender research implies carrying out a critical reading of the social, cultural, historical and political complexities to unveil how this set of conditions and circumstances is articulated (Ibarra-Melo 2015; Bonavitta 2016). Gender research focuses on recognizing the importance of the political context where collective actions take place. The relationship between knowledge and collective action creates the conditions for the formulation of demands to expand democracy and its representation in state institutions (Luna 2003).

As we have explained, in the Colombian context, collective actions have been a vehicle for mobilization, among many others, to incorporate demands for abortion rights, sexual and reproductive rights, the elimination of violence against women, and the recognition of equity and equal rights (Ibarra-Melo 2011b). This type of activism constitutes a source of knowledge within the framework of gender research in Colombia.

The academic production in gender studies in Colombia is based on its articulation with processes and dynamics of emancipatory collective action. Emancipation represents a social process carried out by forces that resist and come into tension with a system of oppressive logics (Nash 2006). Therefore, in this study, we argue that gender studies in Colombia have demarcated an important link between political and academic settings. These two settings represent two knowledge-generating dimensions within research that have led gender studies to become a specialized discipline in both socially committed and transformative terms (Rodríguez-Pizarro & Ibarra-Melo 2013; Barranquero & Ángel 2015). In order to delve deeper into the relationship between the country’s socio-political development and the emergence and growth of gender studies, the findings of the socio-bibliometric analysis to determine consumption indicators and content analysis to identify lines of research in gender studies in the country are presented below.

Method

An analysis of the academic production in gender studies in Colombia was carried out to provide a brief overview of this production in the country, using the socio-bibliometric method. The methodological framework focuses on articulating the analysis of academic production with historical, social and political events that have forged the field of gender studies and its multiple lines of research in Colombia. This perspective seeks to achieve a greater understanding of the data produced by academic production in light of the historical events that underlie these research dynamics (Millán, Polanco, Ossa, Beria & Cudina 2017; Polanco, Beria & Klappenbach 2017).

Corpus

The empirical corpus of the study consists of the academic production in gender studies recorded in the Scopus database. The Boolean term OR was used in the following descriptors: Gender, Gender studies, Gender violence, Theory of gender, and Feminism in titles, abstracts and keywords. The sample consists of 1328 articles, which were used for data extraction and analysis. The articles recorded in the database cover the period from 1976 to 2017, and are indexed in the social sciences. Only articles published by authors affiliated with Colombian national universities were considered for the study. Each paper was reviewed, taking into consideration basic information, including authors, institutions and countries.

Procedure and analysis

Once the empirical corpus was constituted, academic production and social network analysis indicators were presented (Millán et al. 2020b). The graphic representations of the conceptual network derived from the co-occurrence analysis correspond to the empirical corpus of data incorporated in the Vosviewer 1.65 program (van Eck & Waltman 2010). The system of categories to identify and classify the thematic lines of research of the academic production in gender studies in Colombia was carried out, taking into account the historical study of Estrada (1997). This study presents 10 lines of research that have historically shaped the progress of gender studies in the country. From a co-occurrence analysis of the empirical corpus of our study, it is possible to show the emergence of other categories that translate into the appearance of three new lines of research. In total, thirteen lines of research are formed from the revision of the empirical corpus (see Figure 5 in results).

Results

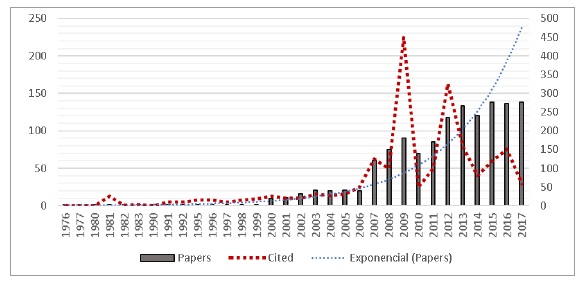

Reviewing in detail the corpus of academic production in gender studies in Colombia provides relevant data. One of them has to do with the historical line of development of research in this field, based on the academic production, as shown in Figure 1. The earliest studies were recorded in the period 1976-1977, and from then on there was a steady increase in production until 1999. During those 23 years, 1.7% (n= 23) of the academic production in “gender studies” recorded in the country was published.

Figure 1 Historical line of academic production in gender studies in Colombia. Source: Authors’ compilation, based on data from Scopus (2018).

During the first decade of the years 2000, 31.1% (n=413) of the academic production was recorded. However, it is from 2010 onwards that this increase shows an exponential growth. In the period 2010-2017, 67.2% (n=892) of the academic production in gender studies in Colombia is registered.

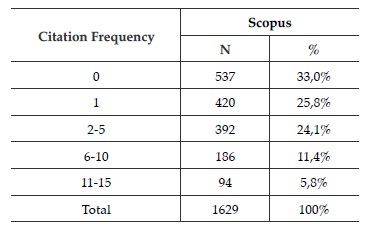

On the other hand, the citation rate recorded in general terms shows a low indicator. A significant portion of this production (33.0%; n=537) has never received a citation, while 25.8% (n=420) has been cited only once. Table 1 shows the citation frequency of the academic production in gender studies according to the Scopus database.

The citation frequency begins to have a significant behavior from 2-5 and 6-10 citations per paper. These frequencies account for 35.5% (n=578) of the citations registered within gender studies in Colombia. Concerning the authors registered, we find a total of 372 social science researchers who have been shaping the field of gender studies in Colombia. Figure 2 shows the network of authors who have contributed at least two research papers published and recorded in the database.

The network reveals the communities formed from the collaborative work that is woven between national and international researchers. The map shows the formation of at least ten cooperative work niches within gender studies in Colombia (Adams, Chiang & Starkey 2001). It is also evident that research in gender studies in Colombia is not marked by a dynamic governed by co-authorship (Cronin 2001).

The communities that can be highlighted include the works of Lina María Uribe Tirado (Red Cluster); Lina María Saldarriaga, Luz Stella López (Blue Cluster); Carmen Lucia Curcio (Yellow Cluster); Daniela Salazar, Francisco José Ruiz (Violet Cluster). It is essential to mention that the cooperation feature is marked by cross-cultural studies and the validation of instruments where gender constitutes a fundamental dimension. Work on gender theory has been carried out by authors such as María Eugenia Ibarra-Melo, Lina Fernanda Buchely, Ana L. Jaramillo-Sierra, Tania Pérez-Bustos, Laura Maria Uribe Forero, Ana Patricia Pabón Mantilla, Angela M. Estrada, Isabel Cristina Jaramillo, Helena Alviar and Julieta Lamaitre.

Figure 3 presents the co-authorship networks formed from collaborative work within gender research in Colombia.

Figure 3 shows Colombian universities’ meaningful participation in gender studies within the country. Partly, this is explained by the fact these institutions forged the first gender studies centers and research groups. Such institutions include the Universidad del Valle, the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, the Universidad de Antioquia and the Universidad de los Andes. It should also be noted that Colombian universities in the private sector have been generating a line of work in gender studies. Among these universities are Universidad del Norte, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz, Universidad del Rosario and Universidad de Medellín.

Semantic map of gender studies in Colombia

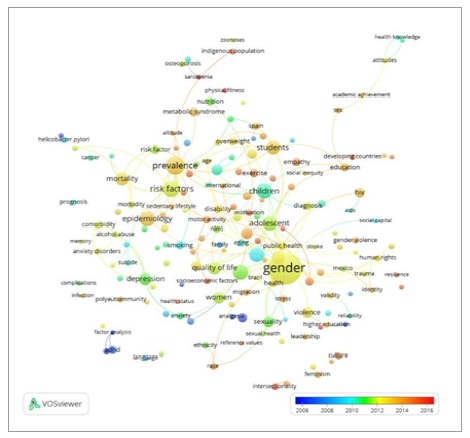

In reviewing the configuration of gender studies, one can see the emergence over the last ten years of different thematic lines, as shown in Figure 4, in the co-occurrence of the most important words in gender studies research in recent years.

Figure 4 Semantic map of gender studies in Colombia. Source: Authors’ compilation, based on data from Scopus (2018).

Figure 4 shows that, from the concept of gender (the most representative cluster), concepts such as public health, quality of life, risk factors and epidemiology are juxtaposed in a more significant way. At an intermediate level, and revealing a novelty, some concepts such as identity, social inequity, socioeconomic factors and human rights show in a less significant manner an orientation towards approaching gender studies from the perspective of law and economic equity. We can understand the concept of gender as a hinge concept, that is, capable of generating much more complex understanding of relations than when only one sociological variable is used to explain a phenomenon.

The concept of gender represents a development in the research process that has permeated the academic and research scene in Colombia, enabling the emergence and consolidation of academic communities that conduct research and produce in the field of politically relevant gender studies.

Thematic lines that constitute Gender Studies in Colombia

As we have mentioned, in the last two decades there have been ten thematic lines of research that have shaped and characterized gender studies in the country (Estrada 1997). Moreover, from the dynamics of research established during this period, at least three new research lines have emerged. These lines explore gender and health, children and adolescents, with a gender rights approach, and peace and post-conflict processes.

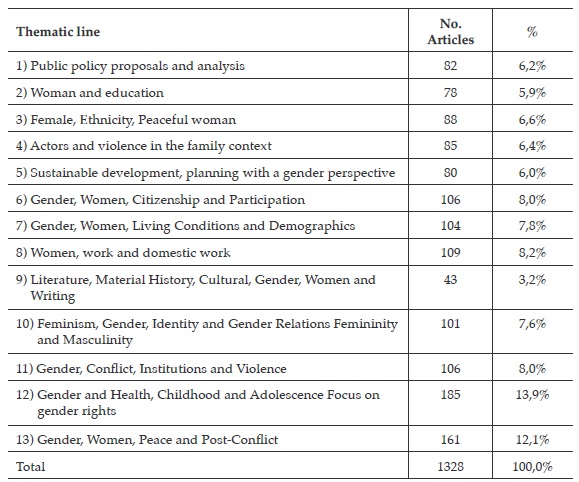

Figure 5 Thematic lines of gender studies in Colombia. Source: Authors’ compilation based on Estrada (1997).

Note: The number in parentheses indicates the thematic line presented in Table 2 below.

Table 2 shows the frequency of articles according to the gender studies thematic lines in Colombia over the last twenty years, with a clear increase in thematic lines and proportional to the exponential growth curve.

Regarding Table 2, it is important to note that a significant percentage of studies currently recorded are in the Gender and Health, Childhood and Adolescence, Rights-based approach thematic line, with 13.9 per cent (n=185). This is followed by the thematic line of Gender, Women, Peace and Post-Conflict, with 12.1% (n=161) of the academic production recorded in the last five years. There is a growing pace of academic production in gender studies, especially in the country's higher education institutions (HEIs).

Although the HEIs that stand out the most are those belonging to the official sector, in some private institutions there are also important developments in the field of gender studies. The most representative official sector institutions are Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Universidad del Valle, Universidad de Antioquia, Universidad de Caldas, and the private sector institutions are Universidad de los Andes, Universidad Javeriana, Universidad del Caribe and Universidad del Norte.

Limitations of the study

The analysis of the academic production in gender studies in Colombia was carried out with the information obtained from the Scopus database. It is assumed that the results presented in this study correspond to only a small sample of the scientific production in gender studies within the Colombian academic community. However, we recognize that there are other aspects, such as the diffusion and training in gender in the academic environment or publications of the so-called “grey literature”, which are not included in these databases. Therefore, this study opens a door for the realization of socio-bibliometric reviews in different databases that will allow us, as in a puzzle, to put the appropriate pieces together to configure a more precise and comprehensive field of gender studies.

Discussion and conclusion

The increase in academic production in gender studies is a phenomenon that has occurred in other countries, with the conformation of clearly forged thematic lines that reveal consolidated research dynamics (Ferreira, Vieira, Silveirinha, Carvalho & Freire 2020). However, the particularity of the gender studies thematic lines is related to central aspects of social and political conditions.

In the Colombian context, the thematic lines that are emerging in the dynamics of research within the field of gender studies are as follows: a) Gender, Conflict, Institutions and Violence; b) Gender and Health, Childhood and Adolescence, Focus on gender rights; and c) Gender, Women, Peace and Post-Conflict. These lines are representative of the volume of production in the last five years. We argue, based on the above, that gender studies in Colombia is a field driven by production dynamics within a national political context where social collectives play a preponderant role.

We hope that the current study can contribute to the development of comparative studies that allow for situating the discussions that are formed from the relationship between academic production and collective actions as two resources of analysis within gender studies in particular, and the development of socio-bibliometric studies in general. This study addressed the relationship established between the dynamics of academic production and social mobilizations within gender studies in Colombia. From the methodological point of view, socio-bibliometrics represents a novel resource that can be used to explore the progress of gender studies as a specialized field of knowledge, as well as to ask significant questions about the rationale of excessive growth in papers published by universities and institutions, which has resulted in an aimless academic production (Cadavid 2008).

This would allow us to pay attention to the approach of the thematic lines as an object of study in bibliometric research in the national and international political context. In this sense, we agree with Buchely et al. (2021), who argue that it is essential to begin to analyze the contexts of mobilization that contribute to the academic production of gender research in the country. Collective actions in the light of the socio-political events of the last five years in the country are so diverse that it is necessary to devise a working route to establish the differences and analogies of the impact of mobilization in strengthening the field of gender studies.