Finding the reasons why some party systems grow and mature with time while others remain fluid is an exercise that is both relevant and challenging. Though a constellation of macro-level factors - historical legacies, political institutions, economics, social structure - combine to explain the likelihood of institutionalisation or stabilisation over time1, there are also striking variations within and across regions (Sanches, 2018). The great diversity in the format and functioning of African party systems offers an excellent laboratory for revisiting the weight of existing explanations. In fact, while dominant parties and party systems have proliferated in countries such as South Africa, Namibia, Tanzania and Mozambique (Bogaards & Boucek, 2010), those in Madagascar, Kenya, Comoros and Zambia, just to name a few examples, have experienced massive vote shifts in elections, high fragmentation and the frequent emergence and success of new parties and independent candidates (Salih & Nordlund, 2007; Sanches, 2018). This article’s main goal is to understand why Madagascar’s party system has failed to institutionalise over repeated elections and remains as fluid as it was at the beginning of the Third Republic.

Existing scholarship shows that the passing of time has had little effect on party system development in Africa (Kuenzi & Lambright, 2001; Lindberg, 2007; Sanches, 2018), whereas authoritarian legacies have lasting effects (LeBas, 2011; Riedl, 2014). Thus, parties that, during authoritarianism, were able to rely on pre-existing organisational structures (LeBas, 2011) or to garner support by incorporating local elites (Riedl, 2014) were better able to endure over time. Though also acknowledging the relevance of these historical legacies, this study proposes a more dynamic framework.

The overall argument is that the way politics plays out in the present results from a mix between the legacies from prior historical periods, and the extent to which political elites are continuously able to make the playing field uneven (Levitsky & Way, 2010b). Consequently, where parties mainly rely on personal or material resources to build support (Levitsky & Way, 2013) and fail to effectively skew the competition in their favour (Levitsky & Way, 2010b) they will be more likely to fragment over time. This argument is tested in the case of Madagascar, which is relevant for at least three reasons.

First, it is one of the few countries with experience of a multi-party system prior to the start of the democratic wave in Africa in the early 1990s. Elections were competitive during the First Republic (1960-1975) and, although they became more restrictive in the Second Republic (1975-1993), parties were allowed to run as long as they supported the state’s socialist ideals by joining the National Front for the Defence of the Revolution (FNDR) dominated by the ruling Vanguard for the Malagasy Revolution (AREMA) (Thibaut, 1999, p. 533). Second, though the Third Republic (1993-2010) marked a transition to more democratic elections, at least formally, in practice the regime remained “competitive authoritarian” (Bogaards & Elischer, 2016, p. 12; Levitsky & Way, 2010a, p. 276), meaning that “electoral manipulation, unfair media access, abuse of state resources, and varying degrees of harassment and violence” often skewed the playing field in favour of incumbents (Levitsky & Way, 2010a). Third, Madagascar is often depicted as an “unstable competitive authoritarian regime” characterised by weak parties, and recurrent political crises (Bogaards & Elischer, 2016; Levitsky & Way, 2010a). In this sense, it resembles other cases in the continent (e.g. Malawi, Kenya and Zambia).

The study is structured as follows: The theoretical section highlights the major trends in electoral politics in Africa since the 1990s and presents the theoretical framework. Then Madagascar’s key political and historical developments are briefly described. The following sections examine the role of authoritarian legacies in party building and mobilisation strategies, as well as the tactics used by incumbents to skew the playing field. Drawing on multiple sources of data including electoral data, election observation reports and legislation, our findings show that leadership centralisation, ethnicity, personalism and clientelism shaped party formation during the authoritarian era and beyond; and that incumbents use their advantage to create asymmetries in access to resources, media and law. Interestingly, however, the analysis also indicates that the strategies used to skew the playing field only produce short term gains; they do not prevent rotation in power in a subsequent election. This set of findings contributes to an understanding of “competitive authoritarianism” in contexts of high instability, weak parties, weak state capacity and ineffective power structures. This will be discussed further in the concluding section.

Understanding party systems in Africa

African party systems are often characterised by high levels of electoral and legislative volatility, loose linkages with society and low legitimacy accorded to elections and political parties (Basedau, 2007; Kuenzi & Lambright, 2001; Lindberg, 2007; Riedl, 2014; Sanches, 2018). However, there are also striking cross-country variations. Of a sample of democratic countries, Ghana and Cabo Verde feature stable party systems in which two organisationally strong parties truly aspire to form a government, while dominant parties in Botswana and South Africa have never experienced loss of power, and Mauritius has seen a succession of various coalitions (Resnick, 2011; Sanches, 2018). In the group of authoritarian regimes - e.g. Angola, Gambia, Gabon, Zimbabwe and Equatorial Guinea - dominant parties and party systems are more prevalent. Incumbents often rely on multiparty elections, parliaments and coercion to prolong their authoritarian rule (Bogaards & Elischer, 2016). Finally, in the cluster of hybrid regimes2 - e.g. Zambia, Comoros, Madagascar and Kenya - party systems have remained unstable since the first multiparty elections (Sanches, 2018). These are just some instances, from a broader sample, of the diversity and dynamics of African party systems.

To explain this diversity, scholars have looked at a constellation of structural, institutional and economic factors. Ethnicity is assumed to be the quintessential social cleavage in Africa and to strongly influence party competition (Erdmann, 2007). Most relevant parties emerged out of crystallised territorial and ethnic cleavages (Manning, 2005) and rely on these identities to build support (Salih & Nordlund, 2007). Furthermore, it has been shown that a party system can institutionalise if parties are able to cut across ethnic divisions and construct winning coalitions (Ferree, 2010; Riedl, 2014; Sanches, 2018; Weghorst & Bernhard, 2014), while political institutions and the economy generally have a small and unsystematic effect. In any case, studies show that presidential and proportional systems, as well as economic growth, engender higher levels of party system stability or institutionalisation (Ferree, 2010; Kuenzi et al., 2017; Riedl, 2014; Sanches, 2018).

A final set of explanations relevant to this study highlights the role of authoritarian legacies - specifically “behavioural patterns, rules, relationships, social and political situations, and also norms, procedures and institutions, either introduced or strongly and patently strengthened by the immediately preceding authoritarian regime” (Morlino, 2010, p. 508). Thus, LeBas (2011) argues that, where the authoritarian state has allowed the existence of mobilising structures such as trade unions, they have served as focal points for the formation of strong opposition parties during the transition, and this has promoted institutionalisation over time (LeBas, 2011, p. 5). Riedl (2014), in turn, demonstrates how power accumulation strategies during the authoritarian era allowed incumbent parties to survive the transition and beyond: rulers who had incorporated the local elites enjoyed more support and were able to control the transition and build more institutionalised party systems. Loxton’s (2018) study on authoritarian successor parties worldwide showcases a panoply of forms of authoritarian legacies including “(1) a party brand, (2) territorial organization, (3) clientelistic networks, (4) source of party finance, and (5) source of party cohesion” (Loxton, 2018, p. 10). Grzymala-Busse, in turn, explores “usable pasts”, i.e. “the historical record of party accomplishments to which the elites can point, and the public perceptions of this record”, and “portable skills”, i.e. “the expertise and administrative experiences gained in the previous regime” (Grzymala-Busse, 2002, p. 5).

In Madagascar, the absence of a strong historical party, the frequent rotation in power, and the weakness of the state (Levitsky & Way, 2010a, p. 276) suggest that parties do not benefit much from “usable pasts” or “portable skills”. Furthermore, they cannot count on strong economic performance, an effective coercive apparatus or a stable patronage machine to avoid intra-party conflict and guarantee their survival (Mukonoweshuro, 1990, p. 385; Levitsky & Way, 2010a, p. 267). Thus, to better understand the fluidity of the Malagasy party system, we focus on authoritarian legacies of party formation and their sources of elite cohesion and the clientelistic networks. Leadership centralisation, ethnicity, personalism and clientelism will be discussed as the key (authoritarian) behavioural patterns structuring party formation and development.

However, since historical legacies fade over time, it is important to consider how party elites continuously reshape the rules of the game to gain leverage over their opponents. A “level playing field” is part of any definition of democracy, but “competitive authoritarian regimes” are characterised by an uneven playing field where “1) state institutions are widely abused for partisan ends; 2) the incumbent party is systematically favoured at the expense of the opposition; and 3) the opposition’s ability to organize and compete in elections is seriously handicapped” (Levitsky & Way, 2010b). The analysis here explores how incumbents create asymmetries in the playing field by limiting access to resources, the media and the law (Levitsky & Way, 2010b); however, and most importantly, it also shows the limits of these tactics.

Though the analysis centres on authoritarian legacies and elites’ tactics, it does not neglect the importance of other variables. For instance, it has been argued that, where state capacity is lower, “elections are more likely to spin out of control, forcing the regime to turn to more blatant forms of fraud or large-scale violence, which tends to cause regime destabilisation” (Croissant & Hellman, 2018, p. 4). The Malagasy party system functions in an environment of low organisational power, weak state infrastructures and coercive capacity, which have left governments more vulnerable to domestic and foreign pressures (Levitsky & Way, 2010a, p. 277). Overall political elites have been unable to reduce political uncertainty and structure the competition in a predictable way.

Madagascar’s Third Republic: electoral competition in the “new democratic era”

After independence from France in 1960, the First Malagasy Republic was led by the Social Democratic Party (PSD) and its leader, Philibert Tsiranana, who ruled for over a decade before he was forced to resign and hand over power to the military. After three years of military rule, in 1975 former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Didier Ratsiraka, was installed as president, marking the beginning of the Second Republic. Ratsiraka’s first period as president (1975-1993) was defined by its political commitment to a “Leninist scientific socialism”, demonstrated through drastic reforms of political and economic institutions (Marcus, 2004, p. 2). The “socialist turn” experienced on the island was also felt at the party system level because parties were, indeed, allowed to run as long as they supported the state’s socialist ideals by joining the FNDR3 (Thibaut, 1999). In this context, the AREMA, created by Ratsiraka himself, was, unsurprisingly, the strongest FNDR party, often winning elections by a landslide4. However, despite its strong outer appearance, AREMA was lacking “organizational and institutional capacity” and was “weakly rooted in society” (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison, 2005, p. 501).

In addition, the state remained weak and poorly implanted in the countryside; Ratsiraka failed to establish control over society and the economy deteriorated under his incumbency (Levistky & Way, 2010, p. 277). By the end of the 1980s, socialist policies had been laid to rest with the helping hand of the Bretton Woods institutions, but crippling debt and economic underperformance still plagued the country, leading to a rise in political opposition that was able to challenge the ruler.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the coming of the Third Wave of democratisation to Africa made it almost impossible for Ratsiraka to remain in power and, in 1991, almost half a million strikers marched in Antananarivo5 and completely paralysed the economy, forcing the president, later that year, to sign the Panorama Convention and allow a transitional government to take over. The following year, the constitution that provided for a semi-presidential system was approved via referendum, marking the beginning of the Third Republic. After the senate had been abolished under the Second Republic, leaving the National Assembly as the unicameral parliament, the new republic reinstated bicameralism and defined a mixed electoral system to elect members of parliament. As for the senate, two-thirds of senators are indirectly elected and one-third appointed by the president. The president is elected in a two-round system.

Three critical moments mark the political shifts in the island-state over the last three decades or so: first, the 1992/1993 presidential elections and the 1993 legislative elections marked the beginning of multiparty elections in Madagascar (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison, 2005, pp. 501-502); second, the post-electoral crisis of 2001-2002 put an end to Ratsiraka’s rule and resulted in the rise of Marc Ravalomanana; finally, the 2009 coup d’état led to the resignation of the democratically elected president Marc Ravalomanana and consequent political crisis that signalled the end of the Third Republic and ultimately led to the consolidation of Andry Rajoelina.

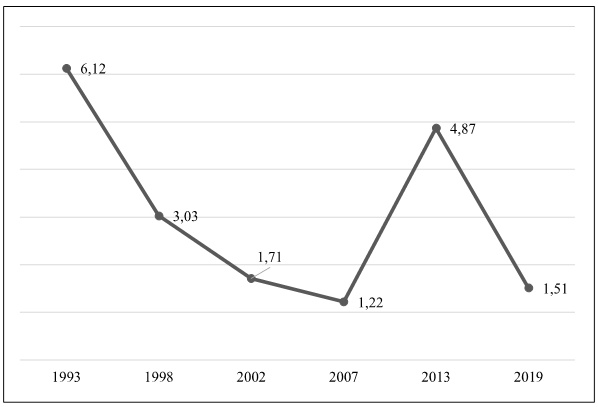

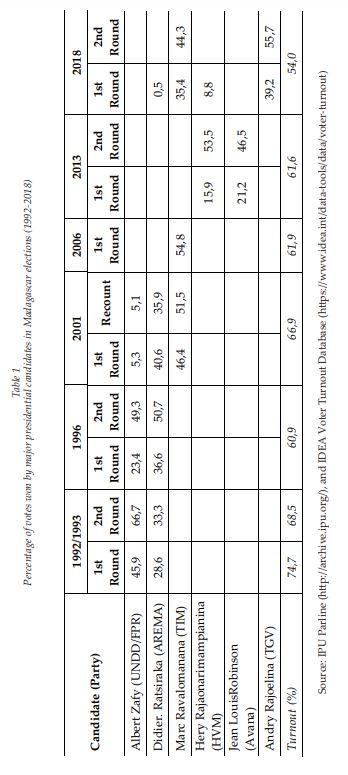

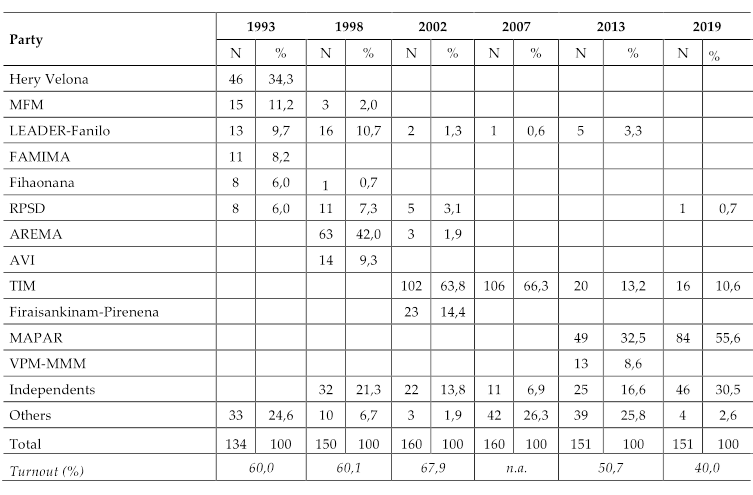

Though Madagascar is a semi-presidential regime, presidential elections are the most relevant and mark the tone of electoral competition. Legislative elections have taken place after the presidential race since the outset of democratic transition, which means they have a confirmatory status and mainly serve to secure parliamentary support for the incumbent president. This “honeymoon” between presidential and parliamentary elections is confirmed by the fact that the party (or allies) that support the winning presidential candidate eventually win a majority in the national assembly elections. However, competition is far from predictable: there is frequent rotation in power at both the parliament and presidency levels, independent office seekers easily break through (Table 1 and Table 2), and the effective number of parliamentary parties fluctuates significantly (Figure 1).

Table 1 Percentage of votes won by major presidential candidates in Madagascar elections (1992-2018)

Source: IPU Parline (http://archive.ipu.org/), and IDEA Voter Turnout Database (https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/voter-turnout)

Table 2 Number and percentage of votes per party in parliamentary elections in Madagascar (1993-2019)

Source: IPU Parline (http://archive.ipu.org/), and IDEA Voter Turnout Database (https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/voter-turnout)

In the first three presidential races, Albert Zafy, Didier Ratsiraka and Marc Ravalomanana were successively elected and managed to secure parliamentary support. Thus, in the 1993 parliamentary elections the political grouping with the most votes was the Hery Velona, an alliance of President Zafy, the Rally for Social Democracy (RPSD) and the Movement for Proletarian Power (MFM). Zafy was eventually impeached for violation of the constitution but contested the 1996 election. His main challenger was the former authoritarian leader Ratsiraka, who eventually won the race in the second round (Thibaut, 1999, p. 533). The coalition Hery Velona was disbanded, paving the way for a clear victory for AREMA (Table 1).

In 2001, Marc Ravalomanana won the presidential elections amid great controversy. After it was reported that Ravalomanana was leading the polls with over 50% of the vote, the National Electoral Committee (CNE) opted to continue the count behind closed doors, raising some concerns. When the High Constitutional Court (HCC) announced the results, neither Ravalomanana nor Ratsiraka had secured a majority of the votes, meaning that, under the constitution, a second round was needed. Thousands of protesters took to the streets in support of Ravalomanana, demanding a recount, and he decided to act on the will of the people and declared himself president. In response, Ratsiraka declared a State of Emergency, put the nation under Martial Law and established his political stronghold, Toamasina, as the new “capital”. With the country divided in two, oil and food supplies to Antananarivo cut off and increasingly violent protests, the nation was on the brink of civil war when Ratsiraka and Ravalomanana agreed on a recount. Following these events, a newly constituted HCC announced that Ravalomanana had won with 51.46% of the vote (compared with Ratsiraka’s 35.90%) and the new president was inaugurated in May. Unwilling to accept the results, Ratsiraka fled to France, putting an end to the civil unrest (Marcus, 2004, pp. 6-11).

The 2002 legislative elections that followed the national crisis proved the widespread support for Ravalomanana’s party, I Love Madagascar (TIM): TIM won 102 of the 156 seats in parliament whereas their close allies, Firaisankinam-Pirenena, won 20 seats. With independent candidates taking over 23 seats, no other party made much of an impact. Confirming Ratsiraka’s downfall, AREMA took only three seats, all of them elected from Toamasina. It should be noted that, prior to the election, AREMA was divided in two factions, with one of them (“Front du Refus”) boycotting the elections (European Parliament, 2003, p. 5). Despite some success in former elections, MFM had only two successful candidates and LEADER-Fanilo only one (European Parliament, 2003). The rapid rise of TIM and the equally sudden fall of some of the traditional parties (such as AREMA, LEADER-Fanilo and MFM) demonstrates the weak institutionalisation of political parties in Madagascar and points to the country’s political instability (Marcus, 2010).

The following cycle of elections witnessed a repetition of this trend: Ravalomanana won the 2006 presidential race and his party TIM increased its share of seats to 66.3% in the 2007 parliamentary elections. Between these two elections, there was a national referendum that sought, among other things, to increase presidential powers and redefine the island’s administrative divisions (Marcus, 2010, p. 126). As the 2007 referendum shows, Ravalomanana used his second presidential term to extend his power and neopatrimonial network. Authoritarianism increased under Ravalomanana but he faced strong contestation. Andry Rajoelina, the mayor of Antananarivo, and founder of the political party Determined Malagasy Youth (TGV), gained visibility after criticising a deal that the government intended to seal with Daewoo, which implied leasing about 1.3 million hectares of Malagasy land without clear benefits to the people (Marcus, 2010, p. 123).

In late 2008, when the president ordered the closing of Rajoelina’s television station VIVA after it broadcast an interview featuring former president Ratsiraka, the young mayor used this to incite thousands of Malagasy to take to the streets of the capital. The protests faced violent repression and dozens of citizens were reported dead or injured. The president’s unwillingness to reopen the TV station led Rajoelina to declare himself president of a transitional government, which had no constitutional support. The president reacted by firing him from the office of mayor of Antananarivo, which contributed to further deterioration of Ravalomanana’s support amongst the general population and, more importantly, the military elites of the country. After the mutiny of a small group of soldiers, the military decided to take action, forcing Ravalomanana to hand over power to the military in March 2009 - power was then handed Rajoelina, who became, officially, the president of the High Transitional Authority (HAT) (Cawthra, 2010, p. 14; The Carter Center, 2013, pp. 17-18).

While this was widely perceived as a coup d’état, Rajoelina headed the HAT government until 2013. He proposed a new constitution to enhance presidential powers but, as in the past, lack of transparency meant that voters were not fully aware of what this new constitution implied, causing several opposition parties to boycott the act. Therefore, the constitution that inaugurated the Fourth Republic was approved by 74.2% of the vote. Ahead of the 2013 elections, tensions continued to escalate between Ravalomanana and Rajoelina, until the mediation process opted for what they called a “ni ni” solution, a mutual agreement that excluded both of them from the future election and resulted in a “proxy election”: Ravalomanana chose Jean-Louis Robinson, a former World Health Organization official, to represent his interests and Rajoelina picked former finance minister, Hery Rajaonarimampianina (The Carter Center, 2013, pp. 17-18).

A record 33 candidates participated in the presidential race and the results were widely spread. Robinson (Ravalomanana’s candidate) led the first round of voting with only 21.2% of the vote and Rajaonarimampianina followed with 15.9%. Neither Robinson nor Rajaonarimampianina were supported by Ravalomanana’s TIM or Rajoelina’s TGV. Instead, the leading candidates were backed by the newly-formed New Forces for Madagascar (Rajaonarimampianina) and Avana (Robinson). Despite leading the first round, Robinson lost the election to Rajaonarimampianina in a tight second round vote.

The 2013 post-crisis general elections were, in some way, a return to normalcy. The political movements behind each candidate gathered most of the vote, with a clear victory to Miaraka Aminny Andry Rajoelina (MAPAR), winning 49 seats against TIM’s 20 seats. Rajaonarimampianina became the only president in Madagascar’s history to win a presidential election without the corresponding party winning (or even contending) the legislative election. Opposition from smaller parties seemed to have increased again as new parties and independent candidates continued to flourish. In office, Rajaonarimampianina proceeded to distance himself politically from his supporter Rajoelina (Bozzini, 2018). However, this did not translate into political stability for the nation. Three different prime-ministers were appointed in the course of four years and the president himself suffered an attempted impeachment in May 2015 (Freedom House, 2016).

Elections for the senate and local government were only held at the end of 2015, about two years into Rajaonarimampianina’s presidency, after which the government was, for the first time since the 2009 coup d’état, fully in place. The president’s party polled about 65% of the vote in local elections and he himself appointed, as the constitution allows, one-third of the senate. Rajoelina along with MAPAR became a strong political voice in opposition, regularly asking the president to step down and urging early elections. The “honeymoon” between presidential and parliamentary elections was eventually restored as Andry Rajoelina would be elected president in the 2018 presidential race while his MAPAR6 gained 84 of the 151 parliamentary seats in 2019. Ravalomanana’s TIM was down to 16 and 46 independent candidates entered parliament. Overall, elections in Madagascar show repeated instability, unpredictability, frequent political change and significant gains for new and president-led parties, and independent office seekers. The following sections explore the factors underlying these dynamics.

Authoritarian legacies

The most relevant parties that have emerged since independence were created by political elites, bringing together divergent interests. Given the absence of mobilising structures, such as strong trade unions, and of clear ideologies and programs, political parties had to grow from scratch, on the basis of calculations by the elites. Hence, political parties in Madagascar emerged from above, created by influential or charismatic leaders, and mainly relied on ethnicity, personalism and neopatrimonialism to build internal and external support. This can be seen in the independence period and throughout the authoritarian era but, in addition, current political parties in Madagascar are extremely dependent on the wealth and prestige of their leader, and few survive if their leader loses the presidency. Parties have shown little capacity to strengthen their grass-roots organisation and interparty competition is generally more defined by ethnic, personal and clientelistic ties than by ideologies.

In terms of ideologies, AREMA aimed to implement a program of “scientific socialism” but the party lacked the institutional capacity to meet its goals. Neopatrimonial in nature, the true strength of AREMA was almost solely based on the figure of Ratsiraka and his personal connections, as its support base derived directly from the president’s patronage networks, partially made up of former PSD supporters, including prominent military figures, businessmen, rich families and local elites from various provinces. As a consequence, many close friends or relatives of the president were seen occupying significant political positions during this period. Nicknamed “Deba” (which translates as “Big Man”), Ratsiraka was of Betsimisiraka ethnicity and had his political stronghold in the coastal Toamasina, away from the capital city. The “Red Admiral”7 was, for a period, able use his decentralising policies to juggle the island’s ethnic divides, stripping the Antananarivo-based Merina ethnic group of its traditional control of both the administration and the economy but appointing close Merina acquaintances to important governmental roles. The apparent decentralisation was, however, a strategy that made it easier for the executive to make top-down decisions. Even when Ratsiraka’s popularity began to fall, considerable influxes of foreign aid from international partners (in response to the country’s bankruptcy) were largely perceived as a gesture of support for the island’s authoritarian leader. However, strong perceptions of corruption and the increasing marginalisation of the Merina people were seen as contributing significantly to the decay of national unity and support for the regime (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison, 2005, p. 501; The World Bank, 2010, p. 12).

Despite losing the founding presidential/parliamentary elections, Ratsiraka and AREMA returned to power in 1996/1998. Ratsiraka, however, following the same old way of doing politics, proceeded to re-establish himself in the coastal provinces as part of a long-term strategy. Moreover, reverting to his neopatrimonial roots, he once again put his close friends and relatives in significant political positions and helped them achieve control over the economy by providing commercial and industrial opportunities (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison, 2005, p. 503).

Besides AREMA, two other noteworthy parties emerged on the Madagascar scene: Albert Zafy’s Hery Velona and Marc Ravalomanana’s TIM somehow built their strengths on their leaders’ neopatrimonial networks (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison, 2005). Being essentially an “electoralist catch-all party”, the Hery Velona suffered from serious “internal heterogeneity” and lacked a coherent ideology, which impeded stable government (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison, 2005, pp. 502-503). When his turn came, Zafy followed the pattern of most (if not all) Malagasy presidents, taking clear advantage of the country’s weak democratic institutions to consolidate his power8. He turned Hery Velona into his own neopatrimonial network, much as Ratsiraka had with AREMA, but his efforts to impede attempts to amend the constitution in order to limit presidential powers were generally not well received, and he was impeached in 1996 on charges of corruption (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison, 2005, pp. 502-504; Thibaut, 1999, p. 533).

In Malagasy political parties, personalism and neopatrimonialism cannot be read separate from ethnicity. The Merina-Côtier9 ethnic divide has shaped politics in the country since colonial times and political leaders continue to exploit it. It has served as the political pretext for the creation of the PSD, and later for AREMA. The two parties had also in common the fact that they were a “loose coalition of divergent interests” (Allen & Covell, 2005). AREMA was the creation of Didier Ratsiraka, a côtier from the Betsimisaraka ethnic group. Côtier resentment of Merina was just one of the strategies used by Ratsiraka to gain political support, as in “Antananarivo-centred dissent and in his unsuccessful calls for ‘federal’ secession in 1992 and 2002” (Allen & Covell, 2005, p. 68).

Scholars like Cole (1998) also point to the ethnic dimension behind the rise of Hery Velona. Capitalising on the failure of Ratsiraka’s policies to benefit the urban population, Hery Velona’s support was mostly based in the Antananarivo area and, according to Cole, they “spoke with enthusiasm about the upcoming changes”, referring to the 1992/1993 elections. On other parts of the island, AREMA would actually promote ethnic tensions, claiming that the Merina, whose interests were represented by Hery Velona, would enslave the coastal people10, “were they given the opportunity by this election” (Cole, 1998, p. 617). Later, during the 2001/2002 political crisis, Ratsiraka played the ethnic card again, going as far as inciting “his supporters to pretend to be Merina and threaten côtier groups”, in an attempt give the appearance of an ethnic conflict (Marcus, 2004, pp. 9-10).

Considering the Malagasy party system and the country’s historical ethnic divide, one cannot help but acknowledge the immense success of Marc Ravalomanana as a candidate, and of his party. Before Ravalomanana entered the political scene, it was very unlikely that a Merina candidate would win a presidential election, mostly because it was very unrealistic to expect him to win outside the Antananarivo province. In reality, the Merina leader went on to defeat Ratsiraka in several coastal provinces, including some that had historically voted against Merina candidates and, even though he lost there, he did manage to achieve a good result in his rival’s hometown. Even though Ratsiraka had “spent his entire second presidency manipulating institutions and deepening his personal networks”, Ravalomanana prevailed in the election for three main reasons: first, the unpopularity of his opponent and the population’s growing demand for a change; second, his role as a businessman, with a liberal approach to the economy and the power to make a real change; and finally, his nationalist campaign, which, during a time of crisis, urged the various ethnic groups to stand together for the country’s greater good. We cannot, however, underestimate the importance of Ravalomanana’s dairy company Tiko, one of the country’s biggest and most internationalised companies, which was a fundamental tool in the establishment of Ravalomanana and TIM, being not only a considerable source of party funding but also the place where Ravalomanana recruited his personal elite. After his election, the senate saw Ratsiraka’s supporters replaced by individuals who served both the party and the company. Tiko was thus a means of strengthening the new party before the elections and the neopatrimonial base that would hold it together (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison, 2005, pp. 504-508). As we shall see in the next section, Tiko was also important in the way Ravalomanana skewed the playing field.

An uneven playing field

Since the beginning of the Third Republic, all the presidents have changed the constitution to increase their power, but they resort to other strategies to gain leverage over their opponents, and this is particularly evident during elections. The political playing field may be uneven in a variety of ways, but three are of particular importance: unequal access to resources, the media, and the law (Levitsky & Way, 2010b). When the incumbent is able either to easily “appropriate state resources” and “make widespread partisan use of public “means” or to fund personal businesses or party-owned enterprises through “public credit, concessions, licensing, privatization or other policy instruments”, it means the opposition cannot compete on a level playing field (Levitsky & Way, 2010b, p. 58).

In Madagascar politics is often contested by very wealthy individuals, which negates asymmetries in access to state resources. As in most African countries, access to state resources is important, and generally benefits the incumbent party, but there are alternative pathways to power for those in opposition. Parties created by wealthy leaders can rely on the leader’s resource base, and neopatrimonial networks to build support and this has been one of the keys to incumbents keeping the playing field uneven, but it has also made it possible for some new contenders successfully to challenge incumbents.

Before entering politics as mayor of Antananarivo in 1999, Ravalomanana was already a household name amongst the business elite, a “self-made millionaire” who owned a big company and had just founded his own party (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison, 2005, p. 506). Despite being new to presidential elections, Ravalomanana had, in Tiko, a robust campaign machine at his disposal: on the one hand, it was the source of his revenue, allowing him to spend huge amounts of money on his campaign; on the other, Tiko’s merchandise could be found throughout the country, even in the most remote villages, making Ravalomanana’s brand and name well-known throughout the territory. Traditionally, such breadth of coverage has been problematic for many candidates. The island’s size and the lack of an efficient transport system has made it very difficult for every contender to campaign in every province, and it made this millionaire’s personal helicopter a useful asset (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison, 2005; Moser, 2004, p. 8). In an attempt to skew the playing field, Ratsiraka increased the candidacy fees, making it very difficult for smaller/independent candidates to participate (Marcus, 2004, pp. 5-6), but this strategy could not fend off candidates as wealthy as Ravalomanana, who successfully challenged Ratsiraka’s presidency.

With regard to disparities in resources, the situation only worsened when the new president took office, as Ravalomanana’s immense private wealth had merged with state resources. The Tiko Group’s subsidiaries constantly received favourable treatment in awarding government contracts, working closely with foreign companies and purchasing privatised state companies, and it expanded exponentially11 during Ravalomanana’s first presidency. And the overlap between the Tiko elite and the TIM elite, the line between private and public became increasingly blurred. Tiko’s dominance also had consequences for the already waning opposition, which could be more easily punished and weakened by being excluded by the government from economic opportunities (Marcus, 2010, p. 122).

With the merging of public and private and TIM and Tiko, Ravalomanana managed to increase the imbalance on the playing field far more than it had been under Ratsiraka and almost to extinguish opposition. Candidates were expected not only to pay high fees to participate in elections, but also to print their own ballots, adding to the cost of the electoral process. This excluded several contenders who could not afford to run, with some not having the resources to print enough ballots for every constituency, and it benefitted those with more financial resources (EISA, 2007). As a result, Ravalomanana became the first (and so far only) candidate, since the end of the Second Republic, to win a presidential election without going to a second round, having secured over 50% of the vote in the first round.

Despite a very uneven playing field during Ravalomanana’s tenure as president, it was still not enough to extend his rule over the island, as another strong contender had emerged: Andry Rajoelina, the young founder of the TGV party and owner of the VIVA radio and television station, among other enterprises. The similarities between Rajoelina and Ravalomanana were undeniable: both were self-made Merina millionaires who had become mayors of the capital amid the presidency of an increasingly authoritarian leader and both owned media enterprises that were crucial for voicing criticism and to mobilising the population.

In the elections that followed (2013 and 2019), the issues concerning the lack of party/campaign finance regulation and of transparency regarding each candidate’s spending12 continued, unsurprisingly, to be pointed out as one of the biggest flaws in the Malagasy electoral process (The Carter Center, 2013, pp. 28-36).

On a different level, if equal access to resources is necessary for fair elections, the same goes for equal access to the media. Levitsky and Way’s (2010b) understanding of what makes access to the media unequal is perfectly illustrated in Madagascar: the playing field is skewed if “the state either monopolizes broadcast media or operates the only television and radio stations with a national audience” (Levitsky & Way, 2010b, p. 59). During Madagascar’s multiparty history, unequal access to media has seen no dramatic changes. The president and the ruling party usually dominate public media (television and radio), which is the only media that covers the whole territory. Private and print media have traditionally been free from government-imposed restrictions but generally lack the capacity to reach broader audiences (EISA, 2008). During the 2001 presidential elections, the government imposed restrictions on the media, ensuring that only the news agencies chosen by Ratsiraka himself could cover the election (Marcus, 2004, pp. 6-8). As seen in Ravalomanana’s and Rajoelina’s paths to political power, access to media is crucial for mustering political support and these two candidates benefited from having their own television/radio stations, when, as members of the opposition, their access to the media was limited.

Finally, even if access to state resources and to the media are equal between incumbent and opposition, a playing field cannot be levelled if there is not equal access to the law. In this scenario, incumbents “control the judiciary, the electoral authorities, and other nominally independent arbiters”, removing their autonomy and impartiality, making them unreliable and using them to harass the opposition. The incumbent enjoys legal impunity, while the opposition cannot denounce injustice effectively (Levitsky & Way, 2010b, p. 60). Throughout Madagascar’s Third Republic there have been several instances when the institutions lacked the required autonomy to make decisions fully independent from the executive or when the law was deployed to hinder the opposition.

For example, while the High Constitutional Court (HCC) remained independent of the executive during Zafy’s administration, even allowing for his impeachment, Ratsiraka’s return to power brought a decrease in the autonomy of the political institutions. During his presidency, the HCC was used to crush his opposition in the 1999 local elections, by altering the results “through a series of controversial court decisions” that allowed AREMA and its allies to win (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison, 2005, pp. 502-504). On another occasion, at the 2001 presidential elections, when the Committee to Elect Marc Ravalomanana (KMMR) reported that he was leading the polls with 54.95% of the vote, Ratsiraka pressured the CNE to continue the voting process behind closed doors. The result did not give Ravalomanana immediate victory13, although both the KMMR initial count and the Consortium of Election Observers (CNOE), a civil society group, gave Ravalomanana over 50% of the vote. The discrepancy in figures produced by the different bodies was suspicious and raised questions about the CNE’s autonomy, and the absence of international observers only diminished the credibility of the results. With the other bodies unable to access the remaining third of the votes, the results were highly controversial. It was up to the HCC to publish the official results, but the composition of the HCC had been changed by order of the incumbent a few months before, making the HCC obviously more likely to support Ratsiraka. In the same elections, Ravalomanana tried unsuccessfully to petition the HCC to disqualify Ratsiraka on the grounds that he had violated the electoral law, namely by using state resources for his personal campaign (Marcus, 2004, pp. 6-8).

Ravalomanana, too, has used the HCC to fend off potential challengers. In the 2006 presidential election, the HCC disqualified four candidates on different grounds, three of whom were widely regarded as Ravalomanana’s strongest opponents: exiled opposition leader and former deputy prime-minister under Ratsiraka, Pierrot Rajaonarivelo14, who was not allowed to return to Madagascar to formalise his candidacy; General Randrianafidiosa, another strong rival, who refused to pay Ariary 25,000,000 to run; and Didier Ratsiraka himself, because his residence in France made him unable to submit his candidacy in person (as the law requires) (EISA, 2007).

An example of Ravalomanana’s abuse of the law was the matter of the allocation of seats right before the 2007 parliamentary election. According to the EISA mission, it was “undertaken without any clear or defined criteria”, not taking into consideration the size of the constituencies, and thus eroding the principle of “one person, one vote”. For instance, while the constituency of Antananarivo II had two seats allocated for a population of about 130,000, the constituency of Mananjary had one seat for a population of over 700,000. This was largely perceived as a strategy by the president to strengthen his political heartland and weaken the regions where the opposition was traditionally stronger. Facing an increasingly uneven playing field, some opposition parties decided to join forces in specific constituencies where they had no advantage in running alone, but TIM still ended up winning 105 of the 127 possible seats (EISA, 2008).

These are just illustrations of how the playing field is constantly reshaped and adjusted in the interests of the party/president of the day. The tactics described above are so prevalent that those in opposition behave in the same way when they get into power. In fact, parties in Madagascar behave not as agents of democracy but as agents of neopatrimonialism (Marcus & Ratsimbaharison, 2005), and resort to other mechanisms - access to law and media (public and private) - to skew competition in their favour. Paradoxically, however, this analysis also demonstrates the limits of these tactics in Madagascar’s politics. The extreme volatility and turnover in elections, and the sudden rise and fall of political parties and leaders, suggest that these strategies are not as effective as expected and fail to reduce electoral uncertainty. At best parties and presidents only achieve short-term gains.

Conclusion

This article’s main goal was to understand why the Madagascar party system has remained fluid, showing no signs of consolidation since the beginning of the Third Republic. The explanatory model developed here has explored party building strategies during the authoritarian era, and also the extent to which incumbents have successfully skewed the playing field to their advantage.

Regarding authoritarian legacies, we noted that parties emerged from above on the basis of elites’ calculations to enter the political contest. Parties generally lacked strong organisation and social anchors, and represented loose interests and vague ideologies. In this context, neopatrimonial leadership in combination with ethnic identity and personalism, have been essential assets for party development since independence and beyond the Third Republic. Indeed, party organisations that emerged in Madagascar during the last two decades have traits that can be traced back to the First and Second Republics: centralised leadership, thin organisation, lack of core ideologies and prevalence of ethnic, personal and clientelistic appeals. Precisely because they relied more on material sources of support - that is on their ability to reward their supporters - rather than on more symbolic and ideological foundations, these parties have proven more vulnerable and less durable.

Regarding the playing field, observing key electoral moments allowed us to reveal the ways in which the rules of the game are in constant flux. Incumbent parties take advantage of state resources to further expand their neopatrimonial networks but also rely on the wealth, prestige and visibility of their leaders; but so do opposition parties that successfully challenge incumbency. Overall, there are no substantive differences in party behaviour: those in opposition eventually mimic the same actions when they get into power.

The analysis also highlighted important paradoxes that deserve further discussion. On the one hand, the attempts of presidents/parties to change the rules of the game have failed to guarantee their survival over time. While elsewhere in Africa, skewing the playing field is a strategy that incumbent autocrats have used to maintain their position, in Madagascar, parties and candidates do not stay long in power; on the contrary, there is a high electoral turnover. On the other hand, by showing the limits of these tactics, this study also points to an endemic instability built on the origins of political parties, and the weakness of the state.

But taking this discussion further, there seems to be a pattern in the rise and fall of parties and candidates in Madagascar that might help explain why strategies of creating uneven playing fields has not contributed to the consolidation of a stable authoritarian leadership but rather has resulted in a high frequency of changes of power. Despite successful attempts by Ratsiraka and Ravalomanana to skew the playing field, their opponents (Ravalomanana and Rajoelina, respectively) had access to resources that allowed them to overcome imbalances: immense personal wealth that compensated for the lack of access to state resources, business enterprises in television and radio to counter the uneven access to the media, and popular support that enabled them to contest unequal access to the law. While the playing field was indeed rigged enough to neutralise the remaining forces of the opposition, this combination of factors allowed both Ravalomanana and Rajoelina to compete on the same level as the incumbents. The only exception seems to have been in the transfer of power from Zafy to Ratsiraka, in 1996. However, given that Zafy was peacefully removed from office through an impeachment process, we can make a case for there having been a not-so uneven playing field. The electoral contest between Rajaonarimampianina and Robinson does not count as an exception, since Ravalomanana and Rajoelina were not allowed to contend; had they been allowed, the other two candidates would not have stood a chance, given the conditions of the playing field.

Overall, this study contributes to our understanding of the functioning competitive authoritarianism in contexts of weak parties, weak state structures and ineffective coercive structures, which also seem to characterise other countries on the continent, such as Malawi, Kenya, Zambia and Comoros. Further research should continue to explore how the various forms of authoritarian legacy impact the contemporary dynamics of party system development, and how incumbent and opposition parties interact in a competitive authoritarian regime. In particular, it is important to examine the strategies used by both sides and why and when tactics to skew the playing field succeed or fail.