Introduction

The National Museum of Natural History and Science, Museums of the University of Lisbon (MUHNAC / Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência, Museus da Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal) houses a forgotten treasure: part of the scientific and working library of the Austrian physician and botanist Friedrich Martin Joseph Welwitsch (1806-1872). This library is a typical instance of those mentioned by Wells (1983: 17): “The libraries of a few famous and well-studied figures have been described: for example, Boyle and Ray. But many await their researchers, almost lost in card catalogues, in bibliographies and in neglected corners of library acquisition departments.”

Welwitsch’s links with Portugal started in 1839, when he should have been sent on an expedition to the Azores and other Atlantic islands through the Württemberg Botanical Travel Association, Unio Itineraria. However, the journey was repeatedly postponed due to adverse weather conditions, and, while waiting on the Portuguese mainland, Welwitsch undertook several botanical excursions around the outskirts of Lisbon. In 1853, he was sent by the Portuguese government on an expedition to the region known today as Angola. During this expedition, Iter Angolense (1853-1860), Welwitsch was the first European to describe the famous desert plant Welwitschia mirabilis (Dolezal 1974; Swinscow 1972; Edwards 1972). As a result of Iter Angolense, over 8,000 botanical collections were made, including around 5,000 species, of which about 1,000 were new to science (Dolezal 1974).

Welwitsch’s expedition to Angola coincided with a period of Portuguese history known as the Regeneração (Regeneration) (1851-1875), which affected the transition from an absolutist to a constitutional monarchy. In this process, Portuguese intellectuals increasingly promoted economic reforms aimed at stimulating social, economic, and technological development, and engaged in the economic, cultural, moral, and political renewal of Portuguese society (Catroga 1993; Machado 1998). The encouragement of scientific expeditions and travels, the creation of scientific academies and societies, and the profound reforms in education, particularly with regard to scientific and technological teaching, were measures taken to engage the country in the process of social and economic regeneration (Felismino, Tavares, and Carneiro 2016; Tavares 2017).

Welwitsch’s African collections became embroiled in a court case to determine which institution should receive the specimens (Stearn 1973). What triggered this action was Welwitsch’s will, signed on 17 October 1872, in which he expressed the wish that his collections should be deposited in the British Museum (hereafter referred to as BM) in London and at other herbaria (Albuquerque, Brummitt, and Figueiredo 2009). The Portuguese government, which had actually financed his Iter Angolense, was displeased and therefore demanded the return of the collections on 31 October 1872 (Stearn 1973: 102). As a result, there was a “complex legal dispute, which put the Portuguese Government, [later] represented by Joseph D. Hooker (1817-1911), Director at Kew, in opposition to the custodians of the collections in London” (Albuquerque, Brummitt, and Figueiredo 2009: 642). An agreement between the parties was eventually reached on 17 November 1875. Following this deal, the main set (called the “study set”) was returned to Lisbon (today housed at the MUHNAC, LISU Herbarium), the second-best set remained in London at the BM (today housed at in the Natural History Museum, London), while the remaining sets were sent to other institutions (Stearn 1973: 102).

This paper seeks to contribute to Welwitsch’s biography, although it does not claim to provide an all-encompassing biographical account. Instead, the aim is to use the genre of scientific biography to explore the international scientific network to which he belonged, based on the analysis of his private library, correspondence, and working notes. Scientific study is a collaborative effort, requiring extensive networks of expert or amateur scholars, whether operating on an institutional or personal basis. Essential in the construction of this narrative are the material objects, namely collections, instruments, letters, and books, among other sources (Podgorny 2013). Hence, a personal library represents much more than a mere assembly of books. Instead, because books are mostly accumulated as working tools, a personal library reveals research itineraries, “invisible colleges,” social interactions, academic and private interests, and so forth, and connecting people to books, and vice versa (Feisenberger 1966; Wells 1983; Wilkinson 1963; Sangwine 1978; Connor 1989; Pearson 2007; Buescu 2016). Moreover, correspondence has created and sustained national and international communities of scientists who exchange ideas and material while also sustaining personal ties of affection between collaborators in the scientific enterprise (Ogilvie 2006, 2016; Cooper 2007; Csiszar 2010).

Welwitsch’s will, scientific instruments, and library

In his will, Welwitsch mentioned that “[a]ll books, scientific instruments, Bats, Hierax, and other zoological objects [should go] to the Zoological Museum at Lisbon [Lisbon Polytechnic School, today MUHNAC]” (Gomes 1875: 15). Welwitsch’s books were considered “objects of scientific value.” His library was “perhaps [the] most complete collection of publications relating to tropical African botany in the possession of the testator [Welwitsch], and which [was] indispensable to the pursuit of his studies on the phytogeography of those regions” (Gomes 1875: 6).

The first batches of Welwitsch’s books, papers, and instruments reached Lisbon in 1876, and the last shipments arrived on 26 October 1879 (Tavares 1959: 341). It is not clear in which year the books arrived in Lisbon, although it is known that the library came accompanied by the botanical collections from Iter Angolense after the court case. The naturalist Bernardino António Gomes (1806-1877) and Francisco Manuel de Melo Breyner (1837-1903), the Count of Ficalho, drew up an inventory of the collections sent from London, registering natural history collections, papers, instruments, and books. Edmund Goeze (1838-1929), the head gardener at the Botanical Garden of the Lisbon Polytechnic School, who had earlier worked with Hooker at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, later presented the final version of this document (Tavares 1959: 341).

Very little is known about the scientific instruments. Their present whereabouts is still a mystery, but research continues. Some of them may never have been dispatched to Lisbon; for example, a microscope, later donated by the sister of the British mathematician and botanist William P. Hiern to the Linnean Society of London. According to Goeze’s list, at least two microscopes and one alcohol lamp were received by the Lisbon Polytechnic School, but there is no information about whether these are still to be found at MUHNAC. However, records show that Welwitsch acquired a significant number of instruments before going to Angola. A “List of Instruments,” probably drawn up when he went to London in 1851, included, among others, a sextant and an artificial horizon, a prismatic pocket compass, a pocket chronometer, a portable barometer, several kinds of thermometers, and a hygrometer. This list appears to be a “shopping list” and mentions the shops, addresses, and contacts that supplied these particular devices next to their names. Moreover, the portable barometer was mentioned in a letter from William Pamplin (1806-1899), a bookseller and a publisher of botanical works who acted as Welwitsch’s solicitor in London. The pocket glass magnifier, given to Welwitsch by Robert Brown (1773-1858) as a token of their friendship, and which he would proudly show to his visitors and colleagues, has also been lost (Dolezal 1974: 46).

Concerning Welwitsch’s library, according to Goeze’s inventory, 245 books and pamphlets were sent to Lisbon, of which, in 1944, 220 were recorded as still extant (Tavares 1959: 342; Dolezal 1974: 212). Most of these had been bought years before in London, prior to the Iter Angolense, via William Pamplin, who was also an agent for Unio Itineraria in London and responsible for handling the collections of subscriptions and the distribution of specimens (Swinscow 1972: 271). Only 198 could be found, while another forty-seven still remain to be found, according to the numbers in Goeze’s list. Most of these 198 books and scientific papers are preserved in the Botany Library of MUHNAC (LISU Herbarium).

The history of the MUHNAC libraries is full of twists and turns, but it may shed some light on several of the missing books. When it was created in 1837, the Lisbon Polytechnic School was organized into four main areas: a zoological and anthropological Museum, a mineralogical museum, a chemistry laboratory, and physics laboratories for the teaching of experimental subjects (Herculano 1841). Each section of the school had its own specialized library open to both students and teachers. In addition to making regular purchases of books and scientific periodicals, each library benefited from substantial donations on many occasions. Soon after its creation in 1837, the school received about 800 scientific books from Portuguese convents and religious orders (which were suppressed in Portugal in 1834). In 1858, it obtained the library (almost 300 volumes) of the former Royal Natural History Museum, created in 1765 in Ajuda, on the outskirts of Lisbon. In 1862, soon after the death of Pedro V (1837-1861), the king’s scientific library of nearly 400 volumes was transferred to the school from the Royal Natural History Museum of Necessidades (Felismino 2015; Felismino and Pereira 2017). On many occasions, former students, professors, and benefactors donated their libraries, either in their wills or during their lifetime. The procedure was always the same: books, magazines, and leaflets were sorted according to their scientific subjects.

When Welwitsch’s books arrived in Lisbon, the Botany Library was still a very recent creation. It had been established in 1875, shortly after the formation of a botanical garden at the Polytechnic School in 1873 (Tavares 1959). Welwitsch’s library went through the usual sorting procedure: books on botany and travel were sent to the Botany Library, while those from other fields were transferred to their respective libraries (Tavares 1959: 341-342). For this reason, Welwitsch’s books are now to be found in different libraries, such as the Zoology and Geology Libraries at MUHNAC. This was the inevitable fate befalling a polymath’s library in the modern times of specialization: it would be divided up and sent to different places, in accordance with more recent and stricter classifications of knowledge.

A terrible fire in March 1978 destroyed most of MUHNAC’s collections, but the Botany Library, which was located outside the main building, was not affected. Some of Welwitsch’s zoology and mineralogy books probably disappeared during this episode. Furthermore, taking into consideration the fact that MUHNAC is part of the University of Lisbon, it is very likely that some of his books are now to be found scattered among the different faculties of that institution (Felismino 2015).

Welwitch’s library

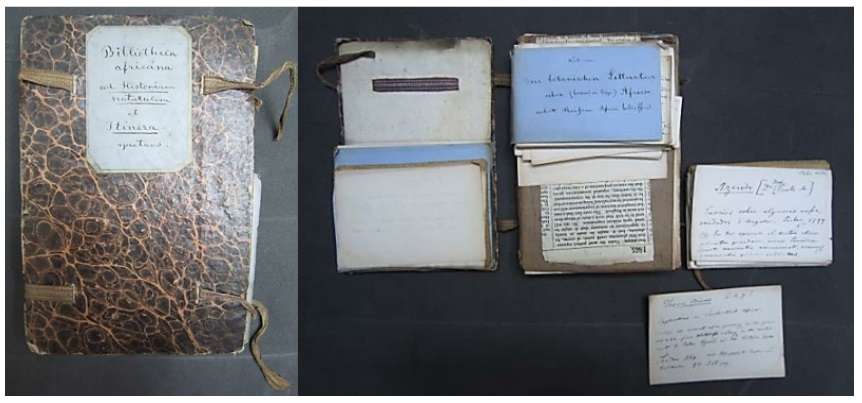

Most of Welwitsch’s 198 books contain personal annotations, references to his readings and exchanges, and, in some cases, the autographs of the authors, giving many clues and insights about his scientific network and thought. Some books were gifts from authors who were publishing about Welwitsch’s collections from Portugal (Berkeley 1853) and Angola (Reichenbach 1865; Reichenbach 1867; Hooker 1863). Another source that has proved to be a powerful instrument for understanding his scientific work as well as for searching for volumes, because it can provide clues, such as titles and authors, that may eventually lead to his still-missing books, is the Bibliotheca africana ad Historiam naturalem et Itinera spectans, a small “book wish list” or a notebook in which Welwitsch listed the references that belonged to his library (Fig. 1). This notebook also reveals Welwitsch’s scientific practices, showing how he organized himself in order to locate and consult a specific reference (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: “Bibliotheca africana ad Historiam naturalem et Itinera spectans.” (Source: Z MSS WEL, Library and Archives, NHM London)

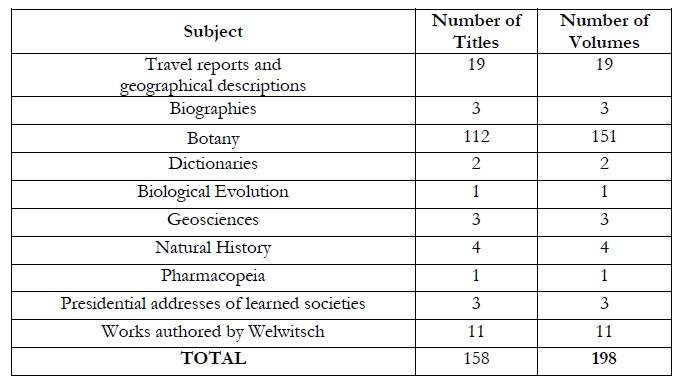

Welwitsch’s library of 198 volumes contains nineteen books consisting of travel reports, most of which relate to traveling in Africa and other similar biogeographical regions. It also has eight books on botanical gardens, three biographies-namely Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), Heinrich Wilhelm Schott (1794-1865), and Theophrastus (372 BC-287 BC)-besides eleven publications of his own. However, unsurprisingly, most of the volumes deal with botanical knowledge (Table 1).

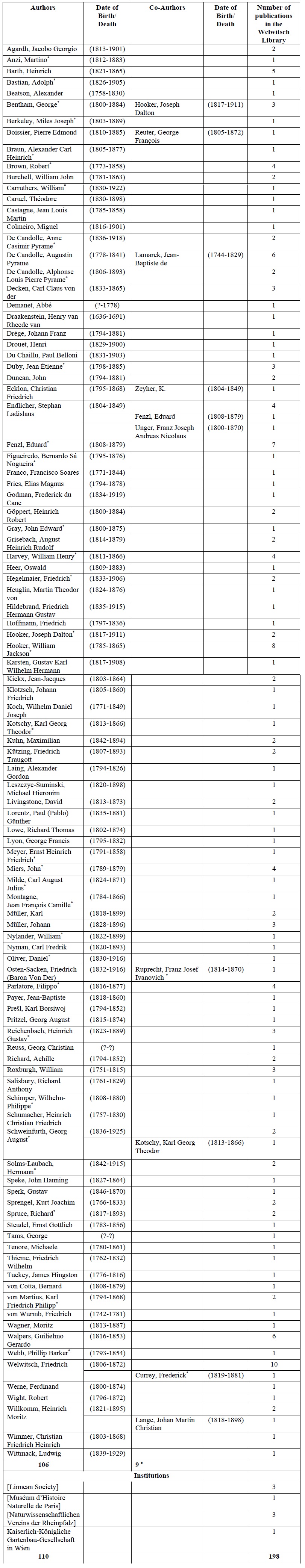

These 112 works were an essential part of his working tools, and we can find Florae, manuals, and catalogs ranging from general to specific topics. In this research, a total of 116 different authors are considered (including four institutions and six co-authors), and among these we find most of the renowned botanists and naturalists of his time (Table 2). Like many naturalists from that period, Welwitsch exchanged information in a variety of different ways: correspondence, specimens, publications, books, and objects (instruments and natural objects, for instance). Most of the books contain many of Welwitsch’s handwritten notes, which also provide relevant information relating to his scientific work and networks.

Welwitsch’s books, especially those concerning flora, show several records as well as codes, in which the botanist adds more information relating to the location and habitat of the species, in addition to other useful information. An example worth mentioning is the Lichenografia Europaea Reformata (Fries 1831), a publication that formed the basis for Welwitsch’s study on lichens (Tavares 1959: 337).

Fig. 2 Codes found in some of the books that belonged to Friedrich Welwitsch. The page shown is extracted from Lichenografia Europaea Reformata (Fries 1831).

In other situations, the codes seem to be revision codes, such as the notes that can be found in Plantae Tinneanae (Kotschy 1865). Theodor Kotschy (1813-1866) exchanged correspondence with Welwitsch, and, in one of the letters dated December 22, 1865, they examined the work Plantae Tinneanae (Edwards 1972: 297). This luxurious publication was also the subject of discussion between Welwitsch and Edward Fenzl (1808-1879), when Welwitsch sounded slightly ironic by mentioning that Kotschy’s work was too ostentatious and expensive (Dolezal 1974: 85; Willink 2011).

As far as Welwitsch’s own personal interests are concerned, his collection of books indicates a very complete and up-to-date bibliography of that period. As was to be expected, according to Goeze’s list, Welwitsch’s library included Über die Entstehung der Arten [On the Origin of Species] (Darwin 1859), which has unfortunately disappeared without a trace. However, other references to Darwin’s work can be found, such as Darwin’sche Theorie und das Migrationsgesetz der Organism (Wagner 1868). Considering that Welwitsch was preparing the expedition Iter Angolense before 1853, it is no surprise to find Instruction pour les voyageurs et pour les employés dans les colonies, sur la manière de recueillir, de conserver et d’envoyer les objets d’histoire naturelle ([Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris] 1845), a work containing instructions for travelers, with detailed suggestions for the observations and collections that they were expected to pursue.

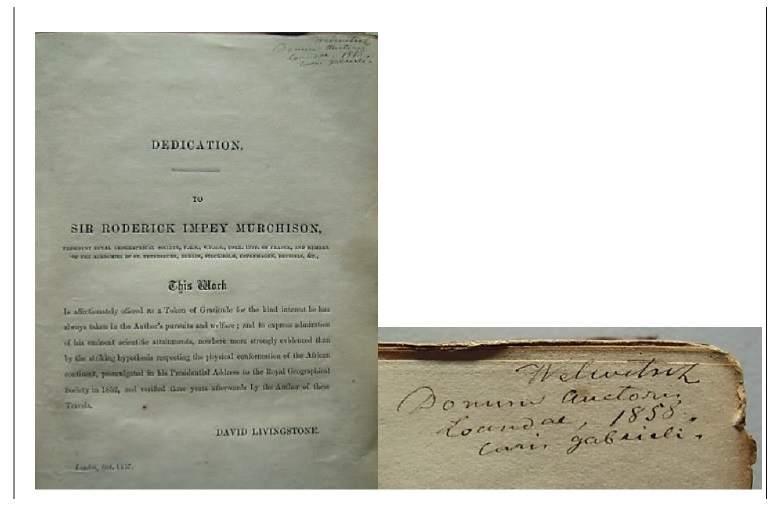

For instance, it is worth mentioning Travels in Western Africa in 1845 & 1846 (Duncan 1847), Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (Speke 1863), Reisen und Entdeckungen in Nord- Und Central-Africa (Barth 1857), Missionary Travels (Livingstone 1857), Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi (Livingstone 1865), and Catalogus Muscorum (Spruce 1867), among others. Therefore, Welwitsch’s library is not only valuable for its antiquity-most of the books are first editions, already constituting a precious treasure in itself-but also for Welwitsch’s many handwritten notes found in the books, which provide important information relating to his scientific work and network.

Moreover, his library reveals his vast knowledge of European and African flora, as well as from other parts of the globe, such as the flora of India (Roxburgh 1832; Wight 1834; Draakenstein 1839). Also related to the flora of India, we can find references in Welwitsch’s library to Hortus Malabaricus, a “standard reference work for the flora of southwestern India” (Draakenstein 1839; Raj 2016: 65).

In his notes, Welwitsch lists the Asian plants he had observed in the territories of Angola and Benguela (“Phytogeographia Angola, Plantae Asiaticae in territorio Angolae et Benguellae a me observatae”), such as Ficus religiosa L. and Tamarindus indica L., both of which were native to India and later introduced into Africa. In his study of the local vegetation, his knowledge also embraced the global. As already pointed out in a previous article (Albuquerque and Figueirôa 2018), Welwitsch shared a “Humboldtian scientific style,” in which the recognition of the interconnectedness of the flora and its particular environment was one of its new and important aspects.

Welwitsch’s scientific network through his library

By cross-referencing the names of the authors found in Welwitsch’s library with those of his correspondence, it can be seen that thirty-four of the 112 authors (authors and co-authors) exchanged correspondence with the Austrian botanist (Table 2). This fact reveals the existence of an active network through which Welwitsch did his best to keep up to date in the scientific field. By keeping this network active and busy, he remained alert to the most recent ideas and discoveries. Usually, the exchange of letters also resulted in the offer and exchange of books, as exemplified by the copies that were autographed by the authors and sent as gifts to Welwitsch. This was the case, for example, with Gray (1864), Salisbury (1866), de Candolle (1866), Missionary Travels by Livingstone (1857), and On Welwitschia by Hooker (1863), among others. It is worth noting that the authors with most publications in Welwitsch’s library are Edward Fenzl and William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865), with whom Welwitsch also actively exchanged correspondence. However, Fenzl is a particular case, for he was the only colleague from Welwitsch’s youth with whom he would later come to exchange mail (Dolezal 1974: 31). Taking into consideration that Fenzl was his most consistent correspondent and that they exchanged letters over a more extensive period, it is understandable why Welwitsch’s collection has more of Fenzl’s publications than all the other references in the library. The two Austrian botanists shared a great passion for their chosen subject of study. Nonetheless, their professional relationship never turned into a close friendship over the years, apparently because of Welwitsch’s difficult temperament (Dolezal 1974: 36). It seems that Welwitsch continued to exchange correspondence with Fenzl, not only because they shared intellectual interests, but mainly because his colleague represented the only way in which he could maintain his connection with Austria.

A good example of books considered as gifts is the first edition of Missionary Travels (Livingstone 1857), in which not only does Welwitsch’s signature appear, but also a note written by him in Latin-“Donum Auctoris, Loandae, 1858, Caris Gabrieli” (Fig. 3). This note reveals that the book was indeed a gift from the author, David Livingstone (1813-1873). However, Edmund Gabriel (1821-1862) was probably the person who delivered the book to Welwitsch in Luanda in 1858. Edmund Gabriel was a British administrator responsible for the suppression of the slave trade in Luanda (Bonner 1961: 38). Livingstone referred to Gabriel as “my much-esteemed friend Mr. Gabriel” and, in addition to his publications, he frequently mentioned his “friend Gabriel” in several contexts (Livingstone 1963: 162). On the other hand, Gabriel also belonged to Welwitsch’s network, as indicated not only by their correspondence (Edwards 1972: 296), but also by the botanist’s draft concerning the cultivation of cotton in Angola. This draft was delivered to the British administrator on 15 March 1858, before it was even published (Welwitsch 1859; Welwitsch 1875).

Fig. 3: From left to right: Livingstone’s Missionary Travels (1857) with a handwritten note by Friedrich Welwitsch (Luanda, 1858) at MUHNAC (LISU Herbarium)

Table 2: List of authors to be found in the Welwitsch Library

*Welwitsch’s correspondents, based on Edwards’ paper (1972) and Welwitsch’s address book at the LISU Herbarium (MUHNAC)

♦there is a total of six co-authors whose names do not appear as authors; the other three names are repeated because they published their works in partnership).

Conclusion

In this article, we undertook a contextualized examination of a library in order to consider its books as testimonies of a scientific career, a life that, with its ups and downs, evolved within a concrete, material reality, involving different people in the process.

By realizing which works belonged to Welwitsch’s personal library, we can form an impression of Welwitsch’s universe, his network, his interlocutors, the references that he found relevant, and the science that he valued. We agree with Pearson (2007: 4) when he states, “The history of libraries and book ownership, and the formation of collections, is an important part of this, as it provides a window into earlier tastes and fashions, and allows us to see not just what was printed, but what people bought and put on their shelves. Both individually and collectively, books offer a wealth of historical evidence to help us to understand their impact and influence.”

Welwitsch’s library therefore indicates that he was a well-connected botanist, and, although he was not in touch with all of his fellow contemporaries, he was nonetheless aware of their work, and vice versa. Being an influential scientist was a powerful tool for knowing what had been done, developed, and discovered by others: “one crucial strategy was simply to ask the advice of those most likely to be familiar with the field in question” (Csiszar 2010: 408). Because of his attitudes in the past, it was possible for us in the present to form a clear notion of the science of that period and understand its context. The practices of naturalists in the past involved a set of attitudes and strategies that, although they may still remain largely unexplored, constitute an important field of study for historians of modern science, as Csiszar reminds us (2010: 399):

The methods used by Darwin and his contemporaries for locating relevant print sources were-as they would continue to be-varied, complex, and often serendipitous; they might sometimes involve consulting indexes and catalogs, but they also included trawling the contents of serials and titles of monographs on the shelves of personal and institutional libraries, following the trail of footnotes and lists of references, and (perhaps most importantly) corresponding with colleagues, booksellers, and friends for guidance, new leads, and off-the-cuff reviews.

In Welwitsch’s case, the notebook entitled “Bibliotheca africana ad Historiam naturalem et Itinera spectans,” filled with loose notes and newspaper clippings, seems to reveal the method used by the botanist to locate his library references. Welwitsch’s library was closely linked to his work, revealing itself primarily as the working library of someone whose interests were not restricted to botany, but who was instead an all-encompassing naturalist. Although his own specific field is indisputably dominant, Welwitsch brought together knowledge from other scientific areas, according to his nineteenth-century Humboldtian profile. At the same time, the comprehensive nature of Welwitsch’s interests also highlights the botanist’s intention to produce a vast and impactful work about an important region of the globe at the center of a colonial dispute in his time.

Welwitsch’s library allows us to see beyond his network of correspondents. It also enables us to fill in the blank spaces. Through Welwitsch’s library, it is possible to build up the various layers of his contacts, adding even more connections to his well-established network. One remarkable example is Charles Darwin. Although they did not correspond directly, the correspondence between Darwin and J. D. Hooker made references to Welwitsch’s work, such as the discovery of Welwitschia: “I have looked in Lindley about Gnetum; what a curious form your new one must be,-what a fine living fossil, preserved from past times.”

Welwitsch’s library reveals itself to be a most valuable asset for the study of science, botany, and heritage. Welwitsch’s handwritten notes in each book-marginalia-should be analyzed in detail, although this is a task that lies beyond the scope of the present article.