Introduction

Dandy-Walker malformation (DWM) is a complex malformation involving the cerebellum and the posterior fossa, in which there is a developmental anomaly of the cerebellar vermis and a failure of the normal fourth ventricle closure1), (2. This is a rare diagnosis, with an incidence of 1:30.000. (3 Among the most common ultrasound findings, there is an enlargement of the posterior fossa with an upward displacement of the tentorium, a cystic dilatation of the fourth ventricle and a variable degree of hypoplasia or aplasia of the cerebellar vermis4. The diagnosis of vermis rotation and elevation of the tentorium can be facilitated by finding median planes (sagittal), which is easily obtained by transvaginal ultrasonography in cephalic presentations4,5. Conditions affecting the posterior fossa, such as Blake’s pouch malformation and DWM can be distinguished by measurement of the brainstem-vermis (BV) angle. This angle is obtained by drawing a line tangentially to the dorsal aspect of the brain stem and a second line tangentially to the ventral contour of the vermis. It increases with increasing severity of the condition and angles greater than 45 degrees strongly suggest DWM5.

In addition, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is usually performed to confirm the diagnosis and to investigate associated anomalies2. The prognosis depends on associated structural anomalies, the degree of the vermis agenesia and the presence of chromosomal aneuploidy or genetic syndromes, with an estimated global mortality of 15% and with neurodevelopmental complications in 70% of cases6. There are many comorbidities associated with DWM. In a systematic review, approximately one-third of the patients had a chromosomal abnormality or a syndrome6. Thus, the prenatal diagnosis is extremely important in order to inform the parents about the prognosis to allow a medical interruption of pregnancy if requested.

Noonan Syndrome (NS) is a common autosomal dominant disease and it is caused by mutations in multiple genes encoding components of the RAS/MAPK pathway. This syndrome is characterized by short stature, characteristic facial features, congenital heart disease and variable developmental delay7. There are cases reported of NS associated with chiari malformation and hydrocephalus, but the incidence of neurological malformations is unknown7,8. However, NS rarely presents with evident neurologic manifestations and most adults have mild cognitive deficits7,9. Prenatal features are nonspecific and prenatal diagnosis of NS is usually made when there is an affected parent or when there is an enlarged nuchal translucency in first trimester or a cystic hygroma in the second trimester10.

The association between DWM and NS was only recently reported in one case of NS with the RRAS2 pathogenic variant p.Q72L9. Another study reported a DWM diagnosis in one particular case with de novo missense mutations in PPP1CB, a disease with similar phenotype as NS with loose anagen hair11.

Case report

A 22-year-old primigravida was referred to a prenatal consultation at 22 weeks of gestation due to the detection of a posterior fossa anomaly during her routine second-trimester scan. Her medical history was irrelevant and the male progenitor of the fetus and his mother had a diagnosis of NS, both with normal neurological development.

There were no records of first trimester obstetric assessment and that was the first sonographic evaluation. The detailed transabdominal ultrasound revealed only anomalies confined to the posterior fossa of the brain. On axial views, the cerebellar vermis was not identified and the posterior fossa was enlarged and it had a triangular shape. (Figure 1) Transvaginal ultrasound was performed in order to obtain sagittal planes ant it revealed a hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis, with rotation of the tentorium, with a BV angle greater than 45 degrees. These alterations were also seen in sagittal views at abdominal ultrasound at 30 weeks of gestation. (Figure 2)

Figure 1 Transabdominal ultrasound performed at 22 weeks of gestation, axial view. The cerebellar vermis is not identified and the posterior fossa is enlarged and it has a triangular shape.

Figure 2 Transabdominal ultrasound performed at 30 weeks of gestation. Median section of the fetal brain showing a large cisterna magna with a small and rotated vermis and elevated tentorium and torcular, with a BV angle of 85 degrees.

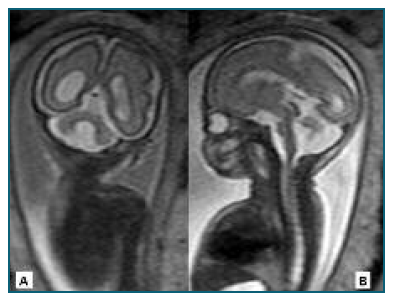

Genetic analysis was made by Array-comparative genomic hybridization (array-CGH), after amniocentesis, which didn’t show any alteration. Type 1 NS, PTPN11 variant (missense variant c.5C>T(p.Thr2Ile) in heterozygosity in PTPN11 gene), the pathogenic variant identified in the affected family members, was investigated and the fetus had the same mutation. An MRI at 25 weeks confirmed the sonographic findings together with hypoplasia of the cerebellar hemispheres and an asymmetry of the lateral ventricles, the right one with 11.4mm. (Figure 3) Additionally, persistence of the left vena cava and a small ventricular septal defect were identified in fetal echocardiography. The severity of the brain malformation and the poor prognosis were explained to the couple in a multidisciplinary-joint consultation with Obstetrics, Pediatrics and Genetics. Medical interruption of the pregnancy was refused and parents chose to maintain pregnancy surveillance. Neurologic prenatal findings remained unaltered throughout the pregnancy and the fetal growth was in the 2nd/3rd percentile.

Figure 3 Cerebral MRI performed at 25 weeks of gestation. There is an agenesis of the inferior portion of the cerebellar vermis with a superior rotation of the superior portion of the vermis and the tentorium, together with hypoplasia of the cerebellar hemispheres and an asymmetry of the lateral ventricles, the right one with 11.4mm. A - Coronal view. B - Sagittal view.

At 39 weeks, the primigravida was admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of premature rupture of membranes. A cesarean section was performed by breech presentation and a female infant was born with 2290g and an Apgar index of 6/8/9 in the first, fifth and tenth minutes respectively. Physical examination of the neonate revealed a long forehead and dolichocephalic skull, with normal head circumference and weight and height below the 3rd percentile. Further evaluations revealed frontal erythema, sparse hair, frontal bossing, sparse eyebrows, hypertelorism, flattened nasal bridge with anteverted nostrils and low-set ears with posterior rotation. The prenatal findings were confirmed by postnatal cerebral MRI which additionally revealed chronic supratentorial hydrocephalus. (Figure 4) The head circumference was in the 85-97 percentile, with no indication for neurosurgery treatment. The infant is currently 15 months and she has an axial hypotonia, with no control of the pelvis, no strength in the lower limbs and poor weight development below the 3rd percentile. She is under hospital surveillance in Neurosurgery, Cardiology, Neurology, Otolaryngology, Physiatry and Genetic consultations and she was referred to a national association that was created with the purpose of qualification, rehabilitation and social integration of children with multiple disabilities.

Discussion

This is the first reported clinical case of DWM associated with NS with PTPN11 mutations. Although the neurological development of the infants with NS syndrome is generally normal, DWM is associated with neurodevelopmental complications in 70% of cases, as indicated above6. In this case, the association with DWM was the most likely reason for the poor neurological development.

This case highlights the importance of sagittal planes in neurosonographic evaluation, which allow the assessment of the cerebellar vermis with prognostic implications. In this way, sagittal planes are important to make differential diagnosis with other posterior fossa abnormalities, such as the persistent Blake’s pouch cyst, an abnormality with better prognosis once the vermis has normal anatomy and size.

On the other hand, this case report allows to correlate prenatal findings with clinical and other neonatal evaluations, such as neonatal MRI. This is of special importance regarding that DWM generally motivates a medical termination of pregnancy and, for this reason, reports of neurological development are rare when it is performed a prenatal diagnosis.