INTRODUCTION

Regular participation in physical activity plays an important role in helping people have healthier, balanced, productive, and happy lives (Vlachopoulos & Karageorghis, 2005). Before the coronavirus pandemic, the global health club industry finished the decade with record performance (Deloitte, 2021; IHRSA, 2020). In fact, today, thanks to the increase in awareness of healthy living, the interest in fitness centres has also increased. However, though the number of members of fitness centres decreased in 2020 by –15.4 million to 54.8 million, fitness is still considered to be the number one sports activity in Europe. The total income of fitness centres increased to 18.9 billion Euros (Deloitte, 2021).

Despite this growth in fitness centres, the fitness industry continues to be characterised as an industry where members can easily leave (Alexandris et al., 2022; Clavel San Emeterio et al., 2019; Gonçalves & Diniz, 2015). According to research, when customers are dissatisfied with the service quality, only 4% report this to the business management, while disappointed customers terminate their fitness membership (Zarotis et al., 2017). A customer dissatisfied with service quality informs seven potential customers about bad service (Bly, 2003; Tsitskari et al., 2006). Fitness businesses spend large sums to find new customers to replace those lost. In fitness centres, meeting expectations and differentiating from others in the eyes of the member is related to service quality (Rieger, 2012). The increase in the number of fitness centres in the last decade has raised competition and changed customer expectations. This change has led fitness centre managers to better understand their customers and meet their expectations at the maximum level (Jasinskas et al., 2013; Kriegel, 2012).

Service quality is a widely discussed concept in businesses, especially fitness businesses. When the body of literature is examined, it can be seen that the relationship between service quality in fitness centres with attitudes such as satisfaction, commitment, and behavioural intent has often been revealed (Fernández-Martínez et al., 2020; García-Fernández et al., 2018). At the same time, many scales related to service quality in fitness centres have been developed (Chang & Chelladurai, 2003; Lam et al., 2005). However, all these developed scales were limited to certain dimensions of service quality. For example, Lam et al. (2005) evaluated the service quality in fitness centres on the SQAS scale (Service Quality Assessment Scale) in six dimensions: staff, program, locker room, physical facility, workout facility, and childcare.

Chang and Chelladurai (2003) defined the quality of service in three dimensions and nine sub-dimensions as input (Service Climate, Management Commitment to Service Quality, Programming), throughput (Interactions persona/task, physical environment other clients’ service failure/recovery) and output (Perceived service quality). When this and similar studies are evaluated, it can be seen that the scales of service quality in fitness centres have been systematically developed, and service quality has been gathered under certain dimensions. However, in these scales, the fact that even a single sub-dimension of service quality can contain many sub-dimensions may have been ignored.

Many researchers in the literature have identified the quality of the physical environment (Papadimitriou & Karteroliotis, 2000) and staff (Chang & Chelladurai, 2003) as a dimension of quality. However, in many scales, the fact that these dimensions may have sub-dimensions has not been taken into consideration. What is missing here is the multidimensionality of quality. For example, trainers can emerge as a dimension of quality in fitness centres when measured by the positivist paradigm. Yet, the important point is which trait of the trainers will grant them quality in the member’s eyes. For example, elements such as the appearance or communication of the trainer can be a factor in the evaluation of the trainer’s quality, and more factors may arise in relation to this quality. In this context, the quality of other dimensions determined in the theoretical structure of the service quality in the fitness centre may be related to many factors. It may not be possible to learn this through the positivist paradigm. Nonetheless, it may be possible to learn the subject in more depth, thanks to qualitative research.

Fitness centres have become reference sports facilities for the spread of sports in society and the elimination of physical activity (Baena-Arroyo et al., 2020). But the growing interest in fitness services demands optimal service management and operation (León-Quismondo et al., 2020). Therefore, one of the most important elements for the success of fitness centres is a detailed understanding of quality elements. It is noteworthy that there is a paucity of qualitative studies that will fill this gap and give more details about what quality includes.

As evidenced, the traditional approach to the current problem in the sports and fitness industry has been through quantitative research. However, the closed nature of quantitative questions can be enriched with qualitative data (Felipe et al., 2013). This research, on the other hand, will fill this gap and will help us to understand the quality of fitness centres in more detail (Brady & Cronin, 2001; Lam et al., 2005) by completing the elements of personnel, the physical environment and program quality in more detail than has been identified in the literature to date. Therefore, the aim of this research is to determine the general factors affecting the quality of fitness centres in terms of the opinions of their members and the relationship intensities of the features within these factors.

Methodological framework

Service quality

Service quality is defined as the difference between consumers’ expectations about service performance before service is provided and their perception of service after consumption (Lehtinen & Lehtinen, 1991). It is also expressed as the level of service provided to meet the expectations of consumers (Parasuraman et al., 1985). Grönroos (1984, p. 37) defined “Service quality as a general impression or attitude related to the excellence of service”. Providing quality service is one of the main strategies for success in a fiercely competitive environment. It is an important factor for businesses that want to increase their customer volume, maintain continuity, get ahead in the fight against competitors and provide the continuity of the income that they obtain from their customers (Yu et al., 2014). Researchers have paid intense attention to service quality because of its importance.

One of the first models in service quality was developed by Grönroos (1984). In this model, he proposed three dimensions -technical, functional and image- for the evaluation of the service quality. Technical quality is the evaluation of what the customers achieve as a result of their interaction with the business service. Functional quality is about how the customer receives the service, apart from technical quality. While functional quality is about the delivery of the service, technical quality is a review of what is offered. Image is the dimension appearing as a result of the technical and functional quality of the service (Grönroos, 1984).

Another approach to service quality is the disconfirmation paradigm proposed by Parasuraman et al. (1985). According to this paradigm, the quality perception of the service is determined by comparing the expectations of the customer and the actual performance of the service provided by the supplier. If the expectation is higher than the perceived service quality, the perception towards quality will not appear satisfactory. If the expectation is equal to or lower than the perceived service quality, a satisfactory perceived quality will be obtained (Parasuraman et al., 1985). Researchers have developed the SERVQUAL model for use in the assessment of service quality in many industries. According to this model, the service experience is measured by the dimensions of reliability, responsiveness, empathy, assurance, and tangibility (Parasuraman et al., 1985).

The SERVQUAL model has come in for criticism over time (Yıldız, 2012). Cronin and Taylor (1992) developed the SERVPERF scale by claiming that this model has shortcomings. They stated that this scale encompasses much more diversity and that it is not satisfaction-oriented like SERVQUAL but performance-oriented. In addition, the researchers criticised that the SERVQUAL model is accurate in only two of the four industries. In short, although both models have strengths and weaknesses, they are still being used, and there is no consensus on which model is more appropriate (Yıldız, 2012).

Service quality in fitness centres

When the literature on the service quality of sports and fitness centres is examined, it is seen that the researchers have revealed general and specific quality model structures. Scales such as An Instrument for Evaluating Service Quality of Health/Fitness Centers (SQAS) by Lam et al. (2005), The scale of service Quality for Participant Sport (SSQPS) by Chang et al. (2005), A Hierarchical Model of Service Quality for Recreational Sport Industry (SSQRS) by Ko and Pastore (2005), Scale of Quality in Fitness Services (SQFS) by Chang and Chelladurai (2003), Factor Quality Excellence of Sports Centers (QUESC-4) by Papadimitriou and Karteroliotis (2000), Center for Environmental and Recreation Management-Customer Service Quality (CERM-CSQ) by Howat et al. (1996), Quality Excellence of Sports Centers (QUESC) by Kim and Kim (1995), Evaluation of Perceived Quality in Sports Services (CECASDEP) by Morales Sánchez et al. (2009), and Service Quality in Fitness Centers Scale by Sevilmiş and Şirin (2019) have been developed. Similar and different dimensions were used in each measurement tool to evaluate the service quality in fitness centres. In particular, programs, instructors, staff and physical environment attract attention as the most important structures used in measuring service quality in fitness centres (Jasinskas et al., 2013; Yıldız, 2011). Today, due to its importance in fitness centres, many authors are researching and analysing the quality of service (De Farias et al., 2021; Eskiler & Altunışık, 2021; Peitzika et al., 2020; Polyakova & Ramchandani, 2020; Pradeep et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021; Yıldız et al., 2021).

The dimensions used in the service quality assessment of fitness centres are generally defined by the quantitative research paradigm. This paradigm is criticised for ignoring the effects and consequences of social and cultural infrastructures, which are becoming more and more prominent due to the developing and changing world conditions (Potter, 1996). The qualitative paradigm gives a chance to examine the overall quality of fitness centres with a more holistic perspective by paying attention to the social and cultural influences, the perspectives of the participants and the fact that the participants represent different classes (Gioia, 2021; León-Quismondo et al., 2020). Hence, this study aims to determine the elements related to the overall quality of fitness centres from the perspective of the participants using the qualitative research paradigm.

The factors associated with service quality in fitness centres

The service quality in fitness centres is formulated as the consumer’s judgment about the overall excellence or superiority of the enterprise. Fitness members pay more attention to some factors (such as the physical environment) when evaluating the quality of service in their centres (Polyakova & Ramchandani, 2020). In many studies of fitness centres, the physical facility, staff (instructor, other employees) and program have been identified as elements of quality (Chang & Chelladurai, 2003; Ko & Pastore, 2005; Lam et al., 2005).

The quality of instructors and staff

Staff who manage to shape and give attention in a customer-oriented manner have an important place in the customer’s commitment. Qualified employees play a key role in the success of fitness businesses. Employing qualified employees in line with the understanding of customer-oriented staff management will enable the training processes to be shaped appropriately. Personnel involvement and employee competence are the basis for the success of the customer’s training (Rieger, 2011). The presence of qualified employees in the fitness centre allows using the staff in a customer-oriented manner and shaping the training processes in a customer-oriented manner. Achieving training goals and solid performance in sports is not only related to having adequate or quality equipment but also to the personnel involvement and the employees’ competence (Brady & Cronin, 2001). Hence, the instructor is the key factor in achieving the member’s goals in fitness centres. Many scales developed in the context of fitness considered staff as a dimension of quality (Brady & Cronin, 2001; Lam et al., 2005).

Morales Sánchez et al. (2009) identified one dimension of the Evaluation of Perceived Quality in Sports Services (CECASDEP) scale as “trainers”. In other words, they found that the trainers are a sub-dimension related to fitness service quality. Some studies have found a significant positive relationship between staff and satisfaction (Zopiatis et al., 2017). However, all these studies have considered the staff or trainers as an element of quality. When the related body of the literature is examined, it can be seen that the question of which feature produces trainer and staff quality, in other words, what are the qualities that bring about instructor and staff quality, is not discussed much.

The quality of the physical environment

The quality of the physical environment of the fitness centre points out the existence of certain physical elements that will increase the individual’s preference for using it. This includes elements such as spatial design and usability, symbols and signs, and the atmosphere (Firmansyah & Mochklas, 2018). The physical environment is defined by customers as the way machinery, equipment and furniture are arranged, the distance between the equipment and the tangible visible elements that facilitate the achievement of these goods’ customer and employee goals. Most scales in the context of service quality developed for fitness centres have considered the physical environment quality as a dimension of quality in fitness centres (Chang & Chelladurai, 2003; Chang et al., 2005). At the same time, the physical environment quality has been associated with many variables. Zopiatis et al. (2017) found a positive, meaningful relationship between the physical environment quality and satisfaction in their research. Wu and Ai (2016) detected a positive relationship between the physical environment quality and experience quality. There are many studies indicating that the physical environment quality in fitness services is a component of quality (Ko & Pastore, 2005; Lam et al., 2005). Brady and Cronin (2001) determined that the physical environment quality consists of sub-dimensions such as ambient conditions and design. León-Quismondo et al. (2020), as a result of interviews with 23 fitness managers, determined the importance of the tangible quality elements required to provide good customer service. The most important factors related to the physical environment were the changing rooms and cleanliness. Though all this research remains valid, more information is needed on the dimensions associated with the quality of the physical environment in fitness centres.

The quality of the program

The services provided by fitness centres differ from the services of other organisations (Wei et al., 2010). One of the reasons for this difference is the program quality. Pulling in new customers and maintaining customer loyalty effectively and efficiently occurs thanks to an interesting program design (Firmansyah & Mochklas, 2018). Scales developed in the context of service quality in fitness centres identified program quality as a dimension of service quality (Kim & Kim, 1995; Lam et al., 2005). Papadimitriou and Karteroliotis (2000) reviewed the quality excellence of the sports centre (QUESC) scale presented by Kim and Kim (1995) and revealed an 11-dimensional structure. One of these dimensions is program availability. León-Quismondo et al. (2020) highlighted the importance of group programs in their research with fitness centre managers. They expressed the view that the abolition of these programs will clearly affect the long-term sustainability and economic balance of fitness centres. While the scales developed consider program quality as a component of quality, there is not much in the related body of literature about the features that determine it.

METHODS

Participants

The participants of the research consist of 26 individuals who are members of different fitness centres in Turkey. Twenty-six fitness members were interviewed and chosen using purposeful sampling. The participants participated voluntarily and gave their consent. In recent discussions, a consensus has been reached that the basic sample size for ideal qualitative research is related to the quality of the data obtained from the sample (Sevilmiş & Yıldız, 2022). An important misconception that is often encountered in the literature and that qualitative researchers fall into is that larger samples can give more details and better reflect the universe. However, in qualitative research, the quality of the sample, not the quantity, is important (Mertens, 2014). For this reason, in this study, people who have experienced fitness services for at least one year were interviewed for research purposes. At the same time, attention was paid to the saturation point in the themes formed. The interviews ended when the saturation point was reached (West, 2001). At the same time, many studies carried out in the sport context have worked on a sample that has a lower number of interviewees than our sample and can give more details (De Lyon & Cushion, 2013; Dixon & Warner, 2010; Fowler et al., 2019; Winand et al., 2022). The personal characteristics of the interviewees are presented in Table 1.

Procedure

In this study, the qualitative research paradigm was utilised to collect, analyse, and interpret the data. The research data were collected using a semi-structured interview technique. Semi-structured interviews are one of the most widely used data collection methods in qualitative research (Bradford & Cullen, 2013). The reason why this method is included in the study is wishing to understand the experiences of fitness members in an in-depth way (Flick, 2018). During the interviews, the participants were asked four questions that were structured to learn about their personal variables and five questions that were semi-structured to achieve the purpose of the research. The collected data were analysed using a thematic analysis method widely used in sports (Evans & Lewis, 2018). Interviews were conducted by the researchers face-to-face or via Zoom. Both audio recordings and notes were taken during the interviews. The researchers informed the interviewees about the purpose of the research before in order not to deviate from the research aim. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes. The four semi-structured questions asked within the scope of the research purpose are presented below.

Q1: During the process of receiving a fitness service, what features do you think are important for the quality of the fitness centre for the people you interact with (everyone you interact with: office workers, other members)? Why?

Q2: Who do you think is a qualified trainer in a fitness centre? What makes trainer quality?

Q3: When the physical elements of the fitness centre are evaluated, what physical component should a fitness centre have to provide them with quality?

Q4: When the programs of the fitness centre are evaluated, which features of the programs offered in a fitness centre make up program quality?

Service quality researchers have not found a consensus as to the most objective model of the assessment of service quality. Despite this, many researchers in fitness services have used certain dimensions (such as the physical environment, the program, and the personnel quality) in the evaluation of fitness service quality. That’s why these questions were asked (Jasinskas et al., 2013).

Data analysis

In this study, designed with a qualitative method, overlapping coding was performed on the interview texts in order to derive the relational analysis of the quality elements of the fitness centre according to the opinions of the members. Overlapping coding refers to the presence of more than one code in the same text and the overriding of them (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2019). It is quite possible for two coders to assign codes with the same name to the same passages in the document. This is called relationship coding. Associated coding occurs when the interviewee expresses more than one theme in her /his sentence. What makes a fitness centre have quality? The respondent can refer to more than one factor in a single sentence. For example: “a fitness centre is of good quality if it has qualified personnel and a sufficient physical environment.” can form a sentence. Here, since this sentence is related to more than one factor (personnel and the physical environment), related coding is done. While coding this research data, related coding was performed.

The data were analysed with the licensed MAXQDA program. The MAXQDA is a widely used program for sports research in general (Walseth, 2008) and management research in particular (Niazy & Nazari, 2020). MAXQDA, a qualitative data analysis program, is a program with many possibilities, such as fast coding, naming the encoded data and showing code relationships with options (Sevilmiş & Yıldız, 2021). This is why this program was preferred. A code relations scanner was used while visualising the data. The code associations browser serves to view the co-occurrence of two codes in a section or document.

Validity and reliability

Some precautions were taken regarding the validity and reliability of the study. Validity in qualitative research is whether the research fits with the reality in the outside world (Silverman, 2020). Attention was paid to the correct execution of the data collection process, and sufficient participation was achieved. Saturation point has been taken into account while continuing to observe the research. The saturation point is where the codes appear to repeat the same things (Sim et al., 2018). At the same time, for the validity of the research, the data were coded by considering the body of literature and the data collection process was carried out by the researcher. Hereby, the validity framework of the research was tried to be provided.

When “reliability” is discussed in qualitative research, it generally refers to the level of agreement between coders (Joffe & Yardley, 2004). Inter-coder agreement is a numerical way of negotiating between different coders regarding how the same data should be encoded (O’Connor & Joffe 2020). The reliability of this study was provided by the agreement between the coders, as well. The MAXQDA qualitative data analysis program was used to support the inter-coder agreement calculation. It is common to use qualitative data analysis programs in inter-coder agreements (Nili et al., 2020). Hereunder, four interviews were coded by two independent coders, and the coded interviews were examined with the program’s inter-coder reliability calculation option. If a poor result is obtained, it means that the code or theme has been discussed and re-coded. After an acceptable level of inter-coder reliability, the final results of the agreed “code occurrence in the document” and “code frequency in the document” were determined.

In the case of the code occurrence in the document, it was seen that 29 codes were agreed upon and 3 codes were not. The agreed and disagreed codes were calculated over the Matches/ (Matches+ Non-Matches) formula. Accordingly, the agreement between coders was calculated as 26/ (26+ 3)= 0.89. By multiplying this number by one hundred, the agreement between coders was determined as 89%. When the final results of “code occurrence in the document” were assessed, it was seen that the agreement percentages between coders were at a sufficient level (Sevilmiş & Yıldız, 2021).

RESULTS

The participants interviewed evaluated the perceived quality in fitness centres in terms of the fitness centre’s staff, physical environment and program quality. According to the answers given to the questions asked, the participants considered the quality elements in fitness centres as follows. The thickness of the lines between the concepts in the figures shows the density of the relationship.

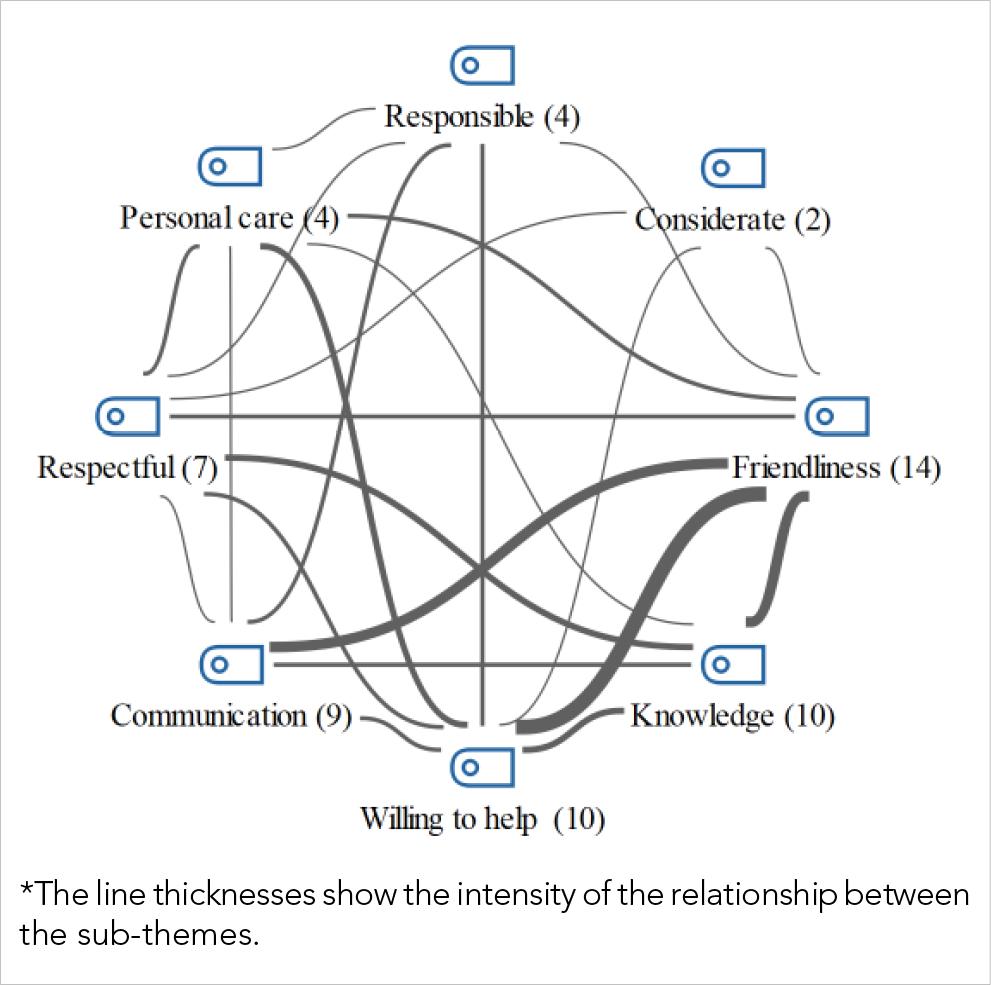

As seen in Figure 1, fitness centre participants evaluated the staff quality as a combination of eight sub-themes. These sub-themes are coded as “Friendliness”, “Knowledge”, “Willing to help”, “Communication”, “Respectful”, “Personal care”, “Responsible”, and “Considerate”.

In addition, when the relationship density of the codes was examined, it was revealed that the participants perceived the elements of “Knowledge-Friendliness” and “Communication-Friendliness” as the factors that most intensely affect the quality of the staff. They expressed their opinions on staff quality as follows:

Willingness to help-Friendliness (Associated code: 7): “I think it is important for the quality of the fitness centre that all the personnel, without exception, be willing to meet the member’s wishes and at the same time have a friendly interaction (P-3).”

Knowledge-Friendliness (Associated code: 5): “The most important factor is friendliness and diction. When it comes to the person who cannot communicate with the other person, this is like trying to run a horse without feet. As I mentioned in the previous questions, the level of knowledge of the trainers should also be good (P-10).”

Communication-Friendliness (Associated code: 5): “The employees of the fitness centre should have a good, friendly and positive personality in communication. This feature is indispensable for businesses as they are in the service sector (P-15).”

Respectful-Knowledge (Associated code: 3): “Must be able to meet the information needed by the members, and have a sincere and respectful approach (P-7).”

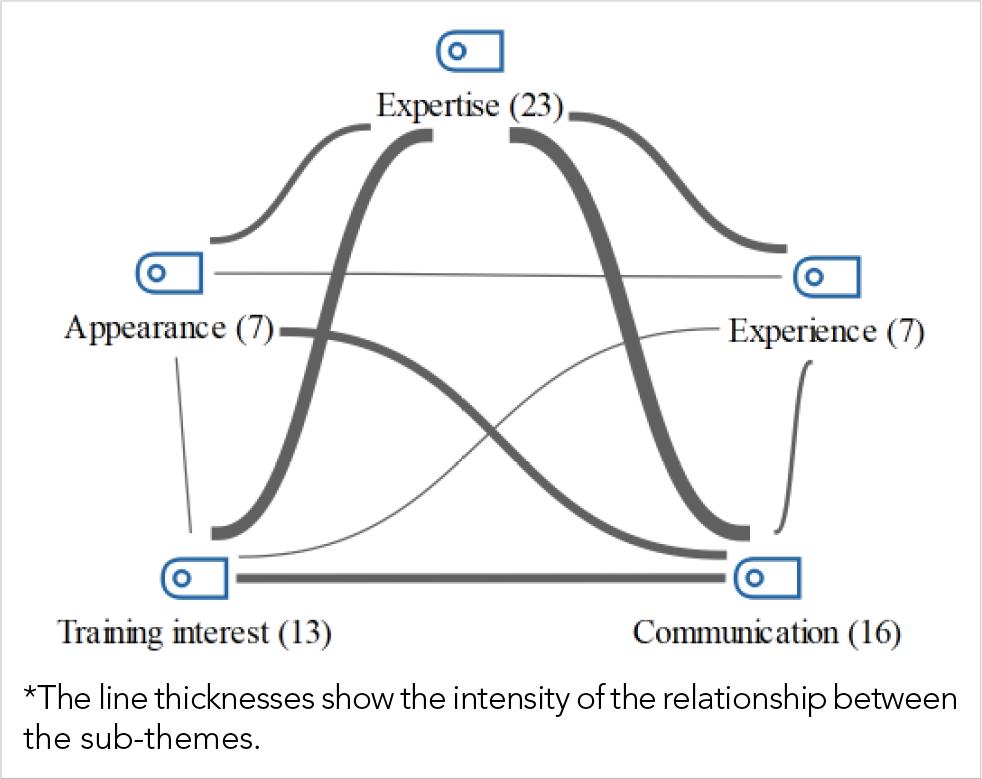

As seen in Figure 2, fitness centre participants evaluated the instructor quality under five different elements. These elements are coded as “Expertise”, “Communication”, “Training interest”, “Experience”, and “Appearance”. In addition, when the relationship densities of the codes were examined, it was revealed that the participants considered the “Expertise-Communication” and “Training interest -Communication” elements as the most intense factors affecting the quality of the trainer. They expressed their opinions regarding the quality of the trainer as follows:

Expertise-Communication (Associated code: 13): “If they have sufficient knowledge, skills and experience in his field, they can design personal workout programs considering personal differences, and if they can direct by considering the request of the member and the deficiencies of the trainer, they are qualified trainers (P-1).”

Training interest-Communication (Associated code: 8): “Trainers must be open to innovation, constantly educating themselves, strong in communication with people, and appealing to the eye in terms of health and appearance (P-6).”

Communication-Appearance (Associated code: 7): “Qualified trainers are people who have a proper physique that gives an athletic appearance, and also have coaching qualifications, for example, their diction and rhetoric must be absolutely decent because they will be in constant communication with people … (P-10).”

Expertise-Experience (Associated code: 7): “If fitness trainers have the experience related to their job and the qualification certificates given to them in return for this experience, and if they can convey this knowledge to them in accordance with the needs of the members, they are qualified (P-13).”

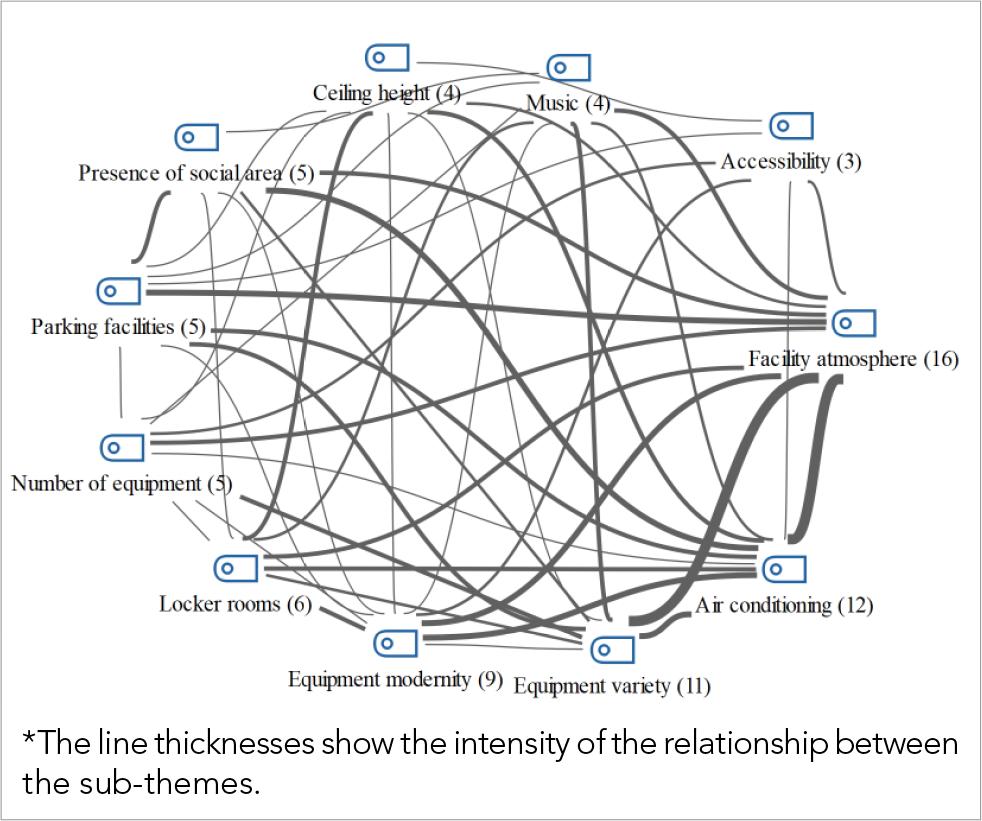

As seen in Figure 3, fitness centre participants considered the physical environment quality as a combination of eleven different elements. These elements are coded as “Air conditioning”, “Facility atmosphere”, “Accessibility”, “Music”, “Ceiling height”, “Presence of social area”, “Parking facilities”, “Amount of equipment”, “Locker rooms”, “Equipment modernity”, and “Equipment variety”. In addition, when the relationship density of the codes was examined, it was revealed that the participants see the factors of “Facility atmosphere-Air conditioning”, “Facility atmosphere-equipment variety” as the most intense factors affecting the physical quality of the fitness centre. They expressed their views on physical environment quality as follows:

Facility atmosphere - Air conditioning (Associated code: 8): “Whether a fitness centre is physically qualified or not is related to its location, being easily accessible, the size of the gym and adequate lighting (P-2).”

Equipment variety - Facility atmosphere (Associated code: 8): “Being a quality fitness centre in terms of physical elements means having the necessary number and variety of equipment for cardio, strength and group workout. In addition, the training areas in the centre should be of sufficient width and the members who are there at the same time should be able to train comfortably (P-3).”

Equipment variety - Air conditioning (Associated code: 5): “It is important to have richness in terms of sports equipment and wide and comfortable working areas. In addition, the fact that the fitness centre is bright, accessible and has a balance of price/service and sound/silence in the use of music gives the fitness centre quality (P-17).”

Equipment modernity-Facility atmosphere (Associated code: 4): “Having modern equipment, being large, spacious, and centrally located gives the fitness centre quality (P-11).”

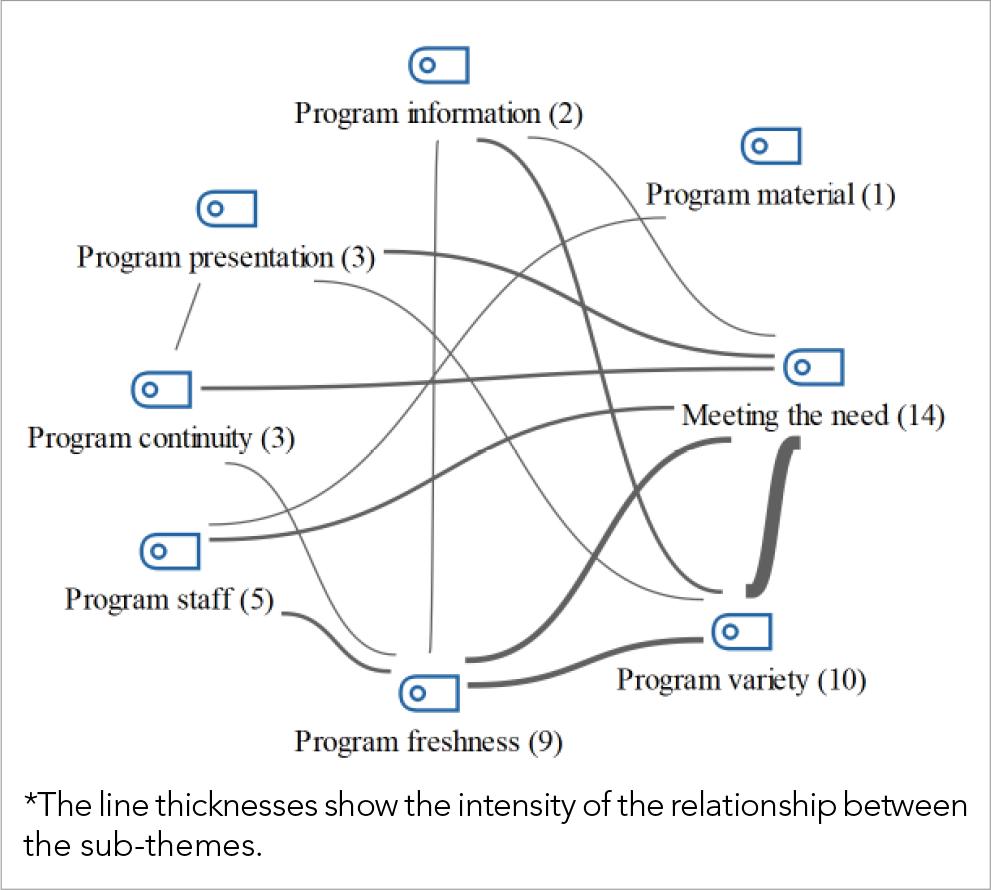

As seen in Figure 4, fitness centre participants evaluated the quality of the program as a combination of eight different elements. These elements are named as “Meeting the need”, “Program variety”, “Program freshness”, “Program staff”, “Program continuity”, “Program presentation”, “Program information”, and “Program material”. In addition, when the relationship densities of the codes were examined, it was revealed that the participants saw the elements of “Meeting the need-Program variety” and “Program freshness -Meeting the need” as the factors that most intensely affect the fitness centre’s program quality. They expressed their views on program quality as follows:

Meeting the need-Program variety (Associated code: 8): “The programs of fitness centres should be diversified in order to meet the demands. For example, if I want to lose weight, there must be a fitness program for it (P-3).”

Program freshness-Meeting the need (Associated code: 3): “Programs must be current and appropriate for the training objectives of the person. Current training types such as crossfitt, zumba, and spinning can be included (P-14).”

Program freshness -Program variety (Associated code: 3): “Diversity, that is, a wide range of up-to-date services should be available. Timing, in other words, the start and end of the program on time is also an important issue (P-17).”

Program freshness -Program personnel (Associated code: 2): “First of all, lessons should be held in the presence of an expert trainer. In addition, it should be with lessons that are innovative and brings out continuous improvement and awareness (P-9).”

DISCUSSION

Existing studies on quality in fitness centres conclude that research should continue from the consumer’s point of view and from different types of methodologies (García-Fernández et al., 2020; Loranca-Valle et al., 2021; Polyakova & Ramchandani, 2020). The main findings of this study have shown the importance for consumers in terms of the quality of the trainer, the quality of the physical environment and the quality of the program. In particular, in the context of the qualitative paradigm, sub-themes of personnel, trainers, the physical environment and program quality were determined, and then the relationship intensities between these sub-themes were ascertained. We distinguished the quality of staff into eight sub-themes: “Friendliness”, “Knowledge”, “Willing to help”, “Communication”, “Respectful”, “Personal care”, “Responsible”, and “Considerate”. The most intense relationship among these sub-themes was between “Willingness to help-friendliness”. Considering these findings suggests that whether the staff have the knowledge, are willing to help and are friendly is the most prominent factor that determines the quality of the fitness centre’s staff. Here, it turns out that fitness members attach importance to a friendly staff above all else. In other words, fitness members describe employees who are happy to see themselves as qualified (León-Quismondo et al., 2020). McMillan (2012) reported that one of the ten precursors of quality service in fitness services is friendly employees. At the same time, he defined the friendly, knowledgeable, helpful, responsible, polite and respectful behaviour of the personnel as the features that positively affect the quality of the fitness centre (Lam et al. 2005). Chang et al. (2005) found that staff behaviour affects the perception of staff quality. Xu et al. (2021) and Riseth et al. (2019) identified staff support as the reason why long-term members keep the fitness centre. These results contribute to the literature and support the findings of this study. We distinguished the quality of the instructor into five sub-themes: “Expertise”, “Communication”, “Training interest”, “Experience”, and “Appearance”. The most intense relationship among these sub-themes was between “Expertise-Communication”. Based on these findings, we can say that the expertise and interaction of fitness trainers will give them quality, as stated by Xu et al. (2021). Instructors play an important role in achieving their sportive goals. An important part of this role is expertise. For this reason, fitness trainers should be closely interested in information that includes both physical activity areas and beyond (Gavin, 1996) because this feature is an important element in their quality perception (Afthinos et al., 2005; Glaveli et al., 2021; Yildiz et al., 2021).

Afthinos et al. (2005) identified one of the most important dimensions of the quality of fitness centres as “professional knowledge”. Chang and Chelladurai (2003), who conducted one of the studies to evaluate the service quality of fitness centres, stated that “task interaction” is a dimension of quality. At the same time, many studies have underlined the importance of interaction quality for the success of service businesses (Ekinci & Dawes, 2009; Glaveli et al., 2021; Gremler & Gwinner, 2000). These findings emphasise the sub-elements of trainer quality and are in line with our research.

We distinguished the quality of the physical environment in eleven sub-themes: “Air conditioning”, “Facility atmosphere”, “Accessibility”, “Music”, “Ceiling height”, “Presence of social area”, “Parking facilities”, “Amount of equipment”, “Locker rooms”, “Equipment modernity”, and “Equipment variety”. The most intense relationship among these sub-themes was between “Facility atmosphere-Air conditioning”. Based on these findings, we can say that the “Facility atmosphere” and “Air conditioning” sub-themes make the physical environment quality of a fitness centre of a higher quality. Participants think that the variety of equipment in a fitness centre and the ideal air conditioning features, such as ambient temperature, humidity, ventilation, and pleasant atmospheric elements, such as decor, layout, and interior design, are facility aesthetics which will make that facility physically be of high quality.

The physical environment of the fitness centre is an integral part of promoting physical activity. Fitness centres are largely based on the physical environment of their services. Therefore, the competencies offered by the physical environment to meet customer expectations are important (García-Fernández et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2016; León-Quismondo et al., 2020). One of them is the facility atmosphere (Oztaş et al., 2016). This includes many features, such as the facility design and ambient condition. All these features affect the quality perceptions of the participants (Chang & Chelladurai, 2003; Cheung & Woo, 2016; Howat et al., 1996; Ko & Pastore, 2005). These studies are in parallel with our research.

We distinguished the quality of the program into eight sub-themes: “Meeting the need”, “Program variety”, “Program freshness”, “Program staff”, “Program continuity”, “Program presentation”, “Program information”, and “Program material”. According to the results of the research, the participants think that the “meeting the need-program variety” features of the program will give it quality.

The program quality dimension indicates the purpose of the fitness centre members coming to these centres and the content and quality of the programs and activities offered to them in these centres. The features of meeting the needs of fitness programs are related to creating programs suitable for members. For this reason, it is important for a fitness centre to plan programs in which members can achieve their sportive goals (De Farias et al., 2021). Participants’ views consider shaping the contents of the programs in the club in accordance with the objectives as the most important program quality element. For this reason, it is important for fitness centres to consider meeting the needs as their primary goal in the program that they include in the fitness centre. At the same time, as stated by Eskiler and Altunışık (2021), the diversity of the programs and activities offered in the fitness centre, in other words, the fact that the programs are up-to-date following the innovations, are important for the fitness participants to perceive the programs as being of high quality.

The results of previous studies on the quality of the program are similar to the results of this study. For example, Afthinos et al. (2005) identified one of the most important dimensions of the quality of fitness centres as “Convenient schedule”. Chang et al. (2005) identified “comprehensiveness/diversity of the program” as a sub-dimension of program quality. Lam et al. (2005) evaluated the variety and appropriateness of the program as factors affecting the quality of the program. Thus, it can be said that the results obtained in this study and previous studies are in parallel.

CONCLUSIONS

In this research, sub-themes of personnel, trainers, the physical environment and program quality, which have until now been put forward as sub-dimensions of quality by certain researchers, were determined, and then the relationship between these sub-themes was established intensely. The results of the research revealed that quality dimensions such as personnel, trainers, the physical environment and program quality have many more sub-themes in the context of the qualitative paradigm.

Undoubtedly, the coding frequencies of the sub-themes and the intensity of the relationship between the two themes show the elements that we should pay more attention to in terms of personnel, trainers, the physical environment and program quality. In summary, when we evaluate the research, it is necessary to give importance to quality sub-themes such as Friendliness and Willing to help for the personnel quality, and expertise and communication for the instructor quality, The facility atmosphere and Air conditioning concern the physical environment quality, Meeting the need and Program variety correspond to the program quality, and these elements are important for members. It should not be forgotten that they may affect the perceptions of quality more.

Limitations and future investigations

As in many studies, this study has some limitations. One of them is that the process was conducted with a qualitative research paradigm, and the relationship densities between the codes reflect the common view density of the participants. Since the findings are individual interviews, they cannot be generalised. For this reason, future research can achieve a deeper understanding of the relationships by using quantitative or mixed methods. Apart from this, when the literature is examined, there are limited studies on the relation of fitness centre quality elements (personnel, general quality, output quality, and the physical environment quality). Each element defined in fitness centres’ service quality sub-dimensions can be included in other studies. Researchers can compare high- or low-priced fitness centres in these studies. Whether the intensity of relationships changes in fitness centres in different price segments can be examined. Therefore, possible research to be carried out in the future will reveal more in-depth knowledge about which features fitness centres members evaluate as being of quality.