Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Observatorio (OBS*)

versión On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.10 no.1 Lisboa ene. 2016

News on the move: Towards a typology of Journalists in Exile

Conor O’Loughlin*, Pytrik Schafraad**

* MSc, Head of communications at Crisis Action, London. (conorlocky@gmail.com)

** Lecturer at the Department of Communication of the University of Amsterdam and associate member of the Amsterdam School of Communication Research, Kloveniersburgwal 48 1012 CX Amsterdam, Netherlands. (p.h.j.schafraad@uva.nl)

ABSTRACT

Over the last eleven years, 706 journalists around the world have been forced to flee their homelands as a direct consequence of their work. The aim of this study is to provide insight into how the experience of going into exile has affected the motivations and professional standards of these journalists. The study consisted of in-depth interviews with journalists from five countries who have previously fled their homelands. The study shows that adherence to the truth, a basic tenet of journalism in a liberal democracy, is a cornerstone of professional practice for these journalists. Journalists can be seen to have a bi-dimensional relationship with the truth, considering it an end in itself but also recognising its utility value to help further their democratising goals. Journalists' motivations were also found to be strong towards helping create a better country for their compatriots. Motivations were found to be symbolic or functional. A typology of journalists in exile is proposed. The results are discussed in the context of relevant literature on the roles of journalists in and out of democracies.

Keywords: journalism, exile, transnational, truth, motivations, norms, practices.

Introduction

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, a New York-based advocacy group, at least 706 journalists facing violence, imprisonment and harassment have gone into exile worldwide between 2000 and 2011 (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2012, 2011). The large majority, about 91 percent, have not been able to return home. Five countries—Ethiopia, Iran, Somalia, Iraq and Zimbabwe—account for nearly half the total number of journalists driven out of their countries over the past decade.

Whilst a clear distinction should be drawn between journalists in the diaspora and journalists in exile, it has been argued that expatriate communities often produce more news content on their homelands than the media community who remain. Ya’u, for example, (2008) suggests that Africans abroad produce more online content about Africa than journalists within the continent itself.

Journalists in the diaspora are also often used as commentators or sources in western media: they are familiar with the context in question; they are foreign in nature but local in proximity; and given their heritage they can lend an air of weight and legitimacy to the news proceedings.

However, speaking on the Ethiopian context, Skjerdal (2010) says, “some [journalists in exile] are politicians rather than journalists,” but to western media they are all taken as the same: “champions of the noble cause of press freedom and deserving of our unconditional support and respect” (p48). Berger (2010) describes the similar phenomenon in Zimbabwe, Malawi and Zambia of what he calls “contingent” journalists – individuals with personal or political agendas who only label themselves as journalists when it is congruent to their objectives.

However, little research has been conducted into how the process of being forced from one’s homeland and entering a life in exile might change a journalist’s conceptions of their role in society; especially their motivations and agendas and how they might be divergent with respect to the normative liberal orthodoxy on how journalists function in western, democratic societies.

The purpose of this study is to interrogate these motivations of journalists in exile with specific reference to two dimensions: those of their adherence to the truth and their motivations.

Adherence to the truth is considered a cornerstone of journalistic practice, although at the same time it is a much-contested concept (Shirky, 2014), as well as a problematic practise in many countries (see for example Hao & George, 2013). Adherence to the truth is often related to finding and publishing factual information, which is practically problematic due to limitation on the freedom of the press in many countries and contested, because what is considered factual, is (national or cultural) context dependent (Shirky, 2014; Hanitzsch et al., 2011). Nevertheless, research has shown growing intercultural consensus on the standards of truth and objectivity between Western and Middle Eastern journalism cultures (Hafez, 2002). An exploration of the place and function of adherence to the truth should draw a comparative line between the professional standards of these journalists and those standards accepted in liberal theories of journalism. Similarly, by investigating their motivations, it is hoped to explore how their experiences pre- and post-exile have affected their continued practice of journalism. By focusing on these two dimensions, a rich insight into their role conceptions, norms and allegiances can be provided.

Previous research relating to journalism in exile

Perhaps surprisingly, given their visibility and increasing numbers, little to no research exists on the norms and practices of journalists in exile. However, using extant research from other areas, we can attempt to draw together theoretical strands that help us sketch an impression of the universe they inhabit.

Just as we can now consume news produced in any corner of the globe from the comfort of our homes, globalization, media technologies and the increased movement of people mean that journalists regularly produce news from locations thousands of miles away from their stories and subjects (Klinenberg, 2005; Pavlik, 2000). As far back as 1996, Fulton argued that these changes provide journalists with “an ideal opening to try new ideas” (1996, p3). This has also fundamentally changed the practices and possibilities open to journalists in exile who may now, by utilising improved communication technologies in a way never before possible, maintain a level of expertise on their homelands and continue to practice their craft both to audiences at home (mostly through online newspapers and blogs but also through broadcast radio) and internationally (through international news outlets and acting as journalists, sources, fixers and commentators for western outlets).

Bauman (2000), a scholar with strong personal experience of forced exile himself, as well as Deuze (2006) and others, have argued that this post-geographical era of journalism is a factor of what they term respectively ‘liquid modernity’ and ‘liquid journalism’: the idea that Hallin’s (1992) ‘High Modernity’ era of journalism is finished; that the professionalisation and political consensus that existed since the end of the Vietnam war are no longer the mainstays of what has become a highly globalised, electronically connected and consumer-empowered global information system. Deuze (2005) notes that man has always had a tendency to produce news – be it gossiping in the pub, producing office newsletters on photocopiers or volunteering for the local pirate radio station. Nyamnjoh (2011) also points out that “before Citizen Journalism came to Africa, you had citizen journalists all over Africa” (p29). However, most of these practices were invisible until very recently, when the emergence of new communications technologies meant that each person’s gossip or newsletter could be delivered to the whole world via various online platforms if he or she so chose. This is a new dynamic with regard to delivery, but its seeming permanence and the ease and speed with which people have appropriated the new paradigm has brought about what Deuze calls liquid journalism: a “permanent revolution” (2006) that is now the permanent contemporary state.

Liquid journalism is central to our understanding of the transnational practices of journalists in exile as, according to Bauman (2000), it is most clearly manifest in society’s increasing uncertainty, anxiety and disagreement about the meaning, role and function of such established and traditional pillars of modern societies as journalism itself. Considering this phenomenon alongside the concurrent phenomena of (a) increased globalisation, (b) greater links and effectiveness of journalists in exile to their homelands because of technological advancements and (c) the increasing flow of journalists from their homelands due to threats and harassment (Committee to Protect Journalists Annual Report, 2011) and the role these journalists play in international and domestic discourses is made even more uncertain.

Skjerdal (2010), concerned with the specific dynamics of journalists in the diaspora, identifies three main reasons why they occupy a distinct role:

-

Their exile is likely to have been provoked by repressive or less-than-ideal conditions at home;

-

They represent an alternative to traditional media outlets in terms of content and purpose;

-

They significantly expand the potential audience base.

For journalists in exile we emphasise they are caught between two worlds and are best studied as such: they are journalists in transition. The concept of exile (as opposed to, diaspora) is at its core a temporary state, for these journalists did not choose to leave but had distance thrust upon them. Hence journalists in exile are a specific group within the diaspora. Moreover, this point is important for the following reasons.

Domestic concerns have been shown to colour the perspectives of journalists in the diaspora (Mayo, 2007). However, extant research is unaligned on the political motivations of transnational populations in general. It has been argued on the one hand that, in response to continuing globalisation 'from above' by intergovernmental institutions and multinational corporations, new political actors, acting not on behalf of a state but on behalf of a group or cause, are generating a global civil society 'from below' that challenges the authority of states (Falk, 1997; Peterson, 1992). On the other hand, it has also been argued that transnational actors can take advantage of the emerging channels and structures of the new globalised paradigm, injecting new ideas and norms in the global arena (Keck & Sikkink, 1998). Understanding the motivations of these transnational journalists is therefore important to situate them within a global taxonomy of political action and influence.

According to Freedom House, an international non-governmental organisation that focuses on democracy, political freedom and human rights, 35% of countries, but only 16% of people in the world, enjoy a completely free press. If a free press is a cornerstone of a liberal democracy, then our normative democratic standards of journalistic practice cannot therefore be universal in their application.

Thus, it must be borne in mind that when discussing journalism or journalists from non-democratic states, liberal theories of journalism, the media and culture in general do not always apply. Berger claims that, “much of this theorising—about media and democracy, the Information Society, globalization, deregulation and the Me-generation—is often conducted in splendid oblivion of conditions in the Third World” (2010, p90). Hanitzsch also sees a “cultural hegemony of Western professional norms over local modes of practicing journalism” (2007, p370), which must be recognised and accounted for in any study of transnational practices, a warning echoed by Curran (2002) and McQuail (2000), amongst others.

Similarly, in the words of Nyamnjoh: “a flexible theoretical position is needed, one which takes into account the multiple, overlapping spaces and flows in the era of globalization yet refuses to gloss over the global power imbalances and material inequalities” (2011, p20) that exist between what have become known as the Global North and the Global South.

In order to understand where journalists in exile are, therefore, it is vital to look at where they have come from and the structures and norms of journalism in the non-democratic countries from which they originate. For people living in autocratic states, journalism can have a much more basic and fundamental goal than the competing theories of journalistic purpose available to practitioners and academics in the west (e.g. Ferree, Gamson, Gerhard, & Rucht, 2000). Often, freedom of the press in non-democratic states means the basic right to circulate a ‘real’ truth unencumbered by government pressures. Although Waisbord (2007) contends that an “anti-statist spirit” (p117) inherent in discussions of press freedom in liberal democracies singles out authoritarian states as “predators of the press”, discussions with journalists in this sample align with a view of press repression being orchestrated from the highest levels.

As for how these governments’ actions affect the practice of journalism, Pintak and Ginges (2008) note that, in the Middle East context, government constraints on, and threats against, the media often lead to self-censorship as a basic survival mechanism for journalists.

Indeed, that journalists in the developing world hold differing role conceptions from their western counterparts has been repeatedly shown to be the case with journalists identifying enabling political change as an essential motive for their work in studies conducted in the Arab world (Pintak & Ginges, 2009), Cameroon (Mbaku & Takougang, 2003) and amongst Ethiopian journalists in the diaspora (Skjerdal, 2011). According to Randall, one role of journalism is to “help set the agenda for the evolution of the democratic project” (1993, p642), but how that goal is operationalised in autocratic contexts can distress the boundaries of acceptable practice.

The problem is not only ethical or ideological but also structural. According to the results from Pintak and Ginges’s pan-Arabic survey of journalists, to take just one example, “the traditional role of the Arab media as a government mouthpiece is also to blame for the shortage of quality journalists who think independently” (2009, p164). They also show that low salaries throughout the Arab world for professional journalists have contributed to a widespread flexible approach to ethics. This phenomenon is repeated in Ghana (Hasty, 2005), Cameroon (Ndangam, 2006), Russia (Levin & Satarov, 2000), Mexico and Central America (Rockwell, 2002) and many more countries.

For some of these reasons, Nyamnjoh (2011) suggests that it is wrong to simply expect or demand that non-Western journalism simply jump on board with western standards and normative ideals of journalism, because in our assumption that there is one best way to do things, we suggest that those from elsewhere must be converted to our ways. “Norms require negotiation,” he says, “especially when you are talking between societies”. He calls for the notion of flexibility to be applied – “flexible mobility, flexible belonging, flexible citizenship” (p26).

Echoing Nyamnjoh, Dutch journalist Joris Luyendijk (2006) has written that journalism to a standard expected in the west is impossible in a dictatorial regime. Skjerdal (2011) agrees, claiming that non-western journalists in the diaspora who continue to practice their craft are “occupied with something that looks like journalism” (p728). Skjerdal’s implication, however, seems to be that these are not real journalists at all, at least in the liberal democratic sense.

So what standards can we expect from transnational journalists who began plying their craft in undemocratic states? Zygmunt Bauman, in a letter to Mark Deuze, wrote that “the global, we may say, is the local without walls, while the local is the global with walls” (2007, p672). That is, in our world–now “neither modern nor post-modern”(Deuze, 2007, p672), but liquid modern–there is a fluidity of connection between all elements of our societies, but concepts are often only understood through “local”, or personal, experiences. This study will therefore attempt to provide some of what Nyamnjoh calls the necessary “room for dialogue and cross-fertilization” (2011, p23) of theories in order to open up new ways of seeing our societies – both western and non-western – taking accepted norms and theories and exploring how they might apply to journalists whose professional genesis and practice was conceived in non-democratic spheres.

Method

With this study, the line of qualitative research in this area is extended by paying attention to the motivations of journalists in exile, with specific consideration given to the interplay between their motivations and the standards they apply to their work. Semi-structured interviews were held in which interviewees were able to explain their professional histories; their changing motivations; their professional relationships with the authorities; challenges faced in their professional lives leading up to and after going into exile; and their perceptions of their work now that they live and work in different media systems. Each of the sample has between 12 and 42 years of experience as professional journalists but for the most part they have been in exile for a relatively short time, giving them recent experience of flight and fresh perceptions on their personal and professional situations.

Interviewees. Journalists who had fled their homelands as a direct consequence of their work were invited to be interviewed for this study. This paper defines a journalist as one who meets Weaver and Wilhoit’s (1996) criteria for journalists but works across any platform – television, radio, newspapers, magazines or online. Also included in the sample is a singular cartoonist (Journalist #10) whose practice certainly fulfils Weaver and Wilhoit’s description of one with responsibility for the transmission of “other information” – indeed, as far back as 1968, Brinkman (1968) showed that cartoons, when paired with editorials, have a stronger effect on opinion change than editorials alone.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (2011), five countries—Ethiopia, Iran, Somalia, Iraq and Zimbabwe—account for nearly half the total number of journalists driven out of their countries over the past decade. These five countries were the initial target for sourcing journalists to interview, but it is apparent that the situation in Iraq has improved in recent years. The decision was taken, therefore, to include Sri Lanka in the sample, a country that has seen a marked decrease in the safety and security of journalists since 20091. Journalist were approached for interviews through Committee to Protect Journalists contacts.

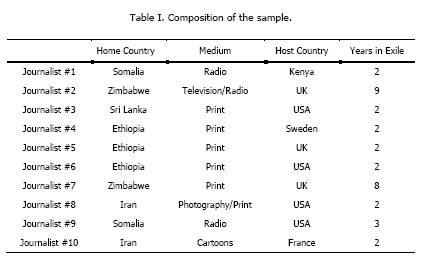

To ensure variation in the sample, purposeful sampling was used (e.g. Coyne 1997; Patton 2002) based on three main criteria: country of origin, continuation of professional practice in host countries and length of exile. Table 1 shows the composition of the sample regarding home country and length of exile, as well as host country and medium.

Journalists in the sample continue to practice their profession. Most consider their primary audiences to be those who remain in their country of origin, although a large majority (8 out of the 10) also contributes to western news outlets as contributors, commentators or fixers (arranging introductions, logistics, research, etc.).

9 of the 10 interviewees live in the Global North, with only one remaining in the Global South, namely in Kenya. In terms of their decisions to leave their homelands, 7 fled to escape violence or false charges or both and 3 left because the domestic political environment was no longer conducive to the continuation of their work.

Data Collection. The interviews were conducted by the lead author using the Skype computer programme, which facilitates face-to-face video conversations over the internet. Contact with an initial group of potential interviewees was made with help from the Committee to Protect Journalists. Subsequent interviewees were recruited through the networks of the journalists themselves. Interviews took place online at times convenient to the interviewees and lasted between 70 minutes and 2 hours each. Only interviewees who spoke fluent English were interviewed and each interview was recorded with the interviewees express permission and transcribed verbatim.

The interview guide (Gorden, 1992) contained two general questions as starting points for talking about their professional history and motivations: ‘can you tell me about your professional history?’ and ‘why did you get involved in journalism in the first place?’ The interviews went on to explore two general components: how their philosophy and practice of news production is affected by their home experiences, exile experiences and general attitudes (individual component) and their place in networks between home and host countries, encompassing diasporic networks, news relationships and contact with the home country (systemic component).

Guidelines for the analysis were derived from extant qualitative methodological literature (e.g. Berks & Mills, 2011; Charmaz, 2006; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The first step consisted of what has been called both open coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) and initial coding (Charmaz, 2006). The lead author applied codes to fragments in the transcribed interviews using a sentence-by-sentence method for generating codes. No computer programmes were used in this analysis. The coding was sensitive to the in vivo formulations of the interviewees themselves and to the meanings expressed by them. At this stage in the analysis, a priori categorisation of codes was not a priority.

The second step of the coding process is known as selective coding (Glaser, 1978), axial coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1990; 1998) or focused coding (Charmaz, 2006). During this phase, codes were gathered into four dimensions encompassing four elements of their universe: person, place, purpose and practice. After many waves of recoding and constant comparisons, a database was made of all codes broken into specific dimensions. (The code ‘revolution’, for example, was a common word used by journalists in the sample when discussing the political environment in their home countries. In this database, the ‘revolution’ code was interrogated to distinguish between three distinct utilities of the word: references to revolution as a necessity, an inevitability and an impossibility.)

The code ‘adhering to truth’ was chosen at this point as a tentative core concept for the study. Apart from the intuitive logic that suggests that this might be an appropriate choice for any study on journalism practice (as discussed in the theory section above), each of the journalists interviewed for this study repeatedly referred to the importance of sticking to the facts as the responsibility of any journalist.

Subsequently, only codes that related to ‘adhering to the truth’ were retained in the database. Numerous codes remained, however, that related to the core concept across many dimensions, such as ‘accessing information’, ‘exposing misdeeds’ and ‘acting responsibly’. A second dimension arose out of the data: aside from what could be considered the ‘how’ of the journalists’ professional practice (adhering to truth), strong concepts emerged that dealt with the motivations of the journalists, or what could be considered the ‘why’ of their professional practice. Of particular interest towards the end of this phase was the interconnectedness of these remaining codes as they began forming patterns across and within cases.

The final step of the coding process, known as theoretical or analytic coding, involved identifying and specifying the relationships between topics, concepts or variables. (Strauss & Corbin, 1998; Birks & Mills, 2011). To understand the emerging relationships between journalists, the truth and patterns of motivations, a schematic overview was produced out of the database that reported what each interviewee had said about their philosophies and practices on these two dimensions. This overview contained all concepts, measured by strength and direction, with each occurrence detailed across the chart.

An example is the code ‘acting responsibly’, which featured heavily in all ten cases. This was dimensionalised in a number of ways: as service to country; acting truthfully; acting in a vacuum of responsibility; protecting the public; responsibility of new media; acting fairly; and humanitarian concern’. The matrix graphically displayed every occurrence of each dimension, as well as the strength and direction of each mention, showing clusters and patterns within and across all cases.

Five measures were taken to assure internal validity. The first was the writing of memos throughout the study: a practice referred to by Birks and Mills as “the cornerstone of quality” (2011, p40). The lead author wrote numerous memos from the first days of the study which helped later on to map the evolution of thought, detect conceptual gaps and biases and to help mould the interview topic list as the interviews progressed. In the early stages, these memos were mostly conceptual as basic theoretical propositions were explored and the topic list was being built. Subsequently, methodological concerns dominated the memo-writing process as the interviews began to take place and, as initial coding began, the conception and management of codes became a common theme. Finally, the conceptual issues returned to the fore towards the analysis period as the body of work began to synthesise.

The second measure was the strictly verbatim transcriptions of each interview so that the quality and accuracy of the information could be ensured. In addition, where relevant, journalists’ accounts of historical events in their countries were compared against those of their compatriots to ensure consistency and accuracy.

The third measure taken was peer debriefing. The lead author discussed coding and categorisation concepts and issues with the secondary author to ensure relevance and consistency. Additionally, as a form of triangulation of interpretations (Flick 2009, p444; Wester & Peters, 2004, 193), the second author read all transcripts and codes (of all three levels) and added new codes and reflections on the original codes after the first coder’s analysis was finished. This form of triangulation serves to prevent the analysis to be influenced by individual biases or blind spots and to facilitate intersubjectivity (see Van Gorp, 2010).

Finally, categories and concepts were checked for richness and fit (Van Gorp, 2010), i.e. that conclusions were based upon multiple utterances across journalists and not just by exaggerating the relevance of individual anecdotes, quotes or examples. Some codes were given weight by the sheer volume of their occurrences but other values were accorded too, such as consistency across cases, strength of feeling/action, or conceptual clarity.

Findings

The Truth.

Journalists in the sample have a clear and unambiguous allegiance to the truth. Indeed, it might be seen as the one weapon they hold in repressive regimes. Truth in an autocracy is a precious gem: its power lies in its very scarcity. These journalists, having recognised that power, refuse to give it up. Indeed, it is this commitment to the truth that brought them to the authorities’ attention. As one journalist (#8) said: “They did not arrest me as a journalist who did nothing”.

This adherence to the truth is seen as an end in itself and an ideal towards which all journalists should strive. Typically, journalists see truth adherence as a bulwark of their personal and professional philosophy. All journalists in this sample suffered at the hands of their governments, either by threat or by actual deed. Threats could be seen as warnings of legal action or physical violence and deeds could be defined as the manifestations of those threats: physical violence, detention or even the murder of family members or colleagues. All journalists in the sample suffered these threats or deeds to a greater or lesser degree. Whether faced with threats or deeds, or both, most journalists pinpoint a moment in which a choice was made to either endure the huge sacrifice of exile or remain. Some journalists left their countries in order to avoid jail or violence, but some chose to leave as a direct consequence of their inability to waiver from the truth.

One journalist (#6), for example, said:

“I didn't want to live peacefully in my country and renounce journalism. I wouldn't be happy. That would be a triumph for them. That would be complete defeat… I liked what I was doing. I wanted to deliver truth to the people.”

Other spoke of their inability to practice a journalism of “false ideology” (#1) or that sticking to the truth is what marks out the “good guys” (#5). In some cases, journalists (e.g. #4) spoke of the inevitability that the truth would always lead to criticisms of the government; such is the pervasiveness of its power:

“In a society like Ethiopia, the government controls all aspects of life... So whether you’re writing about the quality of the art, or the music or transport, you will, at the end of the day, end up criticising government policy.”

However, as well as it being an end in itself, journalists also consider that the truth has a utility aspect. This utility can be thought of as an instrumental benefit of adhering to the truth, moving it from a purely ideological plane of conceptualism to a more grounded, practical plane. This utility can be dimensionalised in two distinct but overlapping ways: truth as a goal and truth as ameans.

Truth as a goal. In this dimension, journalists view the free flow of factual information to be a basic cornerstone of a functioning society. It is also seen as a prerequisite for learning and understanding. Journalists report that in democracies access to truth can be taken for granted but in autocracies it must be fought for. Interestingly, a number of journalists consider the west to have lost sight of the importance of truth and cite the prevalence of celebrity gossip in western newscasts to back up their assertions. Inherent in this dimension is the idea that the delivery of true and factual information to an audience is the main role of the journalist, regardless of the context. An example is one journalist (#10) who said that:

“It’s not enough just to speak on behalf of the people and reflect the view of the people back to the people. It’s a simple way to be famous. I prefer to analyse what is really happening behind the politics and I’m always searching for what is behind the government’s actions… I think it is more important for people to realise what is happening behind that curtain. It’s like a performance. Everybody is in the amphitheatre watching the performance – for me, it is interesting to go backstage and see what is happening there.”

Journalists who believe that truth is an inalienable right also tend to believe that the people, once they are furnished with the truth, should not be coaxed into any particular action or direction. They believe that it is not the role of the journalist to agitate for change or to push a people into revolution. Interestingly, even journalists who consider revolution a necessary predicate for change in their home countries (usually citing the Arab Spring as an example), none take it upon their professional selves to help make that revolution happen. Rather, these journalists believe that the truth needs to be channelled unfiltered to the people who must decide for themselves what to do with it.

For instance, one journalist (#2) takes the view that, as much as she yearns for change, it is not her role to push for it:

“All you can do is put information out there and inform people and then they have to make up their own minds. They are the authors of their destiny; they are the ones who go and vote. There’s no way an organisation, or media group, can force change.”

Truth as a means. Another dimension of journalists’ conceptualisation of the truth is that of a tool with instrumental use. Importantly, commitment to the truth is the same as before, as are the means of procurement and dissemination, but the difference lies in the intent. Journalists who subscribe to this idea are highly cognisant of the power of their work and its potential to be a driver of change, but implied within this dimension is a more active intent for that information to have a direct consequence upon society.

For most journalists, this consequence manifests as a subtle undermining of government actions or claims with the intention of drawing a contrast between establishment propaganda and the truth. Adherence to the truth helps journalists as a whole retain their integrity and consequent power, which is what Journalist #3 meant when she said that journalists must at all time be “like Caesar’s wife” (who must remain above suspicion at all times).

Using the truth as a tool is highly related to motivations of counterbalancing government claims, empowering the public and even asserting independence from political sects. A typical example of this utility is Journalist #10 who said:

“I tried to explain to the people that they needed to think differently and don’t just be like the sheep and follow the crowd… At that time, my friends told me not to publish my cartoons because they went against what people wanted. I told him I didn’t care what people wanted because I believe that what I was drawing to be true and I was sending them the truth… of course it’s a risk but it’s a risk I share with my fans. If there is no risk then what is the journalist for?”

The difference in intent can be seen in the following statement from a journalist (#6), which is typical of those who adhere to the instrumental value of truth:

“Say I have information [about economic performance]. I want to give it to the people back home so they will make a fair judgement about Ethiopia and economic development and know both sides of the story – and be sceptical of the government numbers.”

Some journalists drew a distinction between adhering to the truth in the information they gave to their audiences and how that information was procured. No journalists wavered on the idea that disseminated information should be verified and truthful. However, in asking journalists whether ‘unconventional newsgathering methods’ were ever acceptable, an example was given of a journalist pretending to be somebody else on the phone to elicit information. 4 of the journalists said that this constituted acceptable behaviour, although none of them claimed to have partaken in such activities. Each of the 4 also asserted (unprompted) that such activities are acceptable only in the specific circumstances they found themselves in, i.e. autocratic regimes. Journalist #2, for example, said:

“Because so many of these people in power are evil bastards! And if you can’t get the information in legitimate ways then sometimes you have to go the other route. Because they will fight tooth and nail to make sure you don’t find out, you don’t know [what’s going on in your country]. And I think that’s what’s wrong.”

The most common expression against this idea of a contextual approach to newsgathering techniques could be thought of as ‘the slippery slope’; a typical response in this dimension is what Journalist #7 said:

“We do have power and we have to exercise it responsibly… I don’t believe in tricking people into talking and then suddenly they find themselves in the newspaper and they thought they were talking to a friend. Where does it end? That kind of journalism is not for me.”

Motivations

Another fundamental aspect of the journalists’ driving force or motivations could be considered as the idea of being on a mission. The word mission is highly related to the idea of vocation but without the implication that these journalists were ‘born’ to practice their craft. Three of the sample, for example, pursued legal studies before they entered journalism and 9 out of the 10 journalists report that their entries into the journalistic profession had non–political roots. The concept of mission contains an innate, strongly-felt and conspicuous need to contribute to change for the good and the betterment of their homelands and people. It should not be surprising that journalists who put their lives on the line and who were forced to flee because of their profession should feel themselves to be on a kind of mission. Not all of the journalists used this word mission explicitly, but it is often implied strongly in their choice of language and explanations.

The idea of mission can be dimensionalised in two ways: symbolic mission and functional mission. These two aspects are not mutually exclusive but rather interact in complex ways on how the journalists conceive of their roles and modi operandi. Of course, journalists can also carry multiple missions but the general trend is for journalists to be more strongly situated in either the symbolic or functional dimensions.

Symbolic mission. Journalists who adhere to the symbolic mission category can be seen to be on a symbolic mission to wrest or retain control of their work and their rights as professional journalists and citizens. Included in this category are such symbolic concepts as independence, patriotism and justice.

A common feature of this category is an expressed need to remain independent of outside influences. This need is clearly a practical one but with immense conceptual implications as journalists recognise that the ice separating freedom of speech and total censorship is indeed thin. Remaining independent – and being seen to do so by both the public and the authorities – is therefore crucial to the on-going success of the media as a whole.

A typical example of a journalist who believes this element to be central to their mission (#1) felt that his job was to keep the thin ice of censorship intact:

“The government saw us as a threat… so [they said to us] you keep silent. And we couldn’t accept that as an independent radio station – which is famous – we refuse to accept. No! We are independent and we have to cover everything that we see is important that is not damaging the sovereignty of the country.”

Related to this independence (and within the same category) is a commitment to retain ideological purity. Many journalists in the sample, as discussed above, felt that they had a choice to remain in their homelands if they renounced their profession or agreed to work for government (or pro-government) media outlets. The desire to retain power over their thoughts and words and to retain the freedom to adhere to universal professional practices was a strong motivation for journalists. As Journalist #5 put it:

“I had two choices. If I were to be the government’s journalist and accept their policies and writing about it [without criticism], that would be one choice. And the second would be to do another job. But that would not work for me.”

This ‘mission’ motivation was a main deciding factor for many journalists’ decisions to leave their homelands. The strength of its ability to compel journalists to action is exposed in the fact that many journalists expressed regret that they could not overcome this sense of mission because it was the single biggest factor in their decision to go into exile.

Journalists are also motivated by a strong sense of patriotism and justice for their people. When discussing the roles appropriate for journalists in a society, giving voice to people and helping people understand their rights are two frequent reasons given why journalists do what they do.

The journalists speak of a time in their countries when the situation was better for media professionals. In fact, no journalist could speak of a worse time for journalists in their homelands than the present or recent past. These memories of a brighter dawn – often around the time of independence or the overthrow of a previous autocratic regime – have given journalists a motivating idea of helping shape their future countries. This idea has two further subcategories: a patriotism that recognises when a country and people deserve better conditions domestically and another that is more concerned with the outward-looking aspect of a country and whether it receives what some journalists consider ‘bad press’ abroad. For one example of the latter, a highly motivating factor for one Somali journalist (#9) was to educate the world “about Somalis and Somalia. So when I write for news outlets in America I try to show that the violence has not been perpetrated by all Somalis but by certain groups. All Somalis are not terrorists”.

For the former category, the stark difference between how society in their homelands should be and the actual reality is the key motivating factor here. The desire is for large-scale, macro change driven by an idea of the future extrapolated from memories of the past. Journalist #3 put it like this:

“We were always focused on a better Sri Lanka because we remember a better Sri Lanka. You see in the kinds of feature articles we did when I wrote my personal columns; we wanted to recreate that. We don't want to be barbarians any more. It was always a better Sri Lanka. We had it; we had something good. What are we doing to ourselves?”

Because of their mostly non-political origins, journalists came to realise the symbolic element of their missions later in their careers and often after a specific event. After a particularly vicious incident in Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia, in which forces of the Transitional Federal Government shot at journalists through their newsroom windows, Journalist #1 said:

“…it was at that time that most of the professional journalists of the radio fled from the capital. They fled to Djibouti, Rwanda, Ethiopia and Kenya. Most of the journalists went to Kenya. That time I didn’t flee, I remained. The radio needed to continue.”

Functional mission. This categorisation is perhaps best considered as a motivation to bring change at the societal level to benefit journalists’ compatriots who remain at home. Contained within it are the journalistic functions of advocacy, peace building and the role of the journalist as an active agent of that change. These self-assigned roles vary somewhat but can be categorised broadly into two elements: advocating and educating/empowering.

A basic, but important, mission for all journalists is to advocate for and help bring about the democratisation of their homelands. Journalist #4 put it bluntly:

“I need to see a democratic state in Ethiopia… I’m not doing journalism for the sake of doing journalism. It is my passion and it gives me a sense of mission and I want to contribute to the betterment of my society.”

Journalists express this idea as a basic function of their democratic obligations whether or not they work in democratic spheres. By implication, this frames journalists as agents for the universal democratic movement. In the words of Journalist #6: “A journalist should fight autocracy and that is a universal idea; that any political journalist wherever he might be should fight autocracy.”

This concept of an active and universal solidarity between journalists is echoed clearly by Journalist #1 amongst others when he states that:

“Every journalist is international. Journalists should form unions, should discuss this and should try to think globally, not just locally. It’s just one world, one united people. Not to say, ‘this is my interest and that country over there? I don’t care’.”

Related to the utility function of adhering to the truth discussed above, journalists who ally with this idea see themselves not as passive bystanders to societal events and trends but actors with responsibilities and obligations. When Journalist #3, for example, fled her country after her husband’s assassination she received emails from Sri Lankans telling her they felt “like orphans”.

This mission should not be misconstrued as either change for the sake of it or personal vendettas against regimes that treated these journalists badly in the past. Like Journalist #3 above, who says that she does not hate the politician who she believes ordered her husband to be killed, Journalist #6 clarifies his motivation thusly:

“I don’t have any problem with who governs the country. This country should go beyond that. We have to have a good political framework. All rights should be respected and people should have freedom of choice in government. [That] we have freedom of expression and democratic leadership. That’s my goal.”

Journalists also cite the education and empowerment of the public as a fundamentally important role for the media in developing countries where the specific contexts mean that the population is often under-educated and consequently highly dependent on the media for political information. Journalists mention the ‘information vacuum’ in which governments refuse to inform a population about political or societal developments. These journalists are strongly motivated, because of their desire to foster change but also because of their available skills, to help fill that vacuum. An example is journalist #2 who spoke about her initial motivation in setting up an independent radio station in the face of a government ban on independent broadcasting:

“The situation was getting worse and worse. It was very frustrating for me personally to not be told what was going on in my country. And there were a lot of murders going on and it needed to stop. I knew about radio so I just suddenly thought, ‘let’s challenge the government’s monopoly [on broadcasting]’.”

Indeed, many journalists believe that the on-going under-education of their compatriots is not merely a by-product of underdevelopment but a deliberate ploy to subjugate whole populations. Journalist #9 put it like this: “Journalism is needed to educate people towards the right way. When there is no government then people are left on their own to make the right decisions. And the Somali journalists are Somali citizens so we are part of that solution. We have to help the people.” Similarly, Journalist #7 said that his main motivation is to “make people – the man in the street, the man in the rural areas – be cognisant of what is going on in their country so that they can make the right decisions. They can choose people to govern them with the full facts. That’s what I strive to do”.

Some journalists are also motivated by the specific benefits brought by their medium to educate the populace. Somali journalists, for example, repeatedly mention the oral culture of their society and the specific utilities afforded by the medium of radio to disseminate educational and informative materials in a politically highly complex environment. In a similar vein, Journalist #10, the only cartoonist in the sample, is motivated by what he perceives as the specific advantages brought by his medium to help catalyse change:

“Our system cannot be corrected because there is no correction when everything is broken. So I think that the great potential of a new generation means they need to study and know how to be active politically… cartooning can be very useful because when you see a cartoon, it’s really different from an article or book. If they follow the series of cartoons, you can transfer to them some information that they really need.”

Most of the journalists’ motivations remain rooted in their home countries. This may not be surprising given the forced nature of their exile. Journalists consider themselves to be only physically separated from their home countries and that their continuing motivations ensure that their philosophies remain rooted at home. Journalist #6 explicated this idea quite clearly:

“Even though I am physically distant I am reporting information I get from that place of action back to that place of action. So basically, the virtual world has changed the context. Every morning I think about Ethiopia and think of myself as a guy in Ethiopia but not facing the constraints that other Ethiopians face... so maybe if I were in Ethiopia, living in the suburbs of Addis underground in a bunker with internet accessibility and telephone with the government not able to trace me, that's the kind of life I am leading in Britain.”

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to provide insight into the agendas and professional norms of journalists in exile by analysing their motivations and conceptions of professional standards. Banished from their homelands, none of them chose their new existences. For most of them, their new lives are temporary; for all, they are uncertain. They are, to all intents and purposes, caught between two worlds.

The interviews show that journalists have a very strong relationship with the truth, upholding all normative models of journalism. Whilst journalists hold an unwavering commitment to the truth, their reasons for doing so can vary somewhat. Some journalists are committed to the truth as an end in itself but others employ a more utilitarian view and consider the truth to be itself a tool (or even a weapon) against autocratic regimes. A minority of journalists considered ‘unconventional’ newsgathering techniques acceptable, but asserted clearly that this was a view only appropriate to autocratic contexts. With regard to journalists’ motivations, it was found that journalists in exile consider themselves to be on a mission. To varying degrees, journalists’ missions were found to be symbolic and functional.

Journalists’ stringent commitment to the truth when producing content was a stark feature of the results found. Although a minority considered ‘alternative’ newsgathering methods that may fall outside of the strict ethical guidelines of journalism in a liberal democracy acceptable, each formulated their epistemic positions firmly within their specific autocratic contexts.

As such, the distinction must be reinforced that no journalist excused the dissemination of information that was less than truthful. This might be a source of relief for Skjerdal (2011) who argued that it is not only in the interests of the news-consuming publics that information from exiled sources be accurate and impartial, but also that clear and fair information will “encourage governments and authorities to allow a public arena where opinions of all sorts can meet and be contested” (p50). ‘Good’ information will, he argues, help authoritarian regimes come in from the cold. In this regard he is full agreement with the utility function of the truth as identified in this paper.

Journalists have a clear mission, often towards the democratisation of their peoples but they still have a hard and fast adherence to the truth. In Skjerdal’s (2011) study of Ethiopian journalists, his respondents justify this double purpose of journalism and activism, claiming that their activism is focused on the need for free speech, human rights and democracy and not with party politics (2011). For Cameroonian scholar and journalist Francis Nyamnjoh, this is understandable, for ”straddling various identity margins without always being honest about it, especially if their very survival depends on it” (2011, p28) is a natural human process – one, however, that we as scholars, citizens and consumers of news would be well to be more conscious of.

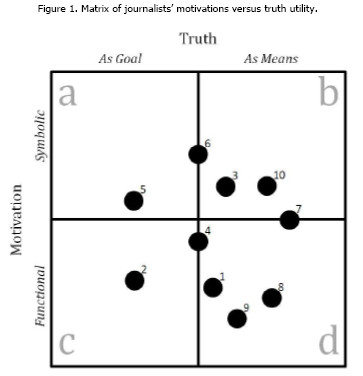

The interplay of motivation and the truth has been one of the most interesting findings of this research. In order to explicate this relationship further, a typology is proposed (Fig. 1) that places each of the ten journalists from the sample within four categories.

In this typology, journalists in the sample are organised across four dimensions according to their motivations (symbolic or functional) and their idea of truth utility (as a goal or as a means). The four resulting types of journalists can be described as idealist, pragmatist, dialogist and activist.

Type A: TheIdealist. Journalists in this category are driven by the concept of democracy and its trappings. They see truth as a fundamental right of all people and an end goal unto itself. They are motivated by the prize of gaining access to the truth and having the ability to share it when they find it.

Type B: ThePragmatist. These journalists are also motivated by the symbolic importance attached to democracy and free speech but see truth in a more pragmatic light. The truth helps them assert their independence, but also has an instrumental value to these journalists; they recognise that the truth has a power in and of itself; sometimes even as a weapon to help fight for more democracy and the trappings thereof.

Type C: TheDialogist. In this category, journalists are driven by a practical desire to improve the lives of their people through, for example, peace-building or advocacy. They see themselves as facilitators whose role is to furnish societies with the truth as a prerequisite for necessary dialogue, believing that the mere presence of the truth is itself a portent of change.

Type D: TheActivist. Also motivated by the more practical concerns of societal change, these journalists have a more active approach to using the truth, such as counterbalancing government claims or empowering the public into action. Journalists in this category feel an obligation to act as active agents of change.

In light of the preceding discussion, it should perhaps not be surprising that most journalists are to be found in and around the pragmatist and activist categories. In concordance with Skjerdal (2011), this study has found that “political change is an essential motive for their journalistic efforts” (p729). Yet this motivation is found to be strongly couched within the context of adhering to normative concerns of truth and professional practice.

There has been some debate over whether the motivations of journalists in the democratic west and in non-democratic countries of the developing world should have the same motivations at all. Indeed, some scholars have argued that journalists outside of the west should not necessarily place the goal of democratisation as their professional baselines at all, but rather should focus on the development of their constituencies in the more narrow terms of socio-economic development (e.g. Edeani, 1993; Galtung, 1990). Journalists in the sample would disagree vehemently with this sentiment, putting a high premium as they do the democratisation and political development of their nations. Journalists (especially types C and D) are also motivated by a desire to educate or empower their people, reflecting Seib’s (2008) argument that this should be an obligation of all news workers and organisations. This may also be a reflection of what Deuze calls the “slow and subtle shift” (2006, p455) of consensus in the idea of public service from top-down to increasingly bottom-up in application. Similarly, echoing Hanitzsch’s (2007) warning against the cultural hegemony of Western professional norms over local modes of practicing journalism, Berger (2008) notes that, “no-one should be surprised that it is in countries where media are the prerogative of repressive governments and/or local authoritarian elites that the quest for the Fourth Estate role of journalists is still prioritized” (p90).

It is also clear that these journalists are in the process of fulfilling Keck and Sikkink’s (1998) prediction that new communications channels would allow transnational actors to inject themselves into political debates, globally and locally, regardless of their actual location. Their enforced absence forces them to live philosophically and politically in two separate locations, but almost uniformly their primary relationship remains that which they have with their home countries. Those journalists in the sample that practice their craft for western audiences do so as analysts and commentators on their homelands and whatever political influence they wish to wield remains preoccupied with developments at home. This is not to suggest that they are oblivious or unconcerned with the journalistic practices of their adopted homes, but their focus is elsewhere. This idea of journalists caught between two worlds is perhaps best encapsulated in Journalist #6’s idea of the underground bunker (see p16).

Violence against journalists undermines the basic precept of a free press by preventing the free exchange of ideas in a society. To do so encourages self-censorship – as has been noted by our journalists – and maintenance of the status quo in contexts where the dismantling of the status quo was the desired goal. This is not a study of journalism in the developing world and, if it were, the resulting findings on journalists’ motivations and norms would undoubtedly have been quite different. It would appear that journalists in the sample have been persecuted precisely becauseof their strict professional standards and strong moral compasses.

Ogbondah (1997) suggests that the media in developing countries need to educate themselves on what constitutes democratic practice, otherwise, journalists will be unaware of normative professional boundaries and engage in irresponsible activities in the name of press freedom. However, information from journalists in this study suggests that they hold a strong sense of their purpose but also remain keenly aware of what standards are demanded of them. In truth, standards are far from disappeared. It is clear that these dearly held principles and practices were, in fact, what made these journalists conspicuous at home, marked out as ethical actors in journalistic environments with lower standards than their own: what Journalist #3 described as “being the tall poppies”.

In many senses, these journalists are the archetypal ‘liquid journalists’ as practitioners of Deuze’s liquid journalism (2008; 2007; 2005): they are not bound by geography and are constantly challenging accepted modernist norms of power, influence and position and will continue to do so in “permanent revolution” (2008, p856). Bauman, in an interview with Deuze (2007), said that whilst most journalists are “stuck inside their own myths” (p676) about what roles they play in society, the actual conversation in society has moved on. It could be argued from this study that our journalists in exile, clustered as they are nearer to the pragmatist and activist roles than the idealist or dialogist, are involved much more so in this newer, more grounded conversation; less bound-up in what journalism should be in some pearlescent democratic utopia, than what it needs to be in the harsh reality our decidedly gritty world.

It must be noted that the limitations inherent in the small sample size of this study likely affect its external validity and applicability to larger contexts. Thus, a quantitative study to investigate how much the findings around motivations and professional norms extend to a larger, more representative sample would be useful, as would a content analysis of the journalists’ work to investigate how their strong expressed ideals translate into practice. The on-average short amount of time journalists have spent outside of their countries could be counted as a liability or a benefit; a longitudinal study of journalists in exile, from early in their experiences throughout their time abroad, could prove interesting.

References

Bauman, Z. (2000) Liquid Modernity, Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Beam, R. A., Weaver, D. H., & Brownlee, B. J. (2008) Professionalism of U.S. Journalists: Have things Changed in the Turbulent Times of the 21st Century?, Paper presented to the Journalism Research and Education Section of the International Association for Media and Communication Research, Stockholm, Sweden, 20–5 July.

Berger, G. (2000): Grave New World? Democratic Journalism Enters the Global Twenty-first Century, Journalism Studies, 1:1, 81-99. [ Links ]

Birks, M. & Mills, J. (2011) Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide, London: Sage Publications, Ltd. [ Links ]

Brinkman, D. (1968) Do editorial cartoons and editorials change opinions?, Journalism Quarterly, 45:4, 724-726. [ Links ]

Charmaz, K. (2006) Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis, London: Sage Publications, Ltd. [ Links ]

Committee to Protect Journalists (2012) “Journalists in Exile 2012”: http://cpj.org/reports/journalists-in-exile-2012.pdf (accessed online 07/12/2012)

Committee to Protect Journalists (2011) CPJ Special Report, “Journalists in exile 2011: Iran, Cuba drive out critics”: http://www.cpj.org/reports/2011/06/journalists-in-exile-2011-iran-cuba-drive-out-crit.php (accessed online 14/11/2011).

Coyne, I. T. 1997. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26:3, 623–30.

Curran, J. (2002) Media and power. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Deuze, M. (2008) The Changing Content of News Work, International Journal of Communication 1, 848-865. [ Links ]

Deuze, M. (2007) Journalism in Liquid Modern Times, Journalism Studies, 8:4, 671-679. [ Links ]

Deuze, M. (2005) What is journalism? : Professional identity and ideology of journalists reconsidered, Journalism, 6, 442-464. [ Links ]

Edeani, D. O. (1993) “Role of Development Journalism in Nigeria’s Development”, Gazette, 52, 123–43.

Falk, R. (1997) Resisting “Globalization-from-above” through “Globalization-from-below”, New Political Economy, 2, 17-24.

Ferree, M. M., Gamson, W., Gerhard, J., & Rucht, D. (2002). Four models of the public sphere in modern democracies. Theory and Society, 31:3, 289-324. [ Links ]

Flick, U. (2009) An introduction to qualitative research. 4th edition. London: SAGE. [ Links ]

Freedom House (2011) Freedom of the Press 2011: Signs of Change Amid Repression: Selected data from Freedom House's annual press freedom index. Available at: http://freedomhouse.org/images/File/fop/2011/FOTP2011OverviewEssay.pdf (accessed online 12/12/2011).

Fulton, K. (1996) A Tour of our Uncertain Future, Columbia Journalism Review, 34:6, 19-26. [ Links ]

Galtung, J. (1990) The Media World-Wide: Well-Being and Development, Development—Journal of the Society for International Development, 2.

Glaser, B.G. (1978), Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of Grounded Theory, San Francisco, CA: The Sociology Press.

Gorden, R. (1992) Basic Interviewing Skills, Itasca, IL: F. E. Peacock Publishers, Inc.

Hafez, K. (2002) Journalism Ethics Revisited. A comparison of ethics codes in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and Muslim Asia. Political Communication19:2, 225-250. [ Links ]

Hallin, D. (1992) The Passing of the “High Modernism” of American Journalism, Journal of Communication, 42:3, 14–25.

Hanizsch, T. (2007) Deconstructing Journalism Culture: Toward a Universal Theory, Communication Theory, 17, 367–385.

Hanitzsch, T., Hanusch, F., Mellado, C., Anikina, M.,Berganza, R., Cangoz, I., Coman, M., Hamada, B., Hernández M.,Karadjov, C., Moreira, S. Mwesige, P., Plaisance, P., Reich, Z., Seethaler, J., Skewes, E., Vardiansyah Noor, D. & Yuen, E. (2011) Mapping journalism cultures across nations. Journalism Studies, 12:3, 273-293. [ Links ]

Hao, X. & George, C. (2013) Singapore Journalism. Buying into a winning formula. In The global journalist in the 21st century. D.H. Weaver & L. WIllnat. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hasty, J. (2005) Sympathetic Magic/Contagious Corruption: Sociality, Democracy, and the Press in Ghana, Public Culture, 17:3, 339–69.

Kester, B. K. (2010) The Art of Balancing : Foreign Correspondence in Non-Democratic Countries: The Russian Case, International Communication Gazette, 72:1, 51-69. [ Links ]

Klinenberg, E. (2005) News Production in a Digital Age, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 597, 48-64. [ Links ]

Levin, M. & Satarov, G. (2000) Corruption and institutions in Russia, European Journal of Political Economy, 16, 113–132.

Louw, E.P. (2004) Journalists Reporting from Foreign Places in A.S. de Beer and J.C. Merrill (Eds.) Global Journalism: Topical Issues and Media Systems. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Luyendijk, J. (2006) Het zijn net mensen. Beelden van het Midden-Oosten [People Like Us: The Truth about Reporting the Middle East]. Amsterdam: Podium.

Lyons, T. (2007) Conflict-generated diasporas and transnational politics in Ethiopia, Conflict, Security & Development, 7:4, 529–549.

Keck, M. & Sikkink, K. (1998) Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Mbaku, J. M. & Takougang, J. (2003) The leadership challenge in Africa : Cameroon under Paul Biya, Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

McQuail, D. (2000) McQuail’s Mass Communication Theory, London: Sage.

Nyamnjoh, F. B. (2011) De-Westernizing media theory to make room for African experience in Wasserman, H. (Ed.) Popular Media, Democracy and Development in Africa, Oxford, UK: Routledge.

Ndangam, L. N. (2006) ‘Gombo’: Bribery and the corruption of journalism ethics in Cameroon, Ecquid Novi: African Journalism Studies, 27:2, 179-199.

Ogbondah, C. W. (1997) Communication and Democratization in Africa. Constitutional changes, prospects and persistent problems for the media, Gazette, 59, 271–94.

Patton, M. Q. (2002) Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Third edition, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pavlik, J. (2000) The Impact of Technology on Journalism, Journalism Studies, 1:2, 229-237. [ Links ]

Peterson, M. J. (1992) Transnational Activity, International Society and World Politics, Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 21, 371–88.

Pintak, L. & Ginges, J. (2009) Inside the Arab Newsroom, Journalism Studies, 10:2, 157-177. [ Links ]

Pintak, L. & Ginges, J. (2008) The Mission of Arab Journalism: Creating Change in a Time of Turmoil, The International Journal of Press/Politics, 13, 193. [ Links ]

Randall, V. (1993) The Media and Democratisation in the Third World, Third World Quarterly, 14:3, 625-646. [ Links ]

Rockwell, R. (2002) Corruption & Calamity: Limiting Ethical Journalism in Mexico and Central America, Global Media Journal, 1:1, http://lass.calumet.purdue.edu/cca/gmj/OldSiteBackup/SubmittedDocuments/archivedpapers/fall2002/rockwell.htm (accessed online 19/11/2011).

Seib, P. (2008) The Real-Time Challenge: Speed and the Integrity of International News Coverage in Perlmutter, D. & Hamilton, J. M. (Eds.) From Pigeons to News Portals: Foreign Reporting and the Challenge of New Technology. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press.

Shirky, C. (2014) Truth without scarcity, ethics without force. In The new ethics of journalism. Principles for the 21st century. K. McBride & T. Rosenstiel. Los Angeles: SAGE: 9-24. [ Links ]

Skjerdal, T. S. (2011) Journalists or activists? Self-identity in the Ethiopian diaspora online community, Journalism, 12:6, 727-744. [ Links ]

Skjerdal, T. S. (2010) How reliable are journalists in exile? British Journalism Review, 21, 46-51. [ Links ]

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (2nd Ed.), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990) Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Van Gorp, B. (2010) Strategies to Take Subjectivity out of Framing Analysis. In Doing news framing analysis. Empirical and theoretical perspectives. P. D'Angelo and J. A. Kuypers. New York, Routledge: 84-109. [ Links ]

Waisbord, S. (2007) Democratic Journalism and “Statelessness”, Political Communication, 24:2, 115-129.

Weaver, D. H., & Wilhoit, G. C. (1996). The American Journalist in the 1990s: U.S. News People at the End of an Era, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Wester, F. & Peters, V. (2004) Kwalitatieve Analyse. Uitgangspunten en procedures. Bussum: Coutinho . [ Links ]

Ya’u Y.Z. (2008) Ambivalence and activism: Towards a typology of the African virtual publics. Paper presented at the 12th CODESRIA general assembly, Yaoundé, Cameroon, 7–11 December. Available at: http://www.codesria.org/IMG/pdf/Y-Z-_Ya_u.pdf (accessed online 14/10/2011).

Date of submission: March 22, 2015

Date of acceptance: January 5, 2016

Acknowledgements

The help of the staff of the Committee to Protect Journalists in New York was invaluable throughout this study. Most importantly, the authors would like to sincerely thank the journalists in the sample, who gave so generously of their time and their incredible stories.

END NOTES

1 The interviews were conducted in the last months of 2011. Following this logic, currently Syria would be one of the 5 most relevant countries (see CPJ website).