From immemorial times, happiness or subjective well-being has merited the profound attention of philosophers and moralists, being considered the ultimate goal of human aspirations. Many predictors of happiness have been studied by different scientific disciplines, both objective and subjective, but only more recently interest in aversion and fear of happiness seem to be emerging (Joshanloo, 2013; Joshanloo et al., 2014; Joshanloo & Weijers, 2014).

Joshanloo and Weijers (2014) draw attention to the fact that studies on happiness and subjective well-being tend to underestimate the phenomenon they analyse, considering, without questioning, that happiness is one of the most important values in life for all individuals, when, in fact, this is not perceived as a supreme value in many cultures and, in some cultures, it is even perceived as aversive for the most diverse reasons (Amiri et al., 2019). For Joshanloo and Weijers (2014), happiness aversion consists of relatively stable beliefs that a certain type of happiness should be avoided, including: (1) beliefs about the different reasons for believing that people should be averse to happiness; (2) beliefs regarding the different extent to which people should be averse to happiness (e.g., the belief that happiness is something about which one can be somewhat cautious, very cautious, or extremely cautious); (3) beliefs associated with the different degrees of happiness about which people should be averse (e.g., being cautious only about extreme happiness); (4) beliefs regarding the different types of happiness that people should have an aversion to (e.g. happiness as pleasure rather than pain, happiness as satisfaction with life, happiness as worldly success, or all types of personal happiness) and (5) beliefs about the different relationships that an individual can have with happiness (e.g. being happy, expressing happiness, or actively seeking happiness). In an effort to contribute to a broader scientific view on happiness, Joshanloo et al. (2014) created the Fear of Happiness Scale (FHS), a scale that aims to assess the fear of happiness, consisting of 5 items, organized into a single factor, and has proven to have good reliability and validity. This scale that has been studied for at least 17 different countries, being validated for New Zealand, Iran, Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, India, Russia, Brazil, Pakistan and Kuwait (Joshanloo et al., 2014), for Turkey (Yildirim & Aziz, 2017) and, very recently for Portugal (Pacheco et al., 2019). All these studies were conducted from samples of university students (Joshanloo et al., 2014; Pacheco et al., 2019) or samples of community individuals consisting of fairly young adults (mean age 28 years) and mostly with higher education qualifications (Yildirim & Aziz, 2017). The FHS showed good reliability and validity in several studies, and, for almost all countries, it was organized into a single factor (Joshanloo et al., 2014; Pacheco et al., 2019; Yildirim, & Aziz, 2017). The present study aimed to contribute to the cultural and linguistic adaptation of the FHS for Portugal.

Method

Participants

Participants were 262 Portuguese adults, 87.4% female, aged between 18 and 82 (M = 33.50; SD = 13.37), with an education ranging from secondary school to PhD degree, having the majority of them a higher education (78.2%); 79% living in urban areas and 21% in rural areas.

Material

Participants answered to an assessment battery that included the following instruments:

a) Sociodemographic questionnaire, specifically developed for the present study with the purpose of collecting data regarding: gender, age, number of people living with them, level of education; and general perception of health, general perception of quality of life, satisfaction with the way they relate to family and friends (the latter 4 dimensions being assessed on a 5-point Likert-type scale, whereby the higher the value, the better the perception that the individual presents).

b) Mental Health Continuum- Short Form (MHC-SF) (Portuguese version by Fonte et al., 2020): This instrument is composed of 14 items intended to assess 3 components of well-being - emotional, social and psychological -, using a Likert-type scale with 6 response options. The Portuguese version showed good validity, good sensitivity and good reliability (Fonte et al., 2020), with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.95 in the present study.

c) Portuguese version of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS): This instrument assesses mental health, focusing only on its positive aspects. It consists of 14 items, organised into a single factor, and the original version has proven to have good psychometric qualities. The WEMWBS is being adapted to Portugal by Fonte et al. (study version). In this study, it had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.95.

d) Life Satisfaction Scale: This scale consists of five items which constitute statements regarding life satisfaction as a whole, to which the individual answers on a Likert-type scale of seven positions ("totally disagree" to "totally agree"). The version used in the present study is the one made available by Diener in his website (https://internal.psychology.illinois.edu/~ediener/SWLS.html). In the present study, this instrument showed a Cronbach's alpha of 0.88.

e) Anxiety, Depression and Stress Scale (DASS) (Portuguese version by Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2004): It consists of 21 items, organized into three subscales, each composed of 7 items, which assess symptoms associated with anxiety, depression and stress. It offers a 4-point Likert-type response scale (the response options vary between "it did not apply to me at all" and "it applied to me most of the time"). Higher values correspond to more negative affective states. The Portuguese version of the instrument showed good psychometric qualities (Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2004). In the present study, the Stress scale has a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92, the Depression scale has a Cronbach's alpha of 0.93 and the Anxiety scale has a Cronbach's alpha of 0.90.

f) Fear of Happiness Scale: The original scale was developed by Joshanloo (2013) and aims to assess the fear of happiness. The instrument is composed of 5 items, organized into a single factor, and has proven to have good reliability and validity, as well as versions adapted for other 14 countries (Joshanloo, 2013).

Procedure

It was requested the permission from the FHS original version authors to adapt it into Portuguese. A positive evaluation was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Fernando Pessoa University. Translation of the FHS into Portuguese was performed by two translators fluent in Portuguese and English and with scientific knowledge in the area under study. The two independent translations were then compared and discrepancies were explored, and possible changes were discussed in order to improve the quality of the translation. The consensus version produced was submitted to a cognitive analysis. Participants were invited through an institutional mailing list and social networks (Facebook) and answered the questionnaires after giving their free and informed consent.

Results

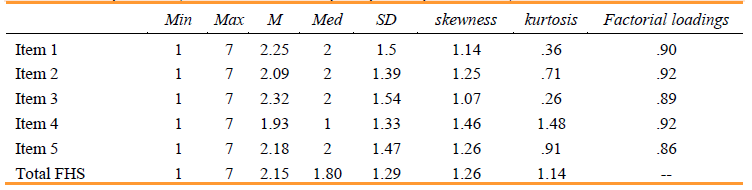

In order to analyse the sensitivity of the Portuguese version of the FHS, we performed a descriptive analysis of the values obtained in each item and in the total scale (Table 1). The values found in the items of the FHS vary between the extreme points of the scale (1 and 7) and the mean and median values are practically overlapping. The asymmetry values exceed unity for all items. The Portuguese version of the FHS has a Cronbach's alpha of .94 and the internal consistency does not benefit from the elimination of any item from the questionnaire.

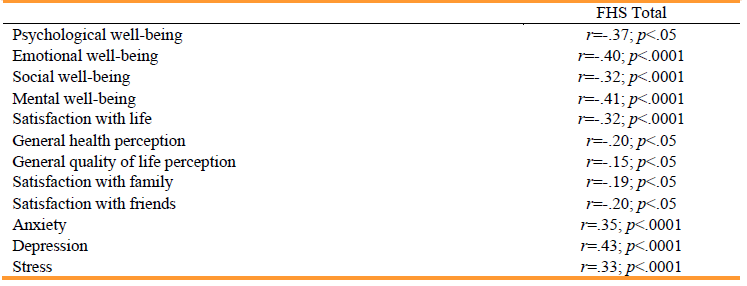

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (KMO=0.88) and Barlett's test of sphericity (χ2(10) = 1118.504, p<0.0001) were calculated. These results show a good suitability of the data for conducting factor analysis. Construct validity of the scale was assessed through principal components analysis method, which revealed that the scale is organised into a single factor that explains 80.29% of the variance, with high factor loadings for all items (Table 1). With the purpose of further analysing the instrument's internal validity, we calculated item-total correlations, corrected for overlap, finding moderate to strong associations: Item - r= .71; Item 2 - r=.78; Item 3 - r=.68; Item 4 - r=.79; Item 5 - r=.64. To assess convergent-discriminant external validity, the association between Total FHS and the administered measures of psychological well-being and psychological distress was analysed (Table 2).

Total FHS was found to be statistically significantly, negatively and weakly correlated with psychological well-being, social well-being, life satisfaction, overall health perception, overall perception of quality of life, satisfaction with how one relates to family and friends, but negatively and moderately correlated with emotional well-being and mental well-being. On the other hand, total FHS was found to be statistically significantly, positively and weakly correlated with anxiety and stress, but moderately correlated with depression.

Mann-Whitney U-test was calculated with the purpose of comparing participants of both genders regarding the FHS total score and each of the items included in this scale, and it was found that there were no statistically significant differences between both groups (p>0.05). Pearson's correlation analysis showed that there is a statistically significant, negative and weak correlation between age and total FHS (r=-.14; p<.05), between age and item 3 (r=-.16, p<0.05) and between age and item 5 (r=-.22, p<.01). One-Way Anova test and Bonferroni test revealed that there were statistically significant differences between participants with different educational qualifications regarding total FHS (F(4; 249)=3.331; p<.05 - secondary education> master degree), item 3 (F(4; 250)=4.30; p<.01- secondary education> master degree), and to item 5 (F(4; 250)=4.40; p<.01- secondary education> master degree) although not in the remaining items (p>.05). The lower the level of education of the individual, the higher is the value obtained in the total FHS (secondary education M=2.58; SD=1.80; upper secondary education M=1.60; SD=1.04), in item 3 (secondary education M=2.81; SD=1.83; upper secondary education M=1.88; SD=1.19) and in item 5 (secondary education M=2.83; SD=1.91; upper secondary education M=1.78; SD=1.12). Mann-Whitney U-test was calculated and it was found that there were no statistically significant differences between participants living in rural and urban environments regarding the total score obtained in the FHS, nor in any of the 5 items of this scale considered separately (p>0.05). Finally, Pearson's correlation was used to analyse whether there is a correlation between the number of people with whom the participant lives and fear of happiness, and it was found that there is no statistically significant correlation between this number and the score obtained in the total FHS, nor between this number and the items of the instrument considered separately.

Discussion

Regarding the distribution of values in the Portuguese version of the FHS, the answers to the several items are distributed between the extreme values of the response scale, with the mean and median values for the items and total score being very close. The mean value of the total FHS can be considered low, being close to that found for New Zealand, Iran, Korea, Russia (Joshanloo et al., 2014) and Portugal (Pacheco et al., 2019), higher than what was found in the population of Brazil and lower than in Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Japan, Taiwan, India, Kenya, Pakistan, Kuwait (Joshanloo et al., 2014) and Turkey (Yildirim & Aziz, 2017). The analysis of the distribution and of the asymmetry and kurtosis values for the items reveals that they do not present a normal distribution, what was expected given the Portuguese cultural context. These results overlap with those found by Pacheco et al. (2019) and differ from those found in Turkey, in which 4 out of 5 items revealed to present a normal distribution (Yildirim & Aziz, 2017). Nevertheless, in the Portuguese version under study, the dispersion of the answers across all the options offered suggests that it is a sensitive instrument, differentiating participants from each other in their symptomatic levels. In the version developed for Portugal by Pacheco et al. (2019), 3 of the 5 items did not reach the maximum value of the response scale, and the instrument seems to be less sensitive in the sample studied, what may be explained by the fact that the sample assessed by these authors consisted only of university students and not of a community sample.

Portuguese version of the FHS showed high reliability, being close to that found in the Portuguese version of Pacheco et al. (2019) and higher than that found in the English, Persian, Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Russian, and Portuguese (Brazil) versions tested in New Zealand, Iran, Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, India, Russia, Brazil, Kenya, Pakistan, and Kuwait, whose studies found Cronbach's alpha values ranging from .51 to .88 (Joshanloo et al, 2014) and higher than the Turkish version, which showed a Cronbach's alpha of .86 (Bülbül, 2018; Yildirim & Aziz, 2017).

The principal components analysis confirms the organization of the items into a single factor, with all items having high factor loadings. These results are in line with those found by Pacheco et al. (2019) in the Portuguese version and by Yildirim and Aziz (2017) and Bülbül (2018) in the Turkish version, as well as by Joshanloo et al. (2014) in 13 of the 14 countries that they studied, differing only from those found in India, where the unidimensional structure of the instrument was not confirmed. These results are supportive of the internal validity of the FHS and are supported by the moderate to high item-total correlations also found in the studies of Bülbül (2018) and Pacheco et al. (2019).

The higher the value obtained in the FHS, the lower psychological well-being, emotional well-being, social well-being, mental well-being, life satisfaction, overall perception of health and quality of life, and the higher symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress. The results support the external validity of the Portuguese version of the FHS under study, going in the same direction to those presented by Joshanloo et al. (2014), Pacheco et al. (2019) and Yildirim and Aziz (2017).

In parallel, results show that the higher the fear of happiness, the less satisfied people are with their family and friends and the higher levels of anxiety, depression and stress they have. These results are in line with what is stated by De Neve et al. (2013), who draw our attention to the fact that happiness can have a snowball effect on society, because those who are happy are more likely to bring happiness also to the lives of those around them and that those with low levels of positive affect and depression tend to distance themselves from others and have fewer rewarding relationships. Thus, it is possible that the fear of happiness is associated, in a very similar logic, with the quality and availability of social support networks.

In the present study, no differences were found between men and women regarding fear of happiness. Similar results were found for the Portuguese population (Pacheco et al., 2019) and for the total score in Turkish students (Şar et al., 2019), although in this case not for 4 of the questionnaire items, probably because of the cultural codes of this conservative society and the possibility of fear functioning as a coping strategy to alleviate adversity experienced in childhood. In the present study, the number of men studied was small, thus potential differences between female and male subjects in the Portuguese population should be further studied, and this analysis should always take into account aspects that may be relevant to the Portuguese culture.

It was found that there are no differences between individuals living in urban and rural environments regarding their fear of happiness. Piper (2015), in his study on happiness found that people living in the capital city in European countries have lower levels of happiness when compared to people living in other regions of the same country, and the reasons for this seem to differ between countries. In the current study however, once again, given the sample size, the results should be read with caution and the (in)existence of differences needs to be explored further in future studies.

The older the age, the lower the fear of happiness globally and the lower the beliefs that disasters often happen after good fortune and that excessive happiness has some bad consequences. Also, Pacheco et al. (2019) found a weak negative association between age and fear of happiness. These results seem to go along with the idea that happiness has a different meaning for the young compared to the elderly, and this change seems to be driven by a redirection of attention from the future to the present as people age. For example, Mogilner et al. (2011) found that younger people associate happiness with excitement, whereas older people tend to associate it with peace of mind. Fear being associated with anticipatory anxiety

The present study has some limitations that result either from the methodological options assumed or from the research design itself. The assessment battery was administered only through self-completion of an electronic form, which excluded all individuals with difficulties in completing questionnaires autonomously and requiring researchers' assistance, as well as all potential respondents without Internet access. In addition, the research design adopted, being cross-sectional, did not allow for a test-retest, thus it was not possible to assess the temporal stability of the instrument. These limitations will be easily overcome in future studies which combine different data collection procedures - face-to-face data collection and electronic data collection, and self-completion and completion assisted by researchers -, which will allow assessing more representative samples of the population, and which adopt a longitudinal design, pairing moments of assessment of the same participants at different moments in time. What constituted one of the weak points of the study is simultaneously a strong point of it. The response to the battery of evaluation through an electronic form frees participants from any constraint that could exist, in a culture where happiness is valued, to assume that they fear it.

This study allowed concluding that the Portuguese version of the FHS is a reliable, valid and sensitive self-report instrument, being a very brief and quick response measure, which can be used regardless of the individuals' area of residence and gender. The negative association with variables related to health and well-being and the positive association with psychopathological symptoms reinforce the importance of using measures such as this to identify the need to refer individuals for support and to plan more effective psychological intervention programmes.

Author’s contribution

Isabel Silva: Conceptualization; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project Administration; Resources; Validation; Writing of Original Draft; Writing - Revision and Edition.

Gloria Jólluskin: Conceptualization; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project Administration; Resources; Validation; Writing of Original Draft; Writing - Revision and Edition.