Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.8 no.1 Lisboa jan. 2014

A clearer picture: Towards a new framework for the study of cultural transduction in audiovisual market trades.

Enrique Uribe-Jongbloed*, Hernán David Espinosa-Medina**

*Universidad de La Sabana, Colombia

** Universidad de La Sabana, Colombia

ABSTRACT

This paper presents a theoretical and methodological revision which clarifies and organizes the concepts on the trade of audiovisual products between different cultural markets. It explores the concept of cultural proximity (Straubhaar, 1991) and the latest discussions on cultural translation (Conway, 2012) and cultural universals and lacunae (Rohn, 2010, 2011). After analyzing the various academic perspectives, the paper proposes a new framework, which defines more clearly the terminology, thus making a tool for comparative studies of audiovisual trade. This framework is divided into four aspects: market, product, people and process. Previous concepts are narrowed down and new concepts are developed to fill in the conceptual gaps.

Key-words: Cultural proximity; Cultural translation; Cultural transduction; Audiovisual markets; Flow and contra-flow.

Introduction

The increase of audiovisual trade world-wide is undeniable (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2005). For instance, the combined 2005 revenue of the six main media corporations1 totaled more than USD 300 billion something exceeding the 2006 GDP of all but 20 countries in the world (Bruner, 2008, p. 412) and the 2011 format trade of TV programs has been estimated to reach 3.1 billion (Chalaby, 2012). The elevated costs of local media production make it very appealing for media companies to find markets beyond their borders (Rohn, 2004). In that process of expanding audiovisual markets, academics the world over have tried to point out the specific mechanics that take place, coining a very specific set of concepts to define the elements of international audiovisual trade. Straubhaar's (1991) revision of the media imperialism concept sets the base for a discussion on the relationship between the culture of the place where an audiovisual product is created and its broadcasting or distribution elsewhere. In over twenty years, both he and other academics have expanded, criticized, and complemented the conceptual tools to classify and organize studies about the transnational trade of audiovisual cultural products.

Methodology

The relative currency of the topic and a constantly changing environment have made a concise vocabulary difficult to coin. This paper presents a literary review of over forty articles and papers from the last twenty years. It explores the concepts, clarifies them and provides a framework for comparative studies. Starting from globalization, a very contested concept in its own right, the following pages bring together the development of the terminology used in academic debate of global audiovisual market trade. This becomes a worthy endeavor since "the complex relations between local, national, regional, and international production, distribution, and consumption of media texts in a global context further complicate the globalization discourse" (Thussu, 2008, p. 162), and a more concise vocabulary becomes fundamental to further develop this academic field.

Globalization and the market for audiovisual cultural products

Globalization is a catchword that started to emerge in the 1990s to define a phenomenon of increasing international interaction. As a concept, it has been applied loosely and in contradictory ways (Robertson, 1992). Most definitions include what it is, its consequences, and what should be done about them (Rantanen, 2005). However, although there is no single theory of globalization that commands common assent ... there is a certain banal agreement that globalization means greater interconnectedness and action at a distance (Sparks, 2007, p. 126).

Sánchez-Tabernero (2006) argued that globalization stems from a political development, the fall of the Berlin wall; an economic development, the creation of the WTO; and, a technological achievement, the Internet. Those three factors, he pointed out, opened up the markets and the possibility for audiovisual exchange in ways not achieved before.

Thus, globalization is an interplay of increased exchange (of people, goods, images, capital, etc.) and the development of a conceptual category of the whole globe as the phenomenological space of action (Inda & Rosaldo, 2008), which makes it easier for us to understand each other across cultural divides, but [which] also creates tensions between groups that were formerly isolated from each other (Eriksen, 2007, p. 13). Because of this increased international exchange and influence, globalization has also been considered as a factor altering the status of states, supposedly weakening them and enabling more access to power to supranational organizations, including NGOs and transnational corporations (Sparks, 2007). This is especially relevant in international communication exchanges, since globalization entails "the construction of a symbolic environment that reaches right around the globe and is organised, in very large part, by media [transnational corporations]" (Webster, 2006, p. 73). Although it would seem that such international market presence would undermine the power of nation-states, it does not imply their erasure as governing units of social and cultural aspects, because "nation-states, despite their multidimensional crises, do not disappear; they transform themselves to adapt to this new context" (Castells, 2009, p. 39).

The increasing exchange of audiovisual products world-wide has been presented as evidence of globalization (Castells, 2009; Sparks, 2007; Waisbord, 2004, p. 360). The flow of this exchange continues to stem predominantly from developed nations, despite the growth of regional markets (Sparks, 2007; Straubhaar, 2000; Thussu, 2010; Webster, 2006). In its study of the international trade of cultural goods, UNESCO (2005) demonstrates the growth in audiovisual media trade, claiming that the percentage of audiovisual trade, as part of the world-wide trade of all forms of trade of cultural goods, had doubled between 1994 and 2002.

With these facts in mind, Thussu (2010) defined two types of audiovisual flow: the dominant flow, mainly from the US, Western Europe and Japan to the rest of the world; and contra-flows, which included transnational flows between countries other than those in the dominant flows, and geo-cultural flows mainly stemming from diasporic producers or audiences broadcasting back into their place of origin, or from the place of origin into their new place of settlement. Globalization has expanded the market for the main players, but it has also provided new possibilities for certain minorities to develop their own niche production and create their own cultural links to generate alternate media spaces. The development of the New Media Nation concept for indigenous media (Alia, 2010) and the networks developed by Minority Language Media campaigners in Europe (Hourigan, 2004) are but two examples of this counter-current also promoted by globalization.

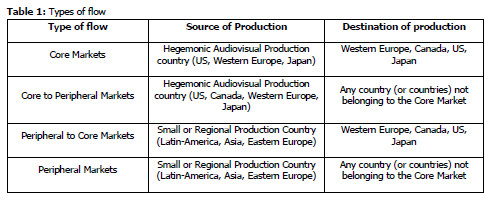

Thussu's (2010) conceptualization of the flows and contra-flows is problematic because different audiovisual trades cannot be classified clearly within his contra-flows category without considerable overspill between transnational and geo-cultural flows. Elsewhere, Uribe-Jongbloed (2013) has advocated for a clearer distinction into three types of flows, expanded here to the four following types (see Table 1).

According to this classification Hollywood's production is both a Core Markets, and a Core to Peripheral Markets exchange (Bruner, 2008; Fu & Govindaraju, 2010; Straubhaar, 2010; Thussu, 2010), which is also the case of TV format sales (Chalaby, 2012). The Peripheral Markets scenario includes indigenous amateur video exchanged at specific film festivals or events (Salazar & Cordova, 2008) or the success of Nollywood (Haynes, 2012), and the Peripheral to Core Market flow is evidenced, among others, by the success of Latin American telenovelas the world over in general (Martínez, 2005), or in Eastern Europe (Salgueiro, 2004), and Israel (López-Pumarejo, 2007), specifically.

Although the phenomenological space might have become global, "one of the main limits on globalization in media and culture is that relatively few people have a primarily global identity" (Straubhaar, 2007, p. 6) and despite the growing global identity, "the globalization of television economics has not made national cultures irrelevant" (Waisbord, 2004, p. 379). As pointed out above, other identity issues such as language, tradition, world-view and geographic location remain fundamental in most people's sense of identity. Because of this strong local identity, there is an increase in linguistic, ethnic, and indigenous minority media (Browne & Uribe-Jongbloed, 2013).

As signaled by Sánchez-Tabernero (2006), the technological breakthrough of the Internet also created a new space for mediation of audiovisual products. Youtube, vimeo and cuevana, have become household names for spaces of consumption of both legally and illegally uploaded audiovisual content, whether consumer-generated or copied from original industrial sources. This is evidence of a global participatory culture (Deuze, 2006) that offers another type of exchange space alternate to the usual market flows. It has to be borne in mind, however, that despite the hype of this participatory culture of the Internet and the concept of the digital age as a description of our time, many parts of the world remain yet to be connected to the information superhighway, and their access to a global information network is nothing but a fallacy (Ginsburg, 2008). Flows, then, remain uneven in their market distribution due to the same technological, economic and political factors which prompted globalization.

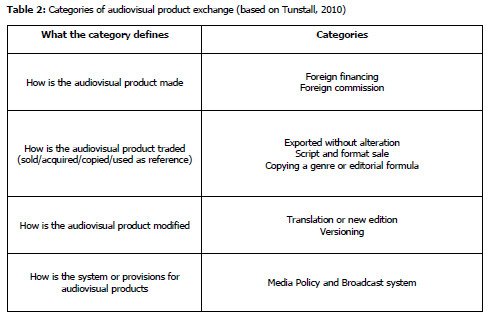

Audiovisual exchanges between countries have various forms of trade and interaction. Tunstall (2010) classified the forms of audiovisual product exchange in eight categories. They describe the way in which an audiovisual product is either made, traded, and modified after acquired, or how the whole system is established and defined (see Table 2).

Although all categories, except foreign financing, imply some form of localizing the audiovisual product – that is to say, of making the local culture engage with the product before its presentation or broadcast – undeniably these products are adapted and framed for the local audiences from all possible perspectives.

Iwabuchi (2010) argues that localization takes place at the same time as the local industries aim to have a larger impact on regional markets, and those countries with high production (such as Japan in his studies), try to expand their potential markets by selling audiovisual products to be adapted. This multinational exchange of audiovisual products becomes evidence of a globalized economy, and

considered from a business point of view, this development suggests the increasing integration of national television industries into a global television system. Yet, more than ever, television viewers seek to watch programs that look and sound familiar and speak to them about the world they know (Moran, 2009a, p. 52).

Moran (2009a, 2009b) highlights the facts that audiovisual products travel more commonly now from one country to another, formats are developed with customized versions for different audiences, new ways of interpreting and remixing creative material are developed every day, new ways of collaborative production collide and are transformed and the people involved in these processes require new conceptual tools to understand the framework that surrounds them all. Given this need, many academics have sought to clear the picture from different perspectives, each of them adding their own piece of the puzzle (Conway, 2012; Rohn, 2011; Singhal & Udornpim, 1997; Straubhaar, 2007; Wang & Yeh, 2005). We proceed to present those concepts and review them to create a more concise framework, a clearer picture.

The first term to examine and revisit in relation to our new vocabulary is cultural proximity. It has been used to help understand the way in which a product generated in a cultural market may be accepted within a different cultural market. However, this term has undergone various changes that have made its definition more complex throughout the years.

Cultural Proximity

To determine whether and how a foreign audiovisual product, especially in television, needs to be adapted in a different country or television market, Straubhaar (1991, 2007, 2010) developed the concept of cultural proximity.

This notion appeared for the first time in an article about an exploration of the concept of cultural imperialism (Straubhaar, 1991). In that context, the question regarding the theories of cultural imperialism were analyzed by Straubhaar under the scope of other concepts, such as Fiskes (2001) theory of the active audience, originally published in 1987; the concept of product life cycle (de Sola Pool, 1977; Read, 1976); and new evidence that came from Straubhaars previous research in Latin America. He pointed out that although it was clear that there was some form of dependence in audiovisual imports from stronger markets, as the theorists of cultural imperialism suggested, audience preferences also defined, to a certain extent, how products shifted from one market to another.

To understand how this shift and trade of products occur, Straubhaar (1991) coined the concept of cultural proximity to use as a tool to look at the different kinds of products that audiences prefer. By doing this there was a recognition of the notion of a heterogenic audience composed of different groups of people that share, to some degree, elements of cultural identity. As he would describe it, "beyond the structural relationships that the dependency literature leads us to examine, we must look at how media are received by audience as part of cultures and subcultures that resist change (p. 39). Since different countries have developed their own audiovisual industries, it would seem coherent to start exploring the notion of what people prefer by observing how do they consume the content developed in their own countries compared to that developed elsewhere. Through this observation, Straubhaar arrived to a first important concept: these audience preferences lead television industries and advertisers to produce more programming nationally and to select an increasing proportion of what is imported from within the same region, language group, and culture, when such programming is available (p. 39). This observation suggested that people that were part of a community related more easily to the content made by others culturally similar to them and, to a second degree, to those products made by people from cultural markets similar to their own.

Thus, the concept of cultural proximity serves as a way to demonstrate the contra-flow in media markets, making clear that "hegemony may not fully explain media preferences of audiences in the South. Nor may it always explain the choices Third World producers make when creating programming for their audiences" (Burch, 2002, p. 572).

Cultural Proximity beyond the Nation-State

After this first definition of the concept, the notion of cultural proximity developed thanks to the way in which La Pastina and Straubhaar (2005) came to rethinking cultural groups and the manner in which they were defined, expanding the initial analysis done by Straubhaar (1991) to include a sub-national or local level apart from the national and supra national levels (La Pastina & Straubhaar, 2005). This new point of view was that even when the nation-state is taken as a starting point in the definition of a community or cultural market, there are also factors, apart from place and language, that may determine a cultural group. As the authors point out:

Cultural proximity is based to large degree in language. However, besides language, there are other levels of similarity or proximity, based in cultural elements per se: dress, ethnic types, gestures, body language, definitions of humor, ideas about story pacing, music traditions, religious elements, etc.(La Pastina & Straubhaar, 2005, p. 274).

Building on the fact that cultural proximity can be observed in all of these aspects the authors pose the concept of multiple proximities and multi-layered cultural identities. In fact, it is through these elements that a more local, sub-national, level of proximity can be defined. They mentioned that

there are other notable factors that guide peoples choices and interests in culture such as television programs. These include the nature of various genres and their fit to specific cultures, the development of subgenres that divide broader audiences, and the maintenance of historical or interest ties between subgroups of larger cultures that may guide them away from dominant national television genres and programs (La Pastina & Straubhaar, 2005, p. 273).

These notions change the way of understanding cultural proximities. La Pastina and Straubhaar define cultural proximity, not as a stable relation between a culture and a product, but a changing way of seeing the relationship between two cultural markets. The authors develop this new point of view from the ideas taken from Iwabuchi (2000) and Martin-Barbero (1993), amongst others. This offered a new perspective of cultural proximity as a two-way relationship between markets.

Cultural Media Powers

Finally, the concept of cultural proximity defined in terms of a relationship between two cultural markets that may be part of the same nation-state, part of a geo-linguistic region or even close in terms cultural-linguistic groups (Straubhaar, 2007), and the fact that this relationship changes, leads to explore the notion of cultural media powers (Straubhaar, 2010).

Straubhaar (2010) realized that, thanks to the way markets change through time, some of the markets that were part of the periphery, in their dependence on other core markets to produce some audiovisual products, grow and transform themselves into important nodes of production and even come to dominate transnational markets. He cited in particular the cases of China, India and Brazil. Straubhaar looked at these markets as new cultural media powers and tries to understand their growth. As an analytical tool he uses the notions posed by Appadurai (1990), and looks at the change in the relationships between countries (financial, technological, ethno/migration, media, and ideology) to explain how many factors may influence the relations amongst countries. After analyzing the three cases he concluded:

It might be theoretically interesting, therefore, to think of emerging media and cultural powers as those who work first from a strong home base, either large or affluent or both. Secondly, it seems that emerging powers build next on an important regional or cultural-linguistic market base in which they are to some degree also dominant. Then, thirdly, we may see them emerging as truly global media or cultural export powers, reaching first to diasporas, then to more truly global audiences in the case of China and India, or moving directly to export as in the case of Brazilian television (Straubhaar, 2010, p. 259).

Use and criticism

Various authors have used this concept of cultural proximity to explain why certain media products are more readily accepted in other markets (see Brunner, 2008; Iwabuchi, 2004; Liu and Chen, 2004; Fu & Govindaraju, 2010; Waisbord and Jalfin, 2009). Their main argument has been the relative ease through which a certain audience receives a specific product or set of products from a different audiovisual market. Usually, they use the nation-state as the cultural sphere, thus presenting cases in which a product from one nation-state is broadcast or distributed in another one. However, despite the readiness to use the concept to classify certain audiovisual exchanges, some academics have criticized it from various perspectives.

Waisbord and Jalfin (2009, p. 59) have argued that although cultural proximity may be the reason why audiences prefer some content, as a conceptual tool it does not say much about how the products are localized. Davis and Nadler (2010) have argued that cultural proximity does not ensure market entrance, showing how a Canadian product was considered not culturally appropriate to a U.S. audience. Finally, Castelló (2010) has argued that cultural proximity goes beyond the national, linguistic or territorial identity, and even beyond the audience's interpretation of an audiovisual product, and the concept should refer instead "to the ability to establish hypernarrative links to recognizable stories (coming from both cultural consumption, knowledge and daily life experiences and shaped by discursive formations) and taken-for- granted meanings shared from inception (by professionals) to consumption (by viewers)" (p. 221). Whilst Davis and Nadler (2010) demonstrate that there are other market forces beyond cultural proximity to determine market access for audiovisual products, Waisbord and Jalfin (2009) and Castelló (2010) seem to be at odds with one another in the use of cultural proximity as a concept. Whereas the former claims the concept does not tell us about the process of making a product culturally understandable, the latter assures that this is precisely what the concept entails. Thus, the problem in the use of cultural proximity as a framework is that it seems to refer to two things at once: a condition of a market in regards to another one - the reading from Waisbord and Jalfin -, and a condition of a product which seeks to be inserted into a given market - Castelló's view.

In order to disentangle the two, we propose here to keep cultural proximity as a definition of market condition in regards to another one - so to say, a relational condition -, and to use a different set of terminology for the product itself: namely our next conceptual tools shareability and cultural discount.

Cultural Shareability and Cultural Discount

La Pastina and Straubhaar (2005) introduce the notion on cultural shareability as a complementary concept to cultural proximity. The former concept is explored by Arvind Singhal and Peer Svenkerud (1994) and has been exemplified and further studied in relation to particular products along with the notion of pro-social entertainment (Singhal & Udornpim, 1997). What Singhal and Svenkerud (1994) mean by shareable programs is that the product itself includes components that make it easy to understand by audiences in different cultural contexts. As such, it becomes evident that shareability is a characteristic of the product, not of the market, in contrast to cultural proximity which is a characteristic defined as a relationship between different cultural markets.

If we defined this terms this way, it is clear why shareability complements cultural proximity. It allows the following hypothesis, that a given product created in a particular market may have a high level of shareability in those markets which have high cultural proximity to the cultural market where it was created. This direct relation is exemplified by Singhal and Udornpim (1997) in the case of Oshin, a soap opera created in Japan and positively accepted in a culturally close market like Thailand. In that particular case, the authors underline that both audiences, the Japanese and the Thai, seem to identify with many of the same characteristics in the program. At this point another notion is introduced to complement shareability, the concept of the archetypes established by Carl Jung. These archetypes are considered as elements that enhance the shareability of a product, since they are, by definition, part of the collective unconscious worldwide.

In terms of developing culturally shareable programs some authors issue a word of caution, hoping to point out the difficulties that may arise from the development of this kind of products (Singhal & Svenkerud, 1994). In particular, it is important to understand that total shareability is not possible; that by trying to achieve high levels of shareability there might be difficulties and limits to the level of specificity and localization of the products, narrative, characters, etc. that someone may hope to attain; and that shareable products may conduct to a homogenization of cultural values (Fu & Govindaraju, 2010).

However, efforts to create more shareable products may also represent a chance for smaller markets, especially in the developing world, since the creation of shareable programs can help in developing countries pool resources, fight common development problems, reduce their dependence on imported programming, and promote regional and local interdependence (Singhal & Svenkerud, 1994, p. 26). In other words, creators have a chance of developing more and better products by joining their resources and by aiming to reach a larger, more divers, audience.

But shareability is just one of the characteristics that we have to define in terms of a product and its relationship to cultural markets. There is another characteristic that can help us understand the way products are negotiated and introduced to new contexts: cultural discount. It was defined by Colin Hoskins and Rolf Mirus (1988) as the value loss of a product when it is being considered for broadcasting, adaptation or other forms of modification in a new cultural context. The principal notion is that a product that was developed in a particular context will have its value diminished as it is introduced into a market in which the people lack the cultural capital to understand it or relate to it. Based on this concept, Lee (2006) argued that producers may find it advantageous to decrease the cultural discount of their products to gain competitiveness on the global market. He points out that reducing the cultural discount could be achieved by universalizing it. In other words, this means increasing its shareability.

However, Lee also points that trying to universalize a product may affect its reception in a local market, since it would be felt to be a product seemly void of cultural grounding. This is something that has been argued in the case of Hollywood productions, for instance, which tend to be made of "lowest-common-denominator themes scrubbed of cultural specificity" (Bruner, 2008, p. 353). Another point that must be taken into account is the fact that cultural discount added to the different sizes and capabilities of different markets may tip the scale in favor of the bigger, more robust markets which may take a larger advantage of their own markets to better finance their production and distribution (Hoskins, McFadyen, & Finn, 1994; Lee, 2006).

So although these two terms, cultural discount and cultural shareability, refer to two different characteristics of a product, it is evident that there is a relationship between them. Basically, if there is a high cultural shareability between a product and a market, the value of the product in that particular market would suffer from a smaller cultural discount than that of a product that has a lower shareability (Lee, 2006).

But how can we determine if a product has a high or low shareability? We would need to define the cultural elements that make a product more or less appealing in a different cultural market.

Cultural Universals and Lacunae and the process of de–, a–, and reculturalization

To classify the aspects that make a product more or less shareable, Ulrike Rohn (2004, 2010, 2011) presents an interesting set of concepts that work as tools which may help researchers come closer to answering this question. What she tries to provide is a description of the types of elements that determine the shareability or cultural discount of a product. Rohn does so by providing a set of new concepts to the vocabulary that has been addressed. The first notion is that of cultural lacunae, which she defines as

the gaps or mismatches between the cultural baggage of the media producers, which influences the topics and the style of the content, and the cultural baggage of the audiences, which influences the kind of media content they select, how they understand it and to what extent they enjoy it (2011, p. 633).

In other words, lacunae appear in the space between the content and the audience when the audience is unable to relate, in one way or another, to elements of the content. These lacunae may be of three distinct types: content lacuna, capital lacuna or production lacuna. Each of these kinds of lacunae points to a possible gap that may decrease a products shareability.

A content lacuna is a gap that makes a content appear culturally distant and even irrelevant. These lacunae may be more evident in the case of very low cultural proximity between the cultural market context of the original product and the market into which a producer wants to insert the program. In essence, these lacunae appear when audiences do not even consider the elements of the program valuable, not understanding the core ideas, concepts, characters or their motivations, upon which it is based. An example of a content that may make obvious content lacunae with audiences is a local news program of a geographic area other than the audiences' area.

The second type of lacuna is the capital lacuna. This lacuna is found when the audience understands and values the program, but does not have the cultural capital to understand the elements presented in the text. As Rohn (2010, 2011) clarifies, this lacuna is not a matter of appeal of the product for the audience, it may be that the audience wants to have access to the product and even feel related to it, but they might not have the tools to understand it. A clear example cited by the author is language. An audience may be interested in the content but the barrier generated by not understanding the language in which it was made creates too strong a hurdle for them to understand the content. Humor is another example, since many of the punch lines rely heavily on the language and its structure. Thus, comedies tend to have more lacunae, because humor is "highly culturally specific. It does not easily travel across cultures or survive the translation process" (Lee, 2006, p. 274).

Finally, there is a gap that can appear when the characteristics of a certain genre or format are not comprehensible to the audience. These characteristics, that can be aesthetic or related to the formatting of the content, are what Rohn (2011) calls production lacunae. In the case of production lacunae, the program is made in a way which the local market does not present, its aesthetic elements are different than what the local market provides or accepts, or the quality and style are not usually broadcast in their media.

Rohn's lacunae are conceptual categories to explore in given products, to determine the level of cultural discount to be expected. But there are other kinds of characteristics of the product that may signal higher shareability. Rohn defines them as cultural universals. Similar to lacunae, the universals are presented in three distinct types: the content universals, the audience-created universal and the company-generated universal.

Content universals are those that make the content relatable to different cultures. An example of what some authors have signaled that might work as a content universals are the values and archetypes found in pro-social content (Singhal & Udornpim, 1997). Therefore, it can be argued that the content universal aspect of Yo soy Betty, la fea, which made it an international success, was the image of the undervalued smart-but-unattractive young woman in a clerical position (Rivera-Betancourt & Uribe-Jongbloed, n.d.), basically the story of the ugly duckling.

Audience-created universals are those that rise from the meaning that people in a particular market may imprint on a product. This meaning stems from those peoples own cultural understandings and capital and may be able to come to the fore due to the polysemic character of content (Fiske, 2001). This is what Lee (2006) refers to as local reception. A particular audience-created universal could be identified at what Rohn (2011) calls desired proximity based on the notion posed by Koichi Iwabuchi (2002). This is the idea that people may relate to a content because of they have a cultural desire towards what the content represent.

Finally, Rohn (2010, 2011) proposes the notion of company-created universals. These are the universals that media companies generate by the positioning of the product, be it by positioning it as a product that may fill a gap in the local offer or by positioning in such a way that the lacunae of the product are downplayed in front of the audience. The four mega formats (Chalaby, 2012) seem to fit in rather well with this description, making themselves known as a style in their own right, and creating many copies from their development. Another example of this form of universal is revealed when a producer from a foreign market has the capability to flood a local, national or regional market with a particular kind of products, be it products of a kind that is absent in said market or products that already exist in it but have lesser production values than the ones that the foreign producer may afford. In those cases one could argue that the corpus of products brought from the outside by this outlandish producer, or group of producers, insert a new discourse into that particular culture (Castelló, 2010). When the audience accepts and gets used to this discourse their proclivity to accept new products that fit into the discourse rises, for they become familiar to those kinds of products and thus identify them as a universal. So if a product has an affinity with a company implanted discourse that would be a company-created universal dependent on a characteristic that could be defined as discourse proximity.

After a decision has been made about the inception of a given cultural product into a different cultural market, be it because the people involved in the decision feel that the product has a high level of shareable components with the new context, that the receiving context has placed a good value on the product they are about to experience because of the shared cultural capital to understand it, - hence, low cultural discount -, the question of what elements should remain as part of the product and which should be changed arises. Understanding the process of transforming a cultural product for its integration into another market becomes as useful as understanding the elements that make a product shareable or not.

Wang and Yeh (2005) address this issue by studying how a product may change from a particular tradition into the needs of a larger or different market. In this study the first process that the authors identify is one in which

all of the elements that are culture specific, including those that are ethnic, historical or religious, that create barriers to intercultural reception or are deemed unfit for a new presentation style, may be contained in a familiar narrative pattern that not only plays down cultural differences, but also guarantees comprehension across viewer groups (Wang & Yeh, 2005, p. 178).

This is called deculturalization and can be described as the process through which there is a reduction of the elements that could affect the shareability of a product, and a later modification through the use of more commonly known narrative elements or structures, be they global or local. After the product has been freed of as many culturally dependent elements of the content, - by removing potential cultural lacunae -, it becomes an acculturalized product. An acculturalized product may be the end in itself, in the case of very universalistic, but culturally empty, Hollywood productions (Bruner, 2008), yet it usually is an in-between stage for television programs or formats.

The product is then altered again, and the process continues by filling the gaps with the local content, suitable to the destination's cultural market. This third and final stage is called reculturalization. It includes the modification of elements from the original, such as removing references to sexual topics in countries where this is considered rude and transforming them into clean romantic interest (see Waisbord and Jalfin, 2009), or adaptation by substitution in the case of The Teletubbies and The Beakman's World as they were adapted in Catalonia (Agost, 2004, pp. 76–77). Reculturalization is achieved by removing elements which produce capital lacunae, whilst keeping content universals.

Now that we have established the concepts related to the product itself, including shareability and cultural discount, as well as a description of the process of de-, a-, and reculturalization, the following step would be to define the people behind these processes.

Cultural transductors: the scout, the merchant, and the alchemist

People involved in the mediation process of cultural products are often called cultural intermediaries. Cultural intermediaries are "individuals and organizations that are concerned with the communication and distribution (i.e. meaning transfer) of the cultural product to consumers" (Venkatesh & Meander, 2006, p. 13), and include both those in charge of marketing a product developed by the local industries, the cultural gatekeepers, and those who are concerned with the promotion of a given cultural product within a different market from the one it was created in, the cultural transductors. We have preferred the term transductor, because it clearly defines the cultural intermediary as working between cultures, and distinguishes it from the cultural gatekeeper (for instance, a local art critic) who works at the local level and in regards, almost exclusively, to local cultural products.

The cultural gatekeeper has been described as an intermediary position in the culture market, through which certain institutions or individuals redirect attention to cultural products (Venkatesh & Meander, 2006, p. 18). There is reference to cultural gatekeepers in a book chapter about the Singapore audiovisual format market (Lim, 2004, p. 117) as players who engage in dialogue with broadcasters to define what product is selected for broadcast. They are working from within the market.

The cultural transductors, on the other hand, are those cultural intermediaries who work between cultural markets, rather than exclusively within them, and are in charge of the transduction process. If there is such thing as a hybridization or convergence process, or the de-, a-, and reculturalization described earlier, the cultural transductors are the people behind it, determining the form in which that selection and modification processes take place.

Bielby (2011) talks about this transductors by calling them cultural arbiters, "such as policy makers who determine availability of content or products from particular sources and audiences whose taste preferences influence producers and shape product trends" (p. 526). In her study she discovered that there are specifically assigned cultural arbiters in the U.S. television market, mainly trade journalists and critics of television products, who publish in trade journals that guide the industry choices for acquisition. However, "in the absence of designated professional critics or cultural arbiters in the world market, boundary spanners become product appraisers" (p. 536), so those involved in the trading fairs representing their own companies' interests, become at once critics, evaluators and traders of the audiovisual products. Kuipers (2012) also uses a different word when describing those involved in the international audiovisual trade fairs as "cultural intermediaries, mediating between producers and consumers and transnational and national fields... [t]hey are consumers to the producers; yet they are producers to other intermediaries such as programme managers, financial managers, translators, schedulers and public relations functionaries" (p. 582). But, as mentioned above, cultural intermediaries can be separated into those who work within local cultural markets and those who work between them. Conway (2012) refers to television production managers as cultural translators, when they import and adapt programming. He defines their job as those in charge of cultural translation, which "is a mode of participation in a semiotic economy where signs are exchanged for other signs, on a basis not of equivalence but of negotiation" (p. 587). Moran (2009b) brings up the word gatekeeping when he describes a kind of travelling producer, expert or specialist who negotiates the cultural concepts and mediates in the process of acquisition and adaptation. The travelling expert's job of "television gatekeeping is relatively recent, although the general type of cultural decision-maker has a longer pedigree" (Moran, 2009a, p. 43). Similarly, Waisbord and Jalfin (2009, pp. 59–60) use gatekeeping as the term to describe the work of adaptation and localization done by local audiovisual media producers.

As the cases presented show, the idea of the cultural transductor is present in much of the literature, despite the various ways in which it has been described. However, although the role of intermediary, mediator or negotiator is evident in all of the descriptions mentioned above, it would seem that the transduction process can be clearly divided in three different concepts.

The first of the concepts would be the scout. This travelling expert, in the words of Moran (2009a, 2009b), is in charge of discovering the audiovisual product which might be easy to acquire to be broadcast, be it as a finished product or as a format or script . The scout assesses the potential value of the universals of the product and determines the cultural discount to promote either the finished product or only the format sale. Much like the film optioner, who buys the rights to adapt books for films, the scout surveys potential products from wherever they may stem. The greatest asset of the travelling expert is a keen eye for appealing cultural universals, a very open cultural sensitivity, and a working knowledge, at least, of foreign languages.

The second type of transductor is the merchant. As presented by Bielby (2011) and Kuipers (2012), the merchant carries out his or her work at the audiovisual trade fairs. As opposed to the scout who travels the globe and browses constantly foreign television markets, the merchant usually remains anchored at the headquarters of the production company, travelling exclusively to the trade fairs, where she or he engages in direct trade, both as seller of the company's products, and as potential buyer of other programs. The merchant has a great knowledge of the market balances and prices, and some idea of how to measure potential returns from products with a low cultural discount.

The third concept to describe a transductor is the alchemist. Whereas the scout looks for new things, usually beyond the main markets, and the merchant engages in the more mainstream debates within audiovisual trade fairs, the alchemist is the one who transforms the audiovisual product into the local market. The alchemist removes the cultural lacunae of the product and carries out the reculturalization process. As scriptwriter, translator, dubbing supervisor, show runner (Davis & Nadler, 2010), casting director and/or project director, the alchemist must have acute insight of his or her own culture in order to be able to make a foreign narrative, culturally different, a pleasing and understandable product for the local audiences. Conway's (2012) and Waisbord and Jalfin's (2009) description of gatekeeping seem to fit clearly into this category. As opposed to the cultural openness of the scout, or the market-oriented know-how of the merchant, the alchemist is a keeper of culturally bound knowledge.

Although a cultural transductor may, at once, be scout, merchant, and alchemist, it seems clear that there are different skills required for each of those cultural mediations. By clarifying the roles described, it becomes easier to engage in research about cultural transduction.

The cultural space of transduction: Hybridity and Convergence

People do not work in vacuum. Their process of transduction occurs in certain specific settings which determine the source of their input and the audience of their output. To understand those spaces where transduction takes place, two concepts are debated here: hybridity and convergence.

The concept of Hybridity comes from a postcolonial discourse (Kraidy, 2010) in which the constant influx and exchange of cultural products is taken as a process of mixing, adapting, modifying and accommodating different cultural praxis and texts (García Canclini, 2000). Although the mechanics of hybridity remain under the power distribution of the markets and thus tend to lead towards a homogenization of cultural creation (Roveda Hoyos, 2008), the process of hybridity is evidence of the markedness of global exchanges. Another catchword currently used to describe this cultural transaction is convergence. Although it seems to describe a particular participatory form of engagement fostered by media technologies which enable quick response, international contact and easier content transfer (Deuze, 2006, 2010), it can be traced back to previous forms of private and participatory transformation in print and video (Jenkins, 1992, 2006). Thus, convergence is not a new issue, but rather an old issue which has become more evident in recent times (Arango-Forero, Roncallo-Dow, & Uribe-Jongbloed, forthcoming).

In general terms, the two concepts seem to be similar. Hybridity and convergence have been presented as two faces of the same coin, because they are both processes of appropriation and modification of content (Uribe-Jongbloed, 2013). But since the two different words already exist in academic parlance, it seems suitable to clarify them further.

Uribe-Jongbloed (2013) separates the two concepts by giving a specific meaning to each of the spaces of transduction. He argues that whereas hybridity implies some form of cultural appropriation alongside previously established cultural institutions, -cultural industries, even-, convergence seems to imply a participatory grassroots development fostered and supported by social media networks. This separation he creates is arbitrary, since in the discussions of both hybridity and convergence there is never a distinct division of the terms. Although this difference may not be so easily pointed out in material cultural products, - handcrafts, for example -, it seems easier to determine in audiovisual products, which require a technical system to be made available. However, this separation proves useful to define the setting under which the different actors engage, and the place where cultural transductors, in their various roles, can be defined.

Conclusion: New framework for the study of cultural transduction

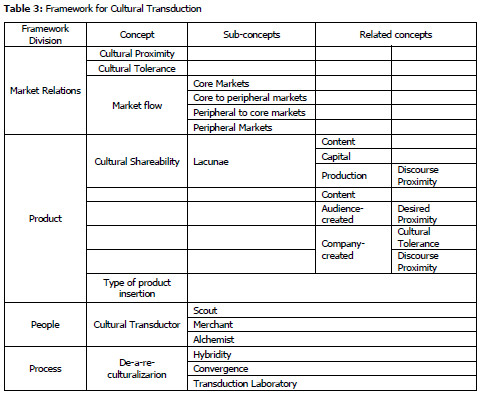

Our final point in this conceptual jigsaw puzzle is to reorganize the existent vocabulary, limit its scope and provide new concepts to strengthen it. This framework (see Table 3) would serve as the basis for international and cross-cultural comparisons of cultural transduction. Notice, however, that this framework can only be used in comparisons, and never as a standalone observation of a market or product.

The framework is divided into four areas of study: Market, Product, People and Process.

Market

First of all, the compared markets are set in one of the four market flows described earlier, in a relation from the core to the periphery, or to those instances within themselves. Furthermore, markets can be defined according to the cultural elements which they share with other markets (religion, language, common history, trade agreements, political institutions), what we consider to be cultural proximity. The more similar those characteristics, the more proximate the two markets are. However, cultural proximity is not enough. Hence, we propose a new element to be studied: cultural tolerance. We define this market characteristic to be the openness or hurdles to products from other cultural markets, whether they tend to be capped by tariffs, taxes, specific language adaptations or quotas, as were many films from Hollywood in various parts of the world (Marvasti & Canterbery, 2005), or other less-evident barriers, such as the US market preference for adaptation or versioning instead of the broadcast of the original, despite language commonalities (see Davis & Nadler, 2010 for the case of an international coproduction).

Product

The type of product exchange is first classified according to the terminology provided in Table 2, defining the type of product insertion which is taking place, notice this only applies to the traded or modified products rather than those with foreign commission or financing. To determine both shareability and cultural discount, we set Rohn's (2010, 2011) model of cultural universals and lacunae.

People

As described earlier, the people involved can be classified, and their tasks framed, by the three roles presented for cultural transductors: scout, merchant and alchemist. Although some people might share various roles, or move easily from one to another, they can be considered separately, regarding the decision-making process at each stage, and their overt or subtle ability to spot and/or modify lacunae, while keeping the universals intact.

Process

Finally, we have the markers of the process. The transduction includes the three stages of de-, a-, and reculturalization, which take place in one of two possible loci, either hybridity or convergence. Hybridity takes place in established cultural audiovisual institutions, whereas convergence happens in the dynamic activities of engaged social networking and participation. One last point regarding the process is the stages or types of audiovisual content modification or alteration involved, and the actual places where those processes take place (within the producer's headquarters, within the buyer's headquarters, somewhere in intermediaries of the production, at specific places devoted to a given cultural adaptation). This final concept would be the transduction laboratory.

References

Agost, R. (2004). Translation in bilingual contexts: Different norms in dubbing translation. In P. Orero (Ed.), Topics in Audiovisual Translation (pp. 63–82). Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Alia, V. (2010). The New Media Nation: Indigenous Peoples and Global Communications. Anthropology of Media. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books. [ Links ]

Appadurai, A. (1990). Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy. In M. Featherstone (Ed.), Global Culture: Nationalism, Globalization and Modernity. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Bielby, D. D. (2011). Staking Claims: Conveying Transnational Cultural Value in a Creative Industry. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(5), 525–540. doi:10.1177/0002764211398077 [ Links ]

Browne, D. R., & Uribe-Jongbloed, E. (2013). Ethnic/Linguistic Minority Media: What their History reveals, How Scholars have studied Them, and What We might ask next. In E. H. G. Jones & E. Uribe-Jongbloed (Eds.), Social Media and Minority Languages: Convergence and the Creative Industries (pp. 1–28). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Bruner, C. M. (2008). Culture, sovereignty, and Hollywood: UNESCO and the future of trade in cultural products. International Law and Politics, 40, 351–436. [ Links ]

Burch, E. (2002). Media literacy, cultural proximity and TV aesthetics: why Indian soap operas work in Nepal and the Hindu diaspora. Media, Culture & Society, 24(4), 571–579. doi:10.1177/016344370202400408 [ Links ]

Castelló, E. (2010). Dramatizing proximity: Cultural and social discourses in soap operas from production to reception. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 13(2), 207–223. doi:10.1177/1367549409352274 [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2009). Communication Power. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Chalaby, J. K. (2012). At the origin of a global industry: The TV format trade as an Anglo-American invention. Media, Culture & Society, 34(1), 36–52. doi:10.1177/0163443711427198 [ Links ]

Conway, K. (2012). Cultural translation, global television studies, and the circulation of telenovelas in the United States. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 15(6), 583–598. doi:10.1177/1367877911422291 [ Links ]

Davis, C. H., & Nadler, J. (2010). International Television Co - productions and the Cultural Discount?: the Case of Family Biz , a Comedy. In 9th World Media Management and Economics Conference. Bogotá. Retrieved from http://www.ryerson.ca/~c5davis/publications/Nadler-Davis-InternationalTelevisionCoproductionv7-12May2010.pdf [ Links ]

De Sola Pool, I. (1977). The Changing Flow of Television. Journal of Communication, 27(2), 139–149. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1977.tb01839.x [ Links ]

Deuze, M. (2006). Ethnic Media, Community Media and Participatory Culture. Journalism, 7(3), 262–280. doi:10.1177/1464884906065512 [ Links ]

Deuze, M. (2010). Convergence Culture in the Creative Industries. In D. K. Thussu (Ed.), International Communication: A Reader (pp. 452–467). London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Eriksen, T. H. (2007). Globalization. Oxford & New York: Berg. [ Links ]

Fiske, J. (2001). Television Culture: popular pleasures and politics. London: Taylor & Francis e-Library. [ Links ]

Fu, W. W., & Govindaraju, A. (2010). Explaining Global Box-Office Tastes in Hollywood Films: Homogenization of National Audiences Movie Selections. Communication Research, 37(2), 215–238. doi:10.1177/0093650209356396 [ Links ]

García Canclini, N. (2000). Culturas Híbridas: Estrategias para Entrar y Salir de la Modernidad. Bogotá D.C.: Grijalbo.

Ginsburg, F. (2008). Rethinking the Digital Age. In P. Wilson & M. Stewart (Eds.), Global Indigenous Media: Cultures, Poetics, and Politics (pp. 287–305). Durham & London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Haynes, J. (2012). Editorial. Reflections on Nollywood?: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of African Cinemas, 4(1), 3–7. doi:10.1386/jac.4.1.3 [ Links ]

Hoskins, C., McFadyen, S., & Finn, A. (1994). The Environment in which Cultural Industries Operate and Some Implications. Canadian Journal of Communication, 19(3), 1–14. Retrieved from http://www.cjc-online.ca/index.php/journal/article/view/824/730 [ Links ]

Hoskins, C., & Mirus, R. (1988). Reasons for the US Dominance of the International Trade in Television Programmes. Media, Culture & Society, 10(4), 499–504. doi:10.1177/016344388010004006 [ Links ]

Hourigan, N. (2004). Escaping the Global Village: Media, Language and Protest (p. x, 205 p.). Lanham, Md. & Oxford: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

Inda, J. X., & Rosaldo, R. (2008). Tracking Global Flows. In J. X. Inda & R. Rosaldo (Eds.), The Anthropology of Globalization (pp. 3–46). Malden et al.: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Iwabuchi, K. (2000). To Globalize, Regionalize, or Localize Us, That Is the Question: Japans Response to Media Globalization. In Gorgette Wang, J. Servaes, & A. Goonasekera (Eds.), The New Communication Landscape: Demystifying Media Globalization (pp. 142–59). London, New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Iwabuchi, K. (2002). Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Iwabuchi, K. (2010). Taking Japanization Seriously: Cultural Globalization Reconsidered. In D. K. Thussu (Ed.), International Communication: A Reader (pp. 410–433). Oxon & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (1992). Textual poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture. Studies in culture and communication (p. viii,343p). London; New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York?; London: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Kraidy, M. M. (2010). Hybridity in Cultural Globalization. In D. K. Thussu (Ed.), International Communication: A Reader (pp. 434–451). London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kuipers, G. (2012). The cosmopolitan tribe of television buyers: Professional ethos, personal taste and cosmopolitan capital in transnational cultural mediation. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 15(5), 581–603. doi:10.1177/1367549412445760 [ Links ]

La Pastina, A. C., & Straubhaar, J. D. (2005). Multiple Proximities between Television Genres and Audiences: The Schism between Telenovelas Global Distribution and Local Consumption. International Communication Gazette, 67(3), 271–288. doi:10.1177/0016549205052231 [ Links ]

Lee, F. L. F. (2006). Cultural Discount and Cross-Culture Predictability: Examining the Box Office Performance of American Movies in Hong Kong. Journal of Media Economics, 19(4), 259–278. doi:10.1207/s15327736me1904_3 [ Links ]

López-Pumarejo, T. (2007). Telenovelas and the Israeli television market. Television & New Media, 8(3), 197–212. doi:10.1177/1527476407302657 [ Links ]

Martin-Barbero, J. (1993). Communication, Culture and Hegemony: From the Media to Mediations. London & Newbury Park: Sage. [ Links ]

Martínez, I. (2005). Romancing the Globe. Foreign Policy, (151), 48–56. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/30048214 [ Links ]

Marvasti, A., & Canterbery, E. R. (2005). Cultural and Other Barriers to Motion Pictures Trade. Economic Inquiry, 43(1), 39–54. doi:10.1093/ei/cbi004 [ Links ]

Moran, A. (2009a). When TV formats are translated. In A. Moran (Ed.), TV Formats Worldwide. Localizing Global Programs (pp. 39–54). Bristol & Chicago: Intellect. [ Links ]

Moran, A. (2009b). New Flows in Global Tv. Bristol and Chicago: Intellect. [ Links ]

Rantanen, T. (2005). The Media and Globalization (p. viii, 180 p.). London & Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE.

Read, W. H. (1976). Americas mass media merchants. Johns Hopkins University Press. Retrieved from http://books.google.com.co/books?id=y_1oAAAAIAAJ [ Links ]

Rivera-Betancourt, J., & Uribe-Jongbloed, E. (n.d.). Cultural Discount and Audiovisual Market Contra-flows in Television Adaptations: The transformation of Yo Soy Betty, La Fea into Ugly Betty. Palabra Clave. [ Links ]

Robertson, R. (1992). Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture. Theory, culture and society (pp. x, 211p). London: SAGE. [ Links ]

Rohn, U. (2004). Media Companies and Their Strategies in Foreign Television Markets. Köln: nstituts für Rundfunkökonomie an der Universität zu Köln. Retrieved from http://www.rundfunk-institut.uni-koeln.de [ Links ]

Rohn, U. (2010). Cultural barriers to the success of foreign media content: Western media in China, India and Japan. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Verlag. [ Links ]

Rohn, U. (2011). Lacuna or Universal? Introducing a new model for understanding crosscultural audience demand. Media Culture Society, 33(4), 631–641. doi:10.1177/0163443711399223 [ Links ]

Roveda Hoyos, A. (2008). Identidades Locales, Lenguajes y Medios de Comunicación: Entre Búsquedas, Lógicas y Tensiones. Signo y Pensamiento, 53(1), 61–69. [ Links ]

Salazar, J. F., & Cordova, A. (2008). Imperfect Media and the Politics of Indulgence Video in Latin America. In P. Wilson & M. Stewart (Eds.), Global Indigenous Media: Culture, Poetics and Politics (pp. 39–57). Durham and London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Salgueiro, R. (2004). Televisión/Europa del Este en romance con la Telenovela Latinoamericana. Revista Latinoamericana de Comunicación CHASQUI, (087), 66–71. [ Links ]

Sánchez-Tabernero, A. (2006). Issues in Media Globalization. In A. B. Albarran, S. M. Chan-Olmsted, & M. O. Wirth (Eds.), Handbook of Media Management and Economics (pp. 463–491). Mahwah, N.J. & London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Singhal, A., & Svenkerud, P. J. (1994). Pro-socially shareable entertainment television programmes: A programming alternative in developing countries? The Journal of development communication, 5(2), 17–30. [ Links ]

Singhal, A., & Udornpim, K. (1997). Cultural Shareability, Archetypes and Television Soaps. Gazette, 59(3), 171–188. [ Links ]

Sparks, C. (2007). Globalization, Development and the Mass Media (p. 258p.). Los Angeles & London: SAGE. [ Links ]

Straubhaar, J. D. (1991). Beyond Media Imperialism: Asymmetrical Interdependence and Cultural Proximity.pdf. Critical Studies in Mass Comunication, 8(1), 39–59. [ Links ]

Straubhaar, J. D. (2000). Culture, Language and Social Class in the Globalization of Television. In Georgette Wang, J. Servaes, & A. Goonasekera (Eds.), The New Communications Landscape: Demystifying Media Globalization (pp. 199–224). London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Straubhaar, J. D. (2007). World television: from global to local. London, Los Angeles, New Delhi and Singapore: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Straubhaar, J. D. (2010). Chindia in the context of emerging cultural and media powers. Global Media and Communication, 6(3), 253–262. doi:10.1177/1742766510384962 [ Links ]

Thussu, D. K. (2010). Mapping Global Media Flow and Contra-Flow. In D. K. Thussu (Ed.), International Communication: A Reader (pp. 221–238). Oxon & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Tunstall, J. (2010). Anglo-American, Global, and Euro-American Media versus Media Nationalism. In D. K. Thussu (Ed.), International Communication: A Reader (pp. 239–244). Oxon & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2005). International Flows of Selected Cultural Goods and Services, 1994-2003 Defining and capturing the flows of global cultural trade. Montreal: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Uribe-Jongbloed, E. (2013). Minority Language Media Studies and Communication for Social Change: Dialogue between Europe and Latin America. In E. H. G. Jones & E. Uribe-Jongbloed (Eds.), Social Media and Minority Languages: Convergence and the Creative Industries (pp. 31–46). Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Waisbord, S. (2004). McTV: Understanding the Global Popularity of Television Formats. Television & New Media, 5(4), 359–383. doi:10.1177/1527476404268922 [ Links ]

Waisbord, S., & Jalfin, S. (2009). Imagining the national: Gatekeepers and the adaptation of global franchises in Argentina. In A. Moran (Ed.), TV Formats Worldwide. Localizing Global Programs (pp. 55–74). Bristol & Chicago. [ Links ]

Wang, Georgette, & Yeh, E. Y. (2005). Globalization and hybridization in cultural products: The cases of Mulan and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 8(2), 175–193. doi:10.1177/1367877905052416 [ Links ]

Webster, F. (2006). Theories of the Information Society (3rd ed.). London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

NOTAS

1 Viacom, Inc.; The Walt Disney Company (Disney/ABC); Sony Corporation; News Corporation; General Electric Company (NBC Universal, Inc.); and, Time Warner, Inc.