Prelude

The period between the late eighteenth and late nineteenth centuries was a time of nationalism and great turmoil in Europe, with major political, social, and economic upheavals. It was the time of the Spring of Nations, with wave after wave of popular nationalist and liberal uprisings against absolutist regimes, causing many European royal houses to make statements about their sovereignty. It was also the age of Romanticism, a cultural movement that significantly shaped the arts, absorbing symbols and images of different collective identities and recovering their roots from the past, generally from the Middle Ages. And, furthermore, it was a time of chivalrous ideals and “new crusades against the Muslim infidels,” marked by various conflicts with the Ottoman Empire, which resulted in the independence of several Christian countries in Eastern Europe formerly under Ottoman rule, such as Greece, Romania, and Serbia.

Architecture also embodied the prevailing spirit of that time, adapting and reinventing itself according to values that drew their inspiration from the past. It was converted into a kind of repository for past memories and experiences that people somehow wished to see reincarnated. The typical architectural styles of the Middle Ages-the period in which the origins of many nations were considered to be rooted-began to reemerge and were revived once again. Medieval fortifications began to appear, identified with glorious events from the past, frequently linked to the defense of nations and the establishment of their independence. These monuments became territorial references and were clear statements of power by their rulers, as well as representing a source of nationalist pride among the people.

Fig. 1: Castellated Palace of Pena, Sintra. View from the southwest (photograph provided by the author).

The most paradigmatic case in Portugal was the construction of the nineteenth-century “castellated palace” of Pena in Sintra, the most emblematic Portuguese Romantic building. The uniqueness of the palatial complex (frequently referred to, throughout the nineteenth century, as a “castle,” “castellated palace,” “manor house,” or “palace”) left a deep impression on Portuguese nineteenth-century society. This can be seen, for instance, by the number of times that this castellated palace was mentioned in the nineteenth-century periodical press. It was referred to both in words and in pictures, as well as in the form of prints, engravings, and photographs (Santos 2007: 106-111).

Revivalist castles as symbolic and cultural paradigms

In 1838, as part of the program for the sale of assets appropriated by the National Treasury (Fazenda Nacional) through the confiscation of the estates and property of the extinct religious orders,1 the Board of Public Credit (Junta de Crédito Público) sold, by public auction, the abandoned Convent of Our Lady of Pena (Convento de Nossa Senhora da Pena) and its surrounding lands, located at the top of the Serra de Sintra. The Hieronymite convent had been built between 1503 and 1511, following the design of Diogo de Boytac (c. 1460-1528) or, according to other sources, Giovanni Potassi.2 In order to express his gratitude for the successful voyage to India of Vasco da Gama (1469-1524), King Manuel I (1469-1521) ordered the reconstruction of the small hermitage already existing there and its enlargement into a convent, which he then donated to the Order of Saint Jerome. The Serra de Sintra was already famous for its mystical aura, and the site where the convent was built was considered sacred because of an ancient legend-a miraculous image of Our Lady had supposedly been found there in the Middle Ages, prompting the construction of the hermitage in 1372, which thereafter became a place of pilgrimage.

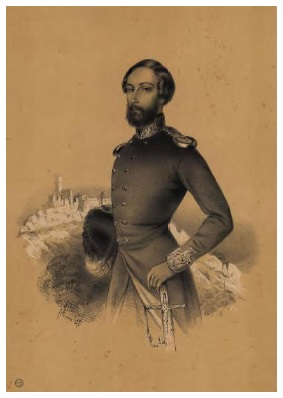

The sixteenth-century convent was bought by the Portuguese king, Fernando II (1816-1885), who, under the terms of the public purchase agreement, was compelled to carry out repairs to the former convent, as well as to preserve it as a national monument. Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the Portuguese king consort, who ruled under the name of Fernando II of Portugal, came from the aristocratic houses of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (of Germanic origin) and Koháry (of Magyar origin, part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). Born in Vienna, he was educated in accordance with the strict rules of Germanic aristocratic traditions.3 As a result of the prevailing cultural atmosphere at the small Central European court where he was raised, Fernando II had shown an interest in the arts from a very young age. His cultural knowledge contrasted with the generally conservative Portuguese mentality, especially after the period of isolation to which the country had been subjected due to the Napoleonic Invasions (1807-1810), the subsequent transfer of the Portuguese court to Brazil, the government of Portugal as a British protectorate, and the civil war between liberals and absolutists. After negotiations sponsored by the United Kingdom, Fernando II married the Portuguese Queen Maria II (1819-1853) in 1836.

Fernando II would already have known about Portugal through books, as can be seen by the trips that he made immediately after arriving in his new country. He visited the most important Portuguese architectural monuments described in travel books and other texts.4 Sintra, near Lisbon, would have been one of his favorite places, since it was greatly appreciated by the European Romantic culture; this can be seen in the words of the Scottish poet George Gordon Byron (1788-1824), who, in 1809, described Sintra as a “glorious Eden,” “perhaps, in every respect, the most delightful in Europe” (Byron 1837: 25).

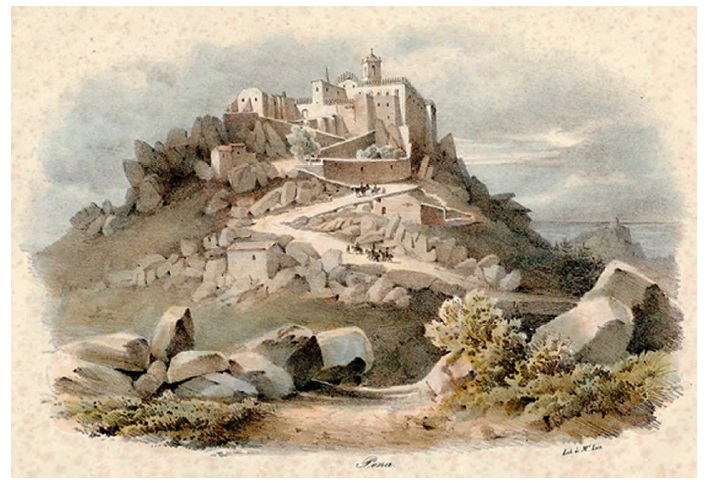

Fig. 2: Célestine Brélaz / Manuel Luís da Costa, Pena, 1840. View of the Royal Convent of Our Lady of Pena in Sintra (watercolor lithograph from the book by Célestine Brélaz, Croquis de Cintra: Dessinées d'Aprés Nature & Lithographiées).

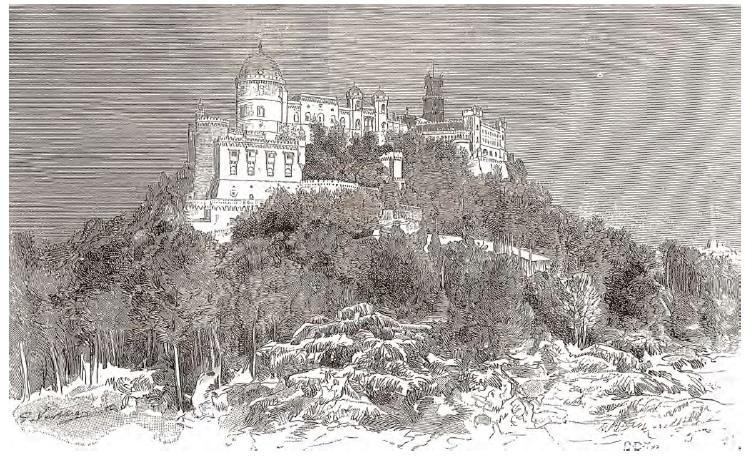

Fig. 3: [Illegible name], [Castellated Palace of Pena], 1886 steel engraving from the illustrated periodical A Illustração).

The former convent in Sintra acquired by Fernando II was a complex of buildings set atop one of the wild peaks of the Serra. It enjoyed a privileged location, shrouded in the Romantic mysticism of Sintra, which was famous for its shadowy forests and steep crags, filled with ancient ruins and abandoned castles, and with the infinite sea at its feet. These phenomena were seen and described by Byron, and it is almost certain that Fernando II would have read his poem before arriving in Portugal.

After some works had been undertaken for the repair, restoration, and remodeling of the former convent, designed to transform it into a place that would be suitable for the royal family to enjoy short stays in Sintra, Fernando II realized that the ancient structure did not offer the appropriate conditions of habitability, comfort, and dignity required by a royal residence. Consequently, in 1841, an ambitious program for the enlargement of the building was decided upon, involving the addition of newly built structures to the former convent. Once it was finished, the new royal residential complex of Pena displayed a series of features that led to its being classified as a “castellated palace”: the existence of a barbican with a fortified gate and drawbridge; the proliferation of battlements across almost the whole of the built complex; the round and polygonal buttresses, reminiscent of medieval bastions; the numerous bartizans around the palatial building; and the various towers, with the enormous cylindrical tower being the most prominent, together with the clock tower, evocative of the medieval keeps that are to be found in almost all Portuguese castles. Furthermore, the residential space itself resembled the palatial manor houses that had previously existed inside many medieval castles. Finally, this royal complex had a similar location to most Portuguese medieval castles, being situated in a high and easily defensible position.

However, the nineteenth-century castle of Pena did not perform any military function. Almost all of the architectural elements displaying military characteristics were mere decorative ornaments. The palatial complex of Pena was created within the context of the Romantic movement that was flourishing in Europe at that time. This movement had a huge impact on the (north and central) Germanic areas of the continent and in the United Kingdom. Romantics were greatly attracted to the medieval period, admiring the ideals of chivalry, the devotional sense of the Christian faith, and the corporatism of the arts and crafts. Architecture sought to reflect those ideals, searching for references in medieval styles and reinterpreting and adapting them to contemporary needs. For instance, revivalist architecture5 was expressed in the building of new churches, which began to adopt medieval aesthetic elements, inspired by the great cathedrals and monastic structures from the “time of the crusades and pilgrimages.”

While, for religious buildings there was a linear correlation with medieval temples, in the case of aristocratic residences, the sources of inspiration were usually medieval castles and castellated palaces, precisely because of the Romantic chivalrous ideals associated with legendary kings and knights, and their heroic deeds.6 Imbued with the Romantic ideals that he had acquired during his education, Fernando II opted to use an aesthetic solution for his new castle that was inspired by medieval military architecture, especially because Sintra, where his new royal residence would be located, was associated with Romantic mysticism.

The neo-Gothic revival provided visual associations with Gothic ornaments, while also displaying planimetric and volumetric asymmetries and creating the illusion that the buildings had been constructed over a long period of time, thereby eliciting the sensation of time passing through them. The rejection of the strict rules of Classicism, in favor of a dynamic system that could be adapted to different circumstances, allowed for greater flexibility in the use of architectural languages, forms, materials, and solutions. The Romantics’ fondness for medieval castles was not surprising: besides their political and social symbolism, the evolution and the changing uses that were made of castles (for example, the switch from military to residential functions) allowed them to incorporate one of the most favorite Romantic themes-the passage of time. Medieval castles enabled Romantics to observe their beginning, their evolution, and, ultimately, the end of their life cycle.

Between the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries, this same Romantic fascination was visible in Britain, where there were clear signs of an intense construction of aristocratic and upper middle-class residences, generally in the countryside. Numerous interventions were made on castellated palaces in order to enlarge them and endow them with better living conditions. The largest interventions included the demolition and subsequent reconstruction of medieval buildings, as well as the reformulation of pre-existing buildings and the incorporation of extensive enlargements. In both cases, the medieval appearance of these buildings was usually modified in some way. However, it should be noted that, even after this, in Britain, interventions continued to be performed on medieval structures in order to modernize them aesthetically and functionally and to adapt them to new needs. Generally speaking, the changes made before the Romantic period had usually been based on contemporary architectural aesthetics.

However, from the eighteenth century onwards, medieval architectural aesthetics began to be used in new interventions, particularly in the case of neo-medieval decorative elements. These new expressions assumed a symbolic dimension, adding new aesthetic values to buildings. Castellated residences were associated with a certain political and social prestige, which was further amplified by the influence of the Romantic movement, due to its attraction for the Middle Ages and the fascination that it had with mythical characters and medieval heroes. While some medieval aristocratic houses maintained their military appearance (although most of them were either partly or totally rebuilt), in other cases these buildings transformed their image and started to resemble palatial residences, despite maintaining some decorative elements that were simply a reference to medieval defensive architecture, such as battlements. Together with the renovation of those pre-existing aristocratic buildings, there was also an increase in the construction of new castellated mansions.

But the castellated Palace of Pena was certainly influenced, in the first place, by what was happening in Germanic areas-a nationalist reaction against the French invasions and the creation of new states and borders established by the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815). Fernando II was the nephew of Duke Ernest I (1784-1844) of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and, in his childhood, he had stayed with his uncle in Thuringia on various occasions. Fernando II was familiar with the ducal palaces in Thuringia, which had been substantially remodeled at his uncle’s orders (Teixeira 1986: 17). The remodeling of the palaces of Rosenau (Oeslau), Ehrenburg (Coburg), Callenberg (Beiersdorf), Reinhardsbrunn (Friedrichroda), and Veste Coburg (Coburg) gave them a Gothic or a castellated appearance. The first two buildings were designed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841), and the last two by Karl Alexander von Heideloff (1789-1865), while the architect of the remodel at Callenberg is unknown.

The Napoleonic Wars had an enormous impact in the Germanic area. The Rhine region fell temporarily under French rule and suffered severe destruction. In this way, the Napoleonic army aroused a strong nationalist resistance to the French presence. After its liberation from the French, this region began to be considered a kind of national sanctuary and a symbol of the pan-Germanic unity against foreign invaders. Ruined medieval fortifications began to be rebuilt and restored gradually, due to their symbolic links with the defense of the Germanic motherland and, at the same time, their medieval roots in the origin of the German nation. Naturally, numerous castellated palaces were either built or rebuilt with a medieval inspiration, displaying both symbolic and political motivations, including the Germanic territorial claims, and the proclamation of the hegemony of Germanic dynasties.

For instance, in the Rhine valley, the Prussian King Frederic William IV (1795-1861) promoted the reconstruction of the castellated palaces of Stolzenfels (Coblenz) and Sooneck (Niederheimbach), while his cousin, Prince Frederick of Prussia (1794-1863), did the same with the castellated palace of Rheinstein (Trechtingshausen). Much later, the castles of Hohkönigsburg (Orschwiller) and Ordensburg Marienburg (Malbork) were reconstructed, respectively in the western and eastern extremes of the Germanic territory, in an attempting to assert the Germanic territorial dominance there.7 The Prussian dynasty promoted the construction of Babelsberg Palace (Potsdam) and the rebuilding of the castellated palace of Hohenzollern (Hechingen), the Bavarian King Maximilian II (1811-1864) ordered the building of the castellated palace of Hohenschwangau, and the mythical Wartburg Castle (Eisenach) was also rebuilt in Thuringia.

Germanic Romanticism also conveyed the ideals of the crusades against the infidels. This can easily be seen by looking at the support that the Germanic monarchs gave to those countries that had recently been liberated from Ottoman (Muslim) rule.8 Moreover, there was also a highly evident admiration for the Teutonic knights, as well as for the mythical stories related with the medieval era.

Returning to the case of Portugal, the castellated Palace of Pena and its architectural features curiously bore a close resemblance to those of the castellated palace of Reinhardsbrunn, remodeled by Duke Ernest I. Just like the Portuguese palace, this Germanic palatial complex had its origin in a medieval monastic building-in this case, a Benedictine abbey. The ruined abbey had been bought by the ducal family, who converted it into a castellated palace to be used as a holiday residence, creating a luxuriant green park around the various buildings. As for the composite model of the castellated Palace of Pena, with its irregular planimetry, volumetry, and spatial organization, some affinities can be found with the Veste Coburg Castle (as well as other Germanic castellated palaces, such as the mythical Wartburg Castle in Eisenach). All of these had a series of both curved and straight blocks, linking together various volumes that had been adapted to the topography and characteristics of the landscape.

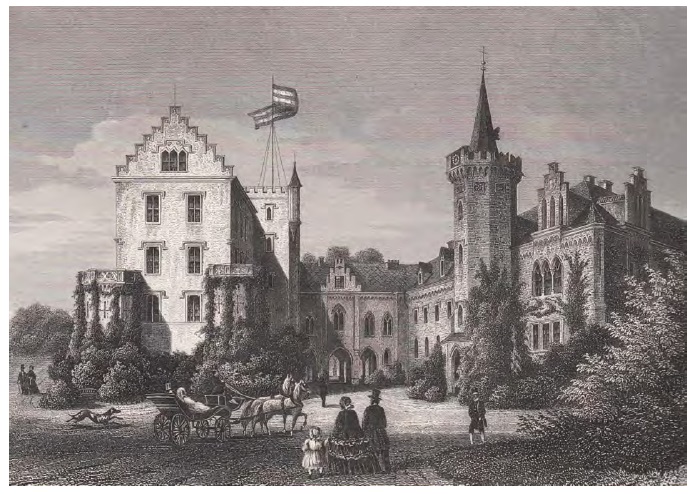

Fig. 4: F. Schack/Joseph Maximilian Kolb, Schloß Reinhardsbrunn, c. 1870 (steel engraving published by the Bibliographisches Institut Hildburghausen).

The volumetric plasticity of the castellated Palace of Pena did not result from the fact that the buildings had all been erected at the same time. On the contrary, it was the sum of the various volumes that had been added to an already pre-existing building. The irregular topography of the land on which the castellated palace of Sintra was built imposed certain restrictions on the new constructions, consequently calling for an organic interconnection of its different parts (Anacleto 1994: 211). It is significant that when the Prussian envoy to Portugal, Prince Felix Andreas Lichnowsky (1814-1848), was invited by Fernando II to visit the castellated Palace of Pena, he immediately drew comparisons with the castellated buildings of the Rhine Valley and Bavaria:

There are castles of kings and princes to be found in the Rhine Valley and the Bavarian Alps, all of which were erected in areas that allowed for their greater extension, achieving the honor of being frequently celebrated in prose or verse; and yet their ornamentation would look poor and imperfect if compared with the delicate knotwork and fantastic arabesques above the arcades of the Pena Palace. (Lichnowsky 1845: 126-127)

The resemblances between the Portuguese construction and some Germanic castellated palaces were clearly visible, for example, in their similar composite architectural models, their idealized Romantic revivalism, and the settings chosen for the location of the palatial complexes, atop the picturesque wild peaks of hills surrounded by thick, luxuriant vegetation.9

Besides Fernando II’s Romantic ideals, there were other motivations behind the sovereign’s intentions. The Portuguese king-consort was a foreigner, and therefore he was regarded with suspicion by a part of Portuguese society. Furthermore, Fernando II had arrived in Portugal immediately after the civil war, at a time of great political commotion and social discontent. The prestige of the Portuguese monarchy had been weakened by what was generally considered to be its cowardly escape to Brazil during the Napoleonic invasion, so that it needed to reaffirm itself not only as a stable and neutral institution in Portugal, but also as a generator of consensus between political and social sectors. Moreover, the supporters of Miguel I-the uncle of Queen Maria II-were still claiming his legitimate right to the Portuguese throne.10 As a consequence, the Portuguese royal family felt the need to symbolically assert its regal power, which could be partly achieved by building a new royal castle-or, in this case, a royal castellated palace.

Royal palaces had existed in Portugal since the Middle Ages, most of them being located inside defensive complexes.11 Furthermore, the building of a royal residence with a fortified structure was not merely a protective option; it was also a way of illustrating the owner’s prestige. The importance of military symbolism as a statement of power is also to be noted in the terms of the nuptial agreement: despite the controversy that this provoked in Portugal, the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha uncompromisingly demanded that Fernando II be granted the rank of Marshal and Commander-in-Chief of the Portuguese Army (Teixeira 1986: 37). The symbolism that is linked to certain military architectural aesthetics, as displayed in both medieval and modern buildings, can be observed in the ius crenelandi, the application of which was entirely dependent on the monarch. In Portugal, almost all fortifications formed part of the royal property, so that castellated palaces were unusual-they were granted by the king exclusively to a few aristocrats.12

During the nineteenth century, Portugal was no different from other European countries regarding the need to assert the sovereign’s authority. One of the ways of doing this was precisely to build or rebuild medievalized castellated palaces, just as many other kings had done in the past. Queen Victoria I of the United Kingdom (1819-1901), whose ancestry was almost entirely Germanic, was the niece of Duke Ernest I of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and married her cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819-1861), the duke’s son. Fernando II of Portugal was therefore a direct cousin of the British royal couple. As was the case with the Portuguese royal house, the British sovereigns somehow felt the need to legitimize their royal authority; besides this, as foreign king-consorts, both cousins (Fernando and Albert) wished to obtain their subjects’ approval by showing that they embraced the values of their new countries.

Some years after their marriage, in 1852, Victoria and Albert bought the ancient castellated complex of Balmoral, in Scotland, which had been remodeled between 1834 and 1838, when it was afforded a Tudor appearance. The British monarchs ordered a partial demolition of the ancient building, subsequently promoting the construction of a castellated palace on top of the pre-existing one, making it their summer residence. Besides some Germanic influences, the castellated palace of Balmoral, rebuilt between 1853 and 1857 in accordance with a design produced by Albert with the aid of the architect William Smith (1817-1891), also displayed regional influences related with the baronial architectural language of the Scottish Highlands.

Eclecticism and the debate on national architectural styles

Besides Fernando II’s origins and his consequent cultural influences, Portugal’s affinities with the Germanic world were further extended through the construction of the castellated Palace of Pena. Wilhelm Ludwig (1777-1855), Baron of Eschwege and a man of Germanic origin, was appointed by the Portuguese monarch to plan his new castellated palace in Sintra. Eschwege was a military engineer from the Rhenish region of Hesse-Kassel, near Thuringia, who arrived in Portugal in 1807. His educational background was strictly scientific in nature, although he had had some practice in the planning of architecture, which enabled him to propose a design based on academic models and in keeping with the predominant architectural tastes. As was the case with other Germanic architectural planners, Eschwege would have drawn his inspiration from publications reproducing pictures of British revivalist cottages and castellated palaces.13 Eschwege had also been influenced in architectural terms by Heinrich Cristoph Jussow (1754-1825), the architect who had designed the castellated palace of Löwenburg (Kassel), located close to Eschwege’s hometown. This palace, a false ruin of a medieval castle, was built between 1793 and 1800, and Eschwege probably adopted some influences from this building in the planning of his Sintra design (Hanschake 2009: 98). Furthermore, Eschwege lived in Prussia between 1829 and 1835, a time when Rhenish aristocratic homes were the subject of an enormous building campaign, and some of their designs were certainly influenced by British publications (Teixeira 1986: 307).

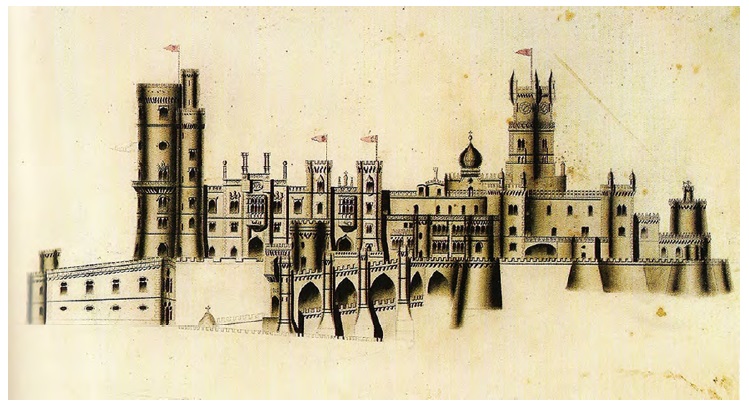

Eschwege’s initial designs for the new royal palace in Sintra displayed close similarities with some British and Germanic castellated palaces. The work for the construction of the Babelsberg Palace-the new holiday residence of the Prussian royal family, built between 1835 and 1849 in keeping with the designs by Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841), Johann Heinrich Strack (1805-1880), and Friedrich Ludwig Persius (1803-1845)-began during Eschwege’s stay in Prussia (Teixeira 1986: 308). Analyzing Eschwege’s design for the castellated Palace of Pena, it is easy to find affinities with the Germanic palace: a sober neo-Gothic language, with pointed motifs and allusions to medieval defensive architecture (tower and battlements); the planimetric asymmetry of the two buildings and perhaps the most clearly visible feature; and the longitudinal volume that, beginning with the complex of differently-sized volumes, ended at the other extreme in a large cylindrical tower with an even higher cylindrical turret. Both the tower and the turret were crowned with battlements and friezes of arches.

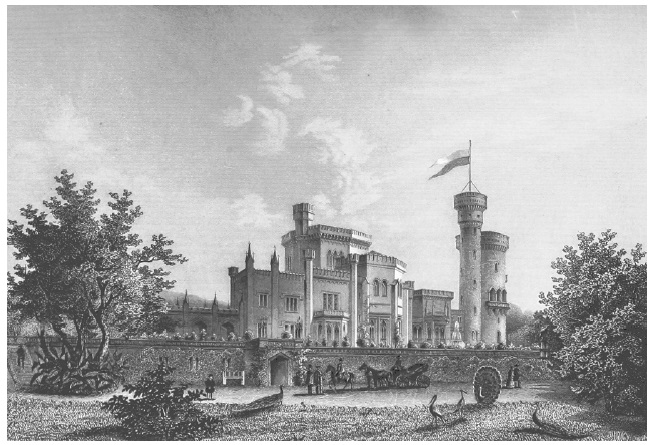

Fig. 5: F. A. Borchel / G. Hels, Schloss Babelsberg bei Potsdam, 1852 (steel engraving from the book by Johann Gabriel Friedrich Poppel, Das Königreich Preussen in malerischen Original-Ansichten seiner interessantesten Gegenden…).

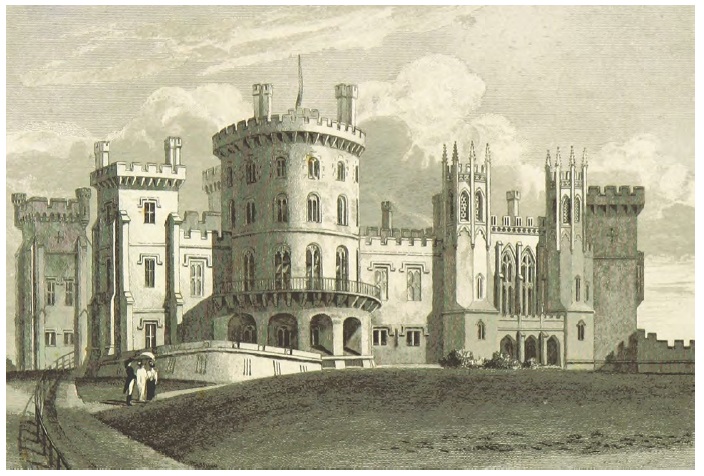

On the other hand, despite the planimetric differences, the Babelsberg Palace had certain affinities with some British buildings; for example, Belvoir Castle (Redmile), designed by James Wyatt (1736-1813) and rebuilt between 1801 and 1832. These similarities could be seen in the castle’s neo-Gothic sobriety, the use of buttresses and, above all, the cylindrical tower. Although it was not an end element, as in the Prussian palace, the volume and shape of the cylindrical tower in the British building are similar in both palaces, involving such features as the joining together of the cylindrical tower and the higher turret, the crown of battlements on both buildings, and the friezes of arches.14 As far as the castellated Palace of Pena is concerned, besides the similarities that it displays with the British castle and the Prussian palace in terms of the cylindrical tower and turret, the pointed arches, the battlements, and the friezes of arches, another coincidence can be observed between the Portuguese building and Belvoir Castle: two turrets signaling the main entrance.15

Fig. 6: John Preston Neale / William John Cooke, Belvoir Castle, Leicestershire, 1818 (steel engraving from the book by John Preston Neale, Views of the Seats of Noblemen and Gentlemen in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland).

Fernando II did not agree with Eschwege’s aesthetics in the first design for the castellated Palace of Pena, for which the neo-Gothic style was proposed. The Portuguese king was obliged by the purchase agreement to conserve the pre-existing convent, so he requested the use of an architectural language that was more in keeping with the sixteenth-century Convent of Our Lady of Pena (Teixeira 1996: 308). Besides the fact that he was building a monument, Fernando II would also have considered that the ancient convent, which was the origin of the new palatial complex, should be respected. He thus gave greater emphasis to the sixteenth-century Portuguese architectural influences coming from the convent than to the Germanic and British neo-Gothic influences proposed by Eschwege. In this way, Fernando II recognized the existence of specific features in Portuguese architecture, identifying a sort of national architectural language that was different from the ones existing in other countries.

Fig. 7: Wilhelm Ludwig von Eschwege (attrib.), [Plan for the Castellated Palace of Pena in Sintra], c.1838-42 (image provided by Parques de Sintra-Monte da Lua).

The debate on national styles was indeed of major interest to the European cultural elites of the nineteenth century. The “rise of nations” in nineteenth-century Europe inspired the search for a national architectural style, supposedly rooted in the past. After a nation’s language, its architecture was the most visible and tangible source for identifying a culture that was distinct from others, thus enabling the transmission of national historical roots. From the architectural point of view, the end of the Baroque era, culminating in the splendor of Rococo, resulted in a subsequently ambiguous period, due to the difficulty in creating a new architectural style to succeed the previous ones. Architecture has always been a reflection of the society that creates and maintains it, but it is also a representative symbol of the forces that lie behind its formation (political, religious, social, economic, etc.). At a time when History was a factor that characterized the beginning of the Contemporary Age (searching for the patriotic roots of nations and creating their identities), Architecture itself was hugely influenced by historicism. Therefore, the historicist spirit was incorporated into architecture, reinventing itself according to ancestral values-architecture could be a repository for memories or past experiences that one wished to be recorded or relived, or it could simply be a receiver of revivalist architectural elements and aesthetic ornaments.

While the quest for classicism in architecture was not an innovative attitude, the stylistic regression to the Middle Ages nonetheless sparked an intense and constructive debate on the paths of architecture at that time. For instance, Thomas Hope (1769-1831), Heinrich Hübsch (1795-1863), Gottfried Semper (1803-1879), César Denis Daly (1811-1894), Camillo Boito (1836-1914), Lluís Domènech i Montaner (1850-1923), Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) and John Ruskin (1819-1900), or, in Portugal, Joaquim Possidónio da Silva (1806-1896), all questioned which architectural styles should be used to build a contemporary architecture that embraced evolution but, at the same time, respected national traditions. The result was the predominance of an architectural eclecticism for a long period of time, from the end of the eighteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century. Eclectic architectural styles were characterized by the use of a diverse repertoire directly inspired by architectural languages from the past (neo-Romanesque, neo-Gothic, neo-Classical, neo-Moorish, neo-Manueline, neo-Byzantine, and neo-Baroque, as well as influences from Persian, Indian, Chinese, Japanese, and even African and Native American architecture). In this way, there was a free recreation of built structures, symbols, or a simple aesthetic sense, randomly incorporating various eclectic ornaments into architecture for picturesque and aesthetic purposes.

At that specific time in the nineteenth century, the debate on the Portuguese national architectural style was just beginning; nevertheless, there was already a strong nostalgic appeal of the architecture from the “golden era of the Portuguese Discoveries,” and, in particular, from the time of King Manuel I of Portugal. This appeal became even more visible at the beginning of the Romantic movement in Portugal, with the publication of the poem Camões in 1825 by João de Almeida Garrett (1799-1854). This poem was closely associated not only with the Portuguese poet Luís Vaz de Camões (c.1524-1580)-who wrote the epic poem Os Lusíadas, glorifying Portugal and the Portuguese overseas expansion-but also with the Portuguese Discoveries themselves as the symbol of the mythical “glorious Portuguese period.” This period was personified by Manuel I and by the monuments that were built in his time, namely the Hieronymite Monastery of Saint Mary of Belém (better known as the Jerónimos Monastery) and the fortified tower of Saint Vincent in Belém (or the Belém Tower), both in Lisbon; in fact, Garrett’s poem was also a kind of eulogy of the Portuguese virtues of that time (Maia 2007: 121).

Fernando II was aware of the legendary presence of Manuel I at the Convent of Our Lady of Pena. As a matter of fact, there was a myth that was frequently recounted, describing how Manuel I watched, from this convent, as the vessels of Vasco da Gama’s fleet returned triumphantly after discovering the maritime route to India. Fernando II surely intended to elevate the memory of Manuel I by assuming the legacy of the great Portuguese royal tradition. By doing so, he was establishing a continuity-he was taking on the role of the heir to the Portuguese dynasty, and, in this case, symbolically restoring the aura of the most glorious Portuguese king, who ruled over a vast empire that spread all around the world. In fact, there is a stained-glass window inside the chapel of the castellated Palace of Pena exhibiting Fernando II and the Convent of Our Lady of Pena on the left, and Manuel I and the Belém Tower on the right.

Fig. 8: View of the stained-glass window inside the chapel of the castellated Palace of Pena, Sintra (photograph provided by the author).

Fernando II nurtured a genuine admiration for Manuel I, with both of them being cultured people, lovers of history, and protectors of the national heritage, contributing to the stimulation of the arts while also being skillful politicians. Just as Manuel I had done about three centuries earlier, Fernando II sought to use architecture as an instrument of propaganda, power, and memory in order to strengthen the image of the Portuguese royal house as an effective ruler of Portugal and its overseas territories. So, the use of architectural references from the time of Manuel I was not only a cultural option, but also a political one, adopted by a king who wished to achieve the royal recognition of his people. He hoped that his castellated palace could be presented as a symbol of the union between the Royal House of Portugal and his own Germanic aristocracy.

Therefore, the architectural style considered by Fernando II to be the most representative of Portugal was precisely the one that came from the time of Manuel I, alluding directly to the nation’s glorious past and the heroic feats achieved in the golden era of the Portuguese Discoveries. This architectural style came to be known as Manueline (Manuelino), and its significance was widely discussed during the construction of the castellated Palace of Pena.

The recognition of manueline as the portuguese national style

The Manueline style16 began to be noted in the eighteenth century, mainly by foreign travelers who saw different characteristics in Portuguese late-medieval architecture when compared to that of contemporary buildings in non-Iberian countries. However, the aesthetic concepts and analytical instruments of architectural historiography were not sufficiently well developed or disseminated at that time, and therefore an erroneous perception of the Portuguese architecture from the time of Manuel I began to be repeated from at least the second half of the nineteenth century onwards.

In 1760, while searching for the Moorish roots of Gothic architecture, Thomas Pitt (1737-1793) visited the Jerónimos Monastery, already gaining a glimpse of Manueline architecture-even though he was still far from perceiving it as an autonomous Portuguese style. Pitt referred to the monastery, built at the orders of Manuel I, as having a different Gothic style from the English one-a peculiar style with an “air of the antique grotesque” and “resembling the Grecian” (quoted by Neto 2006: 109), perhaps intending to suggest a kind of Byzantine influence. Some years later, in 1777, William Dalrymple (1723-1814) described the existence of some works displaying a “Moorish taste” (Dalrymple 1777: 133) in the Unfinished Chapels of the Monastery of Saint Mary of the Victory (Mosteiro da Santa Maria da Vitória) in Batalha (better known as Batalha Monastery), leading him to attribute a Muslim origin to the Belém Tower (Dalrymple 1777: 142). In 1789, James Murphy (1760-1814) described the Unfinished Chapels, mentioning that “in some parts [it] is Arabian, in others absolute Gothic” (Murphy 1795: 42). As for the Jerónimos Monastery, Murphy referred to an architecture “compounded of the Norman-Gothic, and Arabian styles” with a cloister exhibiting “specimens of Arabesque ornaments” (Murphy 1795: 176).

Adam Neale (c. 1778-1832) repeated Murphy’s words in 1809 when referring to the “Arabesque Gothic” of the Unfinished Chapels (Neale 1809: 103) and the “singular Arabesque carvings” of the church of the Jerónimos Monastery (Neale 1809: 106-108). In 1820, William Graham referred to the “Moorish convent at Belem” as “one of the most beautiful Moresque, or Gothic pieces of architecture” (Graham 1820: 11), just as William Morgan Kinsey (1788-1851) did in 1829, in relation to the monasteries of Batalha and Jerónimos, also adding information about the Palace of Sintra, which “bears the character of Moorish architecture” in several parts (Kinsey 1829: 129). In 1835, James Edward Alexander (1803-1885) referred to the “mixture of Moorish and Gothic architecture” of the Jerónimos Monastery (Alexander 1835: 79) and the “pointed Moorish windows” of the Palace of Sintra (Alexander 1835: 233).

William Beckford (1760-1844) also considered the architecture from the time of Manuel I as having a strong Moorish influence: the “delicately-carved arabesque ornament” of the cloister of the Jerónimos Monastery (Beckford 1834: 56); the “Saxon crinklings and cranklings,” with “long and lanky marrow-spoon-shaped arches of the early Norman” and “Moorish horse-shoe-like deviations from beautiful curves” of the Unfinished Chapels of the Batalha Monastery (Beckford 1835: 136-137); and the Palace of Sintra was compared to the Alhambra and other Moorish buildings of Granada and Seville in a “fantastic oriental style” (Beckford 1834: 111-113). However, Beckford introduced a new influence coming from the East, when stating that the chapel of the Palace of Sintra had works that were similar to those of Eastern artists:

The low flat cupola, as well as the intersections of the arches, are a must in the style of a mosque, but the barbaric profusion of gold, and still more barbaric paintings [. . .] might almost be similar to the work of Singhalese or Hindustani artists, and reminded me of those subterraneous pagodas where his Satanic Majesty receives homage under the form of Gumputy or of Buddha. (Beckford 1834: 114)

All these travelers described these Manueline monuments as having a kind of Romanesque-Gothic style mixed with Moorish architecture, and their exoticism derived from the ancestral Muslim presence in Portugal. Pitt referred to a possible Byzantine similarity, and Beckford also added the Eastern influence, certainly because of the lengthy Portuguese presence in Asia. Foreign visitors were indeed able to distinguish a specific character of the Portuguese architecture from the time of Manuel I, which was different from that of other European countries, but the lack of conceptual instruments prevented them from recognizing it as an architectural style with its own intrinsic characteristics. The same can be said of the contemporaneous Portuguese writers, although they already mentioned some features which were characteristic of the Manueline style; for instance, António Castro e Sousa (1804-1876) described the Jerónimos Monastery as being of “Moorish or Arabian architecture” and having carved elements that decorated the building such as knots, crosses of the Order of Christ,17 armillary spheres, and the royal coat of arms, as well as some medallions with busts (Sousa 1837: 16, 27, 32).18

However, the debate about the existence of a Portuguese national style and the consequent recognition of the Manueline only began to take place more consistently at the beginning of the 1840s, being closely connected to a series of aspects associated with Portuguese Romanticism. It is well known that the idea of Portugal was a subject of major concern for Portuguese Romantics, which included its history, traditions, culture, art, and heritage. From the turn of the 1830s to the 1840s, all of these features were discussed more frequently among the most progressive Portuguese cultural elites, and Fernando II was at the very heart of the debate, sponsoring artists, protecting the Portuguese heritage, and interacting directly with the elites.

The restoration work undertaken by Fernando II, from 1839 onwards, at the small Convent of Our Lady of Pena was designed to respect the building’s architectural characteristics, establishing a kind of starting point for the debate about the existence of a Portuguese architectural style. Moreover, it also marked a subsequent association with the architecture from the time of Manuel I. This debate increased with the restoration work carried out at the Batalha Monastery, between 1840 and 1843, by Luís Mouzinho de Albuquerque (1792-1846), the Inspector General of the Public Construction Service, and at the Belém Tower in 1843-46 under the direction of the engineer Colonel António de Azevedo e Cunha (1810-1883), commissioned by António de Menezes Severim de Noronha (1792-1860), the Duke of Terceira. The repair work undertaken at the church of the Jerónimos Monastery and the Convent of Christ in Tomar during the 1840s can also be included in this debate. Fernando II was involved in all of these interventions-at the Convent of Our Lady of Pena, by restoring it, as well as at the Batalha Monastery, Belém Tower, Jerónimos Monastery, and Convent of Christ, by sponsoring the restoration and repair works (França 1990: 296).

In these particular cases, the restoration work was designed to achieve a conceptual, stylistic and constructive unity in the monuments, respecting the creations of their original authors. A stylistic reintegration in keeping with a predetermined image would recover the pristine style of these monuments and reestablish their initial splendor. Structures considered to be dissonant were removed as spurious elements, and damaged or missing structures were recovered, based on their analogies with similar elements that still existed there in good condition. However, restoration work was sometimes considered to offer a good opportunity for improving, enriching, and completing monuments, even if the new structures that were added to those monuments had never existed before.

The main questions raised by the technicians and those responsible for supervising the restoration of these monuments would have been as follows: if restoration work was supposed to respect the original style of monuments, what then would the original style have been in the case of the Convent of Our Lady of Pena, the Belém Tower, and the other monuments? What were the intrinsic characteristics of the architecture existing at the time of Manuel I that had to be respected? And which style(s) is/are represented by these monuments? As previously mentioned, certain particular features of the architecture at the time of Manuel I had already been detected by both foreign travelers and Portuguese authors, but the existence of a distinct architectural style only began to be recognized during the restoration work mentioned above, which involved the cultural elite and, of course, Fernando II.

The recognition of the Manueline style has been attributed to Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen (1816-1878), who was born in Brazil to a German father and a Portuguese mother. An article from 1840 shows that Varnhagen had already identified the specificity of the architecture from the time of Manuel I. He stated that the Belém Tower and the Jerónimos Monastery both exhibited the same architectural approach (Varnhagen 1840: 73-74). Just two years later, Varnhagen characterized the architecture of the Jerónimos Monastery in various articles published in the illustrated periodical O Panorama in 1842, later collecting his articles together in a single text. The “particular and sui generis style”-as Varnhagen described the Manueline style (Varnhagen 1842: 9)-was again identified by him, a year later, in another article about the Igreja de São Julião in Setúbal (Varnhagen 1843: 44).

Almeida Garrett sought to claim paternity of the recognition of the Manueline style. In the third edition of his poem Camões (1844), Garrett referred to the Jerónimos Monastery as a unique style, which “should perhaps be given the name of Manueline” (Garrett 1844: 220-221). However, this comment, inserted in an endnote (Nota L do Canto I), did not exist in the first edition (1825); it was, in fact, inserted in an endnote in the second edition of the poem (1839), but in a shorter version, and without the term Manueline.19 Nevertheless, Garrett was already aware of the specificity of the Manueline style when he referred to the Jerónimos Monastery as a “precious example of flowery Gothic” (Garrett 1839: 227). Later, Garrett referred to the Jerónimos Monastery as a building with “links to every kind of architecture, mixing Gothic traditions and Classical remnants, Romanesque simplicity and Moorish luxury,” but also as a place where a “specific national thought, an idea of greatness, elevation and enthusiasm” was represented (Garrett 1846a: 87-88). Moreover, in 1846, Garrett proposed the name Mozarab (Moçárabe) to classify the “special kind of national architecture” in which “the severe Christian thoughts of medieval architecture are made more relaxing” due to their contact with the “luxurious elegance of sensuous Moorish habits” (Garrett 1846b: 169).20

Mouzinho de Albuquerque published a report about the restoration of the Batalha Monastery carried out under his direction between 1840 and 1843, in which he stated that the Unfinished Chapels were not part of the same construction system or the same artistic way of thinking as the rest of the monastery. In fact, Albuquerque considered the Unfinished Chapels to belong to a transitional form of architecture, which later produced the Jerónimos Monastery. Albuquerque referred to this architecture as Emanueline (Emanuelina), having “isolated columns with low vaults, recalling the eastern palm trees almost parallel to the horizon”, in contrast to the Gothic style with its “bundles of columns supporting high vaults with pointed structures, recalling the multitude of fir and pine tree trunks from the northern regions” (Albuquerque 1854: 15-16). However, this report was only published in 1854.

Even the Polish diplomat Atanazy Raczyński (1788-1874) referred to the “architecture of King Emanuel” as being a specific Portuguese style with Gothic and Renaissance characteristics, complemented by Moorish reminiscences (Raczyński 1846: 408); Raczyński also cited Alexandre Herculano when stating that this architecture represented the “resistance of the Gothic style to the [Renaissance] style of François I [of France]” (Raczyński 1846: 331). The fact nonetheless remains that Varnhagen’s recognition of the Manueline style was credited to him by his fellow members, as can be seen in an article written by António da Silva Túlio (1818-1884) and published in 1842 (Túlio 1842: 541).

Acknowledging the person who first recognized (or, better, who first published details about) the Manueline style might not be the key point in this debate. In fact, several Portuguese intellectuals-such as Almeida Garrett, Adolfo Varnhagen, Alexandre Herculano, and Mouzinho de Albuquerque-were all writing at the same time about the architecture of the time of Manuel I as a national style, and it is very likely that they were engaged in an actual dialogue with one another. Fernando II also participated in this debate, not only due to his connections with this cultural elite, but also because of his involvement in the restoration and repair work undertaken at the Convent of Our Lady of Pena, the Belém Tower, the Batalha Monastery, the Jerónimos Monastery, and the Convent of Christ.

Garrett, Varnhagen, Herculano, and Albuquerque-and even the architect Possidónio da Silva, who was in charge of the initial repair work at the Convent of Our Lady of Pena, together with the Baron of Eschwege (Martins 2003: 62-63)-were part of the Lisbon cultural elite, and all of them lived abroad for either political or educational reasons, especially in France. The exile of these liberal Romantic intellectuals brought them into close contact with the leading liberal societies of that time, enabling them to absorb progressive thoughts that could then be transferred to the Portuguese reality-including their concerns about the country’s heritage. Their vision of the Portuguese heritage was thus broadened, due to their contacts with the heritage of other countries, enabling them to glimpse some of the specificities that existed in the national heritage, and therefore to debate the question of Manueline architecture as a national style. Ideas were certainly exchanged on this subject at some tertúlias (social gatherings with cultural overtones), which brought together these and other intellectuals and, most certainly, benefited from the participation of Fernando II.

The repair work undertaken at the Convent of Our Lady of Pena, the Jerónimos Monastery, and the Convent of Christ, and especially the restoration work at the Belém Tower and the Batalha Monastery, would also have been discussed at some tertúlias. Topics such as the establishment of the specific characteristics of architectural styles, and the best and most respectful approach to the repair and restoration of monuments, were certainly discussed by these intellectuals on several occasions during the first years of the 1840s.

The work undertaken at the Convent of Our Lady of Pena from 1839 onwards was initially quite modest, seeking to repair the humble monument while simultaneously showing respect for its stylistic characteristics. However, the intervention undertaken at the Batalha Monastery from 1840 onwards also called for a theoretical approach, not only because of its importance within the panorama of the Portuguese heritage and the sheer magnitude of the works that were carried out, but also because this monument was composed of parts from different periods and with different artistic languages. Thus, a knowledge of the main characteristics of each architectural language was essential in order to accomplish a successful restoration of the monument. The work undertaken by Mouzinho de Albuquerque was designed to restore the pristine appearance of the monument, harmoniously reproducing those parts of the building that had either vanished or been distorted, based on the study of the comparable elements that still remained in place, while also using similar materials and construction technologies. In this way, the authenticity of the monument would therefore be guaranteed. Nevertheless, the work undertaken at the Batalha Monastery was entirely focused on the Gothic structures.

Only the restoration work undertaken at the Belém Tower from 1843 onwards allowed for Albuquerque’s thoughts about restoration to be applied to a Manueline monument. As this was a major national monument, filled with symbolism and located at the main entrance to Lisbon from the ocean, this restoration work was designed to enhance the unitary image that was believed to have existed during the emblematic period of Manuel I’s reign and the Portuguese Discoveries. Once again, the debate about the Manueline style would have been fundamental for arriving at an idea of the pristine image of the Belém Tower, and the restoration work also became a kind of improvement work, searching for an idealized Manueline image. Structures from subsequent periods, or with little artistic value, were considered spurious and were demolished, clearing the monument of non-Manueline elements, while also inserting new ornamental elements with Manueline features, and thus increasing the monument’s characteristic Manueline appearance.

Choice of the Manueline Style for the Royal Castellated Palace of Pena

In view of all the above, it was logical that Fernando II should choose the Manueline style for the new castellated palace, which he wished to be seen as a Portuguese castle. Not only would the tertúlias and restoration work have contributed to Fernando II’s rejection of Eschwege’s neo-Gothic design, but his nationalist and historicist motivations caused him to prefer the Manueline architectural language. This option did, however, raise an important question relating to the debate about Manueline as the expression of a national architecture: how could Fernando II build a castellated palace in such a style?

The reign of Manuel I was an experimental period in terms of defensive fortifications, with the change from neurobalistics to pyrobalistics. Consequently, the forms and structures used in the construction of fortifications varied, depending on the technical development of poliorcetics. As, at that time, Portugal had a fully consolidated network of fortifications from the medieval period, Manuel I only ordered their modernization or complementation, adding some new fortified structures or reformulating the existing ones. In fact, the new Manueline fortifications were almost all scattered around the overseas territories of the Portuguese Empire. However, despite the fact that only a few Manueline fortifications had been built on Portuguese continental territory, there were some important examples to be found here - one of these fortifications served as the decisive inspiration for the conception of the castellated Palace of Pena. Fernando II certainly considered that the Belém Tower represented an excellent prototype for a Manueline castle.

Fig. 10, View of the Clock Tower of the Castellated Palace of Pena, Sintra. (Both photographs provided by the author.)

Fernando II would have been well aware of the debate that preceded the restoration of the Belém Tower and may therefore have allowed it to influence the construction of this monument. There are, in fact, clear signs of such an influence at the castellated Palace of Pena, especially in the clock tower with its bartizans21 and balconies, and the convex battlements adorned with crosses of the Order of Christ. The main gate of the castellated palace also had bartizans crowned by domes with buds, like the ones that can be seen on the Belém Tower. The attempt to conceive a neo-Manueline castle was also visible in the incorporation of architectural elements whose inspiration came from several Manueline monuments in the Portuguese Estremadura province, such as the Jerónimos Monastery, the Casa dos Bicos (the House of Facets), and the Palácio do Cunhal das Bolas-all of which are in Lisbon-as well as the Convent of Christ in Tomar and the Palace of Sintra (Branco 1986: 38-46). The compilation of Manueline elements was mixed with neo-Moorish, neo-Mudéjar, and Oriental (Indian and Chinese) elements during the construction of the castellated Palace of Pena, especially in its new wing.

The enormous cylindrical tower may also have been influenced by some Manueline buildings. In Eschwege’s initial design, this tower had been given a higher and more gracious outline with plenty of windows, some of which were balcony windows. However, the tower that was actually built is shorter and more robust, with fewer windows and with several floors clearly marked on its outside - possibly inspired by the castellated palace of Évoramonte, a building from the Manueline period. Even the twin turrets marking the Triton Arch22 may have been partly inspired by the buttresses of several Manueline buildings, such as, for instance the Manueline main façade of Guarda Cathedral. The influence of the Palace of Sintra on the new castellated Palace of Pena was also visible in the complex volumetry of the several structures built at different times, as well as in the use of tiles-namely the ones with armillary spheres (França 1990: 300)-and other ornamental stonework features, such as window frames and parapets.

The replica of the chapter house window of the Convent of Christ in Tomar23 is considered to be a major example of the bringing together of Manueline elements at the castellated Palace of Pena, in its attempt to acquire a Portuguese image. But Fernando II was passionate about the Middle Ages and its heroic knights,24 especially the Templar Knights-he was even photographed dressed as a Templar Knight. This may reinforce the explanation about the reproduction of the famous window of the Convent of Christ. The convent was the former headquarters of the Templars in Portugal (the Knights Templar were later replaced by the Order of Christ), so its symbolism was integrated into the new castellated Palace of Pena through the reproduction of this window.

Fig. 11: Chapter House Window at the Convent of Christ, Tomar; a modified replica of the window at the Castellated Palace of Pena, Sintra (photographs provided by the author).

As far as the former Manueline convent is concerned, most of its ground floor areas were conserved (chapter house, refectory, chapel), although some spaces between the dormitory cells on the first floor were eliminated and enlarged to form new rooms with new ribbed vaults (Schedel 2011: 77). The convent’s ancient clock tower was rebuilt in a different fashion, as mentioned before, and, on the opposite side of the convent, a two-story balcony was built, giving the impression of a Venetian Gothic loggia. The Venetian Gothic style was often considered by Northern Europeans to be somewhat exotic, possibly because of its supposed Byzantine influences.

Between the former convent and the new service building (kitchen, stables, and storage areas) was the New Palace (Palácio Novo), a rectangular edifice with neo-Manueline, neo-Mudéjar, neo-Mughal, and neo-Moorish features, which had a monumental cylindrical tower at its far end, opposite the convent. The service building displayed an Eastern revivalist influence of Moorish origin, and the Courtyard of Arches (Pátio dos Arcos) had a neo-Moorish arcade.25 Such a combination led to questions about the reasons for mixing Portuguese architectural elements with other features from foreign origins.

Fernando II and Eschwege were both foreigners in Portugal, and therefore their views about the Manueline style would inevitably be imbued with Germanic cultural references (or, rather, with the Germanic vision of the Manueline style and of Portuguese culture in general). For instance, in nineteenth-century travel literature, Portugal was considered by Northern European travelers to be an extremely conservative and religious country, still underdeveloped and heavily devoted to its ancestral traditions, as well as being marked by the earlier Muslim presence in the Iberian Peninsula and by contacts with Eastern and African cultures (because of its overseas empire), thus affording an aura of exoticism to the small country.26 The descriptions that travelers made of people, habits, traditions, lands, actions, arts, and other subjects expressed their point of view regarding their own cultures, which, in turn, decisively shaped the descriptions that they made of their experiences in the countries that they visited (Martins 1987: 17-20). Despite the fact that Portugal was the westernmost country in continental Europe, Northern Europeans were sometimes able to recognize oriental traces there, which were certainly influenced by the Orientalist fashions in vogue at that time.

Fig. 12: George Vivian / Louis Haghe, The Penha Convent, Sintra, 1839 (watercolor lithograph from the book by George Vivian, Scenery of Portugal & Spain).

Fig. 13: Castellated Palace of Pena, Sintra, Courtyard of Arches (photograph provided by the author).

It can therefore be inferred that, as foreigners, Fernando II and Eschwege would naturally develop their own particular vision of the Portuguese Manueline style,27 just as other Northern Europeans did at that time. For Fernando II and Eschwege, the Manueline style was seen as extremely ostentatious and exotic, artistically exuberant and richly ornamented, imbued with elements alluding to the sea and the Portuguese Discoveries, but also denoting strong Moorish influences, due to the ancestral Muslim presence in Portuguese territory before the Christian Reconquest, and because of the Portuguese conquests in Morocco.28 In this way, for them, the Oriental-and other-influences that were supposedly present in the Manueline style would not be just simply picturesque details, but also the result of contacts established with Asian, African, and even South American cultures, originating from the Portuguese overseas empire.

As a matter of fact, Paulo Varela Gomes mentioned that the Orientalism which Northern Europeans perceived in Iberian cultures was not misunderstood. In fact, they did not regard the East as a precise place, but rather as an idea of exotic delocalization outside Europe, be it in Asia, Africa, or even Oceania. In this way, it was naturally easy to blend architectural elements of cultures from North Africa, the Near East, the Far East, and other regions; some of those exotic influences were frequently attributed to the cultures of the Iberian Peninsula. The Orientalist influences attributed to Manueline architecture were not a Portuguese idealization, rather an idea derived from the eighteenth-century Orientalism that came from other European countries.29

Despite the developments in Portuguese intellectuals’ knowledge of the Manueline style, there still remained a misguided view of it in the minds of many European travelers who had visited Portugal. For instance, in 1846, the French historian Edgar Quinet (1803-1875) wrote about the Jerónimos Monastery:

It is still the house of God from the Middle Ages, but it is fitted out as if it were a ship prepared to sail. If one entered the cloister, the fruits and plants of several continents were innovatively revealed: coconuts, pineapples and peaches have been collected and added to the low-reliefs. [. . .] Here, Gothic mermaids swim in a sea of alabaster; there, climbing monkeys from the Ganges swing on the cables of the nave of Saint Peter’s church. Ostriches from Brazil flap their wings around the Golgotha cross. (Quinet 1846: 360-361)

As Paulo Pereira has already pointed out there are no coconuts, pineapples, peaches, monkeys, or even ostriches to be found in the monastery (nor are there any ostriches in Brazil). The main point of Quinet’s text is that the Portuguese Manueline architecture was perceived by Northern Europeans as being as exotic as the architecture of other eastern countries, such as India, Persia, or the Maghreb (Pereira 1995a: 53-60).

And the same thing happened with the words published in 1842 by the Polish Prince Felix Lichnowsky. As happened with other travelers, Lichnowsky referred to the Belém Tower and the Sintra Palace as having Moorish architecture(Lichnowsky 1845: 102, 127-130);30 but, in the case of the Jerónimos Monastery, besides being built in a “confused mixture of styles that were half Moorish-Byzantine and half Romanesque-Gothic,” its church had pillars with a “Moorish style, covered with the most extravagant low reliefs, reminiscent of the fantastic dreams of Pantagruel or the visions of Hoffmann. Naked children can be seen here riding dragons and violently opening the dragon’s mouths with their hands; beneath those animals are pairs of frogs hanging down, gripped by their tails” (Lichnowsky 1845: 98-100).

As can be easily seen, none of these features are to be found in the church of the Jerónimos Monastery. This description is simply part of the imagination of Lichnowsky, who saw the Manueline style as exotic and fantastic.

Returning to Fernando II, his appreciation of the Orientalist influences might also have been increased by the fact that he considered himself to have some traces of Asian blood, coming from his mother’s Magyar family (Schedel and Pereira 2016: 49).31 In a letter to his brother, Fernando II wrote that “in our case, we also have Hungarian, that is to say Asian, blood flowing in our veins” (Lopes 2013: 195). Therefore, most of the oriental influences found in the castellated Palace of Pena can be explained by all of these facts mentioned earlier.

Conclusion

In 1843, Fernando II wrote to his uncle Ernest I of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, saying that “once completed, the Castle of Pena will be the safest place in Portugal” (Ehrhardt 1998: 13). The Portuguese king was deeply imbued with Romantic influences, having a great fondness for the past, especially medieval times. Therefore, when he decided to build his new summer residence, he chose the form of a medieval castle for the new palace, just as his uncle Ernest I and many other Germanic aristocrats had done. The castellated Palace of Pena displays many different influences from Central Europe (and the United Kingdom).

Fig. 14: Casimir Leberthais, [D. Fernando II, Rei de Portugal], 1848 (lithograph from the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal).

On the other hand, with his foreign origins, Fernando II also felt the need to assert the power of the Portuguese royal family, which had been badly affected by previous historic events. This was another of his main motivations for building the castellated palace in Sintra: to symbolically state the monarchy’s authority in Portugal by constructing a royal castellated palace, since medieval castles had been closely linked to royal power. Moreover, in order to assert the Portugueseness of the royal family, the new castle would need to display an image that was itself based on Portuguese architectural characteristics. The language of Manueline architecture was therefore chosen as the preferred style, being reinvented at the castellated Palace of Pena in accordance with Fernando II and Eschwege’s own cultural visions. Consequently, the castellated Palace of Pena, together with the Belém Tower, the Batalha Convent, the Jerónimos Monastery, and the Convent of Christ, were all at the very heart of the debate that sought to define Manueline as the Portuguese national style.

The construction of the castellated Palace of Pena-the “Holy Grail castle, at the very top of the hill, overlooking the true Klingsor garden” (França 1990: 300), as mentioned by Richard Georg Strauss (1864-1949)-was nearly complete by 1865. The final result revealed a series of influences, pastiches, and reinterpretations of numerous architectural elements, as well as a hybrid architectural language that, far from being a disconnected and meaningless amalgam, resulted in a coherent building when viewed as a whole. The eclecticism of the castellated Palace of Pena assumed a paradigmatic role, serving as a catalyst of the neo-Manueline revival in Portugal, an architectural language inspired by the Manueline style. However, this neo-Manueline style turned out to be quite extravagant, with a profuse ornamentation of maritime, phytomorphic, oriental, and other elements considered to be associated with the time of Manuel I. The neo-Manueline style spread rapidly to various other architectural structures, from new residential buildings to churches, including town halls, pantheons, service buildings, memorials, exhibition pavilions, etc.32

In fact, during the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, the free and fantastical recreation of architectural shapes and forms from the past, applied without the rigid principles, technologies, or aesthetics that normally underlie each architectural style, offered the possibility of new and ingenious interpretations, emphasizing the aesthetic nature of certain visual effects and giving rise to an architecture that was frequently described as eclectic. The freedom that was afforded by such eclecticisms often resulted in the production of hybrid buildings.33 As far as civil architecture was concerned, in their efforts to assert their social status, the upper classes continued, in many cases, to adopt architectural forms based on medieval defensive structures, which they applied to their urban homes or summer residences. In some cases, it was possible to identify the persistence of a tradition linked to Portuguese rural manor houses (solares), where the existence of towers or battlements crowning such buildings was regarded as a symbol of social status.

It is interesting to note that, at the very same time as the castellated palace of Sintra was being built, another castellated palace was also being constructed close to Viana do Castelo. Portuzelo Castle was begun in 1853, later becoming the residence of the poet António Pereira da Cunha (1819-1890), who knew Almeida Garrett (Castilho 1893: 417) and was certainly aware of the debate that had been taking place about the Manueline style. Cunha’s new castellated house was full of neo-Gothic and neo-Manueline influences, and the Belém Tower was fully referenced in the tower of this house. The Barros Palace, in São João do Estoril, was built from 1896 onwards, in keeping with the design of the Italian architect Cesare Ianz (d. 1901); this castellated palace also displayed neo-Manueline influences that were closely linked to the Belém Tower, together with several other revivalist styles.

Fig. 15: [unknown author], Portugal - Bussaco - Palace Hotel (Estylo Manuelino), end of the nineteenth century (picture postcard).

But the most obvious case of the influence exerted by the castellated Palace of Pena on the expansion of neo-Manueline architecture was the construction of the Palace Hotel in the Serra do Buçaco (Mealhada), often referred to as the “Sintra of the North.” It had been intended that a royal palace should be built in Buçaco at the end of the nineteenth century, once again adapting a pre-existing and almost abandoned convent.34 However, the initial intentions were changed and, in 1888, the Italian architect, painter and set designer Luigi Manini (1848-1936) designed a project for the enlargement and remodeling of the ancient convent in order to serve as a hotel.

Manini was also inspired by several emblematic Manueline buildings, displaying influences from the castellated Palace of Pena and from the recognition of the Manueline style. The artist had indeed opted to associate several neo-Manueline elements with the building, despite the fact that the former convent did not have a Manueline origin. Once again, the Belém Tower in Lisbon was extensively cited, as can be seen in the shape of the hotel’s tower and its bartizans, battlements, and ornamental language. However, the final outcome, resulting from the contributions of Nicola Bigaglia (1841-1908) and Manuel Norte Júnior (1878-1962), deviated from Manini’s initial design-even if some visible resemblances had been maintained-giving rise to a building complex with an eclectic architectural language.

The castellated Palace of Pena served as the inspiration for a large number of revivalist castellated palaces in Portugal built by the aristocracy in the following decades in order to mark their social status, but also by the rich bourgeoisie eager to ascend to a higher social status.35 But the architectural style used in Fernando II’s castellated palace-the neo-Manueline aesthetics-not only became a source of inspiration for new buildings,36 but also had a major impact on the restoration of many monuments37 until the beginning of the twentieth century.