Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.13 no.3 Lisboa ago. 2019

https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS13320191439

Amateur subtitling in a dubbing country: The reception of Iranian audience

Masood Khoshsaligheh*, Saeed Ameri*, Binazir Khajepoor**, Farzaneh Shokoohmand*

*Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran

**Concordia University, Canada

ABSTRACT

Although dubbing is the official and dominant modality of translating foreign films and television series in Iran, amateur subtitling has been increasingly used by the Iranian audience for audiovisual products that are not dubbed, or at least not soon enough or not without substantial 'cultural appropriation.' Given the increasing attention paid to viewers' reception in the domain of audiovisual translation, this study attempts to explore the reception of Iranian viewers of the non-professional subtitling into Persian. Both qualitative and quantitative approaches were employed for the present research. Initially, the qualitative analysis of the focus groups conducted with consumers of such products suggested five main themes: translational, translatorial and technical expectations as well as the advantages and disadvantages. The quantitative analysis of the survey data confirmed the five themes in the second phase of the study.

Keywords: amateur subtitling, non-professional subtitling, reception, audience, audiovisual translation, Iran

Introduction

The production and circulation of audiovisual materials with the aim of entraining, informing or educating is an undeniable fact in many societies (Diaz-Cintas, 2015, p. 632). Thanks to advanced technologies, fans now create their subtitles for foreign products to allow audiences "to have immediate access to new episodes of popular series or new films" (Gambier, 2013, p. 53). This has become "an important source of entertainment for the general audience" (Orrego-Carmona, 2014, p. 52) especially in societies like Iran where not all foreign products have a chance to be officially dubbed and reach the general public (Khoshsaligheh & Ameri, 2016). The prosumers's turn (Tapscott & Williams, 2006) in terms of audiovisual translation (AVT)—where audiences or consumers have become active producers of translations—has been well acknowledged in recent audiovisual translation (AVT) literature (Antonini & Bucaria, 2015; Antonini, Cirillo, Rossato, & Torresi, 2017b; Pérez-González & Susam-Saraeva, 2012). Besides this, over the past few years, a growing body of literature around the topic of non-professional subtitling reception began to emerge (e.g. Di Giovanni, 2018; Orrego-Carmona, 2014, 2016; Orrego-Carmona & Richter, 2018) albeit with a European focus.

What has not yet been examined is the reception of subtitling in Iran where dubbing and voice-over have enjoyed a wide acceptance for solving language barrier for cinematic fiction and non-fiction products. Bearing this in mind, the investigation of general attitudes or opinions of the viewers, however, helps shed light on the audience's needs and expectations, hence, it can deepen our understanding of the issue at hand. Against this background, this investigation explores Iranian viewers' reception of amateur subtitling.

Theoretical framework

Non-professional subtitling

In defining a non-professional translator, Antonini, Cirillo, Rossato, and Torresi (2017a, pp. 6-8) numerate these features: not having specific training in translation, being bilingual (or knowing the language pairs for the translation), not being recruited for the work as it is done voluntarily, not being paid for the work, and finally not following any specific code of ethics or set of standards of practice. For them, the features are not always true and may vary in different situations. As far as the format of non-professional subtitling is concerned, it can be divided into 'pro-am (professional-amateur) subtitling' and 'innovative subtitling' (Orrego-Carmona, 2016). While the latter is more creative and includes more norm-breakings (e.g. font and color), the former tries to follow the professional norms of subtitling and produces subtitles with a near-professional quality (Orrego-Carmona, 2016).

Neither 'pro-am subtitling' nor 'innovative subtitling' does completely represent the Persian non-professional subtitling simply because it includes features from both types. For example, their translation quality is reportedly low (Khoshsaligheh & Fazeli Haghpanah, 2016) and they tend to ignore spatial and temporal requirements of professional subtitling (Ameri & Khoshsaligheh, forthcoming; Khoshsaligheh & Ameri, 2017b), not to mention the codes of professional AVT practice in Iran (Khoshsaligheh, Ameri, & Mehdizadkhani, 2018). According to Ameri and Khoshsaligheh (forthcoming), Iranian amateur subtitlers are not also aware of guidelines of subtitling such as character limitations per line or reading speed rates. Yet, they barely intervene with the original as the use of different colors and fonts is not common and subtitles do not appear on different parts of the screen. The use of commentaries is, however, quite common in these subtitles. Persian non-professional subtitling is currently very extensively present; at least one SubRip caption (SRT) version for most films or television series, released in the US or in the rest of Anglophone world, can be readily found online. Iranian fan translators offer translations with minimal delay. At times, a product is subtitled within a few days from the original release in the US without any censorship unlike the state-generated dubbed versions into Persian. Also, the pirated versions of foreign films and television series are easily accessible online for the Iranian users free of any charge or at a low cost (Ameri & Khoshsaligheh, forthcoming).

As mentioned above, features associated with non-professional subtitling definition do not always hold true with the Iranian phenomenon of subtitling by amateur subtitlers. In a recent qualitative Iranian study, Ameri and Khoshsaligheh (forthcoming) found that a number of these subtitlers have been educated in translation or languages, but there were several cases with an educational background in biology, computers and so forth. Although some have been trained in translation, they had no rigorous training in AVT because they were students of English literature and those who were a translation major did not receive any systematic training for subtitling. The other results of this qualitative research reveal that a group of these subtitlers work for the unauthorized websites sharing the pirated versions of the originals and they receive a small fee against the work they do. Therefore, this could be concluded, albeit with caution, that the Iranian amateur subtitling system is very complicated and it is difficult to reach a consensus to properly define it.

Reception studies

In the present study, the concept of reception, as Gambier (2018) argues, is understood as experiences, attitudes and opinions of users of translation, and these attitudes are investigated typically using questionnaires or interviews. Studies on professional subtitling reception have addressed different issues including the comparative reception of subtitling with dubbing or voice-over (Di Giovanni, 2012; Perego, Missier, & Bottiroli, 2015), the effectiveness of subtitling (Perego et al., 2016; Perego et al., 2015), the reception of culture specific references or humor (Bucaria, 2005; Fuentes Luque, 2003), and audience general attitudes and opinions (Alves Veiga, 2006; Di Giovanni, 2016; Szarkowska & Laskowska, 2015). All the reported studies were concerned with subtitles produced by professionals, based on the codes of professional subtitling practice. From 2015 onwards, two groups of empirical papers have been published; one group has addressed the reception of non-professional subtitling (e.g. Di Giovanni, 2018; Orrego-Carmona, 2014, 2016; Orrego-Carmona & Richter, 2018), while the other group has dealt with some of the features of non-professional subtitling which have been used in professional subtitles (e.g. Caffrey, 2009; Lång, Mäkisalo, Gowases, & Pietinen, 2013; Perego, Del Missier, Porta, & Mosconi, 2010).

In a project in Finland, Lång et al. (2013) empirically showed that badly synchronized subtitles do affect the gaze behavior of the viewers, but the viewers were not consciously aware of such a fault. As a matter of fact, they failed to notice most faulty subtitles. The results of other studies on manipulated subtitles suggested a similar idea. According to an experiment by Perego et al. (2010), ill-segmented subtitles—which is discouraged in the subtitling industry—were processed with no problem, indicating no significant impact on the subtitling viewing process. Another 'golden rule' which is recommended in the subtitling industry is that "a subtitle should not be maintained over a cut" as it would lead to re-reading of the same subtitles (Díaz Cintas & Remael, 2007, p. 91). The results of an eye-tracking study, however, challenged this issue as most viewers did not re-read subtitles maintained over a shot (Krejtz, Szarkowska, & Krejtz, 2013).

Caffrey (2009) examined the effects of a non-professional feature, 'the pop-up gloss'—a kind of commentary for explaining cultural elements or any other necessary information—, which has been adopted in some professional subtitling in the case of TV anime, on viewers' reception. The analysis of the data showed that the use of such a feature promotes viewers' understanding of culturally-marked items. However, the viewers spent less time on reading subtitles because more effort was required for processing a pop-up gloss in subtitles.

Künzli and Ehrensberger-Dow (2011) investigated the reception of 'innovative subtitling' where additional information was offered in the form of 'surtitles' at the top of the screen—this was similar to 'the pop-up gloss' in Caffrey's (2008) study. The findings revealed that the presence of the surtitles did not negatively influence the process of reception and the difference between the use of surtitles and subtitling in terms of reception capacity was not statistically significant. The participant also showed a neutral attitude towards the effectiveness of surtitles in clarifying the metalinguistic information.

Orrego-Carmona (2014) examined young audience's preferences and attitudes concerning non-professional subtitling in Spain. The reported findings showed that at least a large group watch subtitled products on a regular basis and they use subtitling to improve their foreign language listening skills and vocabulary treasury which is in consistent with the findings of Ameri and Ghodrati (2019) in the Iranian context. Delay in distributing the cinematic programs in their country received severe criticism from the participants as they would like to have access to the products much sooner. They therefore had to resort to non-professional subtitling since such versions were made available much sooner. Interestingly, the participants did not always tend to watch subtitled products as watching and reading subtitling is a demanding task and naturally it would not be the best choice when one needs to relax. Participants' partial command of English prompted them to compare the subtitles against the original to spot occasional mistakes, as reported by Orrego-Carmona (2014). Using eye-tracking, Orrego-Carmona (2016) showed that fansubbing is not negatively received by the audience and no significant difference was reported in terms of professional and non-professional subtitling viewing except that the former allowed a more stable reading behavior for the viewers. That's said, the author mentioned that he was examining "pro-am" [professional-amateur] subtitling. There have been two recent studies on non-professional subtitling reception by Orrego-Carmona and Richter (2018) and Di Giovanni (2018). The former is mainly concerned with the downloading rate of Original NETFLIX series subtitles on subtitling sharing websites, and the latter is an experiment with the intention of comparing subtitles made by professionals and those made by non-professionals in terms of comprehension and appreciation.

The purpose of this article is twofold. Initially, the research aims to identify what the Iranian viewers' attitudes and opinions were with regard to amateur subtitling in Iran. The second is to provide insight into their needs and expectations—needs, beliefs and expectations brought up through their exposure to amateur subtitling.

Method

Design

To explore the reception of Persian amateur subtitling by the Iranian audience and provide initial empirical insight into the fairly unknown aspects of this phenomenon, this inquiry consists of qualitative and quantitative stages. In the first phase, qualitative data were collected using focus group interviews, and in the next phase, quantitative data were gathered through a self-designed questionnaire instrument.

Participants

In the qualitative phase of the study, ten men and eight women at the age range of 22 to 46 (M=28) contributed to the study by participating in three focus group interviews. Using criterion sampling (Dörnyei, 2007), Iranian adult native speakers of Persian who were regular consumers of non-professional subtitling were identified and invited. The participants of the first group were recruited from Mashhad and the second and third groups from Tehran in Iran. All the participants were non-language majors.

In the quantitative phase, 483 men (n=261) and women (n=222) at the age range of 18 to 59 (M=29.7) completed the questionnaire. The participants were Iranian adult native speakers of Persian who were used to watching Persian subtitled programs, and they were from different parts of Iran. Due to practical limitations, their proficiency in English was not possible to be assessed and accordingly controlled. Nonetheless, all the participants were selected from among non-language majors.

Instrumentation

Initially, a focus group interview technique was used to gain qualitative insight into the reception of non-professional subtitling into Persian. Given the limited research on the topic, the qualitative data were also used to pool a list of relevant items for the questionnaire. In the next phase, an originally-designed questionnaire was employed to collect quantitative data on the Iranian viewers' expectations and needs of subtitling [1].

Procedures

The focus group interviews were conducted using a semi-structured protocol, which consisted of several leading questions informed by the literature. The interviews approximately took 55, 70 and 90 minutes. The interviews were audio-recorded and the transcription of the interviews facilitated the analysis. For the analysis of these qualitative data, 'thematic analysis' was used through which the data are analyzed to identify dominant and main themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

The Amateur Subtitling Reception Questionnaire (ASRQ), employed for the quantitative phase, comprised 35 items, which were selected from among over 50 items initially extracted from the qualitative data from the first phase of the study. To achieve the initial piloting of the scale (Dörnyei & Taguchi, 2010), the first draft of the 50 items were subjected to the comments and revision of several Iranian TS scholars. Based on their overall recommendations and opinions, 15 items were excluded and some items were rewritten and edited to improve their clarify and comprehensibility. To form the initial draft, the remaining 35 items were based on a rating scale of five options from 1 (strongly disapprove) to 5 (strongly approve). To achieve the final piloting (Dörnyei & Taguchi, 2010), the second version of the NSRQ was piloted on a small sample (n=15) of the target population. The comments and inquiries of the participants were used to edit the ASRQ. The final draft of the ASRQ, which was in Persian to match the participants' language, was used to collect the views of 483 participants. The ASRQ had seven sections; namely, the instructions, demographic information, translation expectations, technical expectations, translatorial expectations, subtitling advantages, and subtitling disadvantages. The items of the first groups were related to expectations and needs of Iranian viewers of subtitling and the last group addressed their general perceptions of subtitling advantages and disadvantages. This should be mentioned that the items within the questionnaires were randomized and the categorizations were made after the data collection for the data analysis.

After obtaining the questionnaires, the responses were analyzed statistically. To establish the construct validity of the survey results and verify the qualitatively obtained five categories of the items, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was run through structural equation modelling (SEM) on IBM SPSS AMOS 21.0. Using IBM SPSS 21.0, scale reliability analysis and descriptive statistics were analyzed and reported too.

Results

Qualitative Results: Focus Group Interviews

After collecting the data from the focus groups, they were thematically analyzed and five main themes emerged. The first three themes indicated translational, translatorial and technical expectations of the Iranian viewers while the last two categories represented themes regarding the advantages and disadvantages of Persian non-professional subtitling received by the participants. The second phase of the study also quantitatively confirmed the categorization of the five main themes. In the following, main notes from each of the categories are presented.

Theme I: Translational Expectations

Initially, some comments targeted the rendition of the humorous elements in films or television series. What can be inferred from the participants' statements was that the style of the product should be consistently transferred in the subtitled version. In that line, they criticized excessively free translation used in some subtitles in which additional humorous elements are added to the segments of the target version which originally did not contain any humorous element, and as such the style of the product is not respected. This case at times is observed in some amateur subtitles into Persian—usually on whimsical impulses of the translator, who adds elements to add or enhance the load of humor in the translation, most often by adding the local color and referencing allusions of Persian language and culture (Fazeli Haghpanah & Khoshsaligheh, 2018; Khoshsaligheh & Ameri, 2017b; Khoshsaligheh & Fazeli Haghpanah, 2016). In professional subtitling, "[t]he interference and presence of the translator through metatextual interventions […] in the form of footnotes or glosses" is very rare and is not recommended (Díaz Cintas & Remael, 2007, p. 141). Although the stark contrast between the visual and local cultural references would be found numerous to some, a number of participants did not tend to approve of that approach. A participant explained:

"I agree with Reza. We sometimes notice that some translations do not correspond with the scene; some may like this but I don't! You have probably watched The Lorax [Chris Renaud, 2012]. In a scene where Lorax is introducing himself as the guardian of the trees, in a parenthesis a strange note appears on the screen 'he looks like Famil-e Dour'!' [Famil-e Dour is the name of a puppet which is a popular character in an Iranian TV show.] That was really silly!"

As far as cultural elements are concerned, the participants did not favor those translation which replace the original cultural elements with those of Persian. They were interested in translations which highlight the otherness of the original. One of the participants believed that the use of such translations could challenge the natural reception of the subtitles because the visual is always a big reminder of a non-Persian view. Several participants preferred subtitles based on a foreignization strategy (Venuti, 1998) yet accompanied with parenthetical explanations and clarification of the culturally distant concepts. Although the use of parentheses may not be conveniently practical due to the time and space constrains in subtitles, some research has revealed that the use of pop-up glosses may positively affect the comprehension of the elements (Caffrey, 2009; Künzli & Ehrensberger-Dow, 2011). After all, the Iranian amateur subtitlers also make use of parenthetical additions and commentaries in their work (Ameri & Khoshsaligheh, forthcoming; Khoshsaligheh & Ameri, 2017b; Khoshsaligheh & Fazeli Haghpanah, 2016).

The participants believed that omission can be an acceptable strategy, when dealing with routine expressions like hello or ok or any simple phrase than can be understood through the visual or context. Even though this appears to be a recommended strategy in Europe (Karamitroglou, 1998), the effectiveness of such a strategy, however, depends on the foreign language involved since English or Arabic is by far better understood in Iran than Mandarin or Italian.

The rendition of idiolects of characters was brought up, and the interviewees mentioned that the peculiar speech habits of the characters should be maintained in subtitles even though this issue in professional subtitling depends on the function of the idiolect and its importance, and they certainly pose challenges in the translation (Díaz Cintas & Remael, 2007). They also favored full translation of songs especially if they were an important element in the creative development of the plot. Songs are typically translated or sometimes replaced by new songs in Persian fansubbed products, but amateur subtitlers' approach to the rendition of idiolects of characters varies, probably reliant on their competence and familiarity with the original culture. A participant clarified:

"I know some English but not that much to let me watch a film and fully understand it without subtitles. I remember watching The Terminal [Steven Spielberg, 2004] some years ago with Persian subtitles. The main character, Tom Hanks, had a special way of speaking in English. He had just arrived from a fictitious country to an American airport. Although I could hear that he spoke English in a very special way and with a foreign accent, the translation did not reflect that in anyway."

The opening credits and visually verbal signs in films and series were also discussed. Against the common practice in Persian amateur subtitling, it seemed that most participants dislike it when they are left untranslated. In this regard, one interviewee expressed:

"It is irritating that often the introductory or closing narratives, as well as the texts in the visual like the street signs or text messages are not translated in Persian subtitles. I recently watched a Chinese film, Under the Hawthorn Tree [Zhang Yimou, 2010], and a French one, I Stand Alone [Gaspar Noé, 1998]. I really liked it when the textual information within the films was also subtitled into Persian."

A sensitive topic was also discussed—taboo rendition in subtitling. As opposed to the dominant ideology in Iran, most of the participants took issue with the idea of mitigating or deleting the taboo items because of the damage to the creative spirit of the work of art. One of the participants offered a conservative solution as the first and last letter of the taboo especially swear expressions be written and the rest shown with three asterisks, which was dismissed by many others for its distracting nature. They argued the challenging nature of taboo translation in Persian subtitling in Iran, and how it contrasts taboo translation for the Anglophone cultures. What they were discussing has been theorized by Hall (1976) when proposed the continuum of high-context culture to low-context culture. The Iranian society differs from the Anglophone world (Hall & Hall, 1990) in that it is a much higher-context culture as the way messages are expressed is more significant than the how the message is worded and so much can be left unexpressed, relying on the immediate context.

There were also some few comments on mistakes and errors in the translation for the subtitles, and poor coherence and low naturalness of the target language in the amateur Persian subtitles were other common complaints. This is perhaps because such translations are barely edited, while in the professional subtitling industry, revision and proofreading are of necessity to deliver a good quality product (Díaz Cintas & Remael, 2007, p. 33). This highlights the fact that the participants probably demand a quality translation. One stated:

"Despite highest recommendations from many to watch this blockbuster, I had to stop watching The Wolf of Wall Street [Martin Scorsese, 2013] in the first thirty minutes. The Persian subtitle was awful as if translated by Google. There was no logical connection between dialogues and it was really difficult to make sense of what was happening on the screen."

Theme II: Technical Expectations

In terms of the technical issues of subtitling, the color of the subtitles was the first issue raised by the interviewees who asserted that the color should contrast against the visual background to facilitate reading which is pretty in line with common conventions of professional subtitling (Díaz Cintas & Remael, 2007, p. 130). It was suggested by the participants that subtitles should ideally be offered in several colors to choose. Although it is not possible when an SRT file is involved, many video players like VLC Media Player can help the users change the color of the subtitles in the case of closed subtitling.

Aside from the instructional or entertaining short videos with embedded subtitles with a fixed color largely found on Persian Telegram channels or Instagram pages, the subtitles for films and television series are available in an SRT format. Yet, it is not difficult subtitles with a Sub Station Alpha style where the viewer will have no control over the aesthetical features of the subtitles. One of the viewers commented on the importance of the color in subtitles:

"I remember a black-and-white themed scene in Schindler's List [Steven Spielberg, 1993], where a girl in a red dress passes by. Imagine if the subtitles were red, this would damage the director's emphasis on the red color, and reduce the effect intended. But the film had a white subtitle and I had no idea how to change it into another color like yellow or something."

There is no empirical evidence on the number of lines in Persian amateur subtitling, but according to the authors' observations, typically one- or two-line subtitles are generated because the amateur subtitlers actually work based on English SRT files, in which the codes of good subtitling in terms of one or two lines are usually followed. Nevertheless, one participant reported Persian subtitles with three or even four lines especially in those products with embedded subtitles. It should be noted that the problem with open subtitles is that, at times, they are not translated from an already-cued SRT file as no SRT file is available for them and the amateur subtitlers have to produce and spot/synchronize the subtitles. Several participants did not mind three-line subtitles per se provided that the lines were short and did not occupy too much space. From a professional perspective, subtitles with two lines are normally suggested in the industry (Díaz Cintas & Remael, 2007; Karamitroglou, 1998), but recent attitudinal research revealed that some viewers also favor three-line subtitles (Szarkowska & Laskowska, 2015, pp. 192-193). Nevertheless, experimental studies are needed to challenge this issue.

The timing of the subtitles on the screen—known as cuing in the industry—was also brought up. The participants believed that subtitles should not appear before the character started speaking but it should be either simultaneous or slightly delayed. Those in favor of delayed appearance justified that the mind could easily make the connections—a view supported by the professional codes of subtitling (Karamitroglou, 1998). One viewer commented:

"I follow several American TV series like Arrow [2012-present]. The Persian subtitle is available for download in less than a day or so. I appreciate the promptness, and I do not really care about the appearance of subtitles since it can be easily reformatted using KMPlayer. I can also play back a scene if the subtitle on the screen disappears too quickly which is not uncommon."

The comments of the interviewees revealed that cueing or spotting of some subtitles was not satisfactory at least to some. That could be due to two reasons: the Persian amateur subtitlers—due to their limited language competence and creative spirit, which is the typical of the untrained translators—tend to literally render almost everything in the original and does not respect spatial constraints. Also, considering that these subtitles are produced with rush often within a day from the release of the original, fansubbers can barely afford to pay attention to temporal and spatial constraints, even if familiar with such rules. An interviewee mentioned:

"I wonder why Persian subtitles are apparently longer than the typical English ones. I watch The Ellen DeGeneres Show [2003-present] with Persian subtitles. Sometimes I feel that the subtitles are too long that they cover almost the whole space of the bottom of the screen from the very right to the very left—too hard to read and watch at the same time."

In this comment, the respondent is probably referring to the font size of the subtitles which appears to be large to cover the whole lower part of the screen. The review of the responses pertaining to this theme revealed that the viewers were critical of the technical aspects as they seemed to have negatively influenced their flow and enjoyment of watching even though Díaz Cintas and Remael (2007, p. 80) comment that "parameters governing the technical dimension are less exposed to criticism than guidelines about subtitle layout". Iran has no subtitling tradition to serve as a yardstick or standard for the fansubbers to follow while the codes of good subtitling have long been put forward in the European context (Ivarsson & Carroll, 1998). This final result is not consistent with an eye-tracking study by Orrego-Carmona (2016) in which Spanish non-professional subtitling was not negatively received when compared with the professional subtitling, suggesting Persian fansubbing probably differs from its Spanish counterpart or the results should be compared with Persian experimental studies.

Theme III: Translatorial expectations

As for the Iranian context, there is little information available on the profile of Persian fansubbers, but according to the authors' observations and the study by Ameri and Khoshsaligheh (forthcoming), a great many of the Persian amateur subtitlers have no training in translation or even languages either. A local research, although limited in scope, also reveals their lack of formal training in translation (Khoshsaligheh & Fazeli Haghpanah, 2016) and we know that AVT training in Iran is of poor quality with insufficient professional trainers (Khoshsaligheh & Ameri, 2017a). In our focus-group discussions while participants were discussing errors and mistakes one said:

"This is Iran, a country where everybody dares to venture and try something for which they are clearly not prepared. Why on earth would a person who has only learnt English language at some levels attempt to do subtitling. Translating a film is obviously more than knowing some foreign language."

On the requited competence for such a task, some of the participants believed that translating a film is the same as translating a literature; at first, one should be familiar with the writer and his/her style and then begin the translation. This could be ascribed to the second level of competence—linguistic skills—advocated by Skuggevik (2009, p. 198). One asked:

"You guys watch Japanese anime, don't you? Do you think those who subtitle them know Japanese? Or they do that through the English version? I don't think they know Japanese."

For the participants of the study, relay translation by the non-professionals using a third language seemed to increase the potential for more mistakes i.e. the transfer of those mistakes already made in the pivotal text. However, some disagreed with dismissing this practice. One explained:

"Who's gonna translate Japanese anime in Iran from its original language? How many people know Japanese to complete a translation from an original charge-free? Nobody! So we have to welcome a translation based on an already translated text and accept the fact that it might have transferred several mistakes which are most probably repeated in the Persian version! If they weren't, we would never even know of the Japanese anime!"

In response to the comment of the previous participant, another participant mentioned that:

"I personally appreciate it that they are doing this for no financial award. But how about the Persian language? Such poorly done translations are harming the Persian language by popularizing unnatural structures which have no precedence in the Persian language and literature."

Although the participants appreciated the free service by the fansubbers, some were alarmed by the poor quality of their translation and the intrusive nature of the unnatural language in such film renditions, which can potentially jeopardize the Persian language with the abundance of unnatural collocations, borrowed grammatical structures inconsistent with the local language sentence syntax, etc. These participants believed the problem mostly lied in the amateur subtitlers' poor knowledge of Persian language, their mother tongue, which makes them ignorant of the right collocations and existing and appropriate equivalents expressions and lexical combinations.

Themes IV & V: Advantages and disadvantages

Different from the previous three aspects focusing on the expectations of the participants in terms of the Persian non-professional subtitling, the remaining opinions of the interviewees' reception of subtitling involved the pros and cons of subtitling vs. dubbing into Persian. In fact, there has always been a metaphorical war between these two major modalities to assume superiority. The debate is now partly cooled down and has recently been approached more empirically than speculatively. Such comparisons have been challenged by new empirical evidence supporting that subtitling, while effective, may not be necessarily cognitively demanding than dubbing (Perego et al., 2010; Perego et al., 2016; Perego et al., 2015). It is very difficult to say anything about Persian subtitling reception without testing it via controlled experimental data. Nevertheless, in the absence of such evidence, the review of the subtitling watching experiences of viewers and their personal reception of its advantages and disadvantages can provide some preliminary insights. Increasing the possibility of watching more foreign films and series was a popular opinion among the participants. One of them commented:

"Compared to several years ago, there has been a great availability to English-speaking films and series online which are just a click away. Considering that their subtitles are at our disposal and on occasions more than one version, I have been able to watch a lot more foreign films and series than before."

Many believed that unlike dubbing, subtitling allows the foreign viewers to feel the authentic and the professional side of the product—received through the actors with their own voices. Some complained about the censorship in official Persian dubbing. One criticizes:

"Why should I watch a 90-minute film in a 70-minute version when trying to enjoy the Persian dubbed version? Much manipulation in dubbed versions makes it hard to follow and enjoy. I realize what the reasons are but these do not convince me to pick dubbing over subtitling".

Another hotly-discussed issue in recent years has been subtitling potentials for language learning. Subtitling has shown to have positive effects on foreign language learning (see Gambier, Caimi, & Mariotti, 2015). Almost all the interviewees stressed on the positive role of subtitles in foreign language learning in their own experiences.

The disadvantages of subtitles were also indicated. The most important one was the distraction and the difficulty in following the text on the screen. Some mentioned that they always miss something when watching subtitled programs and are forced to play back the missed scene. Although research has it reading subtitles is effortless, here we are dealing with amateur subtitles. According to Ameri and Khoshsaligheh (forthcoming), Persian fansubbers use more characters in their subtitles and are not committed to reductive approaches to subtitling which could make reading more demanding. Persian fansubbers tend to follow a literal approach in their translations and translate almost everything said by the actors. This way increases the amount of information presented in a given time and increases the subtitling reading speed as noted by Gambier (2013, p. 54) when discussing fansubbing.

Quantitative results: Survey Questionnaire

Validity and reliability

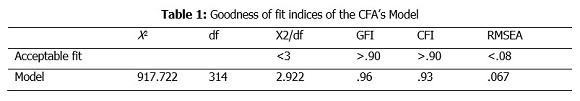

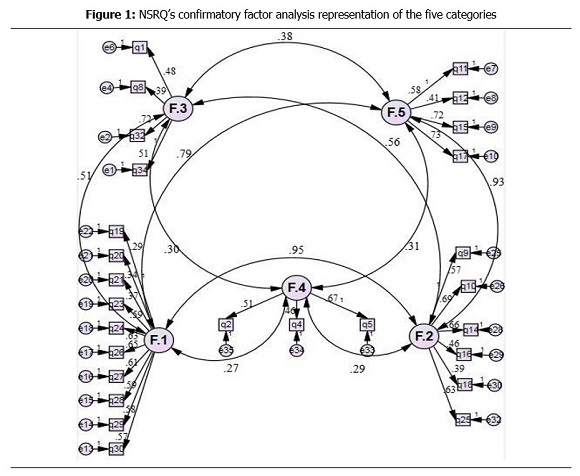

To examine the validity of the questionnaire data, using CFA, the association between each sub-factor of the achieved model was analyzed. Among 35 items, eight items which had low loading factor or were not significant, were excluded. To check the model fit, goodness of fit indices were used. For the present investigation, χ2/df, GFI, CFI, and RMSEA were employed. To assess the model fit, a number of fit indices were examined, including the chi-square magnitude which should not be significant, the chi-square/df ratio which should be lower than 2 or 3, the comparative fit index (CFI), the good fit index (GFI) with the cut value greater than .90, and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of about .06 or .07 (Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow, & King, 2006). As evident in Table 1, all the fit indices, RMSEA (.067), CFI (.93), GFI (.96) and the chi-square/df ratio (2.922), lie within the acceptable fit thresholds (Kaplan, 2009; Schreiber et al., 2006). The proposed model, therefore, had an adequate fit with the data collected for the survey. The final model can be seen in Figure 1. Additionally, to examine the reliability of the ASRQ, Cronbach's alpha was calculated.

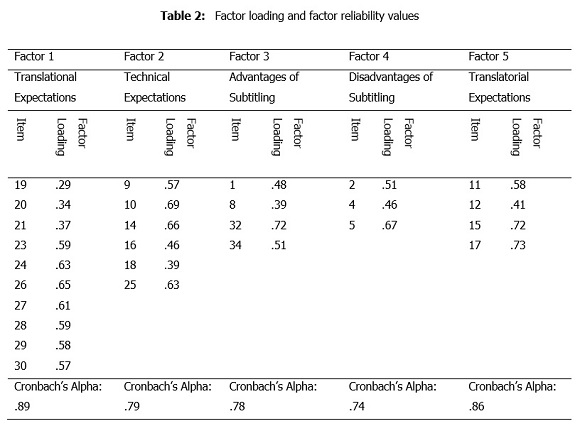

The reliability coefficient was 0.89 for Translational Expectations, 0.79 for Technical Expectations, 0.78 for Advantages of Subtitling, 0.74 for Disadvantages of Subtitling, 0.86 for Translatorial Expectations, and for total ASRQ was 0.82, which shows the scale enjoys acceptable internal consistency reliability (Table 2).

Reception of themes and the related items

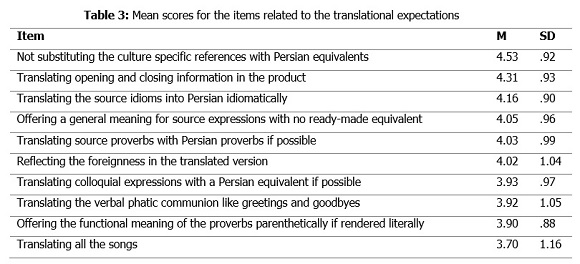

After the validity and reliability of ASRQ were confirmed, the overall perception of 483 participants of each of the five categories of ASRQ is examined by reviewing the achieved mean scores. The following tables (3-7) show the mean rating and standard deviation for each item related to every category based on the rating scale used in the questionnaire, ranging from strongly disapprove (1) to strongly approve (5). Given the structure of the instrument, as far as the norms were concerned, the higher the mean score, the more generally the item was approved, and in terms of the expectations, the higher the mean score, the more important the item was.

Translational expectations

The category of 'translational expectations' included ten items in the questionnaire with regard to the translation issues in non-professional subtitling into Persian. As Table 3 shows, almost all the related items received an approval rate or a very close one, suggesting that the participants preferred the otherness of the foreign content to be retained in the subtitles or in words of Venuti (1998), a foreignizing translation was preferred.

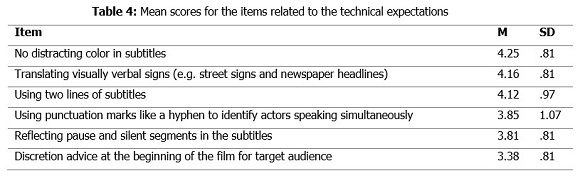

Technical expectations

The category of 'technical expectations' included six items with regard to the format and technical issues in non-professional subtitling. As evident in Table 4, most of the expectations also received an approval rate or a close one.

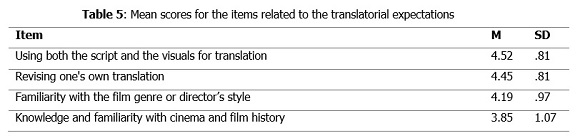

Translatorial expectations

The category of 'translatorial expectations' contained four items concerning the issues related to translator's or subtitler's duties and competence. As Table 5 shows, it is important for the viewers that the translators use both the script and the visuals during translation and review and edit their final work.

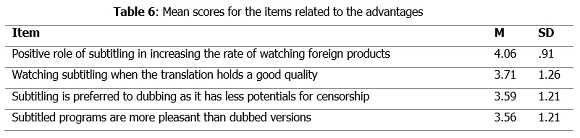

Advantages

The category of 'advantages' had four items about benefits of subtitling. As can be seen in Table 5, the participating viewers seemed generally to hold a neutral attitude towards the advantages of subtitling. The viewers agreed that subtitling plays a significant role in increasing the rate of watching foreign films. Regardless of poor quality translation of Persian subtitles (Khoshsaligheh & Ameri, 2017b; Khoshsaligheh & Fazeli Haghpanah, 2016) they would still watch the subtitled programs. The reason seems clear because they are forced to watch fansubbed products as they do not have any other alternatives because Iran tends not to dub many western films or series for the public, or at least in full, mainly due to ideological reasons (Khoshsaligheh & Ameri, 2016). It appears that the constant exposure of the viewers to such less-than-perfect subtitles has made them overlook the quality, and accept this norm.

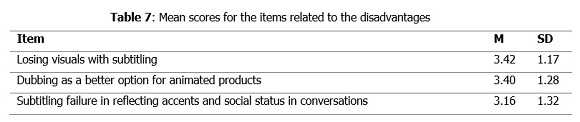

Disadvantages

The category of 'disadvantages' contained three items and as shown in Table 7, the participating viewers similarly revealed an almost neutral attitude towards the disadvantages of subtitling. That is, neither did they clearly approve nor disapprove of the items.

Discussion and conclusion

The present paper aimed to explore the reception of amateur subtitling among Iranian viewers. Drawing on the qualitative data from the first phase of the study, there were indications to noticeable changes in the AVT habits of the Iranian viewers who come from a country where dubbing is exclusively used for fiction content on state-run television networks or elsewhere. While Iran has never shown any inclinations towards subtitling (Ameri & Khoshsaligheh, 2018; Ameri, Khoshsaligheh, & Khazaee Farid, 2018), the Iranian viewers, however, seem to be willing to get out of their comfort zone and watch subtitled programs which they would not have access to otherwise, in full, soon enough or at all. This is consistent with the findings of other recent studies where the audience' viewing habits in dubbing countries have shifted towards subtitling (Orrego-Carmona, 2014; Perego et al., 2016). Although the study does not claim generalizable findings, trace of an AVT turn (Chaume, 2013) is prudently noticeable, as Ameri and Ghodrati (2019) have found some evidence.

The qualitative findings also showed that viewers' have some expectations in terms of the subtitles they choose to watch. In other words, they care about the subtitles they use to watch their favorite programs. Some of these expectations are quite in line with those professional practices devised for the industry. For example, the use of humorous elements in subtitles, while the style of the original program does not require them, is definitely forbidden in professional subtitling—as they "have a right to a qualitatively high-standard translation that will fill in the foreign language gaps for them" (Díaz Cintas & Remael, 2007, p. 146), and the Iranian audiences seek and approve of a translation which respects the original style of the program. The quantitative analysis of the data also give support to this claim that the audience would prefer a faithful translation or in translation studies terms, a foreignizing approach where the otherness of the program is respected. Although faithfulness is also stressed in professional subtitling, translations made for subtitling cannot reflect a full reproduction of the original program due to spatial and temporal constraints leading to reductions in translation. This might suggest that what translation scholars accept as good translation does not necessarily match what the audiences consider good or acceptable (Lång et al., 2013, p. 84). Nevertheless, erroneous subtitles, as Doherty and Kruger (2018) argue, "are likely to lead to increased cognitive load as the viewer must overcome the error in order to comprehend and integrate the presented information" (p. 189). That is the reason why some viewers reported errors and mistakes in Persian fansubbed versions. This should, however, be mentioned that we do not assume that viewers need to know English or the source language of the product to assess the subtitles as they use subtitles because they do not know the source language or have a limited knowledge of it, but some may react to mistranslations or unfaithful translations, as discussed above. Besides these, the respondents also raised their expectations about some subtitling mechanisms. For example, in addition to the appropriate color for displaying subtitles, they also favored two-liners over three- or four-liners and demanded the translation of visually verbal signs. All these have been well-mentioned in professional subtitling guidelines (e.g. Díaz Cintas & Remael, 2007; Karamitroglou, 1998).

The comments made by the viewers about subtitling advantages and disadvantages showed that the former outnumber the latter even though the general attitudes were neutral in the quantitative stage. Persian non-professional subtitling, as respondents argued, has given access to a wide variety of foreign content and this has increased the rate of watching foreign content in Iran, which in turn can play a pivotal role in foreign language learning. When it comes to disadvantages, subtitling was considered a cognitively demanding task and at times, but not always, viewers miss some information so they need to replay a scene. At the same time, they believed that subtitling is more enjoyable than dubbing as it maintains the authenticity and the true feel of the original. On another note, recent studies on professional subtitling report that watching subtitling is not necessary cognitively demanding but effective (Perego et al., 2010; Perego et al., 2016; Perego et al., 2015), and subtitles can offer a more immersive experience of the original program (Kruger, Sanfel, Doherty, & Ibrahim, 2016) and can be a beneficial tool for language learning (Ameri & Ghodrati, 2019; McLoughlin & Lertola, 2014). Given the limitations of the present study, it does not afford to challenge these findings from the European context, but the present research from Iran suggests that this modality might be received and processed differently in various situations and experimental research on Persian fansubbing is of necessity.

The second part of the study quantitatively confirmed the generalizability of the categorization achieved through the qualitative data in the first phase. This phase also quantitatively examined the viewers' general perception on the pros and cons of subtitling as well as their expectations in the aforementioned areas. The quantitative analysis in this study can assume significance in that it applies CFA through SEM to confirm the validity of the results, a procedure which, to the best of our knowledge, has been barely used in published literature in AVT studies. What is inferred from the survey findings is that that all items of the survey received positive or neutral attitudes from the participants. The results also revealed that the viewers favored translation wherein the otherness and peculiarity of the foreign content are maintained. To borrow translation studies terms (Venuti, 1998), they are more interested in foreignizing translation. Additionally, the subtitling advantages and especially disadvantages were received neutrally. The neutrality of perception of these items suggested that such statements might vary from a situation to another and might be difficult for the viewers to give a flat answer. This, therefore, highlights the need for experimental studies. Nevertheless, it was unanimously agreed by the participants that subtitling—even in in its non-professional form—has increased the rate of foreign film viewing among the Iranian. This is according to the viewers, and there is no official report or any research to substantiate this claim.

An important issue which requires some attention here is that subtitling fictional programs is not a standard practice in Iran; therefore, people have only access to dubbing and amateur subtitling. Given that Iranians are not used to subtitles and, as such, it is almost difficult for them to distinguish between professional and amateur subtitling, it is unlikely that participants can make this difference when they are talking about norms because their context has not allowed them to develop a baseline to assess professional subtitling. Consequently, the nature of this study differs from that of those studies originated from countries where subtitling is a standard practice. This issue, nevertheless, demands more research with an experimental design. Nonetheless, this should be pointed out that some research has shown that viewers used to professional subtitles cannot differentiate between professionals and non-professional ones (see Orrego-Carmona, 2016).

The aim of this study was not to assess the quality of subtitles according to the viewers but to gain insights into how people react to such subtitles and if they have any difficulty with them. The qualitative side of the article mirrored the general opinions of the users concerning subtitling and they mainly indicated to issues which negatively affected their comprehension and natural flow of watching a subtitled program.

The empirical findings of the paper delivered a series of new insights into such non-professional subtitling in Iran and supported the timely necessity of officially establishing subtitling as a supplementary modality alongside dubbing in Iran. Given the limitations of the present study, further research is recommended to benefit from larger and probability samples. In addition, other research designs like experiments (e.g. Abdi & Khoshsaligheh, 2018) or the use of cognitive research tools such as eye trackers (e.g. Zahedi & Khoshsaligheh, forthcoming) could yield valuable and more illuminating findings on Persian amateur subtitling reception and consumption.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Ferdowsi University of Mashhad under Grant 40668.

References

Abdi, Z., & Khoshsaligheh, M. (2018). Applying multimodal transcription to Persian subtitling. Studies About Languages, 32, 21-38. [ Links ]

Alves Veiga, M. J. (2006). Subtitling reading practices. In A. Assis Rosa & T. Seruya (Eds.), Translation studies at the interface of disciplines (pp. 161–168). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Ameri, S., & Ghodrati, M. (2019). جایگاه محصولات سینمایی خارجی در یادگیری زبان انگلیسی خارج از کلاس درس [Watching foreign audiovisual programs and out-of-class language learning]. Journal of Language and Translation Studies, 52(1), 75-105.

Ameri, S., & Khoshsaligheh, M. (2018). Exploring the attitudes and expectations of Iranian audiences in terms of professional dubbing into persian. Hermes, 57, 175-193. [ Links ]

Ameri, S., & Khoshsaligheh, M. (forthcoming). Iranian non-professional subtitling apparatus: A qualitative investigation. Mutatis Mutandis: Revista Latinoamericana de Traducción, 12(2). [ Links ]

Ameri, S., Khoshsaligheh, M., & Khazaee Farid, A. (2018). The reception of Persian dubbing: A survey on preferences and perception of quality standards in Iran. Perspectives: Studies in Translation Theory and Practice, 26(3), 435-451. doi: 10.1080/0907676X.2017.1359323 [ Links ]

Antonini, R., & Bucaria, C. (Eds.). (2015). Non-professional interpreting and translation in the media. Wien, Austria: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Antonini, R., Cirillo, L., Rossato, L., & Torresi, I. (2017a). Introducing NPIT studies. In R. Antonini, L. Cirillo, L. Rossato, & I. Torresi (Eds.), Non-professional interpreting and translation: State of the art and future of an emerging field of research (pp. 2 – 26). Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Antonini, R., Cirillo, L., Rossato, L., & Torresi, I. (Eds.). (2017b). Non-professional Interpreting and Translation: State of the art and future of an emerging field of research. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Bucaria, C. (2005). The perception of humour in dubbing vs. subtitling: The case of Six Feet Under. ESP Across Cultures, 2, 34-46. [ Links ]

Caffrey, C. (2009). Relevant abuse? Investigating the effects of an abusive subtitling procedure on the perception of TV anime using eye tracker and questionnaire. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), Dublin City University, Dublin, [ Links ] Ireland.

Chaume, F. (2013). The turn of audiovisual translation: New audiences and new technologies. Translation Spaces, 2(1), 105-123. doi: 10.1075/ts.2.06cha [ Links ]

Di Giovanni, E. (2012). Italians and television: A comparative study of the reception of subtitling and voice-over. In S. Bruti & E. Di Giovanni (Eds.), Audiovisual translation across Europe: An ever-changing landscape (pp. 171-190). Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Di Giovanni, E. (2016). Reception studies in audiovisual translation research: The case of subtitling at film festivals. trans-kom, 9(1), 58-78. [ Links ]

Di Giovanni, E. (2018). The reception of professional and non professional subtitles: Agency, awareness and change. Cultus Journal, 11, 18-37. [ Links ]

Diaz-Cintas, J. (2015). Technological strides in subtitling. In C. Sin-wai (Ed.), The routledge encyclopedia of translation technology (pp. 632-643). Abingdon, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Díaz Cintas, J., & Remael, A. (2007). Audiovisual translation: Subtitling. Abingdon, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Doherty, S., & Kruger, J.-L. (2018). Assessing quality in humanand machine-generated subtitles and captions. In J. Moorkens, S. Castilho, F. Gaspari, & S. Doherty (Eds.), Translation quality assessment: From principles to practice (pp. 179-197). London: Springer. [ Links ]

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Dörnyei, Z., & Taguchi, T. (2010). Questionnaires in second language research construction, administration, and processing (2nd ed.). Abingdon, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Fazeli Haghpanah, E., & Khoshsaligheh, M. (2018). انگیزهها و دلایل طرفدارزیرنویسی فیلمها و سریالهای کرهای [Fansubbers' motivations and reasons for subtitling Korean films and TV series]. . Language and Translation Studies, 51(3), 1-18.

Fuentes Luque, A. (2003). An empirical approach to the reception of AV translated humour: A case study of the Marx Brothers' 'Duck Soup'. The Translator, 9(2), 293-306. doi: 10.1080/13556509.2003.10799158 [ Links ]

Gambier, Y. (2013). The Position of Audiovisual Translation Studies. In C. Millán & F. Bartrina (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation studies (pp. 45-59). Abingdon, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gambier, Y. (2018). Translation studies, audiovisual translation and reception. In E. D. Giovanni & Y. Gambier (Eds.), Reception studies and audiovisual translation (pp. 43-66). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Gambier, Y., Caimi, A., & Mariotti, C. (Eds.). (2015). Subtitles and language learning: Principles, strategies and practical experiences. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Hall, E. (1976). Beyond culture. Garden City, NY Anchor.

Hall, E., & Hall, M. R. (1990). Understanding cultural differences: German, French and Americans. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural.

Ivarsson, J., & Carroll, M. (1998). Subtitling. Simrishamn, Sweden: TransEdit. [ Links ]

Kaplan, D. (2009). Structural equation modeling: Foundations and extensions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Karamitroglou, F. (1998). A proposed set of subtitling standards in Europe. Translation Journal, 2(2). [ Links ]

Khoshsaligheh, M., & Ameri, S. (2016). Ideological considerations and practice in official dubbing in Iran. Altre modernità, 15(Special Issue), 232-250. doi: 10.13130/2035-7680/6864 [ Links ]

Khoshsaligheh, M., & Ameri, S. (2017a). Didactics of audiovisual translation in Iran so far: Prospects and solutions. [ Links ] Paper presented at the National Conference on Interdisciplinary Approaches to Translation Education, Tehran, Iran.

Khoshsaligheh, M., & Ameri, S. (2017b). عاملیت مترجم و ویژگیهای ترجمه غیرحرفهای بازیهای ویدئویی (موردپژوهی آنچارتد 4: فرجام یک دزد) [Translator's agency and features of non-professional translation of video games (A case study of Uncharted 4: A Thief's End)]. Language Related Research, 8(5), 181-204.

Khoshsaligheh, M., Ameri, S., & Mehdizadkhani, M. (2018). A socio-cultural study of taboo rendition in Persian fansubbing: An issue of resistance. Language and Intercultural Communication, 18(6), 663-680. doi: 10.1080/14708477.2017.1377211 [ Links ]

Khoshsaligheh, M., & Fazeli Haghpanah, E. (2016). فرایند و ویژگیهای زیرنویس غیرحرفهای در ایران [The process and features of fansubtitling in Iran]. Language and Translation Studies, 49(2), 67-95.

Krejtz, I., Szarkowska, A., & Krejtz, K. (2013). The effects of shot changes on eye movements in subtitling. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 6(5), 1-12. doi: 10.16910/jemr.6.5.3 [ Links ]

Kruger, J.-L., Sanfel, M. T. S., Doherty, S., & Ibrahim, R. (2016). Towards a cognitive audiovisual translatology: Subtitles and embodied cognition. In R. M. Martín (Ed.), Reembedding translation process research (pp. 171-193). Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins [ Links ]

Künzli, A., & Ehrensberger-Dow, M. (2011). Innovative subtitling: A reception study. In C. Alvstad, A. Hild, & E. Tiselius (Eds.), Methods and strategies of process research: Integrative approaches in translation studies (pp. 187-200). Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Lång, J., Mäkisalo, J., Gowases, T., & Pietinen, S. (2013). Using eye tracking to study the effect of badly synchronized subtitles on the gaze paths of television viewers. New Voices in Translation Studies, 10, 72-86. [ Links ]

McLoughlin, L. I., & Lertola, J. (2014). Audiovisual translation in second language acquisition. Integrating subtitling in the foreign-language curriculum. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 8(1), 70-83. doi: 10.1080/1750399X.2014.908558 [ Links ]

Orrego-Carmona, D. (2014). Subtitling, video consumption and viewers: The impact of the young audience. Translation Spaces, 3, 51-70. doi: 10.1075/ts.3.03orr [ Links ]

Orrego-Carmona, D. (2016). A reception study on non-professional subtitling: Do audiences notice any difference? Across Languages and Cultures, 17(2), 163–181. doi: 10.1556/084.2016.17.2.2 [ Links ]

Orrego-Carmona, D., & Richter, S. (2018). Tracking the distribution of non-professional subtitles to study new audiences. Observatorio, 12(4), 64-68. [ Links ]

Perego, E., Del Missier, F., Porta, M., & Mosconi, M. (2010). The cognitive effectiveness of subtitle processing. Media Psychology, 13(3), 243-272. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2010.502873 [ Links ]

Perego, E., Laskowska, M., Matamala, A., Remael, A., Robert, I. S., Szarkowska, A., . . . Bottiroli, S. (2016). Is subtitling equally effective everywhere? A first cross-national study on the reception of interlingually subtitled messages. Across Languages and Cultures, 16(2), 205-229. doi: 10.1556/084.2016.17.2.4 [ Links ]

Perego, E., Missier, F. D., & Bottiroli, S. (2015). Dubbing versus subtitling in young and older adults: Cognitive and evaluative aspects. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 23(1), 1-21. doi: 10.1080/0907676X.2014.912343 [ Links ]

Pérez-González, L., & Susam-Saraeva, Ş. (2012). Non-professionals translating and interpreting: Participatory and engaged perspectives. The Translator, 18(2), 149-165. doi: 10.1080/13556509.2012.10799506 [ Links ]

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323-338. doi: 10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338 [ Links ]

Skuggevik, E. (2009). Teaching screen translation: The role of pragmatics in subtitling. In J. Díaz Cintas & G. Anderman (Eds.), Audiovisual translation: Language transfer on screen (pp. 197-213). London: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Szarkowska, A., & Laskowska, M. (2015). Poland – a voice-over country no more? A report on an online survey on subtitling preferences among Polish hearing and hearing-impaired viewers. In Ł. Bogucki & M. Deckert (Eds.), Accessing audiovisual translation (pp. 179-197). Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Tapscott, D., & Williams, A. D. (2006). Wikinomics: How mass collaboration changes everything. New York, NY: Portfolio.

Venuti, L. (1998). The scandals of translation: Towards an ethics of difference. London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Zahedi, S., & Khoshsaligheh, M. (forthcoming). مقایسه حرکات چشمی در خوانش واژگان قاموسی و دستوری زیرنویسهای فارسی با استفاده از فناوری ردیاب چشمی [Eye Tracking Function and Content Words in Persian Subtitles]. Language Related Research, 10(4).

Filmography

Noé, G. (Director). (1998). I Stand Alone [Motion picture]. France: Canal+, Les Cinémas de la Zone, Love Streams Productions and Procirep.

Renaud, C. (Director). (2012). The Lorax [Motion picture]. The United States: Universal Pictures and Illumination Entertainment.

Scorsese, M. (Director). (1998). The Wolf of Wall Street [Motion picture]. The United States: Red Granite Pictures, Appian Way Productions, Sikelia Productions and EMJAG Productions.

Spielberg, S. (Director). (1993). Schindler's List [Motion picture]. The United States: Amblin Entertainment.

Spielberg, S. (Director). (2004). The Terminal [Motion picture]. The United States: Amblin Entertainment.

Yimou, Z. (Director). (2010). Under the Hawthorn Tree [Motion picture]. China: Beijing New Picture Film.

Submitted: 6th December 2018

Accepted: 23rd April 2019

How to quote this article:

Khoshsaligheh, M., Ameri, S., Khajepoor, B. & Shokoohmand, F. (2019). Amateur subtitling in a dubbing country: The reception of Iranian audience. Observatorio, 13(3), 71-94.

Notes

[1] It should be mentioned that we did not use the phrase 'non-professional subtitling' in the interviews and questionnaires because the adjective 'non-professional' might affect the participating viewers' attitudes. Instead, we employed 'internet subtitling' as a general term.

[2] http://www.ef.com/ir/epi/ (Last accessed 22 February 2019)