Environmental consciousness in Latin America is on the rise. Colombia’s first Leftist president, Gustavo Petro, was elected on 19 June 2022 in part based on his promise of a moratorium on hydrocarbon and mining projects. The concern in Colombia at the devastation wrought by over-development is not an isolated case. Chile’s new President, Gabriel Boric, also committed himself to strong environmental action. One of his first acts as president was to sign the Escazú Accord, which provides strong guarantees of environmental rights.

While much of Europe wrestles with the continuing impacts of the pandemic and the renewed waves of refugees from the war in Ukraine, Latin America deals with another kind of influx - of investors eager to capitalize on high commodity prices, governments wishing to create new infrastructure projects, and other developers looking to cash in on opportunities. The consequences of this development have often been devastating - contaminated rivers, loss of lands, oil spills and polluted water sources, noise and air pollution, and the absence of rights to information, participation in decision-making, and recourse to justice. Affected communities often lack the finances, experience, connections, knowledge, information, and other resources to defend their rights.

Latin America’s growing environmental emergency is deeply connected to Europe, to other parts of the Atlantic Basin, and indeed to the wider world. In this paper I review some of these connections, and how they impact the efforts of Latin American countries to address one of its weakest policy areas, environmental rule of law, or EROL. EROL is defined as ‘adequate and implementable laws, access to justice and information, public participation equity and inclusion, accountability, transparency, liability for environmental damage, fair and just enforcement, and human rights’.2 Serious weaknesses in EROL combined with poor governance more generally, widespread violence, and climate-induced environmental change have propelled vast numbers of migrants to seek better lives in other countries, especially the United States.

The Escazú Accord entered into force in 2021, binding twelve Latin America and Caribbean countries to Principle 10 (P10) rights (information, participation, and justice). They are ‘central to the relationship between the environment and human rights and form the basis of environmental democracy and good governance’.3 P10 rights stem from Rio 1992 and are now included in most Latin American constitutions as human rights. The Aarhus Convention in Europe created similar obligations for member states and entered into force in 2001.

Aarhus served as a model for Escazú, but the latter goes further (despite not including all Latin American countries). It gives citizens the right to contribute to decisions over land and natural resource use, and access to justice when disputes arise. It also creates a citizen participation mechanism, a ‘no repetition’ clause, a definition of vulnerable groups and citizens, and protections for environmental defenders. In some countries it will encourage new legislation to strengthen the P10 and environmental impact assessments (EIA) legal frameworks, provide better accountability for environmental crimes, and foster stronger prosecutors and courts with specialized tribunals.

Escazú addresses the chronic weaknesses in many Latin American countries in rule of law, human rights, and environmental justice. It comes at a time when international attention to EROL is rising rapidly. EROL is comprised of both human rights issues and more general regulatory compliance issues, such as licensing and permitting. Environmental human rights include a healthy environment, clean water, and access to certain resources or lands, as well as P10 rights. Indigenous populations have special guarantees to free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) rights, which are spelled out in ILO convention 169.4 Nevertheless, many signatory states in Latin America fail to implement these rights effectively even after ratifying relevant conventions, codifying them in domestic law, and even though they have large populations who are often in marginalized and precarious economic positions.

Various international organizations have recently reported on the state of EROL in Latin America and beyond.5 There is also some recent scholarship on EROL and indigenous rights6 as well as a growing body of work on legal processes in environmental governance, such as the EIA.7

The intense development pressures in Latin America are sobering, and conflict has surged as large-scale developments projects proliferate.8 In 2018, ECLAC warned of ‘the degradation of the environment and ecosystems and the plundering of natural resources associated with today’s production and consumption dynamics’.9 In its first global assessment of EROL (in 2019), the UN Environment Programme stated that despite the widespread growth in environmental laws and institutions, effective enforcement remains weak. It pointed to a lack of clear standards and mandates, insufficient funding and political will, not enough attention to the safety of environmental defenders, and few resources for civil society.10 The stakes are high not just for natural resources and the environment, but for those who defend them: the year 2020 was the worst on record for murders of environmental defenders, with 227 deaths worldwide.11

Many indigenous and rural farming communities in Latin America live near large-scale ‘mega-projects’ and suffer from the externalities associated with them.12 Development pressures are many: mining, hydrocarbon and renewable energy, transportation and communication infrastructure, and tourism, for example. Mining produces more conflict than other sectors,13 although it is less relevant in some countries, such as Brazil, Argentina, and Costa Rica, where agriculture, energy, and tourism produce more conflict.14 More than half of the precautionary measures granted by the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights related to the environment between 1997 and 2017 were for mining projects.15 Major cases include the Santurbán conflict in Colombia over mining in a protected wetland area; the Cajamarca case, also in Colombia, involving a gold mine. Energy projects also feature highly on the conflict scale, including the Hidroaysén hydropower project in the Chilean Patagonia; and the Belo Monte dam project in Brazil. All involved serious and prolonged socio-environmental conflict with neighboring communities.

The state is nominally the arbiter between development and eco-cultural or conservationist interests, and it must ensure that the rule of law prevails, because both sets of interests have socio-economic validity and political support. Yet it is widely accepted that Latin American governments have failed in this task. Political leaders often fail to provide full and timely information to affected parties, and to draw them in to the consultation process. They neglect to evaluate environmental risk and damage, draw in affected communities, consider alternatives and mitigation measures, and keep the spotlight on afterwards to monitor adherence. Regulators and prosecutors are often woefully underfunded and understaffed. Legal authority is sometimes insufficient to enforce laws. Courts and other institutions lack expertise on environmental matters.

Observers blame corruption or the lack of political will, but this masks a deeper structural power imbalance in which development interests benefit from the influence of economics, finance, and development ministries to the detriment of environmental ministries. In order to be effective, the state needs environmental institutions that are both developed internally - that is, with appropriate qualities of capacity and autonomy - and also engaged with civil society. Without these attributes, EROL suffers, exacerbating inequalities and injustices.16 Given this state of affairs, it is unsurprising that there has been an explosion of interest in EROL. Yet, while analysts have tended to focus on international pressures and on domestic institutional reforms when dissecting EROL, attention to the role of civil society actors is relatively scarce.

There is no reliable measure that allows accurate comparisons of EROL across countries.17 A recent study by the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) connects environmental conflict to institutional capacity, as measured by the WJP rule of law index, GDP per capita, ranking on the Human Development Index, the Economist Intelligence Unit’s democracy index, and the World Resource Institute’s environmental democracy index.18 The figures show that - among Latin American countries - Chile had both strong institutional capacity and low conflict escalation and consequences, while Colombia, Peru, and Mexico were closely clustered in the middle of the rank, with Honduras as the worst performer on both institutional capacity and conflict. An updated version of the study, published by the IADB and the WJP, provided indicators of environmental governance for ten Latin American and Caribbean countries.19 The indicators are both substantive (environmental outcomes) and procedural (the process of achieving outcomes). The results, derived from expert surveys, varied across indicator but generally showed that Costa Rica and Uruguay did well on environmental governance while El Salvador and Bolivia did poorly.

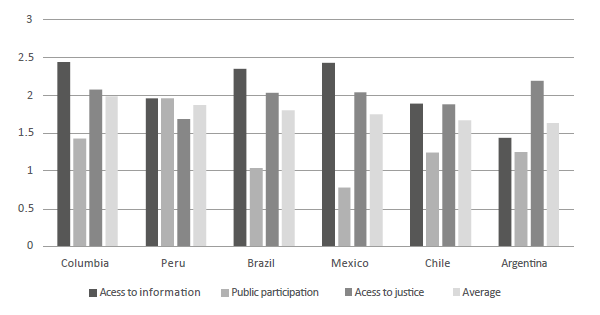

Another study gives a different impression. The Access Initiative and the World Resources Institute created an ‘Environmental Democracy Index’ with results for 70 or so countries on P10 performance, showing Panama and Colombia as highest ranked in Latin America and Belize and Paraguay as the lowest.20 However, there are wide discrepancies between their three indicators, with public participation the weakest in virtually all states (see figure 1). Interestingly, those countries scoring higher on the environmental governance index (Uruguay and Costa Rica) scored lower on this index. Perhaps because the indicators were different (governance is not the same as rule of law or procedural rights), or because the years of study differed, we have very divergent results in terms of country ranking, and therefore little certainty as to how well the countries are doing, never mind what causes variation in the indicators. Hence, it is hard to get a clear sense of the scale of the EROL problem, or a consistent measure of the relative successes and failures of each country.

International pressure to improve EROL

External pressure to improve EROL has brought some change, with Escazú being the latest example. Latin American countries are subject to the rulings and opinions of the Inter-American system and are closely monitored by other international organizations and actors, including NGOs, think tanks, and Western countries. For example, the Inter-American Court issued an opinion that EIAs are required in territories of indigenous populations, and also should be undertaken in cases where the development activity will likely have a ‘significant adverse impact on the environment’.22 In the Reyes vs. Chile case, the Court ruled that international law on human rights protects access to information.23 In 2007, it ruled in Saramaka People v Suriname that safeguards apply to protect indigenous peoples in cases involving large development projects, and that they have rights to participate in planning, enjoy a reasonable benefit, and benefit from independent social and environmental impact assessments. The Court also stated that information and communication are essential, as are good faith consultations, fairness in terms of timing (i.e., early in the process), and culturally appropriate consultations (such as with recognized tribal leaderships) which aim at agreement.24

The OECD has also issued judgements on environmental governance in countries that aspire to membership. In 2005, the OECD and ECLAC reported on Chilean environmental institutions and standards, including P10 rights, and made recommendations in advance of Chilean membership.25 The UN created a special rapporteur for the environment and human rights,26 and it also agreed a nonbinding declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples in 2007. The ombudsman’s office of the World Bank’s International Finance Committee has reported on investments that it supported in the region. Trade agreements with the United States have resulted in requirements to improve institutional or legal frameworks to ensure proper environmental governance. Furthermore, both the European Union and France have enacted so-called ‘due diligence’ regulations, which require firms to take into account human rights and environmental risks in their global supply chains, and provide remedies where there are damages.27

Domestic institutional pressures to improve EROL

These and other outside pressures have resulted in changes to domestic agendas, to the stated positions of governments, to institutions and policies and the procedures they follow. However, pressures to improve environmental protections and socio-environmental justice have also emanated from within Latin American countries themselves. Institutional and legal reform was fostered by democratization pressures from the 1980s onward. Yet environmental institutions continue to be weak in a Weberian sense, lacking authority, capacity, and resources.28 They are also weak in a functional sense - courts, tribunals, prosecutors, auditors, transparency agencies, environmental ministries and others are often outmatched by strong state economics ministries.29

Nevertheless, there are some institutional bright spots. Peru and Brazil created ombudsmen with strong reputations for opening access to justice.30 Colombia has financed legal defense for poor groups, and some countries have mandated that indigenous languages be included in official documentation.31 A number of countries have established environmental conflict observatories, and also a network of Latin American environmental prosecutors’ offices with both ombudsmen and attorneys general. Peru created an independent environmental prosecutor’s office in 2008 with about 150 specialized environmental prosecutors across the country.32 It reduced the involvement of the economics and mining ministries in environmental oversight, although it suffers from insufficient specialists,33 and has failed to rein in illegal activities (such as artisanal gold mining) in remote regions.34

In Brazil, the Ministério Público is a formidable prosecutor and ombudsman, with civil and criminal jurisdiction, the power to investigate and prosecute cases, and negotiate settlements with environmental offenders.35 It undertakes strategic litigation and case-specific prosecutions. Another institutional success is the environmental tribunals created in Chile in 2012, with powers to resolve administrative disputes. Their expertise has improved enforcement and the quality of justice.36 Other countries do not have specialized environmental courts, although generalist constitutional courts in Colombia and Costa Rica have done much to defend environmental human rights.

Costa Rica’s courts have very broad standing and low costs for those alleging environmental harm.37 The Colombian constitutional court is widely seen as progressive and engaged, issuing transformative rulings. It decides on the constitutionality of legislation, and on specific cases of alleged harm.38 In a 1997 case, it ruled that the U’Wa indigenous people have the right of direct participation in decisions affecting their territory, and that the state must protect their cultural and collective diversity.39 The case concerned an oil drilling dispute centered around indigenous lands. A decade later, the court ruled on prior consultation of indigenous people, distinguishing between impacts on indigenous society and impacts on society as a whole.40 Nevertheless, despite legal and institutional reforms, enforcement and compliance failures often plague environmental governance. Governments have conflicting priorities, economic interests overwhelm weak institutions, and criminal organizations threaten environmental defenders who interfere with their activities.

The role of expert NGOs

Strengthening state environmental institutions will not by itself overcome EROL failures, at least in the short term. Whatever the level of institutional capacity, there is an inherent conflict of interest between development and environmental objectives. Weberian attributes do not tell us much about the institutional logic of action - states want development, and that means environmental disruption. Moreover, even with the best will in the world, resources are limited, and corruption and crime are an ongoing problem. Fortunately, in many instances, the EROL gap is filled by professional, or expert, environmental NGOs.41 They are ‘expert’ in the sense that they are comprised of personnel with relevant training and experience in legal, scientific, communication, organization, and other relevant skills. Their purpose is to provide the resources necessary for communities to defend their rights, acquire legal advice and accompaniment, public relations and communication, and scientific research. They help transmit information on compliance problems, force governance issues into the open, and provide the pressure necessary to motivate state agencies42. However, despite the central role they play, there is surprisingly little research available on civil society and rule of law, and what does exist tends to be focused on security and crime or international development at large.43

Expert NGOs use a variety of methods to contribute EROL. They organize local communities, conduct independent research, communicate, build networks, and mobilize legal challenges. They have created coalitions to lobby for policy change or new political priorities (including conservation and action to address climate change), and they have drawn in scientists and technocrats, who are able to offer viable policy alternatives to governments. Organizing, mobilizing, and networking permit alliances to capitalize on their diverse strengths - legal, communication, strategic, data analysis, science, education, contacts, lobbying, social media, diffusion, and others. Independent information-gathering permits NGOs to spot the mismatch between the requirements of environmental law and actual behavior by environmental agencies. Communication permits issues to be framed discursively. Through litigation, social actors have highlighted the discrepancy between legal requirements and official behavior, and thus challenged noncompliance, corruption, and impunity.44 These NGOs are not spontaneous street activists or researchers or conservation organizations, nor are they site-specific. Rather they are permanent and national or semi-national in scope. Some of their legal activities are designed to promote the public interest broadly construed, whether through strategic litigation or education or awareness-raising activities or others. Other legal action defends rights in individual cases and among particular communities.

Expert NGOs vary from country to country, and also within countries. As an example, (the Mexican NGO) CEMDA’s main activities are litigation in defense of communities, although it also accompanies communities and trains them in legal strategies. Another Mexican group, PODER, undertakes research to counter the power of investors in extractive industries. Along with other NGOs, it published a detailed Human Rights Impact Assessment intended as an alternative EIA to evaluate a mining operation in the state of Puebla.45 The Chilean group FIMA mainly engages in strategic litigation rather than litigating specific cases. It seeks to raise awareness and improve communication around human rights and environmental issues. It does extensive research and publishes its own journal. Other Chilean NGOs include Defensoria Ambiental, working on socio-environmental conflict and defense of communities, and Geute, which does conservation, consulting, and legal research in Chile’s south46. One of Peru’s most important NGOs is SPDA, which has a litigation clinic that provides advice without itself doing litigation work. In 2020 it created an environmental justice branch to provide technical assistance.

In Brazil, environmental movements in the 2000s created organizational and legal advice networks in rural areas to try to prevent developers from evading regulatory responsibilities.47 The Belo Monte dam case showed how strong state institutions can structure civil society action: legal mobilization was handled by state agencies (including the Ministério Público), rather than NGOs. NGOs such as the Dam-Affected People Movement (‘Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens’) confined their activities to media strategies, direct action, and advocacy.48

It is important to understand the implications of this variation in NGOs activities. What is their role is in raising capacity among local communities and state institutions, how do they link to allied groups, what mechanisms do they employ, and what difference do they make? Participation can ensure the inclusion of affected communities, but can it be effective without expert NGOs? Also, we need to know how their strategies may be tailored to the local opportunity structure.49 Some opportunity structures may encourage more activism or lobbying, others may encourage more legal representation or research, others more education and training.

One of the most important contributions that expert NGOs make to EROL occurs during the EIA. The EIA is a means of reconciling development objectives with the rights of affected persons.50 Numerous international organizations and scholars have compared EIAs. In 2015 the World Bank published information on the legal framework for environmental impact assessments in Latin America.51 It has descriptions of seventeen indicators, including the names of the environmental authorities responsible for carrying out the EIA, the types of EIA instruments, screening and scoping requirements, alternatives, citizen participation, monitoring, reporting, and others. ECLAC’s 2018 report compared EIAs across Latin America, finding that they all require impact assessments, publicity and information, and public participation which takes into account public views.52

However, there are some important differences: Chile and Mexico have time limits for participation. Chile, Colombia, and Peru have requirements that citizen input be designed and implemented in a manner appropriate to indigenous communities. Chile’s 2012 EIA regulations require participation strategies to be adapted to the social, economic, cultural, and geographic contexts of areas and people in question. Chile has made proactive moves to include public input on climate action. However, most countries do not make citizen input binding on state agencies or developers. Scholarly work has found variation according to project selection and scoping criteria, participation requirements, transparency requirements, ministerial responsibilities.53 Reports from both international organizations and scholarly research indicate numerous criteria for best practice in EIAs.54 Moreover, NGOs have lobbied repeatedly for the legal processes to be strengthened.55

Building capacity in civil society

One problem with these studies is the assumption that the responsibility for helping affected communities falls principally on the state. The UNEP report states,

'[c]ivic engagement at times requires building the capacity of the public to engage thoughtfully and meaningfully with government and project proponents. Educating the public about their rights to access information and participate is a necessary first step, and providing tailored assistance when a community is unable to engage should be considered part of government’s responsibility. This can build a more robust citizenry that can support stronger government and rule of law’.56

Despite this focus, little attention has been given to how to support these NGOs. Civic engagement is often presented in passive terms, namely that the state should provide information and opportunities for participation.57 Similarly, the EDI report argues that ‘States should provide means for capacity-building, including environmental education and awareness-raising, to promote public participation in decision-making related to the environment’.58 There is no indication of how this would be undertaken or measured, nor what resources, personnel, training, and incentives would be needed in order to implement public participation requirements correctly.

In its 2018 report, ECLAC’s position on participation was that Latin American states should clarify legal obligations and make more precise the scope of participation requirements. They should endeavor to begin consultations early, with adequate and easy to understand information, appropriate time limits, assistance for affected communities (financial and technical), and a generous interpretation of who may participate.59 However, in a scenario where information is held by the developer and participation is controlled by the state, simply opening the door will not have the desired benefits if civil society does not have the capacity to engage on the same terms as development interests. Engagement in these reports looks little different from consultations, or information sharing, and it is unclear how it would build civil society capacity, or what mechanisms and tools would be necessary. To achieve the objectives, state agencies would need to lead workshops, help interpret the implications of a project, provide wider context and a series of feasible alternatives to the project design, commit to ongoing dialog, reveal the precedents of other cases, indicate what the regulations say and allow, and be available for periodic consultation. In Latin America, virtually all of these capacity-building projects have come from expert NGOs, rather than the state.

Instead of trying to guarantee perfect EROL by itself, states should focus on supporting expert NGOs. The idea would be to build legal and policy know-how, better communication skills, and financial and information resources among environmental, human rights, indigenous, and community groups, who are clearly the weaker partners in development disputes. Also, the state should engage proactively with both developers and opponents, be open to innovative solutions to conflict, provide complete information on proposed projects, including non-technical summaries, in a timely fashion and in relevant indigenous languages as well as Spanish or Portuguese, and communicate best practice.60 This may be a lot to ask, given resource and capacity deficiencies, but arguably it is a more sustainable strategy since it means that state agencies would not have to engage and train local communities one after the other. Instead, states could help create capacity in important NGOs so that the NGOs in turn can deliver this training.61 Activist institutions would bring environmental governance down to the ground, working closely with social actors to conduct the activities required - evaluation, licensing, investigation, prosecution, adjudication, conflict resolution, and so forth.

More attention is necessary to understand these dynamics. Atlantic partners in Europe and North America can do much to help, including through funding and awareness raising, legal pressures, research, and publicity. The security of all Atlantic basin partners depends on this crucial issue.