Between 1481 and the first half of the eighteenth century, the Portuguese Crown created various mechanisms of sustainability and administration, which were designed to overcome the challenges arising from the relationship that it had established with the sea. The problems to be solved were manifold, mainly consisting of piracy and smuggling, which called for the reinforcement of the Crown’s naval defense. On the other hand, there was a shortage of manpower needed to serve as the crews of naval fleets. The high risks involved, together with the potential danger of losing vessels, which maritime activities necessarily entailed, made the naval profession unattractive to seafarers and led them to avoid such positions.

In order to enhance the value and dignity of maritime careers, the Crown worked hard to create a standardized professional structure in keeping with the ones already established for other professional groups. Not only did this require the production of a regulatory legislative framework, but also a general registration system in order to ascertain whom to recruit for the crews and from where they were to come. Other systematizing measures were introduced for the recruitment, training, and support of these men to ensure that this workforce would be available whenever needed. The central power’s dependency on the initiative of private individuals was evident, since the sustainability of trade routes and the country’s naval defense hinged on the success of these enterprises.

During this period, the Crown was obliged to play an interventive and controlling role, promoting the maritime career and enhancing the skills of seafarers by granting them social and professional privileges that would attract them to these jobs, but also punishing them for any misdemeanors. The censuses, recruitments, examinations, accreditations, and remunerations of careers coordinated by the Crown placed seafarers under royal jurisdiction, which could result in their being rewarded with knighthoods or the title of fidalgo2 or squire.

It is against this general backdrop that we understand the evolution of the legislative and normative framework developed by the Crown for the profession of seamanship. This is the context on which I shall focus our attention, in order to discuss not only how the Crown acted, but also how private agents negotiated with and exerted pressure on it. In this article, we set out to discuss and explore the relationship between the Crown and these seafarers, who are considered here as private individuals, given their socio-professional characteristics.3 By referring to documents written by the king, such as official letters, royal charters, and letters of grace and privilege, I will attempt to understand the nature of the relationship that existed between the central and private powers.

The central power and seamanship: common rules (1591 and 1626)

The mechanisms of action devised by the central power and its formal institutions were instrumental in the creation and consolidation of the nation’s overseas empire, but such expansion always required the provision of assistance to individuals through a series of cooperation networks. Consequently, a parallel analysis of these networks is essential, as they were equally fundamental for the achievement of the intended objectives (Polónia and Barros 2015: 243-273).

The term “seafarer” was used to characterize those individuals whose professions were in some way related to the sea, whether they worked on land or aboard a vessel, for they could be either navigation officers or shipyard officers, depending on what was stipulated in the regulations of 1591 and 1626.4 The Portuguese Crown sought to control this socio-professional group and standardize their functions, responsibilities, and training. To this end, two separate sets of regulations were drawn up: the regulations of 1591 and those of 1626. More than merely establishing rules, these statutes were designed to control this group at all levels. The scarcity of human resources to serve on the royal fleets justified the creation of both the 1591 and the 1626 regulations, since it was necessary to defend ships against enemies and corsairs. At a time when other maritime powers were also seeking to dominate overseas territories, the available human resources were limited, since seafarers preferred to dedicate themselves to their own private business, as this was much more profitable and advantageous than serving in the king’s fleets (Costa 1989: 99-100; Oliveira 2017: 49). Both sets of statutes contained similar structuring measures in terms of censuses, recruitment, training, benefits, hierarchy, and obligations-albeit with minor differences that distinguished one from another, in keeping with the specific needs of the time.

The first measure established by these documents was the registration of navigation officers-firstly at a local level through a census conducted at each port, from Caminha to Sines, and then secondly at a more general level in a ledger kept at the Royal Warehouses. Pilots, masters, sailors, cabin boys, and other navigation officers between the ages of eighteen and sixty were submitted to this census in which their names were registered-along with those of their wives (when married) or their parents (when single). Each registration corresponded to a single page of the ledger, which took the form of a service record, with additional information also being added for each registered professional about their years of service, the locations and types of vessels on which they served, whether tall ships or barques, as would be established by the 1626 regulations. The goal of compiling all this information was to determine the precise qualities of each officer, since these registrations were a crucial means for conducting recruitments whenever necessary (Costa 1989: 99-100; Oliveira 2017: 117-126). The records were updated on December 1 every year at each port. The names of those who had died during that period, or who had already reached the age of 60 or over, were crossed out, and the names of the new men were added. The new lists were then sent to Lisbon in order to update the general register.

The caulkers and carpenters of the realm were subjected to an identical system of registration. Those men between the ages of twelve and sixty who worked in shipyards were registered in Lisbon, the Ribatejo region, and the regions to the south of the Tagus River. Their registrations also included the details of their sons and servants so that they could similarly learn their craft.

The 1626 regulations introduced a new craft into the professional category of seafarers, which had previously been omitted due to the standardization of other occupations. The important role of shrouds in shipbuilding meant that it was necessary to reduce the importation of materials of inferior quality and to increase the respective domestic production. This led King Filipe III to decree the registration of ropemakers, with special attention being given to the districts of Santarém, Torre de Moncorvo, and Coimbra, as these were the main centers of rope production in Portugal. Each registration required a declaration of the ropemaker’s proficiency in the art of estovar, twisting and spinning, as well as of their masters’ names. This information would subsequently be added to the general register.

Unlike the other crafts of seamanship, the registration of gunners was carried out over a wider geographic area, especially in Africa and India. In each territory, a list of gunners was compiled and then sent to Lisbon to be added to the general register, kept at the Royal Warehouses as was also the case with the other crafts. Such registration was undertaken through an examination of these individuals (Costa 1989: 104, 117).

The census of seamen was motivated by a single purpose-to know who they were, how many there were, and where could they be found to make it easier for the Portuguese Crown to recruit them whenever this was considered necessary.

The recruiting of navigation officers was conducted with an underlying sense of equity to ensure that men from different regions-and not from just one area-were called into service. Hence, those who had served in the royal fleets during a given year would not be called up in the next one. Rather than benefiting every one of these professionals, this directive was intended to penalize everyone equally.

The Crown wished to guarantee an equal balance in relation to the places where seafarers were called upon to perform their duties: those who served on the trade routes to India, Malacca, and Mina would be placed in the service of the naval fleets in the following year, and vice-versa. However, since the number of those serving in the armadas was greater than the numbers needed for the shipping routes, a surplus list was compiled-those who found their names on this list would have to wait for a year before they embarked (Costa 1989: 102). By implementing this rule, the central powers ensured that the Portuguese naval fleets did not lack manpower-even though service on the shipping routes to India, Malacca, and Mina was considered, by far, to be the most attractive and profitable of the two jobs. The Crown therefore took into account the personal motives of those involved in the recruitment policies, who used them (manpower) as an implicit bargaining factor.

The same situation arose in the case of permission to undertake voyages in the service of private parties for those who were not drafted into the royal fleets-not only were these individuals limited by several predefined rules, but they were also tasked with passing on their knowledge of their crafts to their sons, to orphans, and to those abandoned by their relatives. In order to maximize learning experiences, the 1591 regulations also allowed for ten-year-old boys to embark on ships accompanied by their masters-usually their fathers. The masters and sailors were tasked with taking under their wings one or two of most talented boys and teaching them the art of piloting, hence granting them the rank of second pilots or advisors. The 1626 regulations also stated that, in addition to assisting the pilots, the boys should engage in charting and the taking of sun sightings. To further encourage them to learn this profession, this statute also ordered that the young pupils were to be granted a salary and daily rations, just like the rest of the officers onboard the vessel (Costa 1989: 103, 114).

Both the 1591 and 1626 regulations were drawn up in the context of a serious crisis and dire necessity in which the activities relating to navigation were not appealing enough on their own to guarantee the necessary voluntary enlistment. The 1591 regulations introduced a novelty: the creation of a certified professional workforce that would be sufficient to meet the nation’s requirements. As we can see, however, when analyzing some of the directives arising from the 1626 regulations, this situation had already become more complex.

The damage caused by privateers and the shortage of seamen were the main reasons behind the creation of the 1626 regulations, which reiterated some of the guidelines already included in the 1591 regulations-these guidelines underwent a process of bureaucratization5 involving the introduction of heavy sanctions for those who disregarded mandatory conscription or avoided it altogether. In fact, this directive seems to indicate that evading the draft was common practice at that time. The ombudsman and the officers of the Royal Warehouses were extremely careful in their choice of individuals to serve on the royal fleets-the detailed registration records largely contributed to this cautious selection process. The sanctions were harsh and involved severe cuts being made to seafarers’ salaries, a four-year exile in Africa, and the revocation of all their privileges as well as the right to practice their craft (Costa 1989: 109-110).

With the 1626 regulations, an attempt was made to standardize the empirical knowledge that had been gained about navigation, although the regulations governing the kingdom’s main cosmographer,6 introduced in 1592, were already in place for this very purpose (Polónia 2007a, vol. I: 416-417; Matos 1999; Costa 1989). This statute ordered that all navigation officers must be well trained in their activities. “And because there is a severe shortage of experienced pilots to sail the Indian route,” as was stated in the 1626 regulations, pilots would have to be extremely well qualified and, preferably, men who had been trained solely to be sailors from a young age (Costa 1989: 114).7 The position of pilot would therefore be barred to ropemakers, guardians, and petty officers overseeing the naus bound for and arriving from India, as well as individuals who were inexperienced in the arts of charting and sun sighting. And masters were tested in the activity of piloting, with their examinations covering the very same parameters as those undertaken by pilots.

The ten most experienced sailors served on the Indian route. They took with them astrolabes, nautical charts, and additional instruments essential for piloting the vessels. According to the regulations, these individuals were required to take daily sun sightings, draw up charts, elaborate routes after sun sighting, and share all this information with the pilot. The latter would listen to them and give them instructions. This particular clause of the regulations established paths for the empirical training of sailors. Such training was based on personal experience-rather than consisting of the institutional transmission of knowledge-and provided a way for seafarers to progress in their careers.

In addition to underlining the need for an in-depth knowledge of the art of navigation, the 1626 regulations established a certain type of theoretical training, which took the form of lectures given by the main cosmographer (mathematics classes) and were designed to improve their navigation skills. These classes were already provided for in the 1592 regulations (Matos 1999: 62). The main cosmographer would issue certificates to those attending his lessons, indicating all the lessons that they had attended (Costa 1989: 115-116).

The gunners were also subject to these new educational reforms. They were now examined both on land-at a location chosen by the Steward-and at sea, where their skills were assessed by the Ombudsman of the Royal Warehouses, the clerk in charge of the general register, the Keeper of Gunpowder, the Chief Constable, the man in charge of the mathematical lessons,8 and two foreign constables from Flanders.

The central powers and seafarers: legislative production (1481-1640)

The sea and the relationship that was established with it diversified the social roles and consequent social strata:

For some, it was a source of modest livelihood; for others, for those who understood the work taking place in shipyards, it was a source of great profit; for the monarch, it was a new scenario for his power strategy. Pilots, masters, shipowners, landlords, and merchants: a wide range of social roles that invite us to be aware of the equally diverse ties that unite men and ships. (Costa 1997:10-11, my translation)

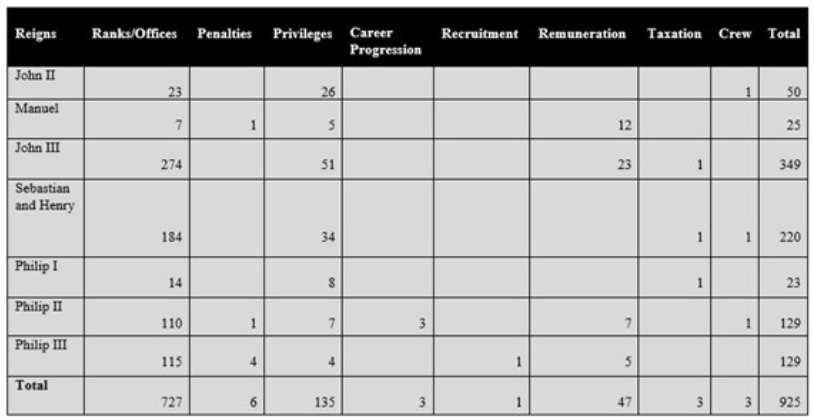

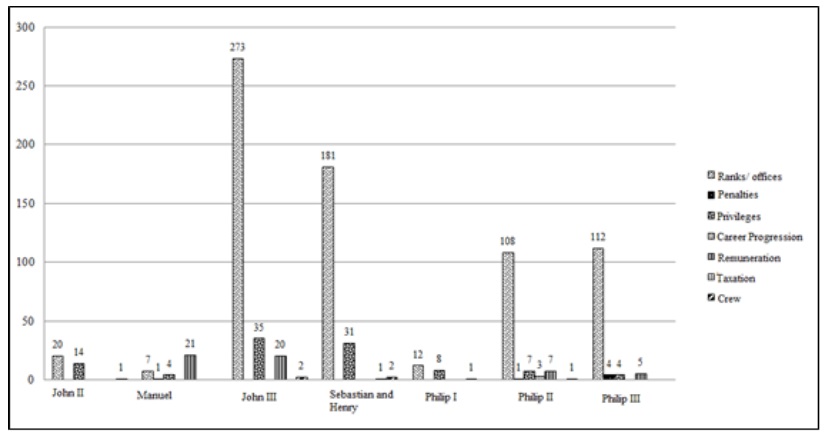

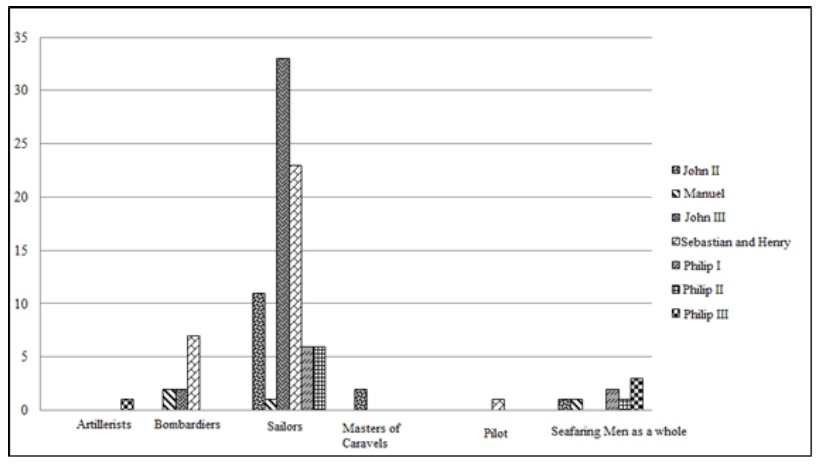

The legislative production relating to seafarers revealed several indicators that supported the existence of an effective naval policy, put into effect by the central powers. Nevertheless, the Crown’s legislative production on these matters mainly focused on bestowing ranks and offices and granting privileges, with a total of 925 registrations. During the reign of João III,9 349 official orders were composed, the largest from the eight reigns analyzed, which were mainly letters of service. João III’s successors continued to pursue a similar policy, with 501 registrations-and we should highlight here the results obtained for the reigns of Sebastião and Cardinal-King Henrique,10 Filipe II and Filipe III (Table 1, Fig. 1, and Fig. 2).

The Portuguese Crown was significantly concerned with the regulation of positions and crafts, as evidenced by the 727 registered documents (713 for navigation officers, and fourteen for shipyard officers, respectively). Its main purpose was the normalization and control of a socio-professional group-a group on which the Crown relied heavily-by means of royal pardons, royal letters, service letters, permits, and regulations. As we saw earlier, it was through these regulations that the central powers created a structure for the tasks of a craft, indicating its required competences and functions, which were, a posteriori, updated by subsequent royal letters or permits when necessary. The elaboration of royal letters, provisions, laws, and permits clearly revealed the failure to comply with the measures stipulated in the statutes,11 which, in turn, led to the creation of new rules.

By analyzing the promulgated letters to the navigation officers, we can see that the issues relating to defense and increasing administrative demands were the reasons behind these attributions, and, in this way, the gunners and captains stood out from the rest of the group. The predominance of deliberations relating to these positions was in line with a policy that sought to defend the vessels themselves and to ensure that the seas remained navigable. The administrative needs and challenges called for a diachronic expansion of the existing offices and officers, which is confirmed by the number of letters of service. Several roles never ceased to exist, such as those of gunner, captain, fleet captain, seafarer, and chief pilot, while others were only to be found during the reign of a certain monarch or for a short period of time, such as the military roles “captain of the fleet’s infantry” (during the reign of Filipe III) or “captain general of the galleys of the kingdom” (an active post during the period of Iberian Union) (Oliveira 2017: 117-119).

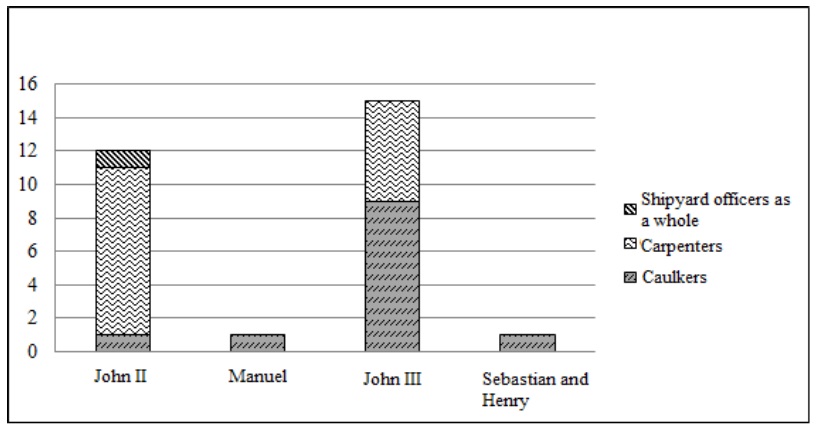

In the case of the shipyard officers, we were only able to find nine documents-three pertaining to the reign of João III, three to the reigns of Sebastião and Cardinal-King Henrique, and one for each reign of Philippine Dynasty. At a structural level, the group of shipyard officers was not subjected to any major change in terms of the officers who belonged to it, although there was an increase in terms of the legislation aimed at the highest hierarchy of shipbuilders (shipyard masters and shipyard supervisors) during the Philippine Dynasty, as opposed to the reign of João III, during which the legislation was aimed essentially at the master caulkers and master carpenters. A policy of bureaucratization and the increasing complexity of the shipbuilding processes-to cater to increasingly demanding orders-may be the justification for these events (Oliveira 2017: 96-97).

One of the ways of guaranteeing an available workforce to meet the needs and requirements of the Crown was through the granting of privileges and exemptions (Polónia 2007a and 2007b; Barros 2016; Moreira 1995; Costa 1997). In the case of the navigation officers, if they avoided service in the fleets, this would result in a lack of technical staff for the vessels’ crews, which justified the granting of privileges to this group. By resorting to these measures, the Crown ensured the recruitment and the continued functioning of the maritime enterprise, both on land-by the shipbuilders-and at sea. On some occasions, the recruitment could be mandatory, a process dubbed as apenamento,12 in order to complete the fleets. By royal decree, sent to all ports of the realm, the seafarers were obliged to comply with the Crown’s orders or else they would be subjected to various punishments (Polónia 2007a, vol. I: 324-327; Costa 1994: 40).

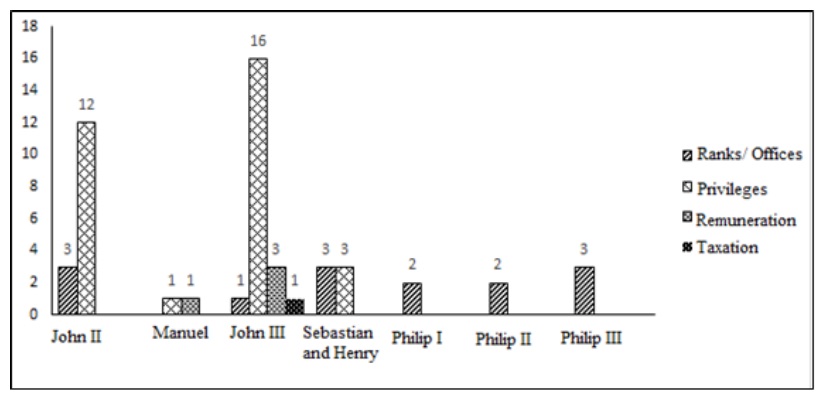

Between 1481 and 1640, the Portuguese Crown granted about 125 privileges, 103 of which were given to navigation officers and 29 to shipyard officers, privileges that granted this socio-professional group unequal benefits. The granting of letters of privilege was not a new practice during the period under analysis, since the granting of privileges dated back to the medieval period. However, it was a consequence and a reflection of the need to provide incentives to attract qualified manpower during troubled times (Costa 1994: 39-44; Polónia 2007a, vol. I: 418).

As mentioned above, the shipyard officers received 29 letters of privilege-sixteen to carpenters, twelve to caulkers, and only one13 for this group as a whole. João II and João III were the monarchs who most favored the shipyard officers, granting them a variety of privileges (Fig. 3).

The abundant production of letters of privilege during João II’s reign can be explained by the fact that, at that time, shipbuilding efforts were being promoted, due to a shortage of vessels to be used for discovery purposes and the consolidation of new trading relations, together with a policy of socially promoting the professional groups through rewards, privileges, and exemptions. During João III’s reign, however, the figures obtained seem to confirm a tendency for an abundant legislative production that focused mainly on naval logistics-an aspect that characterized the king’s administration. On the other hand, the increasing acts of privateering and piracy against the Crown’s property and dominions and the demands of an ever-growing Empire-namely the king’s rekindled interest in Brazil-were other factors that may have justified the monarch’s focus on granting privileges to professionals working in the field of naval logistics (Fig. 4).

As far as the letters of privilege granted to navigation officers are concerned, most of these were granted to seafarers. João II, João III, and Sebastião and Cardinal-King Henrique either granted or confirmed a large number of letters of privileges to these officers. During periods when maritime activity was an attractive proposition, the granting of privileges was not necessary-the reign of Manuel I is a prime example of this. On the other hand, once the appeal had begun to wane, it became necessary to captivate sailors-and it was this reality that led the Philippine Dynasty to conceive the regulations of 1591 and 1626. Indeed, the granting of privileges was in keeping with contexts in which there was a shortage of individuals to man the crews of the royal fleets, as seen during the reigns of João II (in which a period of new discovery enterprises and the consolidation of new trading relations required men to fuel these intentions) and João III (due to issues relating to the nation’s defense, which stemmed from frequent conflicts that challenged the large Portuguese maritime presence) (Oliveira 2017: 127-129).

The privileges granted to seafarers are well-known. Exemption from military service, the payment of municipal taxes, and municipal responsibilities were just some of those privileges, together with exemption from the payment of taxes on retirement pensions, among others (Costa 1994: 40; Moreira 1995: 57-58; Boxer 2012: 216). The 1591 and 1626 regulations stipulated that pilots, masters, other officers, gunners, caulkers, and carpenters could bring rolls of silk with them as a privilege when they served on the routes to India, Malacca, and Mina. The 1626 regulations stated that gunners were exempted from serving in the special military units known as terços, from accommodating soldiers in their houses, and from accompanying prisoners. The highly trained nomina gunners enjoyed a contract of exclusivity with the Crown and its representatives due to a charter dating from 1506, therefore effectively ending their role as intermediary agents in the recruitment process and guaranteeing the king their service, through a contract between the individual and the monarch. When the services of these men were required outside the city, they were granted financial support, a measure that was later extended by the regulations to carpenters and caulkers whose services were required in Lisbon-those who lived outside the city limits were paid for the days that they spent travelling to Lisbon. They were granted specific permits that allowed them to carry weapons by day and by night-a measure that was already described in 1498 and confirmed in 1526 but had previously been limited to foreign gunners residing in Lisbon. Among other privileges, they could not be flogged in public, nor could they be sentenced to the gallows if they were convicted of any crime, and they were exempt from helping with public works or maintenance (Costa 1989: 106, 121; Castro 2013: 2-8). The carpenters and caulkers from Lisbon were also free from serving in the terço regiments and were granted permission to enlist in private endeavors, as were the masters, pilots, and the remaining navigation officers.

In 1424, 1426, and 1429, João I decreed several privileges for the carpenters and caulkers of Lisbon-privileges which were later confirmed by Manuel I14 and served to justify the demand that these same privileges be extended to the rest of the shipyard officers of the realm. In 1426, confirming the privileges granted by his predecessor, Fernando I, João I decreed by royal charter that the carpenters and caulkers of Lisbon were to be granted exemption from paying a tax on their daily wage15 to the weights and measures inspector.16 A previous charter from 1424 had already freed them from serving against their will-by night or by day, on Sundays, or on holy days-when they were working in shipyards. From 1429 onwards, they were exempted from paying taxes on their retirement pensions and from giving clothes, and were permitted to bear weapons either by day or by night (Cruz 1983: 167).

New resolutions, taken in 1503 and confirmed in 1530, granted the carpenters of Lisbon exemption from working on the construction of bridges, walls, fountains, cobbled streets, or footpaths-unless these were part of their properties-as well as exemption from punishment by flogging and from being sentenced to the gallows. These privileges, like the ones mentioned previously, were demanded by the shipyard officers of Porto from the monarchs-both Manuel I17 in 1497 and João III18 in 1538.

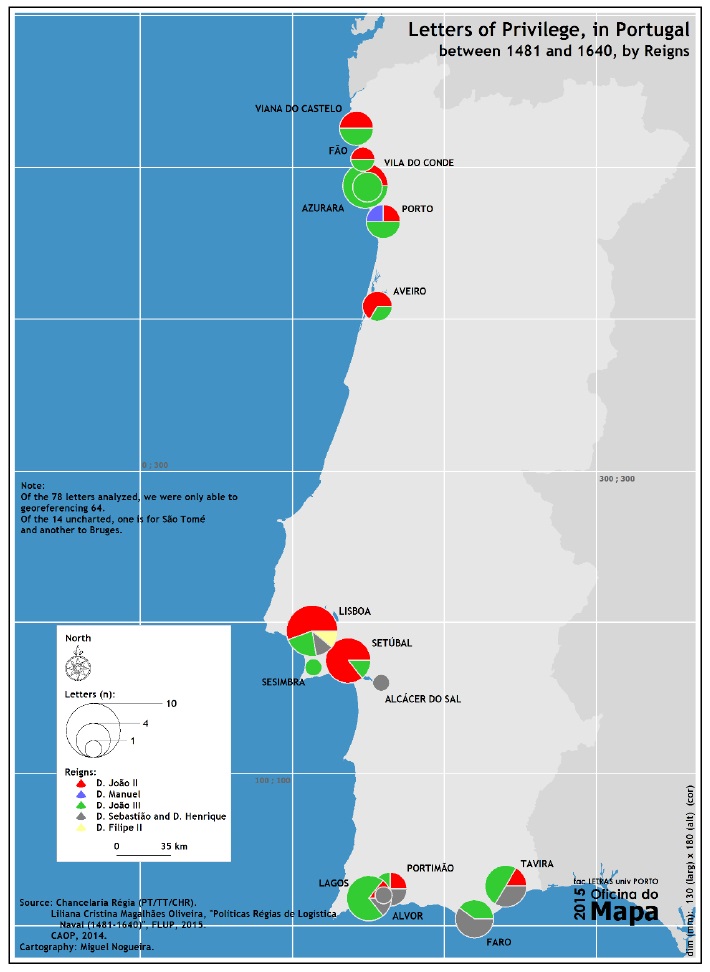

The letters of privilege granted to shipyard officers as a group were mainly addressed to the maritime communities in the north of Portugal. And, although there are records of similar letters being granted to navigation officers in the north, the majority of the privileges granted to navigation officers were concentrated in the south, as shown by the following maps (Map 1 and Map 2).

Source: Oliveira (2017: 178)

Map 1 Letters of privilege in Portugal between 1481 and 1640, by categories

Source: Oliveira (2017: 179)

Map 2 Letters of privilege in Portugal between 1481 and 1640, by reigns

By analyzing the maps, we can ascertain that, in the case of shipyard officers, there was a concentration of privileges in places such as Vila do Conde, Porto, and Lisbon, since João II granted letters to Viana, Fão, Vila do Conde, Porto, Lisbon, and Setúbal. João III focused mainly on Azurara and Aveiro, and Manuel I and Sebastião and Cardinal-King Henrique turned their attention to Porto and Lisbon, respectively.

As far as navigation officers were concerned, Lagos, Portimão, Tavira, and Faro (in the Algarve), and Setúbal and Sesimbra (in the region immediately to the south of Lisbon) received the largest number of privileges. Nevertheless, we cannot ignore the clear presence of letters of privilege granted in Vila do Conde, Porto, and Viana do Castelo-i.e., municipalities located in the North. Although the bibliography (Polónia 2007a; Barros 2016; Moreira 1995) confirms the existence of significant seafaring communities in northern Portugal, the collected data indicates that the percentage of letters of privilege granted to navigation officers in this region was many times smaller when compared to the South (Oliveira 2017: 125). However, the fact that many of the letters were actually confirmations of previous privileges may, to some extent, account for the discrepancy that was pointed out.

Nonetheless, there was a distinct pattern to be noted in the distribution of privileges granted to shipyard officers: on the one hand, there was a substantial dependency on other shipyards besides the one located in Lisbon; and, on the other hand, while the shipyard officers of the South were granted more letters of privilege, most of the recorded documents served merely as confirmation of the privileges that had previously been granted to them, and did not therefore confer any new or additional ones. These facts would seem to justify the scarcity of letters of privilege addressed to navigation officers in the North.

Private Interests versus royal interests: pressures and deviant patterns

Based on the measures presented so far, while we can state that there was a clear and abundant legislative production by the Portuguese Crown aimed at normalizing and controlling this socio-professional body, these same measures also seem to reflect the reactions and pressures exerted on the Crown by seafarers. The process was not univocal and certainly not unidirectional (Polónia 2007a, vol. I: 413-493).

Carpenters and caulkers working at other shipyards in the realm were all too willing and able to put pressure on the Crown in order to attain social recognition- on a par with that afforded to their counterparts working in Lisbon-through the granting of privileges. Hence, in 1491,19 the carpenters from Vila do Conde, Viana, and Fão were granted privileges that were later extended to the Azurara and Póvoa do Varzim communities in 1502.20 In 1501,21 the privileges already enjoyed by the caulkers of Lisbon were granted to their fellow caulkers from Vila do Conde-an action that was also an extension of the privileges previously granted in 1497 to their counterparts working in Porto.22

The economic dirigisme established by Manuel I-fixing the freight rates and choosing the most convenient freights-never hindered the chartering of foreign vessels. At the same time, there was an active smuggling of vessels-mainly to Castile-in direct violation of the royal directives that forbade the sale of ships to foreign countries. This illegal activity was immensely hurtful to the Portuguese Crown because it limited the much-needed resources to compose its fleets and, at the same time, because the financial incentives that were generated by the privileges granted to shipbuilding, in terms of raw materials and tax exemptions as a means of promoting shipbuilding efforts, were automatically lost (Polónia 2007a, vol. I: 339-342; Polónia 2015: 220; Costa 1997: 35-6). This deviation from the norm, an enduring practice during those times, culminated in the promulgation of the Provision of the 19th of February 1569. On the Tonnage of Naus and Ships, which prohibited the sale of vessels to foreign individuals, by decreeing as follows: “if any individuals are interested in parting with their ships, they must sell them to those born and residing within our Kingdoms and Fiefdoms and never to outsiders” (Ferreira 1967: 343, my translation). In 1546, 1548, and 1550, there are reports of the Crown acknowledging the abundance of this practice. It was a profitable business that allowed foreigners access to a market from which, until then, they had been barred (Polónia 2007a, vol. I: 341; Polónia 2012: 356-357). According to Romero Magalhães (1970: 191), the profits to be obtained through the sale of ships to Castile justified the persistence of such a practice, even if it was illegal: a ship could be sold for three times the price paid by buyers within the Portuguese kingdom itself.

In addition to smuggling, these men knew how to take advantage of the more rewarding opportunities presented by serving in the fleets bound for the Spanish Indies, favoring them over the Portuguese Royal Fleets. As Amélia Polónia has proved, by analyzing the examinations of Portuguese seafarers in Lisbon and their distribution by navigation routes, we can see that the personal interests of these men prevailed over those of the Portuguese Crown. And, for the sake of their own safety and survival, they preferred more profitable navigation routes with better sailing conditions. Examinations undertaken at the Casa de la Contratación23 in Seville have proven the significant involvement of Portuguese professionals on the Spanish Indies route, certainly attracted by the guaranteed profits and by the lower risks that it offered, together with the opportunities presented by the slave trade routes (Polónia 2012: 355; Polónia 2015: 221). Conversely, during the times of the successive raids perpetrated by the Dutch and the English, the Portuguese Indian routes-and even the Brazilian ones-suffered drastic declines in terms of manpower at a time when the Crown was badly lacking the men needed to maintain its defensive fleets and trade routes (Polónia 2007a:, vol. I: 375-385; Polónia 2000: 39-40).

This desertion from the national fleets, also reflected in the lack of voluntary recruitment to those same fleets, justified the Crown’s resorting to apenamentos, or coercive recruitment. The payment of guarantees by ships’ masters to individuals to join the royal fleets in their place was yet another indirect way of avoiding recruitment to the Crown’s armadas. In the case of Vila do Conde, we have records showing that in 1608, a sum of fifty thousand reais was paid by four ships’ masters to two seafarers so that they could take the masters’ places in the armadas bound for India (Polónia 2007a, vol. I: 419; Polónia 2015: 212-213).

The direct involvement of sailors, masters, and pilots in the acquisition and management of vessels, acting as both their masters and their renters, enabled them to find alternatives to the labor market directed by the Portuguese Crown and consequently to distance themselves, to some extent, from the demands and needs of the monarchs. As businessmen themselves-albeit on a small or medium scale-they were presented with the opportunity to manage or participate in trading and/or shipping business networks by leasing vessels to third parties. The development of an investment strategy with a system of partnerships (purchasing shares in various ships) broadened the range of investment and created additional opportunities for small investors. In the same way as the reduction of the risks of loss due to shipwrecks or attacks from pirates may have justified the preference for purchasing shares in various vessels rather than risking one’s entire capital in a single ship. This very same risk control justified the evasion of the Crown’s recruitment endeavors and the avoidance of recruitment to the fleets responsible for defending dangerous maritime routes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, it seems evident that the system of control and incentives, diachronically developed by the Portuguese Crown and encompassing all seafarers, played a decisive role in guaranteeing the availability of the logistical means that were indispensable for the Portuguese overseas expansion. The dependency on these professionals and their knowledge for maintaining and defending the maritime routes was, however, a reality. Lobbying and negotiating mechanisms were implicitly identified in the royal legislation, which were employed both by the local powers and by the representatives of seafarers.

The Crown’s normative production shows how it intervened in accordance with the different conjunctures of that time, reflecting a reactive behavior that included a panoply of directives, ranging from incentives and privileges to the imposition of controls and punishments. Periods of crisis-especially those relating to defense issues, the lack of manpower for the composition of the naval fleets, and the ever-growing demands imposed by the naval administration-forced the Crown to adopt a more interventive role. The granting of privileges, the censuses, and the elaboration of general regulations are prime examples of this.

By taking control of all the registration, recruitment, training, and accreditation processes, together with the measures designed to dignify the seafaring profession, the Crown revealed an attitude in all contexts that was never passive. In fact, it adopted a proactive stance that was ultimately responsible for many of the successes achieved by the Portuguese expansionist enterprise. The awareness of its dependency on private initiative was, however, the starting point for the action that needed to be taken. This explains why there were policies that appear to have been discontinued and had no apparent strategic planning.

In certain circumstances, it is difficult to ascertain whether the complexity of the most significant legislative measures was a direct and immediate consequence of conjunctural pressures-as was the case in the reigns of João III, Filipe II, and Filipe III-or if they were due to a political attitude in which the action of the Crown was deliberately more regulatory and interventive regarding naval administration, including both seafarers and their routes. The reign of João III is a particular example of this, since the monarch is historically regarded as the sovereign who took the first steps towards building a modern state in Portugal and as the first Portuguese king to have conceived a colonial project (Cruz 1992; Thomaz 1994: 149-67).

The prologues to its own royal documents outline the Crown’s reactivity and proactivity and its incentive and/or punitive policies, referring to the pressure, the expectations, and the demands of seafarers, their local representatives, and their brotherhoods and corporations. To compel these usually tight-lipped agents-so often silenced by traditional historiography-to speak will require an additional effort on the part of researchers.