1. Introduction

In recent years, populist leaders have gained power in various countries, coinciding with the widespread use of technology in communication. This has led to an increase in violence against women, particularly on social media platforms, where misogynistic discourses are organised and amplified, turning into gendered disinformation campaigns (Cabañes 2020). While the definition of disinformation is still debated (Pepp, Michaelson & Sterken 2022), in this paper, “disinformation” refers to the deliberate spread of false information with the intent to cause harm or for profit (European Commission 2018; Wardle & Derakhshan 2018).

The rise of disinformation is linked to far-right discourse strategies in various countries, including Brazil, the United Kingdom, Turkey, the United States, and Russia, affecting events like the COVID-19 pandemic, Brexit, and the war in Ukraine (Engesser et al. 2016; Akgül 2019; Hjorth & Adler-Nissen 2019; Alcantara & Ferreira 2020; Brenner 2021; Faulkner, Guy & Vis 2021; Richards 2021; Recuero et al. 2022; Yablokov 2022). Despite increased attention to disinformation studies, particularly after Donald Trump's 2016 presidential victory (Freelon & Wells 2020), there is still much to explore in terms of how women and underrepresented groups are targeted and the long-term impacts.

This paper recognises the need to critically study gender-based disinformation and assess the extent of academic research on the topic. It reviews works on disinformation guided by the PRISMA protocol, considering Web of Science and Scopus databases while adopting an intersectional feminist perspective (Collins 2000; Crenshaw 2015). The findings reveal three recurring themes: women are frequent targets of disinformation, weaponised narratives link to “dark politics,” and proposed solutions continue to rely on media literacy programs and regulatory measures.

This study contributes to the emerging field of critical disinformation studies and works toward establishing a taxonomy of gender frames. It emphasises how women are targeted by harmful gender-based disinformation online, advocating for a critical examination of the phenomenon. This approach involves integrating critical gender and race studies and recognising intersectionality, rather than treating women as a homogeneous category of analysis.

2. Gender, disinformation and hate speech

Evidence highlights how disinformation frames gender stereotypes and misogyny (Sessa 2020). Women, especially those from marginalized groups, face online violence, censorship, and surveillance. High-profile women, including celebrities, politicians, gamers, feminist figures, journalists, and researchers (Marwick & Caplan 2018; Stabile et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2020; Murphy & Flynn 2022; Di Meco 2023), endure harassment, abuse, and disinformation campaigns. Aggressors exploit digital platforms to suppress and exclude voices, impacting democracy (Engesser et al. 2016; Habgood-Coote 2018). Democracies led by autocrats have shown an increase in the frequency of attacks against female public figures. Gendered disinformation portrays women as untrustworthy or too emotional for politics, and it harms female public figures' reputation and discourages women from participating in politics (Di Meco & Wilfore 2021). In this vein, Lucina Di Meco (2020, 4) defines gendered disinformation “as the spread of deceptive or inaccurate information and images against women political leaders, journalists and female public figures, following storylines that draw on misogyny and stereotypical gender roles.”

Historically, knowledge production served power structures to marginalize women and women of colour (Kuo & Marwick 2021). Social structures that produce and perpetuate social inequalities and violence have found new mechanisms to invalidate or exclude social minority groups through new digital technologies (Benjamin 2019). Hate speech targets individuals based on nationality, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, and gender, spreading quickly on digital platforms (Lapa & Di Fátima 2023). These structures have deep historical roots in segregating marginalized groups. Racist disinformation denies black identity and perpetuates stereotypes about black women (AzMina Magazine & InternetLab 2021). Gender conservatism in Latin America is rooted in colonial capitalism, denying autonomy to women, especially Black and Indigenous women (Rios & Lima 2020). In effect, white supremacy ideologies have gone mainstream since the ubiquitous presence of social media platforms in contemporary communication, as well as the emergence of far-right ideologies in the Western political landscape (Trindade 2018).

Research shows a wave of conservative movements in various geopolitical digital contexts. They share common structures with insurgent politics, including friend-enemy antagonism, latent masculinity, affinity for guns, misogyny, racism, homophobia, bigotry, Christian values, and violence as a societal sorting force (Waisbord 2018; Empoli 2019; Cesarino 2020). Digital media and politics have profound effects online and offline. Scholars believe new media can promote social change and alternative politics. Feminist digilantism (Jane 2016; Abidin 2018) involves performative responses to online attacks, such as parody, memes, and feminist humour to expose sexism and abuse (Lawrence & Ringrose 2018).

The digital world's freedom of expression has created impunity, blurring the line between online and offline violence. So, separating offline from online is often a mistake (Coding Rights & InternetLab 2017). Victims suffer from self-censorship, suicide, and a lack of support (Relly 2021). Digital platform policies and legislation play vital roles in combating gender-based online violence (Wilfore 2021; Amaral, Simões & Poleac 2022).

3. Research design

4.1 Research Questions

We conducted a systematic review of the literature guided by the following questions:

To what extent has gender-based disinformation been seen as a relevant study object in the academic literature from 2013-2023?

How does academic literature frame the scope of gender-based disinformation from 2013-2023?

What research opportunities and gaps can be leveraged to address and understand gender-based disinformation?

4.2 Corpus selection

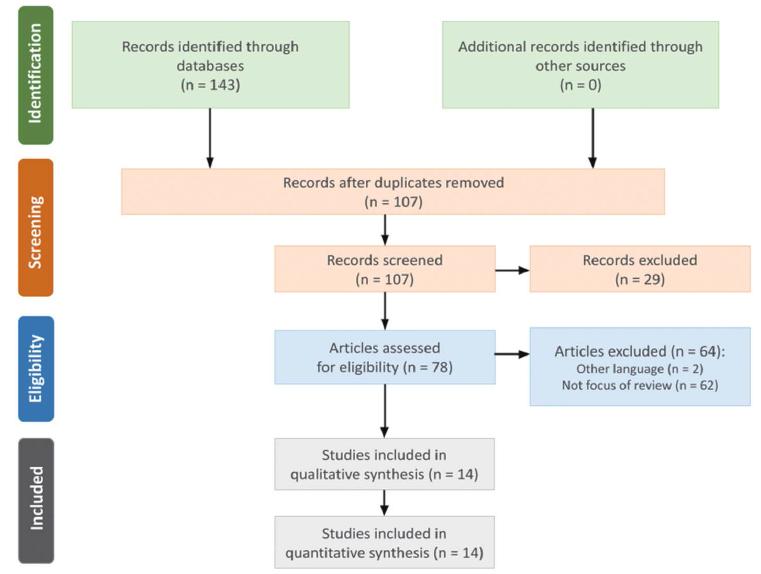

Following PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al. 2014) and a thorough keyword database search (Figure I), we conducted a two-stage search. The first stage focused on keywords - (“gender-based” OR “gendered”) AND (“disinformation”) - in Web of Science and Scopus. In the second stage, we added “gender” to the search terms: ("gender-based" OR "gendered" OR "gender") AND ("disinformation").

We chose to use Web of Science due to its data quality reputation (Martín-Martín et al. 2021; Visser, van Eck & Waltman 2021). This initial Web of Science search yielded 58 articles in February 2023. We also searched Scopus and found an additional 85 articles not present in the initial Web of Science search.

Out of the combined 143 articles from both databases, 108 were related to disinformation, even if they didn't explicitly mention “gender.” Web of Science contributed 49, and Scopus added 59. After removing duplicate publications, we had 107 unique studies. We excluded inaccessible articles (n=15), books (n=1), and conference proceedings (n=13), leaving us with 78 articles for eligibility assessment.

Our inclusion criteria considered language (Spanish and English), relevance to media and communication fields, and the use of gender as a research frame, not just as a demographic category. 64 articles did not meet these criteria and were excluded, resulting in the inclusion of 14 articles.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al. 2014. Available on www.prisma-statement.org. Last access in February 2023.

Figure 1 Information flow with the different phases of a scoping review

4.3 Coding analysis

The categorisation matrix was built from the data by the inductive-deductive method (Mayring 2000; Elo & Kyngäs 2008). The MAXQDA software was helpful in giving insights on categorisation and semantic relations to conduct the data analysis of the relevant literature. The analysis matrix includes seven variables: year of publication, methodological approaches (study methods and data analysis), country/territory of study, country/territory of the institution, research focus, and related concepts. Both researchers participated in the coding phase with a double-checking revision of the process to minimise inaccuracy.

Results

5.1 Evidence 1: The consistent academic attention to gender-based disinformation begins in 2020

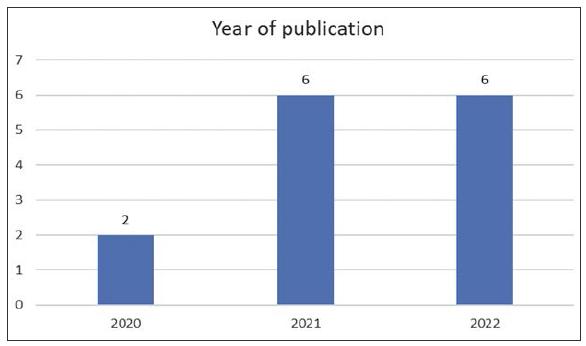

Using the method described, we obtained 14 articles that related disinformation and gender as a frame of the study and not an analytical category in the last ten years (2013-2023). Although the disinformation field of study is recognised as not being new in academic research, the attention to gender issues related to the disinformation phenomenon only begins to be addressed in 2020. The graph below (Figure 2) shows stable growth in the number of publications in 2021 (n=6) and 2022 (n=6).

5.2 Evidence 2: Quantitative and mixed research designs are prevalent

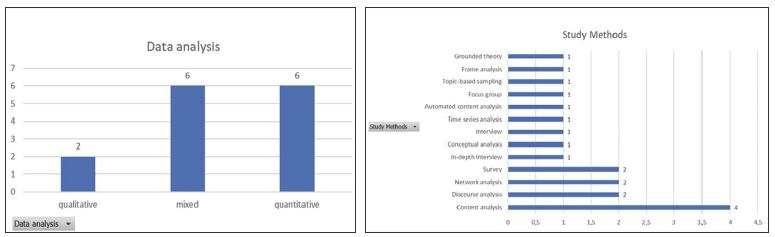

The analysed studies show a higher prevalence of quantitative and mixed approaches. While the mixed approach (n=6) provides a broader perspective than the quantitative approach (n=6) when attempting to establish a correlation between patterns and perceptions, the exclusively qualitative approach (n=2) is still relatively uncommon, featuring in only two works. Furthermore, the methods employed in the studies encompass a range of frameworks, including content analysis (n=4), survey (n=2), network analysis (n=2), and discourse analysis (n=2). Given that gender-based disinformation represents a relatively recent area of focus within the broader field of disinformation studies, we regard these selected approaches as incipient and a starting point for examining this phenomenon.

5.3 Evidence 3: The research focus remains on content descriptions of disinformation

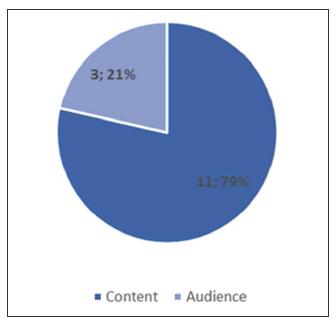

Not surprisingly, considering the preference for quantitative and mixed approaches for studying gender-based disinformation, the most prominent research focus is the content (n=11, 79%). In contrast, three papers focus on audience research, representing 21% of the corpus (see Figure 4). Notably, there is a lack of studies that engage in understanding disinformation content practices. Further research should concentrate on how disinformation content and narratives are produced, the frequency of technology usage, and, if applicable, the previous strategies and methods employed by these technologies.

5.4 Evidence 4: Twitter is the most analysed platform

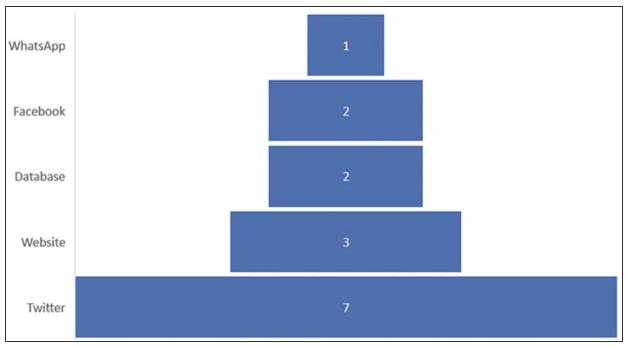

Twitter (n=7) is the most analysed platform by the studies (Figure 5). Fact-checking websites (n=3) and databases (n=2) are also privileged in a digital context. Despite the difficulties in researching WhatsApp due to limitations imposed on data collection (Ramos, Machado & Cerqueira-Santos 2022), this messaging app (n=1) is also analysed.

5.5 Evidence 5: The focus of research and institutions is centred on the countries from the “Global North”

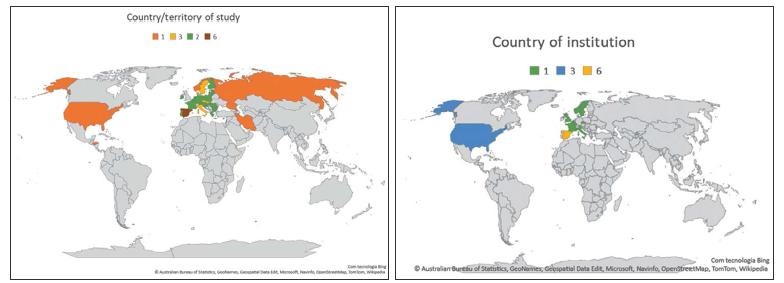

We use the concepts “Global South” and “Global North” in a political, rather than a geographical sense (McFarlane 2006). As Phiri (2021, 50) observes, the Global South has been frequently regarded as a “zone of collecting data”, a subaltern place that faces the consequences of being labelled incapable of producing knowledge. In our corpus, the Global North is a “zone of theory,” and simultaneously the region under examination. If academic imperialism persists, perpetuating asymmetrical power relations, the knowledge produced will continue to offer repetitive universal approaches and seek universal solutions to specific problems.

According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report (2022),1 only two of the top five countries listed, Norway (third place) and Sweden (fifth place), are the subject of study in the analysed articles. Iceland and Finland (first and second place, respectively) and New Zealand (fourth place) do not appear in the corpus. In contrast, Spain is the most frequently studied country (n=7), ranking eighth in the WEF report.

Italy, Sweden, Denmark, the Czech Republic, and Venezuela each have three studies in the corpus. Latin America and countries in Africa and Asia, which are part of the Global South, are neglected in the analysed papers. As demonstrated in Figure 6, both the categories of country/territory of study and country of institution concentrate knowledge production and attention on the Global North. Spain (n=6) is the most notable country, followed by the United States (n=3). In total, 13 authors are affiliated to European universities, indicating that the Global North is studying the Global North.

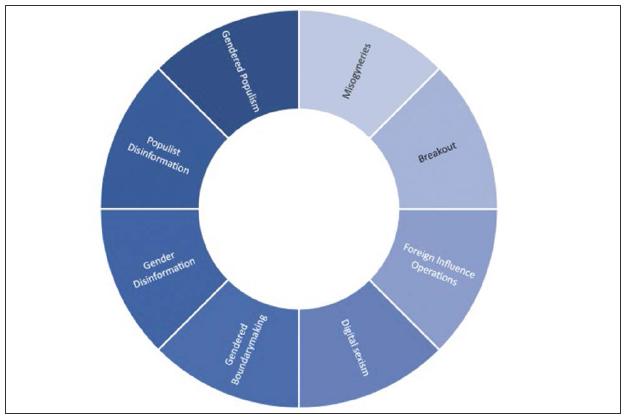

5.6 Evidence 6: The range of concepts related to gender-based disinformation is diverse

The concept of “gendered populism”, as borrowed from Sofos (2020), is discussed in Article 11[2, referring to women who criticise the new wave of populists and their promotion of traditional gender roles and misogynistic language. It emphasises that these women are often attacked, particularly on Twitter and other social media platforms. Article 3 explores the phenomenon of “populist disinformation” in Spain, identifying the “Tuitosfera” as a significant factor in shaping public opinion in the virtual realm and as the primary source of populist disinformation. Article 12 conceptualises “gendered boundary-making” as the shared narratives concerning gender and national identity. This concept aims to better understand how disinformation resonates within cultural, ethnic, and racial narratives of gender.

Article 14 introduces the term “digital sexism” and “gender disinformation” to describe the targeted hostilities experienced by women in the digital sphere. It mentions Occeñola (2018) to refer to direct attacks on women identified as “gender disinformation,” while Sobieraj (2018) labels it as “digital sexism.” These scholars highlight the extreme gender-based abuse and hostility that women face in online interactions, where all sorts of derogatory comments are prevalent.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 7 Concepts of studies based on Web of Science and Scopus databases (29 March 2023)

We have also identified other relevant concepts related to gender-based disinformation (Figure 7). Article 8 posits the term “foreign influence operations” to argue that, although women encounter disinformation and harassment differently, there is a lack of systematic studies examining the gender dimensions of how foreign state actors instrumentalise narratives about gender and women in contemporary disinformation dynamics.

We also identify the term “breakout” to describe the spread of influence operations across platforms, individuals, and information sources within the ecosystem [11]. Additionally, Article 11 introduces the term “misogyneries” as a mix of misogyny and synergies, characterising how authoritarian male leaders worldwide mutually reinforce misogynistic attitudes, leading to an environment that tolerates violence and discrimination against women. Within this context, disinformation has become a significant harm within the digital realm.

4. Discussion

The significant relevance of publication occurred in 2021 and 2022. Both years are remarkable periods due to the COVID-19 crisis and the further war in Ukraine. These contexts are the focus of seven articles. More specifically, five studies mention or are related to the pandemic [3; 4; 5; 6; 12], and two focus on Russian propaganda [8; 12]. Regarding the research focus and outcomes identified, briefly described in the appendix, the gender dimension is cross related to disinformation in various spheres. More specifically, the political arena [1; 2], the news media context [6], and the educational field [13]. The articles address three recurring themes: 1) women are the frequent target of disinformation; 2) weaponised narratives connect to dark politics; and 3) proposed solutions to address the problem still rely on media literacy programs and regulatory measures.

Firstly, women are major targets of gender-based disinformation. Using a content analysis strategy, Article 2 provides evidence that threats get worse when racialised women are the target of disinformation. Gender and race frame identifiers were used to stereotype Kamala Harris on Twitter, calling her angry, promiscuous, and a loser when she ran as U.S. vice president in 2020. As women have started occupying spaces of power and political representation, which were formerly male-dominated, systematic violence against them has been occurring to silence their voices and representation positions in the public arena. In the same vein, female journalists’ experiences with the disinformation phenomenon are also studied. A mixed-method analysis conducted by the authors of Article 4 showed that 89,6% of the journalists who responded to a questionnaire in Spain declared that they had been the target of hate speech and experienced other forms of harassment. During the in-depth interviews with sports female journalists, they cited online violence as a common practice and pointed out that the aggressors usually attack their work capabilities and insult their physical appearance. Resorting to keyword analysis, network analysis, and open-source intelligence techniques (OSINT), Article 11 shows how women journalists work in challenging authoritarian regimes, shedding light on the intensity and scale of online attacks in the Persian Gulf. Also, female journalists are purposely targeted to discredit their voices in society.

Secondly, weaponised narratives connect to dark politics. Far-right extremism and (neo)conservative movements extensively employ gender-based disinformation against specific targets. Article 3 focuses on hate and hostility messages disseminated in the digital sphere featuring the presence of interrelated groups that coordinate and provoke confrontation related to issues involving the rights of women and LGBTQIA+ people. Likewise, Article 7 shows that coordinated disinformation campaigns use anti-gender discourses. In addition, disinformation narratives that target intersectional identities and issues, such as feminism and female empowerment, operate to demobilise activists, spread anti-democratic propaganda, and create viral content around political topics [8; 9].

Following a qualitative analysis of more than seven thousand tweets, Article 8 discusses how foreign state actors engage in covert influence operations targeting feminist activists and politicians by co-opting narratives about feminism itself. According to the authors, such a strategy is used to undermine women’s ability to form the collective identity necessary for political mobilisation. Moreover, as Article 12 demonstrates, such “gendered boundary-making” shapes audiences’ interpretations in crucial ways in the Nordic context (Swedish, Danish, and Norwegian). Also importantly, digital communication centralisation involves both the coordination of production (framing or chosen narrative) and the distribution of content, which is linked to the pseudo-media that comprises this ecosystem [5; 13].

Thirdly, the proposed solutions to address the problem still rely on media literacy programs and regulatory measures. Papers commonly recommend digital media platform regulation, and media and gender literacies. We have identified proposals for education and training to address the problem of disinformation and hate speech. The authors of Article 4 believe that regulatory and technological measures involving social media companies should be implemented. Despite that, they suggest that the addition of media literacy and gender training to the educational curriculum could mitigate the problem. Moreover, Article 6 points out the importance of media literacy in preventing the dissemination of harmful content. More broadly, the authors of Article 10 advocate more gender equality to create better societies.

5. Conclusion

This study emphasizes the need to understand and address gender-based disinformation, which remains underexplored. The scoping review revealed some research gaps: there is an overrepresentation of Global North studies with a focus on disinformation content, while the Global South is neglected. Women are common disinformation targets, linked to “dark participation” (Quandt 2018). Academics suggest media literacy and regulatory measures to combat disinformation, needing further empirical research for validation. Additionally, a critical approach is essential, considering historical, contextual, and local factors, understanding their impact on marginalized groups, such as racialized women, feminists, and transgender and non-binary individuals. The current approach to disinformation lacks a feminist lens to analyse its intersection with structural inequalities and its effects on marginalized groups. Scholars argue that knowledge production historically served hegemonic power structures, perpetuating the invisibility and exclusion of women and communities of colour from society (Marwick et al. 2021).

This is especially true when we look at the limitations of this study. Regarding the methodological approach, including indexed databases and excluding papers published in journals that do not occupy the top tiers of the ranking system creates a symbolic annihilation. The PRISMA research protocol implies a favouring of academic production from elite universities in the Global North. The consequence is clear: current approaches to gender-based disinformation lack critical lenses to examine how misleading and false narratives interact with structural inequalities and their impact on marginalised groups.

We emphasise the need for future research to tackle this issue in an interdisciplinary/transdisciplinary manner. Additionally, scholars should consider employing the lens of intersectionality as an analytical framework to understand how racism and sexism function as mechanisms of oppression, exclusion, and silencing of racialised women - a topic extensively explored within the long tradition of Black feminist thought (Carneiro 2011; Gonzalez 2019 [1980]; Kilomba 2020) and perpetuated through new digital technologies. Moreover, further research should examine how digital platform companies perceive the Global South as exploitable markets and labour, prioritising financial gains with minimal responsibility (Simmons 2015).

Combating gender-based disinformation demands a comprehensive and inclusive approach, aiming to foster an informed and equitable society. Despite being a rapidly expanding and developing issue of concern, scholars might consider the need for identifying best practices for responding to the problem considering contextual, political, and historical factors, as well as users’ media behaviours and practices of daily communication.