Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.12 no.1 Lisboa mar. 2018

Predictors of Mistrust: Towards Basic Characteristics of Czech Mistrusting News Media Audiences

Jaromír Volek*, Marína Urbániková**

* Masaryk University, Czech Republic

** Masaryk University, Czech Republic

ABSTRACT

This study examines audiences mistrusting in Czech journalists. It is based on two representative survey of Czech adult population. Data were subjected to descriptive, correlation and regression analysis. Analysis reveals that public trust in journalists declined by a third between 2004 and 2016. The major contribution of study is the finding that the mistrust in Czech journalists has multi-dimensional structure and supports main parts of the regression model. The regression analysis revealed five main predictors of mistrust among mistrusting audiences - age (the youngest respondents), the lowest economic background, left-wing orientation, perceived negative ethical image of journalists and perceived negative professional image of journalists. The analysis suggests that a significant part of the Czech public is returning to the old communist regime perception of journalists as representatives of establishment who do not represent its interests.

Keywords: Czech journalists; mistrusting audiences; public trust, regression analysis, survey

Having the trust of the audiences is of fundamental importance for media and journalists. Trust constitutes a key working tool of journalists which help them to make the world more intelligible for their audience, to translate historical, political, and cultural change into controllable concepts, and they create a sense of ontological security for ordinary citizens. Public trust in news media and in journalists constitutes a key precondition for the accomplishment of the journalistic role. It allows the audience to make sense of the world without checking each piece of information coming from the news media. In this sense, journalists derive their authority from their ability to create a credible symbolic environment in an unreliable social world. Simultaneously, to trust in the news media means to trust in other social actors; it is a dialectical relationship which is a condition for the stability of the whole socio-political system. Journalists serve as an intermediary between the government and the people, which provide with information and open forum for the views of citizens.

However, if a big part of the society loses a certain critical level of their trust in these creators of ontological security, the stability of the social system is endangered. The lack of trust can therefore be a potential threat for democracy. And finally, media and journalists do not only depend on trust of their audiences, they also play an important role in the process of building trust in other parts of society. Trust is a basis for social cohesion and social order (Gellner, 1990) and it is required as an input condition for functioning of social system (Luhmann, 1990); without trust, the stability of the social system is at risk.

In the European Union, trust in the media has been falling systematically in the past eight years in both the old EU countries and the new ones (Eurobarometer, 2016). However, the fall in trust in the latter is more distinctive, exceeding 10%. While in 2007, 61% of respondents from both the old and new member states tended to trust the media, by 2015, this number decreased to 54% in case of respondents from the old member states and 48% in case of respondents from the new member states.

This suggests that in the post-communist countries, public trust is more fragile in comparison with the stable Western democracies. This is especially true for the young Czech liberal democracy. One of the most important indicators of its weakening is the gradual loss of trustworthiness of Czech journalists.

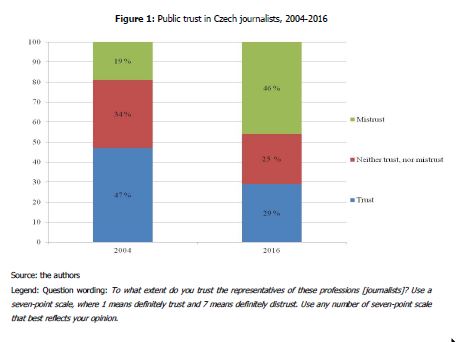

The level of Czech public trust in journalists declined significantly between 2004 and 2016. The share of trusting respondents decreased by a third (from 47% to 29%), and the share of mistrusting respondents increased significantly from 19% to 46% (figure 1).

These findings are in line with previous studies affirming the increasingly sceptical attitude of the public towards the journalists in many western countries (e.g. Tsfati & Peri, 2006; Gronke & Cook, 2007; Lee, 2010; Muller, 2013; Gallup, 2016).

The Rise and Fall of Public Trust in Czech media

According to cultural theories, trust in people and in institutions is a product of accumulated historical experiences (Sztompka, 2000), and it is intergenerationally transmitted and deeply embedded in society (Mishler & Rose, 2005). The question of public trust in media and journalists in the Czech Republic has to be therefore considered in a broader context of its history and the transformation of the society after the fall of the totalitarian regime (also known under the catchphrase “real socialism”) in 1989.

The previous regime as well as the transformation process of so-called post-communist societies are thought to caused a widespread erosion of trust in the Central and Eastern European countries, including the Czech Republic (see, e.g., Mierina, 2011). According to Sztompka (2000), communist societies developed a "bloc culture" with various traits and characteristics leading to the decay of trust, e.g. the distinction between public sphere (domain of the bad) and private sphere (domain of the good) going hand in hand with the double standard of truth (official and private), or autocratic style of politics with arbitrary policies and unclear criteria of political decisions. Trusting the state and its political institutions, including media and journalists, was seen as naive and stupid, and, on the other hand, trying to beat the system and outwit the authorities was widely recognized as virtue. Therefore, as put by Rose (1994: 18), distrust can be considered as "a pervasive legacy of communist rule''.

The fall of the communist regime and the democratic replacement of the old and distrusted regime brought a wave of national unity and solidarity, as well as revival of public trust. This was only temporary, as the pains of transformation process with its radical political, economic, and societal changes led to the "post-revolutionary malaise'' or "the morning after syndrome'' (Sztompka, 1992), and with that to a profound collapse of trust (Sztompka, 2000). Rigid social controls were released, old norms have fallen down, and new ones have not yet been developed, and emergence of new life chances generated brutal competition with unclear rules (Sztompka, 2000). However, the consolidation of political democracy, economic growth and the inclusion into Western alliances, together with generational turnover, initiated gradual revival of trust (ibid.).

Naturally, Czech media and journalists did not stand unaffected by this historical development. After the World War II, the Czech journalistic field was formed under the direct influence of the so-called Soviet theory of journalism, which saw journalism primarily as propaganda activity aimed at educating citizens to be loyal to the communist establishment and the Communist Party as the leading force, which has the right "when journalist activity does not correspond to its demands, to strip him of the right to speak on its behalf, or may choose other means to influence him" (Tepljuk, 1989). Although there are no data on public trust in journalists from the pre-1989 period, it can be assumed that especially in the last decade before the transition it was on a low level. The Czech public, for instance, projected this kind of mistrust into a saying popular at the end of 1980s: ‘Czech TV lies like Rudé právo prints’.

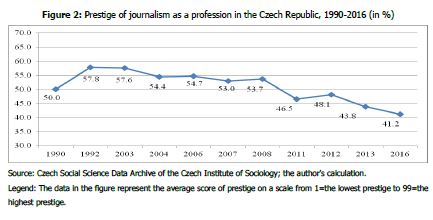

After 1989, public trust in journalists and media has been at least partially restored, only to experience a decline starting after the outbreak of the economic crisis in 2008. As a proxy indicator for missing data on public trust before 1995, a continual measurement of prestige of journalistic profession among the Czech public starting in 1990 can be used. It shows a significant increase in perceived prestige in the early years shortly after the collapse of old regime until the arrival of the economic crisis (figure 2).

Public Trust in News Media and Journalists: Literature Review

A number of studies affirm the increasingly sceptical attitude of the public to the until recently accepted journalistic privilege to explicate social reality (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2001). This process of weakening trust in the media concerns different media systems with different intensity. For instance, Gronke and Cook (2007) show that, between 1973 and 2000, the trust of the public in the US media sank more than trust in any other observed professions. According to a recent Gallup poll (2016), trust and confidence in the media among American public has fallen to the lowest point in the poll’s 44-year history, with only 32% saying they have a great deal or fair amount of trust in the media. Muller (2013) points out that the biggest slump in trust can be detected in the countries which, according to the typology of Hallin and Mancini (2004), belong to the North Atlantic/liberal media system. In contrast, quite stable trust prevails in the countries with Mediterranean/polarized pluralistic models and in the countries with North and Central Europe/democratic-corporatist models.

The research on the public trust in the journalistic field monitors two main topics: a) analysis of trust in media institutions, usually conducted through a comparison of individual media types, and b) less frequent research on the trust in journalists as a socio-professional group.

Concerning the main characteristics of mistrusting audiences, according to the previous studies, trust in news organizations, journalists and the news does not map particularly well onto socio-demographic variables (Jackob, 2010; Newman, Fletcher, Levy & Nielsen, 2016) and the findings are often inconsistent in this respect (Tsfati & Ariely, 2014). This applies especially to age: while older research suggested that young people were less likely to trust media and journalists (Westley & Severin, 1964; Carter & Greenberg, 1965; Greenberg, 1966), newer studies from various countries come to an exactly opposite conclusion (Newman, Fletcher, Levy & Nielsen, 2016; Gallup, 2016).

Among the most frequently tested characteristics of mistrusting audience are values and ideological attitudes (Gunther, 1992; Hoffner & Rehkoff, 2011; Lee 2005; Lee, 2010). A number of studies pose the question of whether, and to what extent, are journalists’ political stances related to public trust in media and journalists (Dennis, 1997; Domke et al., 1999; Farnsworth & Lichter, 2011). Previous research indicate that the stronger the group identification or the stronger the ideological stand of media consumers, the higher their mistrust in specific media as the bearers of opposing attitudes. This kind of mistrust is rising especially among individuals advocating extreme ideologically structured mind-sets – strong conservatives, socialists, and liberals are distinctively less trustful (Glynn & Huge, 2014; Lee, 2005; Lee, 2010). This mistrust is often further incited by criticisms of the media expressed by representatives of political parties in order to spread mistrust among their supporters/followers.

Another frequent research topic is related to the extent of consumption of specific media types and attempts to answer the question whether trust rises with the amount of media consumption (Johnson & Kaye, 1998; Kiousis, 2001). Most studies confirm the assumption that the more audiences trust mainstream media, the more of their news coverage they consume, and vice versa (Tsfati & Cappella, 2003). The theory of selective exposure ( Sullivan, 2009 ; Bryant & Davies, 2009 ; Smith, Fabrigar & Norris, 2008) is effective here; it presumes that media consumers favour the sources that they trust as they support their political attitudes, simultaneously fuelling mistrust in the media that advocate other values. The role of this selectivity has been tested and confirmed on all employed socio-demographic levels. It appears that those who despise journalists and mainstream media tend to look for alternative sources. In reverse, those who trust media are more likely to trust them the following day and the following year (Tsfati, 2003). The audiences who are generally mistrustful consume mainstream media less (Tsfati & Cappella, 2003).

Methodology, Research models and Hypotheses

Examining the structure of mistrusting Czech audiences, the following main research question was posed:

RQ1. What are the selected predictors of mistrust in Czech journalists among audiences?

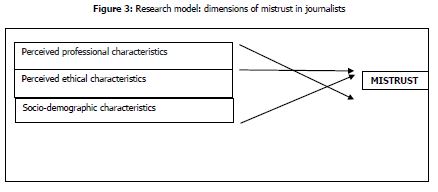

The research model (figure 3) defines three dimensions determining mistrust towards journalists – “socio-demographic” and “evaluative”. The first includes the following indicators (a) age, (b) gender, (c) education, (d) household income, (e) media consumption, (f) political orientation of mistrusting audiences. The second and third dimension consists of positive or negative evaluation of journalist´s image including: (a) perceived personality and professional characteristics (useful/ useless, respectable/sensational, educated/ uneducated, brave/cowardice), (b) ethical integrity indicators (moral/ immoral, independent/ dependent, incorruptible/ corruptible, responsible/ irresponsible). Our model tests ability these variables to predict the level of audience mistrust in journalists. The model uses mistrust as the dependent variable (DV).

The first two professional/ethical image dimensions correspond generally with Haller’s (1992) classification along various value structures and the multi-layer system of responsibility introduced by Pürer (1992). He defines journalists´ ethical (professional) responsibility to the audience as a common result of the audience's demands and the pressure that creates professional rules. In our study, we will therefore assume the existence of a strong tradition of virtue-based ethics among public which states that the journalist should have a diligent, reliable, honest, and trustworthy character and act with discernment.

Thus we understand the public image of journalists as a result of the perception and evaluation of their professional and ethical prerequisites which not only to comply with the professional codes, but also with the general moral expectations of the public. These expectations take place not only in the professional sphere, but they are also influenced by the wider historical and social context, respectively the cultural and historical memory of the public which affected the perception of general importance of journalism in a society (Lauk, Harro-Loit, 2017).

Based on the above mentioned previous studies, the hypotheses related to the predictors of mistrust were set in the following way:

H1. There is a positive association between audiences with lowest economic background (head of household income) and their mistrust in journalist.

H2. There is a positive association between audience with left-wing political orientation and their mistrust in journalists.

H3. There is a positive association between audience with the lowest formal education and their mistrust in journalists.

H4. There is a positive association between age (youngest audiences 18-29) and their mistrust in journalists.

H5 There is a positive association between mistrust in journalists and their perceived negative professional image.

Association of the professional image of Czech journalists with following semantic characteristics was measured on seven point scale. Semantic indicators represented following dichotomies: sensationalistic/respectable, uneducated/educated, cowardly/courageous, useless/ useful.

H6. There is a positive association between mistrust in journalists and their perceived negative ethical image.

Association of the image of Czech journalists with following semantic characteristics was measured on seven point scale. Semantic indicators represented following dichotomies: corruptible/incorruptible, dependent/independent, immoral/ moral, irresponsible/responsible,).

The study is based on a quantitative comparative analysis of data from two surveys designed by the authors as a part of research project (name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process) . The surveys were conducted with a twelve-year interval, the first data collection took place in February and March of 2004, the other in February and March of 2016. Both data sets are representative for the Czech 18+ population. The sampling was based on socio-demographic quota selection (gender, education, age, region, settlement size, socio-economic position) reflecting the structure of the Czech population. In all, 1084 respondents were surveyed in 2004, and 1236 were surveyed in 2016. The data were collected by social research companies according to the instructions of the authors; in both cases, the CAPI data collection strategy was used. Data were subjected to descriptive, correlation and standard multiple regression analysis. Data for test of the last two hypotheses were measured by using a 7-point scale which ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). The data were analysed with the aid of Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.

Finding s

Com parison of the basic characteristics of mistrusting audiences (2004 vs. 2016)

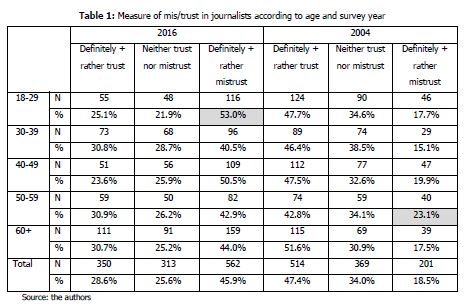

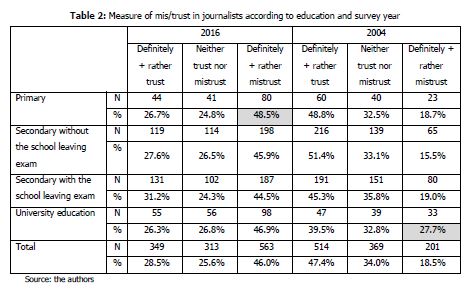

Changes in the age structure of mistrust audiences are particularly significant (Table 1). One fifth (18%) of the distrustful in the youngest target group in 2004 increased to more than one half. In other words, we can say that the distrustful audience has become younger in the last decade. Simultaneously, they no longer belong to the formally best educated respondents, who should exhibit a higher level of critical media literacy (Table 2). On the contrary, the mistrust grew most distinctively with the consumers with the lowest formal education – from 19% to 49%.

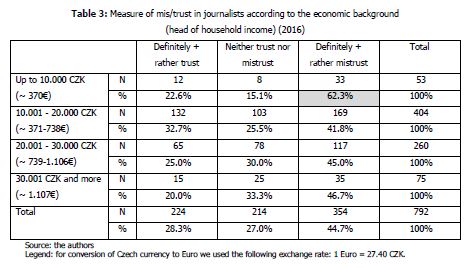

Apart from the above-stated characteristics, a higher level of mistrust is also associated with the lower economic background respondents (Table 3).

This basic socio-demographic description of the mistrusting audiences indicates that the journalists working for "big media" are mistrusted by those respondents who, in one way or another, appear on the margins of society. These findings appear throughout our study and hint that mainstream media and mainstream media journalists are more accepted by those who are socially and economically quite successful. This finding corresponds with the last described characteristics – political orientation of mistrusting audiences.

This type of values preferences of the media and journalists and the measure of their agreement with the preferences of potential consumers, is a well-researched topic (Dennis, 1997; Farnsworth & Lichter, 2011; Gunther, 1992; Hoffner & Rehkoff, 2011; Lee, 2005; Lee, 2010).

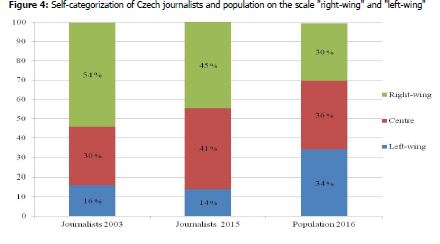

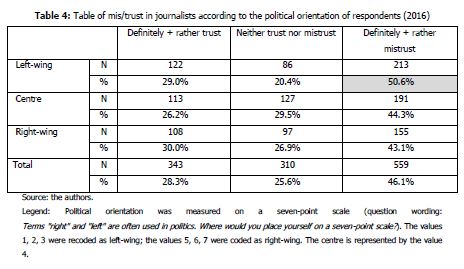

Research data from the Czech Republic shows a value asymmetry between public and journalists – left-wing respondents prevail in the adult population, but middle-right orientation prevails among journalists (figure 4). In this perspective there is no surprising that the left-wing respondents will be most distrustful to journalists (Table 4).

Although the comparison of the newest political preferences of journalists (2016) with the data from 2004 shows that this value disproportion has been diminishing in the last decade, the stated asymmetry remains. Left-wing consumers perceive it as an expression of insufficient representation of their interests, and their mistrust in journalists is growing. It seems that while Czech journalists have been moving from right-wing to centre positions in the last decade, a minority of the society has been heading to the left. Both trends reinforce the edges of the political spectrum.

In line with the studies outlined above, mistrust i journalists is particularly strong among respondents with extreme political attitudes – left-wing. The more identified the media consumers are with the extreme positions, the more probable their increase of mistrust in the mainstream media (Glynn & Huge, 2014; Lee, 2005; Lee, 2010). As Table 5 shows, the strongest mistrust was reported by the extreme left-wing respondents, whereas the mistrust of the extreme right-wing consumers stays below the average of the whole population. This may be a reflection of the right-wing liberal political preferences widely held by Czech journalists.

Legend: From a seven-point scale measuring political orientation, the values 1 (left-wing position) and 7 (right-wing position) were selected as extremes.

Predictors of mistrust in journalists: regression model

To identify predictors of mistrust in journalists we started with principal component analysis (PCA) using a direct oblimin rotation of the scale items reflecting above mentioned “socio-demographic” and “image- evaluative” variables. Prior to performing PCA, the suitability of the data for factor analysis was assessed. Inspection of the correlation matrix revealed the presence of many coefficients of 0.3 and above. The Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin value was 0.661. This exceeds the recommended value of 0.60. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity reached statistical significance ( p = 0.000), supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix. Initial PCA revealed the presence of four factors, with eigen values exceeding 1, explaining 63.7% of the variance cumulatively. During multiple iterations of PCA, 2 items required elimination (gender, media consumption) because it failed to meet the minimum criterion of having a primary factor loading of at least 1 and cross-loaded highly on more than one factor. As a result, these items were dropped.

A sTable 2-factor (professional image factor, ethical integrity image factor) and 8-item solution emerged. The Cronbach’s alpha test was used to test the internal consistency of the scale items (Hair et al. 1998). Results revealed sufficiently high internal consistency for all scales, ranging from 0.776 to 0.937.

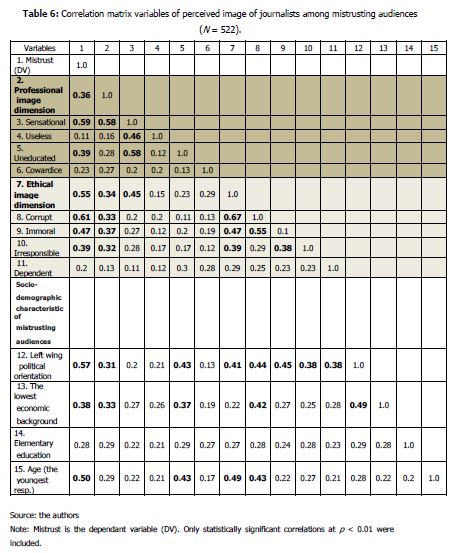

Table 6 shows that the scales were tested for independence using Pearson’s correlation which were significant at p < 0.01 levels. In the first “professional dimension (construct)” we see the strongest correlations with sensationalisms ( r = 0.580, p < 0.01) and positive relationship between perceived uselessness and sensationalism of Czech journalists ( r = 0.460, p < 0.01). Sensationalism has also the strongest correlation with mistrust ( r = 0.590, p < 0.01). Strongly correlated was perception of Czech journalists as an uneducated by the youngest respondents ( r = 0.50, p < 0.01) with the lowest economic background ( r = 0.370, p < 0.01) and left wing political orientation ( r = 0.430, p < 0.01). This suggests that especially the youngest mistrusting audiences accentuate generally (low) professional quality of Czech journalists output and its marginal role for society.

The second “ ethical dimension (construct)” dominates positive relationship with perceived corruptibility of Czech journalists ( r = 0.67, p < 0.01) which has the strongest relationship with mistrust among all others variables. It is strongly correlated with immorality of journalists ( r = 0.47, p < 0.01) and their irresponsibility ( r = 0.39, p < 0.01). This suggests that mistrust in journalists may be influenced especially by their perception as self-centred news brokers (Hardt, 1990). This interpretation also supports a relatively strong correlation between irresponsibility and immorality ( r = 0.38, p < 0.01). This ethical criticism is strongly correlated with youngest ( r = 0.49, p < 0.01), and left wing political orientation ( r = 0.410, p < 0.01).

The correlation analysis suggests existence of two relatively independent dimensions (constructs) which determine mistrust to journalists. Preliminary analyses were performed to ensure no violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity and homoscedasticity (Hair et al. 1998). Intercorrelations among scales did not exceed 0.70, and therefore, the independence of the scales was considered adequate for this study. According to intensity relationship between two dimensions seems that stronger role plays second one - “ethical dimension”.

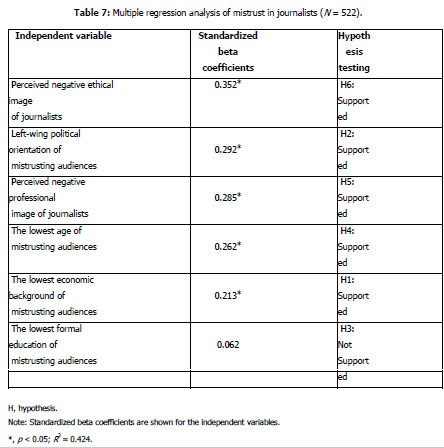

Multiple regression analysis was used to test if the five independent variables: age

(the youngest), the lowest economic background, elementary education, left wing political orientation of mistrusting audiences, negative professional image dimension, negative ethic image dimension significantly predicted the dependent variable – mistrust in journalists.

The results of the multiple regression analysis in Table 7 reveals that H1: economic background of mistrusting audiences (21.3%), H2: left-wing political orientation of mistrusting audiences (29.2%), H4: perceived professional image (28.5%), H5: perceived ethical dimension (35.2%) jointly explains 42.4% of the variance of mistrust in journalists. The variable education of audiences (H3) offered no significant relationship with mistrust in journalists.

Discussion of the findings

In the last two decades, the trust in media and journalists is on the decline in most developed post-industrial societies. There is more than one reason for the current situation, and Czech journalists share some of these reasons with journalistic communities of highly developed media landscapes.

Our analysis supports hypotheses 1, 2, 4 that the mistrust increases with the lowest economic background, left-wing orientation and the lowest age of the mistrusting audiences. It is in accordance with newer studies from various countries (e.g. Newman, Fletcher, Levy & Nielsen, 2016; Gallup, 2016), which show a strong mistrust with the youngest and middle generation.

The analysis supports hypotheses 5 and 6. The study has shown that the most prominent predictor of mistrust towards journalists is their “ethical image” associated especially with their tendency to corruption. An important role here is played by other ethical principles of journalistic work that are related to the multi-layer system of responsibility introduced by Pürer (1992). This more or less intuitive perception of journalists by the optics of the ethical level of their work is reinforced especially by left-wing orientation and the lowest economic background of the youngest mistrusting respondents. They see as the third strongest predictor of mistrust the “professional image” of journalists, which is especially associated with their tabloid style and low level of professional education.

As the descriptive analysis showed, the highest level of mistrust is reported by respondents with the lowest economic background. On the contrary, we see the highest trust in the middle class respondents. It indicates that Czech journalists find their reference group in members of this class, belonging to the middle and oldest generations. It is likely that they are individuals who have a higher share of power. If that would be the case, assumption that part of the lack of trust in journalists is the result of their identification with the establishment, is likely to be considered.

This process of decline of trust in journalists has a number of causes and is part of wider global socio-technological trends that affect both media market and the journalistic performance itself. One of them is current trend of the fragmentation of audiences, who no longer respect the sacred space-time of the prime time news coverage programmes. They are not willing to accommodate their leisure time activities to firmly set broadcasting schedules, as their parents and grandparents were. This process also includes a gradual decrease in journalists’ authority, which has traditionally been grounded on the authority of the media they worked for. Instead, they are confronted with the authority of amateur journalists operating in cyberspace. The image of professional journalists is gradually being contaminated by the ethical and professional "standards" of amateur journalists operating on the web who have no respect for professional rules. It is a symptom of disintegration of the more traditional, firmly fixed social position of journalists, who had lived their professional lives by strictly defined professional rules. The weakening of this social position creates a situation in which journalism is increasingly open to deprofessionalization, which media consumers criticise. (Singer, 2003; Witschge & Nygren, 2009).

It seems that this increasing mistrust is also related to broader changes in the current image of journalists and journalism, an image which is perceived by the part of public as too distant from their actual problems, regardless of their political preferences. The ideal-typical film or fictional/literary image of journalists as "ardent reporters" – people who protect the public from an inhumane regime – has begun to fall apart and its outlines have blurred. (reference deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process) . This in turn weakens an important component in the ontological security of media consumers, who no longer reward journalists for their calculable conduct in the role of guardians of their interests. The dissolution of this traditional image of journalists entails the deterioration of their perceived trustworthiness.

Apart from the outlined global socio-technological determinants of increasing mistrust, there are some local socio-economic or political determinants in each national media system. In this perspective, three time-structured types of audience mistrust can be distinguished: a) short-term , which represents only a partial disruption of trust – it is related to individual scandals and journalists’ failures, b) middle-term , which exceeds several-month intervals and can be triggered by journalistic practice partaking in some adverse social processes. However, the most dangerous, from the media point of view, is c) long-term , usually gradually increasing mistrust.

It can be assumed that Czech media and Czech media journalists are being confronted with the type of chronic mistrust that has reached the third phase. There seems to be one more general cause: a growing distance between the media and their audiences, related to the fact that a substantial number of Czech journalists sacrificed professional rules in order to support the new regime, to which they offered not only their careers but also their values. Nevertheless, their identification with the building of plural democracy was gradually confronted with the increasing discontentment of the majority of the population, critically reacting to broken promises of economic a politic transformation after collapse of old regime. There was a delayed increase of mistrust on the part of media consumers who, in the first post-1989 decade, perceived journalists as being on their side in the hope of better future. This hopeful trust was markedly disrupted by the economic crisis.

Thus, the significant decline of public trust in Czech journalists can have far-reaching socio-political consequences, as the disappointed audiences mistrusting of journalists may tend to be more susceptible to other sources lacking professional standards and principles of mainstream journalism. This poses an existential threat to democracy with informed citizenry as its essential element, since confused, uninformed, misinformed, or disinformed populace is unable to make sound decisions.

This process has its historical causes, which are related to the already mentioned effort of Czech journalists to support, after the collapse of the old regime, the building of a new organization of society based primarily on the neoliberal right-wing ideology that most journalists took for themselves.

The long-term inclination of a larger part of Czech journalists to the center and right wing values speaks for this interpretation. It seems that the above mentioned value asymmetry between political preferences of journalists and population, has started to ‘backlash’ at the journalists in the form of more markedly declared mistrust. This comes especially from the left-wing part of the audience with low economic background. This higher degree of mistrust of this part of audience can be interpreted as a consequence of the sense of asymmetric and insufficient representation of its values and interests.

Generally speaking, a substantial part of the public seems to have an impression that journalists do not keep the symbolic social contract they have concluded with them. However, it can be assumed that this decline in trust cannot be related only to journalistic professional behaviour. It is probable that the crisis of trust in journalistic profession is part of a more general process of growing mistrust in public institutions (Norris, 1999). This process has been boosted by the economic crisis that has plagued the Czech society after 2008 and reinforced the feeling of unfulfilled expectations that linked a substantial part of the population to the new regime. In this sense, Czech media consumers behave in a manner similar to some of their foreign counterparts (Glynn & Huge, 2014; Lee, 2005; Lee, 2010).

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to analyze the decline of public trust in Czech journalists in the time span of twelve years, and to describe the structure and main characteristics of the mistrusting audiences. As expected, the level of public trust in journalists declined significantly between 2004 and 2016 (the percentage of mistrusting public increased from 19% to 46%). This means that the Czech Republic as a central European country with a post-communist media model is no exception from the trend of a rising public mistrust in media and journalists present in the most developed Euro-American countries.

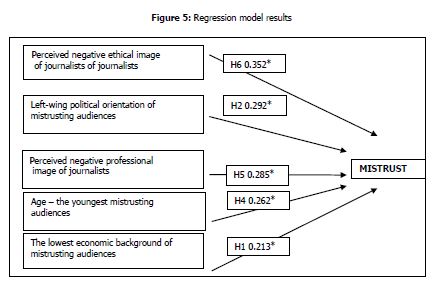

The major contribution of this study is the finding that the mistrust in Czech journalists has its own local socio-political particularities. Using survey data, we employed regression modelling to test six research hypotheses. The results from the empirical study of the 522 mistrusting respondents found support for hypotheses 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6 (figure 5)

Multiple regression analysis confirms multi-dimensional structure of the public mistrust in Czech journalists. It is composed in particular of the following five variables: age (the youngest respondents, the lowest economic background, left-wing orientation, respectively constructs/factors - perceived negative ethical image of journalists and perceived negative professional image of journalists. These variables are significant predictors of mistrust in the Czech journalists.

References

Bryant, J., & Davies, J. (2008). Selective Exposure. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Communication (pp. 4544-4550). Malden, Oxford, Carlton: Blackwell Publishing.

Carter, R.F., & Greenberg, B.S. (1965). Newspapers or Television: Which Do You Believe? Journalism Quarterly, 42, 29-34. [ Links ]

CVVM. (2015). Důvěra některým institucím veřejného života v říjnu 2015. (Trust in Selected Public Institutions in October 2015) Retrieved from http://cvvm.soc.cas.cz/media/com_form2content/documents/c1/a7447/f3/po151119.pdf.

Czech Social Science Data Archive of the Czech Institute of Sociology (Data file). Available from http://nesstar.soc.cas.cz/webview/

Dennis, E. E. (1997). How ʽliberalʼ are the media anyway: The continual conflict of professionalism and partisanship. Journal of Press/Politics, 2 (4), 115-119. [ Links ]

Domke, D., Watts, M. D., Shah, D. V., & Fan, D. P. (1999). The politics of conservative elites and the liberal media argument. Journal of Communication, 49 (4), 35-58. [ Links ]

Eurobarometer. (2016). Public Opinion: Trust in Institutions (Data file) . Available from http://ec.europa.eu/COMMFrontOffice/PublicOpinion/index.cfm/Chart/index

Farnsworth, S. J., & Lichter, S. R. (2011). The contemporary presidency. The return of the honeymoon: Television news coverage of new presidents, 1981-2009. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 41 (3), 590-603. [ Links ]

Gallup. (2016). Confidence in Mass Media. Retrieved from: http://www.gallup.com/file/poll/195575/Confidence_in_Mass_Media_160914%20.pdf

Gellner, E. (1990). Trust, cohesion, and the social order. In D. Gambetta (Ed.), Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations (pp. 142-157). Oxford, Cambridge: Basil Blackwell.

Glynn, C. J., & Huge, M. E. (2014). Speaking in spirals: An updated meta-analysis of the spiral of silence. In W. Donsbach, C. T. Salmon, & Y. Tsfati (Eds.), The spiral of silence: New perspectives on communication and public opinion (pp. 65-72). New York, London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Greenberg, B.S. (1966). Media Use and Believability: Some Multiple Correlates. Journalism Quarterly, 43 , 665-670. [ Links ]

Gronke, P., & Cook, T. E. (2007). Disdaining the media: The American public’s changing attitudes toward the news. Political Communication, 24 (3), 259-281.

Gunther, A. C. (1992). Biased press or biased public? Attitudes toward media coverage of social groups. Public Opinion Quarterly, 56 (2), 147-167. [ Links ]

Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L. & Black, W.C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis , Prentice-Hall International Inc., Englewood Cliffs, [ Links ] NJ.

Haller, M. (1992). Die Journalisten und der Ethikbedarf (Journalists and the Need for Ethics). In Medien-Ethik (Media Ethics), edited by Michael Haller and Helmut Holzhey, 196–211. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems. Three models of media and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hardt, H. (1990). Newsworkers, Technology, and Journalism History. Critical Studies in Mass Communication . 7 (4), 346–365. DOI: 10.1080/15295039009360184. ISSN 0739-3180.

Hoffner, C., & Rehkoff, R. A. (2011). Young voters' responses to the 2004 U.S. presidential election: Social identity, perceived media influence, and behavioral outcomes. Journal of Communication, 61 (4), 732-757. [ Links ]

Jackob, N.G.E. (2010). No Alternatives? The Relationship between Perceived Media Dependency, Use of Alternative Information Sources, and General Trust in Mass Media. International Journal of Communication, 4, 589-606. [ Links ]

Johnson, T. J., & Kaye, B. K. (1998). Cruising is believing? Comparing the Internet and traditional sources on media credibility measures. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 75 (2), 325-245. [ Links ]

Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2001). The elements of journalism: What news people should know and the public should expect. New York: Three Rivers Press. [ Links ]

Lauk, E., Harro-Loit, H. (2017). Journalistic Autonomy as a Professional Value and Element

of Journalism Culture: The European Perspective. International Journal of Communication 11(2016), 1956–1974.

Lee, T. T. (2005). The liberal media myth revisited: An examination of factors influencing media bias perception. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 49 (1), 43-64. [ Links ]

Lee, T. T. (2010). Why they don’t trust the media: An examination of factors predicting trust. American Behavioral Scientist, 54 (1), 8-21.

Luhmann, N. (1990). Familiarity, confidence, trust: Problems and alternatives. In D. Gambetta (Ed.), Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations (pp. 94-107). Oxford, Cambridge: Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Mierina, I. (2011). Political participation and development of political attitudes in post-communist countries. PhD Thesis, University of Latvia, Riga.

Ministry of the Interior (2016). National Security Audit. Retrieved from http://www.mvcr.cz/cthh/clanek/audit-narodni-bezpecnosti.aspx

Mishler, W., & Rose, R. (2005). What are the political consequences of trust? A test of cultural and institutional theories in Russia. Comparative Political Studies, 38 (9), 1050-1078. [ Links ]

Muller, J. (2013). Mechanisms of trust. News media in democratic and authoritarian regimes. Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag. [ Links ]

Newman, N, Fletcher, R., David A. L. Levy, D.A.L., & Nielsen, R.K. (2016). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2016. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Retrieved from http://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital-News-Report-2016.pdf.

Norris, P. (1999). Institutional explanations for political support. In P. Norris (Ed.), Critical citizens: Global support for democratic governance (pp. 217-235). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Pürer, H. (1992). Ethik in Journalismus und Massenkommunikation. Versuch einer Theorien-Synopse (Ethics in Journalism and Mass Communication).“ Publizistik , 37: 304–321.

Rose, R. (1994). Postcommunism and the problem of trust. Journal of Democracy, 5 (3): 18-30. [ Links ]

Singer, J. B. (2003). ""Who Are These Guys? The Online Challenge to the Notion of Journalistic Professionalism."" Journalism 4 (2): 139-163. [ Links ]

Smith, S. M., Fabrigar, L. R., & Norris, M. E. (2008). Reflecting on six decades of selective exposure research: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2 (1), 464-493. [ Links ]

Sullivan, L. E. (2009). Selective Exposure. In L.E. Sullivan (Ed.), The SAGE Glossary of the Social and Behavioral Sciences (p. 465). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Sztompka, P. (1992). Dilemmas of the great transition. Sisyphus, 2 (8), 9-28. [ Links ]

Sztompka, P. (2000). Trust: A sociological theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Tepljuk, V. M. (1989). The Soviet Union: Professional responsibility in mass media. In T.W. Cooper, C.G. Christians, F.F. Plude & R. A. White (Eds.), Communication ethics and global chang e (pp. 109-123). New York: Longman. [ Links ]

Tsfati, Y. (2003). Media scepticism and climate of opinion perception. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 15 (1), 65-82. [ Links ]

Tsfati, Y., & Ariely, G. (2014). Individual and Contextual Correlates of Trust in Media Across 44 Countries. Communication Research, 41 (6), 760-782. [ Links ]

Tsfati, Y., & Cappella, J. N. (2005). Why do people watch news they do not trust: Need for cognition as a moderator in the association between news media scepticism and exposure. Media Psychology, 7 (3), 251-272. [ Links ]

Tsfati, Y., & Cappella, J. N. (2003). Do people watch what they do not trust? Exploring the association between news media scepticism and exposure. Communication Research, 30 (5), 504-529. [ Links ]

Tsfati, Y., & Peri, Y. (2006). Mainstream media scepticism and exposure to extra-national and sectorial news media: The case of Israel. Mass Communication and Society, 9 (2), 165-187. [ Links ]

Westley, B., & Severin, W.J. (1964). Some Correlates of Media Credibility. Journalism Quarterly, 41, 325-335. [ Links ]

Witschge, T., & Nygren, G. (2009). “Journalism: A Profession Under Pressure?” Journal of Media Business Studies, 6 (1):37-59.