Introduction

Since the 1990s, the historiography of twentieth-century European dictatorships, in particular those practicing mass dictatorship, has been marked by the innovative exploration of the relations between society and the secret police, and the issue of exposure to political violence more generally. In particular, historians of “everyday life” (Bergerson 2004; Bosworth 2005; Fitzpatrick 2000; Fitzpatrick and Lüdtke 2008; Fulbrook 2013; Lüdtke 1994; Lüdtke 2016) and “accusatory practices” (Bergemann 2019; Fitzpatrick 1996; Fitzpatrick and Gellately 1997; Gellately 1996; Johnson 2000; Nérard 2004) have restored the agency of common citizens subjected to violent dictatorships. In doing so, they have uncovered systems of social practices characterized by ambiguity, accommodation, or opportunism in relation to the authorities, all of which contributed to the perpetuation of the dictatorial order.

Research of this type remains inexistent on the Salazar regime and its secret police, the Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado (PIDE).1 Instead, the historiography of the PIDE has continued to assert a top-down approach to historical understanding, articulated along a morally-inflected narrative and centered on the PIDE’s modalities of political repression and the experience of its direct victims-that is, the small minority of citizens who actively opposed the New State. As a result, the experience and social practices of ordinary citizens have been overlooked.2

This article aims to understand why the victim-centered paradigm continues to dominate the academic field in Portugal. It posits as its underlying argument the notion that memory politics have been central in shaping the historiography of the PIDE. By this, I mean that the efforts to construct and preserve a certain social memory of the PIDE have contaminated the process of historical understanding by dictating which aspects of the secret police are studied and which are not.3 The historical study of the PIDE has in effect remained captive of memorial interests.

The article is organized in two parts. The first argues that, owing to the particular circumstances of the New State’s demise, the representation of the PIDE made during the revolutionary process of 1974-1975 left an enduring mark on public consciousness and, in doing so, lastingly fashioned the social memory of the PIDE. The second examines the historiography per se. It argues that, whether due to the open politicization of the PIDE as a subject of historical study or as the result of more prosaic factors inherent to Portugal’s civil society, the main works of history devoted to Salazar’s secret police have been marked by a stark process of “memorializing inflection” (Cubitt 2007: 52). Both factors have influenced how the PIDE is approached in scholarly terms. In the conclusion, I will suggest ways in which the study of the PIDE can be rethought, a process which, in the Portuguese case, implies both releasing the historiography from its current memorializing inflection and opening up the academic field to new research objects.

1 - The April Revolution: “Antifascist” Memory and Collective Remembrance

The downfall of the regime through the military coup of April 25, 1974 was followed by a period of “emancipated memory” (Loff 2014: 3), during which the narratives of the PIDE’s victims were widely disseminated. After forty-eight years of enforced silence, the “antifascist” memory of the PIDE effectively acquired national prominence and hegemonic status. It was to exert a lasting influence on the social memory of the PIDE. Before explaining the endurance of the “antifascist” memory of the PIDE, I shall briefly outline its principal features.

Among its multiple expressions, the post-1974 “emancipation of memory” gave rise to a spate of publications denouncing the crimes of the dictatorship. Between 1974 and 1977, thirty-two books were published in Portugal on the theme of Salazarist repression (Maués 2013: 408-409). Of these, nineteen were devoted to the experience of political prisoners. A further thirteen focused directly on the PIDE. This corpus of works offers a good access point to the representation of the PIDE made at the time.4 Four essential features may be highlighted.

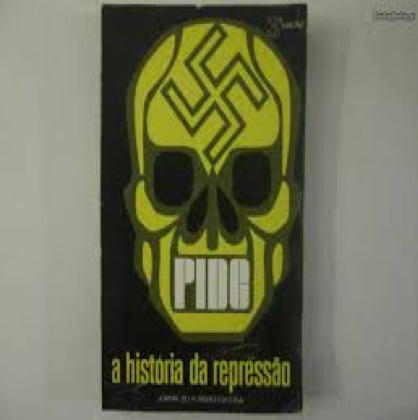

1.1 - The PIDE as the “Portuguese Gestapo”

A recurrent theme consisted in equating Salazar’s political police to the Gestapo. One publication from the corpus referred to the PIDE simply as the “Nazi police” (Reporter Sombra 1974: 37). Others noted that it had been “set up by the Gestapo” (Último relatório: “Nota prévia”) or that its methods were “Gestaponean [sic]” (Soares 1974: 52). Through a process known in the field of memory studies as “anchoring” (Paez et al 2015: N.p.), the intended effect was to ascribe a meaning to the PIDE by integrating it within an existing worldview-in this case, by anchoring it to the lineage of history’s most infamous institutions of repression.

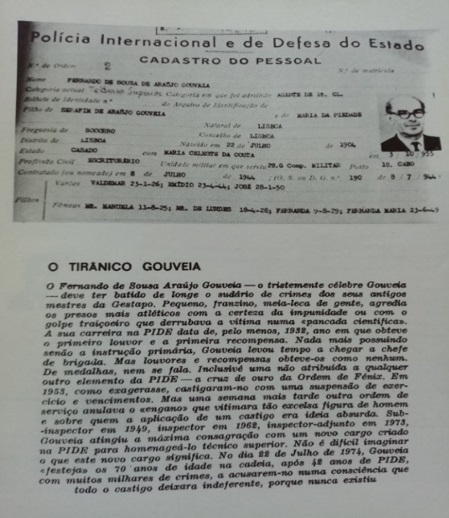

The corpus sometimes provided a more complete lineage. Thus, the PIDE’s “inhuman and often repugnant methods frequently came close to the inquisitorial systems consecrated by the Middle Ages and perfected by the Gestapo” (Manuel, Carapinha, and Neves 1974: 5). Fernando Luso Soares also presented the Inquisition as the PIDE’s “genuine predecessor” (Soares 1974: 17). The aim was to appropriate the Inquisition’s and the Gestapo’s global symbolic capital of evil, placing the PIDE on par with the ultimate expression of political violence. A well-established mode of representation was the “gallery” of its most infamous members, from Torquemada to Heinrich Himmler. The process was replicated in Portugal. One publication from the corpus included a thirty-page insert with biographical information on the PIDE’s principal carrascos (executioners), such as the “tyrannical Gouveia.”

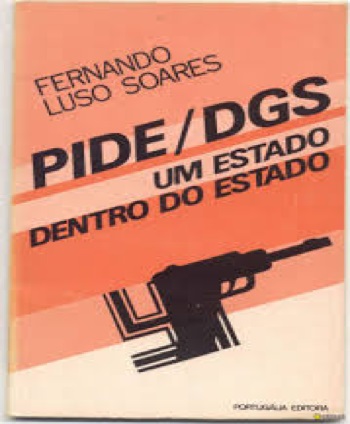

Mirroring the Gestapo, the PIDE was also repeatedly presented as a “State within the State.” According to this theory, the PIDE had grown to such a level of influence and power that it enjoyed almost complete autonomy in relation to the political authorities, if not precedence over them. Most of the arguments used were drawn from vague generalizations. Statements along the lines that the PIDE “dominated much of the national life until April 25” were taken as sufficient evidence of its status as a “State within the State” (Manuel, Carapinha, and Neves 1974: 6). A more substantive argument concerned the relations between the PIDE and the Plenary Tribunals, responsible for “political” cases between 1945 and 1974. Its judges were showed to “follow the directives and instructions of . . . the police” (A defesa acusa 1975: 9). One particular issue was the legal interdiction for lawyers to communicate with their clients during the investigative phase, including the interrogations, which effectively gave the PIDE a free hand in resorting to torture. Soares presented the case of a prisoner whose request for medical assistance had been denied by the PIDE. His lawyer’s appeal to the Ministry of Justice, under whose protection tutelage the prisoner remained in theory, also went unanswered. In practice, Soares concluded, “all the organs of (alleged) sovereignty bowed to this particular nature of the PIDE/DGS, that of a State within the State” (Soares 1974: 80).

Also, in Gestapo style, the PIDE was presented as omnipresent and omniscient. Its panoptic quality stemmed from its network of informers, those “men and women” acting as the “eyes and ears of Portuguese fascism” (Vasco 1977: 39). One publication estimated that, since its creation in 1945, some 200,000 “collaborators” had been involved in the PIDE’s activities, most of them informers (Manuel, Carapinha, and Neves 1974: 7). The PIDE had effectively “cast its net of informers throughout the country” (Elementos para a história da PIDE 1976: 3). Based on fragmentary archival evidence, impressionistic generalizations were made as to their motives, systematically presented as base and immoral. While some informers were “blackmailed” into the role (Vasco 1977: 49), most assumed the position for material gain. They reported on their fellow citizens in exchange for “some favor” bestowed by the PIDE (Vasco 1977: 39) or “for a few miserable escudos” (Manuel, Carapinha, and Neves 1974: 7). That some informers reported to the PIDE out of genuine support for the regime was rarely recognized. When it was, it was invariably in deprecating terms. In the words of Nuno Vasco, they acted “out of their sick devotion to the totalitarian regime” (Vasco 1977: 39).

1.2 - PIDE Agents as Quintessentially “Evil”

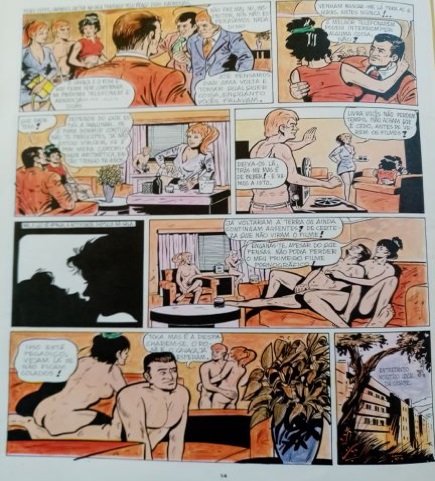

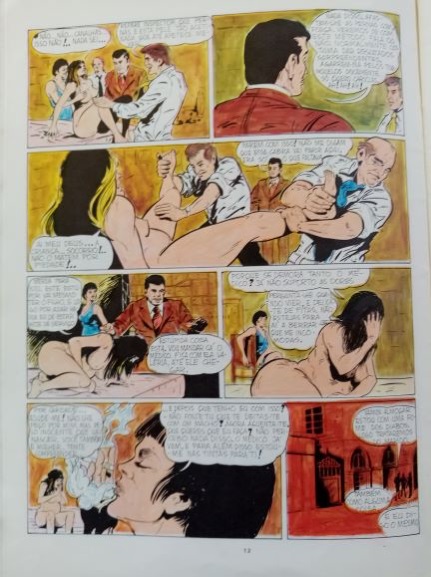

Another trait running through the corpus was the representation of PIDE agents as immoral in their behavior, Machiavellian in their methods, and sadistic in their practices. Driven by personal profit, the typical agent was naturally corrupt. Thus, agents stationed at frontier posts turned a blind eye to illegal contraband in return for a bribe (Elementos para a história da PIDE 1976: 35). The organization itself was riddled with “internal rivalries and personal jealousies” as agents vied for a position within the PIDE’s “complicated bureaucracy and rigid hierarchy” (Elementos para a história da PIDE 1976: 39). In Dossier PIDE/DGS, a widely-circulated comic-book series featuring the PIDE,5 agents were shown resorting to the services of prostitutes and depicted as regular consumers of pornography, thus highlighting their moral hypocrisy (Dossier PIDE/DGS. Na teia da PIDE 1975: 14).

The Machiavellian and sadistic personality traits of the PIDE agents showed in the way that they interrogated suspects. The typical agent “adapted himself to each particular case,” looking for opportunities to extract information from prisoners via their “family situation” or “the possibility of economic blackmail” (Elementos para a história da PIDE 1976: 31). The low level of education of the average agent was also heavily emphasized. Some agents were individually singled out. Thus, José Gonçalves, “who finished his career as sub-inspector, was semi-illiterate, as was Inspector Seixas” (Elementos para a história da PIDE 1976: 39). A whole narrative was developed from the theme of under-education, emphasizing the “uncivilized” nature of the PIDE as a police force. It was “not very important for the PIDE that its agents should be intellectually qualified.” Rather “what mattered more was their physical, ideological and political training as loyal lackeys of the regime” (Elementos para a história da PIDE 1976: 39). Also associated with their lack of formal education, the corpus utilized a semantic range that focused on the animalization of PIDE agents. These were referred to as “the guard dogs of fascism” (Elementos para a história da PIDE 1976: 3), “famished wolves” (Dossier PIDE/DGS: na teia da PIDE 1975: 11), “authentic wild beasts” (idem: 11), “disgusting swine” (idem: 19), “ferocious animals” (Reporter Sombra 1974: 8), or “repellent monsters” (Soares 1974: 57).

1.3 - The Focus on Violence and Torture

Each of the publications placed heavy emphasis on the high degree of violence employed by the PIDE, in particular its methods of torture (both physical and psychological), presented as the political police’s principal means of investigation. One recurrent feature was the graphic description of the most infamous of these methods, namely sleep deprivation and the so-called “statue” (during which prisoners were forced to remain in a standing position, often with their arms spread open, for several hours or days). First-hand accounts of former prisoners were systematically included for emotional effect. “There were various methods to prevent sleep,” one prisoner recalled. “The agent played with a coin on the table, rattled the drawers, ordered the prisoner to stand up or to walk across the room, etc. As days passed, the intensity of the stimuli increased: from loud bellowing to beatings; from playing recorded screams of pain to sudden changes in temperature; from the torment of the statue to burns; from arms raised in a cross-like position to the use of drugs” (Manuel, Carapinha, and Neves 1974: 110). Extensive accounts of the more “common” ill-treatments were also provided, such as slapping, kicking, or whipping. One particularly graphic representation of the PIDE, from the Dossier PIDE/DGS series, pictured PIDE agents torturing a pregnant woman.

1.4 - The “People as Victims”

Portuguese society as it was portrayed in these publications resembled the Arendtian model of the totalitarian “atomized” society. Despite the secrecy and censorship surrounding the PIDE’s activities, “its modes of action were known to large segments of the population” (Elementos para a história da PIDE 1976: 4). On the one hand, this meant that it was able to “instill so much terror into the people” (Dossier PIDE/DGS. Na teia da PIDE 1975: 27). On the other, the proliferation of informers led to “the moral degradation” of society (Soares 1974: 57). Individual citizens retreated to the private sphere, avoiding any activity that might bring them to the attention of the political police. Furthermore, a pervading sense of mutual suspicion took hold of society. As one of the publications put it, under the grip of the paralyzing fear instilled by the PIDE, “everyone distrusted everyone” (Manuel, Carapinha, and Neves 1974: 5).

The idea of the “people as victims” was also the logical consequence of the ostracizing of PIDE agents as psychopathic “monsters” during the revolutionary period. In the almost complete absence of higher-ranking figures of the regime, who had either fled the country or been allowed into exile, PIDE agents rapidly came to embody the paragons of the New State’s political violence, single-handedly responsible for Salazarist oppression. The notorious caça aos Pides (“hunting down of PIDE agents”) in the first weeks of the revolution was probably more complex a phenomenon than a simple surge of popular retribution. As the writer Miguel Torga, himself a victim of the PIDE, would write in his Diário, after witnessing the violent occupation of the secret police delegation in Coimbra on April 27 1974:

While I, along with other veterans of the opposition to fascism, witnessed the fury of a few exalted individuals calling for the slaughter of the agents holed up inside . . . , I thought of how these acts of revenge were rarely carried out by the actual victims of repression. There is in them a sense of decency [pudor] which does not allow them to sully their suffering. It is the others, those who did not suffer, who exceed all limits, as if from ill conscience and to show off a despair that they never actually experienced (qtd. in Araújo 2019: 73-74).

In this sense, the very notion of the “people as victims” was a convenient narrative for a society emerging from forty-eight years of dictatorial rule-a process reminiscent of the course of German society at the end of the Nazi regime, albeit on a much smaller scale. As a result, the relations between society and the PIDE were reduced to a dichotomist opposition between the persecuted and their oppressors, and more complex forms of interaction-not least the collaboration of many Portuguese citizens with the PIDE-kept well away from public scrutiny and arguably from social memory itself.

1.5 - “Antifascist” Memory as a Matrix of Collective Remembrance

To assess the precise influence of “antifascist” memory on the social memory of the PIDE would require a detailed diachronic account of the representations of the secret police since 1974, integrating the multitude of collective and individual actors involved in its construction-such as political parties, the media, and networks of private sociability. Such a task lies beyond the scope of this article. There are, nevertheless, plenty of indications suggesting that the influence of “antifascist” memory has been strong and enduring.

Notwithstanding phases of decreasing intensity of the remembrance process, in particular during the 1980s, and barring two notable exceptions,6 there is no evidence in the available literature to suggest that the socially legitimate representations of the PIDE produced since the revolution have differed substantially from the “antifascist” representation (though rid of its Marxist ideological wrapping). On the contrary, if the arts, broadly speaking, provide “a thermometer of the dominant values in a given society and a formative field for the symbolic representations of the past” (Napolitano 2015: 16-17), it would be hard to argue that the PIDE has been portrayed in any way other than through the prism of its function as a persecutor of the oppositionists and a general oppressor of the “people.” A cursory survey of some of the most popular “vehicles of memory” (Confino 1997: 1386) to have fashioned the social memory of the PIDE since 1974 supports this view.

In the literary field, examples abound of widely read novels in which persecution by the PIDE is an important part of the fictional narrative. Notwithstanding the differences in literary quality that exist between them, works such as José Saramago’s Levantado do chão (1980) and O ano da morte de Ricardo Reis (1984), much of António Lobo Antunes’s literary output, starting with his first two novels Memória de elefante (1979) and Os cus de Judas (1979), Antonio Tabucchi’s Afirma Pereira (1994), and the international best-sellers of foreign authors such as Robert Wilson’s A Small Death in Lisbon (1999) and Pascal Mercier’s Night Train to Lisbon (2004) have all, with varying degrees of subtlety, put forward representations of the PIDE as a brutal persecutor. Two of these novels were made into films-Afirma Pereira in 1996 (starring Marcello Mastroianni) and Night Train to Lisbon in 2013 (starring Jeremy Irons)-further enhancing their influence on social memory. The same victim-centered perspective is to be found in Susana de Sousa Dias’s multiple award-winning documentaries on the PIDE, such as 48 (2010) and Luz obscura (2017), the former consisting in a series of extended close-ups of the mugshots of political prisoners as they recount their memories of torture and humiliation at the hands of the PIDE.

In addition to the empirical evidence, theoretical notions pertaining to the field of memory studies must also be taken into account. That the revolution of April 25, 1974, and the events associated with it, should have registered with particular acuteness in the national consciousness is hardly surprising when seen from this viewpoint. The Portuguese case being one of rupture from the dictatorial past rather than a “negotiated transition” to democracy (Raimundo 2018: 17), it took place within a context of extraordinary revolutionary fervor, and led to profound social, political, and institutional change. As such, it constitutes one of those “key events, whose memory lives on (…), permeating society as a whole” (Rousso 1987: 11). The force of the revolutionary rupture, abruptly bringing to an end forty-eight years of uninterrupted dictatorship, also generated its own collectively-assumed “historical imaginary” (Fentress, and Wickham 1992: 129)-that is, a series of signifying images deeply ingrained into the public consciousness. One of these is the caça aos pides, diffused by the mass media on the occasion of each annual commemoration of the revolution (and not only), as evidence of the “people as victims” venting their fury against the “despised” political police. The so-called “recency bias” (Paez et al. 2015: n.p.) also placed the revolutionary events within the realm of “communicative memory” (Stelian 2013: 262), magnifying the potential for dissemination of the “people as victims” paradigm among the younger generations. Finally, stressing the PIDE’s repressive role also suited the increasingly consensual political discourse on the “democratic identity” of the nation after 1975, its collective remembrance serving as a kind of civic warning against the evils of dictatorship.

Surprisingly perhaps, the historiography of the PIDE has itself done little to provide a more nuanced and complete understanding of the secret police and its relationship with society in Salazar’s Portugal.

2 - Historiography: Between Revolutionary Tradition and Memorializing Inflection

The PIDE remains a particularly sensitive subject of academic research. This is due primarily to the fact that the historical works devoted to it have been inextricably enmeshed in memory politics (in part because several of the leading historians of the PIDE were themselves active oppositionists during the time of the New State). Consequently, the PIDE has been debated in no small measure in terms of present-day politics. The pervasiveness of memory in the field of historical research has operated in two ways: the first explicit, the second implicit.

2.1 - Guardians of the Revolutionary Tradition

The academic field has been framed to a large extent by those who may be designated the guardians of the revolutionary tradition, that is, of the orthodox representation of the PIDE constructed during the revolution, when the “antifascist” memory acquired hegemonic status. The virulent polemic that flared up amongst historians of the New State during the so-called “Verão Quente of 2012” (Meneses 2012) illustrates this phenomenon very clearly.

Much of the controversy that followed the serialization of Rui Ramos’ História de Portugal (Ramos 2009) centered precisely on the degree of political violence exercised by the regime, in particular the PIDE.7 In his work, Ramos essentially set out to relativize Salazarist political violence by placing it in a comparative perspective. The New State, he observed, “did not resort to the death penalty, assassinations were very rare and political prisoners few” (Ramos 2009: 652). In fact, the regime itself, Ramos further argued, had been “moderate” in its use of violence when compared not only to contemporaneous dictatorships, but also to the Portuguese First Republic and even to postwar democracies (Ramos 2009: 652).8 These arguments were sufficient to trigger a violent rebuttal from the guardians of the revolutionary tradition, for whom acknowledging the high level of political repression under the New State was a key component not only in their definition of the regime as “fascist” (Loff 2014: 7), but also in their interpretation of the April Revolution as the culmination of a popular “antifascist” struggle. The memorial mobilization of this vision of the past for present political purposes was particularly obvious at the time, namely in the idea that “if a popular struggle [had] defeated the New State, then it [could] defeat the EU/ECB/IMF ‘Troika’” (Meneses 2012: 75). In this context, rival representations of the PIDE were assumed to imply political plans of their own. The guardians of the revolutionary tradition, some with a significant influence in academia, effectively consider themselves to be engaged in a battle against what they see as a rightist agenda bent on erasing the memory of repression from the historical record so as to facilitate the implementation in the present of a “reactionary” political program. Any attempt to relativize the degree of political violence has consequently been seen as an attempt to “whitewash” the regime, a form of “negative” revisionism, if not plain “negationism” (Loff 2014: 10; Loff 2015: 66; Soutelo 2015). Rival interpretations of the regime have concomitantly been located as part of a “gigantic re-reading of world [history],” rooted in “historiographical revisionism” (such as relativizing political violence) and ultimately aimed at “legitimating the implementation of a neoconservative and neoliberal capitalist course” (Rosas 2016: 62).9

Two conclusions can be drawn from the above. The first is that the politicization of the PIDE as a subject of historical study has tended to further reinforce the analytical focus both on the degree of violence that it exercised and on the memory of its direct victims. The second is that the academic field as it currently stands in Portugal is hardly propitious to the application of new methodologies or the exploration of research objects that might run counter to the orthodox representation of the PIDE. Historians wishing to do so must assume the risk of exposing themselves to accusations of “negationism” and “whitewashing” in relation to the dictatorial past.

The guardians of the revolutionary tradition have not themselves produced any substantive research on the PIDE, but rather synthetic interpretive essays. Even the specialized historiography, however, has not remained immune to the influence of memorial interests, albeit as the result of societal circumstances rather than openly political factors.

2.2 - Memorializing Inflection

The (few) scholarly works devoted exclusively to the PIDE have displayed a strong memorializing inflection. By this, it is meant that these works have been influenced by their authors’ purposeful effort to uphold a certain memory of the PIDE. In doing so they have carried the victim-centered representations of the PIDE, typical of the “antifascist” memory, into the realm of historiography. Two influential works in this subject area will serve to demonstrate the point.

To this day, the only academic study to provide a broad history of the PIDE in mainland Portugal, from its creation in 1945 to its extinction in 1974, has been Irene Flunser Pimentel’s A História da PIDE (2007).10 Currently in its eighth edition-indicating, in theory at least, an exceptionally wide readership for a work of history-it has exerted a strong influence within the subject area. In this work, Pimentel develops her analysis along two lines. From the outset, the author places the study within broader considerations regarding the collective memory of the New State since 1974, thereby imbuing the analysis with an (implicit) memorial dimension. According to the author, “because of the political cleavages of the Hot Summer of 1975, a certain silence-although never total-covered the dictatorial past, as the struggle between the parties involved took precedence.” Following a period in the 1980s, during which “the memory of the dictatorship” was “repressed,” another phase began with the opening of the PIDE Archives to researchers in 1994. This in turn led to “a gradual lifting of the repression [of memory]” over the following decade which, according to Pimentel, “owed much to the work of historiography” (2007: 17). In practical terms, Pimentel’s own work was thus designed to contribute to “lifting” the silence still surrounding the activities of the PIDE. This type of approach had important consequences regarding which aspects of the PIDE were covered in the book. Again, from the outset, Pimentel stated her intention to study the PIDE “as an institution specialized (…) first and foremost in political repression.” For this reason, she explained, “the whole of the analysis” was to be “oriented towards the ‘relations’ between the PIDE and the members of the opposition to the New State, whether political, social or religious” (Pimentel 2007: 11). The work consequently delves at length in great depth into the experiences of the minority of oppositionists who were effectively persecuted by the PIDE (communists, republicans, socialists, progressive Catholics, and far-left groups, among others) and the modalities of repression used against them, with a heavy emphasis on their arbitrariness and brutality. Taken together, these aspects occupy four of the book’s five sections.11

If the work’s inherent memorializing intention accounts for its heavily victim-centered approach, it also explains why some of the PIDE’s more mundane tasks-such as internal administrative work and border control-were overlooked, and, more importantly, why the book largely ignored the experience of the population beyond the narrow circle of oppositionists. Indeed, whilst the role of paid informers is accounted for and the existence of a “culture of denunciation” among the public duly acknowledged-suggesting the presence of widespread practices of spontaneous, bottom-up interactions between society and the PIDE-the phenomenon is interpreted essentially as the unfortunate side-effect of a regime that encouraged that kind of behavior and as the Portuguese reality of a broader phenomenon that “tarnished the Twentieth Century” (Pimentel, 2007: 314 and 308-337). As a result, ordinary citizens have continued to be seen primarily as the passive victims of the PIDE’s fear-inducing impact on society. This was also a consequence of the way Pimentel envisaged the specific role of the PIDE within the regime’s broader apparatus of repression, namely as a “last resort” against “the few who fought against the New State” and a dissuasive influence on the rest of society (Pimentel 2007: 535).12

The emphasis on repression and the opposition also resulted from the fact that Pimentel’s work was the first detailed study of the PIDE after the opening of the PIDE Archives. As such, it logically focused on the secret police’s primarily repressive function, as had also been the case of the first (and sole) work devoted to the PIDE’s predecessor, the Polícia de Vigilância e Defesa do Estado (Ribeiro: 1995). Another factor in the discernible effort to uphold the memory of the victims of the PIDE was the perceived deficiency in the official recognition of this memory at the societal level, seen partly as a consequence of the lack of dynamism of civil society in Portugal (Pimentel 2017: 558). In such a context, historians took it upon themselves to contribute to the task.13

This was openly assumed in Vítimas de Salazar (2007), edited by João Madeira. Although devoted to political violence in general, rather than to the PIDE in particular, it has also exerted considerable influence in the subject area. The book itself was described by Madeira as a “collection of historical narratives of violence and resistance” that had been either “forgotten or devalued” by society. As such, it was intended as the response of a group of “civic-minded” historians to this lapse of memory (Madeira 2007: 32).14

The book’s table of contents certainly reads like an impressive list of the various types of political violence practiced by the New State, ranging from “concentration camps” and “violent deaths” to “phone-tapping and postal interception,” “deportation,” and “torture”-to cite only a few of the topics covered in its sixteen chapters. In his critical review of the book, Diego Palacios Cerezales has pointedly highlighted the pitfalls involved in a methodological approach grounded in the preservation of the memory of the victims of Salazarist violence (Cerezales 2007). By failing to introduce a comparative dimension to their study, not only do the authors tell us little about the specificities of police violence under Salazar, but, more importantly as concerns our present purposes, they also bypass fundamental aspects of the experience of political violence in Portugal itself. “The book,” Cerezales observes, “speaks of the experience of the victims, and at times one has the impression that all that existed was the regime on the one hand, and its victims on the other. The attitudes adopted in relation to State violence by the rest of the population are not sufficiently explored,” namely, “those who denounced it; those who knew and justified it; those who knew and remained silent” (Cerezales 2007: 1128).

By reducing the relations between society and the PIDE to a dichotomist opposition between persecutors and persecuted, victim-centered memorializing works are insufficient as an analytical framework to account for broader experiences of the PIDE across society. And yet, despite a recent and innovative monograph on one of the PIDE’s many paid informers (Silva 2019), developments in the historiography have actually tended to increase this dichotomy, whether by focusing on certain categories of victims, such as intellectuals and writers (Nunes 2007; Silva 2009), or on the perpetrators of political violence, such as the PIDE’s most “infamous” agents (Pimentel 2008; Pimentel 2019). Neither has the moralizing discourse typical of “antifascist” memory been expurgated from the historiographical narrative. It is significant from this viewpoint that Pimentel’s most recent work on the PIDE continues to refer to informers as engaging in “activities of treason” (Pimentel 2019: 391). None of these developments have been beneficial to the attainment of a more thorough understanding of the PIDE’s complex relation to society under Salazarism. By remaining a captive of memory, the historiography has arguably made this objective harder to achieve.

Conclusion

As a result of the enduring influence of the “antifascist” memory of the PIDE and the concomitant contamination of the field of historical research by memorial interests, both political and circumstantial, the historiography of the PIDE remains characterized by a markedly top-down, victim-centered approach to its subject. In this conclusion, I will suggest two directions in which historians can broaden the scope of their research beyond the traditional narrative of repression and violence.

The first relates to the way the PIDE is approached as an object of study. The aim is to arrive at a more dispassionate comprehension of the Salazarist secret police, overcoming in particular the caricature of the quintessentially “evil Pide” prevalent in Portugal today. One way of doing so consists in revisiting the memoirs and interviews of former PIDE agents. Systematically reduced to the status of biased “marginal memories,” these have so far been resorted to by historians either as a way of gaining some “insider’s knowledge” on the functioning of the PIDE as an institution, or for the “version of events” their authors provide on particular cases of political violence, such as the assassination of Humberto Delgado in February, 1965. Though relatively few (Casaco 2003; Gouveia 1979; Oliveira 2011; Santos 2000; Tíscar 2017; Vasco and Cardoso 1998; Vieira 2015), these memoirs provide valuable biographical information on the functionaries of the PIDE, in particular the circumstances that led them, as individual citizens, to join the secret police. A common theme is that the PIDE provided one of the few professional pathways available in a society largely devoid of opportunities for the impoverished, uneducated populace. Historians would do well to take such statements at face value rather than equate the under-education of secret police agents to the “coarseness” of the PIDE as a police entity. One obvious research theme here is how a society marked by endemic poverty might have provided a favorable recruiting ground for the PIDE in terms of functionaries and informers. The hypothesis is that material necessitousness, rather than simple fear and contempt, fashioned the relation between many ordinary citizens and the Salazarist secret police. Exactly to what extent this may have been the case remains to be determined by collecting and analyzing the numerous prospective application letters sent to the PIDE by individual citizens, held at the PIDE Archives and the Archives of the Ministry of the Interior.

A critical reading of the memoirs left by former agents also shows that the aim of PIDE agents was not necessarily to persecute the opposition. One former agent, Emídio Oliveira, joined the DGS after having been in contact with its agents at Faro airport, whose work there he “found interesting” (Oliveira 2011: 31). After passing the preparatory course in Lisbon, he was later deployed to the sub-post at Faro airport. There he dealt essentially with passport control in collaboration with customs services, occasionally expelling rowdy tourists and intercepting “dangerous drugs.” “My conviction,” he writes, “was not political. I believed that the DGS was a security force which, in collaboration with the other national authorities, guaranteed public order and the security of the population” (Oliveira 2011: 82). Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho himself, one of the “captains of April,” wrote in 1975 about his “conviction that out of a hundred functionaries of the ex-DGS . . . 60 to 70 have never beaten anyone in their life. . . The majority were simply functionaries of the State, ordinary family men who supported themselves and their relatives by working [for the DGS]” (Carvalho 1975: 49). To emphasize this point does not mean minimizing the violence inflicted upon many of the oppositionists to the regime. It does, however, mean that the PIDE’s position as a source of purely administrative employment must also be considered as part of its multifaceted relation with society.

The second direction in which historians can broaden the scope of their research is suggested by the international bibliography on secret policing in contemporaneous dictatorial regimes. This involves taking as an object of research an important, and hitherto ignored, dimension in the relation between society and the PIDE, namely by focusing on the broader population (or ordinary citizens) rather than on the small minority of oppositionists that has monopolized the attention of historians so far. This means studying the strategies that they resorted to as a means of adjusting to the existence of the secret police. These individual strategies ranged from avoidance and accommodation to opportunism and collaboration. Coping strategies such as “keeping one’s head down” or “building a nest” by retreating into the private sphere, to cite only one dimension of the adjustment process, have been the object of innovative academic research on contemporaneous dictatorships (Mailänder 2016: 399-411).

In the Portuguese case, historians can address such research questions through opinion surveying and oral history, at least as far as the final decade and a half of the regime is concerned. A longer timeframe can be covered by further exploring the archival material held at the PIDE Archives (amongst others) on the various forms of everyday interactions that developed between ordinary citizens and the PIDE during the regime’s prolonged existence. In addition to the already-mentioned prospective applications, these include spontaneous denunciation letters and the petitioning of PIDE agents. In each of these cases, individual citizens sought to instrumentalize the PIDE “from below,” often to attain personal objectives, but also to meet basic necessities through a patron-to-client relationship (Simpson 2018; Simpson 2020). As such, these everyday interactions not only suggest a far more interactive relation between society and the PIDE than does the traditional narrative of violence and repression, they also have much to reveal about the way power itself was conceived of and exercised by the New State. Ultimately, they denote a degree of normalization of the regime’s institutional framework by ordinary citizens, and a “grey zone” of interaction between them and the secret police, which must be taken into consideration if a more complex understanding of the PIDE’s place in Portuguese society under Salazar is to be reached, and if the social mechanisms contributing to the exceptional durability of the regime are to be duly accounted for.