Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.10 no.4 Lisboa dez. 2016

Going Viral: News Sharing and Shared News in Social Media

Ingela Wadbring*, Sara Ödmark**

* Nordicom University of Gothenburg, Sweden (ingela.wadbring@nordicom.gu.se)

**Media and Communication Science, Mid Swden University, Sweden (sara.odmark@miun.se)

ABSTRACT

Through the advent of social media, news achieves a life of its own online. The media organisations partly lose control over the diffusion process, and simultaneously individuals gain power over the process, and become opinion leaders for others. This study focuses on news sharers and news shared (or rather, interacted), and has three RQ:s: 1) What characterizes the people who share news in social media, 2) Have the characteristics of interacted news changed over time? and 3) Are there differences between news content interacted by ordinary people and news highlighted by media organisations? Two different studies have been conducted: A representative survey and a quantitative content analysis.

The main results are that the opinion leaders differ from the majority by being younger, with a greater political interest, single and more digital in their general lifestyle, both concerning news consumption and other aspects. The content analysis shows that the most interacted news on social media follow the traditional news values rather well, with a few exceptions. Most apparent is that interacted news is more positive over time and compared to print front-page news. Accidents and crime dominate print front-pages, while politics is more prominent in interacted news.

Keywords: opinion leaders, news value, survey, quantitative content analysis, online news, offline news

Introduction

Some news takes on a life of its own. A chronicle with the headline We don’t need another diet advice (Skäringer, 2014), was shared, liked and commented on more than 75,000 times in one single day in 2014. The chronicle has popped up now and then ever since. Another example is a story from 2005 about a 15-year-old boy who was dying of cancer, which became viral many years after its first publication. In 2012 the story was read by 700,000 people (Liljemalm, 2014). Sharing, liking and commenting on news on the Internet can be characterised as something that occurs in the digital borderland between private and public. Online we find the traditional news organisations, side by side with non-traditional news organisations such as Buzzfeed or Upworthy. We also find ordinary people who publish their own content or share that of others.

Even though a lot of the viral content originates from traditional media organisations, those companies have partly lost control of the publication process and it has become increasingly common for news to be forwarded by a friend on Facebook, a well-known person on Twitter, or through a link in a forum such as Reddit. This means that rather than actively seeking news from a news organisation, news simply appears in the audience’s digital flow, through one’s own accumulated network. It is clear that this transformation will modify the news process forever, even though we are only at the beginning of a new era (e.g., Bakker, 2012; Costera Meijer & Groot Kormelink, 2014; Hermida, Fletcher, Korell, & Logan, 2012).

The digital borderland can be characterised as a slow transformation from the distribution of media content to the circulation of media content. The essence of the traditional media companies has been mass-produced and mass distributed content, whereas circulation is more important in a participatory culture (Jenkins, Ford, & Green 2013). The logic behind distributed content and digitally circulated content differs. Media organisations usually design their websites with the intention that people should easily find them, stay on the sites for as long as possible, and, as a target group for advertisers, be measurable. Circulation is based on different principles that take advantage of new technology in order to circulate content in social forums. It is the general public, rather than the media organisations, that are important. The division of roles between producer and consumer is no longer clear (Jenkins et al., 2013; Lee & Ma, 2011; Ritzer, Dean, & Jurgensen 2012).

In Sweden, the traditional media organisations remain strong. Sweden could be characterised as a democratic corporatist media system (Brüggeman, Engesser, Büchel, Humprecht, & Castro, 2014; Hallin & Mancini, 2004), with a strong newspaper tradition, an historically strong political parallelism, a professional and self-regulating journalism, and a long history of public service broadcasting without competition. Together with the other Nordic countries, Sweden is a highly digitalised country: more than 90 per cent of the inhabitants have access to the Internet, 80 per cent use it on an average day, and more than 50 per cent use social media on an average day (Nordicom, 2016).

In addition to producing traditional news content, some of the Swedish media organisations have established specific viral sites in order to keep up with development and to try to increase the circulation of content online: for example, www.omtalat.nu (by Bonnier), or www.lajkat.se (by Schibsted). The role models used are American, such as Buzzfeed or Upworthy, with their tabloid form of content that fits well with dissemination. It is, however, also possible to identify external challengers to the media organisations. With the exception of bloggers, who can receive immediate impact with a single post, other entrepreneurs have developed a structured way of disseminating viral content. These kinds of sites developed in Sweden in 2014 and, depending on how they are defined, in 2015 there were around 20 to 25.

The interactive news online is of interest to study since both the news distribution and news use are undergoing change. The concept of interacting is here used as a general term for sharing, liking, and commenting on news. In this study the concept of social media refers Facebook and Twitter. We approach the phenomenon of interacted news from different angles, and our three research questions can be posed as follows:

RQ 1: What characterises the people who share news in social media?

RQ 2: Have the characteristics of interacted news changed over time?

RQ 3: Are there differences between news content interacted by ordinary people and news highlighted by media organisations?

Our theoretical bases are, first, concerned with diffusion and opinion leaders; that is, people who share news online, and second, the traditional and digital news values in the media, both online and offline. Two different studies have been conducted: a representative postal survey, respectively a quantitative content analysis, both online and offline.

Theoretical perspectives

Media is of great importance for gaining knowledge about events we have not experienced ourselves. Yet the media is not the only channel of significance. People around us have long been as important as the media. We discuss with people, and we listen to other people’s experiences and opinions (Bro & Wallberg, 2014).

Studies of the role of opinion leaders in elections were conducted in the US in the 1940s and the 1950s (e.g., Katz & Lazarsfeld, 1955) and the general concept they used for this process was the two-step flow hypothesis. The concept of the two-step flow hypothesis is still in use, even though it was introduced over 60 years ago. A lot of the studies that use this concept are concerned with political opinion (e.g., Dubois & Gaffney, 2014; Ma, Lee, & Goh, 2014) or marketing (e.g., Kaiser, Kröckel, & Bodendorf, 2013; Shi & Wojnicki, 2014). For both perspectives it is relevant to understand the influence in general, as well as the personal influence on others, who the opinion leaders are, and how they behave. From our point of view, most relevant is attached to identifying the opinion leaders. What are their characteristics?

One way to identify the opinion leaders is to use the classical theoretical model of diffusion of innovation, which is concerned with how people adopt and embrace innovation, and also how they become ambassadors for it. This can be about the introduction of new forms of seed as well as the use of new technical platforms or the dissemination of news (Ma et al., 2014; Rogers, 2003; cf. Carey & Elton, 2010). Opinion leaders who share news are likely to be early adopters, and the theory of diffusion of innovation has been found to be relevant as an explanation for sharing news (Ma et al., 2014).

The theory of diffusion of innovation is concerned with the behaviour of the general population. The innovators are the first ones to embrace new innovations. They are usually very few in number. Together with the visionaries the group accounts for about 15 per cent of a population, referred to as the early adopters. Thereafter come the early majority (the pragmatists) who accept the innovation, and then the late majority (the conservatives), who follow the early majority. The sceptics are laggards who are not at all interested in innovation.

The sections of the population that are of interest for this paper are the innovators and the visionaries, that is, people who are early adopters, and we intend to compare them with the majority, that is, the rest of the population in this study. The early adopters—or opinion leaders—are usually characterised by, for example, high education, technical skills, positive attitude toward change, and a high degree of involvement with society (Ma et al., 2014; Rogers, 2003; cf. Jenkins et al., 2013).

Previous research shows that opinion leaders influence people who are information-seekers and who are more likely than others to share news in social media (Kim, Chen, & de Zúniga, 2013; Lee & Ma, 2011; Ma et al., 2014), and that the strongest predictor for sharing news is ones own news consumption online, but also friending journalists or news organisations (Weeks & Holbert, 2013).

Compared to the offline world, it is possible to identify effects on the opinion of network members when people interact on social network sites (Kaiser et al., 2013). Some scholars even suggest that it is possible to stop negative opinions from spreading if one is able to address opinion leaders (Kaiser et al., 2013). The specific opinion leader traits discussed by Katz and Lazarsfeld sixty years ago (1955)—having a following, being seen as an expert, knowledgeable, and social embeddedness—have been tested in an online environment, and researchers have found that close interaction is important, and that followers are more important than experts (Dubois & Gaffney, 2014). On social network sites, social embeddedness can be regarded as a precondition. Thus, a two-step flow hypothesis in combination with the theory of diffusion of innovation seems relevant for this study.

The second part of this paper is concerned with the criteria for news value that is used by both the early adopters and also among the journalists in news organisations. Since a family member or a friend can be the gatekeeper, rather than a journalist, the news value criteria might differ from those of the professionals. Many of the criteria for news values were formulated in the 1960s; criteria that still exist and are used today (Bro & Wallberg, 2014). The news value criteria are almost entirely built upon the empirical work of the output of news. An overview of the most important criteria can be summarised as follows (Ghersetti, 2012, p. 212ff):

- Proximity: events close in time, space, and culture more often become news items than events far away in time, space, and culture.

- Sensations and deviations: events that are negative, unexpected, unforeseen, and odd more easily become news items than events that are positive, expected, foreseen, and normal. Therefore content that is often prioritised is accidents and crime, celebrities, and sports.

- Elite centring: people in news items often represent a political, economical, cultural, or athletic elite, rather than common people.

- Simplification: events that are too complicated have difficulties in breakthrough.

Furthermore, different types of content fit with different forms of media, for example, frequency, available space, and the possibility of using moving images. This is the outcome of what has passed through the gatekeeper—or rather the gatekeeping process—in news organisations (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009).

Concerning the digital dissemination of news, it is not appropriate to talk about common news value criteria in the same way as for traditional media, since it does not necessarily involve an organisation with professional, shared values behind the spread of news. However, it seems that there are other, specific characteristics for content—but not necessarily news content—that are disseminated online. There are some technical conditions of importance, such as easily accessible, portable, included in a flow etc. Some specific traits are also identified, although some of these are difficult to measure. Despite the objections made, we will use some of the traits that can be tested and analysed also in a quantitative way (Jenkins et al., 2013, p. 237ff):

- Content that can provide shared experiences, either in the form of values and/or nostalgia, or in the form of strengthening social ties.

- Humorous content that can be immediately understood by everyone, or parodic content that is build on common references and thus cannot be understood by everyone.

- Content that is incomplete in one way or another, which can involve users in a dynamic way.

- Mysterious or rumour-based content, where it is unclear whether it is true or false, whether it is commercial or not, or if the content is kept alive because someone wants to cause uncertainty about events or phenomena.

- Controversial content, that is, content that can trigger debates or is built on conflicting values.

Previous research about disseminated news has differed in nature and found varying results. In an American study about news consumption on Facebook, the interviewees were asked to define ‘news’; the responses were broad: whatever, the whole Internet, or things that are of interest (Erdelez & Yadamsuren, 2011; Gottfried, Guskin, Kiley, & Mitchell, 2013). Another study shows that the preferred online content was professional journalism, characterised by core journalistic value (Neuberger, 2014). Yet another study researched how content from traditional media is spread in social media and found that around 40 per cent of the content in traditional media is not disseminated in social media. It is content from single sold tabloids that is spread the most, and almost half of the shared content was about politics. However, the single most shared article was about something completely different, and had the headline Beer makes men smarter (Bro & Wallberg, 2014).

Method and material

The empirical work for the first research question is based on data collected from the so-called National SOM Survey (Society, Opinion, Media). The SOM Institute is an independent research organisation within the University of Gothenburg that has been conducting representative surveys since 1986. A SOM questionnaire is about 20 pages in length and contains between 80 and 100 questions about political opinions, media habits, political orientation, etc., along with a large number of questions about personal background. We used one of five editions of the 2013 survey. The fieldwork was conducted between September 2013 and January 2014 and took the form of a printed, postal questionnaire, a method that still function very well in Sweden.

The sampling method used was systematic probability sampling, and in 2013 3,400 people aged 16 to 85 years, living in Sweden, received the survey reported in this paper. The response rate was 53 per cent, and the respondents are representative in terms of gender, social class, and level of education. Older people are slightly over-represented since the response rate in the youngest groups was below average (Vernersdotter, 2014).

Our analyses are based on one question that is used as a dependent variable in the survey: ‘Have you, during the last 12 months, shared any of the following content from newspapers, radio, or broadcast in social media (for example, Facebook, Twitter)?’ The items provided were ‘culture’, ‘entertainment’, ‘debate’, ‘politics/economy’, ‘accidents/crime’, ‘sports’, and ‘lifestyle’. The response options for each item were ‘no, never’; ‘yes, once’; and ‘yes, several times’. For the analyses, we built one single dependent variable: respondents who had shared any kind of news several times are what we call digital opinion leaders. The rest of the population is called the majority.

Along with questions about sharing news in social media, the survey contains demographic data as well as data about interests and life style, news consumption, Internet use, etc. We use some of these questions as independent variables in the analyses.

To answer our second research question we first used the newsletter socialanyheter.se. Every day socialanyheter.se collects the most interacted news items in social media and sends out a newsletter to subscribers with links to the specific news items. Our analysis is based on the single most interacted news item each day.

Some comments about this material need to be made, not least to identify the limitations of the material and thus to make the study clear. The sources used in socialnyheter.se are a selection of Swedish media sites: from the big national media sites and industry sites to alternative and local media sites. In this case, social media refers to Facebook and Twitter. Interaction includes a mix of sharing, liking, and commenting. It is possible that a large amount of comments on a news item on Facebook is the result of a huge circulation, but it can also be the result of people excitedly discussing an issue. Other studies indicate that it is as common to share as it is to like or comment (Bro & Wallberg, 2014).

In order to be able to analyse whether the news value criteria differ between digital opinion leaders and gatekeepers in the media organisations, we also conducted a content analysis of the front-page main news item of the tabloid Aftonbladet. The article connected with the major headline of the print edition of Aftonbladet was coded with the same variables as the most interacted news items in social media, according to socialanyheter.se. Aftonbladet was chosen because it is the biggest newspaper in Sweden, print and online taken together, and also because previous studies show that tabloid content is the most spread content online (Wadbring & Ödmark, 2014). This is therefore a relevant comparison.

Using a quantitative content analysis we analysed the most interacted news items on each day for the first five months in 2014 and 2015. The printed version of Aftonbladet was only analysed in 2015. A few days are missing from the analysis because the news items had either been removed or placed behind a pay wall. A total of 297 digital news items were analysed. For the printed Aftonbladet, 150 news items were coded. The number of variables used in the content analysis is 14, and they measure different aspects of news value criteria and news topics. All definitions can be found in Appendix 1.

Two things are important to know about our measured period. First, in the spring of 2014 two elections were near: in May 2014 Sweden had elections to the European Parliament and, later in the fall (September), to the Swedish Parliament. Second, the big national viral sites developed during the time between our measured periods.

The same person carried out all the coding. Some of the news value criteria were comprised of more interpretations than others. We conducted an intra reliability test on five per cent of the digital material, and the result was that five of the variables each received one coding error. This means that even though the variables needed interpretation it was possible for one person to be consistent in the coding.

How valid then is our material and, therefore, our results for the three research questions? Surveys produced statistically significant data. However, as with other statistical surveys, this one provided a general picture. The methodological choice cannot, therefore, provide more in-depth information about how and why people share news. The quantitative content analysis entails other problems as well as the lack of in-depth information. The material collected by socialanyheter.se mainly originates from traditional media companies. On the other hand, it is reasonable that this is the material that really is the most interacted since there are few independent news sites in Sweden. The most dominant viral sites, omtalat.nu and lajkat.se, are also included.

We want to emphasise that this study is not a complete overview of news stories with great social impact, but it is a glance at the most interacted news items each day in a specific country—the tip of the social news iceberg in Sweden if you will.

We would also like to include a few words about the limitations of the study. All studies suffer from weaknesses and ours is no exception. First, when using a standardised questionnaire it is impossible to say anything in-depth about the informants. Instead, we can provide a broad and general picture. Studies like ours need to be supplemented with more qualitative oriented approaches. Second, the question in the form used for RQ1 was not formulated for this study, but used as secondary data. It is useful for our purposes but could have been posed in a better way. Third, the results from the coding in the content analysis are probably, at least to some extent, dependent on the coder. Even if an intra reliability test was conducted and found to be reliable, an inter reliability test might have produced different results. We are, however, convinced that the overall findings are reliable, not least because the variable values were limited and the definitions were determined beforehand. Fourth, we are aware that we may have attempted to achieve too much with this study, with three highly disparate research questions. However, our intention is to provide a broad overview of the phenomenon of news sharing and shared news. We hope that other scholars deepen the understanding that is schematically presented here.

Findings

Our first research question is about the news sharers. What are their characteristics? First, according to the definition we used, about 12 per cent of the population can be regarded as news sharers: sharing some kind of news several times in the last year. This result is similar to a study conducted by the PEW Research Centre, which found that around 10 per cent of Facebook users shared news ‘often’ (Gottfried et al., 2013). In keeping with Rogers (2003), this group can thus be identified as embracing something before the majority of the population, as the digital opinion leaders.

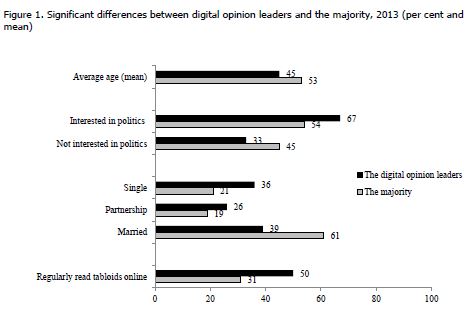

In comparison to the majority, a description of opinion leaders shows that they are younger, have a higher educational level, higher political interest, hang out with friends more often, are unmarried, frequently read tabloids online, and do not have children in the household to the same extent as the majority. Since it appears that some of these features can covariate, we conducted a logistic regression analysis. The specific features that remain when controlled for each other are shown in Figure 1.

Only three demographic factors were significant: age, political interest, and marital status. With regard to media consumption, only frequent reading of tabloids online was significant. It is worth mentioning, however, that the most used news source online in Sweden is a tabloid: Aftonbladet. According to the KIA Index, which measures unique visitors to web sites, Aftonbladet has around five million unique visitors a week, whereas the second most visited site has approximately three million unique visitors a week (Kia Index, 2015).

The digital opinion leaders are, on average, 45 years old (the age range for the survey is 16–85 years), as compared to the majority with the average age of 53. The digital opinion leaders are more interested in politics, more often unmarried, and they are frequent readers of tabloids online. Half of the digital opinion leaders read tabloids online at least three times a week. Thus, compared to the rest of the population, the digital opinion leaders demonstrate certain personal characteristics, as well as differences in media consumption.

Another way to understand the characteristics of the digital opinion leaders is to analyse their general behaviour online. Some questions about online behaviour are posed in the SOM survey. There are significant differences, in all cases, between the digital opinion leaders and the majority (Figure 2).

The differences between digital opinion leaders and the majority are rather large. The largest difference concerns the activity in social media. Three quarters of the digital opinion leaders use social media several days a week, but only one third of the majority do so. Another large difference concerns the use of music services online—mainly Spotify—with a difference of 21 percentage units. We can thus conclude that the digital opinion leaders are much more active online than the majority, which is hardly surprising.

Our second and third research questions refer to the interacted news. In the wide selection of news sources and the massive amount of news stories published each day, what characterises the news that gets through, and the news that gets shared, liked, and commented on more than other news?

Before we turn to the research questions about news value criteria and news content, it is useful to know that in 2014 64 per cent of the analysed news, and in 2015, 68 per cent was originally published in the tabloids online, or in the tabloid’s viral sites, prior to being shared and interacted upon. We are thus mainly concerned with tabloid content in the most interacted news. In 2014 the specific viral sites were non-existent in our source material, but by 2015 about 20 per cent of the most interacted news came from viral sites. In 2014, 41 per cent of the analysed news was opinionated material, such as columns, chronicles, and opinion editorials, whereas in 2015 this was 27 per cent.

The following three figures have the same structure: all figures contain two comparisons, the first between the most interacted news in 2014 and 2015, and second between the most interacted news and the main news story in an offline tabloid in 2015. The text also follows this pattern.

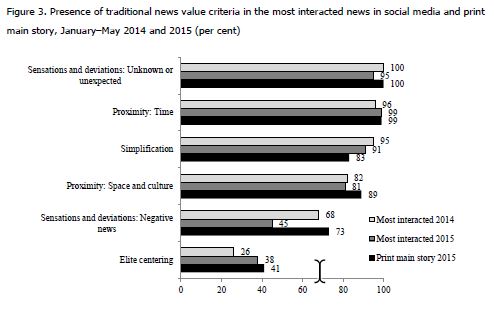

We begin with the online comparison over time. Knowing that the most interacted news comes from traditional news producers, the traditional news values should remain strong, and they do (Figure 3).

A large majority of the reviewed news items online, for both years, can be characterised as unknown and/or unexpected, presented in a simplified way, with proximity in time, space and culture to the Swedish news consumer. This is not surprising since sensation and deviation in this coding is less about extreme abnormalities and more ‘assumed to be previously unknown’, which is merely the definition of a news story. The same applies for proximity in time, which also falls under a basic, general definition of news. Simplification in this case means the item shows a depiction of one aspect of a news story, which usually comes down to having chosen a single story angle—an everyday journalistic approach. In spite of the globalisation of news and the news producers’ access to stories from around the world, the proximity in space and culture is still apparent at around 80 per cent.

However, an interesting difference over time can be observed when it comes to negativity (p<.01). Traditional news values criteria state that negative news is favoured over positive news, which was also the case for the year 2014. But here we can see a clear shift from nearly 70 per cent negative news in 2014 to only 45 per cent in 2015. The explanation for this difference is most likely the new viral sites and their impact on the traditional news organisations when it comes to finding stories that are inspirational and uplifting—and spreadable. A news story that can exemplify this is the most shared news item of 16 May, 2015, from www.omtalat.nu: She is 18 years old, has Downs syndrome and wants to be a model—her story is amazing. This type of non-traditional headline phrasing would have been much more unlikely in 2014, prior to the introduction and success of the national viral sites.

Another difference over time is an increase in elite centring from 2014 to 2015 (p<.05). Since the elites in question are often are top politicians or entertainment or sport celebrities, we can see a slight increase over time in interest in and focus on such well-known figures.

Turning to the comparison between online and offline news (Figure 3) there are few differences. Most interesting is the difference in negativity (p<.01). The most interacted news has developed in a more positive direction over time but the printed news is still rather negative. This result might say something about the attitude towards positive and negative news that is different between the digital opinion leaders and the journalists, but this needs further research to be confirmed.

The elite centring in the most interacted news from 2015 was no more significant than in the main print news story, which means that even though there was an increase in elite centring over time in social media, the social media does not seem to be more celebrity-focussed than traditional print news.

In general, the traditional news value criteria appear to be rather similar to the most interacted news online and the main news story in print tabloids, with the exception of negativity.

The features of digital disseminated material online presented and discussed by Jenkins et al. (2013) provide the basis for the next comparison. A reminder is that the origin of the features for dissemination of digital content refers to content in general, that is, not specifically about news. However, we have also attempted to analyse these features for news.

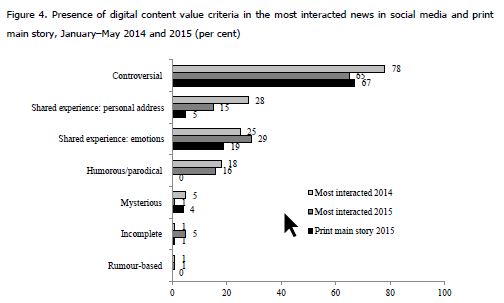

We find that one of the main significant criteria for both years concerning the most interacted news item is the possibility of causing controversy. This was most apparent in 2014 when 78 per cent of the interacted news might cause opposing opinions or outrage but, at 65 per cent, it was also high in 2015 (Figure 4). The gap can be explained by the less political and more positive news in 2015 (p<.05).

Shared experience is the most difficult criteria to address without asking the senders themselves about the reasons behind their interaction. In this case we tried to dissect the material itself by posing two different questions: Is the news story designed to move the consumer, through, for example, the use of nostalgia, sentimentality or an uplifting message? and Does the news story address the consumer in an inclusive and/or personal way with an assumed intent of being relatable? As can be seen in Figure 4, the most interacted news in 2015 was less inclusive (p<.01) but slightly more sentimental than the news in 2014. The lower rate of personal address in 2015 can probably be explained by the lower percentage of opinionated material that year, since opinionated material is more likely to engage in personal address than traditional news.

Close to a fifth of the most interacted material in both years could be characterised as humorous or parodical, whereas the rumour-based, incomplete or mysterious material was hardly represented at all. The explanation for the latter is probably the fact that it is mostly traditional news organisations with traditional journalistic ethics and methods that are included as sources, even in the online material.

Turning to a comparison between online and print, the digital news value criteria are similar in regards to controversy, whereas the most interacted news in social media is more personal (p<.01) and emotional (p<.05) than the printed Aftonbladet. However, the differences are not very large. The main stories in the printed tabloid show personal address to a low extent, probably because opinionated material is rarely published as the main news story on the front page.

Rumour-based, incomplete and mysterious news are somewhat equally absent, both in the printed paper and in the most interacted news, whereas the difference in humorous or parodical material is clear: humour is non-existent in the major front-page story in the printed Aftonbladet but accounted for 16 per cent of the most interacted news on Facebook and Twitter during the same period (p<.01).

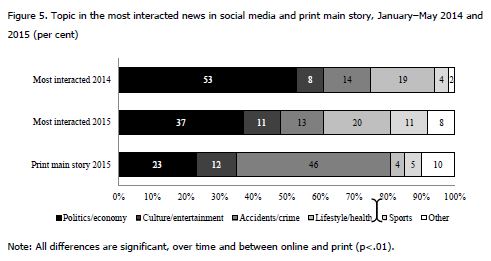

A further interest in the second and third research questions lies in the topics presented. Are there any differences in news topics? We begin with a comparison between the most interacted material in 2014 and 2015 (Figure 5).

It is clear that the elections in 2014 had an impact on what is most interacted in social media. Politics occurs more frequently in 2014, and represents more than half of all the news items. The main topic within politics was racism. The Swedish party, Sverigedemokraterna, a right-wing party with one main issue on their agenda, the immigration issue, grew considerably: first in the election to the EU Parliament, and later in the national election, when it became the third largest party in Sweden. Thus, this became a topic in itself. In 2015 the political material decreased in favour of sport material, partly due to the World Ski Championship in Falun, Sweden.

Although the differences between the most interacted social media news and the print news were not very substantial regarding basic news value criteria, there is a huge difference when it comes to news topics. The lead story of the front page of Aftonbladet in print was categorised as accidents/crime in nearly half of the cases in the spring of 2015. Only 13 per cent of the most interacted news items in social media were about accidents and crime during the same period. Sensation and deviation as news value criteria appear, in this respect, to be more present in print than in interacted news.

As for the large difference in negativity between print and online disseminated news—and thus between digital opinion leaders and journalists—this result calls for more research in order to confirm and further develop this finding. For example, is the result significant only in the main interacted stories and main print stories in tabloids, or is it a general difference between media distributed and audience circulated news content?

Conclusions and discussion

Prior to outlining some discussion themes that we find important, we will explicitly answer our research questions.

First, the interpretation of the results about the digital opinion leaders must be that they have more time, since they live alone to a larger extent. They are also more interested in social issues since they demonstrate a greater political interest than others. In addition, they are younger and more digitally aware than others, in all respects.

Second, the character of the most interacted news in social media has not changed very much from 2014 to 2015, with one exception: the news stories have become more positive. As a topic, politics has decreased its share of the most interacted news, and the explanation is most likely that in 2014 Sweden had two elections, and none in 2015. However, hard news still dominated in 2015 as the most interacted news online.

Third, the main difference between most interacted news in social media and the front-page main story in a print tabloid is the topic and level of negativity. The printed main story was much more negative in both form and topic.

If we now turn the broader issues, traditional news value criteria seem to be as valid in the most interacted news in social media as it is in the traditional media, even though the news is more positive. One explanation for the general conformity is, of course, that the original sources are mainly traditional news companies, and this is also true of the most spread viral sites. The spreadable media criteria that we tried to use does not serve as well as traditional news criteria in the analysis. News seems to be subject to laws other than media content in general. One explanation as to why traditional news value criteria also appears to govern spreadable content might be that we are still at the beginning of a viral news era, and it is difficult for anyone to move beyond what is commonly expected, that is, what a news item is and how it should be presented.

However, the development of specific viral sites might say something interesting about the future. Many of the traditional media companies have developed viral sites, or have been influenced by viral sites, in order to become easily spreadable in social media (cf. Jenkins et al., 2013). Much of the material on the viral sites is not news. It is also not original material, but has been taken from YouTube or other sources. It is therefore inexpensive (cf. Bakker, 2012). In the news organisation it is simple to change even ‘real’ news stories or headlines in order to increase the number of clicks (cf. Tandoc Jr, 2014). Therefore one question for the future is whether the spreadable content will be news or primarily other material, independent of the original source. Will the content be important in social terms or merely amusing?

At the same time as the viral content—not necessarily news—gains ground, Facebook invites news organisations to host their content via instant articles. Some commentators see this as highly dangerous, others as the only way for the media to survive (e.g., Filloux, 2015). Will the distribution and spread of news increase, or will other types of content replace news in social media? How will nuanced, long-form, well-researched news stories hold up in the new media landscape? Will we see more intricate discussions of racism or more cute kittens? There will certainly be some kind of mix, and one does not have to rule out the other, but the balance is not self-evident and the media consumption might be even more individual. Only the future can tell.

Bibliographical References

Bakker, P. (2012). Aggregation, content farms and Huffinization. Journalism Practice, 6(5–6), 627–637.

Bro, P., & Wallberg, F. (2014). Digital gatekeeping. Digital Journalism, 2(3), 446–454.

Brüggeman, M., Engesser, S., Büchel, F., Humprecht, E., & Castro, L. (2014). Hallin and Mancini revisited: Four empirical types of Western media system. Journal of Communication, 64(6), 1037–1065.

Carey, J., & Elton, M. C. J. (2010). When media are new. Understanding the dynamics of new media adoption and use. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press and the University of Michigan Library. [ Links ]

Costera Meijer, I., & Groot Kormelink, T. (2014). Checking, sharing, clicking and linking. Digital Journalism. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2014.937149

Dubois, E., & Gaffney, D. (2014). The multiple facets of influence: Identifying political influential and opinion leaders on Twitter. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(10), 1260–1277.

Erdelez, S., & Yadamsuren, B. (2011). Online news reading behavior: From habitual reading to stumbling upon news. Proceedings of the ASIST Annual Meeting, 48(1): 1-10. [ Links ] DOI: 10.1002/meet.2011.14504801139

Filloux, F. (2015). Jumping in bed with Facebook: Smart or desperate? Retrieved from www.mondaynote.com/2015/04/06

Ghersetti, M. (2012). Journalistikens nyhetsvärdering [News values in journalism]. In L. Nord & J. Strömbäck (Eds.), Medierna och demokratin [Media and democracy], pp. 205-232. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Gottfried, J., Guskin, E., Kiley, J., & Mitchell, A. (2013). The role of news on Facebook: Common yet incidental. Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2013/10/24/the-role-of-news-on-facebook/

Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hermida, A., Fletcher, F., Korell, D., & Logan, D. (2012). Share, like, recommend. Journalism Studies, 13(5–6), 815–824.

Jenkins, H., Ford, S., & Green, J. (2013). Spreadable media. Creating value and meaning in a networked culture. New York: New York University. [ Links ]

Kaiser, C., Kröckel, J., & Bodendorf, F. (2013). Simulating the spread of opinions in online social networks when targeting opinion leaders. Information Systems and e-Business Management, 11(4), 597–621.

Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1955). Personal influence. The part played by people in the flow of mass communication. Glencoe: Free Press. [ Links ]

KIA Index (2015). Retreived from www.kia-index.se /2015/06/01

Kim, Y., Chen, H.-T., & de Zúniga, H. G. (2013). Stumbling upon news on the Internet: Effects of incidental news exposure and relative entertainment use on political engagement. Computers in Human Behaviour, 29, 2607–2614.

Lee, C. S., & Ma, L. (2011). News sharing in social media: The effect of gratifications and prior experience computers. Human Behaviour, 28, 331–339.

Liljemalm, A. (2014). Sebbe – mest last genom tiderna. [Sebbe – most read ever]. Retreived from www.gp.se 2014/01/25.

Ma, L., Lee, C. S., & Goh, D. H-l. (2014). Understanding news sharing in social media. An explanation from the diffusion of innovation theory. Online Information Review, 38(5), 598–615.

Nordicom (2016). The Media Barometer 2015. Retrieved from www.nordicom.gu.se/en/media-trends/media-barometer 2016/11/06.

Neuberger, C. (2014). The journalistic quality of Internet formats and services. Digital Journalism, 2(3), 419–433.

Ritzer, G., Dean, P., & Jurgensen, N. (2012). The coming age of the prosumer. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(4), 379–398.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusions of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press.

Shi, M., & Wojnicki, A. C. (2014). Money talks… to online opinion leaders: What motivates opinion leaders to make social-networks referrals. Journal of Advertising Research, 54(1), 81–92.

Shoemaker, P. J., & Vos, T. (2009). Gatekeeping theory. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Skäringer, M. (2014). Det sista vi behöver är ännu ett diettips. [We don’t need another diet advice]. Retrieved from www.aftonbladet.se 2014/03/07.

Tandoc Jr, E. C. (2014). Journalism is twerking? How web analytics is changing the process of gatekeeping. New Media and Society, 16(4), 449–575.

Vernersdotter, F. (2014). Den nationella SOM-undersökningen 2013 [The national SOM Survey 2013]. In A. Bergström & H. Oscarsson (Eds.), Mittfåra och marginal [Mainstream and mariginal], pp. 531-559. Göteborg: SOM-institutet.

Wadbring, I., & Ödmark, S. (2014). Delad glädje är dubbel glädje? En studie om nyhetsdelning i sociala medier [Shared joy, double joy? A study about news sharing in social media]. Sundsvall: Demicom, Mittuniversitetet.

Weeks, B. E., & Holbert, R. L. (2013). Predicting dissemination of news content in social media: A focus on reception, friending, and partisanship. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 90(2), 212–232.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Carl-Olov and Jenz Hamrins stiftelse, a private foundation for media research tied to the Herenco Group, as well as by the Journalists’ trade union.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Coding definitions

All questions are answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ if nothing else is written. The comments under each variable were used in the coding process as definition and guidance for the coder.

Proximity in time: Has the news story been published within a week of the time of sharing?

Comment: Refers to the stated first time and date of publishing of the news item.

Proximity in space: Is the news story mainly about Sweden or the Swedes?

Comment: If the news story takes place in Sweden or features Swedes it should be considered a ‘yes’.år ej﷽﷽﷽﷽﷽: Svenskar i Sverige, svenskar utomlands, ickesvenskar i Sverige, ickesvenskar utomlands

Sensation and deviation—unknown or unexpected: Can the news story be considered unexpected, rare or previously unknown by the public?

Comment: The threshold is low for what is considered unexpected or previously unknown by the public. Even if the news story covers a general topic, the specific angle would likely be assumed to be previously unknown by at least a section of the public.

Sensation and deviation—valence: Is the news story mostly depicted in a negative or a positive manner?

- Positive

- Negative

- Neutral or dependent on the opinion of the consumer

Comment: This variable concerns the headline and the main angle of the story. Even though the ideology of the consumer naturally affects all interpretations of news, the story itself is generally phrased in either a positive or a negative way.

Elite centring: Is the main character of the news story part of a political, economical, cultural, academic or sporting elite?

Comment: Well-known names such as TV-personalities are considered cultural elites. Company representatives are non-elite as long as they are not the CEO. It is not enough to be quoted as an ‘expert’ to be considered elite. Well-known sports figures are considered elite even if they are retired from their active careers.

Simplification: How many sources of different perspectives are featured in the news story?

- One

- Two

- More than two

Comment: By sources we mean people referred to in quotes. The quoted sources need to have clearly opposite or diversified perspectives from each other in order to be considered different.

Shared experience—emotions: Is the news story designed to move the consumer, through, for example, the use of nostalgia, sentimentality or an uplifting message?

Comment: This is particular to the sense of being moved or touched, not just evoking emotions in general. This might be through the use of sentimental quotes or descriptions of heartfelt scenes.

Shared experience—personal address: Does the news story address the consumer in an including and/or personal way with an assumed intent of being relatable?

Comment: This can be done, for example, by writing in ‘we’ form or by describing everyday scenes with the purpose of recognition.

Humouristic/parodic: Does the news story have elements of humour or parody?

Comment: There has to be an apparent humorous intent behind it to be coded ‘yes’.

Incomplete story: Is there a direct call for interaction due to the incomplete nature of the story?

Comment: Applies if the consumer is prompted to contribute to the development of the story due to its incomplete nature.

Mysterious story: Are there elements of mystique regarding the news story?

Comment: By ‘mystique’ we mean clearly stated unknown facts that are vital to the origin of the story, something that is connected to the paranormal or just a riddle/puzzling/unexplained for both the producer and the consumer of the story. Psychological questions (such as, Why did he do it?, in connection with crimes) are not included because the purpose of these variables is the mystery surrounding the news item itself (such as, Is this video of a UFO real?).

Controversial story: Is the news story about a controversial topic, does it involve a controversial person, or could it in any other way cause a debate?

Comment: The definition of controversial here is something or someone that can cause opposing opinions and/or outrage.

Rumour-based story: Is the news story based on unconfirmed information?

Comment: To be coded ‘yes’, it has to be clearly stated in the news story that it is unconfirmed.

Topic:

- Politics/economy

- Culture/entertainment

- Accidents/crime

- Sports

- Lifestyle/health

- Other