In the last two decades, African democracies have made remarkable progress in expanding suffrage and opening political space. Democratic transitions and economic development have enabled far-reaching radio and television network expansion. The majority of African respondents in the 2018 Afrobarometer surveys report that they receive the majority of their news via the radio. Additionally, the proportion of those who receive their news from the television has also dramatically increased from just 21% in 1999 to 38.5% who said they received news from TV daily. There is a general sense that increased access to digital information technology is good for democracy in Africa and other developing regions (Bailard, 2012; Bailard & Livingston, 2014).

However, even as access to information has become more accessible, incumbent governments continue to wield power over media and use that power to restrict citizen access to information when it suits them. Thus, more and more citizens are relying on the internet for more diverse independent news sources. The growth of cellphone networks and fiber optics across the continent has lowered the cost of receiving and sending information. In the last decade, the proportion of Africans in the Afrobarometer surveys who reported that they receive news from the internet rose from 2.6% in 2008 to 14.5% in 2014. Improved fiber optic-networks have also made the internet easily accessible on mobile phones. Over 70% of African respondents in the 2015 Afrobarometer surveys reported that they use their mobile every day. In 2017, Facebook reported that it had reached 170 million users in Africa (Shapshak, 2017). There is no publicly available official data from social media companies or governments in African for other social media platforms. However, conservative estimates from websites that track internet usage such as internetworldstats.com suggest that at least 11 million African users are active on Twitter, LinkedIn, and WhatsApp and that more than 2.9 million videos are viewed from YouTube each month (Internet World Stats, 2017). African citizens are using online platforms to connect with friends and family, as well as to discuss politics. With the goal of contributing to the growing literature on the impact of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) on African politics, this paper asks the following questions: 1) how are people getting involved in politics through social media? 2) how are they trying to push democracy? And 3) what have been the responses of the authoritarian government?

This paper begins with a theoretical look at the literature on digital engagement and goes into a brief history of social media engagement in various African contexts. The paper then goes into an in-depth discussion of the methodology used for this study and a discussion of the findings.

Theorizing the digital citizen

Since the success of the Arab Spring revolutions in the Middle East and North Africa, there has been growing expectation that digital Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), particularly social media platforms like Facebook, can foster political mobilization thereby contributing positively to democratic growth (Breuer & Groshek, 2014). Scholars in support of ICTs as a “liberation technology” argue that mobile phones and internet access offer citizens low cost, secure, and decentralized pathways to engage with politics (Castells, 2011; Mustvairo & Sirks, 2011). It is further argued that these technologies shield citizens, particularly those in authoritarian regimes, where communication is heavily monitored and regulated from the prying eyes of the state. Theoretically, we would also expect that it should be easier for politicians to reach previously excluded people in politics (Bode, 2012; Conroy et al., 2012; Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2012; Vitak et al., 2011; Steenkamp and Hyde-Clarke, 2014). Lee (2012) found that Chinese citizens in the privacy of their homes and on their phones and computers can discuss grievances, and this engagement can translate into real political action by joining protests. In the Zimbabwean case, we have seen some increase in the degree to which citizens are engaging in politics.

For young people with limited financial resources, social media is a low-cost way to engage with the political conversation. Unlike traditional text messaging systems that charge users per message sent in most countries, users buy monthly bundles for WhatsApp or Facebook that allow them unlimited usage for costs as low as US$1/month. In countries like Zimbabwe were citizen political engagement is heavily policed by the state, engaging on social media away from the watchful eye of the state, allows citizens to engage with politics with a sense of security. WhatsApp claims that their messages are encrypted, and users also use false names on public platforms likes Facebook and Twitter.

In recent years, Africans, especially in the sub-Saharan region, have embraced social media as a tool to engage with politics. In 2015, the #feesmustfall campaign, the demand by South African University students for more affordable tuition, attracted significant regional and global attention, forcing the South African government to freeze proposed tuition increments (AfricaIsACountry, 2015; Booysen, 2016). The success of #feesmustfall ignited citizen campaigns, often referred to as the hashtag movements all across the continent. In 2016 alone, there were at least 15 high profile social media campaigns. The campaigns ranged from those demanding significant changes in policy such as #feesmustfall, a campaign demanding that university lower fees or those seeking to redress social inequalities by calling for the removal of historical monuments such as #rhodesmustfall and #ghandimustfall to those with minimal asks such those demanding that the cost of internet bundles be reduced in Zimbabwe and South Africa #datamustfall. Among the high-stake campaigns was the #rhodesmustfall, which demanded the removal of the statue of British colonialist Cecil Rhodes at the University of Capetown (UCT) in South Africa (Chaudhuri, 2016). At the University of Ghana, a #ghandimustfall petition on charge.org calling for the removal of Mahatma Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s statue from campus garnered nearly 2,000 signatures (Aberqu, 2016). Sponsors of the petition argued that although Gandhi is globally renowned for his fight against racism in India, he was, in fact, very racist towards black Africans, and, thus, his troubled legacy in Africa was sufficient to remove his statue form public spaces (Taylor, 2016). Social media campaigns are often led by youth and those in the middle class.

In Zimbabwe, a little-known Pastor, Evan Mawarire, shook Zimbabwean politics when his homemade video bemoaning the lost promises of the nation’s liberation struggle went viral attracting nearly a million views in Zimbabwe. Pastor Evan Mawarire’s #thisflag campaign in an unprecedented move revived urban activism, which had been thwarted by citizen fatigue and state repression. For 25 days starting on April 18, 2016, Evan Mawarire posted daily videos on various socio-economic topics. In July 2016, he joined with other activist groups, including the youth-led more radical #tajamuka “we are fed up” and called for a national shutdown. Since then, Mawarire has been arrested and accused by the state of being an informant. At the peak of his engagement, citizens widely shared and discussed the contents of his videos on social media and Facebook groups. Mawarire’s online videos had an impact factor well into the millions as people from all over the world relied on his message for their take on the ongoing situation in Zimbabwe. Using #AfricaDecides, Africans followed election events across the continent. Many Africans commented online that this was their first time publicly showing interest in elections other than their own. Africans and the world followed with interest the events in the Gambia after former President Jammeh lost the election and then reneged on his televised promises to step down. In the Zimbabwean WhatsApp groups, citizens discussed the Gambian election looking for similarities to their situation. As it became clear that Jammeh would not only leave office but the country as well, Zimbabweans discussed the possibility of organizing community engagement to protect elections. Using social campaigns like #ifafricawasabar started by then 21-year-old pan-Africanist Siyanda Mohitsiwa, Africans used humor to poke fun at their national politics and challenge stereotypes.

In April 2016, the UK-based firm Portland published an extensive report on “how Africa tweets” (Portland Communications, 2016). Their analyses of over 1.6 billion geo-located tweets found that 1 in 10 of the most popular African hashtags in 2015 was related to political issues and politicians, compared to 2 percent of hashtags in the United States and the United Kingdom. In Africa, every tweet or Facebook post has the potential to become political. In January 2017, during his tenure as Vice President, Emmerson Mnangagwa received a coffee mug engraved “boss” as a gift. A picture of the mug was circulated on social media and eventually used against Mr. Mnangagwa in ZANU PF’s factional wars (News24, 2017). The rise of online activists like Evan Mawarire brought to the forefront a question that has been raised since the 2012 Arab Spring. Can the internet revolutionize African politics? In this paper, I argue that the internet can revolutionize politics but not in the way of the Arab Spring. The revolution will not be broad, sweeping, as we witnessed in North Africa. Instead, while the campaigns will be sporadic and often small in size, they will also make a substantial political impact. The Zimbabwean government and opponents of Evan Mawarire mocked #thisflag and other citizen movements, calling them “popcorn movements” (Frey, 2017). Their strength in changing politics will come in small bursts and tiny “revolutionary” acts that have already begun to open up politics.

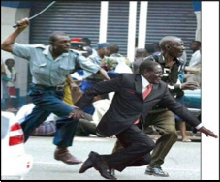

An analysis of the impact of social media on African politics that only focuses on quantifiable wins may miss the small but powerful impact of citizens raising their voices. Following the first shutdown, Zimbabwe’s First Lady addressed the ZANU PF women’s league. In an impassioned speech targeting Pastor Evan Mawarire, the former First Lady Dr. Amai Grace Mugabe decried the millions of dollars that her business lost over the two-day shutdown. Mawarire was arrested a week after the first shutdown and a day before the scheduled second shutdown. His arrest prompted several thousand citizens to show up at the courthouse in protest of what many citizens considered an unjust arrest. When I arrived at the courthouse at 10 am that morning there were less than 50 people, by the time he was released shortly after 7 pm there were an estimated 5,000 citizens peacefully protesting his arrest.

Methodology: Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and WhatsApp as fieldwork

According to Facebook’s official statistics released in May 2017, users send 31.25 million messages and view at least 2.77 million videos per minute (Facebook, 2017). On Twitter, users send out over 300,000 tweets per minute, over 48,000 Instagram pictures are shared per minute, and at least 300 hours of video are uploaded every minute on YouTube (Lowe, 2016). These numbers change by the minute as new users join the social media sphere. Users can also choose to make private or public their posts on these platforms; this can make a systematic study of behavior online tricky but not impossible.

Given the difficulty of collecting data on Facebook and WhatsApp platforms, which are private and encrypted, I decided to use ethnographic participant observation methods to study the breadth of political conversation among Zimbabweans between June 2016 and June 2017. In this particular case, the researcher joined the group as a member (participant) but did not make any contributions to the conversations, thus maintaining an ethnographic distance and allowing for participant observation. The use of digital ethnographic methods to study communication and citizen behavior on the internet is becoming more standard (Murthy, 2008; Mutsvairo & Sirks, 2015). However, scholars continue to debate the best strategies to use and the ethics of studying behavior on the internet (Wilson et al., 2012). On the one hand, scholars see tension by referring to studies that are not conducted in the physical field in which the researcher shares space with subjects as ethnographic. The full debate on ethnographic complexity is beyond the scope of this paper, but it suffices to say that this study meets the basic goals of ethnography “attendance and observation” (Wittel, 2000). By immersing myself in Zimbabwe’s online community, this study also meets the standards set by Clifford Geetz for thick description, which can be achieved if a researcher spends extended time engaged with the community under study.

To study the impact of social media in Zimbabwean politics, the initial methodology included large scale analyses of citizen political engagement on Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp. Scholars interested in explaining large scale citizen engagement on social tend to use a variety of software tools that harvest tweets from the web for analysis (Zimmer & Proferes, 2014). Quantitative analysis of digital media reveals larger patterns of behavior that can be generalized beyond one subgroup (Marwick, 2014). In the Zimbabwean context, the data collected using NodLex software revealed that the majority of tweets are by a few individuals, many of whom are either middle class elites or members of the diaspora. These two groups play an important role in Zimbabwean politics, but the unrepresentative nature of data collected from Twitter made it impossible to conduct any meaningful and generalizable quantitative analysis. Another important revelation was that some of the popular Tweeter users are unverifiable. This is to say there are no known individuals behind the Twitter account. In authoritarian regimes, it is not surprising that individuals might to choose to use pseudo names to protect themselves against government policing of their public thoughts. The presence of fake accounts complicates the ability to do meaningful ethnographic work. With this in mind I decided to focus this paper on data collected from Facebook and WhatsApp groups.

On Facebook and WhatsApp, the majority of conversation occurs in private or public social network groups. Facebook groups are communities created with the Facebook social networking site that are based on real-life interests or groups that declare support/affiliation with a cause. Creators of the Facebook groups can choose to make group membership open meaning that anyone with a Facebook account can join the group or membership can be granted once approved by a group administrator. More and more groups now require approval to join. Therefore, it is impossible to use software tools to collect data. An additional disadvantage of using software tools to pull data is that much of the communication does not happen in standard English language and people tend to code switch.

People in Facebook groups tend to find solidarity with a community that shares common interests and in order to fully understand the dynamic of each group, traditional ethnographic methods of participant observation are best. To that end, this researcher joined 50 of the most popular Zimbabwean Facebook pages, groups and WhatsApp groups. A group was deemed popular if it had more than 2,000 members and if in a week a single post attracted over 1,000 comments and likes on any topic. One women’s group has a membership of over 70,000 Zimbabwean women with group members somewhat evenly spread between those residing in Zimbabwe and those in the diaspora. In addition to joining groups, the methodology included analysis of trends on popular pages like zimeye.net, a tabloid/news website with popular social media presence, Voice of America’s Harare Studio Seven, political party pages, and becoming friends with or following popular activists, politicians and social commentators like Pastor Evan Mawarire and iHarare, another social /local gossip and politics page.

On WhatsApp, community groups are private and there is no easy way to find access conversation without invitation from one of the administrators. I contacted active politicians and activists, academics, journalists and friends for permission to join their WhatsApp groups. Groups joined for this research included those that only discuss politics, partisan groups, social activist groups, and family groups. In total, I actively followed political conversation in 25 online community groups between June 2016 and June 2017.

To supplement observational data, I conducted 20 interviews with randomly selected members of WhatsApp and Facebook groups. Respondents were asked open-ended questions on their level of political interest and engagement, their main sources of news and what if any political actions they would be willing to take. In 2016, group members were also asked if they had participated in specific citizen led political rallies and stayaways. Where possible, respondents were asked to share pictures as evidence of their participation in the different political activities. Citizens were more likely to stayaway than to attend a rally. However, more citizens attended rallies in 2016 than in the past based on self-reports and data from the rallies.

Can the revolution be tweeted? To answer this question, a final part of the methodology was to show a connection between citizen demands via social media and government response. Government response ranges from acknowledgement of a problem by a minister to a change in policy aligned with the demands of citizens. Laws often take a long time to become final but in the majority of African countries where the executive is very powerful a change in policy can be immediate. The government can also respond negatively by shutting down a campaign, ignoring demands or adding further restrictions.

Social media politics in an authoritarian regime: increased access to information when the media is the enemy

African presidents are rarely seen or heard from. The image of African leaders is well choreographed. Under Section 33 of Zimbabwe’s Criminal Codification and Reform Act, a person could be jailed for up to a year or fined $100 (£64) for insulting the president’s office. The law states:

Any person who makes any abusive, indecent or obscene statement about or concerning the President or an acting President, whether in respect of the President personally or the President’s office shall be guilty of undermining the authority of or insulting the President and liable to a fine not exceeding level six or imprisonment for a period not exceeding one year or both. (Criminal Law Act, 33, (2), (b))1

Although the law was deemed unconstitutional in 2013, many Zimbabweans have since been arrested or forced into exile under this law for offenses that range from writing a song (Zimbabwe, 2013), that is deemed offensive by the state, journalists writing about the 92-year-old president’s fragile health (CPJ, 2017) or citizens distributing “subversive” material detailing cases of corruption committed by government officials (Deutsche Welle, n.d.). Many opposition politicians have been disappeared for offenses as small as using the president’s toilet (Smith, 2011). In all these cases charges were eventually dropped but trial process is used to install fear in other citizens.

In Zimbabwe, as in most African governments, officials are mandated to hang the president’s portrait in their offices and public spaces (BBC Talking Point, 2000). While private businesses are not required by law to do this it is commonly understood that not hanging the portrait can be interpreted as a sign of defiance. In 2012, Oliver Mtukudzi’s lighting technicians were arrested “inciting political sentiment”2 after he had allegedly directed spotlights onto portraits of President Mugabe during the song Wasakara (you’re now wasted), the title track of Mtukudzi’s Bvuma/Tolerance album. The president’s spokesperson Mr. George Charamba in a typical state response said what the technician did was an abuse of the office of the president.

In Zimbabwe citizens understand that there is freedom before speech, but human rights and freedom are not guaranteed after speech. Under the 2002 Public Order and Security Act (POSA) public gatherings require a seven-day prior notice and get approval from the police, failure to get either can result in both criminal and civil charges against the organizers (Thornycroft, 2001). As such, citizens have often had to be too careful what they say about politics. When asked if they discuss politics with friends and family, Zimbabweans have consistently said that they are afraid to do so.

Access to internet has opened political communication, the ability of citizens to circulate media about the president, pictures or jokes has demystified political leaders. From the safety of their mobile phones, Zimbabweans have been able to share jokes, comments and thoughts on politics without fear of retribution. On February 5, 2015 President Mugabe publicly fell. Pictures of the statesman falling garnered global attention and memes by Zimbabweans on social media went viral.

Zimbabweans used the memes to mock the state media’s iron clad control of the news narrative. It was not just that the president fell, but for the first time in a long-time citizens could comment without fear of retribution because social media provided them a veil of anonymity. The meme’s also humanized Robert Mugabe. Since independence Robert Mugabe has been viewed as this towering figure that cannot be challenged and cannot be mocked.

Zimbabwe’s television and radio spaces are tightly controlled by the ruling party. The local radio channels and the one TV channel is run by the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Cooperation (ZBC) which, like the state-run newspaper The Herald only broadcast preapproved information. According to a report by the independent Think Tank Kubatana, during the 2008 election ZBC devoted 210 hours to coverage on ZANU PF against the 16 hours they devoted to the other political parties (MMPZ, 2008). This obvious partisanship behavior by ZBC is unconstitutional. In 2000, the Supreme Court of Zimbabwe declared the monopoly of the state-owned Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation unconstitutional, and yet the government has still not awarded an operating license to any prospective private broadcaster. Using the internet and social media platforms like Facebook, YouTube and Instagram independent broadcasters have been able to provide political commentary on important topics which the state media refuses to report on. Comedy shows that emulate American late-night political comedies have mushroomed in the last few years.

One popular comedian is Comrade Fatso, a young white Zimbabwean who runs Magamba TV, one of the most popular apolitical satire online channels. It was co-founded in 2008 by Farai Monro “Comrade Fatso” and Tawanda “Outspoken” Makawa, an extension to their now banned music group. Magamba TV is described as “Zimbabwe’s leading producer of cutting edge, political satire and comedy shows” on their Facebook and YouTube pages which have 30,905 and over 3,000 subscriber’s reviewers respectively. Since independence the population of white Zimbabweans in broadcasting has declined. In fact, Farai is one of very few white Zimbabweans openly commenting on politics. Social media provides access to marginalized groups who cannot openly participate in Zimbabwean politics. Their most popular segment, from December 2016, which they mocked the government’s proposal to introduce a parallel currency to the American dollar, has been viewed over 50,000 times on Facebook and YouTube and shared nearly as many times on WhatsApp.

BusStopTV is a two-woman popular comedy channel that addresses popular social and political issues. Their style is influenced by the very popular Ugandan comedian Anne Kansiime, who also addresses political issues like corruption using satire. BusStopTV has 15,000 subscriptions on YouTube and over 80,000 likes on Facebook. Their following has grown steadily. Their most popular segments are ones that mocked local celebrities, including religious leaders. However, in the last year, segments that mock politicians have also grown in popularity. Following Grace Mugabe’s diplomatic scandal in South Africa wherein the First Lady allegedly beat up a young woman who was in the company of her children using an extension code and the Vice President Mnangagwa’s ice-cream poisoning, they released their most popular segment to date, Women’s Month, which was viewed 90,000 times within four days of being posted on Facebook. However, political satire is not without cost. The first challenge for the young activists is the exorbitant cost of producing film.

Zimbabwe’s ruling party perceives the media, especially independent media, as a political rival, not as an independent arm of democratic governance. The executive branch of the government tightly controls the state media. Zimbabwe’s 2013 Constitution protects the right to “freedom of expression which includes the freedom to hold opinions and to receive and or communicate ideas without interference” (Section 60, 1-4), but ZANU PF constantly reminds citizens that while there is freedom before speech, freedom after speech is not guaranteed. In Zimbabwe, insulting the office or person of the president and his subordinates is a criminal offense. Journalists are often physically and verbally abused and in some extreme cases, those who publish information considered treasonous are forced into exile, tortured or killed. During the 2016 protests, the government arrested at least 31 journalists (Human Rights Watch, 2017).

Former President Robert Mugabe and the First Lady would often publicly chide journalists, including those from state media, if they feel that the media has slighted them. At a ZANU PF rally in July 2017, the First Lady Dr. Grace Mugabe, publicly chided the president’s spokesperson George Charamba for going off script and specifically for not using his platform to write positive reports on her philanthropic work. She also expressed anger over George Charamba, for using the state-controlled Herald newspaper as a platform for attacking some ZANU PF activists like ministers Moyo and Kasukuwere among others (ZemTV News, 2017). In earlier speeches at rallies in 2017, the President and First Lady also publicly called on ZANU PF youth to “take the war” to social media and deal with those trying to sellout the country using social media.

Social media politics: four examples

Baba Jukwa the whistleblower

In the period leading up to the 2013 elections, Zimbabwean politics was shaken by the rise of an online whistleblower by the pseudo name Baba Jukwa. Baba Jukwa described himself on his Facebook page as a “concerned father, fighting nepotism and directly linking community and their leaders” (Muzamindo, 2015). Baba Jukwa’s profile picture was that of an old non-threatening wise grandfather holding a cane. Baba Jukwa was assumed to be a disgruntled ZANU PF insider, possibly a member of the intelligence community. However, in 2014, Edmond Kudzayi, editor-in-chief of the state-controlled Sunday Mail, together with his brother Phillip Kudzayi and two others were arrested and accused of administering the Baba Jukwa Facebook page. Daily for a period of about eight months Baba Jukwa would leak information on classified government events, he would predict government responses to his leaks and in some cases, he would leak photos and other personal information of those involved in a tabloid-like manner.

Baba Jukwa was coined the Julian Assange of Zimbabwe. Baba Jukwa predicted a number of high-profile events that turned out to be true. In fact, on June 13th, 2015 Baba Jukwa predicted the arrest of the Kudzayi brothers and two others accused of administering the page. This was unprecedented in Zimbabwean politics where the state has always closely guarded information. Information is parceled out in bits and pieces such that citizens are never fully knowledgeable about the state of national affairs. Until the rise of online news outlets, the major news sources were heavily controlled by the state. Independent media publishing houses have been victims of state violence. The leading national newspaper, Herald, functions like a mouth-piece for the ruling party ZANU PF. More often than not, Herald coverage is only free and fair to the extent that the paper is pushing an agenda supported by one of ZANU PF’s factions. Television broadcast is also heavily controlled by the state.

Whereas ZANU PF rallies are broadcast live on television, opposition rallies do not get any coverage. Baba Jukwa was welcomed by citizens hungering for an inside look into the government. Baba Jukwa also exposed the state’s weaknesses in their ability to control information in the digital age. The Zimbabwean government is repressive and has powerful tools to silence dissenters, it was expected that they would soon discover Baba Jukwa and silence him. However, during his very brief existence Baba Jukwa exposed the weakness in ZANU PF’s control over information. Baba Jukwa’s page has been viewed more than a few million times. In June 2013, a month before the 2013 election, I recorded that it had just over 300,000 followers. By the time Baba Jukwa was apprehended the page’s following had increased to over 480,000. In contrast, social media following for pages dedicated to President Robert Mugabe and MDC President Morgan Tsvangirai had about 100,000 followers each in 2013 (Regan-Sachs, 2013).

Baba Jukwa’s following was very diverse, it cut across different societal cleavages: ethnicity, race, tribe, and class. Access to Baba Jukwa was cheaper than buying a newspaper3, in 2013 one could buy Facebook internet bundles for $1/month. In 2013, a few months before the July election I conducted focus groups in Harare with potential voters. When I asked, “Where do you get your news?,” the majority, over fifty percent of those who responded said they checked Baba Jukwa’s Facebook page first thing in the morning. In the absence of a robust independent media, Baba Jukwa was the anecdote to ZANU PF’s Herald propaganda. A month before the election Baba Jukwa revealed that the life of a young member of Parliament, Edward Chindori Chininga, was at risk and that the government thought to replace him with a less threatening figure. Chininga, who had released a damning report on corruption, was found dead nine days after Baba Jukwa released this scoop (NewsDay, 2013). In Zimbabwe, political opponents of the regime are often disappearing or die under mysterious circumstances.

Baba Jukwa was also appealing to readers because most of what he reported was gossip and scandalous. As much as Baba Jukwa revealed important stories he also fed voters sensational stories about the personal lives of those in government. In a country where information is heavily policed even the most mundane gossip becomes worthy news and citizens held on to that. The most popular “news” sources online are those that publish (stats) tabloid news. Baba Jukwa did not revolutionize Zimbabwean politics in the sense that the news that he provided increased voter turnout. Instead he fed citizen interest in the political process. Baba Jukwa’s more direct efforts to get citizens to register to vote do not appear to have had much impact on voters. Using his mantra “Asijiki” we will not be tired, he also used his message to get people to turn out and vote but this message drew little interest from voters who were more drawn to the scandals. After the 2013 election, most voters expressed anger towards Baba Jukwa blaming him for ZANU PF’s win. Citizens took to Facebook and Twitter to express their anger; many argued that Baba Jukwa had been used by ZANU PF to divert voters from the real issues. While it is doubtful that Baba Jukwa was intended to benefit ZANU PF at the election, one of the lessons that can be drawn from this is that online engagement has broad implications including unintended consequences. That said, there is no doubt that Baba Jukwa liberated the control of information and demystified political leaders. Baba Jukwa exposed citizens to the political power of social media. While Baba Jukwa’s popularity has died down, the Baba Jukwa 2018 election page only has 17,000 followers and most of his posts receive less than 15 comments on any day, the political activity of Zimbabweans on social media has gone up.

Gukurahundi as a current topic

Gukurahundi (wash away the dirt) refers to the 1983 mass killing of citizens in Matabeleland at the instruction of the newly elected Prime Minister, Robert Mugabe, and his fifth brigade army. In an interview with Dali Tambo in 2012 President Mugabe referred to the incident as a “moment of madness” (Tambo, 2013). Until recently, the majority of Zimbabweans did not publicly discuss Gukurahundi because history and school text books have been carefully curated to exclude any mention of Gukurahundi along with other events that do not fit the government’s preferred historical narrative. In 2012, artists created a visual portrayal of Gukurahundi that went viral and created an opening for citizen dialogue on the issue. The government retaliated against the artists whose work was featured in the exhibit (Dugger, 2011). The government was forced to push back on allegations that Vice President Mr. Mnangagwa played an active role in the massacres.

Since announcing her run for President, following her expulsion from ZANU PF and the office of the Vice Presidency, Joice Mujuru has had trouble answering questions on her involvement in Gukurahundi on the campaign trail (Muzulu, 2017). Ten years ago, most people would not have expected that Gukurahundi would become an important campaign issue. It is unlikely that the Gukurahundi cloud will be damaging to any of the ruling party contenders in the immediate future, but it cleared that Zimbabwean citizens are increasingly concerned about the issue. In May 2017, when bones from a Gukurahundi dumping site were published by an online news website, the publication received a lot criticism and backlash from citizens forcing them to retract the story and delete the offending pictures. Building on citizen interest in Gukurahundi, Vice President Mphoko in May 2017 proposed that the government implement a peace and reconciliation program to directly address victims of Gukurahundi and other atrocities. Mr. Mphoko said that there was need for the nation to collectively address the issue to allow victims to move on with their lives.

Operation Murambatsvina

One of the most recent heinous crimes committed by the ZANU PF government was the clean-up exercise conducted in 2005 that left at least 700,000 urban families homeless. The majority of poor vendors affected by operation Murambatsvina lost their sources of livelihood. Interviews with those impacted in Harare and Victoria Falls also showed serious adverse health impact for HIV patients impacted by operation Murambatsvina. Operation Murambatsvina was the ZANU PF’s government first attempt at destroying the homes of citizens hiding behind the need to clean up the city. They did the same in Epworth and other peri-urban areas in 1995 and 1996. As in 2005, earlier efforts were also conducted around election time and each time voters were strategically relocated to bolster support for ZANU PF.

In early 2016, the city of Harare began a new wave of demolitions in the city. Onlookers took videos of the demolitions and circulated them online via WhatsApp, Twitter and Facebook. One video that garnered the most viewership was the demolition of a fully furnished double story home. The public called out the city officials who gave contractors passing grades at each level of building only to rescind their approval years after the buildings had been completed and occupied. The city council was not responsive until the First Lady brought up the videos, which she said she had also received via WhatsApp. Grace Mugabe chided the opposition run city council and demanded that they offer reparations to those affected by the newest wave of demolitions.

However, social media attention does not always result in the positive resolution of social justice issues. In June 2017, picture of families of mostly women and children including a newly born baby who were evicted from land claimed by the First Lady made rounds on social media, but the First Lady chose to ignore public demands for redress. It is unlikely that social media pressure from citizens will force the First Lady to address the situation, but citizen awareness on the issue is an important first step. In the past, atrocities by those in power have not been known to citizens. Some citizens have responded to the situation in Mazowe farms by calling for a boycott of dairy products from the First Family’s farm.

The rise of #thisflag, #tjamuka, Zimbabwe’s 2016 shutdown and impact

In Zimbabwe, hashtag campaigns have been citizen driven, sometimes political parties have joined in to support a cause but by and large the campaigns have been the brainchild of a small group of citizens. In 2016, a little-known Harare Pastor began his 25 day #thisflag campaign to highlight the social and economic problems in Zimbabwe. In the first video shot in a dimly lit office with a small Zimbabwean flag on his desk he expressed concern and frustration that the liberation struggle promises embodied in the colors of the national flag have been realized for the younger generations. He made a pledge to post every day until May 25. Pastor Evan Mawarire’s popularity grew steadily. On social media groups comments and views on his posts grew from less than ten during the first week to a few thousands on Facebook and to real engagement on WhatsApp. His message #thisflag was different because it was not immediately political, he was a pastor unaffiliated with any political party and most people interviewed at the time said they liked listening to him because he was a father. Evan Mawarire was petitioning the government to change things and not calling for an ouster of the government.

In May, interviews on the ground revealed that Mawarire’s message was not nearly as widespread as social media likes and comments suggested, but for the first time in many years someone had unified Zimbabwean political rhetoric. Mawarire’s signature symbol, the Zimbabwean flag draped around the shoulders, became a symbol for a generation disgruntled. In June, the economic crisis was deepening, civil servants had not been paid for months and the general mood around the country was tense. Earlier that year another citizen group #tajamuka had also gained popularity among “ghetto” urban youth. Tajamuka is a Shona word meaning we are upset. Unlike #thisflag which was very middle class in its design, the use of cell phone videos and English to address the public #tajamuka was very active on the ground and unafraid to use physical means to express their message. The #thisflag and #tajamuka messages were used by citizens to call for #shutdowns. The last public strike was in the mid-1990s even the MDC had not been able to convince Zimbabweans to shut down the country. Messages asking people to stay at home were circulated via social media on Facebook and WhatsApp groups. On social media citizens were skeptical about the shutdown because there was no central space to get clarifications or instructions on what to do. The shutdown was solidified when the public transport drivers announced that they would not be operating on the day of the shutdown. There were also threats of violence against those who chose to leave their houses, but such messages were not as widely circulated as the ones appealing to nationalism and the shared dream of a better Zimbabwe.

On July 6, Zimbabwe was indeed shutdown, in both urban and rural areas there was no economic activity. The handful of businesses that did not heed the call to shutdown faced public lash. The following day only the state media reported that the city had been “bustling with energy” and that it was “business as usual”. Two days after the shutdown I asked a diverse group of young students, representing the rich northern, middle income and poor southern neighborhoods to describe the shutdown from their activities and each student recounted that it was very quiet. Civil servants had been informed that missing work due to the shutdown was grounds for dismissal but even then, many of them were unable to make it work because there was no public transport. The stay away was successful not just because of Pastor Evan Mawarire and his social media posts, but because of the joint efforts of multiple citizen groups as well and the efforts on the ground by public transport drivers and conductors.

In the weeks that followed, citizens returned to work and it felt as though the #shutdown had not made a real impact on the government and the economy. However, in a speech marking her election to leader of the women’s league, First Lady Grace Mugabe addressed the shutdown, social media and their impact on the economy. The First Lady directly attacked Pastor Evan Mawarire and called him misguided, she then explained to the crowd that the stay away had cost the country millions of dollars and if this had gone on for a week the impact would have been irreversible. The First Lady went on to explain that her dairy farm had been affected by the losses they incurred from a single day of shutdown.

A week after the first #shutdownzim citizen groups again called for another #shutdown. By all indicators the second shutdown was going to be a flop. The major weakness for hashtag citizens’ groups is their lack of a centralized unit; their goals are not always quantifiable, and, in some cases, citizens might not notice the impact of the campaign. It came as a surprise when word spread via social media that Pastor Evan Mawarire had been arrested. As usual, the details of his arrest were classified, even though the Constitution demands that one should have their arrest details read to them on the day of the arrest. The following day social media was inundated with mixed messages about the Pastor Evan Mawarire’s court appearance.

In Zimbabwe, government spaces are sacred and feared. When one drives past the State House/Presidential Residency they are expected to keep a wide distance and look away from the building. Making eye contact with the guards could be grounds for arrest or being shot at. The Court House never used to be barricaded, this changed after the Mawarire case, but citizens where not expected to walk too close to the high court unless they had evidence of business on the premises. When #thisflag first announced on social media that instead of the shutdown they were now calling on people to show up at the courthouse in solidarity with Pastor Evan, their message was met with skepticism. I arrived at the courthouse 9 am, at that time there was just a handful of people. I attended a workshop in the CBD, which was most certainly bustling with energy in direct contrast to the previous weeks’ stay away environment. When we returned to the courthouse at 2 pm the crowd had increased significantly. Although there was no formal crowd count, unofficial estimates suggest that at least 2,000 citizens showed up at the courthouse. I conducted 30 official interviews with people who had travelled from different parts of Harare; two in particular had walked at least five kilometers in the wintertime to show their support.

Government response

African governments have not been very receptive to the rise of social media. Governments in countries where citizen protests grown out of social media movements have tightened their repressive laws or created new laws to curb social media access. In 2016, AccessNow, an organization dedicated to fighting internet shutdowns reported that African countries accounted for 11 out of the 56 global shutdowns. This was an increase of over 50% from 2015 (Ngwa, 2017). The most severe shutdowns were experienced in Ethiopia and Cameroon. In both countries’ governments shut down the internet for extended periods of time after intense demonstrations that challenged the government’s hold on power. Cameroon’s shutdown lasted 93 days in English-speaking regions of the country. It followed weeks of protests from lawyers, teachers and other residents in those areas who have been agitating for better treatment from the French-speaking government, which they say has long marginalized their communities. A Brookings Institute report estimated that the internet shutdowns in 2016 alone cost countries an estimated $2.4 billion. Beyond financial cost the shutdowns disrupted business, travel and in extreme cases examination periods for students were delayed. In response to the citizen protests in July 2016, and internet campaigns that followed, the government of Zimbabwe drew up internet restriction bills similar to those in China. Minister of Information, Communication and Technology, Supa Mandiwanzira, tried to calm public fears by explaining that the restrictions were to curb social media bullying. The Zimbabwean government, like their counterparts in Cameroon, Ethiopia and across the continent, has argued that these restrictions are part of national security.

While a very authoritarian executive runs Zimbabwe, the judicial and legislative branches of government have remained somewhat autonomous and strong. Therefore, the ruling party will circumvent the legal law-making process to push forward their agenda outside the traditional platforms. The government initially hiked the cost of data/internet bundles as a quick strategy to discourage people from sharing political information online. The cost of going online has always been a lot more expensive in Zimbabwe comparatively. In 2015, USD$1 would buy between 10 megabytes and 17 megabytes between the three providers, Econet (10MB), Netone (17MB), Telecel (9.5MB). The cheapest provider, NetOne, is government controlled and has poor service. The more affordable and privately-owned telecommunications company, Telecel, was forced into a government by out in 2016 (The Financial Gazette, November 29, 2016). The more popular and very expensive Econet is owned by exiled Strive Masiyiwa, a successful tech mogul. Masiyiwa has managed to do well in every other country except his native Zimbabwe because of the government laws that are targeted at keeping him out of business and also physically out of the country. In response to data hikes citizens began the #datamustfall campaign which resulted in the slashing of data fees, but the overall price remains high for the average person earning less than USD$100 per month.

In Zimbabwe, the more successful social media campaigns have been those with a direct ask and ones that do not directly challenge the government’s authority. Efforts to block the first amendment to the Constitution fell on deaf ears. ZANU PF parliamentarians voted with the president. One very active independent candidate who won his seat with support from the opposition, which had actively opposed the first amendment, voted with ZANU PF and used his Twitter celebrity status to mock those who disagreed with his vote.

The emperor is not asleep

Although active social media users tend to be opposed to the ruling party, ruling parties are also engaging with social media. In November 2016, officials approached this researcher from the ZANU PF youth league that was interested in learning more about social media and politics. The league also disclosed that the ruling party was actively recruiting young people with an interest and expertise in social media. ZANU PF’s web presence has grown and surpassed activities by all other parties, including the leading opposition, Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). The main ZANU PF in Zimbabwe has more than five active Facebook pages dedicated to sharing party news and live streaming events. Their live stream events have grown in popularity because while ZANU PF is not popular, citizens are still interested in what happens at the rallies and often ZANU PF is the only party providing live stream. ZANU PF-UK chapter has a strong Twitter presence, they use their presence to mock the opposition and explain ZANU PF policies. In contrast, the MDC has virtually no presence on Facebook and very weak activity on Twitter.

Former President Robert Mugabe and First Lady Grace Mugabe regularly addressed the need for youth in their party to join social media and fight against “detractors of the revolution” using social media. One of the very few Twitter verified Zimbabwean users is Minister of Higher Education Jonathan Moyo, also regarded as the brain behind many of ZANU PF’s most restrictive policies. Moyo is one of the few politicians who constantly engage with citizens. Moyo has developed a strong love and hate relationship with users. Until recently he was the only official engaging directly with citizens. On Jonathan Moyo’s birthday citizens agreed to have a political ceasefire and encouraged each other to only send him well wishes and refrain from political arguments. However, even Jonathan Moyo’s social media is not completely free from party control. He has refused to attend live debates or any events where questions are not delivered in advance and agreed upon. Since his inauguration, President Mnangagwa has also taken up an active role on social media where he offers regular updates of his trips and answers citizen questions.

Conclusion

The full impact of social media on African politics, in particular Zimbabwe, will continue to evolve. Among Zimbabweans, social media has increased citizen discussion of politics beyond traditional networks. Facebook and WhatsApp groups allow citizens to expand their friend and network groups in pretty significant ways. This engagement does not always result in physical participation in rallies or protests in part because the state continues to respond with brutality against protesting citizens thus creating a lot of fear. During the 2018 election, there was a lot of online discussion about the elections but the electoral turnout was not that much higher from previous elections. One possibility is that those already planning to vote are also engaging in online discussions about politics whereas those abstaining from voting are not engaging in online discussions.

As it does, it is clear that the positives outweigh the negative. However, African citizens must be wary of internet dangers such as fake news which tend to spread faster than true news and can have real negative impact. In general citizens have become more engaged with their politics and taken ownership of their democracy in ways that would not have been possible without access to social media. Future studies must be conducted on the impact of online engagement on citizen turnout. Anecdotal evidence from elections in Zimbabwe and other African countries suggests that online engagement has not done much to increase voter participation but it is unclear why those engaged online are not turning up to vote.