Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Faces de Eva. Estudos sobre a Mulher

versão impressa ISSN 0874-6885

Faces de Eva. Estudos sobre a Mulher no.Extra Lisboa out. 2019

ESTUDOS

Interweaving is like knitting: Paula Rego’s ‘interior theatre’ and the intricate pattern of her emotional and intellectual networking

Entrelaçar é como fazer tricot: O ‘teatro interior’ de Paula Rego e a estrutura em rede das suas relações afectivas e intelectuais

Ana Gabriela Macedo*

* Universidade do Minho, 4704-553, Braga, Portugal, gabrielam@ilch.uminho.pt

ABSTRACT

This paper establishes a dialogue amongst visual and literary narratives, drawing on Paula Rego’s intricate series of art compositions which she has been fearlessly creating over the years in a constant “interweaving” process with fellow artists and writers, classic and contemporary, Portuguese or British. Italo Calvino’s essay on “Visibility” (Six memos for the next millenium, 1988) will provide a structural guideline to our analysis and Balzac’s tale “Le chef d’oeuvre inconnu” (1845), will be comparatively discussed as an intriguing reflection on the nature of the work of art, the search for aesthetic perfection and the irrepresentability of the sublime, through the allegory of the feminine.

Keywords: visual narrative; interweaving; femininity; gender; sublime.

RESUMO

Este texto pretende estabelecer um diálogo entre narrativas visuais e literárias, focando a obra construída ao longo dos anos por Paula Rego, plena de “entrelaçamentos” e diálogos intertextuais e interartísticos. Pretende-se evidenciar que o “teatro interior” de Paula Rego é povoado de vozes, discursos e narrativas polifónicas desfiando fronteiras disciplinares e permanentemente questionando representações estereotipadas de género. O ensaio de Italo Calvino sobre a “Visibilidade” (Seis propostas para o próximo milénio, 1990) será um leitmotif desta análise comparativa, assim como o conto de Honoré de Balzac “Le chef d’oeuvre inconnu” (1845).

Palavras-chave: narrativa visual; entrelaçamento; feminino; género; sublime.

‘This is how I always work - drawing on my own life and dreams and feel-

ings [...]. Interweaving is like knitting’ (Rego apud McEwen, 1997 [1992]).

‘[…] the only thing I knew was that there was a visual image at the source of

all my stories’ (Calvino, 1996 [1988]).

‘You are looking for a picture, and you see a woman before you.’

(Balzac, 2016 [1845]).

As I’ve mentioned before, one of the features of Paula Rego’s work that most fascinates me is its deliberate exposure of networks, cross-references and, in her own words, ‘interweavings’([1]). With some distance now, I understand

that my passion for this trace in Rego’s art is also a reflection of my own personality and trajectory, as largely our critical endeavours and our biographies are, if not mirror images, impossible to tell apart from each other. Thus, on a personal note, I dare to follow some of my own interweavings in this paper, as I pursue Paula’s. At the same time we will be, surely not checking, but allowing ourselves to be seduced by the labyrinth of Rego’s ‘interior theatre’ and following the summon of its multiple innuendos and challenges. Nevertheless, it is not solace that we can expect to meet at the end of the tunnel, but an overall intranquility substantiated in her ‘power of vision’, which is inextricable from her critical and political commitment and an aesthetics of feminine empowerment.

I

To start at the beginning … In the late nineties, the tip of the thread that first led me to Paula Rego([2]) was my fascination with Angela Carter’s storytelling wonders, her wild imaginary, her prodigious language and her open commitment to a gendered aesthetics. The first essay I wrote on Rego’s work (her illustrations of The nursery rhymes [1989]) links the poetics, visual and literary, of both artists (Macedo, 1999, pp. 245-254). Not long after that I found the third key element in this gynesis and network of women artists, Marina Warner, writer, critic and mediaevalist scholar - the three artists similarly engaged in the “demythologising business” proclaimed by Carter.([3]) Warner wrote the Introduction to Carter’s second volume of Fairy tales, published after her untimely death in 1992, claiming that it was as ‘a tribute to her potency that while she was alive people felt discomfited by her, that her wit and witchiness and subversiveness made her hard to handle’ (1993, p. xvi). In 1994 coincidentally Warner wrote the Introduction to Rego’s Nursery rhymes, marking the onset of a long professional collaboration and an affectionate complicity between both artists (eg. the Introduction to Rego’s Jane Eyre in 2003, numberless articles on Rego’s work).

In the process of the research I have been developing on Rego’s work and its ‘interweaving’ with other art forms, namely the pervasive link with literature, I believe it is yet to be designed the full mapping of her affinities, both aesthetic and emotional, with the Portuguese artists, painters and writers, and largely with the Portuguese culture and history which she so adamantly inscribes in her art.([4])

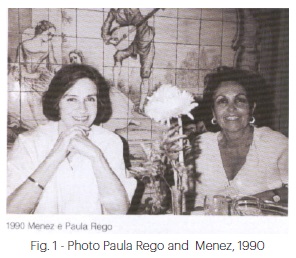

In a previous essay I focused on the role of two artists with close ties with Rego, the painter Menez (Maria Inês Ribeiro da Fonseca) and the poet Alberto de Lacerda([5]). Both were crucial figures around whom one can feel the centripetal force that firmly pulls Rego to her culture of origin, her blood roots, her emotional geography. Very briefly I want to evoke those two artists as, despite their grandeur, both have become rather spectral and underrated figures in the Portuguese cultural constellation([6]).

I’ll start with an anecdote. In one of my early interviews with Paula Rego, later on published in my book (Macedo, 2010), when I asked her to name the artists whose work she felt closer to, she promptly answered: the Portuguese ceramist Bordalo Pinheiro, the Belgian painter James Ensor, Goya and all the XVIII century caricaturists. ‘What about women artists?’ I asked her. And she replied: ‘Suzanne Valadon, Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morrissot, and amongst the Portuguese, Menez, whom I was very fond of and whose work I admired immensely. I used to spend a lot of time with her whenever I went to Lisbon, and when I would come back to London I brought it all with me and copied it. Only we are very different. She used to tell me: “You come here, you see my work, then you go back to London and you make it much better”’ (Macedo, 2010, p. 49).

In 1990 she was awarded the Prémio Pessoa in recognition for her ‘enlightened’ work, as signaled by Hélder Macedo (1998, p. 10). Poets such as Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, Salette Tavares, António Ramos Rosa, Hélder Macedo, João Miguel Fernandes Jorge, among others wrote inspired essays on her work([7]). From 1965-69 she lived in London and became part of the group of artists and expats amongst whom were Alberto de Lacerda, Paula Rego, Vic Willing, Mário Césariny, Hélder Macedo and João Vieira.

Lacerda, who had been introduced to Paula Rego by Menez, on his turn introduced the couple Rego-Willing to John McEwen, the critic who would become a figure of paramount importance in the promotion of Rego’s career both in the UK and in Portugal([8]). The Mozambican born poet who had adopted London as his new ‘homeland’ since 1951 (Portugal then submerged in Salazar’s dictatorship), lived in a close circle of writers, artists and intellectuals, and he had played a central role in Paula’s career since her first exhibition at the Gulbenkian Foundation (1961). After her first solo exhibition at the National Society of Fine Arts [SNBA] in Lisbon (1965), Lacerda famously interviewed Paula for the Diário de Notícias, calling the young artist, then 29 years old, ‘an exceptional artist whose desperate vision came to enrich our collective imagination’ (1965, p. 3). The text of this interview has one of the most ever quoted lines of Rego: when Lacerda asks her the standard question ‘Why do you paint?’ Paula answers, ‘I’ve been asked that before and my answer was: “To give fear a face”, but also because I cannot help painting’ (1965, p. 4).

A lot could be said about this crucial interweaving in Paula’s career and the meanders of the London-Lisbon connection in this generation of expatriate artists and writers, having the poet Alberto de Lacerda as their friendly mentor and one could say, their impresario (in the sense Pound uses the term to describe his own role among modernist poets in England)([9]), but that is not the objective of this essay. To finalize my excursion into this network of affection and positive contamination, an intricate pattern of lives and cultures ‘in transit’, constituted by expats and émigrés in London, (the city the poet called ‘Paradise of human dignity’([10])) I will quote from Lacerda’s vivid description of Paula in his essay ‘Paula Rego and London’:

To talk about Paula Rego is, amongst other difficult things, to talk about a number of contradictions; mysteriously unified contradictions. This woman - eternally young, eternally beautiful - maybe more beautiful today than twenty five years ago when I met her - found herself, found her hub as a child, and since then never left it. [...] Paula is always at ease, always free - nothing, never, no one has ever chained her - even when she seems shy or embarrassed. ‘Oh Alberto! What a shame to exhibit these things’ [...]. She was to me, since the very moment I knew the work and the creature - a paragon of freedom, ‘free freedom’ as the Other would have said it; and this happened in the horrendous years of the dictatorship that some - even those! - are now suggesting neither were they that terrible, nor was there ever a dictatorship (1989, p. 18)([11]).

II

1. Moving on to other aspects of Rego’s interwoven poetics, I want now to follow another thread and focus on the nature of the images in her work, their ‘narrativity’, vis a vis the ‘visibility’ of narratives themselves, as proposed by the Cuban born Italian writer Italo Calvino.

In the fourth of his lectures from Six memos for the next millenium (1996), to be read in Harvard within the prestigious Charles Eliot Norton Poetry Lectures (1985-1986)([12]), Calvino chose ‘Visibility’ as one of the ‘values, qualities or peculiarities of literature’ which he held ‘closer to his heart’ and which granted him ‘confidence in the future of literature’ in the wake of the new millennium, a time when, he claimed, ‘we frequently wonder what will happen to literature and books in the so-called postindustrial era of technology’ (1996, p. 1). The writer significantly adds that he will try to situate these Six memos ‘within the perspective of the new millennium’.

In the course of his lecture on ‘Visibility’, Calvino claims: ‘When I began to write fantastic stories, I did not yet consider theoretical questions; the only thing I knew was that there was a visual image at the source of all my stories’ (1996, p. 88 [my emphasis]).

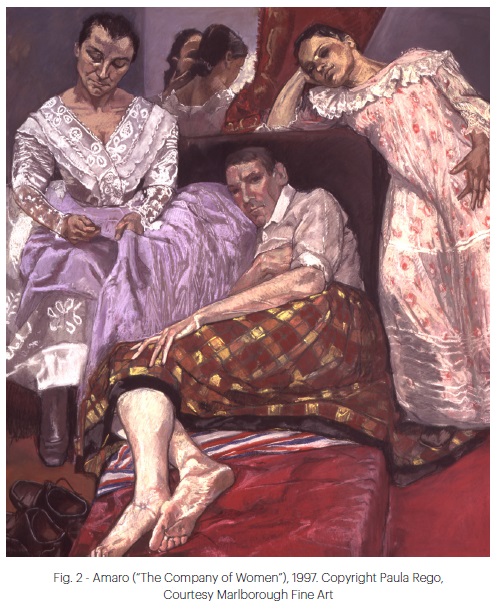

I propose that we revert this statement, which concerns the narrative and textual image, and say it in the context of Rego’s pictorial oeuvre. And I quote the artist when commenting on ‘The ambassador of Jesus’, one of her Father Amaro’s pastels (1997): ‘The images in this picture go together.

They engage with each other, lock with each other in a visual drama. I put things in instinctively. The novel is only a starting point, a trigger, then the images take over, like a box of secrets, like Russian dolls’.

And she further adds commenting on the composition ‘Mother’, from the same series: ‘Visual things, formal elements, create what I call a story’([13]). Rego’s painting lives through stories, is fed by stories which she reads in between the lines, turns upside down, dis-figures and re-figures, enhancing their estrangement, transgressing their limits, exposing their inner tensions, staging the gestures and emotions of their protagonists, while immersing herself wholly in this performative process, close to children’s play, a kind of hide-and-seek some have called unheimlich.([14])

‘The stories go with the picture... I mean the stories make the picture. You do it with images. To know what images to put in there, you have some sort of story’([15]), she says regarding her composition Celestina’s house (2000-01) which celebrates the carnivalesque ambivalence of a popular female image, a ‘courtesan’ of her own kind, who is ‘more than just a tart’, she says, ‘a woman that restores broken hymens’, a ‘subversive character’ (Rego, 2001, p. 13).

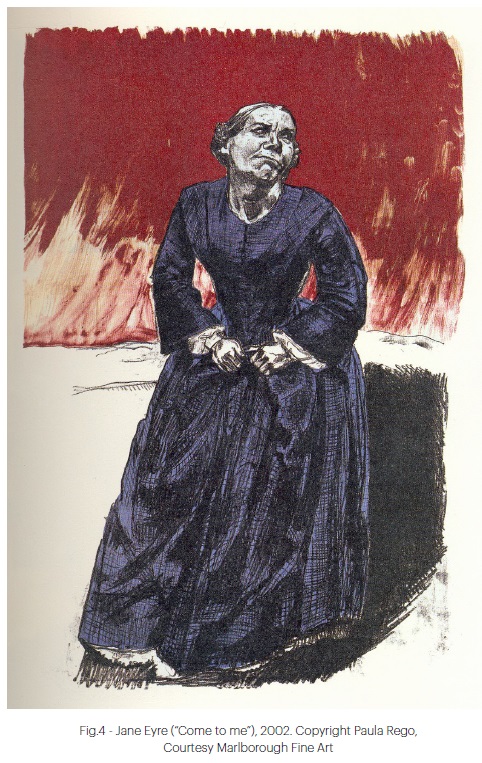

Towards her composition Rego claims to be inspired by two Renaissance Iberian authors, Fernando de Rojas and the Portuguese Gil Vicente. A similar case is the Wide sargasso sea (2000), inspired by Jean Rhys’s 1966 novel (Rhys, 1993 [1966]). Both compositions are palimpsestic retellings of women’s lives intertwined with personal and collective memories. Rhys’s novel, as well known, is itself a re-reading of Jane Eyre, Brontë’s Victorian Bildungsroman, which Rego revisited in an important series of prints and pastels in 2001-2. Both works, Rego’s images and Brontë’s narrative, would later combine in the making of a version composed for the stage by the playwright and director Polly Teale - towards the making of the play After Mrs Rochester (2003). More recently, in 2015, images and text were again revisited and restaged by director Sally Cookson in a new version of Jane Eyre([16]).

A complex network of contaminations, one would say, which has Rego and Brontë as godmothers, visual and textual imagery densely intertwined. As argued by the artist in the previously cited interview apropos ‘Celestina’s house’, the images and the figures succeed each other as they take shape on paper, and they ‘not only make a whole scene by their movement, they also bring their own stories’, for ‘a composition is a visual equivalent to emotions’, she claims (Rego, 2001, p. 10).

The fact that Rego is a “visual storyteller”, incessantly engaged in her pleasurable ‘rumination of narratives’ of a wide spectrum, from her early Nursery rhymes (1994) to the recent Stone soup (2014), her re-visions of Brontë, Dickens, Rhys, Martin McDonagh as well as Alexandre Herculano, Camilo Castelo Branco, Eça de Queirós, the traditional tales of Consigleri Pedroso, Perrault, Grimm, Andersen, alongside newspaper cuts, Walt Disney movies and the satirical imaginary of the ceramist Bordalo Pinheiro proves that her palette is voracious and that she takes to the heart the ‘art of the storyteller’([17]).

Walter Benjamin famously identified storytelling as a storehouse of memory, the art of preserving a treasure that seemed ‘inalienable to us, the securest among our possessions, […] the ability to exchange experiences’ (1979, p. 83). Benjamin describes the oral tradition of storytelling as a ‘slow piling one on top of the other of thin, transparent layers’, since the perfect narrative, he says, is composed of a ‘variety of retellings’ (1979, p. 93).

Paula Rego belongs to this mythical category of storyteller, excelling in the construction and deconstruction of narratives, permanently de-framing and re-framing the many layers of her visual stories, interweaving History, the past rendered present, the theme of domination, the sacred and the profane, through a disquieting vision issued from her ‘interior theatre’. As she confided to her critic and friend John McEwen: ‘Painting is practical but it’s magical as well. Being in this studio is like being inside my own theatre’ (McEwen, 1988, p. 48 [my emphasis]).

Undeniably, Rego’s visual stories create an imagery that is ‘complex and often, very personal’, as Vic Willing, her late husband contends (1971,p. 43). The painter Vic Willing, at the same time her most astute and lyrical critic (as Ruth Rosengarten reminds us) (1988, p. 18), in a poignant essay titled ‘Inevitable prohibitions’([18]), emphasizes Paula’s early “immersion” in stories since childhood. Willing makes a strong remark worth considering in this context:

‘Regarding humour, she disappointed some admirers who wanted more, when she decided that some things are not a laughing matter. Wit handles serious matters with a light touch (…) even so, to insist always on finding reasons to laugh would betray embarrassment about life’s dark side. She has none’ (1988, p. 7).

It is worthwhile taking this comment into consideration when one looks back into her systematic confrontation of authority, censorship, humiliation, secrecy, human and female exploitation, in particular. Since her early collages from the 60s, blaring satires in reds and yellows of Salazar’s dictatorship [‘Salazar vomita a pátria’ (1960), ‘Os cães de Barcelona’ (1961)]; her innumerous series and compositions where abomination and revulsion are central issues [i.e., ‘First mass in Brazil’ (1993), the ‘Untitled’ pastels on clandestine abortion (1998-9), the ‘Interrogator’s garden’ (2000), ‘War’ (2000), ‘Life of Mary’ (2002), ‘Human cargo’ (2007), ‘Female genital mutilation’ (2008), to name just a few], Rego has not ceased from, to paraphrase Vic Willing, ‘snatching chestnuts from the fire’ and ‘defying the pain’ (1988,p. 8). At the same time that she delicately intertwines present and past memories, stories and History, ‘keeping the pattern, as though she was knitting’ (McEwen, 1997, p. 127). And in all this, ‘she manages to be convulsive and fluent, dream-like and ferocious’, as corroborated by Alberto de Lacerda (apud McEwen, 1997, p. 83).

2. But let us return to Calvino. In a further section of his essay on ‘Visibility’, the writer claims:

If I have included visibility in my list of values to be saved, it is to give warning of the danger we run in losing a basic human faculty: the power of bringing visions into focus with our eyes shut, of bringing forth forms and colors from the lines of black letters on a white page, and in fact of thinking in terms of images’ (Calvino, 1996, p. 92. [Emphasis in the original]).

‘Thinking in terms of images’. Bearing this claim in mind, I want now to call attention to the visionary quality of Rego’s work. A faculty she has been consistently exercising in her work. During her artistic residence at the National Gallery in 1990, endowed with the prestigious responsibility of creating new compositions which ‘reflected’ upon the classical works of the Gallery’s collection, she described this tremendous task of appropriation, assimilation and re-vision, in the following terms, akin to a postmodern Alice:

I was very scared and a bit daunted! But to find one’s way anywhere one has to find one’s own door, just like Alice, you see. You take too much of one thing and you get too big, then you take too much of another and you get too small. You’ve got to find your own doorway into things (...) and I thought the only way you can get into things is, so to speak, through the basement (...) which is exactly where my studio is, in the basement! So I can creep upstairs and snatch at things, and bring them down with me to the basement, where I can munch away at them. (...) I’m a sort of poacher here, really, that’s what I am. (Wiggins, 1991, p. 21 [my emphasis]).

And this poaching, munching and ruminating gave the light to Crivelli’s garden (1990-91), the magnificent triptych that is now in the walls of the Sainsbury aisle of the National Gallery (painted after Carlo Crivelli’s Madonna della Rondine). ‘It’s a picture all about stories, but also about how stories and learning are passed from generation to generation’ (Rego apud McEwen, 1997, p. 268), she says. But also the white and blue cobalt Renaissance garden, reminiscent of the artist’s own childhood garden at Ericeira and the traditional Portuguese tiles, is entirely peopled by women saints for, she claims: ‘I preferred to paint women; and it was also a homage to them, their steadfastness and courage - the way they never gave up Faith despite being put to the rack or whatever’ (Ibid. p. 255).

Years later, when Rego is engaged in her re-visitation of Jane Eyre it is the visionary young woman and her ‘power of vision’ that most fascinates her.

It is her restlessness, her independence of mind and her anger that trigger the exhilarating images she creates. In Rego’s images unmistakably resonate Jane Eyre’s words:

‘Anybody may blame me who likes, (…) - that then I longed for a power of vision which might overpass that limit; (…) Who blames me? Many, no doubt; and I shall be called discontented. I could not help it; the restlessness was in my nature’ (Brontë, 1984 [1847], pp. 140-1).

The visionary power of Rego’s work, her ‘thinking in images’, is thus center stage in her work, as is her vindication of a re-vision of History and her ‘sabotage’([19]) of tradition, past and present interwoven, based on women’s agency, through rupture, insurrection and excess. As she openly claims:

My pictures are pictures that are done by a woman artist. The stories I tell are the stories that women tell. If art becomes genderless, what is it? - a neuter? That’s no good, is it? No, you’ve got to have everything at your disposal to be in touch with everything; that includes sex as well. You’ve got to have a woman’s sex, you know; it’s quite different from the men. My responses towards working from the model would be different from that of a man working from the model. It’s an advantage, you know, because there are stories to be told that are never told. It has to do with such deep things that haven’t been touched on - women’s experience (Roberts, 1997, p. 85).

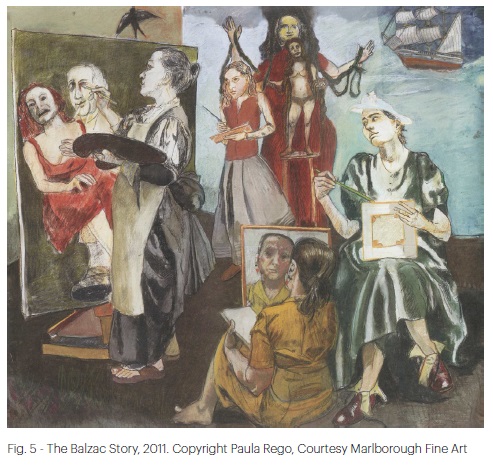

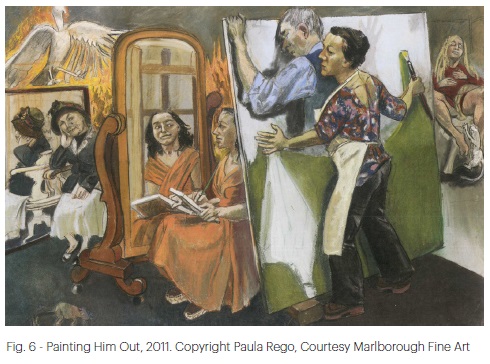

3. In the final section of his essay, Calvino asks us (and himself) the following question: ‘Will the literature of the fantastic be possible in the twentyfirst century, with the growing inflation of prefabricated images?’ (1996, p. 95). This leads him to reflect upon Balzac’s fantastic tale/ philosophic essay ‘Le chef d’oeuvre inconnu’ (1831-37) (“The unknown masterpiece”), which has been commented upon as a parable of modern art, but which can also be read, he argues, as a ‘parable of literature’ - ‘about the unbridgeable gulf between linguistic expression and sense experience, and the elusiveness of the visual imagination’ (Calvino, 1996, pp. 96-97). Balzac’s tale also leads us to our final section as it inspired two of Rego’s recent compositions, titled ‘The Balzac story’ (2011) and ‘Painting him out’ (2011).

Likewise Calvino, we ask ourselves when faced with Rego’s pictorial version of Balzac’s tale, her transgressive appropriation of a classical ‘chef d’oeuvre’, her parodic inversion of the gender roles between male artist as creator and female as ‘inspiration muse’, or simply object of the male gaze, even if apparently sanctified, but surely disembodied and disempowered. Is such a subversion of this ‘tableau’, such a clear mise-en-abîme of the traditional ‘male artist-female model’ frame, the ‘unframing’ and exposure before the viewers’ eyes of its limits and coercions - aesthetic, ideological, social, sexual - , is such a transgressive gesture plausible and consistent in this day and age, as a utopian/visionary artistic practice? And what is its impact? Those are some of the questions we are faced with when pausing to reflect upon this apparently innocuous compositions Rego ironically chose to name ‘Balzac’s stories’([20]). And it is worthwhile reminding oneself that these are recent compositions created when the artist was close to her eighties. ‘Snatching chestnuts from the fire’, as Vic Willing would put it.

As Calvino writes in his essay, ‘the layers of words that accumulate on the page, like the layers of colors on the canvas, are yet another world, also infinite but more easily controlled, less refractory to formulation’ (1996, p. 97). Balzac names that space of creativity without borders the ‘undefinable’, which Calvino appropriates as a perfect definition of the fantastic genre, as ‘everything that eludes the limited perceptions of our spirit’ (Ibid.) and renames the ‘undecidable’ in art, a refusal of aesthetic reification, be it ‘verbal matter’ or ‘polymorphic vision’. He writes: ‘The artist’s imagination is a world of potentialities that no work will succeed in realizing’, it is thus in the ‘ambiguity’ of Balzac’s tale that ‘its deepest truth resides’, Calvino claims (Ibid.). The tale is a kind of postmodern essay avant-la-lettre, which has inspired innumerous philosophical reflections, rewritings and adaptations. Calvino’s dialogue with it within the fourth of his Memos for the next millenium, assigned to ‘Visibility’, is in praise of the ‘polymorphic visions of the eyes and the spirit (…) representing the many-colored spectacle of the world on a surface that is always the same and always different, like dunes shifted by the desert wind’ (1996, p. 99). Balzac’s tale is at one time a pictorial allegory of the aesthetic sublime and of the ‘eternal feminine’, as well as a claim on the visionary power of the artist that remains opaque to his contemporaries, less able with the ‘power of vision’, or with the ‘infinity of the imagination’, in Calvino’s words.

‘Aha!’ he cried, ‘you did not expect to see such perfection! You are looking for a picture, and you see a woman before you. There is such depth in that canvas, the atmosphere is so true that you cannot distinguish it from the air that surrounds us’. Exclaims Frenhofer, the elderly painter, before his astonished young colleagues Porbus and Nicolas Poussin, when he unveils his ‘masterpiece’ to them: ‘It is the form of a living girl that you see before you. Have I not caught the very hues of life, the spirit of the living line that defines the figure?’, says the elderly artist. And he unveils a formless canvas covered in ‘confused masses of color and a multitude of fantastical lines’, where at long last they distinguish a visible image: ‘In a corner of the canvas, as they came nearer, they distinguished a bare foot emerging from the chaos of color, half-tints and vague shadows that made up a dim, formless fog’. ““There is a woman beneath”, exclaimed Porbus. ““He is even more of a poet than a painter,” Poussin answered. ‘What joys lie there on this piece of canvas!’ exclaimed Porbus (Balzac, 2016 [1845])([21]).

Paula Rego, drawing on Balzac’s tale, its polymorphous symbology and its questioning of the irrepresentability of the aesthetic sublime creates her own version of ‘Balzac’s story’, inverting/subverting the traditional roles of male artist/female object of representation, empowering the agency of the woman artist in her defiant manner. Through Rego’s palette the act of creation is symbolically transfigured, staged ‘inside out’, invested with a new power: that of the female artist - at one time disquieting, ironical and fearless. Rego’s two pastels, ‘Painting him out’ (2011) and ‘The Balzac story’ (2011) give us her ‘reading’ of Balzac’s tale; both ‘narratives’ not that dissimilar in the end, but visionary, utopian and radical each in their own way. Moreover, as often is the case in Rego’s work, there is a palimpsestic intratextual dialogue between these compositions and some of her earlier works, thus restaging or recasting them anew - namely two powerful composition created in 1990 during her residency at the National Gallery, ‘The artist in her studio’ and ‘Joseph’s dream’. Similarly to ‘Balzac’s stories’ both compositions are transgressive re-visions of Art History and visionary creations of female empowerment.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

My conclusion is suspended, a lot remains unsaid. I will end my text with the artist’s own words, always surprising, always bewildering, and a few impromptu photographs from her Camden town studio, the material location of her ‘interior theatre’, as she often called it: ‘Painting is practical, but it’s magical as well. Being in this studio is like being inside my own theatre’ (McEwen, 1988, p. 48).

In the occasion of her 80th anniversary, in one of her interviews, Rego wittily claimed: ‘I’m not 25 anymore, or even 50, more’s the pity. Working makes me feel better. When I’m drawing, I forget I’m tired or in pain. (…) It is not true that fear is my muse - but I do feel fear: I’m not brave in real life but I’m not frightened of doing anything in my work’ (Kellaway, 2015). It is almost uncanny to hear the reverberations of this claim in a text written fifty years earlier by Alberto de Lacerda, Poema-manifesto [Poem-manifesto], printed for Rego’s SNBA exhibition in 1965:

A tua revolta deita-se na cama, não para desistir. Mas para amar. Depois levanta-se. E és um canto - erecto, decidido, áspero. E com uma ternura misteriosíssima.([22]) [Your rebellion lies down, on the bed. Not to relinquish. But to love. And then it rises. And you are a song - erect, determined, harsh. And you possess the most mysterious tenderness.]

Finally, and intentionally so, I wish us to remain with Vic Willing’s premonitory words on Paula Rego, from his last text earlier on quoted “Inevitable prohibitions”: ‘A lifetime of courting disaster turned around at the last moment - snatching chestnuts from the fire - produces a note of hilarious triumph. It defies the pain.’ (1988, p. 8).

REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

AA.VV (1987). Alberto de Lacerda: O mundo de um poeta. Lisbon: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian/Centro de Arte Moderna. [ Links ]

AA.VV (2009). Colecção Alberto de Lacerda: Um olhar. Lisbon: Assírio & Alvim. [ Links ]

Balzac, H. (2016 [1845]). The Project Gutenberg. EBook of The unknown masterpiece. In Widger, D. (Prod.), EBook #23060. [Release Date: 17.10.2007. Last Updated: 23.11.2016].

Benjamin, W. (1979 [1970]). The storyteller. In H. Arendt (Ed.), Illuminations (pp. 83-109). Glasgow: Fontana/Collins. [ Links ]

Brontë, C. (1984 [1847]). Jane Eyre. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Carter, A. (1983). Notes from the frontline. In M. Wandor (Ed.), On gender and writing (pp. 69-77). London: Pandora. [ Links ]

Calvino, I. (1996 [1988]). Six memos for the next millennium. London: Vintage.

Dias, A. P. (1990). Os lugares (in)comuns de Menez. Jornal de letras, 18 December, pp.24-25. [ Links ]

Kellaway, K. (2015). Paula Rego, 80: ‘Painting is not a career. It’s an inspiration’ (Seven ages of an artist). The guardian, 15 November 2015. [Paula Rego interviewed by Kate Kellaway]. [ Links ]

Lacerda, A. (1965). Paula Rego nas Belas Artes. Diário de notícias, 25 December, pp. 3-4. [ Links ]

Lacerda, A. (1984). Oferenda I. Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda. [ Links ]

Lacerda, A. (1989). Paula Rego e Londres. Colóquio artes, December, pp. 18-23.

Lisboa, M. M. (2003). Paula Rego’s map of memory: National and sexual politics. England: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Macedo, A. G. (1999). From the interior: Storytelling, myth and representation: The work of Paula Rego and Angela Carter. In Literatura e pluralidade cultural: Actas 3.º congresso da APLC (pp. 245-254). Lisboa: Colibri. [ Links ]

Macedo, A. G. (2008). Paula Rego’s sabotage of tradition: ‘Visions’ of femininity. Luso-Brazilian review, 45(1), pp. 163-181.

Macedo, A. G. (2010). Paula Rego e o poder da visão: ‘A minha pintura é como uma história interior’. Lisboa: Cotovia. [ Links ]

Macedo, A. G. (2015). Performative identities and interwoven art practices: Paula Rego, Menez and Alberto de Lacerda. In R. Bueno, M. Pacheco, & S. Ramos Pinto (Eds.), How peripheral is the periphery? Translating Portugal back and forth (pp. 297315). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. [ Links ]

Macedo, H. (1998). Menez ou das presenças ausentes. In Menez: Exhibition catalogue, Galeria 111 (p. 10). Lisbon: Quetzal Editores. [ Links ]

McEwen, J. (1981). Letter from London. Colóquio artes 50 (September), pp. 58-59.

McEwen, J. (1988). Paula Rego in conversation with John McEwen. In Paula Rego, exhibition catalogue, 15 Out. - 20 Nov. (pp. 41-48). London: Serpentine Gallery. [ Links ]

McEwen, J. (1997 [1992]). Paula Rego. London: Phaidon.

McEwen, J. (2008). Retrato do poeta. Jornal de letras, 2 January, pp. 14-16. [ Links ]

Rego, P. (1994 [1989]). Nursery rhymes. London: Thames and Hudson.

Rego, P. (1998). Paula Rego: Father Amaro. London: Dulwich Picture Gallery. [O crime do Padre Amaro. Lisbon: Centro de Arte Moderna Azeredo Perdigão / F.C. Gulbenkian]. [ Links ]

Rego, P. (2001). Celestina’s house. Kendal: Abbot Hall Art Gallery. [ Links ]

Rego, P. (2012). Balzac and other stories. London: Marlborough Fine Arts. [ Links ]

Rhys, J. (1993 [1966]). Wide sargasso sea. London: Penguin Books.

Roberts, M. (1997). Eight British artists - Cross generational talk. In Lloyd F. (Ed.), From the interior: Female perspectives on figuration (pp. 77-89). London: Kingston UP. [ Links ]

Roberts, M. (1997). Paula Rego in interview with Melanie Roberts. In Lloyd F. (Ed.), From the interior: Female perspectives on figuration (p. 85). London: Kingston UP. [ Links ]

Rosengarten, R. (1988). La règle du jeu. In Paula Rego, exhibition catalogue, pp. 17-23). London: Serpentine Gallery. [ Links ]

Rosengarten, R. (2004). Alberto de Lacerda: Poema (em prosa) intitulado ‘Paula Rego’. In R. Rosengarten (Ed.), Compreender Paula Rego: 25 Perspectivas (p. 8). Porto: Fundação de Serralves. [ Links ]

Rosengarten, R. (2010). Love and authority in the work of Paula Rego: Narrating the family romance. Manchester: Manchester UP. [ Links ]

Warner, M. (1993). Introduction. In Carter, A. (Ed.), The second virago book of fairy tales (pp. ix-xvi). London: Virago. [ Links ]

Warner, M. (1994). Mother goose and Paula Rego (Introduction). In P. Rego, Paula Rego Nursery rhymes (pp. 7-10). London: Thames and Hudson. [ Links ]

Wiggins, C. (1991). Tales from the National Gallery. London: National Gallery. [ Links ]

Willing, V. (1971). The imagiconography of Paula Rego. Colóquio artes 2nd series (April), pp. 43-48.

Willing, V. (1988). Inevitable prohibitions. In Paula Rego, exhibition catalogue (pp. 7-8). London: Serpentine Gallery. [ Links ]

[1] See Macedo (2010).

[2] As always I am deeply indebted to the artist Paula Rego for giving me permission to reproduce in my work her paintings and drawings and to Marlborough Fine Arts Gallery, London.

[3] “I’m in the demythologising business. I’m interested in myths (...) just because they are extraordinary lies designed to make people unfree” (Carter, 1983, p. 71).

[4] See in this context two pioneering critical works: Maria Manuel Lisboa’s, Paula Rego: Map of memory: National and sexual politics (2003), which main objective is, as claimed by the author, the understanding of ‘the complex political and ideological palette into which she [Rego], has been dipping her brush for over forty years’ (Lisboa, 2003, p. 6) and Ruth Rosengarten’s Love and authority in the work of Paula Rego: Narrating the family romance (2010), a critical appraisal of Rego’s aesthetics in a dialogue with its Portuguese political and colonial History.

[5] See Macedo (2015).

[6] Menez’s exhibition in 2006 at Centro de Arte Manuel de Brito, Algés, was the first retrospective of her work after the 1994 exhibition at Galeria 111, in Lisbon and the Calouste Gulbenkian retrospective in 1990.

[7] Vide in this context one of Menez’s rare interviews, ‘Os lugares (in)comuns de Menez’, by Ana Paula Dias (Dias, 1990). Also a special issue of Colóquio artes, 50 (September 1981), presents an important dossier on Menez.

[8] John McEwen became indeed a pivotal figure in the making of this Portuguese-British network of artists and cultures ‘in transit’. In 1981, after Rego’s first solo exhibition in London at the Arts Council sponsored by the AIR Gallery he publishes in Colóquio artes an important ‘Letter from London’ praising Rego ‘as a star of the English, as well as the Portuguese and international, art scene’ (McEwen, 1981, pp. 58-59). In 1992 he publishes with Phaidon a monograph of Rego’s work with interviews and detailed biographical data of the artist which remains to this date a major scholarly contribution to the study and contextualization of her work (Ewan, 1997 [1992]).

[9] Lacerda’s extraordinary archive, composed of prints, photos, paintings, texts, letters and other priceless memorabilia offered by the artists who were his close circle of friends was the object of two major exhibitions: the earlier one (‘Alberto de Lacerda: O mundo de um poeta’), at Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, (AAVV, 1987), the second one at Fundação Mário Soares, Lisbon, 2009 (‘Colecção Alberto de Lacerda: Um olhar’) (AAVV, 2009). Recently, from October 2017 to April 2018, the Biblioteca Nacional Portuguesa, in Lisbon, organized a new display of the archive, which has been entitled ’Oh, vida, sê bela! Alberto de Lacerda (1928-2007)’. Shortly after the poet’s death John McEwen wrote an inspired obituary of the poet (‘Retrato do poeta’) for Jornal de letras (McEwan, 2008). Luís Amorim de Sousa, as holder of Lacerda’s legacy, has given himself the major task of preserving and organizing the archive.

[10] ‘Esta terra/Paraíso da humana dignidade/É a ditosa pátria minha amada/Enquanto a outra/Disser à luz ao amor à liberdade/Que não’(‘Londres reencontrada’ - 1963’ in Lacerda, 1984, p. 413). [‘This land/Paradise of human dignity/ Will be my beloved homeland/ While the other/ Denies light love liberty’]. My translation. Lacerda’s Obra poética was published in five volumes by the Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda: Oferenda, vols. I and II, Átrio, Horizonte, Elegias de Londres.

[11] My translation.

[12] In this celebrated volume Calvino enumerated the following five ‘values’ of literature: Lightness, Quickness, Exactitude, Visibility, Multiplicity. His sixth ‘Memo’ remained unfinished due to his untimely death.

[13] Rego’s comments on her compositions from the catalogue of the exhibition Father Amaro / O crime do Padre Amaro (Rego, 1998), unnumbered.

[14] Marina Warner in her Introduction to Rego’s illustrations of the Nursery rhymes (1994) associates the artist’s technique with the Freudian notion of the uncanny, the unheimlich, and she sustains in a reference to Rego’s disquieting imagery in this series, despite its title: ‘To be uncanny - unheimlich - there has to be an idea of home - heimlich - in the first place - but a home that’s become odd, prickly with desire, and echoing with someone’s laughter’ (1994, p. 7).

[15] Paula Rego interviewed by Edward King, February 2001, in the catalogue of the exhibition Celestina’s house (Rego, 2001, pp. 8-13).

[16] This new stage adaptation of Jane Eyre was first performed at the Old Bristol and later in the same year (2015) at the National Theatre in London.

[17] Vide The pillowman, a play by Martin McDonagh (2003) which inspired a visual composition by Paula Rego, a tryptich under the same title (2004). I analyse this visual and performative dialogue in ‘A “arte do contador de histórias” e o “dever do contador de histórias”, a chapter of my book, Paula Rego e o poder da visão (2010), pp. 130-144.

[18] Willing dies that same year, 1988.

[19] For a wider discussion of this topic see my essay ‘Paula Rego’s sabotage of tradition:“Visions” of femininity’ (Macedo, 2008).

[20] Paula Rego´s exhibition Balzac and other stories took place at Marlborough Fine Art, 29 May-30 June (Rego, 2012).

[21] All quotes from Balzac’s essay are from the previously referred to Project Gutenberg EBook of The unknown masterpiece (1845). (Chapter IICatherine Lescault), unnumbered.

[22] The uncensored version of this ‘Poema-manifesto’ is printed in Ruth Rosengarten’s Compreender Paula Rego: 25 perspectivas (2004, p. 8) [My translation].