Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista de Gestão dos Países de Língua Portuguesa

versão impressa ISSN 1645-4464

RGPLP vol.16 no.3 Lisboa dez. 2017

ARTIGOS

Social marketing in Brazil. History, challenges, and an agenda for the future

Marketing social no Brasil. História, desafios e uma agenda para o futuro

Marketing social en Brasil. Historia, desafíos y una agenda para el futuro

José Mazzon* e Hamilton Carvalho**

* PhD in Administration, Faculty of Economics, Management and Accounting, University of São Paulo and postdoctoral fellow, Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique fellow, Paris. Full Professor, University of São Paulo, Department of Administration, Faculty of Economics, Administration and Accounting, Av. Professor Luciano Gualberto, 908 – Butantã – São Paulo/SP – 05508-010, Brazil. jamazzon@usp.br

** PhD candidate in Business Administration, Faculty of Economics, Administration and Accounting, University of São Paulo. Master in Business Administration, University of São Paulo. State public servant for the Treasury Department, Brazil. Member of the board of International Social Marketing Association. Av. Professor Luciano Gualberto, 908 – Butantã – São Paulo/SP – 05508-010, Brazil. hccarvalho@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Several decades after its birth, social marketing has never become a mainstream tool in the repertoire of social actors designing programs for behavior change in Brazil. Misconceptions about marketing and prejudice against its use in social programs hinder the development of the discipline and its full consideration by upstream social actors. The paper describes a sample of academic studies and key programs that marked the first phase of social marketing in the country. Among the programs, three deserve special attention: the Brazilian Workers’ Food, the fight against HIV and the “Zé Gotinha” vaccination programs. The paper also presents a discussion on barriers and opportunities for social marketing in Brazil, including a three points agenda for accelerating its diffusion.

Key words: Social Marketing; Marketing; Communication

RESUMO

Várias décadas após o seu nascimento, o marketing social nunca se tornou uma ferramenta dominante no repertório de agentes sociais que criam programas de mudança de comportamento no Brasil. Os equívocos sobre o marketing e os preconceitos contra o seu uso em programas sociais impedem o desenvolvimento da disciplina e a sua plena consideração por agentes sociais de topo. O artigo descreve uma mostra de estudos académicos e programas-chave que marcaram a primeira fase do marketing social no país. Entre eles, três merecem atenção especial: o Programa de Alimentação do Trabalhador, a luta contra o HIV e os programas de vacinação «Zé Gotinha». O artigo também apresenta uma discussão sobre barreiras e oportunidades para o marketing social no Brasil, incluindo uma agenda de três pontos para acelerar sua difusão.

Palavras-chave: Marketing Social; Marketing; Comunicação

RESUMEN

Varias décadas después de su nacimiento, el marketing social nunca se convirtió en una herramienta dominante en el repertorio de agentes sociales que crean programas de cambio de comportamiento en Brasil. Los equívocos sobre el marketing y los preconceptos contra su uso en programas sociales impiden el desarrollo de la disciplina y de su plena consideración por los agentes sociales de primer nivel. El artículo describe una muestra de estudios académicos y programas-clave que marcarán la primera fase del marketing social en el país. Entre ellos, tres merecen atención especial: el Programa de Alimentación del Trabajador, la lucha contra el VIH y los programas de vacunación “Zé Gotinha” (poliomelitis). El artículo también presenta una discusión sobre barreras y oportunidades para el marketing social en Brasil, incluyendo una agenda de tres puntos para acelerar su difusión.

Palabras clave: Marketing Social; Marketing; Comunicación

“We are all pedestrians in the city” is a common closing for advertising pieces selling automobiles on TV and radio in Brazil. The ubiquity of that phrase is not a coincidence: since 2010, a law requires that all advertising of products from the automotive industry in any media display an educative message at the end. The Brazilian office for transit norms, following determinations from that law, chooses yearly the set of three to six phrases that will be available for use in advertising (Agência Brasil, 2010).

Perhaps nothing epitomizes more the paradigm governing public initiatives aiming at behavior change in Brazil than this reliance on providing information. Proven conceptual technologies to promote behavior change, such as social marketing and behavioral economics, are typically absent in the repertoire of public executives trying to influence public’s behavior for the benefit of society. Those technologies face strong competition from traditional approaches–education, as in the example above, and the law.

In Brazil, governments, and other social actors, such as media pundits, seem to espouse the belief that people perform their behaviors either out of being ceaselessly informed about its importance or out of punishment prescribed by law (in some rare cases, monetary incentives also integrate the set of legal actions). In other words, when it comes to changing people’s behavior in Brazil, the homo economicus paradigm still is the way to go. In this paradigm, people are assumed to be cold decision makers, always weighing costs and benefits before acting. Moreover, they are assumed to always process the available information and acting whenever it shows a favorable outcome from the proposed course of action (Carvalho and Mazzon, 2013). When people do not perform the expected behavior, the cause, according to the paradigm, is insufficiency of information, weak penalties or incentives, or, worse (as this seems a hidden assumption), laziness or self-sabotage.

Thus, education or informative campaigns are the staple choice of public executives in Brazil, creating a surge of awareness campaigns. The so-called awareness fever is well known among social marketers (Bornkessel, 2010). The term refers both to a strong inflation of “awareness days” throughout the world and to a complacent attitude in the design of social programs, leading to the provision of information to segments of the public with the goal (and hope) of changing their behavior. However, this throw-food-at-the-pigeons’ paradigm, as we call it, is a very limited approach to behavior change. It is limited because information can only go so far to change people’s behavior. Considering the example of traffic accidents that motivated the law cited in the beginning of the paper, the current rate of deaths per 100,000 inhabitants is 25% higher than in the decade of 1980 (Gomes, 2014). Clearly, Brazil has been losing the battle against drunk driving and other risky behaviors that claim the lives of so many people in the country. Nonetheless, Brazilian drivers are constantly bombarded with information about “correct” behaviors on road, as the example in Figure 1 illustrates (an alert to turn on the lights on roads).

Based on its successful history in changing behaviors in critical societal contexts throughout the world (Lee and Kotler, 2015), social marketing has an enormous potential to improve markedly the lives of Brazilians. Considering that the discipline was founded in 1971 (Kotler and Zaltman, 1971), its absence in the repertoire of Brazilian public executives calls for an explanation. Why does that happen?

This paper proposes an answer to that question. We first present a general panorama of social marketing in Brazil, in academic and professional settings. We describe the main programs that resembled a social marketing approach or symbolized a clever use of marketing to tackle social problems in the country. In the final part of the paper, we also propose a three points agenda to accelerate the diffusion of social marketing among key social actors.

To present the panorama that follows, we conducted personal interviews with a sample of the few academics and professionals involved with social marketing in Brazil. To have a better perspective, we also interviewed social marketers from other Latin America countries, identified after a query in the social marketing email listserv in 2014, then under the management of Georgetown University. We also searched academic databases looking for Brazilian papers, masters’ dissertations and PhD thesis that utilized social marketing as a guiding lens. While the result of that effort is not exhaustive, we believe we have uncovered a representative sample of the state of the discipline in the country, especially considering the scarcity of academic work in the field.

Misconception

If we could summarize the trajectory of social marketing in Brazil in just one word, misconception would be the one. Social marketing in Brazil–and its Latin America neighbors–is usually confused with mere advertising, social communication, cause marketing or societal marketing (e.g. Almaraz, Gonzáles and Gárcia, 2009; Levek et al., 2002; Neves, 2001). The few professional articles aiming at business audiences usually try to entice companies to see the opportunity to gain a philanthropic affiliation or to market themselves to their internal public (i.e. employees).

In other words, almost anyone in Brazil, especially key social actors such as government officials and media pundits, knows about social marketing and its powerful set of tools for behavior change.

However, besides the misconception about the discipline, there is another barrier to the advancement of social marketing in Brazil: the prejudice against marketing–and even against the word “marketing”. Marketing has been associated with the worst practices in business: the selling of unhealthy food to children (Lang, Nascimento and Taddei, 2009), deception in sales, unethical “selling” of political candidates and so on. It has also been linked to a method for top-down control by international organizations, such as U.S. Agency for International Development (Dragon, 2004).

Nevertheless, while it is unsurprising that social marketing is still in its infancy in Brazil, over the last decades there have been some academic and practical advancement in the country. Social programs sometimes capture some of the main elements that comprise the tenets of social marketing: the 4 Ps, segmentation, consumer research, positioning, branding, etc. On the academic front, there have been studies employing the social marketing framework to study governmental programs and propose better courses of action. We first review the academic studies and then highlight important social programs that employed elements of marketing in their design.

Academic studies

When did the field of social marketing begin in Brazil? The answer lies in the academia. The first academic work that explicitly employed social marketing in the country was the doctoral thesis written by the first author of this article at the University of Sao Paulo (Mazzon, 1981). The author utilized the social marketing framework to analyze a major Brazilian governmental program (a worker food program) that wove a partnership between the federal government and firms to provide better nutrition to workers (PAT – Programa de Alimentação do Trabalhador).

In the last two decades, there have been very few academic studies using social marketing as a theoretical reference. Hence, the conciseness of the following list. Gonçalves (1991) discussed the possibilities of a broad application of social marketing to several problems of development in Brazil, in particular empowering people to tackle social challenges. Cerqueira (1997) found an incomplete application of social marketing tenets in recycling programs conducted by private companies, notwithstanding their successful outcomes. Popadiuk and Marcondes (2000) defended the use of social marketing to sell the benefits associated with the process of privatization that took place in the country at the turn of the century. Carvalho (2010) used social marketing to analyze the dissemination of a government program in the tax field–the conclusion was that a lack of social marketing orientation produced a costly program that did not meet its expectations of success and frustrated actual and potential consumers. Using qualitative methods, Meira (2010) developed a method to evaluate social marketing programs, identifying inputs, processes and results, and including an ethical dimension throughout the steps. Goto (2014) used social marketing as reference to propose actions to fight the dengue epidemics in the city of São Paulo. In a context of continuously increasing traffic accidents in Brazil, Dias (2015) contrasted the perception of a selected sample of individuals with the low efficacious campaigns sponsored by the federal government. In the same vein, Rezende et al. (2015) concluded that governmental efforts to stimulate organ donations in Brazil have a low efficacy, especially because they ignore the public’s perception regarding the safety of the procedures.

To summarize, a common thread linking most of the studies briefly described above is the general proposition that the low efficacy of social programs in Brazil derives from the incomplete use or absence of social marketing concepts and principles.

Key programs and initiatives

Following what happened worldwide since the beginning of the discipline, the most common application of social marketing in Brazil has been in the health field.

Nonetheless, the first government program explicitly using a social marketing approach was the Worker Food Program (PAT – Programa de Alimentação do Trabalhador) created by Brazilian federal government in 1976. The goal was to improve the quality of meals consumed by workers. By creating an alliance involving the government (who provided tax incentives), companies (interested in improving worker’s productivity) and unions, the program stroke a rare win-win agreement in a convoluted social environment, at a time when Brazil was still a non-democratic country.

Social marketing techniques were employed to influence the behaviors of target employers, unions and food providers. The program has reached a great degree of success and it has been replicated in other Latin American countries, like Mexico, Uruguay and Argentina. The program has generated several spillover and network effects, ranging from better motivation levels among workers and less job accidents to greater specialization in the meals industry. It has also increased the amount of taxes flowing to public coffers, generating US$ 15 in taxes for each US$ 1 waived by the government (Mazzon et al., 2016).

A landmark social program in Brazil has been the HIV prevention program. Traditional programs in this field tend to have a short-term duration and rely on communication, such as the Tú No Me Conoces (“You Don’t Know Me”) social marketing campaign that targeted the Hispanic population in the US-Mexico border (Olshefsky et al., 2007).

The Brazilian program started as a mass communication effort, initially using strong fear appeals. Over time it started adopting segmented communication with varying appeals and focus on a clear, specific and doable behavior (“wear condoms”). While not an authentic social marketing campaign, there are a few facts that make this program worth of mention. First, its consistency: it was developed without major political interferences through four different presidential terms, spanning a period of more than 20 years, a rarity in Brazil (Gutenberg, Fantini and Serpa, 2006). Secondly, over time its managers realized the power of research and segmentation and started to develop successful approaches to the most vulnerable population, including truck drivers, prostitutes, and pregnant women. Place and branding initiatives also comprised the set of interventions. Thirdly, as the costs to treat infected people started to mount (the drugs were offered free to patients), the Brazilian government decided in 2000 to unilaterally break drugs patents, forcing a decrease in their prices. This action infuriated the pharmaceutic industry, attracting a fierce opposition from the United States government, who decided to take the case to the World Trade Organization (WTO). The Brazilian government then took a rare approach: it started targeting upstream social actors (NGOs in developed countries, WTO decision makers, media gatekeepers), paying for ads in US newspapers and using several public relations tools. A United Nations conference on Aids in 2001 catalyzed the public opinion in favor of the Brazilian act, leading the US government to retreat and propose an agreement to end the dispute. Nowadays, the Brazilian program on HIV prevention and treatment is recognized as a benchmark in the field.

The Brazilian program on HIV prevention and treatment is recognized as a benchmark in the field.

Also in the health domain, another campaign that also had elements of a true social marketing program was the polio vaccination program (Ministério da Saúde, 2013). The Brazilian Ministry of Health promoted a cultural contest in schools in 1986 to choose a name for an advertising mascot. The name “Zé Gotinha” (something like “Joe Droplet”) was the winner and in a heartbeat the character became nationwide famous, with a huge appeal among children. Short animated films on TV, involvement of TV stars, production of comics, the presence of people wearing the character’s costumes at the public clinics and related initiatives helped to create a “culture of vaccination” that has been having enduring effects in the country. The program was a huge success. The last case of polio in Brazil dates back to the decade of 1980s, the same decade when polio was eradicated in Argentina (a smaller, more homogeneous country, with better educational levels) and a decade earlier than Mexico. Once employed to represent only oral vaccines against polio, “Zé Gotinha” has been used as a mascot in most mass vaccination campaigns that target children in Brazil.

A recent contribution to the expansion of social marketing came from the environmental NGO Rare. Rare employs techniques from the discipline to support conservation in local communities. It trains leaders from local communities with the goal of developing pride and empowering them to adopt sustainable practices in their lives. It now has offices in Brazil (since 2014) and Mexico (since 2008), with several ongoing projects in Latin America (Stoner, 2015).

The presence of some organized elements of marketing in social programs in Brazil is probably due to the dissemination of knowledge in management sciences. It is not rare to find staff with an undergraduate degree in business in the more organized Brazilian NGOs. Knowledge in marketing has also been helping civil servants in some rare cases. For instance, a current initiative, the campaign against dengue fever in the Brazilian city of Santos has made clever use of spokespersons, integrated marketing communication, social media, promotion, and place strategies (Prefeitura de Santos, n.d.).

On a final note in this section, communication campaigns are easy to identify in Brazil. Campaigns to inform the population about new laws are common. They fit the throwing food at the pigeons’ paradigm: just spread the information about the desired behavior and hope that the people pay attention and “bite” it. As expected, most of the potential for change is squandered.

Barriers and possibilities of expansion

Providing information with the hope of changing behaviors has been a hallmark in governmental (intended) behavior change programs, as Mazzon (1981) had already identified more than three decades ago. Marketing is sometimes the label of campaigns and programs that are, in essence, mere social communication. In addition, the academic production on social marketing in Brazil has been scarce, reflecting a stalled diffusion process. As Araújo (2011) argues, social marketing in the country suffers from misconception, lack of dissemination of best practices and the low level of academic production. This seems to be the case also in the rest of Latin America.

In a query in 2014 in the social marketing listserv, we probed the existence of other Latin America participants. There were only nine replies, most of them from people working with Rare in the region and only two professionals from Brazil. This seems a reflection of both the weak popularity of the discipline in the region and the fact that most of the work that approach the social marketing framework is performed by people who do not see themselves as social marketers (or ignore what social marketing is).

Is this sense, it is interesting to remark that, in a interview with a person involved in the Brazilian HIV program, we heard that using words in English is a sure way to close doors and shut off audiences in the federal government. Marketing is a “forbidden” word in the public field, he said. The resistance to marketing and the leadership by advertisers in the conduction of public campaigns even led academics and practitioners in that field to develop a discipline called “public interest communication” (Costa, 2006b).

Perhaps nothing is more telling about the status of marketing as discipline in Brazil than a recent lecture by a famous Brazilian professor, in which he dialogues with an imaginary student. “Asked” to read the first three pages of a Kant’s book, the student says he is not capable to do it. The professor then recommends that he gives up and accept his limitations given by nature. The recommendation is explicit: “go get Kotler’s book, it is your maximum, you have a (low) ceiling, the wind blows, the frog ‘frogs’ and you are a marketer” (available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qj6mQSdBSGI. The video has more than 1,173,700 views on YouTube as of April 2017.

Public executives may also be cautious in changing practices that seem to work. Most decisions and actions in organizational or social settings are subject to delays in producing results, which hinders organizational learning and limits the exploration of alternative courses of action (Rahmandad, 2008). Moreover, concrete outcomes typically result from several intertwined causes, many of them unobserved by the original decision maker. Hence, it is difficult to beat the illusion that some practices work or are the best alternative, when often they are sub-optimal, ineffective or even counter-productive.

However, even when marketing is accepted as a method or a philosophy to guide initiatives, it is usually considered as “1P marketing” (promotion), a problem that is not exclusive to Brazil (Lefebvre, 2011). Recently another approach in the communication field, the so-called social media marketing, has also been gaining prominence in Latin America.

Hence, the barriers to the expansion of social marketing in Brazil seem to be, in essence, lack of knowledge about the discipline, strong negative associations with marketing, lack of practitioners and programs creating visible results attributable to social marketing and, finally, concurrence with competing frameworks, namely education (social communication) and law.

Figure 2 summarizes those barriers using a causal loop diagram (Sterman, 2000). Essentially, as social marketing is rarely used, this prevents the occurrence of a virtuous cycle: increasing interest leading to more use and positive results, which, in turn, increase the knowledge about the discipline, sparking more interest and reinforcing the loop.

Nonetheless, the social problems that historically have attracted social marketers throughout the world remain strong in Brazil and other Latin American countries: health problems, tobacco industry targeting teenagers (Braun et al., 2008), access to public services, safety in roads, poverty, inequality, etc. Those problems still call for efficacious interventions.

If social marketing use is to expand in Brazil, there is need to act on some points in the social ecosystem where actors decide how to tackle the complex problems that afflict the country. In other words, there is need to identify points of intervention that put in motion the virtuous cycle depicted in Figure 2. To this end, we believe that the discipline’s own repertoire is useful to recommend some courses of action. We explore those possibilities below.

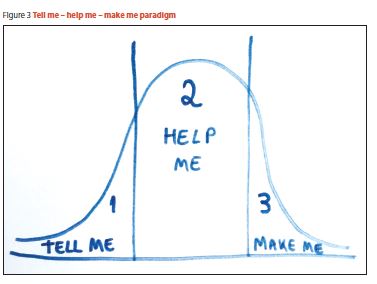

figure 3 presents graphically a heuristic widely known in social marketing (Lee and Kotler, 2015). The bell curve is assumed to represent the dispersion of willingness to perform a given behavior among the population. The throw-food-at-the-pigeons paradigm corresponds to the first segment (“tell me”), composed by people who will perform the intended behavior when given adequate information. It corresponds also to the innovators and early adopters’ groups found in diffusion of innovation models (e.g., Rogers, 1962). The third segment (“make me”) comprises people very resistant to comply. In fact, law and enforcement often are necessary to change the behavior of those people. Finally, the middle group (“help me”, group 2)–composed by early and late majority in diffusion models–congregates people who are somehow interested or at best no opposed to perform the intended behavior. Those people need help or otherwise this largest fraction of the population will not act as expected. The design of social marketing programs aiming at that numerous middle group typically remove barriers to behaviors, offer incentives and social proof, and make the expected behavior more accessible and convenient.

The same framework can be employed to diffuse social marketing among public executives and other social actors in Brazil. To this end, a four-stage process as suggested by Bandura (1997) seems adequate. The process involves selecting an optimal place in the social system for introducing the innovation; creating the necessary preconditions for change, such as providing knowledge and fostering attitudinal change; implementing an effective pilot program; and promoting the success from the pilot program as a means to diffuse the innovation.

In turn, the selection of an optimal place in the system involves the identification of key perceptions among the social actors capable of accelerating the diffusion. Those perceptions include, in particular, the elements of the BCOS framework proposed by Andreasen (1997): benefits, costs, others, and self-efficacy. In addition, considering the widespread negative associations with the word marketing in Brazil and the confusion between communication, advertising and marketing that seems present in the mind of important social actors, there is also an acute need for branding the discipline of social marketing. Branding is a necessary step to create positive and unique associations with the discipline and promoting its true essence (Aaker, 1991).

Based on this brief discussion, we propose an agenda of three points to accelerate the diffusion of social marketing in Brazil.

Conclusion: A three points agenda

Perhaps social marketing should reconsider the abandonment of selling ideas as its main goals without falling in the awareness trap. The need to sell ideas and frameworks seem more acute when one considers upstream social actors, the ones who decide which conceptual repertoire to use in social programs or who influence the decision-making process.

The general concept of marketing (Kotler, 1972) has yet to be fully accepted as a legitimate means in Brazil to accomplish goals of social interest. The competition occurs with other technologies for social change in the marketplace of ideas, in particular the wrong mental models about the true effectiveness of education and the law. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the perceptions of key social actors and develop a unique selling proposition for social marketing, weaving a compelling narrative that attenuates the negative associations with marketing and promotes the true essence of the discipline. This is the first point in an agenda to diffuse social marketing in Brazil: branding.

The second point is to identify campaigns and programs that represent positive deviations or “bright spots” (Heath and Heath, 2010) and people that can act as champions in the effort of diffusion. There are programs in Brazil that have been employing most of social marketing’s repertoire without recognizing or acknowledging it. This step encompasses the identification of people running those programs, social innovators willing to test new approaches and public executives with a background knowledge of marketing and business. It also comprises training people in social marketing and exposing potential adopters to the social proof: making the use and the results of social marketing highly visible. Bandura (1997) argues in the case of delayed and less obvious outcomes, people may be less motivated to act. The virtuous cycle depicted in Figure 2 will only produce its effects when key social actors realize the superior results springing from social marketing-inspired interventions.

Finally, to conduct a branding process and to target the most promising segment of social actors, there is need for collective and concerted action. Thus, the third point in the suggested agenda is the aggregation of academic and professional social marketers in Brazil (and perhaps Latin America) though the creation of a regional association. An association can develop financial, teaching and marketing capabilities to promote the diffusion of social marketing in the country. In the end, it is like moving the promotion of the discipline from its usual informational stage. Academics have been discussing how social marketing could achieve better results in social programs–this is the “tell me” approach. Only organized marketing programs can reach the voluminous “help me” segment.

To conclude, as Fox and Kotler (1980, p. 32) once remarked, there is “a need for more and better trained social marketers rather than simple social advertisers”. This remains truer than ever when one looks at the panorama of social marketing in Brazil.

References

AAKER, D. (1991), Managing Brand Equity. The Free Press, New York. [ Links ]

AGÊNCIA BRASIL (2010), “Propagandas de carro terão que veicular frases educativas”. Available at: http://noticias.r7.com/brasil/noticias/propagandas-de-carro-terao-que-veicular-frases-educativas-20100809.html, accessed 2 May 2017.

ALMARAZ, I.A.; GONZÁLEZ, M.B. & García, T.C.R. (2009), “Publicidad social en las ONG de Córdoba (Argentina): perfiles de la construcción del mensaje”. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 64, pp. 1011-1029.

ANDREASEN, A. (2006), Social Marketing in the 21st Century. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

ARAÚJO, E.T. (2011), “Marketing social aplicado a causas públicas: Cuidados e desafios metodológicos no planejamento das mudanças de comportamentos, atitudes e práticas sociais”. Revista Pensamento & Realidade, 26(3), pp. 77-100.

BANDURA, A. (1997), Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. W.H. Freeman and Company, New York. [ Links ]

BORNKESSEL, A. (2010), “Questions to prevent awareness fever”. Available at http://www.fly4change.com/questions-to-prevent-awareness-building-fever/1656/, accessed 30 April 2017.

BRAUN, S.; MEJIA, R.; LING, P.M. & Perez-Stable, E.J. (2008), “Tobacco industry targeting youth in Argentina”. Tobacco Control, 17(2), pp. 111-117.

CARVALHO, H. C. (2010), “O Governo quer que eu mude: Marketing social e comportamento do consumidor na adoção de um programa governamental”. Masters dissertation, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. Available at http://www.teses.usp.br, accessed 30 April 2017.

CARVALHO, H.C. & MAZZON, J.A. (2013), “Homo economicus and social marketing: Questioning traditional models of behavior”. Journal of Social Marketing, 3(2), pp. 162-175.

CERQUEIRA, C.F. (1997), “A questão da reciclagem de materiais sob o enfoque do marketing social”. Masters dissertation, Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, São Paulo. Available at http://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br, accessed 30 April 2017.

COSTA, J.R.V.D. (2006a) (Ed.), Comunicação de Interesse Público: Idéias que Movem Pessoas e Fazem um Mundo Melhor. Jaboticaba, São Paulo. [ Links ]

COSTA, J.R.V.D. (2006b), “A comunicação de interesse público”. In Costa, 2006a, pp. 20-27.

DIAS, R.G. (2015), “O uso de metáforas na análise da eficácia das campanhas de marketing social sobre a prevenção aos acidentes de trânsito: Um estudo com condutores habilitados”. Masters dissertation, Faculdade Novos Horizontes, Belo Horizonte. Available at http://www.unihorizontes.br, accessed 30 April 2017.

DRAGON, A.G. (2004), “El cuarto mosquetero: comunicación para el cambio social”. Investigación y desarrollo, 12(1), pp. 2-23.

FOX, K.F. & KOTLER, P. (1980), “The marketing of social causes: The first 10 years”. The Journal of Marketing, 44, pp. 24-33.

GOMES, L.F. (2014), “Gigante inacabado: Mortes no trânsito”. Available at http://institutoavantebrasil.com.br/gigante-inacabado-mortes-no-transito/, accessed 30 April 2017.

GONÇALVES, L.E.L. (1991), “Marketing social: A ótica, a ética e sua contribuição para o desenvolvimento da sociedade brasileira”. Masters dissertation, Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Rio de Janeiro. Available at http://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br, accessed 30 April 2017.

GOTO, L.F. (2014), “Crenças sobre a dengue entre residentes do município de São Paulo”. Unpublished manuscript, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo.

GUTENBERG, C.; FANTINI, F. & SERPA, F.C. (2006), “Cinco presidentes, uma só luta”. In Costa, 2006a, pp. 36-62.

HEATH, C. & HEATH, D. (2010), Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard. Random House, New York. [ Links ]

KOTLER, P. & ZALTMAN, G. (1971), “Social marketing: An approach to planned social change”. Journal of Marketing, 35(3), pp. 3-12.

KOTLER, P. (1972), “A generic concept of marketing”. The Journal of Marketing, 36, pp. 46-54.

LANG, R.M.; NASCIMENTO, A.N.D. & TADDEI, J.A. (2009), “A transição nutricional e a população infantojuvenil: Medidas de proteção contra o marketing de alimentos e bebidas prejudiciais à saúde”. Nutrire, 34(3), pp. 217-229.

LEE, N.R. & KOTLER, P. (2015), Social Marketing: Changing Behaviors for Good. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

LEFEBVRE, R.C. (2011), “An integrative model for social marketing”. Journal of Social Marketing, 1(1), pp. 54-72.

LEVEK, A.R.H.C.; BENAZZI, A.C.M.; ARNONE, J.R.F.; SEGUIN, J. & GERHARDT, T.M. (2002), “A responsabilidade social e sua interface com o marketing social”. Revista da FAE, 5(2), pp. 15-25.

MAZZON, J.A. (1981), “Análise do Programa de Alimentação do Trabalhador sob o conceito de marketing social”. Ph.D thesis, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo.

MAZZON, J.A.; BARROS, F.M.O.; ZILVETI, F.A.; ISABELLA, G.; CARVALHO, H.C.; MARQUES, J.A. & GUILHOTO, J.J.M. (2016), 40 Anos Programa de Alimentação do Trabalhador: Conquistas e Desafios da Política Nutricional com Foco em Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social. Blücher, São Paulo, SP. [ Links ]

MEIRA, P.R.S. (2010), “Programas de marketing social: Proposição e exame de uma estrutura conceitual de avaliação de resultados”. PhD thesis, Escola de Administração, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre. Available at http://www.lume.ufrgs.br; accessed 30 April 2017.

MINISTÉRIO DA SAÚDE (2013), “Zé Gotinha: Conheça a história do símbolo da vacinação no Brasil”. Available at www.blog.saude.gov.br/servicos/32941-zegotinha-conheca-a-historia-do-simbolo-da-vacinacao-no-brasil.html; accessed 30 April 2017.

NEVES, M. (2001), “Marketing Social no Brasil: A nova abordagem na era da gestão empresarial globalizada”. E-papers, São Paulo.

OLSHEFSKY, A.M.; ZIVE, M.M.; SCOLARI, R. & ZUÑIGA, M.L. (2007), “Promoting HIV risk awareness and testing in Latinos living on the US-Mexico border: the Tu No Me Conoces social marketing campaign”. AIDS Education & Prevention, 19(5), pp. 422-435.

POPADIUK, S. & MARCONDES, R.C. (2000), “Marketing social como instrumento facilitador de mudanças organizacionais: Uma aplicação ao processo de privatização”. Caderno de Pesquisas em Administração, 1(12), pp. 42-53.

PREFEITURA DE SANTOS (n.d.), “Combate à dengue”. Available at http://www.santos.sp.gov.br/?q=tags/combate-dengue, accessed 30 April 2017.

RAHMANDAD, H. (2008), “Effect of delays on complexity of organizational learning”. Management Science, 54(7), pp. 1297-1312.

REZENDE, L.B.O.; SOUSA, C.V.; PEREIRA, J.R. & REZENDE, L.O. (2015), “Doação de órgãos no Brasil: Uma análise das campanhas governamentais sob a perspectiva do marketing social”. REmark – Revista Brasileira de Marketing, 14(3), pp. 362-376.

ROGERS, E.M. (1962), Diffusion of Innovations. Free Press, New York. [ Links ]

STERMAN, J. (2000), Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World. McGraw-Hill, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

STONER, L. (2015), Personal Communication.

Received in May 2017 and accepted in September 2017

Recebido em maio de 2017 e aceite em setembro de 2017

Recibido en mayo de 2017 y aceptado en septiembre de 2017