Introduction

On April 2, 1761, the Marquis of Pombal famously issued a decree informing the viceroy of India, as well as the governor-general of Mozambique, that local subjects of the Portuguese Crown in the Estado da Índia who had been baptized as Christians were to be granted the same legal and political rights as those born in the metropole (Boxer 1963: 73-74; Lopes 2006: 43). This celebrated decree aimed to establish “the juridical and social equality of Christian Asians in relation to the reinóis” as “His Majesty does not distinguish his subjects by their color but by their merits” (Boschi 1998: 333).2 Despite the decree not being fully enforced in Goa until thirteen years later in 1774, its spirit and the promulgation of other legislation aimed at improving the status of local subjects meant the middle decades of the eighteenth century witnessed changes in the management of diversity in Portugal’s overseas empire. These measures, coupled with the easing of more violent forms of religious suppression, have led some to characterize this period as “the more tolerant eighteenth century” (Pearson 2008: 117; Lopes 2006: 53) and as one in which the state veered towards “a new pragmatism” (Pinto 1994: 85). Importantly, however, the “principle of equality,” whereby local Christians in Goa were to be treated the same as those of Portuguese lineage, and the measures designed to ensure their greater participation in the ecclesiastical, political, and administrative institutions of the Estado were not concessions extended to Hindu subjects (Lopes 2006: 40). Indeed, although there was some slackening in the intolerance and discrimination they experienced in the Estado, Hindus continued to be subject to harsh restrictions on their religious and socio-cultural lives.

This article will thus evaluate the claim of the eighteenth century as one of tolerance by illustrating how the management of diversity in the eighteenth-century Estado was, in reality, characterized by the continued repression of Hindu religious practices. But while highlighting this sustained intolerance, it will also examine how and why the Estado experienced an incremental shift towards a more pragmatic tolerance, spurred primarily by the economic and political exigencies faced by the Estado over the course of the eighteenth century. First, its economic weakness consolidated its dependence on Hindu gentio (gentile) mercantile actors, while the latter’s agency in litigating for greater religious freedoms also forced a reconsideration of suppressive measures on the part of the imperial polity. Second, the brief but important period of expansion experienced by the Estado between 1747 and 1763, and its incorporating of the territories of the Novas Conquistas (New Conquests) and their predominantly Hindu population, also forced it to adopt a more pragmatic and tolerant approach.3 Indeed, the importance of the Novas Conquistas for the survival and viability of the Estado cannot be understated: they increased its territorial scope “four-fold” and transformed it “into a more coherent and manageable territorial entity” (Disney 2009: 321). The economic value of these newly acquired Hindu subjects, like those residing in the Velhas Conquistas (Old Conquests), made the case for greater religious tolerance more compelling.

But although the adoption of pragmatic tolerance was a necessary response to the challenges facing the Estado, this shift was still a fraught and tense process, and one that led to strong divisions among the various factions in the imperial polity. An evaluation of the limits of the Estado’s tolerance towards its Hindu subjects and its hesitance about granting them religious freedoms will thus demonstrate why we should approach this claim of tolerance with a more critical lens. This re-evaluation, however, is made difficult by the paucity of historiography on the Estado in the eighteenth century, particularly on the consequences of Portuguese imperialism for the local Hindu population. Moreover, the limited literature that does exist has largely approached the management of diversity from the perspective of the imperial polity, especially the “enlightened” principles and reforming zeal of the Marquis of Pombal from the mid-eighteenth century onwards.4 While the role of the imperial polity is key, this article will balance this top-down perspective by demonstrating how changes in the management of diversity were shaped from the bottom up, specifically through the agency, resistance, and engagement of Hindu actors.5 In giving more equal weight to these two perspectives, this article will provide a more comprehensive and complex picture of how the Estado grappled with managing diversity in the eighteenth century.

To evaluate how the Estado proceeded during the period in question, it is crucial not only to examine how it pivoted between a position of lesser or greater tolerance, but also how it accepted the usos e costumes (uses and customs) of the local Hindu population. This was most salient in the judicial and administrative sphere, and in the codification of Hindu legal norms pertaining to private, familial, and proprietary interests. This article will illustrate how the management of diversity during this period was also bifurcated between the suppression and restriction of Hindu religious identity, on the one hand, and the construction of a plural legal order that protected the local population’s pre-existing uses and customs, on the other. However, it will also examine how the protection of Hindu customs was a selective process and how the rights of Hindus to be governed by their own customs was determined “in the manner the agents of the Portuguese Crown found appropriate” (Xavier 2021: 44). Moreover, the ostensible acceptance of Hindu customs also led to their essentialization and fossilization, with their enforcement being continually subject to colonial interpretation and control. These tensions and the complexity of legal pluralism in the Estado, which denoted a selective tolerance towards Hindu uses and customs, were thus other aspects of how the Portuguese imperial polity managed diversity.6 There is, however, a considerable lacuna in our knowledge of the dynamics of this plural legal order during the period in question. To date, scholarship concerned with legal pluralism in the Estado has focused primarily on the foundations and construction of this order in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, or on the processes of codification and systematization seen in the nineteenth century.7 The production of legal codes and the creation of regulatory bodies that differentiated Hindu uses and customs in Goa, Daman, and Diu certainly meant the structure of legal pluralism was more clearly defined during this later period (Oliveira & Caleira 2020: 275-277). However, the manner in which the Estado enforced Hindu uses and customs and, in turn, administered legal diversity during a period that was crucial for its survival still requires further study.

As mentioned earlier, the selective tolerance of pre-colonial Hindu uses and customs not only essentialized and fossilized these norms, but also created and entrenched divisions between Hindu and Christian subjects. A closer examination of the complexity of legal pluralism in the Estado is thus central to understanding how diversity was defined and governed. Indeed, the role of law in structuring the political objectives of empire, and in defining and administering socio-cultural and religious differences in colonial societies, has been the subject of a significant body of historical scholarship.8 The creation of new legal frameworks and regimes for expanding control over imperial subjects, a process that also included the preservation of pre-colonial institutions, practices, and sources of legal authority, was not just a way of defining political authority, but also a way of imposing cultural differences and (altered) distinctions (Benton 2004: 1-2). Put simply, defining and recognizing legal diversity was also a means of controlling it. The codification of Hindu uses and customs in the Estado established an imperial framework of governance that extended into the private and familial domain of its Hindu subjects. Furthermore, the “politics of legal pluralism” meant that “contests over cultural and religious boundaries and their representations in laws became struggles over the nature and structure of political authority” (Benton 2004: 2). How then did Hindu subjects contest the suppression of their religious freedoms, and how did they engage with the “politics of legal pluralism?” How, too, did Hindu subjects in the Estado articulate their claims and grievances, and what was the imperial polity’s response to their demands? Answering these questions will provide insight into how the Estado shaped the dynamics of legal pluralism and, by extension, the management of diversity. As in other European imperial contexts, the engagement of local actors meant that constructing a plural legal order was an interactive but also messy and unstable process (Benton and Ross 2013: 4; Hickford 2018: 2). As this article will illustrate, Hindu actors employed the juridical apparatus of the imperial polity and engaged with the “politics of legal pluralism” to resist colonial impositions on their religious and socio-cultural lives, and also to further their individual interests where these ran contrary to defined customs. The manner in which they “used the rules to move strategically through the legal order” and to challenge customs further denotes the tensions in and complexity of how legal pluralism operated in European imperial contexts (Benton 1999: 564).

In order to better understand the complex factors shaping the management of diversity in the Estado over the course of the eighteenth century, we first need to gain an idea of what this state of diversity actually was. This first section of this article will therefore begin by briefly outlining the myriad religious, ethnic, and socio-cultural differences among groups in the local population of the Estado during this period. In particular, it will examine real and imagined differences between Christian and “gentile” Hindu subjects. What was the extent of differentiation between Hindus and Christians, and how did these divisions emerge? These questions will help us better understand how the Estado created, limited and accommodated difference in its management of diversity.

Section two will then examine the foundations of Portuguese intolerance towards Hindus and the measures taken to suppress their religious diversity. What were the nature and consequences of the harsh and sometimes violent measures used to suppress “gentile” religious diversity, and what were their consequences for the local Hindu population? Focusing specifically on the destruction of temples and the prohibition on public expression of private religious ceremonies, such as weddings and other life-cycle rituals, this section will demonstrate the extent to which Hindu subjects experienced restrictions on their religious and socio-cultural lives. To evaluate the claim of greater tolerance, it will illustrate the degree to which these restrictions persisted into the eighteenth century. The latter part of this section will outline the piecemeal shift towards a more pragmatic tolerance. How and why did the imperial authorities in Goa and Lisbon grapple with the question of granting greater religious freedoms? What was the contested nature of these changes, and how did this sow division among different factions in the imperial polity? The section will also highlight Hindu subjects’ agency in hastening the transition towards greater tolerance by examining how they litigated for greater religious and socio-cultural freedoms.

The final section will address how diversity was accommodated through the construction of a plural legal order, and the manner in which the Portuguese juridical sphere administered Hindu legal norms and customs during the period. How did the Portuguese codify and enforce what they perceived as Hindu uses and customs, and what was the role of Hindu actors in this interactive process? By analyzing a petition that sought to challenge the application of fossilized uses and customs governing Hindu laws of inheritance, this article will demonstrate the tensions inherent in the plural legal order.

The Estado of Diversity in the Eighteenth Century

The management of diversity in the eighteenth-century Estado was influenced by the complex and heterogeneous nature of local society, as well as by the underlying Portuguese imperial attitudes towards non-Christian or “gentile” communities. The population of the Estado formed a religious, racial, ethnic, and socio-cultural mosaic reflecting the continued settlement of pre-colonial communities and the hybrid groups that emerged as a result of Portuguese imperial consolidation. Put very simply, this degree of heterogeneity was reflected in the differences between the populations of the Velhas Conquistas (Old Conquests), being the areas acquired by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, and the Novas Conquistas (New Conquests), being the territories absorbed in the eighteenth century. The demographic composition of the Velhas Conquistas was multiracial, pluri-religious, and cross-cultural, with European-born Portuguese, known as reinóis, co-existing alongside mestiços (mestizos) or descendentes (also referred to Luso-descendentes), a category used to denote those of “mixed” Portuguese ancestry as well as Hindu “gentiles” and Muslims (Hespanha 2019: 110-111; Russell-Wood 1998: 210; Lopes 2006: 85-86).9 Although the category of gentio was a generic term used to refer to all non-Christians, the fact that Muslims comprised less than one percent of the population meant that, in the context of the Estado, the term largely applied to Hindus.

Christians outnumbering of Hindus in the territories of the Velhas Conquistas can be attributed to the success of the “Christianization of Goa” coupled with various measures aimed at repressing gentilismo (gentilism), such as conversion and the co-opting of local Brahmans, the introduction of the Inquisition, the destruction of temples and idols, the forced seizure of Hindu orphans, the banning of religious ceremonies, and the expulsion of Hindu priests and other elites (Boxer 1963: 81; Axelrod & Fuerch 1996: 409; Disney 2009: 315; Hespanha 2019: 99; Xavier 2008: 381-384). Moreover, the project of religious homogenization was accompanied by a significant number of laws that were “explicitly discriminatory” of non-Christians and that sought to reduce their political power, social status, and economic standing, while “discrimination in favour of Catholics against Hindus was deeply entrenched” (Xavier 2021: 55-57; Disney 2009: 57). As a result, intolerance toward Hindus was deeply rooted. Importantly, however, as well as the incorporating of the Novas Conquistas having greatly expanded the geographical boundaries of the Estado, these territories’ Hindu majority populations increased the number of gentile inhabitants within its borders. And so, while the absorption of these territories gave the Estado greater territorial integrity, and thus political viability, it also forced it to adopt a greater degree of pragmatic tolerance towards the pre-existing gentile religious practices and norms of the local population. Indeed, the Portuguese imperial authorities explicitly guaranteed the immediate protection of the uses and customs of the Hindu inhabitants in the territories of the Novas Conquistas.10

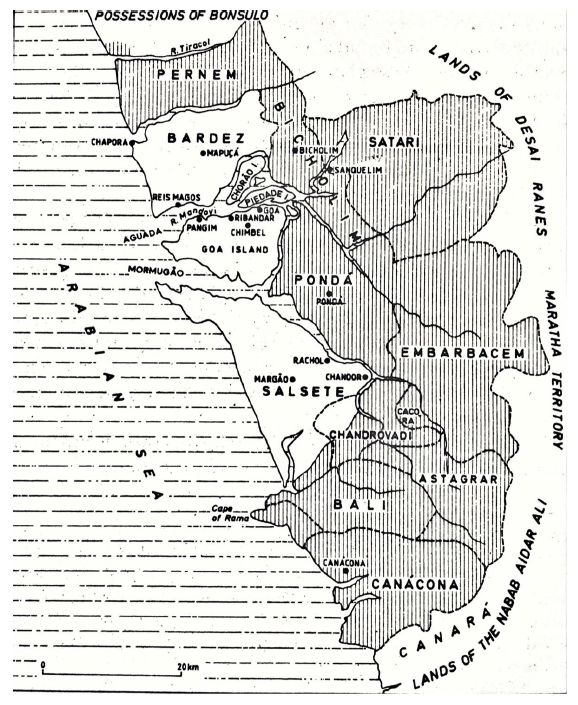

Figure 1: Map of Goa showing the territories of the Velhas Conquistas (in white) and the Novas Conquistas (shaded) (Lopes 2006).

In addition to the multi-ethnic, pluri-religious, and hybrid nature of local Goan society, its complexity was amplified by the existence of both Hindu and Christian caste communities. Although the caste system, as well as the sheer diversity of sub-castes present in the Estado, is too complex to address adequately here, the key point is to emphasize is that Hindu caste notions also existed among local Christian converts (Pearson 2008: 129). Within the Hindu population, upper-caste Brahmans belonged primarily to the Gaud Saraswat sub-caste, which formed the elite in the local society. According to a simplified hierarchy of caste among Hindus in the Estado, kshatriyas (sometimes referred to as a “warrior caste”) were ranked below Brahmans, followed by the merchant caste of vaysias or vanis (Banian), with sudras and farazes (who performed menial tasks such as sweepers or gravediggers) and chamares (leather tanners) considered the lowest castes (Russell-Wood 1998: 211; Boxer 1963: 75; Lopes 2006: 120). Despite initial efforts to eradicate the caste system as a way of eliminating all traces of “heathen” religious practices, caste distinctions persisted and converged with Iberian notions of the “purity of blood” and “nobility” as a key strategy and marker of social differentiation (Boxer 1963: 75; Lopes 2006: 111; Xavier: 2016: 113; Xavier 2010: 86; Bethencourt 2013: 179-180). Indeed, the durability and persistence of caste as a primary determinant of social status reflected the ongoing efforts on the part of local elites to distinguish themselves, as well as to gain access to positions of political and social power, by consolidating pre-existing markers of superiority. The significance of caste was also recognized by the Portuguese, with Brahmans considered a priority for conversion by Portuguese missionaries, particularly the Jesuits, who hoped that they would serve as an example for the unconverted (Bethencourt 2013: 180; Županov 1999: 27-28).

Furthermore, many local converts to Christianity still had a strong sense of “caste-consciousness,” with Brahmans in particular seeking to retain their upper-caste, elite distinction. Converted Brahmans thus engaged in a myriad of strategies to “forge” and “reclaim” a distinctive Brahman identity despite having “refashioned” themselves as Christians (Xavier & Županov 2015: 15-41). To achieve this, they continued to adhere to upper-caste Brahmanical societal norms and conventions, and caste continued to determine marriage patterns, entry into and membership of Christian confraternities, and where one sat in church (Pearson 2008: 129). Caste-based notions of superiority (and inferiority) also permeated into Christian caste groups: upper-caste Brahmans remained the elite, while chardos, who claimed a kshratriya caste status and were also known as ketris or a “fourth caste,” ranked below Brahmans but above canarims and sudras, who were regarded as the “lowest” castes (Dalgado 1919: 264; Boxer 1963: 75; Lopes 1996: 114).

Despite discriminatory practices and legislation favoring Christians over non-Christians, it should be emphasized that Indian Christians also experienced prejudice and unfair treatment (Disney 2009: 319). Within local society, the converted were considered lower than the honorable castes by virtue of their contact and mixing with outsiders (Bethencourt, 2013: 179). Indeed, it was precisely the unequal treatment of Indian Christians, exacerbated by the privileges granted to European-born Christians, that influenced Pombal’s decree cited at the beginning of this article. There was, therefore, no simple division between Christians and non-Christians in the Estado: instead, prejudice was directed and felt across and among these groups, and transcended the boundaries of religion, caste, ethnicity, and color. In this way, the redefining of social boundaries that Christianization enforced did not necessarily obliterate pre-existing social rivalries within local Goan society (Xavier 2008: 383). Moreover, new tensions and prejudices, such as those felt towards mestiços by reinóis and Christian Brahmans, also defined the complexity of social relations in the Estado (Boxer 1963: 76-77). From the perspective, however, of the imperial polity, there was an essential distinction between “gentiles” and Christians. Prejudice towards the former stemmed from a traditional Catholic conservatism that was still deeply suspicious of other religious faiths (Disney 2009: 317). Moreover, it also targeted groups who were considered competitors, such as Jews, Muslims, and, in the context of the Estado, Hindus (Bethencourt 2013: 33). As a result, the forced attribution of “gentile” status to the Hindus of the Estado meant they were still subject to widespread intolerance, which continued to fuel suppression of their religious freedoms.

Suppressing Diversity and the Shift towards Less Intolerance

Although attitudes towards non-Christians at the very beginning of Portuguese rule in India were “rather slack and tolerant,” from 1650 onwards “intolerance became the theme” (Pearson 2008: 116-117; Ames 2008: 2). The mission for the religious homogenization and “Christianization of Goa” (Xavier 2021: 55) hinged not only on the success of conversion, but also on measures undertaken to purge “gentilism.” In addition to the long-standing prejudices towards “gentiles” described above, these objectives thus formed the foundations of the attitudes of intolerance and suppression of non-Christian religious diversity, all of which had a profound impact on the religious and socio-cultural lives of Hindus in the Estado. The “Christianization of Goa” was carried out by religious missionaries and the orders responsible for spreading and managing the Catholic faith and for the conversion of locals. Moreover, the sometimes violent and coercive measures meted out by the Holy Office of the Inquisition monitored the piety of conversos (converts), especially Indian Christians, in order to prevent relapses into gentilismo.11 Between 1540-1640, a series of anti-Hindu laws were enacted to encourage religious uniformity (Ames 2008: 3-4), and ceremonies and “heathen” ritual observances concerned with birth, marriage, and death were also “drastically pruned” if not altogether forbidden (Boxer 1963: 81).12 Those suspected of “Hinduizing” behavior or of practicing syncretic or non-Catholic practices, or social practices associated with Jewish, Muslim, or Hindu religious influences, such as wearing a dhoti, possessing Hindu images, or refusing to eat pork, were subject to harsh punishment (Disney 2009: 319, Pearson 2008: 119-120; Lopes 2008: 132).

With regard to the suppression of Hindu religious diversity, the consequences of intolerance included the destruction of Hindu and Buddhist temples and the prohibition on public exercising of all “heathen” religious and ritual observances other than those belonging to the form of Roman Catholicism defined at the Council of Trent (Boxer 1963: 81). These measures had a profound impact, with the systematic destruction of Hindu (and Buddhist) temples and religious idols from the 1540s onwards said to have “had no parallel in any of the other territories” of the Portuguese empire (Pearson 2008: 116-117). The elimination of temples and idols, including those in private spaces, was accompanied by a ban on their reconstruction, and the lands on which destroyed temples had stood were given to Christian priests and Catholic religious orders (Pearson 2008: 116-117; Xavier 2008: 115-116). Other measures included expelling local priests and other high-ranking Brahmans, prohibiting the public celebration of Hindu ceremonies, and a decree issued in 1559 obliging all Brahmans to attend weekly Catholic indoctrination sessions (Xavier 2011: 211). In 1678, however, the complete ban on celebrating Hindu weddings was eased, with the result that such ceremonies were subsequently permitted, but only behind closed doors (Disney 2009: 315).

The harsh intolerance shown to Hindu religious diversity, coupled with the preferential treatment given to Christians, amounted to what many scholars have described as “systematic discrimination” (Axelrod & Fuerch 1996: 391; Pearson 2008: 148; Disney 2009: 317). The management of religious diversity during the mid-sixteenth century thus resulted in the near-complete suppression of Hindu public religious life, as well as the disappearance of Hindu religious symbols from the physical and socio-cultural landscape of the Estado. Other than in the territories of the Novas Conquistas, the ban on constructing and reconstructing temples was upheld during the eighteenth century, and public religious rites and ceremonies continued to be prohibited. As mentioned above, however, the importance of maintaining the presence of the Hindu majority populations in the Novas Conquistas-including the revenue that they generated for the Crown-necessitated adopting a less repressive approach to their religious practices during the period in question. The imperial authorities’ tolerance of these populations’ pre-existing customs and rituals was thus less the result of genuinely reformed attitudes, and more a strategy for winning over Hindus and securing their continued settlement in these areas (Lopes 1996: 53). Indeed, this pragmatism was reflected in a letter from 1756, dispatched from Lisbon to the viceroy in Goa, that spoke of the desire to “advance the culture of the lands conquered from the Sar Dessai Ramachandra Saunto Bonsulo.”13 This letter referred to an order of the king issued on November 24, 1754, which decreed “that the Gentios” in these lands “who wish to establish and rebuild their temples, be given the public use of their Religion.”14 Moreover, the viceroy was assured of the utility of granting these liberties, which would prove “useful until the end.”15

In addition to the need to ensure acceptable conditions for the Hindu majority population of the Novas Conquistas, the pragmatic approach of lesser intolerance in the eighteenth century was driven by the commercial weaknesses of the Estado that fueled its continued dependence on Hindu mercantile actors. The tensions between balancing the purging of gentilism and the Christianization of Goa, on the one hand, against the economic resources necessary for the survival of the Estado, on the other hand, were challenges that the imperial polity grappled with from the very beginning. The emphasis here, however, is on the continued dependence of the Estado on Hindu merchants, whose dominance over the colonial economy of the Estado was already evident in the seventeenth century (Pearson 1972; Souza 1975). As a result, and despite efforts to marginalize and suppress the Hindu population, the Estado could not do without the commercial acumen, resources, networks, and capital of its Hindu mercantile actors. Importantly, the “mutual dependency nexus” (Pinto 1994: 99-100) existing between the Estado and Hindu merchants extended beyond the commercial sphere, with their role as tax-farmers and diplomatic and commercial intermediaries compounding their indispensability to the imperial polity. In sum, therefore, the economic weaknesses of the Estado and its political vulnerabilities, coupled with the dominance of Hindu mercantile actors, tempered policies that sought to eradicate “gentilism” from the Estado, and forced a greater degree of tolerance towards Hindu uses and customs, and religious practices.16

Despite the intolerance lessening over the course of the eighteenth century in the Novas Conquistas, the suppression of Hindu religious life persisted in the territories of the Velhas Conquistas as well as in the province of Daman. This is evidenced by a response to a petition submitted by “the gentile people of Goa and Daman” which simultaneously addressed the ban on public weddings and the destruction of temples. The petition was sent to Lisbon, and a response containing details of the deliberations on its demands was returned to the Governor-General in Goa, D. Fredericome Guilherme de Sousa e Holstein, on March 5, 1781. Lisbon’s response explicitly noted that “representation [was] made by Hindu merchants” who were petitioning for permission “to celebrate the functions of marriages and the lines of their sons” and who stressed “the great prejudice and inconvenience” that the prohibition on public religious ceremonies had caused them.17 The response also made reference to “another representation by the gentile people of Daman which requested the conservation of their temples that were ordered to be razed and demolished.”18 The petitions of the “gentile people of Goa” and “the gentile people of Daman” clearly indicate that the ban on public celebrations of religious ceremonies remained in place and that the reconstruction of temples was still prohibited. Importantly, however, both petitions demonstrate the agency of Hindu subjects in seeking recourse to the legal channels in the imperial polity to litigate against these prohibitions.

The imperial authorities’ response to the demands articulated in these petitions also reveals the extent to which the shift towards a pragmatic acceptance of greater tolerance was a fraught and divisive process. According to the response, the petitions were sent to the “Archbishop of Cochin and the Administrators and Governors of the Archbishop” and to the “Prelates and Ministers of the highest reputation and learning” for “consultation.”19 The religious authorities still, therefore, retained a “disproportionate” influence in Goa (Disney 2009: 317) and held sway over questions relating to the governance and administration of the Estado. Unsurprisingly, the deliberations of the Archbishop of Cochin and the office of the archbishopric were overwhelmingly hostile to the demands articulated by these “gentile people” and strongly advised against granting them greater religious freedoms; in other words, permission to celebrate weddings or to re-erect and preserve their temples. What is striking, however, is that despite the ecclesiastical sphere’s influence, the religious authorities did not have the final say. Admittedly, their response stressed the “danger that the supplicants pose” and cautioned that the Estado should prioritize “the safety as always of the Catholic Religion which in all cases should remain permanently inviolate.” Furthermore, the Archbishop and Governors of the Archbishop of Cochin and the “Prelates and Ministers” referred to above recommended that the requests of the “gentile people” should not be granted in order to “save by all means necessary scandal to the Christian People of this Conquest.” But despite this strongly worded opposition, their recommendations were ignored-at least to the extent that the final decision sent to Goa included a compromise, whereby the imperial polity granted the “gentile people of Goa” the right to perform their weddings and the upanayana ritual ceremony. This is discernible from the document outlining the outcome of the deliberations point by point: the recommendation calling for the ban on celebrating Hindu ceremonies to be maintained is crossed out and, in its place, a note in the margin instructs the governor to “give permission to the gentiles of Goa for the marriages and those of the line as this seems just.” However, the second request was denied, with its being noted that “in what concerns the request of the people of Daman regarding the conservation of their temples this must be absolutely prohibited.”20

The question of allowing Hindu subjects in Daman the right to access and preserve their temples was a point of frequent deliberation for the Estado over the course of the eighteenth century.21 The need to preserve and attract the commercial activity of Hindu mercantile communities-such as Gujarati Banians or Vāniyā merchants, who were significant actors in Indian Ocean trade-forced a reckoning with prevailing policies that stifled their religious freedoms.22 In 1752, for example, the viceroy, the Marquês de Távora, sent a letter to the Mesa do Santo Ofício (Holy Office of the Inquisition) in which he stressed that “the decadence in which the assets and revenue the Praça of Daman are found” would be alleviated if commerce was stimulated. Boosting trade would allow Daman to “subsist on its Own Revenues without having to dispense them from the Erario of this State.”23 In order for this to be achieved, the viceroy proposed that “he would invite to move to that port some great merchants,” all of whom “are (gentiles) of good will who have offered to move but with the condition that they would be allowed to build temples and be publicly allowed to perform their Rites in the same form as they are permitted in Diu.”24 Although the viceroy himself was supportive of their requests, the Santo Ofício, while conceding that Daman needed to become self-sufficient was, unsurprisingly, strongly opposed to the viceroy’s proposal to allow the settlement of “gentiles” as a means to generate revenue. The Ofício returned a pointed response, cautioning that “a spirit so Catholic as that of Your Excellency [has] undetermined the concession of a condition which has as a consequence the cult of Idolatry real.” The response thus advised the viceroy that he “should not admit the Condition presented by these gentiles” despite “the profits that would make the independent conservation from the aid of the Erario Real.”25

The viceroy’s support for conceding to these merchants’ demands, which would allow the presence of temples and “the use of gentilic rites,” contrasted sharply with the response of the Office of the Inquisition that unequivocally sought the “exaltation of our Holy Catholic Faith and the abatement of idolatry.”26 This exchange, similar to the deliberations on the demands articulated in the petitions of the “gentile people of Goa and Daman” discussed above, reveals the extent to which yielding to greater tolerance was indeed a fraught and divisive process, as well as revealing how management of diversity differed across the territories of the Estado, particularly between Diu and Daman. The viceroy’s proposal noted that in “Diu the Temples and the use of gentilic rights are different” and that they are “on the other side of the City’s precinct and enclosed.” He also assured the Ofício that “in Daman permission could not take place if not on the outskirts which is where the gentios can be residents, because the Praça does not have more than one enclosure and inside it there cannot fit any other quality of people more than that of its current residents.”27 The emphasis, therefore, was on restricting the public visibility of their temples and open performance of their “gentilic rites.” The viceroy thus suggested that Hindu merchants should be settled in a similar manner to the “gentiles” in Diu. In other words, Hindu inhabitants should be effectively segregated from the Christian population which was “abundant” (Hespanha 2019: 104) and permitted to settle only on the outskirts of the city.

Accommodating Diversity

This article has so far illustrated how management of diversity in the eighteenth-century Estado centered primarily on limiting visible expressions of Hindu religious diversity. However, it has also shown how and why the imperial authorities grappled with their Hindu subjects’ demands for greater public religious freedoms and ultimately adopted a more pragmatic approach to tolerance. As demonstrated above, the imperial polity was responsive and conceded, for example, to allow Hindu subjects to perform two important ceremonies in public. In this way, therefore, the management of diversity became more accommodating to Hindu religious differences, as well as to the voices of Hindu subjects litigating for change. However, the most salient way in which Hindu differences were accommodated was in the manner in which their customs and legal norms were codified and enforced within the plural legal order of the Estado. The imperial polity’s intolerance thus operated alongside a more tolerant accommodation of selective aspects of pre-colonial Hindu legal norms and practices. How was this plural legal order constructed, and what was its impact on the ways in which Hindu customary law governed familial and private interests?

As Ângela Barreto-Xavier recently illustrated, the sixteenth century saw a visible impetus to document Hindu uses and customs, with concrete efforts being undertaken to identify the political, administrative, and judicial bodies and norms operating on the local level (Xavier 2021: 39). The foundations of the plural legal order in the Estado were set out in the Foral de usos e costumes dos gauncares (Charter of the practices and customs of the gauncares; henceforth referred to as the Foral), compiled by the revenue superintendent Afonso Mexia in 1526 and which documented the economic and political structure of the village communities of Goa, as well as their uses and customs. Moreover, it was also one of the initial documents issued by the Portuguese Crown to indigenous land administrators, or gaunkars (or gauncares)-the descendants of the first cultivators and settlers of the land-that reaffirmed their functions and formally recognized “the political significance” of the local legend consolidating their hereditary claims on the land (Axelrod & Fuerch 1998: 442; Pinto 2018: 185; Xavier 2021: 33) While confirming these privileges, however, the Foral also drew them into the ambit of the Portuguese imperial regime (Axelrod & Fuerch 1998: 454; Pinto 2018: 188). In this vein, it not only defined the duties and responsibilities of the gaunkars to the gauncaria, but also their ritual standing and privileges and their duties to the imperial polity. Clause fifteen of the Foral states, for example, that when gaunkars were summoned, “they are obligated to come” or to form a council to elect one representative from each village who wishes to respond to the call (Rivara 1865: 124).

Although the Foral was primarily a “fiscal document” and an effort to retain the village economic and revenue structures of pre-colonial Goa, it also made “visible (and decipherable) the legal matters of everyday local life,” and enshrined the principle of legal autonomy for Hindu subjects by preserving their pre-existing laws and customs (Axelrod & Fuerch 1998: 454; Xavier 2011: 259). Indeed, the Foral is considered as a “striking example” of early toleration that gave “due respect for existing Hindu social institutions” (Boxer 1963: 81). This act of preservation was still a selective process because the “pact between the state and the influential gaunkars” privileged the claims, objectives, and interests of these two parties above all (Xavier 2021: 34). But while the extending of this principle of legal autonomy in the sixteenth century was central to constructing legal pluralism in the Estado, how were the uses and customs that were defined in the Foral as “law” superimposed across the Estado and beyond the boundaries of the comunidades? The Foral was certainly imposed on the diverse populations and territories of the villages and the towns of Goa, which were governed according to an essentialized interpretation of village life (Xavier 2021: 50). Questions remain, however, as to how the Foral dictated and shaped jurisprudence in the Estado in practice, and to what extent it actually operated more broadly as the cornerstone for legal pluralism, specifically during the period in question?

The extent to which the Foral was central to accommodating and managing diversity can be ascertained by the degree to which changes implemented in the modern period were regarded as mere guarantees of what had been codified in 1561. The legal landscape and institutions of the Estado underwent significant change in the nineteenth century, as reflected, for example, in the production of three codes in 1824, 1853, and 1880 that regulated the uses and customs of the Novas Conquistas and the non-Catholic inhabitants of Goa (Kamat 2000: 74; Oliveira 2020: 278). The more extensive and rigorous codification of the uses and customs of Christian and non-Christian citizens also required a more thorough definition of their separate legal norms.28 As Rochelle Pinto emphasized, this “process of codification in the nineteenth century involved the translation of certain texts like the Manusmriti which began to represent a composite Hindu law” (Pinto 2007: 77). The legal protection provided for Hindu customs such as polygamy, adoption, and the joint-family system were described in the decree of 1880-also known as the “Code of the uses and customs of the Hindu gentiles of Goa”-as the “special and private usages and customs” of the Hindus (Kamat 2000: 74). The recognition and protection of Hindu uses and customs were also guaranteed after the introduction of the Portuguese Civil Code, which was implemented in the colonies in 1867. This move, however, reflected the “existing tension between principles of unity and diversity” that existed across the plural legal orders of the overseas territories (Nogueira de Silva 2015: 186). In short, therefore, the nineteenth-century legislative and legal changes were merely a “safeguard against the changes the Portuguese had successfully introduced into the lives of Hindus in the Old Conquests” (Pinto 2007: 77) and did not, therefore, constitute a radical change in the way that the Estado managed legal diversity based on uses and customs and the Hindu legal norms fossilized in the Foral in the sixteenth century.

To return to the eighteenth century, however, the tensions and dynamics in the plural legal order were salient in the ways in which Hindu subjects engaged with the imperial juridical sphere to arbitrate in disputes on inheritance. To reiterate, the laws governing inheritance among the Hindu population were based primarily on the customs codified in the Foral. This “addressed ritual practices, inheritance laws and a range of other aspects,” making it one of the few early modern documents explicitly concerned with defining and codifying customs pertaining to personal and family law (Pinto 2018: 188). Clauses twenty-seven to thirty-three of the Foral, for example, were concerned with matters pertaining to defunctos (the deceased) and inheritance. However, these customs were essentialized because the gaunkars and Hindu scribes who collaborated in compiling the Foral did not provide all the information at hand regarding their norms and customs, specifically the laws governing inheritance (Xavier 2021: 43). This meant that the enforcement and interpretation of these legal norms and customs governing inheritance were often murky and could be subject to dispute.

The extent to which the Foral was central to dictating legal pluralism in the eighteenth century is evidenced by a petition submitted by a Hindu widow by the name of Savetry Camotin. In March 1786, she submitted a petition that challenged the interpretation of the laws governing inheritance as codified in the Foral in an attempt to retain control of her deceased husband’s business house. After the death of her husband, Gopalla Camotin, with whom she had no children, Savetry Camotin “took weak and pacific possession of all the goods and assets of the house of her husband and her father-in-law Fondu Camotin.”29 Some time later, however, her control of the business house was challenged by a group of male relatives claiming to be the legitimate heirs and managers of Gopalla Camotin’s estate. Their claim to his estate rested on their being his only viable heirs, a line of succession that they claimed through their relationship to Gopalla’s mother, Laximiny Camotin.30 Savetry Camotin’s response to this challenge hinged on two claims and strategies. First, she articulated her right to retain control over the estate in a way that directly challenged the inheritance customs defined in the Foral. These customs, which may have been appropriations of Hindu Mitakshara law, prevented widows from inheriting from their husbands, and daughters from inheriting from their fathers and grandfathers (Xavier 2021: 49).31 Savetry’s second claim challenged the legitimacy of Gopalla Camotin’s self-appointed male heirs’ inheriting of his estate by citing their “maladministration” of the family’s assets, thus directly threatening the future of the business house.32

Regarding the first strategy, Savetry Camotin directly addressed the group’s claim that she was not a legitimate inheritor of Gopalla’s estate in the preamble of her petition. This began by referring to the “current general laws of this kingdom” and the “approved customs of the gentiles,” which meant that a widow was left with nothing “only what is necessary for her nourishment.” The petition further clarified this custom by stating that “[if] any gentile passed away without leaving a surviving male son and his surviving wife takes on a criolo . . . in the case of the death of the widow, neither her relatives nor her daughters stand to inherit as was practiced in many, many rich houses of the principal merchant subjects of this State.”33 The preamble thus confirms that the key principles of Hindu inheritance law upheld in the Estado prohibited widows from inheriting because clause thirty of the Foral stipulated that “[n]o daughter will inherit the estate of her father, nor of her mother” (Rivara 1865: 129; Pinto: 1996). But while affirming the existence of these “laws” and “approved customs,” Savetry Camotin nevertheless requested clarification of the laws stipulating the inheritance rights of sons whose fathers had multiple heirs.34

The information contained in the preamble of this petition thus helps answer several questions posed here regarding the structure of legal pluralism during the period in question. First, it confirms that the codifying and fossilizing of Hindu uses and customs in the Foral in the sixteenth century continued virtually unchanged into the eighteenth century. Moreover, the fact that these uses and customs were defined and approved of as law by the imperial polity reflects the tensions inherent in the constructing of this legal plural order. In other words, these uses and customs were indeed selected and enforced “in the manner the agents of the Portuguese Crown found appropriate” (Xavier 2021: 44). Second, the fossilization of the “law of the Foral and the gentilic customs” that served as the basis for the Estado’s plural legal order was maintained but reinforced by “many other decrees and providences.”35 Third, given Savetry Camotin’s residence in the city of Goa, the Foral was indeed superimposed on all Hindu subjects beyond the comunidades system. This projection perpetuated an essentialized and “imagined nature” of local Goan society that centered on the “village” and “village communities” (Axelrod & Fuerch 1998: 469; Xavier 2008: 145) and that was continually projected on the Hindu population of the Velhas Conquistas at large.36 Moreover, the essentialized nature of sixteenth-century Portuguese perceptions of Hindu uses and customs, which regarded the comunidades as the “locus” of idolatrous, diabolical social and religious customs, continued to influence the governance of Hindu legal norms in the eighteenth century. Importantly, the essentialized visions of local Goan society perpetuated by the Portuguese imperial polity also projected an antiquarian and fixed idea of Hindu uses and customs. Savetry Camotin’s petition, for example, affirmed that “gentile subjects” of the Estado had the right to be governed according to their own “ancient and immemorial inheritance customs” and not by “the general laws of this kingdom.”37 In sum, therefore, the management of diversity in the legal sphere of the Estado in the eighteenth century continued to be characterized by an oversimplified view of Hindu uses and customs in constructing a separate and plural legal order, an essentialization that was bolstered by Portuguese essentialist visions of local Goan society.

Unfortunately, the outcome of the petition is not known, and it is not clear whether the Estado decided to override custom and allow Savetry Camotin to continue managing the business house, or if it chose to abide by custom and to deny her the right as a widow to inherit the assets of her deceased husband. Nevertheless, her petition, which was a clear attempt to further her individual interests by challenging custom, denoted the possibilities that Hindu subjects perceived in their engagement with the legal apparatus of the imperial polity. The plural legal order thus not only afforded Hindu subjects the right to be governed according to custom, but also granted them an alternative forum in which to contest these legal norms. Savetry Camotin herself employed a complex strategy that appealed to the imperial polity’s benevolence by highlighting the harsh effects of these inheritance customs on widows, while also arguing that “blind” observance of this custom had “destroyed the houses and assets of the gentios in grave harm to the public for the continuation of commerce which they uniquely exercise for the utility of the State.”38 This criticism of blind adherence to custom suggested that a more critical consideration of these legal norms should guide how and why they were enforced, especially if they threatened the public good. Moreover, this emphasis on commerce clearly reflects the extent to which Hindu subjects themselves were acutely aware of the centrality of commerce in the pragmatic agenda of the imperial polity during this period. In aligning her own interests with those of the Estado, Savetry’s petition, in turn, demonstrated an equally strategic and pragmatic approach to the management of legal pluralism.

Final Remarks

This article has illustrated how the management of diversity in the eighteenth-century Estado was guided by a complex and multifaceted set of strategies that necessarily adapted to the political and economic exigencies faced by the imperial polity during this period. As such, it has shown how greater tolerance was not the result of changed attitudes regarding the practices or beliefs of Hindu “gentile” subjects, but rather a further demonstration of how the Estado pragmatically accommodated their demands for greater religious freedoms. Moreover, in delineating the extent to which the process of adopting a degree of tolerance was a fraught, forced, and divisive process, it has provided a more nuanced analysis of how and why the Estado became more tolerant towards its non-Christian Hindu subjects. The tangible consequences of this pragmatic tolerance were neither sweeping nor uniform: Hindu subjects in the territories of the Velhas Conquistas, for example, continued to experience harsh restrictions on their religious and socio-cultural rites and practices while these freedoms were immediately granted to the populations of the Novas Conquistas. Nevertheless, Hindus in Goa had to seek recourse to litigation in order, ostensibly, to be granted the right to conduct weddings and the upanayana ceremony in public while the question of preserving and reconstructing their temples continued to be contested.

As this article has illustrated, the management of diversity in the Estado and the role of tolerance were made more complex by the ways in which the imperial polity clearly and necessarily constructed a plural legal order that preserved pre-existing Hindu uses and customs “approved of” as law. The fossilization and essentialization of Hindu uses and customs, as codified in the Foral in 1561, continued to serve as the foundations of legal pluralism in the eighteenth century. However, as the case of Savetry Camotin highlights, these fossilized uses and customs were not perceived as being entirely set in stone. Hindu subjects’ broader engagement with the juridical authorities of the Estado reflects struggles and tensions in how the plural legal order and the management of diversity operated in practice. Returning to Lauren Benton’s emphasis on how the representation of cultural and religious differences in imperial legal regimes, and, by extension, the very structure of imperial rule, was structured by contestations over the meaning and importance of these symbolic markers, the ways in which diversity was managed in the eighteenth century can also be seen to have been marked by struggles and difficulties. These were reflected in the ways in which the imperial polity struggled to become more tolerant, and in which Hindu subjects contested intolerance and challenged efforts by the Estado to accommodate difference by enforcing selective uses and customs. In short, the construction of legal pluralism and the management of diversity in the eighteenth century were marked by struggles and contestations over the definition, governance, and consequences of difference.

In demonstrating, first, how Hindus themselves petitioned for greater religious freedoms in the public sphere and, second, the imperial polity’s responses to these demands, this article has additionally illustrated how management of diversity was also influenced from the bottom up. Importantly, the role of local actors in shaping legal pluralism, both in theory and practice, indicates a greater degree of Hindu agency in managing diversity than previously noted. Nevertheless, there is a caveat to this bottom-up perspective, given that the majority of the Hindu petitioners mentioned here, perhaps with the exception of the widow Savetry Camotin, were in fact local elites from the dominant castes in positions of power. As a result, while Hindu petitioners’ engaging with the juridical apparatus of the Estado to litigate against suppression of their religious freedoms can be characterized as a form of resistance, it was still resistance on the part of elites occupying a dominant and powerful position in local society. Thus, while the bottom-up approach employed in this article has sought to center on the voices of Hindu subjects, it does not claim to represent a subaltern perspective.39 This caveat and the attention paid to Hindu actors’ engagement with the imperial polity, as illustrated above, may also add nuance to the contemporary discourse on the legacy of Portuguese imperialism in Goa. The suppressive measures pursued by the Estado, and its violent and harsh intolerance towards non-Christians, are central tropes in contemporary discussions regarding the consequences of Portuguese rule. The “history of brutal Christian religious colonialism” and the “terrible suffering” of “persecuted gentiles” (Afonso 2008: xiii-xvii) perpetrated by the imperial polity continue to influence the collective memory of a significant section of local Goan society. But although these discussions are not entirely without merit-and this article has not eschewed the violent and suppressive consequences that intolerance had on the Hindu population of the Estado-they have a tendency to overstate the hegemonic power of Portuguese imperialism and to oversimplify the history of the relations between Hindu subjects and the Estado. As such, this more nuanced and informed analysis of the limits of imperial polity’s intolerance and Hindus’ agency in shaping the management of diversity in the Estado presents a more complex and nuanced picture of the consequences of Portuguese imperialism on local Goan society during the period at hand.

References

Archival Sources

Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (AHU)

Cx. 122

Historical Archives of Goa (HAG)

Monçoes do Reino, MR 152-125A.

Xavier Centre for Historical Research (XCHR)

Mhami Family Collection, Portuguese Miscellaneous Documents.

Printed Primary Sources

Rivara, J.H. da Cunha (1865). Arquivo Português Oriental fascículo 5. Nova Goa: Imprensa Nacional.

Dalgado, Sebastiāo Rodolpho (1919). Glossário Luso-Asiático. Coimbra: Imprensa de Universidade.

Xavier, Nery Felippe (1840). Collecção de Bandos e Outras Diferentes Providencias que serven de Leis Regulmentares para o Governo Economico, e Judicial das Provincias Denominadas das Novas Conquistas Precedida da Noção da sua Conquista, e da divisão de cada huma dellas. Pangim: Imprensa Nacional.