(…) those who speak ill of women do more harm to themselves than they do to the women they actually slander. (Pizan, 2005, p. 7)

To three Ladies from French Studies: Professors Cristina Almeida Ribeiro (FLUL), Ana Paiva Morais (NOVA FCSH) and Filomena Fontes (NOVA FCSH)

As is well known, the story of Western feminism is usually divided into three ‘waves’, the first of which dates from the late 18th century. It would therefore make little sense to think or speak of any ‘zero wave’, as neither the word nor the concept existed in the Middle Ages. However, if we consider that issues voiced and addressed by later generations already appear in works by medieval authors, then, though anachronistic, the existence of a ‘zero wave’ of feminism may be an inspiring, thought-provoking possibility.

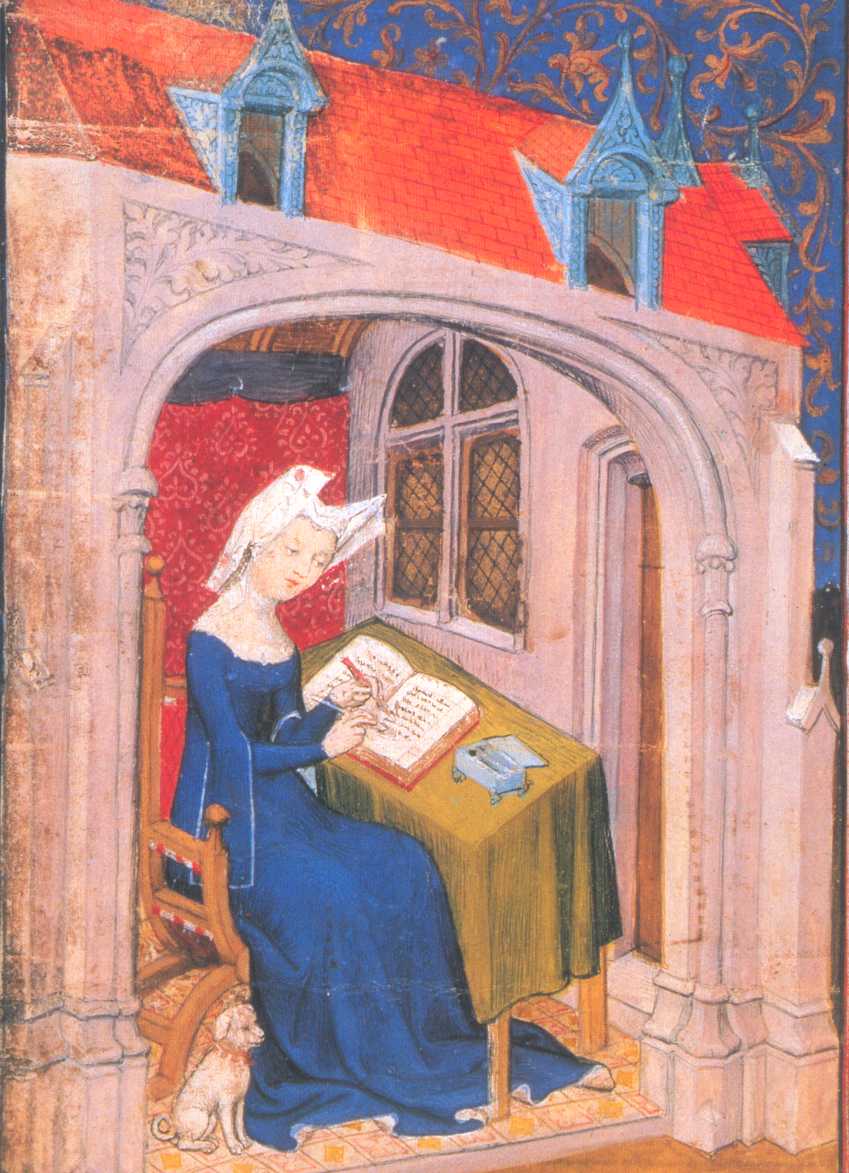

In order to illustrate the point, I shall refer to an abridged English edition of The Book of the City of Ladies (c.1405), entitled simply The City of Ladies (CL), by Christine de Pizan (1364-1430), a French female author of Italian ascent. In the back cover, one can read:

Pioneering female writer Christine de Pizan’s spirited defence of her sex against medieval misogyny and literary stereotypes is now recognized as one of the most important books in the history of feminism and offers a telling insight into the role of women in a man’s world. (Pizan, 2005)

As Eileen Power also notes,

It is not until the end of the fourteenth century that there appears a woman writer determined and able to plead for her sex and to take a stand against the prevalent denigration of women. That woman was (…) Christine de Pisan (…). Christine was (…) in many ways exceptional. She was a master of all the courtly conventions and was also able to make a living by her pen. (Power, 2000, p. 4)

Power evokes her thus:

Married before she was fifteen and left a widow without resources at twenty five, she had a long struggle to support her three children (…). She was indeed, as a French scholar puts it, the first woman who was ‘man of letters’ with no other support than what she could make by writing. Something of her own hard working life, honour of purpose and strength of conviction crept into her work, (…) especially into the two prose treatises, La Cité des Dames and Le Livre des Trois Vertus. (Power, 2000, pp. 23-24)2

All things considered, it can hardly be a coincidence that Christiane Klapisch-Zuber’s introduction starts precisely with a long reference to Christine de Pizan (1993, pp. 9-10).3 Moreover, her writings had an impact across the Channel, as Henrietta Leyser recalls:

Five of Christine’s works were translated into English in the fifteenth century. The Moral Proverbs of Christine, a book for children, that was translated by Anthony Woodville, tutor of Edward V, and published by Caxton in 1478, was the first by a woman to be printed in England. (Leyser, 1996, pp. 139-140)

Christine’s life and literary career orbited around noble social circles, both royal (Charles V, 1364-1380, and Charles VI, 1380-1422), and ducal (Burgundy); it should be stressed, by the way, that the original title was La Cité des Dames , not La Cité des Femmes … (our bold). In CL, Christine is also mentioned as the author of Letter of the God of Love and Letters on the Romance of the Rose (see below, n.4).

The narration takes place in the first person and the female narrator (also named Christine, or perhaps the author herself, considering the references to her works) acts like a pupil, full of doubts regarding something she can neither understand nor agree with: the cultural, social, intellectual, moral, and religious disregard of women and of female status vs. that of men:

(…) why on earth it was that so many men, both clerks and others, have said and continue to say and write such awful, damning things about women and their ways. (…) It is all manner of philosophers, poets and orators too numerous to mention, who (…) are unanimous in their view that female nature is wholly given up to vice. (…) I came to the conclusion that God had surely created a vile thing when He created woman. (…) I was astounded that such a fine craftsman could have wished to make such an appalling object which (…) is like a vessel in which all the sin and evil of the world has been collected and preserved. (Pizan, 2005, pp. 2-3)

The richness and length of misogynist literature, thought, and cultural tradition make this a topic too wide to be discussed, but I would suggest, for background reading, the anthology Woman Defamed and Woman Defended, edited by Alcuin Blamires,4 as well as Christiane Klapisch-Zuber (Dir.), História das Mulheres. A Idade Média, and Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate (especially pp. 166-170).

Disgusted with this rather poor view of her gender (or “sex”, as she puts it), Christine fails to grasp the reasons behind this deeply negative image, but she will be gradually enlightened through three allegorical characters presented as sisters: Lady Reason, Lady Rectitude, and Lady Justice. In the sense that Christine is taught through dialogue, CL displays a pedagogical structure, reminding us of the methods and practices of medieval scholasticism, rhetoric, and oratory, while illustrating, at the same time, the ability of allegory to materialize - and literally ‘embody’ - abstract entities, qualities, and values. After all, as C. S. Lewis (1898-1963) once wrote, “It is of the very nature of thought and language to represent what is immaterial in picturable terms” (Lewis, 1979, p. 44) and the point is expanded by Jeremy Tambling:

All types of language use incline towards allegory, whose existence indicates the impossibility of keeping an abstract conception, or construction, abstract. Thinking, which happens within figures of speech, becomes allegorical, giving a visual or linguistic shape to the abstract, which is perceived as personified and personifying, allegorical, creating allegory, and effacing the difference between the abstract and its embodiment as a figure. (Tambling, 2010, p. 14)5

Three other formal features should also be noted, the first of which is on the nature of these concepts and their complementary ‘partnership”:

In the twelfth century, writers began crafting allegories, texts with plural meanings. Characteristically, the device deployed was personification, giving life to abstract ideas by endowing them with a mask. Whereas allegoresis draws attention to hidden or abstract meanings, and allegory stresses that the surface meaning is not the ultimate quarry of interpretation, personification emphasizes the face which appears, which is, by definition, the surface meaning. In this way, allegory and personification work (…) in opposite modes. (Tambling, 2010, p. 171)

Secondly, apart from the allegorical genre/mode, CL dwells on the medieval literary and rhetorical convention of the exemplum(a), since the text provides a (re)collection of examples, mostly taken from Oriental and Classical Antiquity, legends, mythology, and the Bible.

Thirdly, CL adopts, and is built upon, the conventional form of the dream vision, a genre extremely popular throughout the Middle Ages, thanks to such 13th and 14th century works as Guillaume de Lorris’ and Jean de Meung’s Roman de la Rose, Dante’s Divina Commedia, the anonymous poems Pearl and Piers Plowman, and Chaucer’s ‘love visions’. Although CL is not a poem, I would argue that the tradition of the dream vision as a textual, verbal and/or pictorial resource can perfectly exist and be found outside (and beyond) poetry,6 since “The dream-vision (…) is particularly apt to express illumination through memory, through actual experience as revelation and through a kind of prophecy” (Brewer, 1983, pp. 168-169).

In order to approach Christine’s dream vision, let us quote from the text:

Sunk in these unhappy thoughts, my head bowed as if in shame and my eyes full of tears, I sat slumped against the arm of my chair with my cheek (…) on my hand. All of a sudden, I saw a beam of light, like the rays of the sun, shine down into my lap. Since it was too dark at that time of day for the sun to come into my study, I woke (…) as if from a deep sleep. I looked up to see where the light had come from and (…) saw before me three ladies, crowned and of majestic appearance, whose faces shone with a brightness that lit me up and everything else in the place. (Pizan, 2005, pp. 4-5; our bold)

Besides the purpose of dispelling Christine’s doubts and anxieties, thereby ‘illuminating’ her, literally and metaphorically, the ultimate goal of these characters is to build the City of Ladies and to make it inhabitable, each Lady playing her part in the process. In order to be effective, the symbolism of allegories and their personified characters must not only be materialized, but also spatialized, and, in fact, the vocabulary of medieval architecture, ‘engineering’, town planning, and defence7 is skilfully appropriated by/in the text, through images and metaphors which support and enhance the overall allegorical framework. Thus, whereas Lady Reason is responsible for starting the work and building the walls,8 Lady Rectitude puts up the buildings and invites some well-born women to move into the city,9 and Lady Justice concludes the whole process by bringing in the Virgin Mary herself.10 This is fully consonant with Mary’s status as a model or paradigm of female excellence, virtue, and sainthood, a view which pervades medieval religious literature in general and lyrics in particular.11 In fact, as Lady Reason argues, “(…) man has gained far more through Mary than he ever lost through Eve” (Pizan, 2005, p. 18).

Throughout the work, the three Ladies stress the importance of avoiding generalizations and manicheisms like “All women are good” vs. “All men are bad”, still stereotypically voiced at colloquial level. In fact, although six centuries have elapsed since CL was written, some observations, now obvious and commonsensical truisms, carry a distinctly modern ring, if transported back to their original, late medieval, context: see, for instance, the statement printed on the book cover: “Those men who have slandered the opposite sex out of envy have usually known women who were cleverer and more virtuous than they are” (Pizan, 2005, p. 12) or “It is he or she who is the more virtuous who is the superior being: human superiority or inferiority is not determined by sexual difference but by the degree to which one has perfected one’s nature and morals” (Pizan, 2005, p. 17). Christine’s emphasis on the importance of women’s education12 and the exposure of male verbal and physical abuse, assault, and aggression13 should likewise be highlighted.

Speaking of education in the broadest sense of the word, the upbringing and life experiences of Christine de Pizan may account for the selection of the noble females invited to live in the City of Ladies, although in the final chapter - almost a sermon, run through with advice like that found in manuals and guidebooks of manners and civility - Christine addresses all women (married, girls or widows). However, the cultural spectre of a traditional patriarchalism still looms behind statements like the following ones:

Those wives whose husbands are neither good nor bad should none the less thank the Lord that they’re not any worse. (…) Those wives with husbands that are wayward, sinful and cruel should do their best to tolerate them. (…) Even if their husbands are so steeped in sin that all their efforts come to nothing, these women’s souls will at least have benefited greatly from having shown such patience. (…) So, my ladies, be humble and long-suffering and the grace of God will be magnified in you. (Pizan, 2005, p. 120)

Although the (utopian?) idea of a city just for “ladies” (or women), comparable to the dream(s) and visions of an ideal or perfect commonwealth, may sound dystopian to (gentle)men who would be glad to live there as well, in parity of dignity, status, recognition, and citizenship, it seems appropriate to conclude with Christine’s own words:

Most honourable ladies, (…) the construction of our city is finally at an end. All of you who love virtue, glory and a fine reputation can now be lodged (…) inside its walls, not just women of the past but also those of the present and the future, for this city has been founded and built to accommodate all deserving women. (…) It will not only shelter you all, or (…) those of you who have proved yourselves to be worthy, but will also defend and protect you against your attackers and assailants, provided you look after it well. (Pizan, 2005, pp. 118-119)

And so indeed we should all - women and men, females and males -, even though the construction of such a city is truly never at an end.