Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Observatorio (OBS*)

On-line version ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.9 no.1 Lisboa Jan. 2015

Virtual identities of Muslim women: A case study of Iranian Facebook users1

Marziyeh Ebrahimi*, Ramón Salaverría**

* PhD Student at the School of Communication, University of Navarra, Campus Universitario 31009 Pamplona, Navarra, Spain. (mebrahimi@alumni.unav.es)

** Associate Professor of Journalism at the School of Communication, University of Navarra, Campus Universitario 31009 Pamplona, Navarra, Spain. (rsalaver@unav.es)

ABSTRACT

The virtual identity of women in the cyberspace surrounding Muslim countries is undergoing a process of differentiation from real-life identity. Although in some Arab countries women present themselves in online social networks as faceless users, in other Muslim countries, such as in Iran, they act differently. Despite the risk of possible real-life consequences, in some Muslim countries women are starting to feel free to decide how to present themselves on the Net, especially regarding the Islamic hijab. In addition, Muslim men and women are engaging in more open dialogue through their digital identities. Furthermore, social networks have given Muslim citizens a political voice, giving them the freedom to express what they object to in social or political terms. Within the context of Iranian society, this research project analyzes how the virtual and real behavior of female Muslim Facebook users varies and how the social networks are pushing them towards a kind of ‘Westernization’. The data has been collected through a content analysis of 550 public Facebook profiles of Iranian female users who live inside and outside this country.

Keywords: Internet, social networks, women, censorship, Muslim countries, Iran

1. Introduction

Whether it be film, television, radio or the Internet, virtually any medium of communication that relies on technology will at one time or another find itself accused of causing a revolution. Just as quickly, one will find some segments of society that oppose the revolution, which is now the case in the evolution of technologies for computer-mediated communication, particularly the development of the Internet. A backlash against these technologies has already begun, and some decry the loss of personality that often accompanies the mediation of communication via computer (Jones, 1997: p. 7). In his 1992 science fiction novel Snow Crash, the author Neal Stephenson first developed the construct of Metaverse. This seminal book depicts a future where individuals inhabit two parallel realities: their everyday physical existence and their avatar existence within a 3D computer-mediated environment. The complicated marriage of everyday mundane life with a fantasy world in which an inhabitant assumes other identities, opened the door to digital social experimentation and offered a pathway to self-aggrandizement for those whose “real world” lives are less than ideal (Solomon & Wood, 2009: p. vii).

The Internet identity of Iranian users has entered on a process of differentiation from how they present themselves in the real world. These differences have broken some long established social norms and taboos. Due to the tradition that governs Muslim society, which limits interpersonal communications, the changes of behavior in virtual worlds are remarkable. Social networks are connecting people in a way that could hardly have been imagined just a few short years ago. Furthermore, the characteristics of the virtual world, which allows users to have temporary, anonymous, changeable, multi-dimensional, computer-based identities, seem to confer on users a kind of freedom that is not marked by a fear for one’s reputation.

At the same time, Facebook has become a space in which Iranians may escape from “governmental culture”. This expression was used by Hassan Rouhani, the current Iranian president, in criticizing the government of Ahmadinejad during the 2013 presidential campaign. The point is that the culture which is ruling (governmentally) over Iran is not Persian public culture, but the government’s culture, which includes the music, movies, theater performances, television, radio, visual arts, etc. that the government officially certifies.

In this paper, the behavior of Iranian Muslim female Facebook users, the most popular social network among Iranians, is analyzed. The research aims to find out how this group of users behaves in cyberspace and how much their virtual identity on the Internet differs from how they behave offline. In addition, their behavior in relation to the governmental culture is also analyzed, in order to see if Facebook has become a space of fighting for Persian public culture and against the governmental culture.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. ‘Social identity’ vs. ‘virtual social identity’

The virtual self refers to “the technology-mediated self, simulated in virtual environments” (Jin, 2008: p. 2160), while, social identity is based on the attributes which derive from the membership of individuals of a social group (or groups), together with the values and emotional significance attached to that group membership (Tajfel, 1978: p. 225).

But what exactly do we mean by the term “identity”? In social psychology, identity is defined as all the answers to the question “who am I?” (Tajfel, 1981) But how do users define themselves on the Internet? Is their identity an avatar, profile picture, About me or CV?

Regarding female Qatari Muslim users’ behavior on the Internet, Rajakumar (2012) has written:

“While American college students are posting compromising photos of parties, relationships or outings - perhaps unthinkable - from their smart phones at all hours of the day and night, female Qatari college students, and indeed Muslim women of all ages in Qatar, often do not use any image at all on their pages, this is not due to the lack of technology or ability, as the population are fairly similar in their degree of middle class affluence and technological savvy. Instead of a photo of herself in a bathing suit or embracing a friend or even just a self portrait, a Qatari female user’s profile is most often that of a younger relative, favorite celebrity or object. Many women in Qatar do not use full names or photos to identify themselves with their Facebook profiles, blogs or Twitter accounts.”

People in virtual communities do just about everything people do in real life, but they leave their bodies behind. You can’t kiss anybody and nobody can punch you in the nose, but a lot can happen within those boundaries.

2.2. Characters of virtual identity

A virtual world is an online representation of real world people, products and brands in a computer mediated environment (Solomon & Wood, 2009). The technology of the Internet provides us with the means to remain anonymous in our communication and the means to break off interaction and observation with the flick of a switch or a click of a mouse. Technology secures our rights as individuals while providing the capability to circulate via mediation, among other things. We transcend self-expression by simultaneously fitting an identity and making it mobile, such as a photograph or image that is transportable or messages sent to groups (Jones, 1997: p. 7).

Users must be considered for at least two reasons: first, they have critical individual differences and they are creative rather than closed; second, people differ in their perception of the Internet, in what they want and find online (Lievrouw & Livingstone, 2006: p. 50).

In contrast to other Muslim countries, in which there is a strict observance of Islamic rules, many Iranians forget self-censorship when publishing content on Facebook. They have started objecting to the government in social networks and disobeying governmental (Islamic) rules. One clear example of this relates to the use of the hijab. In their everyday life, Iranian women see each other wearing a scarf, but at the same time they feel free to share photos without the hijab on digital social networks. Many of them are not concerned about the possible aftereffects of such behavior in the workplaces or organizations they belong to; Facebook is the place for them to struggle, not only against governmental culture, but also against political and social problems. Facebook has united the Iranians living abroad, especially those once forced to leave the country due to political problems, mainly for crimes related to freedom of speech among people living in Iran. Facebook profiles of Iranians have turned into a forum for political issues, the topic which culturally interests Iranians the most (Ebrahimi & Geranmayeh Pour, 2011; Ebrahimi & Salaverría, 2014). People who had daily political discussions on the way to their workplaces, have migrated to cyberspace for a more open discussion, sharing not only comments but the latest news, videos, pictures, sounds and games.

Yee (2000) believes that online games can provide a safe space for young people to experiment with different identities and personalities without risking serious consequences. The virtual world can provide the necessary support for players in a safe space. Jaulin (2002) also believes that, through their avatars, adolescents can try outdifferent personalities and build their identities in a virtual mode without real significant effects, because in virtual worlds, failure is accepted. In virtual worlds, individuals are free to experiment with different identities; and it is not at all uncommon for them to have more than one avatar. For example, some people have one avatar that they use for work-related activities, and another that they inhabit for their personal life. They can alter their appearance, age, gender, or even choose to take non-human form. They may experiment with characters that are far from their real selves, so it can be problematic to infer the true identity of an avatar using traditional visual cues (Solomon & Wood, 2009).

2.3. Characters of virtual worlds

Like it or not, our society is morphing into a digital platform. According to the data provided by the companies, in 2014 there were more than 1.35 billion monthly active Facebook users worldwide (3Q 2014), as well as 284 million monthly active Twitter users (3Q 2014). Similar increasing figures could be seen in other social networks, such as Instagram (over 200 million active monthly users by 3Q 2014), Whatsapp (500 million users on April 2014), and others such as Viber, Myspace, Tumblr, Netlog, etc. Moreover, in some countries, national social networks are also quite active.

Indeed, the ongoing transformation of communication technology extends the reach of media to all domains of social life - personal and collective, global and local, generic and customized - in an ever-changing pattern (Castells, 2007: 239). The Internet combines the characteristics of several means of information and communication. It is a platform of interpersonal interaction and collective communication in virtual groups, but also a medium with multiple sources of information. This multiform information and communication platform also tends to determine the separation between professional and private spheres. As a result, the use of the Internet cannot be limited to a single economic model or communication format. It is not a medium but a system which is becoming as complex as society itself (Lievrouw & Livingstone, 2006: p. 201). Internet users have the opportunity not only to easily belong to communities that share their interests, but also to reshape themselves and adopt different personae for different communities and environments, experiencing moments of convergence.

2.4. Virtual culture and the Iranian cybersphere

To address the cultural question of the Internet is no easy task. Computer-mediated communication fundamentally shifts the registers of human experience as we have known them in modern society and even as they have been known throughout the ages. Time and space, body and mind, subject and object, human and machine are each drastically transformed by practices carried out on networked computers (Lievrouw & Livingstone, 2006: p. 136). To the extent that it exists, in computer-mediated communication, anonymity is used in varying ways depending on the context. In some cases, it offers users the chance to explore untried identities or to falsify the self. In other cases, it offers users the freedom to be more open and honest than they would otherwise be. In other cases still, anonymity is an obstacle to be overcome through various forms of self-disclosure. However, anonymity is not an issue, as people are corresponding with people they also know offline and building online selves that are richly contextualized in their offline social networks (Lievrouw & Livingstone, 2006: p. 43). Since the interactions in virtual environments occur online, individuals have the ability to choose how to present themselves to others, thereby enabling the creation of virtual selves that contrast with their real selves (Amichai-Hamburger, 2005). The creation of virtual identities in virtual worlds, distinct from one’s actual identity in real life, touches on the construction of human culture and the development of identity in social environments (Kafai, Fields & Cook, 2010).

The reason for choosing Facebook as the platform for this study is its popularity among Iranian users, not only in comparison to its Iranian copy, known as Facenama, but also to other global platforms like Twitter, YouTube, Instagram and others. According to Google Trends, a tool that measures the popularity of Google search-terms over time, , for searches from Iran over the course of 2014, the keyword “facebook” enjoyed an average popularity rate of 66, while the term “facenama” rated just 1. Other worldwide social networks also had low rates compared to Facebook: YouTube, 18; Instagram, 9; and Twitter, 2.

2.5 Cyberfeminism in Iranian Cyberspace

The question of how to define cyberfeminism is at the heart of the often contradictory positions of women working with new technologies and feminist politics (Braidotti, 1996). According to the latest statistics published by the Iranian Statistics Center (ISC, 2014), dating to 2012, the number of women entering university is higher than men. Thus, despite the under-representation of Iranian women in political spheres (in 2014 there were only nine women MPs and just one woman worked as a spokesperson for a Ministry in Rouhani's government), their significance in intellectual and social debates is becoming increasingly important.

In fact, women played an important role before, during and after the disputed presidential election on June 12, 2009, in organizing and leading the mass demonstrations in Iran, both through online activities as well as their physical presence in street demonstrations. Pictures, video clips and articles posted on social network sites, YouTube, blogs and international news agencies show the important role of women in civic movements, a process that was initiated years ago through various women’s NGOs and women’s rights movements as well as through independent female bloggers, lawyers and journalists in Iran (Shirazi, 2012: p. 52).

This growing importance of women in social and political debates can also be traced on the Internet. The participation of Iranian women in Facebook is not only motivated by their desire to share personal interests, but also as a way to express their opinions about sociopolitical issues. Cyberspace is regarded in Iran as an arena inherently free of the traditional gender-related constraints and struggles.

However, the Internet exists within a social framework with a number of economic, political and cultural habits that are still deeply sexist and racist. Also the Net is not a utopia unmarked by gender concerns. It is socially inscribed with regard to bodies, sex, age, economics, social class and race (Wilding, 1998: 9).

When Iranian women self-define themselves on the internet, it is still seen as a radical act to insert the word ‘feminism’ and to attempt to interrupt the flow of masculine codes in the online environment. Moreover, it seems that this behavior is above a gender-oriented act and, further still, can be defined as a sociopolitical objection presented in this way. There are more aspects of this phenomenon than just showing hair or depicting beauty.

The recurrent topics of cyberfeminism are theories of visibility of sexual differences on the Net, digital self-representation of online women as avatars and data-bodies, analyses of gender representations, and cybersex (Gajjala & Ju Oh, 2012). In any case, the self-representation of Iranian Facebook users should not be misunderstood as a sexual act, since there is no provocative content accompanying pictures, but more a need to change in offline society.

3. Hypotheses

This research project aims to understand the way Iranian female Facebook users are behaving. For that purpose, the following six hypotheses were formulated:

a) While television and radio are the places for broadcasting governmental culture, Facebook has become a space to struggle against it and a showcase for Persian popular culture.

b) Iranian Muslim women users tend to upload pictures without the Islamic hijab as their profile picture or cover photo.

c) There is a relationship between uploading pictures without the hijab and using nicknames instead of full names among female Iranian Muslim Facebook users.

d) The Facebook profiles of Iranian users usually have political contents.

e) Age is regarded as private information by female Iranian Muslim Facebook users, while birthplace and current location is not private information but in some cases a sign for other users to accept friend requests (for users who prefer to use nicknames instead of full names as their profile username)

f) There is no (or almost no) sexual content or pictures on female Iranian Muslim Facebook user profiles.

4. Research objectives

The main aim of this research is to identify the shaping of contradictory virtual identities for Iranian Muslim women users on Facebook, in contrast to their real life behavior. Iran is a Muslim (but not an Arab) country, and Persian culture, at least in some respects, runs counter to the type of behavior that the ruling government promotes. Thus, Iranian citizens tend to behave differently to people living in other Muslim countries. The governmental culture, which lays claim to the spirit of Iranian society, aims to Arabize not only modes of dress, but also the use of language and customs. The Islamization of Iran after the Islamic revolution has highly affected the social life of women in Iran, mostly as regards clothes they may wear.

In addition to that general goal, the specific objectives of this research projects are four-fold.

First, to identify the way Iranian Muslim female users benefit from cyberspace, and specifically from Facebook, in gaining a political voice. The reason that the two researchers are investigating this aspect is the increasing use of social networks in recent political uprisings in the Middle East and Muslim countries. Iranian Internet users also used Facebook as a tool to express political objection during the Green Movement uprisings in 2009.

Second, to investigate the way this group of female users deals with beauty. As an inherent dimension of women, beauty was explored because make-up, colorful clothes and short sleeves are not allowed or considered inappropriate in public places in Iran, but the behavior of Iranian users presenting pictures in the virtual world is in contrast to the governmental culture.

Third, to study how Iranian female users show their family members on Facebook.

Fourth, to research the extent of Iranian female users’ behavior in breaking governmental rules regarding the hijab or criticizing political figures, and its relationship with degrees of privacy, and changing full names to nicknames profile usernames.

5. Methodology

Online ethnography refers to a number of related online research methods that adapt to the study of communities and cultures created through computer-mediated social interaction. Prominent among these ethnographic approaches is “netnography” (Kozinets, 2010). As a play on the term ethnography, netnography designates online fieldwork that draws on the conception of ethnography as an adaptable method (Bowler, 2010, 1270).

Kozinets (2010) has written that all ethnographies of online cultures and communities extend the traditional notions of field and ethnographic study, as well as ethnographic cultural analysis and representation, from the observation of co-located face-to-face interactions to technologically mediated interactions in online networks and communities and the culture (or cyberculture) shared between and among them.

The data for this research was collected using a qualitative method from Iranian social network female users, who live inside and outside the country. In order to analyze their behavior on the Internet and the role of social networks in differentiating between Muslim women’s virtual vs. real–life identities, 550 Facebook profiles of Iranian female users were content-analyzed and the results are presented here. 50 people were selected randomly by just searching for names common among Iranian women, and then 10 friends of each of these 50 nuclear profiles were selected at random. In this netnographic analysis, the profiles of prominent political activists and celebrities were not considered; the pages are intended to represent ordinary Iranian women. Only the visible part of the pages on one screen was selected for analysis. The software used to prepare the print screen captures was Awesome Screenshot.

The researchers took into account only Facebook users with public profiles, and the account from which those screen captures were downloaded was not that of a friend or follower of any of these 550 users, nor did they have access to personal information. Only female user profiles were analyzed and their username, age, location and the URL of their public profile were recorded. The profile capturing process was completed in the first working week of February 2014. The process of analyzing the captured profiles according to the research variables, was carried out in March and April 2014.

The researchers decided to use a netnographic method for this project for two reasons. First, the researchers aimed to analyze the actions and behavior of Iranian Facebook users on their public profiles, and the best way of achieving this goal was a netnographic study. Analyzing the text and images on users profiles is first-hand information available to researchers. Second, since Facebook is a forbidden social network platform in Iran and people access it using nicknames, it is difficult to receive reliable answers through interviews alone since self-censorship is widespread in such situations.

6. Analysis

While analyzing the Facebook profiles of this set of users, the researchers decided to categorize the changes and the techniques which users make and practice in their online lives:

6.1 Usernames

The analysis shows that there is a relationship between using nicknames or shorter forms of names by Iranian users when they decide to share pictures that show them not wearing the hijab. In other words, users tend to use full names when they share pictures with the hijab, and people who have decided to share pictures without the hijab tend to use a shorter form of their names or nicknames just to make sure that their profile will not show up if somebody searches their full name.

6.2 Profile pictures and cover photos

On the main page of Facebook profiles, there are two places for users to share static pictures. The smaller one is called “profile picture”, which is normally a picture or drawing of the account holder; and the larger one, the width of the whole profile, is called the “cover photo”. The analysis of Facebook profiles showed Iranian users hesitate in choosing between their Persian or Muslim identity. In other words, it is very common to find profile pictures showing women without the hijab, but their corresponding cover photos with the scarf, or vice versa.

Young married women tend to have profile pictures of themselves alone, but share the cover photo with their husband. On the other hand, young single women generally avoid putting a picture together with their boyfriend. Although the contrary is very common in Western culture, on Iranian pages it is not. As happens in the real world, romantic relationships are likewise kept secret on the Internet in Iran.

Most young single Iranian girls tend to show personal pictures for the profile picture and for the cover photo. Some others, however, use some cultural objects like Persian carpets, the Persian alphabet, pictures of Persian poets, Persian musical instruments, the Cyrus Cylinder, etc. Meanwhile, young women with children tend to share profile pictures together with their husband, and the cover photo is left for a picture of the baby.

It is rare to find Iranian Facebook profiles without pictures. That phenomenon is much more common in other Muslim countries. When female Iranian users show an anonymous image, they use different techniques to fill the profile picture space. They may share pictures in which some elements of their faces are missing but close friends can guess who the picture is of; they may share half of the face, only the eyes, a face with sunglasses, selfies on reflective surfaces such as shop windows or ice, or may use some Photoshop filters.

6.3 Hijab and beauty

The contrast between the public rules about beauty and the personal behavior of women is also visible in the self-representation of Iranian women users on Facebook. In the past, the Iranian police have arrested Iranian women in the street who did not conform to Islamic norms about beauty. Some women wearing heavy make-up on their faces were arrested for a few hours, before their families could bring them home.

Although make-up is not acceptable in Islam, in real life Iranians spend a lot of money on cosmetic products. According to World Marketing News 2011, Iran ranked 1st and 7th in the Middle East and world as a market for cosmetics, respectively. Cosmetic surgery is also very popular in Iran.

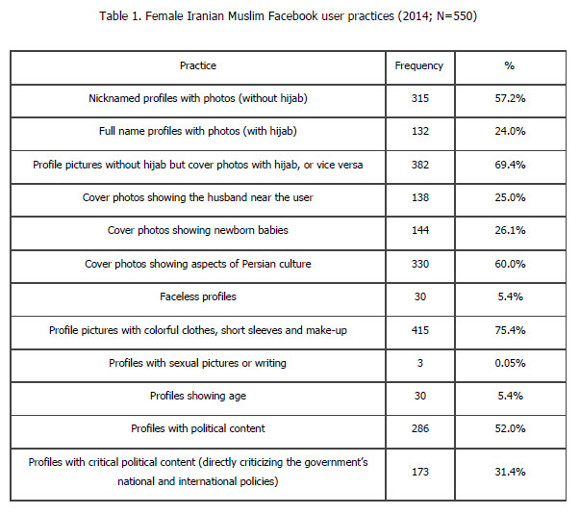

The dichotomy between public regulations and women’s habits on the Internet is evident as regards beauty. In fact, posting pictures without the scarf is not an anti-religious decision among Iranians, but an anti-government statement. Colorful clothes, short sleeves and hair uncovered by a scarf, none of which are allowed in the streets, workplaces and universities of Iran, can be seen frequently on profile pictures and cover photos. 75.4% of our sample wore such clothes.

6.4 Content

Facebook female users’ profiles show typically neutral contents such as Persian poems, birthday congratulations, love cartoons and pictures of trips. In addition, as noted above, a significant number of women - slightly more than a half of our sample - do not hesitate to express their opinions about political issues and even to criticize the government’s national and international policies (31.4%). There is no sign, however, of any sexually explicit or implicit pictures or texts on Iranian pages.

6.5 Privacy

Age is private information for Iranian women and, in fact, on Facebook public profiles, age is not shared. In contrast, birthplace and current location are not regarded as private information among Iranian women, and therefore those details are usually shared by Facebook users. Of the public profiles analyzed here, there were users who had no full name, no location, no age and no profile picture. Just a little sign was left for close friends in the choice of nickname, probably to ensure acceptance of the friendship invitation.

6.6 Political voice

While the proportion of Iranian women in Iran's government and high-ranking parliamentary positions is very low, female Facebook users have their own voices, equal to men. The details of the items investigated in the research project are summarized in Table 1.

7. Conclusions

The analysis of the data confirms the main hypothesis that a different self- representation for Iranian women is shaped in virtual worlds as compared with real life. As Baym (2000) stated, selves constructed in online groups are dependent on the norms of the groups within which they are constructed, so what is an appropriate identity in one context may not be in another. The research confirms that for Iranian users, Facebook has become a platform for objecting to governmental culture, a space to behave in opposition to what the government dictates, or to say what the government will not permit them to say. The state, traditionally the main site of power, is challenged all over the world by factors like globalization that limits its sovereign decision–making power and a crisis of political legitimacy that weakens its influence over its citizens (Castells, 2007: 240). This study shows that this is also true in Iran, at least as far as social networks are concerned.

In addition, it has been confirmed that there is a relationship between using nicknames and posting pictures without the hijab on Facebook profiles. This could be interpreted as concern about the consequences that may come of governmental limitations, religious duties or tradition. Facebook’s popularity and the enormous number of photos in its archive appear to be evidence of a culture of extreme openness, an international phenomenon in which people freely share information about themselves with others. Yet users are living in a time of heightened concern about privacy. For every user that posts pictures on the site, there appears to be others who take the information down (Wagman, 2012: 152).

We have the opportunity online not only to easily seek out communities of interest convergent with our own, but to reshape ourselves, adopt different personae for different communities and environments, and experience more of such fleeting moments of convergence. They are, nevertheless, still fleeting. It is as if a fault-line exists, and two sides grate against each other; on the one hand, is social convention, the community, the force, that binds us together as social beings; and on the other hand, is individualism, the dictum that we should just be ourselves (provided that we can discover what that is), irrespective of outside forces (Jones, 1997:29). The process of self-representation is complicated in the context of social networks, which combine a variety of audiences, of variable privacy or publicity, into a single crowd of spectators observing the same performance, but from a variety of vantage points, depending on their relationship to the performing self (Papacharissi, 2011: 209).

The contrast between Persian and Muslim identities (with the taste for Arabic clothes, words and culture) is also an aspect reflected in this analysis of women’s Facebook pages. Iranian society is acutely concerned with the Persian elements of its culture, especially Persian celebrations, customs, poems and stories, which do not normally receive the attention that Islamic elements are given by the government (state radio and television). Since there are no private media outlets in the country to support public culture, cover photos of Facebook have become a place for such expression. The forbidden platform is the place of forbidden culture, talk and images. Given that Persian users do not normally post sexual contents in Facebook profiles, the freedom that Iranian people look for online would not appear to be sexual freedom, (a phenomenon considering the fact that the public culture neither is interested); rather, the search is for greater freedom of expression, thought and behavior.

References

Amichai-Hamburger, Y. (Ed.) (2005). The social net: Human behavior in cyberspace. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Baym, N. K. (2000). Tune in, log on: soaps, fandom, and online community. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Braidotti, R. (1996). Cyberfeminism with a difference. New Formations, 29, Autumn, 9–25.

Castells, M. (2007). Communication, power and counter-power in the network society. International Journal of Communication, 1(1), 29. [ Links ]

Ebrahimi, M., & Geranmayeh Pour, A. (2011). The role of new media on public opinion during elections: the effect of Facebook and YouTube in 2009 Iran's presidential election from Iranian journalists point of view: A case study. Unpublished. Tehran Azad University, [ Links ] Iran.

Ebrahimi, M., & Salaverria, R. (2014). The Role of Social Networks in Breaking the Monopoly of State Media in Iran. Technology. Paper presented at the 10th International Conference on Technology, Knowledge, and Society, Madrid, 6–7 February 2014. Abstract available online: http://t14.cgpublisher.com/proposals/97/index_html

Facebook (2014). 2014 Third Quarter Results. Available at: http://investor.fb.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=878726

Gajjala, R. & Ju Oh, Y. (2012). Cyberfeminism 2.0. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

ISC (2014). Number of university students in Iran according to gender (1988-2012). Available at: http://www.amar.org.ir/Default.aspx?tabid=99

Jaulin, R. (2002). Anarchie en ligne. In Actes des journées d’étude: Internet, jeu et socialisation. Paris, 5–6 December 2002. Paris: Groupe des Ecoles de Télécommunication.

Jones, S. G. (1997). Virtual Culture, London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Jin, S. (n.d). The virtual malleable self and the virtual identity discrepancy model: Investigative frameworks for virtual possible selves and others in avatar-based identity construction and social interaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(6), 2160–2168.

Lievrouw, L. A., & Livingstone, S. M. (2006). Handbook of new media : social shaping and social consequences of ICTs. London; Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE.

Papacharissi, Z. (2011). A networked self : identity, community and culture on social network sites. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Shirazi, F. (2012). Information and communication technology and women empowerment in Iran. Telematics and Informatics, 29(1), 45–55.

Solomon, M. R., & Wood, N. T. (2009). Virtual Social Identity and Consumer Behavior. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Tajfel, H. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. London: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories: studies in social psychology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Twitter Inc. (2014). 2014 Third Quarter Report. Available at: https://investor.twitterinc.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=878170

Wagman, I. (2012). The suspicious and self-promotional: About those photographs we post on Facebook. In: Finn, J. M. (Ed). Visual communication and culture: images in action. Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Yee, N. (1999). Through the Looking Glass: An Exploration of the Interplay Between Player and Character Selves in Role Playing Games. Available at: www.nickyee.com/rpg/quesres.html [ Links ]

Date of Submission: May 5, 2014

Date of Acceptance: December 3, 2014

NOTES

1 This research was supported by Friends of the University of Navarra, Inc., through its scholarship program.