Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.8 no.1 Lisboa jan. 2014

Service Quality of News Channels: A Modified SERVQUAL Analysis

Muhammad Mursaleen*, Mubashir Ijaz**, Muhammad Kashif***

*GIFT University, Pakistan

** GIFT University, Pakistan

*** GIFT University, Pakistan

ABSTRACT

Current study investigates the service quality offered by Pakistani news channels through employing a modified SERVQUAL scale. Further to this, the SERVQUAL and its applicability to measure the service quality of news channels has been presented. A 29-item SERVQUAL based instrument was administered to a sample of 318 randomly selected respondents. The descriptive analysis revealed a gap analysis model to infer meaningful results. The results reveal several gaps between expected and perceived service quality. In particular, Responsiveness and Assurance dimensions had the highest gaps. However, the SERVQUAL scale has been a good fit while measuring the service quality of news channels in a developing country context. This research originally contributes to the existing service quality literature as the SERVQUAL scale has never been used to measure service quality of TV channels. The recommendations will be helpful in minimizing the service quality gaps and also can trigger channel loyalty by offering services in accordance with the viewer expectations.

Keywords:Marketing, Service Quality, Media, News channels, Public, expectations, Perceptions, Pakistan.

Introduction

The growth in service sector has been observed across the globe (Rashmi, 2005). This exponential growth in the service sectors has made it difficult for firms to consistently create, share, and sustain memorable customer service experiences (Oakton, 2011). Customers are becoming knowledgeable and selective in terms of buying and consuming services (Juan et al., 2012). Today the service-oriented products are acknowledged as experiences where everyone in a service system has to create and share value for the customers (Vargo and Lusch, 2004). This view recognizes the significant role of customer feedback in order to improve the quality of services offered. The service providers must have a clear understanding of perceived as well as expected quality of service offered so to create and deliver value for the customers (Nazimet al., 2011). The customer satisfaction in service products is usually derived from a combination of technical quality as well as functional quality. However, functional quality is considered important as most customers do not have expertise to evaluate the technical quality (Nandan, and Geetika, 2010). When customers are satisfied with the service quality, they tend to be loyal with the service organization (Siddiqi, 2011). Loyal customers become the referents in order to attract more customers (Mersha et al., 2012). Hence, achievement of service quality is regarded as a critical success factor for service organizations. Despite a handful of research to unearth service quality, the quest for excellence in service delivery is continued and researchers recommend further studies that highlight different cultural contexts (Frimpong and Wilson, 2013).

Watching the Television is a common phenomenon all across the globe. People living in Europe, on average, spend 226 minutes watching the TV in a day, while in U.S it is 297 minutes per day (IP Germany, 2005). In many other countries, people spend most of the time in watching television and it is also evident that in some countries working time and TV watching time is spent equal (Christine and Bruno et al., 2010). Especially after the introduction of cable TV operators, television viewership has been increased exponentially with viewers having more choices and freedom to switch the channel more frequently (Christine et al., 2010). The freedom of choice amongst the broadcasted TV channels and an increase in TV watching hours signals viewers enjoyment with this activity. A large number of people in Pakistan watch TV daily, living in urban and the rural areas. TV viewership has been increased significantly in Pakistan with 63 million viewers in the year 2004 to 86 million in the year 2009 (Gallup, 2010). Eighty five private channels have been working in Pakistan and continuous growth of subscribers is expected in coming years (PEMRA annual report 2010). Pakistani children aged between 4-17 years, Men and Women aged 18 and above, have same television watching habits (Gallup 2012). Due to socio-political unrest, most of the TV channels lie under the category of news channels where news related to current affairs are shared with general public. Interestingly, almost 95 percent of audience likes to watch news channels in Pakistan (Gallup, 2010).

Television viewing has multiple effects on individual consumers as well as on society. All the age groups especially the children are highly influenced by watching TV, even in developing countries (Kashif et al., 2012). TV viewing has been criticized over the years due to; creating unrealistic expectations about marriage (Segrin and Nabi, 2002); affecting food disorders amongst children through advertising targeted at younger children (McGinnis et al., 2006); and promotion of a material culture where human values are almost ignored (Burroughs et al., 2002). However, on the other side, TV viewership is encouraged due to its significant advantage in De-marketing obesity amongst younger population (Wansink and Huckabee, 2005). Watching a TV has also been beneficial in consumer education especially for children about various products and services, ultimately making them more informed and knowledgeable consumers (Mehta et al., 2010). TV viewing has been found to affect social perceptions, beliefs, and self-perceptions (Eisend and Moller, 2007). It solely depends upon the quality of programs broadcasted in order to influence the general public.

Given this exponential growth in TV viewership, its significant impact on people from all walks of life, and the need to broadcast the programs which promote individual and societal well-being by channel owners, there is lack of evidence on the extent of service quality offered by TV channels. The studies pertaining to service quality of TV channels in developed as well as developing world are absent. This is where current study contributes significantly to the literature. It is true that service quality has some features which are universal in nature (Sangeetha & Mahalingam, 2011) however, customer expectations and perceptions are cultural phenomenon (Bick et al., 2010). Therefore, this article seeks to present service quality delivered by media channels in Pakistan. The gaps model has been employed to measure the extent of service quality (difference between expected and perceived quality) delivered by these channels. Pakistani media channels have been under scrutiny by the media experts who criticize these channels of not reflecting a family-oriented culture (Tribune, 2012). The trend of obesity and overweight issues among Pakistani children has also been attributed to TV viewing (Mushtaq et al., 2011). These issues necessitate a study which can help news TV news channel owners and media managers to provide with current state of public satisfaction and some useful marketing strategies to minimize the dangers to society. There are five perspectives to delineate the quality of TV channels namely; producer view, manager view, curator view, regulator view, and consumer view (Murroni and Irvine, 1997). However, to strengthen the methodology and achieving highly focused results, the researchers only took into consideration the consumer view to aim in answering the following research questions;

RQ1: What are the expectations of TV viewers about TV channels?

RQ2: What is the extent to which public is satisfied with the service quality offered by various TV channels?

This article has been presented through explaining the recent literature on service quality, mixed methods employed to collect and analyze the data, findings from the study, and conclusion section where service marketing theory with respect to TV channels has been discussed.

Literature review

Service quality

Service quality has been regarded as a key issue facing the service organizations since last 20 years (Ladhari, 2009). Service quality in services positively contributes in developing public trust on the service organization (Cronin and Taylo, 1992). Customers are not passive today, rather more knowledgeable and empowered to direct the service organizations (Donnelly et al., 1995). In order to measure the service quality, an understanding of customer expectations is pivotal (Parasuraman et al., 2004). Based on certain expectancy theories, expectations are defined as partial beliefs about a product that serve as standards or reference points against which a product is judged (Ziethaml and Berry, 1993). It can be stated that customer expectations are the standards which must be met in order to ensure service quality. With these expectations in mind, quality has been attributed as difference between expected quality and perceived quality (Parasuraman et al., 1985). It is however pivotal to measure both; the expectations as well as perceptions so that an analysis of service quality can be made (Parasuraman et al., 1985, Parasuraman et al., 1988). The gaps between expectations (E) and perceptions (P) are measured which help researchers to reach at meaningful conclusions about current state of service quality. It has been observed that service quality researchers always come up with some gaps which are understandable because customers have higher expectations (Friman and Fellesson, 2009).

There are several differences between goods and services which demand customized marketing approaches to be employed for service firms. An understanding of these differences will enable the service marketers to achieve success in the long-run. Services are intangible, where measuring the service quality is really a challenging task. As a service provider, intangibility also complicates the process of inventory management where no prior stock can be retained (Mersha et al., 2012). Customers and employees interact in various service encounters where employees need to have people management skills (Chase, 1978). It is also believed that the physical facilities of service provider must be clean and aesthetically appealing which can influence the satisfaction levels of customers (Carlzon, 1987). Hence, customer satisfaction is more challenging in services as compared with goods. On the other side, satisfying customers in service setting is imperative and leads to customer loyalty (Siddiqi, 2011). In various service settings, customers have some standards, also known as customer expectations which form the basis for evaluating the quality of any service. The expectations may or may not meet the customer standards which can lead to several gaps in managing services (Parasuraman et al., 1985).

The SERVQUAL scale

The initial model of SERVQUAL was presented as Gaps Model by Parasuraman et al. (1985). Researchers outlined the differences between customer expectations and perceptions. Higher gaps between expectations and perceptions were regarded as low service quality and vice versa (Parasuraman et al., 1988). SERVQUAL is a customer satisfaction tool which incorporates some pre-service customer expectations and compares these with post-service performances to determine the extent of customer satisfaction (Parasuraman et al., 1994). Customers are considered as satisfied once their expectations are met. Over the years, SERVQUAL instrument has been widely used as a measure to evaluate the customer satisfaction in services sector. The SERVQUAL instrument has five dimensions; tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy (Ham et al., 2003). The service expectations are the must have criteria in order to satisfy customers where a firm needs to minimize the following gaps (Riadh, 2009);

- Customer Gap: The difference between customer expectations and management perception of customers expectations.

- Service Standard Gap: The difference between management perceptions of customer expectations and translation of these expectations into service standards.

- Service Performance Gap: The difference between actual service delivery by frontline in a high contact service and the specifications perceived by management.

- Service Delivery Gap: The difference between promises made through different marketing communications and actual service delivery.

- Service Quality Gap: The difference between customer expectations of service quality and customer perceptions of service quality.

The SERVQUAL is a generic instrument which is used to measure service quality in different industries including Healthcare, Banking, Fast food, Telecommunication, Retail chain, Information system, Library services across the globe (Riadh, 2009).The identification of these gaps through SERVQUAL portrays the actual performances of a firm and helps the managers to minimize the identified gaps through taking remedial measures (Mohsin and Ernest, 2010). Despite its usefulness, the SERVQUAL has been criticized for its operational and conceptual limitations which question the application of the scale across the globe (Jabnoun and Khalifa, 2005; Landrum et al., 2007). Some others question its psychometric properties and hold the opinion that all five dimensions of SERVQUAL are not generically applicable to all service contexts (Arasli et al., 2005; Badri et al., 2005). The researchers recommend using SERVQUAL scale by grounding the five dimensions of SERVQUAL in the context of investigation (Ladhari, 2008). These adaptations will help the marketers to understand the cultural definitions of customer expectations, leading to formulation of highly customized marketing strategies to improve the service performances (Barabino et al., 2012). These researchers have successfully encountered the challenges of operationalizing SERVQUAL in different country contexts to offer useful strategies in order to improve performance.

In order to increase the operational efficiency of a scale, its understanding is pivotal for marketers. The five dimensions of SERVQUAL are described below:

- Tangibles: The extent of physical facilities, tools and equipment used such as signboards, furniture etc.

- Reliability: The consistency of delivering error-free service, over a period of time.

- Responsiveness: The employees eagerness to deliver service such as their body language.

- Assurance: The extent of knowledge and courtesy employees possesses.

- Empathy: The skills to pay individualized attention to every customer.

Due to intangible nature of services, many researchers limit themselves to measure only the perceived quality by discarding expected quality (Mohsin and Ernest, 2010). Although many tools are available to measure service quality but the issue of SERVQUAL as a tool to measure service quality has remained a critical decision for researchers. Some believe that SERVPERF is a good choice when compared with SERVQUAL, in terms of the scope (Francois and Fernando, 2007). Francois and Fernando (2007) conducted a meta- analytic study based on 17 years of research published on the application and challenges of SERVQUAL. The results of their study confirmed the application of both scales: SERVQUL and SERVPERF. However, it was also found that due to better diagnostic nature of SERVQUAL scale (perceived and expected both qualities), it attracted more scholastic interest than any other scale used so far to measure service quality.

Problem statement

Every organization seeks to gain a handful of profit which can be earned through offering different products and services. TV networks gain profit by offering different type of programs however; the high cost of airtime is real challenge to stay profitable (Chorianopoulos and Spinellis, 2005). Viewers like to watch the programs of their choice and many a times are difficult to retain (Wilbur, 2008a). In order to attract viewers, channels use several strategies which cause hypertension and other disease spread among viewers (Pardee et al., 2007). The tactics used by several news channels induce the feeling of fear, anger and disgust among the viewers (Newhagen, 1998). However, the channels are not to be criticized as their task is to present the actual state of socio-political environment in a country (Aalberg et al. 2010). Whether the situation is good or bad, the primary task of media channels is to communicate the message to public. However, to develop public trust on the news, channels must be credible, liked by the viewers, representative of local culture, and have a reputation of quality (Sunder et al., 1999). Juan et al. (2012) while investigating the program choice found that program variety on TV channels increase the satisfaction of viewers. Further to this, they found that customer satisfaction depends upon different factors such as; creativity of programs, cast of models, and visual appeal. High frequency of TV commercials has also resulted into an increasing trend to switch the channels as many viewers avoid watching commercials (Elpers et al., 2003). The interest developed by program is another significant dimension which signals high quality and results in public trust on TV channels (Tse and Lee, 2001). Higher interest developed by TV channels signal reliability of the service performed. However, there are some personal, situational, and media-related variables identified which cause consumer channels switching (Steve and Ian, 2010). Media studies investigating channels switching, building public trust and overall quality of TV channels have so far explicated the advertising avoiding behavior as a remedial measure (Elpers et al., 2003; Dix and Phau, 2010). No prior study investigates the service quality offered by media channels which can help the authorities to understand public expectations and the quality delivered. Current study is planned to fill this knowledge gap. The results will help media managers, especially in news channels to customize the theme of news, broadcasted to communicate with general public.

Research objectives

- To understand the public expectations regarding TV news channels

- To demonstrate the differences between perceived and expected quality offered by TV news channels

- To demonstrate the extent of SERVQUAL model fitness measuring service quality of news channels

- To offer useful and practical marketing strategies in order to bridge the service quality gaps between expectations and perceptions.

Methods & precincts

The SERVQUAL scale has been used as a culturally-sensitive scale by many service marketing researchers. It is evident that SERVQUAL has been modified as per the context of investigation (Barabino et al., 2012; Ramseook-Munhurrun et al., 2009). The initially developed scale by Parasuraman et al. (1991) was taken into consideration for this study and was modified to fit-in with media service quality research settings. Every item of the scale was re-worded to suit the service setting. For example, under the Reliability item: The employees deliver error-free services was replaced by Media is sharing truthful information. This was done under the guidance of several senior professors whom are well versed with the research techniques and methods. The instrument consisted of two major parts; expectation (E) items and perceived (P) quality items. Although a 7-point Likert scale has been used in SERVQUAL studies but most of the researchers have extensively used a 5-item scale (Ramseook-Munhurrun et al., 2009). Hence, for this study, the scale ranged from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly Agree. The use of a 5-point Likert scale has been advocated by early researchers in the field of services marketing (Babakus and Mangold, 1992). An initial 29-item scale was pilot tested with 10 respondents and the respondents ease and understanding with the scale was observed. The pilot testing procedure and number of respondents to use for pilot study was guided and opted from SERVQUAL studies (Ramseook-Munhurrun et al., 2009). After performing a pilot test, it was observed that there is no need to reduce the number of items from the instrument which was finalized as a 29-item scale.

The scale was administered by research team personally in the vicinity of Gujranwala city, located in the province of Punjab, Pakistan. The data collection took one month from December, 2012 to January, 2013. A total of 350 people were approached for the purpose of this study, to which questionnaire was personally distributed. The sample size calculation has been guided through the recommendations made by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994). These researchers suggest a sample size of 300> in order to attain some reliable results and analysis in psychometric measurements. There were 29-items in the modified SERVQUAL scale and with the proportion of 10:1, a sample size of 300 and above would have been appropriate. Amongst the 350 questionnaires distributed for the purpose of data collection, research team was able to collect back 318 responses which were considered valid for this study. Given the suggestions of researchers regarding sample size, 318 is an acceptable number of respondents to ensure reliability of results. The data collected was analyzed through SPSS 16.0 and various reliability tests and descriptive analysis were performed to unleash the gaps which exist between expectations and perceptions of TV viewers.

Results

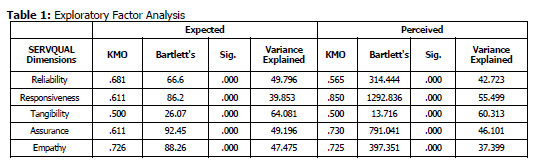

Technically, to assess the psychometric properties of modified SERVQUAL scale, the principle component factor analysis with Varimax was used. It was decided that the items with an eigenvalues of above 1.0 and the loadings equal to or greater than 0.50 will be retained (Hair et al., 1998). The variance explained for expected and perceived service quality has been discussed through Table 1.

Kaiser Meyer Olkin (KMO) and Bartletts are the two assumptions of Exploratory Factor analysis (EFA). These assumptions need to be fulfilled before moving ahead with further statistical analysis. These results of present the sample adequacy and other reliability measures for instrument designed. The Value of KMO, as suggested by researchers must be greater or equal ant to 0.6 while the value of Bartletts must be significant at less than 0.05. The results of this study, based on these two tests reveal that basic assumptions of exploratory factor analysis have been fulfilled. The data is reliable for further analysis and sample is adequate to infer and rely on the results. It is also evident that Tangibility dimension with Variance score of 64.081 explains the variations in customer expectations of service quality offered by news channels in Pakistan. The same is true for Perceived quality offered by news channels.

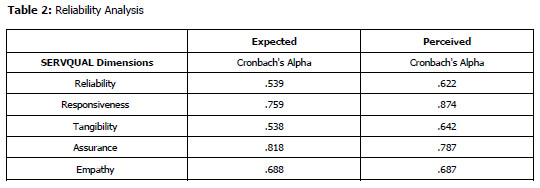

Reliability of data shows that all the dimensions employed to investigate the service quality offered by news channels are reliable. For the reliability, Cronbach Alpha scores must be grater or equal to 0.5 (Nunnally, 1967). The use of Cronbach Alpha in service quality studies has been observed recently (Mohsin and Ernest, 2010). Before moving to data analysis, missing value analysis was also performed to attain highly reliable results.

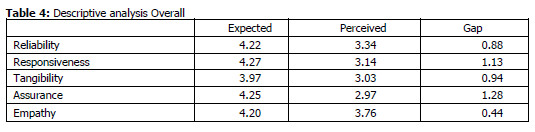

Table 3 presents the mean differences between expected and perceived quality offered by news channels in Pakistan. Table 4 presents the mean scores for the five dimensions of SERVQUAL in terms of the difference between expectations and perceptions. Means score of both expected and perceived service of channels were compared to reach at a gap (E – P=Gap), as proposed by service marketing researchers (Mohsin and Ernest, 2010).

The results reveal that there are gaps in overall quality offered by news channels in Pakistan. Overall the largest gap was found in the difference between expected and perceived quality in terms of Assurance dimension (1.28). The responsiveness has been evidenced as the second highest gap between expected and perceived quality offered by news channels in Pakistan (1.13). It is interesting to note here that Responsiveness has the highest expected value (4.27) which reflects the public reference while watching news channels in Pakistan. Although the public is not satisfied with the overall quality of service offered however; based on the mean results, public perceives news channels are empathic up to a certain extent.

By explaining the five dimensions individually, it can be observed that gaps exist in all the 29 items. This also means that the public is not satisfied with the quality of service offered by news channels in Pakistan. Reliability had five dimensions with the highest gap observed in the item News channels are depicting true picture of politics (E-P=1.60). The Responsiveness item News channels are providing education and useful information with a gap score of 1.56. There are gaps in Assurance dimension as well with the largest gaps found in items News channels are free from corruption (1.79) and News channels are working in line with the Islamic principles (1.82). The largest gap under the Tangibility dimension was found in the item News channels are representative of Pakistani culture (1.51). The largest gap was found in the Empathy dimension in the item Commercials in news channels are few (1.39).

Discussion

There are numerous studies conducted to investigate the service quality of different sectors such as healthcare, banking, and transport services (Mersha et al., 2012; Friman and Fellesson, 2009; Mohsin and Ernest, 2010). However, the research pertaining to the service quality offered by news channels were absolutely missing which formed the basis to conduct this study. Another motivation which fostered the conduct of this study was the frustration of general public observed by the principal author with regards to news media channels. Current study objectively identifies the public expectations from news channels. Based on these expectations, a SERVQUAL approach has been employed to understand the state of service quality offered by news channels in Pakistan. The study is an original and pioneer work in the field of service quality where the context of Pakistani news channels.

Culture of Pakistan is different from western countries mainly in essence that Pakistanis are by large a collectivist society (Hofstede, 2001). Several other differences are visible based on the Hofstede dimensions. These differences make Pakistan an interesting country to investigate with regards to service quality of media channels. Current study presented the gaps found between viewers expectations and their perceptions about service quality offered by news channels. In Pakistan children aged (4-17), women aged 18 plus and men aged 18 plus mostly have same television watching habits. Children spend more time as compare to men and women for watching television in 4pm to 6pm slot (Gallup 2012). Additionally, the whole family is exposed to various TV programs and there is no limit of time as per age of the viewers. Given these statistics, it is alarming that an overall highest gaps is found in the Responsiveness dimension. Due to having a collectivist culture, the family members watch TV in groups. Considering the gaps found in all the dimensions, it can be inferred that the channel loyalty and public trust cannot be attained unless the public is satisfied with the segmentation and content of the news channels (Juan et al., 2012).

The socio-political unrest is observed in all parts of the world including the African, Asian, as well as European countries. We acknowledge that the core task of media is to present the true picture of society in the local socio-cultural contexts (Aalberg et al. 2010). Despite this acknowledgement, public do not perceive that news channels are truthful. This is evident by the results of Reliability and Responsiveness. Again referring back to culture, TV watching in family gatherings is hilarious as public perceives that news channels repeatedly share the breaking news in order to gain better ratings and become consumer choice. It will badly affect the adolescents and children of all ages (Kashif et al., 2012).

Islam is a religion of peace and harmony for the masses. The public in Pakistan perceive that news channels are not reflecting Islamic principles towards life and media freedom is not righteously exercised. These results are in line with the studies conducted to explain the role of media in spreading materialism among the viewers (Burroughs et al., 2002). The largest gaps found under the Assurance dimension are related to public expectations that media must be corruption free and must follow the Islamic principles and tradition. We acknowledge the strong competition amongst the news channels however the media managers must take into consideration that frequency of communication and TV viewing can cause the feelings of anxiety, fear, and frustration among viewers (Newhagen, 1998).

Individualized attention is another important concern among service marketing managers as paying individual attention in services is considered important to succeed (Ladhari, 2009). The Pakistani public does not perceive that news channels are customizing their offers in terms of time, variety of programs/talk shows, and ultimately catering to the needs of individual segments with different psychographics. These expectations are in lie with the results of recent studies conducted in the field of service marketing (Barabino et al., 2012). One must also note that Pakistani score high on Power Distance Index (PDI) which translates them as individuals who acknowledge and demand power (Hofstede, 2001). This power distance index can be linked with the need to receive individual attention among a group of people. Operationally, it seems difficult to attain customer satisfaction based on individual attention to be provided by media channels. However, a highly customized plan is possible with segmentation based on local culture, rituals, and adaptations. Further to this, public expect that there must be minimum TVCs during the talk shows and other informatory programs. Minimizing TV commercials during important programs help researchers to reduce channel switching and channel loyalty (Dix and Phau, 2010).

Role of employees is considered pivotal for the success of service organizations (Nazimet, 2011). Pakistani public expect that the news anchors must be real, and serious while presenting any news depicting crisis situations. This can be linked with public perceptions of service quality based on individual experiences where employees play the key role in building trust and credibility in the media industry (Sundar, 1999). Employees can help service organizations to achieve the customer criteria of credibility and quality of news channels.

Conclusion

The study made meaningful contribution to the existing body of knowledge. Firstly, a modified SERVQUAL has been employed. Secondly, the Asian customers expectations from news channels have been explored for the first time. Thirdly, the context of Pakistan is unique in the sense that no prior studies unearth the service quality offered by news channels in Pakistan. The conduct of this study is very useful for media marketing managers and owners of news channels as the customer expectations have been presented. These managers and other decision makers can take into consideration the public expectations in order to devise marketing strategies which will lead to customer satisfaction and loyalty. In particular, an emphasis should be made on religious perspectives while communicating with the public. The results also reveal that public does not trust much on the credibility and quality of news channels which is alarming sign in an era of high competition. There are gaps found in all the dimensions of SERVQUAL but the largest gaps are observed under responsiveness and assurance dimensions. The researchers are of the view that these two dimensions must be specifically concentrated while devising marketing strategies. The researchers recommend several strategic options for channel marketing managers and other decision makers. Firstly, news channels must spread truthful and timely information to the people so that an element of trust can be established between public and media channels. This can be achieved through strengthening the evidence and its validity before a news or any information is broadcasted. In order to achieve credibility, the product mix must be stretched horizontally or vertically through employing a welfare marketing approach. Welfare marketing strongly stresses the need to identify the public benefit, and then devise a marketing strategy around their needs. In case of media, we propose that media must recognize its role in consumer education where more and more education-centered programs such as documentaries lectures of university staff etc. must be broadcasted. Secondly, Talk shows telecasted on news channels must also focus on addressing the Islamic topics through these shows. Media is acknowledged as a strongest social institution; playing a significant role in developing self-reference criteria of the people. It is a big responsibility which must be achieved through emphasizing culturally-specific and religious Islamic programs. It can be achieved through inviting religious scholars from all sects to appear and share the Islamic thought and culture. It will benefit the whole family in culture such as Pakistan where people watch TV in groups, in larger parts of Pakistan; rural market. Thirdly, the frequency of breaking news must be minimized as it is a major cause of stress and anxiety amongst the viewers. Sharing the similar news again and again loses its true importance and value as in the case of advertising. Hence, the minimization of crisis news will help the media marketers in better able to position their channels as brand, generating favorable loyalty. This can be achieved through employing a market development strategy. There is no need to communicate breaking news during the time when children are watching TV. Hence, it is only possible when the time slots are identified so that the needs of various target groups are well served. This can be achieved through conducting proper market research in Pakistan to identify the time slots various consumers use to watch television. We propose a highly concentrated marketing strategy which will help marketers to identify segments, and then offer highly customize programs according to the needs of segments.

There are several strengths of the methodology opted for this study. Firstly, a context-specific SERVQUAL-item scale has been used to understand the customer expectations of service quality. Secondly, the gaps model has been used by explaining the difference between expected quality and the perceived quality. Thirdly, a significantly large number of respondents have been selected as a sample for this study, based on the recommendations by renowned statistics experts. Despite the significant contextual and methodological contributions, there are several limitations. Firstly, the sample of respondents was selected from a university in the province of Punjab for the purpose of convenience. However, there are many service quality studies noted which consider students as sample respondents. This generally limits the generalizability of research results. Future researchers are strongly recommended to incorporate a more representative sample of respondents to better generalize the results. Secondly, the robust statistical techniques are not used to analyze the data. Although the analysis through mean scores serves the purpose of study, still we recommend future researchers to incorporate the model fitness and application of various other measurement models through structural equation modeling.

References

Aalberg, T., Van Aelst, P., & Curran, J. (2010). Media systems and the political information environment: A cross-national comparison. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 15(3), 255-271. [ Links ]

Afzal and Shehla, 2011, Cultural diversity in Pakistan: national vs provincial. Mediterranean journal of social science vol. 2 pp. 331. [ Links ]

Agirreazaldegi, T. (2008). Audiovisual documentation in the preparation of news for television news programs. Aslib Proceedings, 60(1), 47 – 54. [ Links ]

Anderson, E. W. (1994). Cross-Category Variation in Customer Satisfaction and Retention: Marketing Letters, 5, 19-30.

Artero, J. P., Etayo, C., & Sánchez-Tabernero, A. (2012). Effect of advertising on perceived quality by TV viewers. [ Links ]

Babakus, E. & Mangold, W.G. (1992). Adapting the SERVQUAL scale to hospital services: an empirical investigation. Health Services Research , 26(6), 767-86. [ Links ]

Barabino, B., Deiana, E., & Tilocca, P. (2012). Measuring service quality in urban bus transport: a modified SERVQUAL approach. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 4, 238 – 252. [ Links ]

Barabino, B., Deiana, E., &Tilocca, P. (2012). Measuring service quality in urban bus transport: a modified SERVQUAL approach. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 4(3), 238-252. [ Links ]

Benesch, C., Frey, B. S. & Stutzer, A. (2010). TV Channels, Self-Control and Happiness. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 10(1), Article 86. [ Links ]

Bick, G. G., Abratt, R. R., & Möller, D. D. (2010). Customer Service Expectations in Retail Banking in Africa. South African Journal of Business Management, 41(2), 13-27. [ Links ]

Butt, M. M., & Run, E. C. (2010). Private healthcare quality: applying a SERVQUAL model. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 23(7), 658 – 673. [ Links ]

Carrillat, F. A., Jaramillo F., & Mulki, J. P. (2007). The validity of the SERVQUAL and SERVPERF scales: A meta-analytic view of 17 years of research across five continents. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 18(5), 472 – 490 [ Links ]

Chase, R. B. (1978). Where does the customer fit in a service operation? Harvard Business Review, 566, 137–142. [ Links ]

Cronin Jr, J. J., & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension.The journal of marketing, 56, 55-68. [ Links ]

Dix, S., & Phau, I. (2010). Measuring situational triggers of television channel switching. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 28(2), 137-150. [ Links ]

Dix, S., & Phau, I. (2010). Measuring situational triggers of television channels switching. Marketing intelligence and planning, 285(2), 137-150. [ Links ]

Donnelly, M., Wisniewski, M., Dalrymple, J. F., & Curry, A. C. (1995). Measuring service quality in local government: the SERVQUAL approach.International Journal of Public Sector Management, 8(7), 15-20. [ Links ]

Eisend, M., & Möller, J. (2007). The Influence of TV Viewing on Consumers Body Images and Related Consumption Behavior, Marketing Letters, 18, 101-116. [ Links ]

Friman, M. and Fellesson, M. (2009). Service supply and customer satisfaction in public transportation: the quality paradox. Journal of Public Transportation, 12(4), 57-69. [ Links ]

Gallup Pakistan and Gilani research foundation. (2012). Media and television Audience measurement cyberletter. [ Links ]

Geetika, & Nandan, S. (2010). Determinants of customer satisfaction on service quality: a study of railway platform of India. Journal of public transportation, 12, 97-113. [ Links ]

Gunter, B. (2005). Trust in the news on television. Aslib Proceedings, 57(5), 384-397. [ Links ]

Ham, C.L., Johnson, W., Weinstein, A., Plank, R. & Johnson, P.L. (2003). Gaining competitive advantages: analyzing the gap between expectations and perceptions of service quality. International Journal of Value-Based Management, 16, 197-203. [ Links ]

http://galluppakistan.blogspot.com/2010/05/95-of-all-pakistani-tv-viewers-prefer.html Accessed March 2013.

http://tribune.com.pk/story/418248/tv-channels-spreading-vulgarity-pemra-doing-nothing-chief-justice/ [Accessed on 18 May, 2013].

http://www.gallup.com.pk/News/Media%20Cyberletter%20June%2009%20%282nd%20version%29.pdf Accessed March 2013.

Hussain, N., Bhatti, W. A., & Jilani, A. (2011). An empirical analysis of after sales services and customer satisfaction. Management & marketing challenges for the knowledge society, 6(4), 561-572. [ Links ]

IP Germany 2005. Television (2005): International keyfacts. Cologne, Germany: IP Germany. [ Links ]

Koenig, H. G. (1990). Research on religion and mental health in later life: A review and commentary. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23, 23-53. [ Links ]

Ladhari, R. (2009). A review of twenty years of SERVQUAL research. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 1(2), 172 – 198. [ Links ]

Ladhari, R. (2009). A review of twenty years of SERVQUAL research. International Journal ofQuality and Service Sciences, 1, 172-98. [ Links ]

McGinnis, J. M., Gootman, J. A., &Kraak, V. I. (2006). Food marketing to children and youth: threat or opportunity? Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Mehta, K., Coveney, J., Ward, P., Magarey, A., Spurrier, N., Udell, T. (2010). AustralianChildrens Views about Food Advertising on Television. Appetite, 55, 49-55. [ Links ]

Mersha, T., Sriram, V., Yeshanew, H., &Gebre, Y. (2012). Perceived service quality in Ethiopian retail banks.Thunderbird International Business Review, 544, 551-565. [ Links ]

Mosahad, R., Ramayah, T., & Muhammad, O. (2010). Service quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty: A test of mediation. International business research, 3(4), 72-80. [ Links ]

Moschis, G., Ong F. S., Mathur, A., Yamashita, T., & Benmoyal-Bouzaglo, S. (2011) .Family and television influences on materialism: a cross-cultural life-course approach. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 5(2), 124 – 144. [ Links ]

Murroni, C. and N. Irvine. (1997). The Best Television in the World, in Quality in Broadcasting , C. Murroni et al. Institute for Public Policy Research, London. [ Links ]

Nakamoto Eds., Advances in consumer research. Valdosta, GA: Association for Consumer Research.

Newhagen, J. E. (1998). TV news images that induce anger, fear, and disgust: Effects on approach-avoidance and memory. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 42(2), 265-276. [ Links ]

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory . New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Parasuraman, A., Berry, L.L. & Zeithaml, V.A. (1994). Reassessment of expectations as a comparison standard in service quality measurement: Implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, January, 111-24. [ Links ]

Parasuraman, A., Berry, L.L., & Zeithaml, V.A. (1988). SERVQUAL: a multiple item scale for measuring customer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, Spring, 12-40. [ Links ]

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (2004). Refinement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL scale. Journal of retailing, 67(4), 114. [ Links ]

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Leonard L. (1985). A conceptual model on service quality and its implication for future research. Journa of marketing, 49, 41-50. [ Links ]

Pardee, P. E., Norman, G. J., Lustig, R. H., Preudhomme, D., &Schwimmer, J. B. (2007). Television viewing and hypertension in obese children. American journal of preventive medicine, 33(6), 439-443. [ Links ]

PEMRA annual report 2010.

Ramseook-Munhurrun, P., Naidoo, P., Soolakshna D., & Bhiwajee L. (2009). Employee perceptions of service quality in a call centre. Managing Service Quality, 19, 541 – 557. [ Links ]

Sangeetha, J., & Mahalingam, S. (2011). Service quality models in banking: a review. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 4, 83 – 103. [ Links ]

Segrin, C., & Nabi, R. L. (2002). Does television viewing cultivate unrealistic expectations about marriage? Journal of Communication, 52, 247–263. [ Links ]

Shah, S. A. M., & Amjad, S. (2011). Cultural diversity in Pakistan: national vs provincial. Mediterranean journal of social science, 2, 331-344. [ Links ]

Siddiqi, K. O. (2011). March. Interrelations between service quality attributes, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty in the retail banking sector in Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management, 12–37. [ Links ]

Siddiqi, K. O. (2011, March). Interrelations between service quality attributes, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty in the retail banking sector in Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management, 12–37. [ Links ]

Sundar, S. S. (1999). Exploring receivers' criteria for perception of print and online news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 76(2), 373-386. [ Links ]

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of marketing, 1-17. [ Links ]

Wansink, B., & Huckabee, M. (2005). De-marketing obesity. California Management Review, 47, 6–18. [ Links ]

Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1993). The nature and determinants of customer expectations of service. Journal of the academy of Marketing Science, 21(1), 1-12. [ Links ]